Reestablishment and Conservation Implications of the Milu Deer Population in Poyang Lake

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Animals and Data Collection

2.2.1. Monitoring Milu Population and Acclimatization Process

2.2.2. Monitoring of the Released Milu Population Dynamics

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Acclimatization Process of Milu in the Poyang Lake Basin

3.2. Population Dynamics of Milu After Released in Poyang Lake

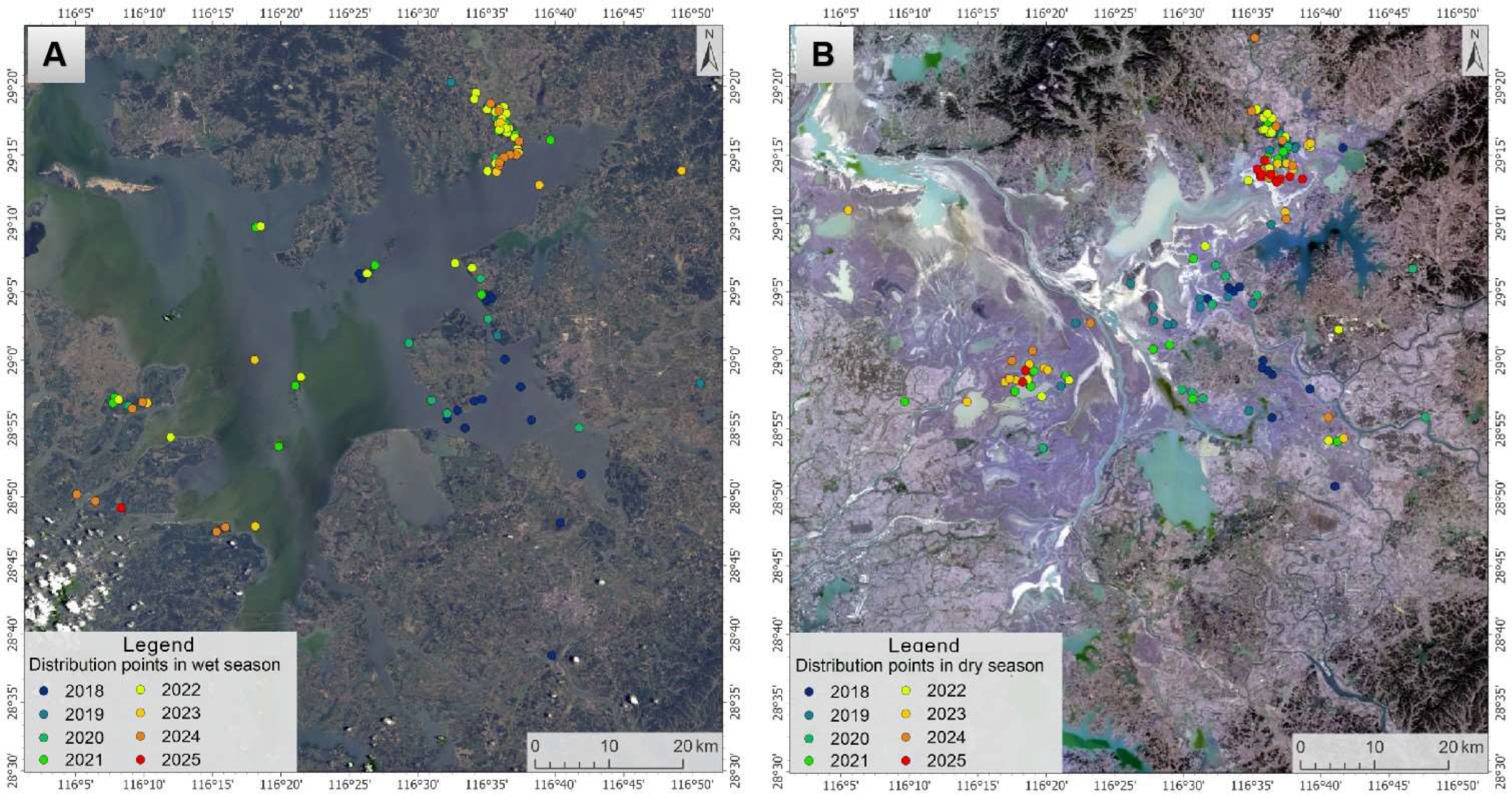

3.3. Distribution Characteristics of Milu After Released in Poyang Lake

4. Discussion

4.1. Establishment of the Milu Population in the Poyang Lake Basin and Factors Underlying Its Success

4.2. The Distribution and Population of Reintroduced Milu in Poyang Lake

4.3. Challenges in the Conservation of Milu in Poyang Lake

5. Conclusions and Conservation Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IUCN/SSC. Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations. Version 1.0; IUCN Species Survival Commission: Gland, Switzerland, 2013; p. T7121A22159785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN/SSC. Guidelines for Re-Introductions; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 1995; ISBN 2831704448. Available online: https://zooreach.org/Networks/RSG/IUCN%20Reintroduction%20guidelines.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Witmer, G. Re-introduction of elk in the United States. J. Penn. Acad. Sci. 1990, 64, 131–135. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44148971 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Seddon, P.J.; Strauss, W.M.; Innes, J. Animal translocations: What are they and why do we do them. In Reintroduction Biology: Integrating Science and Management; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2012; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soorae, P.S. Global Re-Introduction Perspectives: 2008; IUCN/SSC Re-Introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2008; Available online: https://iucn-ctsg.org/project/global-re-introduction-perspectives/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Soorae, P.S. Global Re-Introduction Perspectives: 2010; IUCN/SSC Re-Introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2010; Available online: https://iucn-ctsg.org/project/global-re-introduction-perspectives-2010/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Soorae, P.S. Global Re-Introduction Perspectives: 2011; IUCN/SSC Re-Introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2011; Available online: https://iucn-ctsg.org/project/global-re-introduction-perspectives-2011/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Soorae, P.S. Global Re-Introduction Perspectives: 2013; IUCN/SSC Re-Introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2013; Available online: https://iucn-ctsg.org/project/global-re-introduction-perspectives-2013/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Soorae, P.S. Global Re-Introduction Perspectives: 2016; IUCN/SSC Re-Introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2016; Available online: https://iucn-ctsg.org/project/global-re-introduction-perspectives-2016/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Soorae, P.S. Global Reintroduction Perspectives: 2018; IUCN/SSC Re-Introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2018; Available online: https://iucn.org/resources/publication/global-reintroduction-perspectives-2018 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Soorae, P.S. Global Conservation Translocation Perspectives: 2021; IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021; Available online: https://iucn-ctsg.org/project/global-conservation-translocation-perspectives-2021/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Vogt, K.; Korner-Nievergelt, F.; Signer, S.; Zimmermann, F.; Marti, I.; Ryser, A.; Molinari-Jobin, A.; Breitenmoser, U.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C. Long-Term Changes in Survival of Eurasian Lynx in Three Reintroduced Populations in Switzerland. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halley, D.J.; Rosell, F. The beaver’s reconquest of Eurasia: Status, population development and management of a conservation success. Mammal Rev. 2002, 32, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, M.; Beyer Jr, D.E.; Erb, J.D.; Gantchoff, M.G.; Kellner, K.F.; MacFarland, D.M.; Norton, D.C.; Patterson, B.R.; Price Tack, J.L.; Roell, B.J.; et al. Identifying potential gray wolf habitat and connectivity in the eastern USA. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 273, 109708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.G. Re-introduction of Père David’s deer “Milu” to Beijing, Dafeng & Shishou, China. In Global Re-Introduction Perspectives: 2013. Further Case Studies from Around the Globe; Soorae, P.S., Ed.; IUCN/SSC Re-Introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2013; pp. 143–147. Available online: https://iucn-ctsg.org/project/global-re-introduction-perspectives-2013/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Ma, K.; Liu, D.; Wei, R.; Zhang, G.; Xie, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H. Giant panda reintroduction: Factors affecting public support. Biodivers. Conserv. 2016, 25, 2987–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Du, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Cheng, H.; Lv, S.; Jia, T.; Zhang, J. Movement Range and Variation of Re-introduced Red-Crowned Cranes (Grus japonensis) in the Early Stages after Release in the Wild. Chin. J. Wildl. 2017, 38, 28–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luo, Z.; Hu, D. Assessing Fecal Microbial Diversity and Hormone Levels as Indicators of Gastrointestinal Health in Reintroduced Przewalski’s Horses (Equus ferus przewalskii). Animals 2024, 14, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, X.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Dong, R.; Huo, Z.; Yu, X. Survival rates of a reintroduced population of the Crested Ibis Nipponia nippon in Ningshan County (Shaanxi, China). Bird Conserv. Int. 2018, 28, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yao, H.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Thorbjarnarson, J.; Wang, X. Testing reintroduction as a conservation strategy for the critically endangered Chinese alligator: Movements and home range of released captive individuals. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 2586–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, S.; Tian, X.; Rong, K.; Ma, J. Genetic diversity and population genetic structure of Python bivittatus in China. J. For. Res. 2017, 28, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Huang, Q.; Yang, X.; Cui, X.; Wen, K.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Dai, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhu, L. Diet and environment drive the convergence of gut microbiome in wild-released giant pandas and forest musk deer. iScience 2025, 28, 112837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Guangxi: First Global Rewilding and Release of Francois’ Langurs. Guangxi For. 2017, 11, 7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtaishi, N.; Gao, Y. A review of the distribution of all species of deer (Tragulidae, Moschidae and Cervidae) in China. Mammal Rev. 1990, 20, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Harris, R.B. Elaphurus davidianus. IUCN Red List. Threat. Species; IUCN Red List: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; p. e.T7121A22159785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Tian, X.; Zhong, Z.; Li, P.; Sun, D.; Bai, J.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Reintroduction, distribution, population dynamics and conservation of a species formerly extinct in the wild: A review of thirty-five years of successful Milu (Elaphurus davidianus) reintroduction in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 31, e01860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, J.; Hu, H.; Li, P. Causes of endangerment or extinction of some mammals and its rele-vance to the reintroduction of Père David’s deer in the Dongting Lake drainage area. Biodivers. Sci. 2005, 13, 451–461. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wen, H.; Li, P.; Gao, D.; Chang, Q. Research on Recovery and Conservation of Wild Pere David’s Deer Population in China. Chin. J. Wildl. 2014, 35, 228–233. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhao, Y.W.; Lju, L.M. Protective Utilization and Function Estimate of Wetlands Ecosystem in Poyang Lake. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2004, 18, 196–200. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, L.; Yao, X.; Bai, L.; Zhang, Q. Analysis on the soil microbial biomass in typical hygrophilous vegetation of Poyang Lake. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2010, 30, 5033–5042. Available online: https://www.ecologica.cn/stxb/article/abstract/stxb200907010896 (accessed on 5 August 2025). (In Chinese).

- Fang, S.; Wang, S.; Ouyang, Q. Discussion on the Definition Standard of the Wet Season, Normal Season and Dry Season in Poyang Lake. J. China Hydrol. 2022, 42, 11–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R. Genetics and extinction. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 126, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchamp, F.; Clutton-Brock, T.; Grenfell, B. Inverse density dependence and the Allee effect. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.P.; Seddon, P.J. Directions in reintroduction biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzanowski, K.; Klich, D.; Olech, W. European Union needs urgent strategy for the European bison. Conserv. Lett. 2022, 15, e12923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley-Price, M.R. Animal Reintroductions: The Arabian Oryx in Oman; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; Available online: https://oa.mg/work/2104814038 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Gong, S.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y.; Fong, J.J.; Parham, J.F.; Shi, H.T. Integrating and updating wildlife conservation in China. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R915–R919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Corlett, R.T.; Ouyang, Z.; Blackmore, S. How can China protect 30% of its land? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2025, 40, 824–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, S.; Jiang, K. Home range characteristics of the released female milu (Père David’s deer, Elaphurus davidianus) population during different periods and effects of water submersion in Dongting Lake, China. Pak. J. Zool. 2022, 54, 1001–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebblewhite, M.; Merrill, E.H. Trade-offs between predation risk and forage differ between migrant strategies in a migratory ungulate. Ecology 2009, 90, 3445–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorquodale, S.M. Sex-specific movements and habitat use by elk in the Cascade Range of Washington. J. Wildl. Manag. 2003, 67, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuboi, C.; Hussain, S.A. Factors affecting forage selection by the endangered Eld’s deer and hog deer in the floating meadows of Barak-Chindwin Basin of North-east India. Mamm. Biol. 2016, 81, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasińska, M.; Krasiński, Z.A. European Bison: The Nature Monograph; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.; Tran, V.B.; Hoang, D.M.; Nguyen, T.A.M.; Nguyen, D.T.; Tran, V.T.; Long, B.; Meijaard, E.; Holland, J.; Wilting, A.; et al. Camera-trap evidence that the silver-backed chevrotain Tragulus versicolor remains in the wild in Vietnam. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Nukina, R.; Xie, Y.; Shibata, S. Public attitudes to urban wild deer (Cervus nippon) and management policies: A case study of Kyoto City, Japan. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 51, e02927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.L.; Cox, E.W.; Ballard, W.B.; Whitlaw, H.A.; Lenarz, M.S.; Custer, T.W.; Barnett, T.; Fuller, T.K. Pathogens, nutritional deficiency, and climate influences on a declining moose population. Wildl. Monogr. 2006, 166, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mei, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhang, N.; Guo, Y.; Wang, K.; Hao, Y.; Wang, D. Seasonal Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis) movements in the Poyang Lake, China: Implications on flexible management for aquatic animals in fluctuating freshwater ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Huang, S.L.; Hao, Y.; Turvey, S.T.; Gong, W.; Wang, D. Accelerating population decline of Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis). Biol. Conserv. 2012, 153, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Noss, R.F. Rewilding in the face of climate change. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 35, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapickis, R.; Griciuvienė, L.; Kibiša, A.; Paulauskas, A. Restitution and reintroduction of the European bison, Bison bonasus, in Lithuania: Review paper. Balt. For. 2025, 31, id797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.W.; Stahler, D.R.; MacNulty, D.R. Yellowstone Wolves: Science and Discovery in the World’s First National Park; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Population Size at the End of the Year | Number of Calves | Number of Deaths | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 9 | - | The founder population consisted of 10 individuals, one of which (a male) died during transport due to stress syndrome. | |

| 2014 | 12 | 3 | 0 | |

| 2015 | 15 | 3 | 0 | |

| 2016 | 17 | 4 | 2 | One male deer died from fighting, and one female deer died of digestive tract diseases. |

| 2017 | 21 | 5 | 1 | One female deer died of unknown causes. |

| 2018 | 51 | - | - | Secondary reintroduction (n = 30). First cohort (n = 47) released into the wild. |

| Year | Number of Sighting Events | Number of Sighted Individuals | Mean Number of Individuals Per Sighting Event | Number of Calves | Number of Dead Deer | Number of Milu Rescued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 30 | 155 | 7.75 | 10 | 2 | 3 |

| 2019 | 39 | 439 | 11.26 | 12 | 1 | 2 |

| 2020 | 26 | 220 | 8.46 | 8 | 2 | 2 |

| 2021 | 29 | 208 | 7.17 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| 2022 | 48 | 296 | 6.17 | 10 | 2 | 1 |

| 2023 | 23 | 118 | 5.13 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2024 | 30 | 178 | 5.93 | 4 | 0 | 12 |

| 2025 | 13 | 83 | 6.38 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 238 | 1697 | 7.28 | 52 | 10 | 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Xiong, B.; Zhong, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, D.; Feng, C.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, J.; et al. Reestablishment and Conservation Implications of the Milu Deer Population in Poyang Lake. Animals 2025, 15, 3446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233446

Cheng Z, Zhong Z, Xiong B, Zhong X, Ma J, Liu D, Feng C, Guo Q, Zhang Q, Bai J, et al. Reestablishment and Conservation Implications of the Milu Deer Population in Poyang Lake. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233446

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Zhibin, Zhenyu Zhong, Bin Xiong, Xinghua Zhong, Jialiang Ma, Daoli Liu, Chenmiao Feng, Qingyun Guo, Qingxun Zhang, Jiade Bai, and et al. 2025. "Reestablishment and Conservation Implications of the Milu Deer Population in Poyang Lake" Animals 15, no. 23: 3446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233446

APA StyleCheng, Z., Zhong, Z., Xiong, B., Zhong, X., Ma, J., Liu, D., Feng, C., Guo, Q., Zhang, Q., Bai, J., & Cheng, K. (2025). Reestablishment and Conservation Implications of the Milu Deer Population in Poyang Lake. Animals, 15(23), 3446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233446