Anti-Predator Strategies in Fish with Contrasting Shoaling Preferences Across Different Contexts

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin and Acclimation of Experimental Fish

2.2. Experimental Protocol and Determination

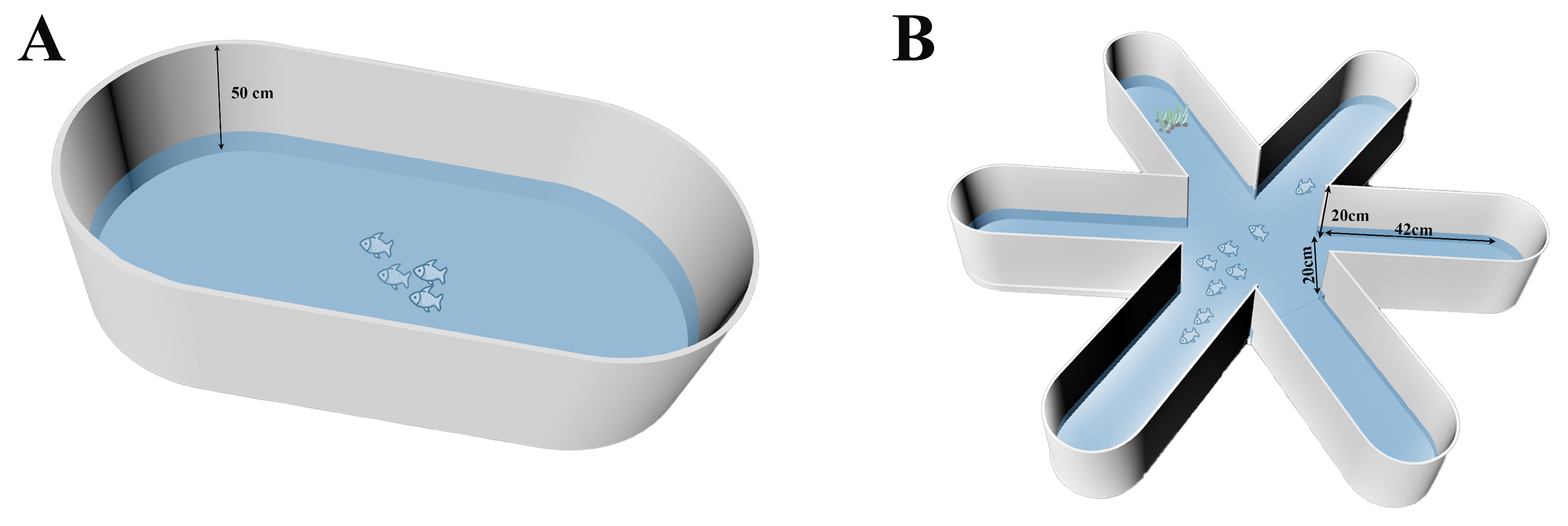

2.2.1. Experimental Device of Group Behavior in Open-Water Arena

2.2.2. Experimental Device of Group Behavior in Six-Arm Maze

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

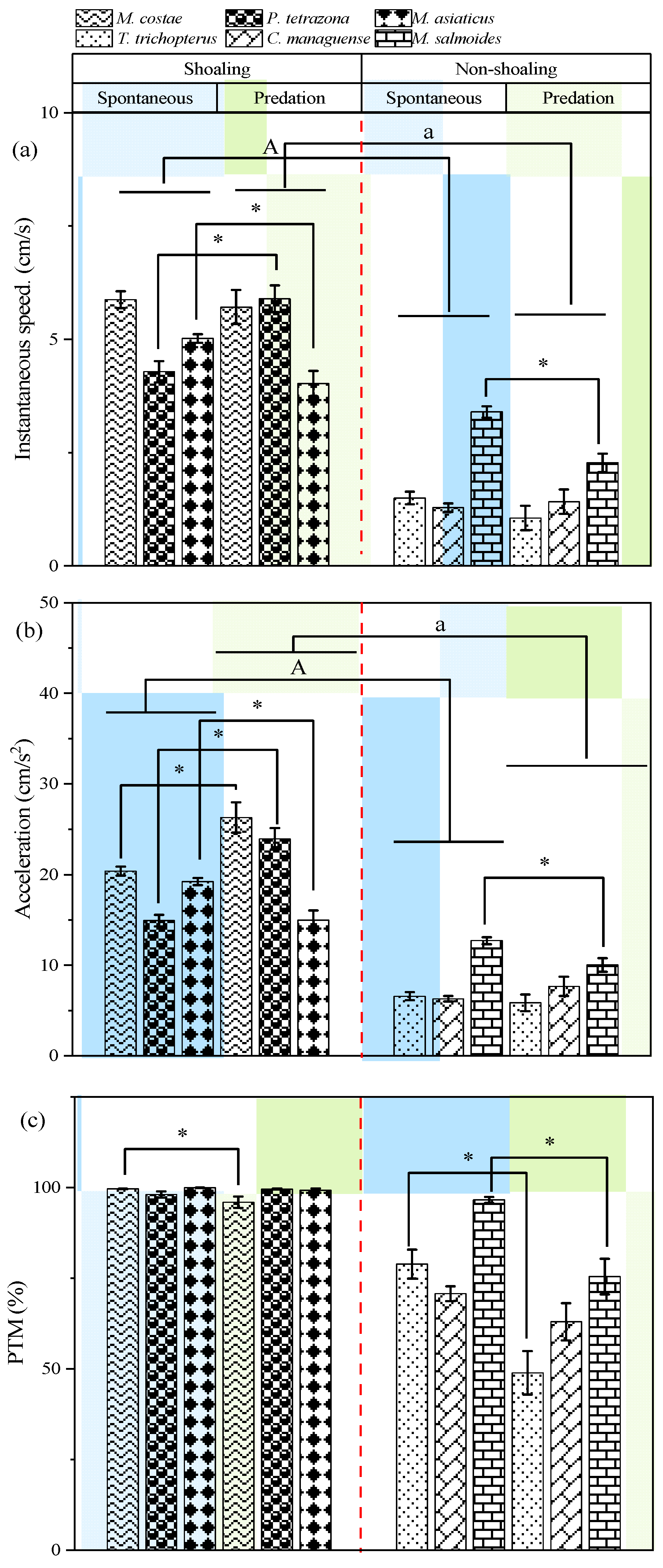

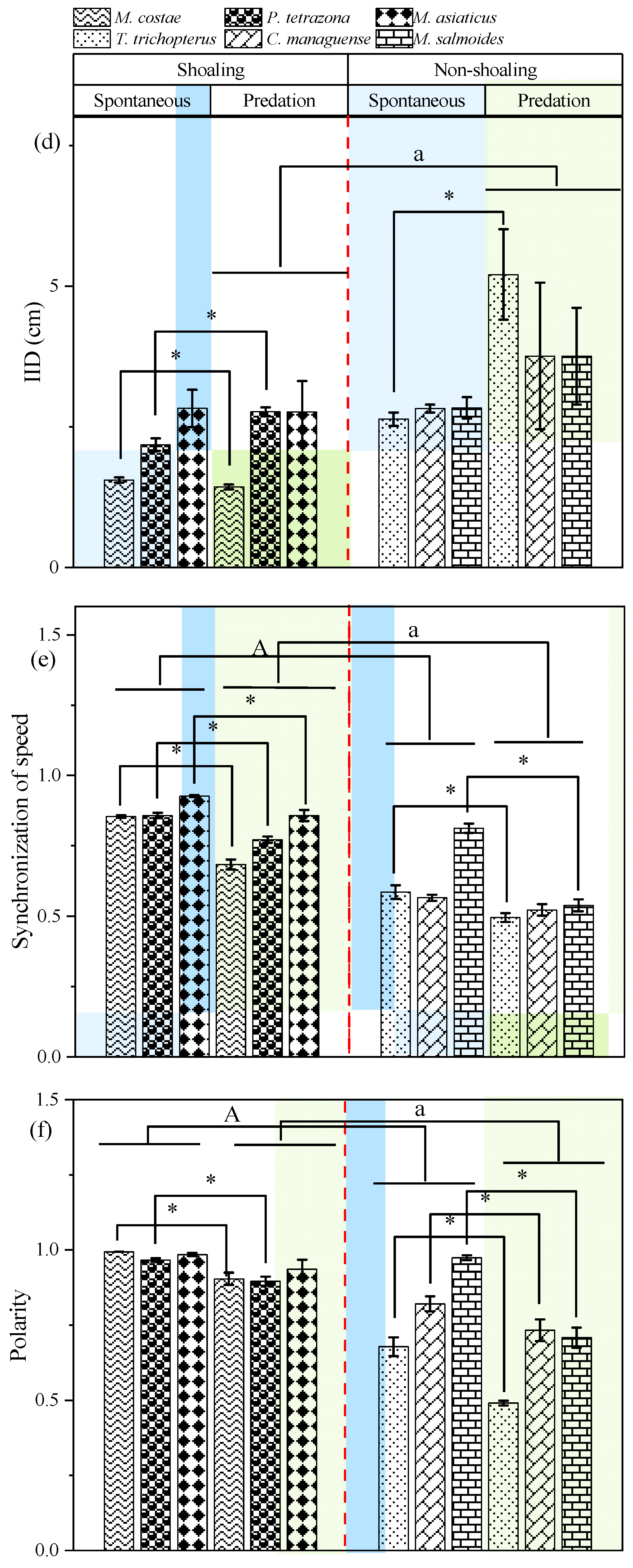

3.1. Behavioral Responses in Open-Water Arena

3.2. Behavioral Responses in Six-Arm Maze

4. Discussion

4.1. Anti-Predator Strategies in the Open-Water Conditions

4.2. Anti-Predation Strategies in the Six-Arm Maze

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Domenici, P.; Lefrançois, C.; Shingles, A. Hypoxia and the Antipredator Behaviours of Fishes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 362, 2105–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaliers, M.; Choleris, E. Antipredator Responses and Defensive Behavior: Ecological and Ethological Approaches for the Neurosciences. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2001, 25, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, C.C.; Tosh, C.R.; Neville, L.; Krause, J. The Confusion Effect—From Neural Networks to Reduced Predation Risk. Behav. Ecol. 2008, 19, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A.Y.; Quinn, T.P.; Myers, K.W.; Berdahl, A.M. Group Size Affects Predation Risk and Foraging Success in Pacific Salmon at Sea. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, C.; Bierbach, D.; Lukas, J.; Klamser, P.; Landgraf, T.; Klenz, H.; Habedank, M.; Arias-Rodriguez, L.; Krause, S.; Romanczuk, P.; et al. Fish Waves as Emergent Collective Antipredator Behavior. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 708–714.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Mamede, J.; Nomura, F. Dendropsophus Minutus (Hylidae) Tadpole Evaluation of Predation Risk by Fishing Spiders (Thaumasia Sp.: Pisauridae) Is Modulated by Size and Social Environment. J. Ethol. 2021, 39, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Sakai, Y.; Kuwamura, T. Effects of Group Behavior in the Predatory Raid on Damselfish Nests by the False Cleanerfish Aspidontus taeniatus. Ethology 2022, 128, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G. Why Individual Vigilance Declines as Group Size Increases. Anim. Behav. 1996, 51, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, T.L.; Bize, P.; Gineste, B.; Robin, J.-P.; Groscolas, R.; Viblanc, V.A. Disentangling the “Many-Eyes”, “Dilution Effect”, “Selfish Herd”, and “Distracted Prey” Hypotheses in Shaping Alert and Flight Initiation Distance in a Colonial Seabird. Behav. Process. 2023, 210, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Feng, G.; Wang, H.; Shen, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yao, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, W. The Influence of Shelter Type and Coverage on Crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) Predation by Catfish (Silurus asotus): A Controlled Environment Study. Animals 2024, 14, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xie, D.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Hu, S.; Liu, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, S. Influence of Water Temperature, Habitat Complexity and Light on the Predatory Performance of the Dark Sleeper Odontobutis potamophila (Günther, 1861). J. Freshwater Ecol. 2020, 35, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpwood, J.E.; Magurran, A.E.; Armstrong, J.D.; Griffiths, S.W. Minnows and the Selfish Herd: Effects of Predation Risk on Shoaling Behaviour Are Dependent on Habitat Complexity. Anim. Behav. 2008, 76, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rilov, G.; Figueira, W.F.; Lyman, S.J.; Crowder, L.B. Complex Habitats May Not Always Benefit Prey: Linking Visual Field with Reef Fish Behavior and Distribution. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 329, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakan, E.P.; Allan, B.J.M.; Illing, B.; Hoey, A.S.; McCormick, M.I. Habitat Complexity and Predator Odours Impact on the Stress Response and Antipredation Behaviour in Coral Reef Fish. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, R.J.; Kambestad, M.; Berhe, S.; Birnie-Gauvin, K.; Cooke, S.J.; Dahlmo, L.S.; Eldøy, S.H.; Davidsen, J.G.; Hanssen, E.M.; Sortland, L.K. The Role of Habitat in Predator–Prey Dynamics with Applications to Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e14354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, I.; Bhat, A. The Impact of Predators and Vegetation on Shoaling in Wild Zebrafish. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 240760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encel, S.A.; Schaerf, T.M.; Lizier, J.T.; Ward, A.J. Locomotion, Interactions and Information Transfer Vary According to Context in a Cryptic Fish Species. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2021, 75, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Tian, Z. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Molecular Mechanisms Responsive to Acute Cold Stress in the Tropical Stenothermal Fish Tiger Barb (Puntius tetrazona). BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.P.A.; Lustosa-Costa, S.Y.; Lima, R.M.O.; Barbosa, J.E.D.L.; Menezes, R.F. First Record of Moenkhausia Costae (Steindachner 1907) in the Paraíba Do Norte Basin after the São Francisco River Diversion. Biota Neotrop. 2021, 21, e20201049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Song, Z. Hatchery Release Programme Modified the Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Wild Chinese Sucker (Myxocyprinus asiaticus) in the Upper Yangtze River. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwater Ecosyst. 2022, 32, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lin, Z.; Xiao, F. Role of Body Size and Shape in Animal Camouflage. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degani, G. Brain Control Reproduction by the Endocrine System of Female Blue Gourami (Trichogaster trichopterus). Biology 2020, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, C.; Chen, X.; Zhong, Z.; Jiang, Y. Physiological Responses to Salinity Stress in the Managua Cichlid, Cichlasoma managuense. Aquacult. Res. 2020, 51, 4387–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T14925-2001; Laboratory Animal—Requirements of Environment and Housing Facilities. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2001.

- Pérez-Escudero, A.; Vicente-Page, J.; Hinz, R.C.; Arganda, S.; De Polavieja, G.G. idTracker: Tracking Individuals in a Group by Automatic Identification of Unmarked Animals. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ferrero, F.; Bergomi, M.G.; Hinz, R.C.; Heras, F.J.; De Polavieja, G.G. Idtracker. Ai: Tracking All Individuals in Small or Large Collectives of Unmarked Animals. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, J.W.; Boogert, N.J.; Sridhar, V.H.; Couzin, I.D.; Manica, A. Consistent Individual Differences Drive Collective Behavior and Group Functioning of Schooling Fish. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 2862–2868.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S. Effects of Group Size on Schooling Behavior in Two Cyprinid Fish Species. Aquat. Biol. 2016, 25, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcourt, J.; Poncin, P. Shoals and Schools: Back to the Heuristic Definitions and Quantitative References. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2012, 22, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Wu, H.; Kuang, L.; Fu, S.-J. The Behavioral Response of Prey Fish to Predators: The Role of Predator Size. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, J.; Fu, S. Effects of Starve and Shelter Availability on the Group Behavior of Two Freshwater Fish Species (Chindongo demasoni and Spinibarbus sinensis). Animals 2024, 14, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, C.C.; Laskowski, K.L. A Multi-Scale Review of the Dynamics of Collective Behaviour: From Rapid Responses to Ontogeny and Evolution. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2023, 378, 20220059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumoto, N.; Miyata, S.; Pratt, S.C. Inferring Collective Behaviour from a Fossilized Fish Shoal. Proc. R. Soc. B 2019, 286, 20190891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Tang, Z.-H.; Fu, S.-J. Numerical Ability in Fish Species: Preference between Shoals of Different Sizes Varies among Singletons, Conspecific Dyads and Heterospecific Dyads. Anim. Cogn. 2019, 22, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, L.E.; McCormick, M.I.; Johansen, J.L.; Domenici, P. Social Familiarity Improves Fast-Start Escape Performance in Schooling Fish. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demandt, N.; Bierbach, D.; Kurvers, R.H.J.M.; Krause, J.; Kurtz, J.; Scharsack, J.P. Parasite Infection Impairs the Shoaling Behaviour of Uninfected Shoal Members under Predator Attack. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2021, 75, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Shi, Q.; Liu, Y. Modeling and Simulation of the Fish Collective Behavior with Risk Perception and Startle Cascades. Phys. A 2025, 659, 130337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horka, P.; Vlachova, M. The Effect of Turbidity on the Behavior of Bleak (Alburnus alburnus). Fishes 2023, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiñaga, J.; Jin, S.; Pesati, I.; Laskowski, K.L. Behavioral Responses of a Clonal Fish to Perceived Predation Risk. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M. Schooling Fish from a New, Multimodal Sensory Perspective. Animals 2024, 14, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penry-Williams, I.L.; Brown, C.; Ioannou, C.C. Visual Lateralisation in Female Guppies Poecilia reticulata Demonstrates Social Conformity but Is Reduced When Observing a Live Predator Andinoacara pulcher. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, S.; Borcherding, J. Does Social Context Affect Boldness in Juveniles? Curr. Zool. 2017, 63, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhu, T.; Wu, X.; Li, X. Behavioral Characteristics of Largefin Longbarbel Catfish Hemibagrus macropterus: Effects of Sex and Body Size on Aggression and Shelter Selection. Animals 2025, 15, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesto, M.; Jokumsen, A. Effects of Simple Shelters on Growth Performance and Welfare of Rainbow Trout Juveniles. Aquaculture 2022, 551, 737930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, B.; Yu, L.; Liu, D.; Wang, F.; Lu, Y. Selection of Shelter Shape by Swimming Crab (Portunus trituberculatus). Aquacult. Rep. 2021, 21, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, B.; Yu, L.; Wang, F. Shelter Color Selection of Juvenile Swimming Crabs (Portunus trituberculatus). Fishes 2022, 7, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartland, L.A.; Firth, J.A.; Laskowski, K.L.; Jeanson, R.; Ioannou, C.C. Sociability as a Personality Trait in Animals: Methods, Causes and Consequences. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Fu, S.; Nadler, L.E.; Killen, S.S.; Zhou, K.-Y.; Zheng, S.-L.; Fu, C. Social Conditions Alter the Growth, Metabolic Rate, Behavioral Traits, and Food-Shelter Preferences in the Juvenile Qingbo Spinibarbus sinensis. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2025, 79, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbers, C.; Nagelkerken, I.; Govers, L.; van de Kerk, M.; Oldenburger, J.; de Brouwer, J. Habitat Type and Schooling Interactively Determine Refuge-Seeking Behavior in a Coral Reef Fish throughout Ontogeny. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 437, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavík, O.; Maciak, M.; Horký, P. Shelter Use of Familiar and Unfamiliar Groups of Juvenile European Catfish Silurus glanis. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 142, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, C.C.; Guttal, V.; Couzin, I.D. Predatory Fish Select for Coordinated Collective Motion in Virtual Prey. Science 2012, 337, 1212–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor Being Measured | Formula | Variables Used in Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Instantaneous speed | where x(t) and y(t) are the x- and y-coordinates of each fish at time t, and dt is the time interval between consecutive frames (i.e., 1/15 s) [28]. | |

| Swimming acceleration | where v(t) and v(t − 1) are the velocities of each fish at times t and t − 1, respectively, and dt is the time interval between consecutive frames (i.e., 1/15 s). | |

| Synchronization of speed | where vi and vj are the instantaneous speeds of the i-th and j-th fish in the group [29]. | |

| Inter-individual distance (IID) | where IID is the distance between individuals (cm), xi and xj are the abscissa values of the i-th and j-th fish in the shoal at time t, and yi and yj are the ordinate values of the i-th and j-th fish in the shoal at time t. | |

| Polarity (P) | where vi(t) is the motion vector of the individual fish i per unit time, and the motion direction is from the coordinate point at time t − 1 to the position coordinate point at time t. n denotes the number of members of the population (i.e., n = 4 in this study). | |

| Percent time spent moving (PTM) | When the swimming speed of fish exceeds 1.75 cm/s, it is regarded as moving state, and if the swimming speed is less than 1.75 cm/s, it is regarded as stationary state [30]. Where T1 represents the total time for fish to swim, and T2 represents the total video shooting time (spontaneous swimming time is 300 s, escape swimming time is 12 s). |

| Instantaneous Speed | Instantaneous Acceleration | Percent Time Spent Moving | Inter-Individual Distance | Synchronization of Speed | Polarity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoaling, S | F1,4 = 27.924 p = 0.006 * | F1,4 = 23.536 p = 0.008 * | F1,4 = 14.494 p = 0.019 * | F1,4 = 7.890 p = 0.048 * | F1,4 = 17.385 p = 0.014 * | F1,4 = 7.496 p = 0.052 |

| Predation, P | F1,232 = 1.243 p = 0.266 | F1,232 = 6.161 p = 0.014 * | F1,232 = 31.345 p < 0.001 * | F1,232 = 6.212 p = 0.013 * | F1,232 = 131.794 p < 0.001 * | F1,232 = 86.613 p < 0.001 * |

| S × P | F1,232 = 4.626 p = 0.033 * | F1,232 = 13.32 p < 0.001 * | F1,232 = 25.642 p < 0.001 * | F1,232 = 4.313 p = 0.039 * | F1,232 = 1.652 p = 0.200 | F1,232 = 17.240 p < 0.001 * |

| Center Density | Shelter Density | IC | Shuttling Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoaling, S | F1,4.002 = 0.820 p = 0.416 | F1,3.994 = 0.794 p = 0.423 | F1,3.994 = 10.503 p = 0.032 * | F1,4.004 = 0.231 p = 0.656 |

| Predation, P | F1,228.002 = 0.569 p = 0.452 | F1,227.994 = 0.064 p = 0.801 | F1,227.995 = 0.915 p = 0.340 | F1,227.004 = 46.961 p < 0.001 * |

| S × P | F1,232 = 13.666 p < 0.001 * | F1,232 = 3.573 p = 0.060 | F1,227.995 = 2.385 p = 0.124 | F1,228.004 = 0.477 p = 0.491 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Duan, X.; Fu, S. Anti-Predator Strategies in Fish with Contrasting Shoaling Preferences Across Different Contexts. Animals 2025, 15, 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233447

Lu Z, Li W, Zhang J, Duan X, Fu S. Anti-Predator Strategies in Fish with Contrasting Shoaling Preferences Across Different Contexts. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233447

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Zixi, Wuxin Li, Jiuhong Zhang, Xinbin Duan, and Shijian Fu. 2025. "Anti-Predator Strategies in Fish with Contrasting Shoaling Preferences Across Different Contexts" Animals 15, no. 23: 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233447

APA StyleLu, Z., Li, W., Zhang, J., Duan, X., & Fu, S. (2025). Anti-Predator Strategies in Fish with Contrasting Shoaling Preferences Across Different Contexts. Animals, 15(23), 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233447