Structure-Aware Multi-Animal Pose Estimation for Space Model Organism Behavior Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a single-stage two-hop regression framework for multi-animal pose estimation that avoids dependence on object detection and post-processing, achieving both high efficiency and precision.

- We design anatomical prior-based pose grouping representations tailored to C. elegans, zebrafish, and Drosophila, enabling structurally aware modeling across species.

- We develop a Multi-scale Feature Sampling Module to enhance spatial feature representation and adaptability across animals of different body scales.

- We introduce a Structure-guided Learning Module that captures inter-keypoint structural relationships, significantly improving robustness under occlusion and overlap conditions.

- We validate our method on a C. elegans dataset collected from actual missions aboard the China Space Station, and conduct extended experiments on zebrafish and Drosophila datasets to demonstrate generalizability and state-of-the-art performance.

2. Related Work

2.1. Top–Down Methods

2.2. Bottom–up Methods

2.3. Single-Stage Regression Methods

2.4. Animal-Specific Pose Estimation Studies

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Architecture

- Center Heatmap Branch: This predicts the heatmap of instance centers;

- Two-Hop Regression Branch: This predicts the offset vectors from centers to keypoints through intermediate part points;

- Keypoint Heatmap Branch: This assists geometric prior learning of keypoint distributions (used only during training).

3.2. Pose-Grouping Representation Method

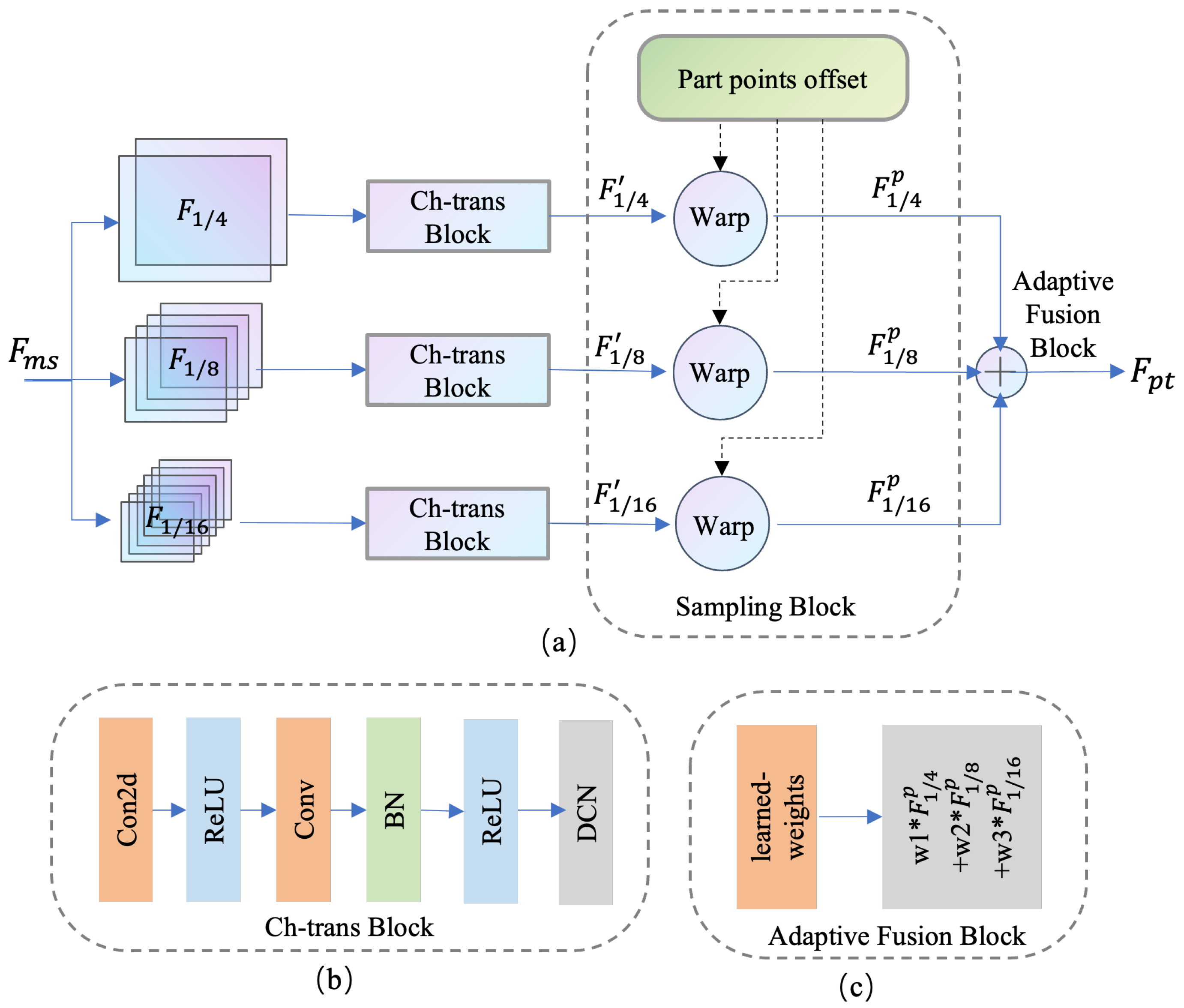

3.3. Multi-Scale Feature-Sampling Module

3.4. Structure-Guided Learning Module

3.5. Loss Function

4. Materials

4.1. Datesets

4.2. Implementation Details and Metrics

5. Experiments

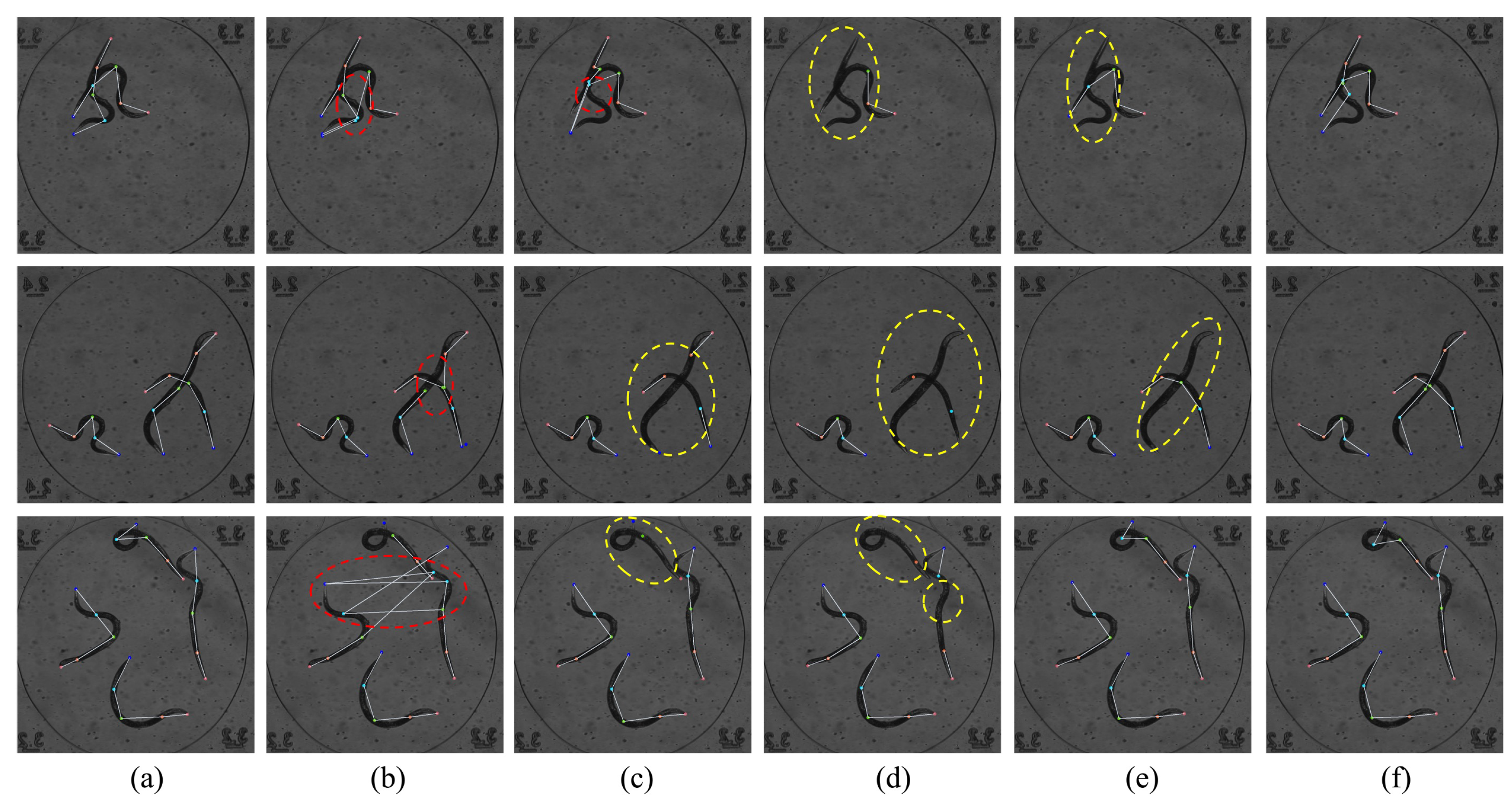

5.1. C. elegans Dataset

5.2. Zebrafish Dataset

5.3. Drosophila Dataset

6. Ablation Study

6.1. Ablation Study on the Multi-Scale Feature Sampling Module (MFS)

6.2. Ablation Study on Structure-Guided Learning Module (SGL)

6.3. Ablation Experiments on Different Modules Across Three Datasets

6.4. Effect of Removing Keypoint Heatmap Branch During Inference

6.5. Efficiency Comparison Across Different Frameworks

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herranz, R.; Anken, R.; Boonstra, J.; Braun, M.; Christianen, P.C.M.; de Geest, M.; Hauslage, J.; Hilbig, R.; Hill, R.J.A.; Lebert, M.; et al. Ground-Based Facilities for Simulation of Microgravity: Organism-Specific Recommendations for Their Use, and Recommended Terminology. Astrobiology 2013, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silveira, W.A.; Fazelinia, H.; Rosenthal, S.B.; Laiakis, E.C.; Kim, M.S.; Meydan, C.; Kidane, Y.; Rathi, K.S.; Smith, S.M.; Stear, B.; et al. Comprehensive Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals Mitochondrial Stress as a Central Biological Hub for Spaceflight Impact. Cell 2020, 183, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duporge, I.; Pereira, T.; de Obeso, S.C.; Ross, J.G.B.; Lee, S.J.; Hindle, A.G. The Utility of Animal Models to Inform the Next Generation of Human Space Exploration. NPJ Microgravity 2025, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, L.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y. Integrated Spaceflight Transcriptomic Analyses and Simulated Space Experiments Reveal Key Molecular Features and Functional Changes Driven by Space Stressors in Space-Flown C. Elegans. Life Sci. Space Res. 2025, 44, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathis, A.; Mamidanna, P.; Cury, K.M.; Abe, T.; Murthy, V.N.; Mathis, M.W.; Bethge, M. DeepLabCut: Markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.D.; Aldarondo, D.E.; Willmore, L.; Kislin, M.; Wang, S.S.-H.; Murthy, M.; Shaevitz, J.W. Fast animal pose estimation using deep neural networks. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, P.; Shang, H.; Qu, L.; Lei, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.; He, R.; Long, M.; et al. Recent Review and Prospect of Space Life Science in China for 40 Years (in Chinese). Chin. J. Space Sci. 2021, 41, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.D.; Tabris, N.; Matsliah, A.; Turner, D.M.; Li, J.; Ravindranath, S.; Papadoyannis, E.S.; Normand, E.; Deutsch, D.S.; Wang, Z.Y.; et al. SLEAP: A Deep Learning System for Multi-Animal Pose Tracking. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zheng, H.; Yang, J.; Deng, H.; Zhang, T. Study on poultry pose estimation based on multi-parts detection. Animals 2022, 12, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, M.W.; Mathis, A. Deep learning tools for the measurement of animal behavior in neuroscience. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, J.F.; Hsu, A.I.; Schwarz, M.K.; Yttri, E.A. A-SOiD, an active-learning platform for expert-guided, data-efficient discovery of behavior. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, P.C.; Eisenreich, B.R.; Yoo, S.B.M.; Hayden, B.Y.; Park, H.S.; Zimmermann, J. Automated markerless pose estimation in freely moving macaques with OpenMonkeyStudio. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graving, J.M.; Chae, D.; Naik, H.; Li, L.; Koger, B.; Costelloe, B.R.; Couzin, I.D. DeepPoseKit, a software toolkit for fast and robust animal pose estimation using deep learning. Elife 2019, 8, e47994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segalin, C.; Williams, J.; Karigo, T.; Hui, M.; Zelikowsky, M.; Sun, J.J.; Perona, P.; Anderson, D.J.; Kennedy, A. The Mouse Action Recognition System (MARS) software pipeline for automated analysis of social behaviors in mice. Elife 2021, 10, e63720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauer, J.; Zhou, M.; Ye, S.; Menegas, W.; Schneider, S.; Nath, T.; Rahman, M.M.; Di Santo, V.; Soberanes, D.; Feng, G.; et al. Multi-animal pose estimation, identification and tracking with DeepLabCut. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testard, C.; Tremblay, S.; Parodi, F.; DiTullio, R.W.; Acevedo-Ithier, A.; Gardiner, K.L.; Kording, K.; Platt, M.L. Neural signatures of natural behaviour in socializing macaques. Nature 2024, 628, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anken, R.; Hilbig, R. Swimming behaviour of the upside-down swimming catfish (Synodontis nigriventris) at high-quality microgravity–A drop-tower experiment. Adv. Space Res. 2009, 44, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronca, A.E.; Moyer, E.L.; Talyansky, Y.; Lowe, M.; Padmanabhan, S.; Choi, S.; Gong, C.; Cadena, S.M.; Stodieck, L.; Globus, R.K. Behavior of mice aboard the International Space Station. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzzadeh, M.S.; Nguyen, A.; Kosmala, M.; Swanson, A.; Palmer, M.S.; Packer, C.; Clune, J. Automatically identifying, counting, and describing wild animals in camera-trap images with deep learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5716–E5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, M.; Wolf, N.; Rosenberg, B.; Harris, B.P.; Mathis, A. Perspectives on individual animal identification from biology and computer vision. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 900–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Guan, Z.; Tao, D. AP-10K: A benchmark for animal pose estimation in the wild. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.; Jin, Q.; Sturman, O.; von Ziegler, L.; Kollmorgen, S.; von der Behrens, W.; Mante, V.; Bohacek, J.; Yanik, M.F. Deep-learning-based identification, tracking, pose estimation and behaviour classification of interacting primates and mice in complex environments. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.S.; Li, J.; Tang, H.; Xu, C.; Zhu, H.; Xiu, Y.; Li, Y.L.; Lu, C. AlphaPose: Whole-body regional multi-person pose estimation and tracking in real-time. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 7157–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.E.; Ramakrishna, V.; Kanade, T.; Sheikh, Y. Convolutional pose machines. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 4724–4732. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, A.; Yang, K.; Deng, J. Stacked hourglass networks for human pose estimation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Xiao, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, J. Deep high-resolution representation learning for human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 5693–5703. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Feng, R.; Wu, S.; Ji, S.; Yang, B.; Wang, X. Deep dual consecutive network for human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 525–534. [Google Scholar]

- Bertasius, G.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Tran, D.; Shi, J.; Torresani, L. Learning temporal pose estimation from sparsely-labeled videos. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.S.; Xie, S.; Tai, Y.W.; Lu, C. RMPE: Regional multi-person pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2334–2343. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.E.; Sheikh, Y. Realtime multi-person 2D pose estimation using part affinity fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7291–7299. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, A.; Huang, Z.; Deng, J. Associative embedding: End-to-end learning for joint detection and grouping. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Liu, W.; Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Qian, C.; Ouyang, W.; Luo, P. Differentiable hierarchical graph grouping for multi-person pose estimation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 718–734. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiss, S.; Bertoni, L.; Alahi, A. PifPaf: Composite fields for human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 11977–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Lin, S. Point-set anchors for object detection, instance segmentation and pose estimation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Tan, T.; Zhou, E. Rethinking the heatmap regression for bottom-up human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13264–13273. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Z.; Sun, K.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Bottom-up human pose estimation via disentangled keypoint regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 14676–14686. [Google Scholar]

- Pishchulin, L.; Insafutdinov, E.; Tang, S.; Andres, B.; Andriluka, M.; Gehler, P.V.; Schiele, B. DeepCut: Joint subset partition and labeling for multi person pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 4929–4937. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, D.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; He, M. AdaptivePose: Human parts as adaptive points. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 2813–2821. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, S. Contextual instance decoupling for robust multi-person pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11060–11068. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, X.L.; Ong, K.E.; Zheng, Q.; Ni, Y.; Yeo, S.Y.; Liu, J. Animal kingdom: A large and diverse dataset for animal behavior understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 19023–19034. [Google Scholar]

- Robie, A.A.; Taylor, A.L.; Schretter, C.E.; Kabra, M.; Branson, K. The fly disco: Hardware and software for optogenetics and fine-grained fly behavior analysis. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azabou, M.; Mendelson, M.; Ahad, N.; Sorokin, M.; Thakoor, S.; Urzay, C.; Dyer, E. Relax, it doesn’t matter how you get there: A new self-supervised approach for multi-timescale behavior analysis. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 28491–28509. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, R.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, R.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Pose estimation and tracking dataset for multi-animal behavior analysis on the China Space Station. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.-J.; Li, K.; Li, F.-F. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Input Size | Backbone | AP | AR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.657 | 0.951 | 0.723 | 0.733 |

| DEKR | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.633 | 0.889 | 0.717 | 0.691 |

| CID | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.703 | 0.947 | 0.796 | 0.763 |

| AdaptivePose | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.685 | 0.936 | 0.768 | 0.757 |

| Ours | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.728 | 0.970 | 0.807 | 0.793 |

| Method | Input Size | Backbone | AP | AP50 | AP75 | AR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.562 | 0.770 | 0.617 | 0.438 |

| DEKR | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.591 | 0.780 | 0.655 | 0.421 |

| CID | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.575 | 0.765 | 0.665 | 0.637 |

| AdaptivePose | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.577 | 0.788 | 0.632 | 0.624 |

| Ours | 512 × 512 | HRNet-W32 | 0.621 | 0.804 | 0.679 | 0.664 |

| Method | Input Size | Backbone | AP | AR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | 640 × 640 | HRNet-W32 | 0.469 | 0.776 | 0.529 | 0.536 |

| DEKR | 640 × 640 | HRNet-W32 | 0.583 | 0.906 | 0.667 | 0.633 |

| CID | 640 × 640 | HRNet-W32 | 0.562 | 0.853 | 0.655 | 0.623 |

| Adaptive Pose | 640 × 640 | HRNet-W32 | 0.620 | 0.909 | 0.677 | 0.688 |

| Ours | 640 × 640 | HRNet-W32 | 0.671 | 0.951 | 0.740 | 0.732 |

| Ch_trans | Fusion | Features | AP | AR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT1 | con_cat | 0.694 | 0.948 | 0.772 | 0.756 | |

| CT1 | A_add | 0.705 | 0.953 | 0.789 | 0.770 | |

| CT2 | A_add | 0.708 | 0.949 | 0.786 | 0.774 | |

| CT2 | A_add | 0.717 | 0.965 | 0.811 | 0.783 | |

| CT2 | A_add | 0.717 | 0.967 | 0.792 | 0.783 | |

| CT2 | A_add | 0.691 | 0.945 | 0.769 | 0.761 | |

| CT2 | A_add | 0.713 | 0.964 | 0.808 | 0.780 | |

| CT2 | A_add | 0.711 | 0.975 | 0.795 | 0.785 |

| Type Embed | Dim_Feedforward | Num_Layers | AP | AR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disabled | 512 | 1 | 0.706 | 0.955 | 0.792 | 0.777 |

| Enabled | 512 | 1 | 0.718 | 0.969 | 0.817 | 0.788 |

| Enabled | 1024 | 1 | 0.711 | 0.945 | 0.678 | 0.755 |

| Enabled | 512 | 2 | 0.714 | 0.964 | 0.806 | 0.782 |

| Dataset | Method | Input | GFLOPs | Params/M | AP | AR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. elegans | Baseline | 512 | 52.24 | 29.4 | 0.685 | 0.936 | 0.768 | 0.757 |

| +MFS | 512 | 53.94 | 31.43 | 0.717 | 0.967 | 0.792 | 0.783 | |

| +SGL | 512 | 57.65 | 29.48 | 0.718 | 0.969 | 0.817 | 0.788 | |

| +MFS&SGL | 512 | 59.35 | 31.50 | 0.728 | 0.970 | 0.807 | 0.793 | |

| Zebrafish | Baseline | 512 | 52.25 | 29.4 | 0.577 | 0.788 | 0.632 | 0.624 |

| +MFS | 512 | 53.95 | 31.43 | 0.609 | 0.796 | 0.648 | 0.655 | |

| +SGL | 512 | 57.66 | 29.48 | 0.607 | 0.792 | 0.659 | 0.650 | |

| +MFS&SGL | 512 | 59.36 | 31.50 | 0.621 | 0.804 | 0.679 | 0.664 | |

| Drosophila | Baseline | 640 | 58.44 | 29.93 | 0.620 | 0.909 | 0.677 | 0.688 |

| +MFS | 640 | 59.64 | 31.94 | 0.642 | 0.921 | 0.719 | 0.704 | |

| +SGL | 640 | 68.18 | 30.01 | 0.666 | 0.946 | 0.757 | 0.728 | |

| +MFS&SGL | 640 | 69.88 | 32.03 | 0.671 | 0.951 | 0.740 | 0.732 |

| Method | AP (%) | AR (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ours (with heatmap branch during inference) | 72.91 | 79.42 |

| Ours (heatmap branch removed during inference) | 72.83 | 79.30 |

| Dataset | Method Type | Method | Input Size | AP | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. elegans | Top–Down | HRNet | 256 × 192 | 0.701 | 2.98 |

| Bottom–Up | AE | 512 × 512 | 0.657 | 3.70 | |

| One-Stage | Ours | 512 × 512 | 0.728 | 12.66 | |

| Zebrafish | Top-Down | HRNet | 256 × 192 | 0.537 | 2.27 |

| Bottom-Up | AE | 512 × 512 | 0.562 | 2.76 | |

| One-Stage | Ours | 512 × 512 | 0.621 | 11.24 | |

| Drosophila | Top-Down | HRNet | 256 × 192 | 0.608 | 0.72 |

| Bottom-Up | AE | 640 × 640 | 0.399 | 1.02 | |

| One-Stage | Ours | 640 × 640 | 0.671 | 6.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, K.; Li, S.; Lv, Y.; Yang, R.; Li, X. Structure-Aware Multi-Animal Pose Estimation for Space Model Organism Behavior Analysis. Animals 2025, 15, 3139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213139

Liu K, Li S, Lv Y, Yang R, Li X. Structure-Aware Multi-Animal Pose Estimation for Space Model Organism Behavior Analysis. Animals. 2025; 15(21):3139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213139

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Kang, Shengyang Li, Yixuan Lv, Rong Yang, and Xuzhi Li. 2025. "Structure-Aware Multi-Animal Pose Estimation for Space Model Organism Behavior Analysis" Animals 15, no. 21: 3139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213139

APA StyleLiu, K., Li, S., Lv, Y., Yang, R., & Li, X. (2025). Structure-Aware Multi-Animal Pose Estimation for Space Model Organism Behavior Analysis. Animals, 15(21), 3139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213139