Methionine Supplementation Benefits Lipogenesis in Goat Intramuscular Adipocytes, Likely by Inhibiting the Expression of SLC5A5

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Goat Intramuscular Preadipocytes

2.2. Cell Culture and Differentiation

2.3. Triglyceride Assay

2.4. Oil Red O Staining

2.5. Bodipy Staining

2.6. Crystal Violet Staining

2.7. EdU Proliferation Assay

2.8. Plasmid Construction, siRNA Synthesis, and Transfection

- siRNA-NC:sense 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′;antisense 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′.

- siRNA-SLC5A5-345:sense 5′-GCACCUACGAGUACCUGGA-3′;antisense 5′-UCCAGGUACUCGUAGGUGC-3′.

2.9. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.10. RNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.11. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Supplementation with Met on Cell Proliferation of Intramuscular Preadipocytes

3.2. Impact of Supplementation with Met on Cell Differentiation and Lipid Metabolism of Intramuscular Preadipocytes

3.3. Impact of Supplementation with Met on Survival Rate of Intramuscular Preadipocytes

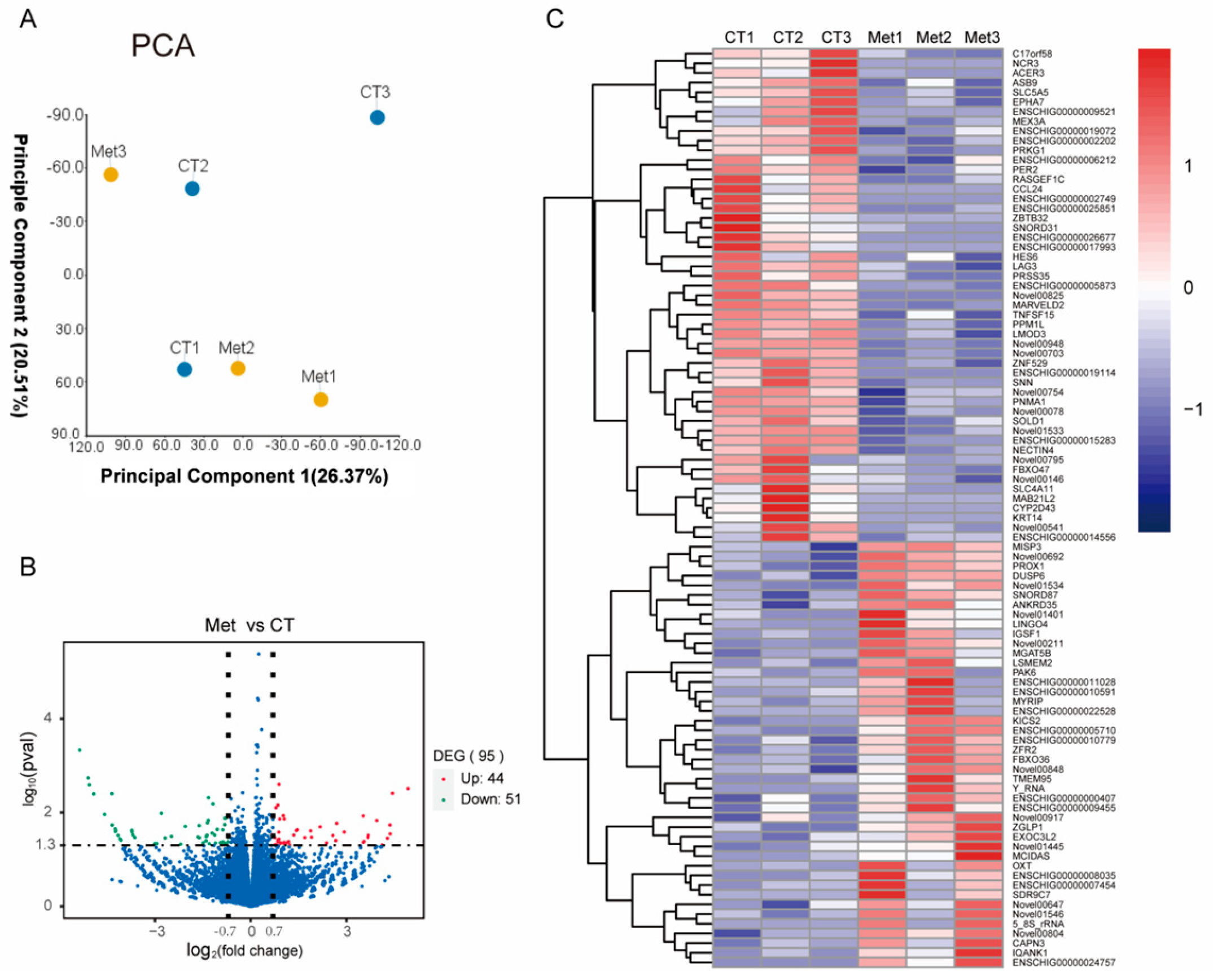

3.4. RNA-Seq Analysis

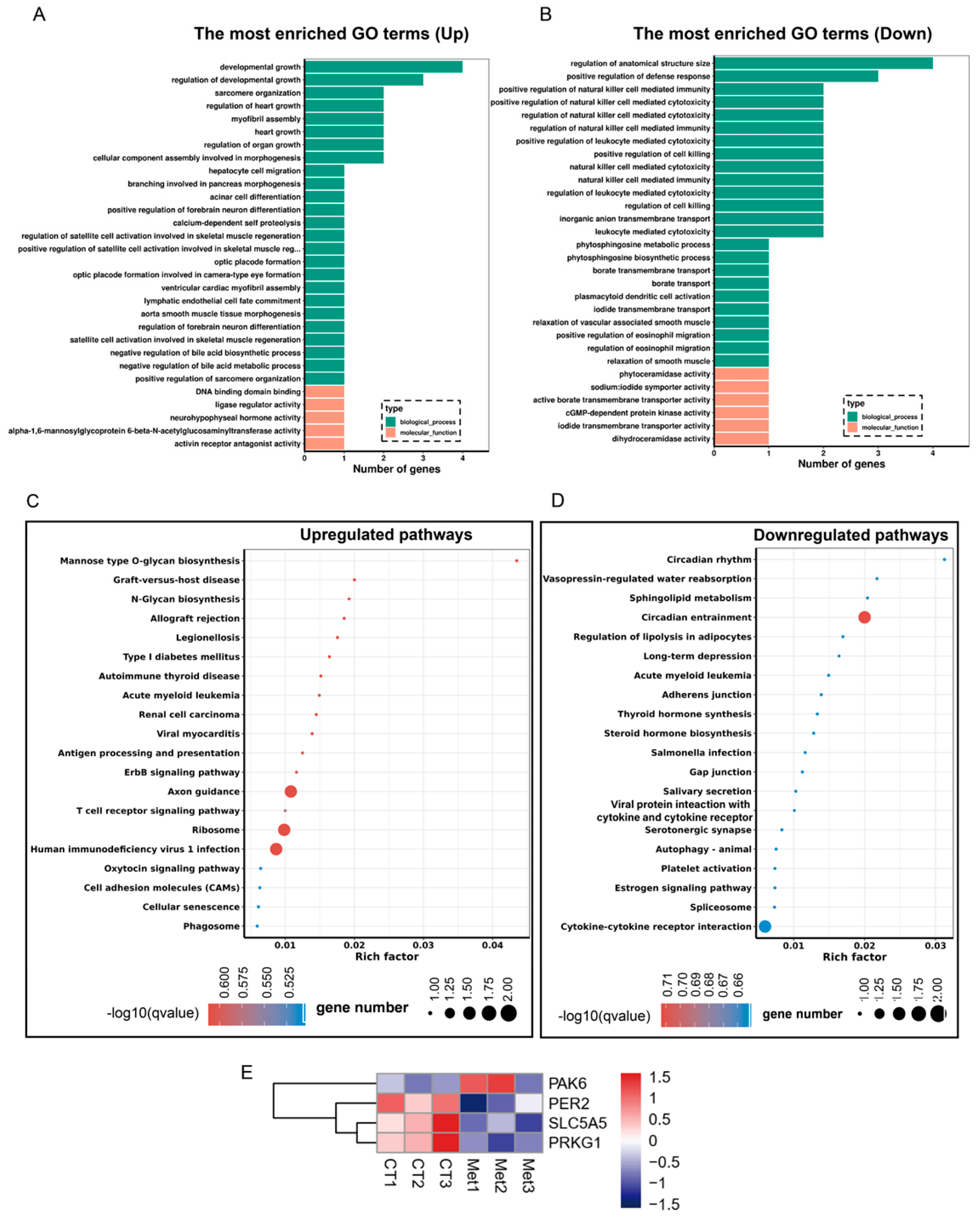

3.5. Enrichment Analysis of the Differentially Expressed Genes

3.6. Met Supplementation Influence on the Pathways Associated with Adipogenesis

3.7. Effect of Met Supplementation Following SLC5A5 Silencing on Goat Intramuscular Adipocyte Differentiation

3.8. The Effect of Met Supplementation on the Differentiation of Goat Intramuscular Adipocytes Following SLC5A5 Overexpression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Realini, C.; Pavan, E.; Johnson, P.; Font-I-Furnols, M.; Jacob, N.; Agnew, M.; Craigie, C.; Moon, C. Consumer liking of M. longissimus lumborum from New Zealand pasture-finished lamb is influenced by intramuscular fat. Meat Sci. 2021, 173, 108380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motoyama, M.; Sasaki, K.; Watanabe, A. Wagyu and the factors contributing to its beef quality: A Japanese industry overview. Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Zhu, M.J.; Underwood, K.R.; Hess, B.W.; Ford, S.P.; Du, M. AMP-activated protein kinase and adipogenesis in sheep fetal skeletal muscle and 3T3-L1 cells. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, E.D.; MacDougald, O.A. Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, X.; Yang, G.; Du, M. Review: Enhancing intramuscular fat development via targeting fibro-adipogenic progenitor cells in meat animals. Animal 2020, 14, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambele, M.A.; Dhanraj, P.; Giles, R.; Pepper, M.S. Adipogenesis: A complex interplay of multiple molecular determinants and pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, X.; Tang, Q.-Q. Transcriptional regulation of adipocyte differentiation: A central role for CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) β. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ma, Y.; Luo, Y.; Tang, G.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ye, B.; Huang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Du, M.; et al. Neonatal vitamin A administration increases intramuscular fat by promoting angiogenesis and preadipocyte formation. Meat Sci. 2022, 191, 108847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougald, O.A.; Lane, M.D. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression during adipocyte differentiation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64, 345–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbens, F.; Jansen, A.; van Erp, A.J.; Harders, F.; Meuwissen, T.H.; Rettenberger, G.; Veerkamp, J.H.; te Pas, M.F. The adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein locus: Characterization and association with intramuscular fat content in pigs. Mamm. Genome 1998, 9, 1022–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barendse, W.; Bunch, R.J.; Thomas, M.B.; Harrison, B.E. A splice site single nucleotide polymorphism of the fatty acid binding protein 4 gene appears to be associated with intramuscular fat deposition in longissimus muscle in Australian cattle. Anim. Genet. 2009, 40, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarese, V.; Bernlohr, D.A. Purification of murine adipocyte lipid-binding protein. Characterization as a fatty acid- and retinoic acid-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 14544–14551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotani, K.; Peroni, O.D.; Minokoshi, Y.; Boss, O.; Kahn, B.B. GLUT4 glucose transporter deficiency increases hepatic lipid production and peripheral lipid utilization. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 1666–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerk, I.K.; Wechselberger, L.; Oberer, M. Adipose triglyceride lipase regulation: An overview. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2018, 19, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.L.; Wang, B.; Deavila, J.M.; Busboom, J.R.; Maquivar, M.; Parish, S.M.; McCann, B.; Nelson, M.L.; Du, M. Vitamin A administration at birth promotes calf growth and intramuscular fat development in Angus beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, D.; Huang, H.; Zhang, M.; Sun, L.; Su, L.; Zhao, L.; Guo, Y.; Jin, Y. Probiotics increase intramuscular fat and improve the composition of fatty acids in Sunit Sheep through the adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2023, 43, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-Q.; Bao, L.-B.; Zhao, X.-H.; Wang, C.-Y.; Zhou, S.; Wen, L.-H.; Fu, C.-B.; Gong, J.-M.; Qu, M.-R. Nicotinic acid supplementation in diet favored intramuscular fat deposition and lipid metabolism in finishing steers. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.S.; Son, G.H.; Kwon, E.G.; Chung, K.Y.; Jang, S.S.; Kim, U.H.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Park, B.K. Intramuscular fat formation in fetuses and the effect of increased protein intake during pregnancy in Hanwoo cattle. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2023, 65, 818–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, G.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Shi, Y.; Cheng, X.; Tang, X.; Le, G. Dietary methionine restriction regulated energy and protein homeostasis by improving thyroid function in high fat diet mice. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3718–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissa, A.F.; Tryndyak, V.; de Conti, A.; Melnyk, S.; Gomes, T.D.U.H.; Bianchi, M.L.P.; James, S.J.; Beland, F.A.; Antunes, L.M.G.; Pogribny, I.P. Effect of methionine-deficient and methionine-supplemented diets on the hepatic one-carbon and lipid metabolism in mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1502–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Hou, S.S.; Huang, W. Methionine requirements of male white Peking ducks from twenty-one to forty-nine days of age. Poult. Sci. 2006, 85, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, R.; Perruchot, M.-H.; Tesseraud, S.; Métayer-Coustard, S.; Baeza, E.; Mercier, Y.; Gondret, F. Methionine and cysteine deficiencies altered proliferation rate and time-course differentiation of porcine preadipose cells. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Liang, Y.; Coleman, D.; Li, Y.; Ding, H.; Liu, F.; Parys, C.; Cardoso, F.; Shen, X.; Loor, J. Methionine supplementation during a hydrogen peroxide challenge alters components of insulin signaling and antioxidant proteins in subcutaneous adipose explants from dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 2022, 105, 856–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Tang, J.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, B.; Cao, J.; Zhao, L.; Guo, Z.; Xie, M.; Zhou, Z.; Hou, S. Dietary methionine deficiency stunts growth and increases fat deposition via suppression of fatty acids transportation and hepatic catabolism in Pekin ducks. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hu, T.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. Effect of gene CRTC2 on the differentiation of subcutaneous preadipocytes in goats. Anim. Biosci. 2025, 38, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trim, W.V.; Lynch, L. Immune and non-immune functions of adipose tissue leukocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 22, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarese, G. The link between obesity and autoimmunity. Science 2023, 379, 1298–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.G.; Chen, J.; Mamane, V.; Ma, E.H.; Muhire, B.M.; Sheldon, R.D.; Shorstova, T.; Koning, R.; Johnson, R.M.; Esaulova, E.; et al. Methionine metabolism shapes t helper cell responses through regulation of epigenetic reprogramming. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 250–266.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, A.; Qubi, W.; Gong, C.; Li, X.; Xing, J.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Changes in the growth performance, serum biochemistry, rumen fermentation, rumen microbiota community, and intestinal development in weaned goats during rumen-protected methionine treatment. Front. Veter.-Sci. 2024, 11, 1482235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Qubi, W.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, W.; Lin, Y. ACADL promotes the differentiation of goat intramuscular adipocytes. Animals 2023, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Hu, R.; Gong, J.; Fang, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; He, Z.; Hou, D.-X.; Zhang, H.; He, J.; et al. Protection against metabolic associated fatty liver disease by protocatechuic acid. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2238959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Pan, F.; Jones, L.A.; Lim, M.M.; Griffin, E.A.; Sheline, Y.I.; Mintun, M.A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Mach, R.H. Evaluation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine staining as a sensitive and reliable method for studying cell proliferation in the adult nervous system. Brain Res. 2010, 1319, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Daifotis, H.A.; Nieman, K.M.; Fahrmann, J.F.; Lastra, R.R.; Romero, I.L.; Fiehn, O.; Lengyel, E. Adipocyte-induced FABP4 expression in ovarian cancer cells promotes metastasis and mediates carboplatin resistance. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1748–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzbeck, P.; Giordano, A.; Mondini, E.; Murano, I.; Severi, I.; Venema, W.; Cecchini, M.P.; Kershaw, E.E.; Barbatelli, G.; Haemmerle, G.; et al. Brown adipose tissue whitening leads to brown adipocyte death and adipose tissue inflammation. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, S.; Pessin, J.E. An adipocentric view of signaling and intracellular trafficking. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2002, 18, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, W.W.; Yen, P.M. Thermogenesis in adipose tissue activated by thyroid hormone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Shi, H.; Xiang, H.; Huang, L.; et al. Expression variation of CPT1A induces lipid reconstruction in goat intramuscular preadipocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, M.J. Clinical genetics of defects in thyroid hormone synthesis. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 23, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisoli, E.; Clementi, E.; Tonello, C.; Sciorati, C.; Briscini, L.; O Carruba, M. Effects of nitric oxide on proliferation and differentiation of rat brown adipocytes in primary cultures. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 125, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haczeyni, F.; Bell-Anderson, K.S.; Farrell, G.C. Causes and mechanisms of adipocyte enlargement and adipose expansion. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, S.R. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006, 4, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siersbæk, R.; Nielsen, R.; Mandrup, S. Transcriptional networks and chromatin remodeling controlling adipogenesis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 23, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, B.; Bellet, M.M.; Katada, S.; Astarita, G.; Hirayama, J.; Amin, R.H.; Granneman, J.G.; Piomelli, D.; Leff, T.; Sassone-Corsi, P. PER2 controls lipid metabolism by direct regulation of PPARγ. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, M.; Ouyang, J.; Tian, W.; Feng, D.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Loor, J.J. Ruminal epithelial cell proliferation and short-chain fatty acid transporters in vitro are associated with abundance of period circadian regulator 2 (PER2). J. Dairy. Sci. 2020, 103, 12091–12103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, S.P.; McCann, D.; Desai, M.; Rosenbaum, M.; Leibel, R.L.; Ferrante, A.W., Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1796–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; You, D.-B.; Lim, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-E.; Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-J.; Chung, N.-G.; Min, C.-K. Circulating levels of adipokines predict the occurrence of acute graft-versus-host disease. Immune Netw. 2015, 15, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, O.; Kuzmina, Z.; Winkler, A.; Kalhs, P.; Rabitsch, W.; Greinix, H. Adiponectin and resistin in acute and chronic graft-vs-host disease patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Croat. Med. J. 2016, 57, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuat, L.T.; Le, C.T.; Pai, C.-C.S.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Holtan, S.G.; Rashidi, A.; Parker, S.L.; Knights, D.; Luna, J.I.; Dunai, C.; et al. Obesity induces gut microbiota alterations and augments acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaay7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, V.P.T.H.; Masagounder, K.; Loewen, M.E. Critical transporters of methionine and methionine hydroxy analogue supplements across the intestine: What we know so far and what can be learned to advance animal nutrition. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2021, 255, 110908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Lin, W.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liu, W.; Yuan, Q. DNA demethylase ALKBH1 promotes adipogenic differentiation via regulation of HIF-1 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 298, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Lee, D.H.; Ham, S.; Oh, J.; Noh, J.-R.; Lee, Y.K.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, G.; Han, S.M.; Han, J.S.; et al. Targeted erasure of DNA methylation by TET3 drives adipogenic reprogramming and differentiation. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. Precision methionine feeding: A key strategy to enhance pig growth performance and meat quality. J. Anim. Sci Biotech. 2025, 16, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.; Li, C.; Horn, N.; Ajuwon, K.M. PPARγ activation inhibits endocytosis of claudin-4 and protects against deoxynivalenol-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction in IPEC-J2 cells and weaned piglets. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 375, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Horn, N.; Ajuwon, K.M. EPA and DHA inhibit endocytosis of claudin-4 and protect against deoxynivalenol-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction through PPARγ dependent and independent pathways in jejunal IPEC-J2 cells. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.M.; Loo, D.D.F.; Hirayama, B.A. Biology of human sodium glucose transporters. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 733–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, T.V.; Mäkinen, T.; Mäkela, T.P.; Saarela, J.; Virtanen, I.; Ferrell, R.E.; Finegold, D.N.; Kerjaschki, D.; Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Alitalo, K. Lymphatic endothelial reprogramming of vascular endothelial cells by the Prox-1 homeobox transcription factor. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 4593–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimesi, G.; Pujol-Giménez, J.; Kanai, Y.; Hediger, M.A. Sodium-coupled glucose transport, the SLC5 family, and therapeutically relevant inhibitors: From molecular discovery to clinical application. Pflug. Arch. 2020, 472, 1177–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-W.; Fang, W.-F.; Yang, Y.-M.; Lin, J.-D. High fatty acid-binding protein 4 expression associated with favorable clinical characteristics and prognosis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Endocr. Pathol. 2024, 35, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspari, R.R.; Reyna-Neyra, A.; Jung, L.; Torres-Manzo, A.P.; Hirabara, S.M.; Carrasco, N. The paradoxical lean phenotype of hypothyroid mice is marked by increased adaptive thermogenesis in the skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22544–22551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaher, A.R. An overview of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL). Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 1964684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandino, G.; Kaspari, R.R.; Spadaro, O.; Reyna-Neyra, A.; Perry, R.J.; Cardone, R.; Kibbey, R.G.; Shulman, G.I.; Dixit, V.D.; Carrasco, N. Pathogenesis of hypothyroidism-induced NAFLD is driven by intra- and extrahepatic mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9172–E9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilho, F.; Barros, L. Effect of supplementing a combination of lysine and methionine on growing cattle performance and carcass composition. J. Dairy. Sci. 2010, 93, 707. [Google Scholar]

| Primer Name | Accession Number | Primer Sequence | Tm/°C | Product Length/bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GADPH | NM_001285607.1 | F: GGTCGGAGTGAACGGATTTGG R: CATTGATGACGAGCTTCCCG | 60 | 197 |

| PPARγ | NM_001285658.1 | F: AAGCGTCAGGGTTCCACTATG R: GAACCTGATGGCGTTATGAGAC | 60 | 197 |

| FABP4 | NM_001285623.1 | F: GAAAGAAGTGGGTGTGGGCT R: TGGTGGTAGTGACACCGTTC | 60 | 317 |

| ATGL | NM_001285739.1 | F: GGAGCTTATCCAGGCCAATG R: TGCGGGCAGATGTCACTCT | 60 | 180 |

| C/EBPα | XM_018062278.1 | F: CCGTGGACAAGAACAGCAAC R: AGGCGGTCATTGTCACTGGT | 58 | 142 |

| C/EBPβ | XM_018062278.1 | F: AAGAAGACGGTGGACAAGC R: AACAAGTTCCGCAGGGTG | 65 | 204 |

| GLUT4 | NM_001314227.1 | F: TGCTCATTCTTGGACGGTTCT R: CATGGATTCCAAGCCTAGCAC | 59 | 176 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, J.; Gong, C.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xing, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y. Methionine Supplementation Benefits Lipogenesis in Goat Intramuscular Adipocytes, Likely by Inhibiting the Expression of SLC5A5. Animals 2025, 15, 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233450

Pan J, Gong C, Li X, Li Y, Xing J, Lin Y, Wang Y. Methionine Supplementation Benefits Lipogenesis in Goat Intramuscular Adipocytes, Likely by Inhibiting the Expression of SLC5A5. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233450

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Jin, Chengsi Gong, Xuening Li, Yanyan Li, Jiani Xing, Yaqiu Lin, and Youli Wang. 2025. "Methionine Supplementation Benefits Lipogenesis in Goat Intramuscular Adipocytes, Likely by Inhibiting the Expression of SLC5A5" Animals 15, no. 23: 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233450

APA StylePan, J., Gong, C., Li, X., Li, Y., Xing, J., Lin, Y., & Wang, Y. (2025). Methionine Supplementation Benefits Lipogenesis in Goat Intramuscular Adipocytes, Likely by Inhibiting the Expression of SLC5A5. Animals, 15(23), 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233450