GWAS Reveals Key Candidate Genes Associated with Milk-Production in Saanen Goats

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Resequencing of the Whole Genome

2.3. Genome-Wide Association Study

2.4. Go Enrichment and Kegg Pathway Analysis

2.5. Correlation Analysis

2.6. Cell Culture and Transfection

2.7. Rt-Qpcr

2.8. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.9. Edu Assay

2.10. Annexin-V Staining

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

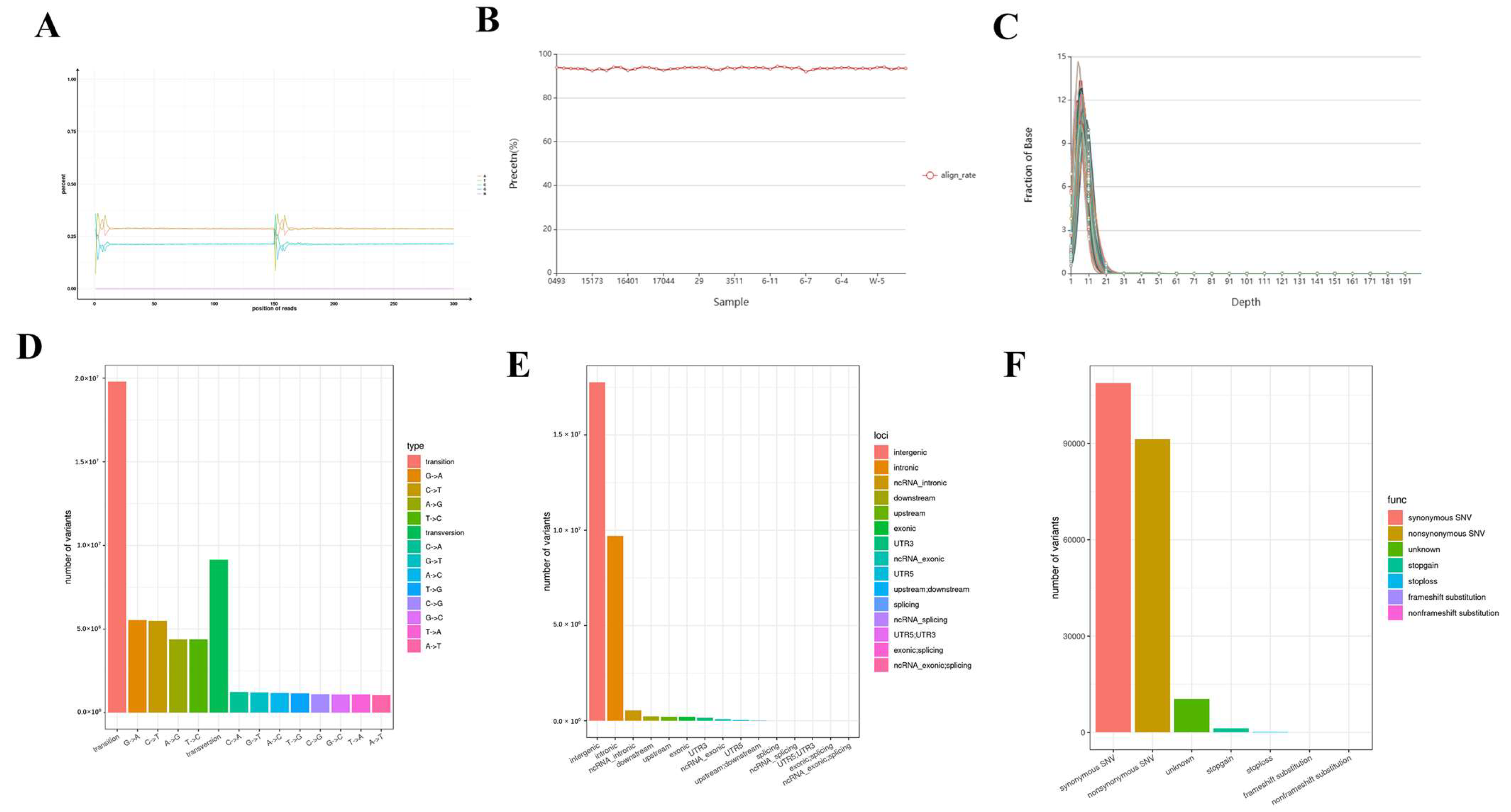

3.1. Overview of Sequencing Data

3.2. Comparison of Reference Genome Maps

3.3. Identification of Snp Mutations

3.4. Go and Kegg Analysis

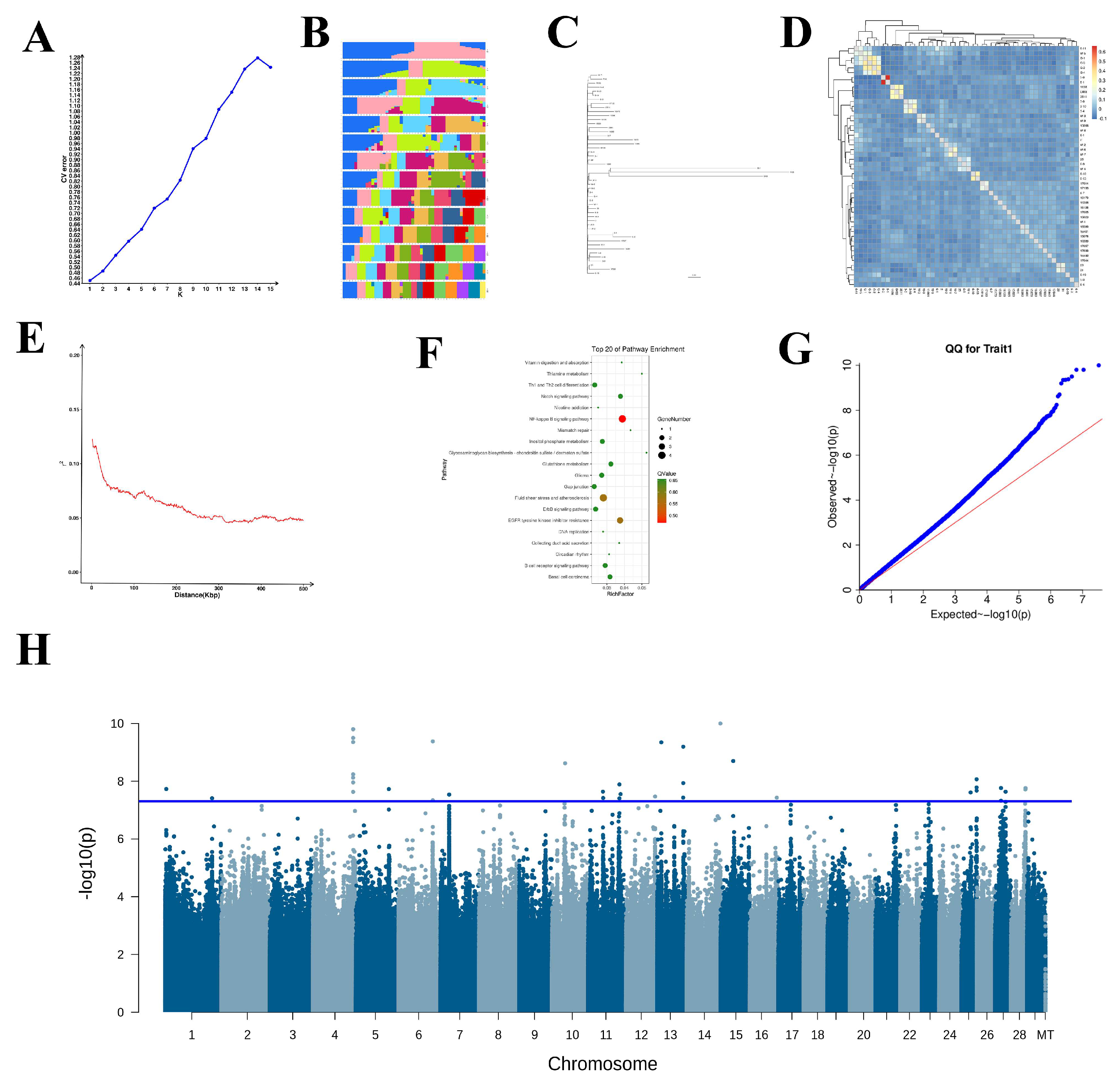

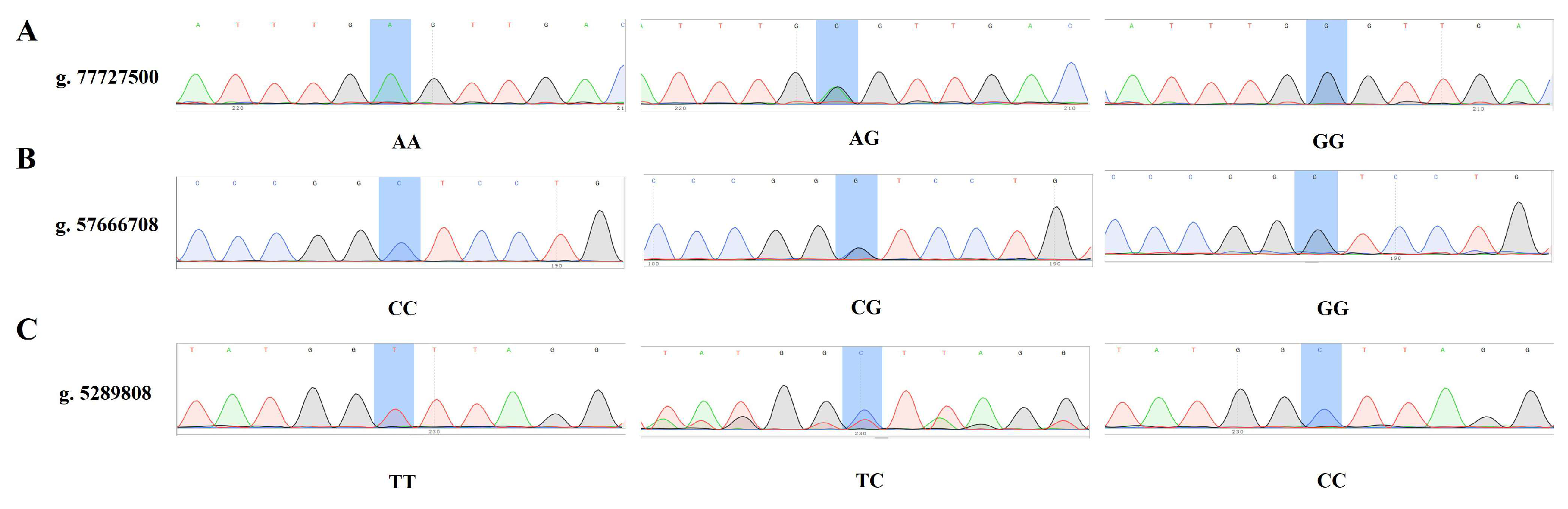

3.5. Validation of Snps Through Association Analysis

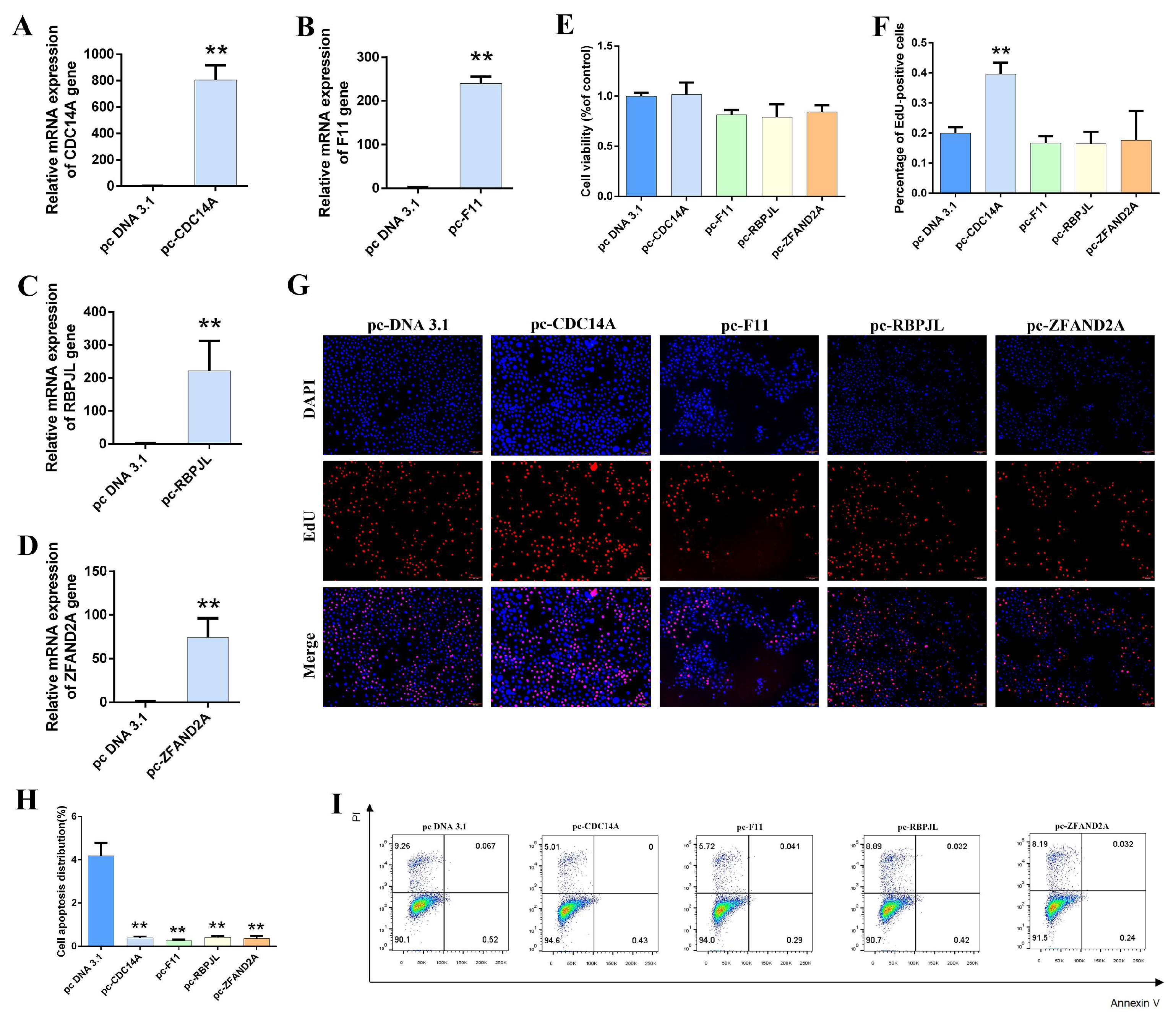

3.6. Effect of Overexpressing Candidate Genes on the Lactation Performance of Gmecs

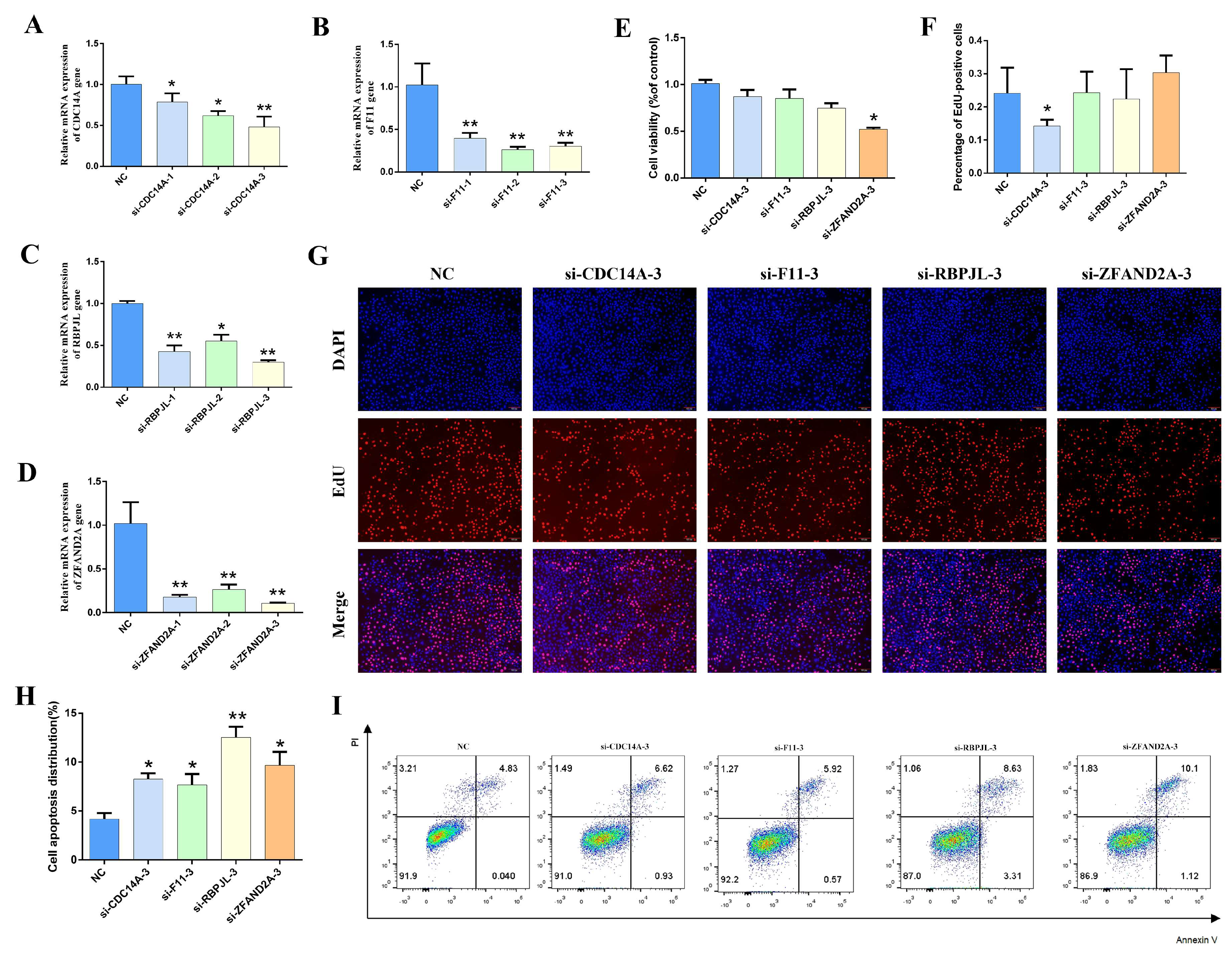

3.7. Effect of Silent Candidate Genes on the Lactation Performance of Gmecs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| circRNA | circular RNA |

| GMECs | Goat mammary epithelial cells |

| GCTA | Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis |

| GS | Genomic selection |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| He | Heterozygosity |

| HGVS | Human Genome Variation Society |

| indel | Insertion–deletion |

| MAS | Marker-assisted selection |

| MAF | Minor allele frequency |

| PIC | Polymorphism information content |

| SNPs | Single-nucleotide polymorphisms |

| WGCNA | Weighted gene co-expression network analysis |

References

- Yao, X.; Li, J.; Fu, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Nanaei, H.A.; Shah, A.M.; Zhang, Z.; Bian, P.; Zhou, S.; et al. Genomic Landscape and Prediction of Udder Traits in Saanen Dairy Goats. Animals 2025, 15, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.N.; Newton, M.G.; Stenhouse, C.; Connolly, E.; Hissen, K.L.; Horner, S.; Wu, G.; Foxworth, W.; Bazer, F.W. Dietary citrulline supplementation enhances milk production in lactating dairy goats. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabjeesh, S.J.; Sabastian, C.; Gal-Garber, O.; Shamay, A. Effect of photoperiod and heat stress in the third trimester of gestation on milk production and circulating hormones in dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Luo, Y.; Li, X.; Tian, J.; Tao, S.; Hua, C.; Geng, Y.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, R. Negative effects of long-term feeding of high-grain diets to lactating goats on milk fat production and composition by regulating gene expression and DNA methylation in the mammary gland. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Chen, M.; Sooranna, S.R.; Shi, D.; Liu, Q.; Li, H. The emerging roles of circRNAs in traits associated with livestock breeding. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2023, 14, e1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F.H.; Cao, Y.H.; Liu, G.J.; Luo, L.Y.; Lu, R.; Liu, M.J.; Li, W.R.; Zhou, P.; Wang, X.H.; Shen, M.; et al. Whole-Genome Resequencing of Worldwide Wild and Domestic Sheep Elucidates Genetic Diversity, Introgression, and Agronomically Important Loci. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022, 39, msab353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Duan, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xu, N.; Zhao, Y. Caprine and Ovine Genomic Selection-Progress and Application. Animals 2024, 14, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shi, C.; Kamalibieke, J.; Gong, P.; Mu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Lv, X.; Wang, W.; Luo, J. Whole genome and transcriptome analyses in dairy goats identify genetic markers associated with high milk yield. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 292, 139192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.J.; Wu, H.Y.; Chiang, P.H.; Hsu, Y.T.; Weng, P.Y.; Yu, T.H.; Li, C.Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Dai, H.J.; Tsai, H.Y.; et al. Decoding and reconstructing disease relations between dry eye and depression: A multimodal investigation comprising meta-analysis, genetic pathways and Mendelian randomization. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 69, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, H.; Akhatayeva, Z.; Liu, H.; Lin, C.; Han, X.; Lu, X.; Lan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, C. Novel indel variations of the sheep FecB gene and their effects on litter size. Gene 2021, 767, 145176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Nie, X.; Wu, Q.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fang, K.; et al. GWAS identifies two important genes involved in Chinese chestnut weight and leaf length regulation. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 2387–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Liu, R.; Zhao, D.; He, Z.; Li, W.; Zheng, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Liu, D.; Feng, F.; et al. Large-scale genomic and transcriptomic analyses elucidate the genetic basis of high meat yield in chickens. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 55, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahito, J.H.; Zhang, H.; Gishkori, Z.G.N.; Ma, C.; Wang, Z.; Ding, D.; Zhang, X.; Tang, J. Advancements and Prospects of Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) in Maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massender, E.; Oliveira, H.R.; Brito, L.F.; Maignel, L.; Jafarikia, M.; Baes, C.F.; Sullivan, B.; Schenkel, F.S. Genome-wide association study for milk production and conformation traits in Canadian Alpine and Saanen dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 1168–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massender, E.; Brito, L.F.; Maignel, L.; Oliveira, H.R.; Jafarikia, M.; Baes, C.F.; Sullivan, B.; Schenkel, F.S. Single-step genomic evaluation of milk production traits in Canadian Alpine and Saanen dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 2393–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, M.; Sun, E.; Lu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, G.; et al. Investigation of selection signatures of dairy goats using whole-genome sequencing data. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Das, S.P.; Choudhury, B.U.; Kumar, A.; Prakash, N.R.; Verma, R.; Chakraborti, M.; Devi, A.G.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Das, R.; et al. Advances in genomic tools for plant breeding: Harnessing DNA molecular markers, genomic selection, and genome editing. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wu, W.; Tan, L.; Long, Q.; Xia, H.; Hu, M. The effects of sequencing strategies on Metagenomic pathogen detection using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, A.; Hu, H.; Wang, L.; Gong, M.; Yang, Q.; Liu, A.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. The efficient phasing and imputation pipeline of low-coverage whole genome sequencing data using a high-quality and publicly available reference panel in cattle. Anim. Res. One Health 2023, 1, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasik, K.; Berisa, T.; Pickrell, J.K.; Li, J.H.; Fraser, D.J.; King, K.; Cox, C. Comparing low-pass sequencing and genotyping for trait mapping in pharmacogenetics. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.C.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-generation PLINK: Rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Niu, M.; Cui, J.; Che, S.; Liu, Y.; An, X.; Cao, B. Analyses of circRNA profiling during the development from pre-receptive to receptive phases in the goat endometrium. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Ma, X.; Wei, S.; Qiu, D.; Wilson, I.W.; Wu, P.; Tang, Q.; Liu, L.; Dong, S.; Zu, W. De novo transcriptome sequencing and digital gene expression analysis predict biosynthetic pathway of rhynchophylline and isorhynchophylline from Uncaria rhynchophylla, a non-model plant with potent anti-alzheimer’s properties. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Cheng, Z.; Xu, G.; Li, F.; Bu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; An, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress exacerbates microplastics-induced toxicity in animal cells. Food Res. Int. 2024, 175, 113818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budu-Aggrey, A.; Kilanowski, A.; Sobczyk, M.K.; Shringarpure, S.S.; Mitchell, R.; Reis, K.; Reigo, A.; Mägi, R.; Nelis, M.; Tanaka, N.; et al. European and multi-ancestry genome-wide association meta-analysis of atopic dermatitis highlights importance of systemic immune regulation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Boatwright, J.L.; Boyles, R.E.; Brenton, Z.W.; Kresovich, S. Identification of pleiotropic loci mediating structural and non-structural carbohydrate accumulation within the sorghum bioenergy association panel using high-throughput markers. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1356619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Du, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, R.; Ai, N.; Feng, G.; Li, C. Genetic dissection of lint percentage in short-season cotton using combined QTL mapping and RNA-seq. TAG Theor. Appl. Genet. Theor. Und Angew. Genet. 2023, 136, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Yuan, L.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Peng, J.; Tian, H.; Li, F.; Wang, W. Application of multi-omics technology in pathogen identification and resistance gene screening of sheep pneumonia. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, P.H.; Cao, T.N.M.; Tran, T.T.; Matsumoto, T.; Akada, J.; Yamaoka, Y. Identification of genetic determinants of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolates in Vietnam by high-throughput sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Hu, X.; Wan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, X.; Cai, M.; Yu, T.; Xiao, J. A unified framework for cell-type-specific eQTL prioritization by integrating bulk and scRNA-seq data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 112, 332–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.P.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Wolf, V.; Laithier, C.; El Jabri, M.; Michenet, A.; Boussaha, M.; Taussat, S.; Fritz, S.; Delacroix-Buchet, A.; et al. Sequence-based GWAS, network and pathway analyses reveal genes co-associated with milk cheese-making properties and milk composition in Montbéliarde cows. Genet. Sel. Evol. GSE 2019, 51, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Cui, M.; Wang, Z.; Sun, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Lai, S.; Jia, X. Genome-Wide Association Studies of Growth Trait Heterosis in Crossbred Meat Rabbits. Animals 2024, 14, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Saeed, S.; Khan, M.H.U.; Fan, C.; Ahmar, S.; Arriagada, O.; Shahzad, R.; Branca, F.; Mora-Poblete, F. Advances and Challenges for QTL Analysis and GWAS in the Plant-Breeding of High-Yielding: A Focus on Rapeseed. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, H.; Minogue, C.E.; Jayaraman, D.; Richards, A.L.; Kwiecien, N.W.; Siahpirani, A.F.; Rajasekar, S.; Maeda, J.; Garcia, K.; Del Valle-Echevarria, A.R.; et al. A proteomic atlas of the legume Medicago truncatula and its nitrogen-fixing endosymbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, A.; Kohane, I.S. A SNP-centric database for the investigation of the human genome. BMC Bioinform. 2004, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.H.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.K.; Fan, Y.X.; Qiao, X.; Gong, G.; Yan, X.C.; Zhang, L.T.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, R.J.; et al. Progress in goat genome studies. Yi Chuan Hered. 2019, 41, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teissier, M.; Larroque, H.; Brito, L.F.; Rupp, R.; Schenkel, F.S.; Robert-Granié, C. Genomic predictions based on haplotypes fitted as pseudo-SNP for milk production and udder type traits and SCS in French dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11559–11573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Luo, H.; Fu, X.; Zhang, G.; Clark, E.L.; Wang, F.; Dalrymple, B.P.; Oddy, V.H.; Vercoe, P.E.; Wu, C.; et al. A Developmental Gene Expression Atlas Reveals Novel Biological Basis of Complex Phenotypes in Sheep. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2025, 23, qzaf020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Hou, J.; Gao, T.; Lei, Y.; Li, G.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, B. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms g.151435C>T and g.173057T>C in PRLR gene regulated by bta-miR-302a are associated with litter size in goats. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 1477–1483.e1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.X.; An, X.P.; Song, Y.X.; Wang, J.G.; Ma, T.; Han, P.; Fang, F.; Cao, B.Y. Combined effects of four SNPs within goat PRLR gene on milk production traits. Gene 2013, 529, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, G.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ruan, T.; Yang, X.; Zhuo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ou, Y.; Zhao, X.; et al. DNAH3 deficiency causes flagellar inner dynein arm loss and male infertility in humans and mice. eLife 2024, 13, RP96755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Ha, K.; Lu, G.; Fang, X.; Cheng, R.; Zuo, Q.; Zhang, P. Cdc14A and Cdc14B Redundantly Regulate DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 35, 3657–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Cheng, B.Y.; Edwards, D.L.; Gonzalez, J.C.; Chiu, D.K.; Zheng, H.; Scallan, C.; Guo, X.; Tan, G.S.; Coffey, G.P.; et al. Sialylated IgG induces the transcription factor REST in alveolar macrophages to protect against lung inflammation and severe influenza disease. Immunity 2025, 58, 182–196.e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zuo, M.; Zhao, J.; Niu, T.; Hu, A.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X. DPHB inhibits osteoclastogenesis by suppressing NF-κB and MAPK signaling and alleviates inflammatory bone destruction. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 152, 114377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ding, X.; Yue, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Lei, J.; Zang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Tao, P. A rare stop-gain SNP mutation in BrGL2 causes aborted trichome development in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). TAG. Theor. Appl. genetics. Theor. Und Angew. Genet. 2025, 138, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, A.; Belyantseva, I.A.; Beirl, A.J.; Fenollar-Ferrer, C.; Bashir, R.; Bukhari, I.; Bouzid, A.; Shaukat, U.; Azaiez, H.; Booth, K.T.; et al. CDC14A phosphatase is essential for hearing and male fertility in mouse and human. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 780–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partscht, P.; Uddin, B.; Schiebel, E. Human cells lacking CDC14A and CDC14B show differences in ciliogenesis but not in mitotic progression. J. Cell Sci. 2021, 134, jcs255950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Khan, A.; Xiao, J.; Ma, Y.; Ma, J.; Gao, J.; Cao, Z. Role of the JAK-STAT Pathway in Bovine Mastitis and Milk Production. Animals 2020, 10, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Fang, M.; Sun, S.; Wang, G.; Fu, S.; Sun, B.; Tong, J. Blockade of the Arid5a/IL-6/STAT3 axis underlies the anti-inflammatory effect of Rbpjl in acute pancreatitis. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Liu, A.; Sasaki, F.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Takayanagi, H.; Saito, M.; Nakashima, T. Fam102a translocates Runx2 and Rbpjl to facilitate Osterix expression and bone formation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, S.; Bono, H. Meta-Analysis of Heat-Stressed Transcriptomes Using the Public Gene Expression Database from Human and Mouse Samples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vailati-Riboni, M.; Coleman, D.N.; Lopreiato, V.; Alharthi, A.; Bucktrout, R.E.; Abdel-Hamied, E.; Martinez-Cortes, I.; Liang, Y.; Trevisi, E.; Yoon, I.; et al. Feeding a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product improves udder health and immune response to a Streptococcus uberis mastitis challenge in mid-lactation dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Gao, S.; Xu, T.; Yin, Y. JAK/STAT signaling in diabetic kidney disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1233259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SNP | Chromosome | Location | Mutations in the Former | After the Mutation | Candidate Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP-1 | 3 | 77,727,500 | A | G | gene-CDC14A |

| SNP-2 | 5 | 5,289,808 | T | C | gene-LOC108636124, gene-PHLDA1 |

| SNP-3 | 10 | 57,666,708 | C | G | gene-ZNF609 |

| SNP-4 | 13 | 73,139,883 | C | T | gene-RBPJL |

| SNP-5 | 20 | 39,072,994 | G | A | gene-LOC102191110 |

| SNP-6 | 5 | 27,027,033 | C | T | gene-LOC102177517 |

| SNP-7 | 15 | 37,633,188 | C | A | gene-LOC102183585 |

| SNP-8 | 23 | 19,470,992 | G | A | gene-ZSCAN9 |

| SNP-9 | 25 | 42,365,731 | C | A | gene-ZFAND2A |

| SNP-10 | 27 | 29,255,238 | T | C | gene-F11 |

| Mark | Chr | Position | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14_94113738 | 14 | 94,113,738 | 1.00 × 10−10 |

| 4_112826548 | 4 | 1.13 × 108 | 1.58 × 10−10 |

| 4_112826558 | 4 | 1.13 × 108 | 1.58 × 10−10 |

| 4_112828377 | 4 | 1.13 × 108 | 3.16 × 10−10 |

| 6_96304798 | 6 | 96,304,798 | 4.17 × 10−10 |

| 4_112828332 | 4 | 1.13 × 108 | 4.42 × 10−10 |

| 13_11635958 | 13 | 11,635,958 | 4.50 × 10−10 |

| 13_73078855 | 13 | 73,078,855 | 6.38 × 10−10 |

| 15_35470891 | 15 | 35,470,891 | 2.00 × 10−9 |

| 10_36720798 | 10 | 36,720,798 | 2.40 × 10−9 |

| 4_112824572 | 4 | 1.13 × 108 | 5.77 × 10−9 |

| 4_112690246 | 4 | 1.13 × 108 | 7.56 × 10−9 |

| 25_42375278 | 25 | 42,375,278 | 8.56 × 10−9 |

| 4_112819631 | 4 | 1.13 × 108 | 1.10 × 10−8 |

| 13_73147747 | 13 | 73,147,747 | 1.16 × 10−8 |

| 11_87799604 | 11 | 87,799,604 | 1.30 × 10−8 |

| 25_42365217 | 25 | 42,365,217 | 1.64 × 10−8 |

| 27_16508513 | 27 | 16,508,513 | 1.72 × 10−8 |

| 28_40373888 | 28 | 40,373,888 | 1.74 × 10−8 |

| 1_3266310 | 1 | 3,266,310 | 1.86 × 10−8 |

| 5_92155728 | 5 | 92,155,728 | 1.87 × 10−8 |

| 28_39989356 | 28 | 39,989,356 | 1.92 × 10−8 |

| 25_42467165 | 25 | 42,467,165 | 2.12 × 10−8 |

| 11_41609340 | 11 | 41,609,340 | 2.30 × 10−8 |

| 27_29255284 | 27 | 29,255,284 | 2.31 × 10−8 |

| 4_112824616 | 4 | 1.13 × 108 | 2.34 × 10−8 |

| 25_25701127 | 25 | 25,701,127 | 2.44 × 10−8 |

| 11_90960697 | 11 | 90,960,697 | 2.80 × 10−8 |

| 7_24603319 | 7 | 24,603,319 | 2.90 × 10−8 |

| 7_24613281 | 7 | 24,613,281 | 2.90 × 10−8 |

| 12_81575258 | 12 | 81,575,258 | 3.38 × 10−8 |

| 13_72876834 | 13 | 72,876,834 | 3.70 × 10−8 |

| 16_75562492 | 16 | 75,562,492 | 3.72 × 10−8 |

| 11_42215384 | 11 | 42,215,384 | 3.82 × 10−8 |

| 1_131580172 | 1 | 1.32 × 108 | 3.90 × 10−8 |

| 11_87796475 | 11 | 87,796,475 | 3.93 × 10−8 |

| 6_96305737 | 6 | 96,305,737 | 4.57 × 10−8 |

| 27_16510017 | 27 | 16,510,017 | 4.74 × 10−8 |

| Ontology | GO ID | Description | Gene Ratio (30) | Bg Ratio (13,582) | p Value | Gene ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Component | GO: 0005929 | cilium | 4 | 427 | 0.013822146 | gene-CDC14A; gene-DISC1; gene-DNAH3; gene-PKHD1 |

| Cellular Component | GO: 0042995 | cell projection | 4 | 427 | 0.013822146 | gene-CDC14A; gene-DISC1; gene-DNAH3; gene-PKHD1 |

| Cellular Component | GO: 0120025 | plasma membrane bounded cell projection | 4 | 427 | 0.013822146 | gene-CDC14A; gene-DISC1; gene-DNAH3; gene-PKHD1 |

| Biological Process | GO: 0051301 | cell division | 3 | 263 | 0.02431167 | gene-ACTR3; gene-ANK3; gene-MAP10 |

| KEGG_A _Class | KEGG_B _Class | Pathway | chx (20) | All (8758) | p Value | Pathway ID | Genes | KOs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Information Processing | Signal transduction | NF-kappa B signaling pathway | 4 | 103 | 0.0033965 | ko04064 | gene-TAB2; gene-PLCG2; gene-PRKCQ; gene-CARD11 | K04404+K05859+K18052+K07367 |

| Human Diseases | Cardiovascular disease | Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis | 4 | 143 | 0.010747 | ko05418 | gene-BMP4; gene-PDGFA; gene- SDC4; gene-MGST1 | K04662+K04359+K16338+K00799 |

| Human Diseases | Cancer: overview | Proteoglycans in cancer | 3 | 209 | 0.011318 | ko05205 | gene-SDC4; gene-PLCG2; gene-ANK3 | K16338+K05859+K10380 |

| Human Diseases | Drug resistance: antineoplastic | EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance | 3 | 80 | 0.0123886 | ko01521 | gene-PDGFA; gene-NRG1; gene-PLCG2 | K04359+K05455+K05859 |

| Metabolism | Lipid metabolism | Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 2 | 85 | 0.015792 | ko00140 | gene-LOC102188238; gene-LOC108633246 | K00497+K00699 |

| Organismal Systems | Development and regeneration | Axon guidance | 4 | 179 | 0.0227066 | ko04360 | gene-ROBO1; gene-PLCG2; gene-UNC5D; gene-PLXNA4 | K06753+K05859+K07521+K06820 |

| Environmental Information Processing | Signal transduction | Notch signaling pathway | 2 | 53 | 0.0406895 | ko04330 | gene-RBPJL; gene-ATXN1 | K06053+K23616 |

| Metabolism | Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins | Thiamine metabolism | 1 | 20 | 0.0447426 | ko00730 | gene-NTPCR | K06928 |

| Locus | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| g. 77727500 | Genotype | AA (30) | 0.14 |

| AG (79) | 0.38 | ||

| GG (100) | 0.48 | ||

| Allele | A | 0.33 | |

| G | 0.67 | ||

| He | 0.444 | ||

| PIC | 0.345 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 4.609 | ||

| p | 0.032 | ||

| g. 5289808 | Genotype | TT (86) | 0.41 |

| TC (74) | 0.35 | ||

| CC (49) | 0.24 | ||

| Allele | T | 0.59 | |

| C | 0.41 | ||

| He | 0.484 | ||

| PIC | 0.367 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 15.118 | ||

| p | 0.0001 | ||

| g. 57666708 | Genotype | CC (118) | 0.56 |

| CG (79) | 0.38 | ||

| GG (12) | 0.06 | ||

| Allele | C | 0.75 | |

| G | 0.25 | ||

| He | 0.371 | ||

| PIC | 0.302 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 0.066 | ||

| p | 0.797 | ||

| g. 73139883 | Genotype | CC (98) | 0.47 |

| CT (86) | 0.41 | ||

| TT (25) | 0.12 | ||

| Allele | C | 0.67 | |

| T | 0.33 | ||

| He | 0.439 | ||

| PIC | 0.343 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 0.821 | ||

| p | 0.365 | ||

| g. 39072994 | Genotype | GG (191) | 0.91 |

| GA (17) | 0.08 | ||

| AA (1) | 0.01 | ||

| Allele | G | 0.95 | |

| A | 0.05 | ||

| He | 0.087 | ||

| PIC | 0.083 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 0.821 | ||

| p | 0.365 | ||

| g. 27027033 | Genotype | CC (104) | 0.52 |

| CT (80) | 0.40 | ||

| TT (15) | 0.08 | ||

| Allele | C | 0.72 | |

| T | 0.28 | ||

| He | 0.400 | ||

| PIC | 0.320 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 0.005 | ||

| p | 0.943 | ||

| g. 37633188 | Genotype | CC (42) | 0.21 |

| CA (91) | 0.455 | ||

| AA (67) | 0.335 | ||

| Allele | C | 0.44 | |

| A | 0.56 | ||

| He | 0.492 | ||

| PIC | 0.371 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 1.142 | ||

| p | 0.285 | ||

| g. 19470992 | Genotype | GG (142) | 0.71 |

| GA (53) | 0.265 | ||

| AA (5) | 0.025 | ||

| Allele | G | 0.84 | |

| A | 0.16 | ||

| He | 0.265 | ||

| PIC | 0.230 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 0.0004 | ||

| p | 0.984 | ||

| g. 42365731 | Genotype | CC (162) | 0.82 |

| CA (34) | 0.17 | ||

| AA (1) | 0.01 | ||

| Allele | C | 0.91 | |

| A | 0.09 | ||

| He | 0.166 | ||

| PIC | 0.152 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 0.306 | ||

| p | 0.580 | ||

| g. 29255238 | Genotype | TT (102) | 0.51 |

| TC (78) | 0.39 | ||

| CC (20) | 0.10 | ||

| Allele | T | 0.705 | |

| C | 0.295 | ||

| He | 0.416 | ||

| PIC | 0.329 | ||

| Equilibrium χ2 test | 0.778 | ||

| p | 0.378 | ||

| Site | Genotype | Milk Yield (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| g. 77727500 | AA (30) | 3.98 a ± 0.20 |

| AG (79) | 3.17 b ± 0.12 | |

| GG (100) | 3.28 ab ± 0.11 | |

| g. 5289808 | TT (86) | 3.40 ± 0.12 |

| TC (74) | 3.45 ± 0.13 | |

| CC (49) | 3.03 ± 0.16 | |

| g. 57666708 | CC (118) | 3.17 ± 0.10 |

| CG (79) | 3.52 ± 0.12 | |

| GG (12) | 3.83 ± 0.31 | |

| g. 73139883 | CC (98) | 3.06 b ± 0.10 |

| CT (86) | 3.37 b ± 0.11 | |

| TT (25) | 4.30 a ± 0.20 | |

| g. 39072994 | GG (191) | 3.26 ± 0.07 |

| GA (17) | 4.24 ± 0.46 | |

| AA (1) | 2.7 | |

| g. 27027033 | CC (104) | 3.18 b ± 0.10 |

| CT (80) | 3.25 b ± 0.11 | |

| TT (15) | 4.69 a ± 0.25 | |

| g. 37633188 | CC (42) | 2.98 b ± 0.16 |

| CA (91) | 3.14 b ± 0.11 | |

| AA (67) | 3.83 a ± 0.13 | |

| g. 19470992 | GG (142) | 3.09 b ± 0.09 |

| GA (53) | 3.91 a ± 0.14 | |

| AA (5) | 4.01 a ± 0.46 | |

| g. 42365731 | CC (162) | 3.21 b ± 0.91 |

| CA (34) | 3.92 a ± 1.60 | |

| AA (1) | 3.3 ab | |

| g. 29255238 | TT (102) | 3.03 c ± 0.10 |

| TC (78) | 3.42 b ± 0.11 | |

| CC (20) | 4.59 a ± 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F.; He, Y.; Yan, H.; Bu, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Li, D.; Cao, B.; An, X. GWAS Reveals Key Candidate Genes Associated with Milk-Production in Saanen Goats. Animals 2025, 15, 3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223282

Li F, He Y, Yan H, Bu J, Wang Z, Xu X, Li D, Cao B, An X. GWAS Reveals Key Candidate Genes Associated with Milk-Production in Saanen Goats. Animals. 2025; 15(22):3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223282

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fu, Yonglong He, Hanbing Yan, Jiaqi Bu, Zhanhang Wang, Xiaolong Xu, Danni Li, Binyun Cao, and Xiaopeng An. 2025. "GWAS Reveals Key Candidate Genes Associated with Milk-Production in Saanen Goats" Animals 15, no. 22: 3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223282

APA StyleLi, F., He, Y., Yan, H., Bu, J., Wang, Z., Xu, X., Li, D., Cao, B., & An, X. (2025). GWAS Reveals Key Candidate Genes Associated with Milk-Production in Saanen Goats. Animals, 15(22), 3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223282