Tracking the Migratory Life History of Brown Croaker (Miichthys miiuy) Through Otolith Microchemistry in the East China Sea

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Develop the otolith magnesium chemical clock in combination with otolith microstructure as a temporal reference to support the reconstruction of migratory life history.

- (2)

- Use typical tracer elements (Sr:Ca and Ba:Ca) in otolith cores to identify the water chemistry information of natal sources and establish Sr:Ba thresholds from estuary to offshore.

- (3)

- Reconstruct the migratory life history of M. miiuy by combining information from the magnesium chemical clock and Sr:Ba of otoliths.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Collection

2.2. Otolith Microchemistry Analysis

2.3. Otolith Age Reading

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Otolith Mg:Ca Chemical Clock

3.2. Natal Sources and Migratory Life History

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility of Using Mg:Ca as a Chemical Clock for M. miiuy

4.2. Natal Sources

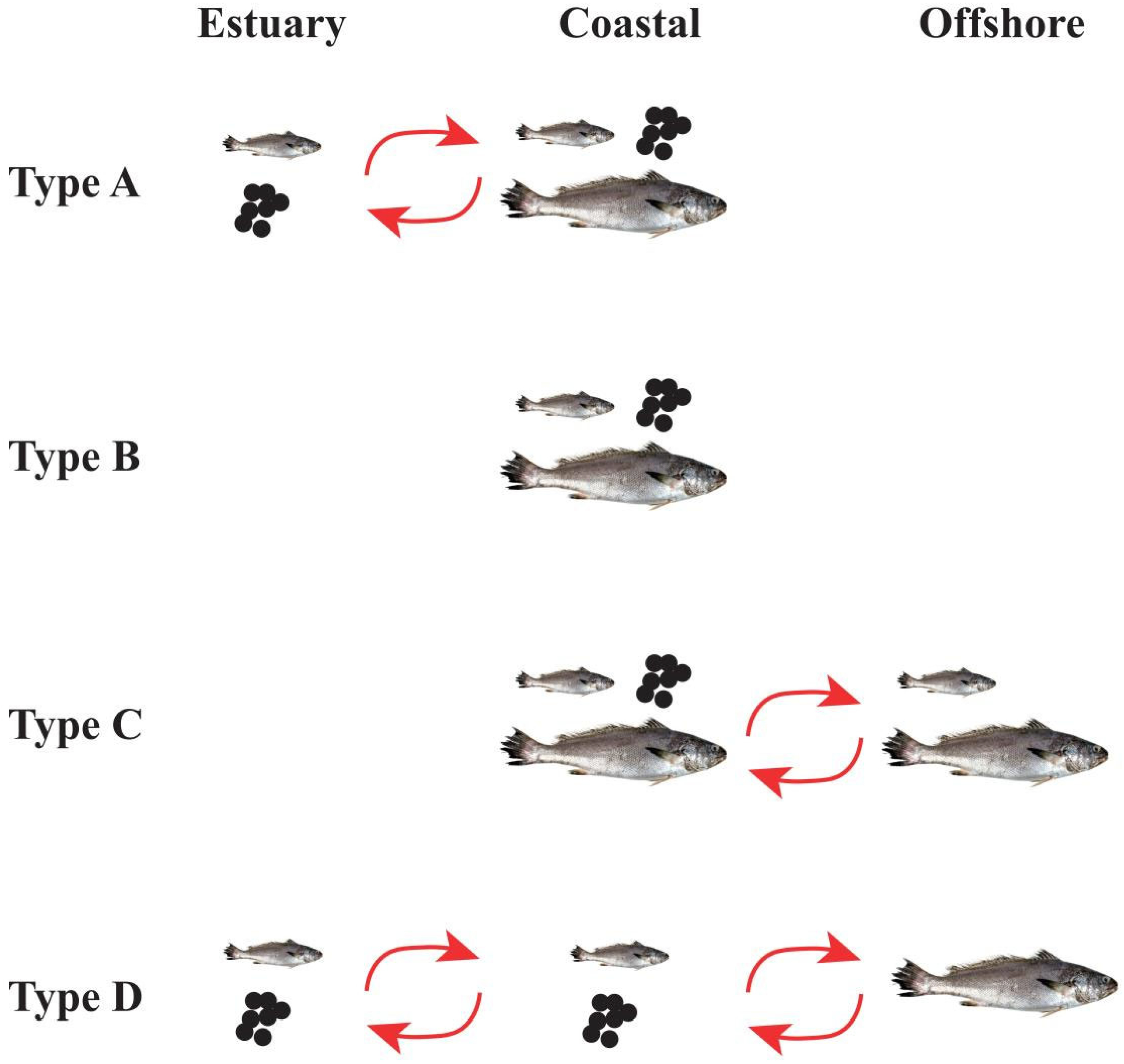

4.3. Diversity of Migratory Life History

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beck, M.W.; Heck, K.L.; Able, K.W.; Childers, D.L.; Eggleston, D.B.; Gillanders, B.M.; Halpern, B.; Hays, C.G.; Hoshino, K.; Minello, T.J.; et al. The identification, conservation, and management of estuarine and marine nurseries for fish and invertebrates: A better understanding of the habitats that serve as nurseries for marine species and the factors that create site-specific variability in nursery quality will improve conservation and management of these areas. Bioscience 2001, 51, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A.; Cowley, P.; Næsje, T.; Bennett, R. Habitat connectivity and intra-population structure of an estuary-dependent fishery species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015, 537, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J.; Régnier, T.; Gibb, F.M.; Augley, J.; Devalla, S. Assessing the role of ontogenetic movement in maintaining population structure in fish using otolith microchemistry. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 7907–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Z.; Wang, W.X. Diversity of life history and population connectivity of threadfin fish Eleutheronema tetradactylum along the coastal waters of Southern China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, K.; Arai, T. Facultative catadromy of the eel Anguilla japonica between freshwater and seawater habitats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 220, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A.M.; Smith, S.M.; Booth, D.J.; Stewart, J. Partial migration of grey mullet (Mugil cephalus) on Australia’s east coast revealed by otolith chemistry. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 119, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.L.; Chapman, M.R. Implications of fish home range size and relocation for marine reserve function. Environ. Biol. Fishes 1999, 55, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.W.; Yeakel, J.D.; Peard, D.; Lough, J.; Beere, M. Life-history diversity and its importance to population stability and persistence of a migratory fish: Steelhead in two large North American watersheds. J. Anim. Ecol. 2014, 83, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Lou, B.; Yuan, J. Study on the early development in larvae and juveniles of Miichthys miiuy. J. Shanghai. Fish. Univ. 2005, 14, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.D.; Li, S.F. The Main Economic Species in East China Sea Three Channels and a Protection Zone Atlas; Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.Y.; Baeck, G.W.; Jung, J.H.; Choi, H.; Kim, C.; Koo, M.S.; Park, J.H. Spatiotemporal distribution and reproductive biology of the brown croaker (Miichthys miiuy) in the southwestern waters of Korea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1416771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.W.; Jiang, Y.S.; Gao, X.D.; Yang, L.L.; Liu, Z.L.; Cheng, J.H. Spatiotemporal distribution of Lophius liuon in the souther Yellow Sea and Fast China Sea. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 34, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Nin, B.; Geffen, A.J.; Pérez-Mayol, S.; Palmer, M.; González-Quirós, R.; Grau, A. Seasonal and ontogenic migrations of meagre (Argyrosomus regius) determined by otolith geochemical signatures. Fish. Res. 2012, 127, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Meadows, N.M.; Stewart, J.; Booth, D.J.; Fowler, A.M. Movement patterns of an iconic recreational fish species, mulloway (Argyrosomus japonicus), revealed by cooperative citizen-science tagging programs in coastal eastern Australia. Fish. Res. 2022, 247, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.C.; Rogers, P.J.; Wolf, Y.; Madonna, A.; Holman, D.; Ferguson, G.J.; Hutchinson, W.; Loisier, A.; Sortino, D.; Sumner, M.; et al. Dispersal of an exploited demersal fish species (Argyrosomus japonicus, Sciaenidae) inferred from satellite telemetry. Mar. Biol. 2019, 166, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.D.; Babcock, R.C.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Crook, D.A. Where technology meets ecology: Acoustic telemetry in contemporary Australian aquatic research and management. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2017, 68, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.; Taylor, M.D.; Barnes, T.C.; Johnson, D.D.; Gillanders, B.M. Habitat transitions by a large coastal sciaenid across life history stages, resolved using otolith chemistry. Mar. Environ. Res. 2022, 176, 105614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E. Otolith science entering the 21st century. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2005, 56, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Iglio, C.; Famulari, S.; Albano, M.; Carnevale, A.; Di Fresco, D.; Costanzo, M.; Lanteri, G.; Spanò, N.; Savoca, S.; Capillo, G. Intraspecific variability of the saccular and utricular otoliths of the hatchetfish Argyropelecus hemigymnus (Cocco, 1829) from the Strait of Messina (Central Mediterranean Sea). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E.; Casselman, J.M. Stock Discrimination Using Otolith Shape Analysis. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1993, 50, 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Mirbach, T.; Ladich, F.; Plath, M.; Hess, M. Enigmatic ear stones: What we know about the functional role and evolution of fish otoliths. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 457–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, B.M.; Pupo, D.V.; Volpedo, A.V.; Pisonero, J.; Méndez, A.; Avigliano, E. Spatial environmental variability of natural markers and habitat use of Cathorops spixii in a neotropical estuary from otolith chemistry. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2020, 100, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.; Campana, S.E. Regulation of calcium and strontium deposition on the otoliths of juvenile tilapia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Physiol. 1996, 115, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, B.D.; Thorrold, S.R. Water, not food, contributes the majority of strontium and barium deposited in the otoliths of a marine fish. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 311, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, T.P.; Albuquerque, C.Q.; Santos, R.S.; Saint’pierre, T.D.; Araújo, F.G. Leave forever or return home? The case of the whitemouth croaker Micropogonias furnieri in coastal systems of southeastern Brazil indicated by otolith microchemistry. Mar. Environ. Res. 2019, 144, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.L.; Gillanders, B.M.; Barnes, T.C.; Johnson, D.D.; Taylor, M.D. Inter-estuarine variation in otolith chemistry in a large coastal predator: A viable tool for identifying coastal nurseries? Estuaries Coasts 2021, 44, 1132–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, M.; Cappo, M.; Aumend, J.; Müller, W. Tracing the life history of individual barramundi using laser ablation MC-ICP-MS Sr-isotopic and Sr/Ba ratios in otoliths. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2005, 56, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Z.; Wang, W. Trace elemental and stable isotopic signatures to reconstruct the large-scale environmental connectivity of fish populations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2024, 730, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturrock, A.M.; Trueman, C.N.; Milton, J.A.; Waring, C.P.; Cooper, M.J.; Hunter, E. Physiological influences can outweigh environmental signals in otolith microchemistry research. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 500, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limburg, K.E.; Wuenschel, M.J.; Hüssy, K.; Heimbrand, Y.; Samson, M. Making the Otolith Magnesium Chemical Calendar-Clock Tick: Plausible Mechanism and Empirical Evidence. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2018, 26, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, R.; Basilone, G.; Traina, S.; Saborido-Rey, F.; Mazzola, S. Validation of macroscopic maturity stages according to microscopic histological examination for European anchovy. Mar. Ecol. 2009, 30, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.J.; Jessop, B.M.; Weyl, O.L.F.; Iizuka, Y.; Lin, S.H.; Tzeng, W.-N. Migratory history of African longfinned eel Anguilla mossambica from Maningory River, Madagascar: Discovery of a unique pattern in otolith Sr:Ca ratios. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2015, 98, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.E. Accuracy, precision and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. J. Fish Biol. 2001, 59, 197–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbrand, Y.; Limburg, K.E.; Hüssy, K.; Casini, M.; Sjöberg, R.; Bratt, A.P.; Levinsky, S.; Karpushevskaia, A.; Radtke, K. Seeking the true time: Exploring otolith chemistry as an age-determination tool. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikas, D. Mass spectrometry-based evaluation of the Bland-Altman approach: Review, discussion, and proposal. Molecules 2023, 28, 4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1986, 327, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Ren, Q.Q.; Jiang, T.; Jiang, C.R.; Fang, L.-P.; Zhang, M.Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, M. Otolith microchemistry reveals various habitat uses and life histories of Chinese gizzard shad Clupanodon thrissa in the Min River and the estuary, Fujian Province, China. Fish. Res. 2023, 264, 106723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, N.; Lizé, A.; Tabouret, H.; Gérard, C.; Bareille, G.; Acou, A.; Carpentier, A.; Trancart, T.; Virag, L.S.; Robin, E.; et al. A multi-approach study to reveal eel life-history traits in an obstructed catchment before dam removal. Hydrobiologia 2022, 849, 1885–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liu, J.; Cao, L.; Dou, S. Emperature and salinity effects on strontium and barium incorporation into otoliths of flounder Paralichthys olivaceus at early life stages. Fish. Res. 2021, 239, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Barnett, A.; Bradley, M.; Abrantes, K.; Sheaves, M. Contrasting seascape use by a coastal fish assemblage: A multi-methods approach. Estuaries Coasts 2019, 42, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patin, R.; Etienne, M.-P.; Lebarbier, E.; Chamaillé-Jammes, S.; Benhamou, S. Identifying stationary phases in multivariate time series for highlighting behavioural modes and home range settlements. J. Anim. Ecol. 2019, 89, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patin, R.; Etienne, M.-P.; Lebarbier, E.; Benhamou, S. segclust2d, Version 0.2.0. Software for Bivariate Segmentation and Clustering. The R Project for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019.

- Bath Martin, G.; Thorrold, S. Temperature and salinity effects on magnesium, manganese, and barium incorporation in otoliths of larval and early juvenile spot Leiostomus xanthurus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 293, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturrock, A.M.; Hunter, E.; Milton, J.A.; Eimf; Johnson, R.C.; Waring, C.P.; Trueman, C.N. Quantifying physiological influences on otolith microchemistry. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammer, G.L.; Morrongiello, J.R.; Izzo, C.; Hawthorne, P.J.; Middleton, J.F.; Gillanders, B.M. Coupling biogeochemical tracers with fish growth reveals physiological and environmental controls on otolith chemistry. Ecol. Monogr. 2017, 87, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.R. 10-Environmental factors and growth. In Fish Physiology. Bioenergetics and Growth; Hoar, W.S., Randall, D.J., Brett, J.R., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume VIII, pp. 599–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont-Prinet, A.; Vagner, M.; Chabot, D.; Audet, C. Impact of hypoxia on the metabolism of Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2013, 70, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Maes, J.; Ollevier, F. A bioenergetics model for juvenile flounder Platichthys flesus. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2006, 22, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.R.; Powers, S.P. Elemental Concentrations of Water and Otoliths as Salinity Proxies in a Northern Gulf of Mexico Estuary. Estuaries Coasts 2020, 43, 843–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Li, F.; Dominech, S.; Wen, X.; Yang, S. Heavy metals of surface sediments in the Changjiang (Yangtze River) Estuary: Distribution, speciation and environmental risks. J. Geochem. Explor. 2018, 198, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, X.; Qiao, F.; Xia, C.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, Y. Upwelling off Yangtze River estuary in summer. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2006, 111, C11S08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, X.H. Progress on upwelling studies in the China seas. Rev. Geophys. 2016, 54, 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Xiong, Y.; Jiang, T.; Yang, J.; Zhong, X.; Tang, J.; Kang, Z. Evaluation of Spawning- and Natal-Site Fidelity of Larimichthys polyactis in the Southern Yellow Sea Using Otolith Microchemistry. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 8, 820492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, X.; Li, S. Functional connectivity in the Yangtze Estuary habitats for an “estuarine opportunist” fish: An otolith chemistry approach for small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis). Fish. Sci. 2024, 90, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Liu, H.B.; Jiang, T.; Liu, P.T.; Tang, J.H.; Zhong, X.M.; Yang, J.; Wu, L.; Gao, Y.S. Investigation on otolith microchemistry of wild Pampus argenteus and Miichthys miiuy in the southern Yellow Sea, China. Acta. Oceanol. Sin. 2015, 37, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheaves, M.; Baker, R.; Nagelkerken, I.; Connolly, R.M. True value of estuarine and coastal nurseries for fish: Incorporating complexity and dynamics. Estuaries Coast 2015, 38, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, A.K. Ichthyofaunal assemblages in estuaries: A South African case study. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 1999, 9, 151–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.H.; Zhang, S.Z.; Lu, L.Y.; Lin, K.; Lyu, S.L.; Zeng, J.W.; Chen, H.G.; Wang, X.F. Population characteristics of Collichthys lucidus in the pearl river estuary during 2017 and 2020. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 33, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wu, K.; Wu, L. Influence of the physical environment on the migration and distribution of Nibea albiflora in the Yellow Sea. J. Ocean Univ. China 2017, 16, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secor, D.H. Migration Ecology of Marine Fishes; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016; pp. 609–610. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, L.A.; Cadrin, S.X.; Secor, D.H. The role of spatial dynamics in the stability, resilience, and productivity of an estuarine fish population. Ecol. Appl. 2010, 20, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsdon, T.; Gillanders, B. Relationship between water and otolith elemental concentrations in juvenile black bream Acanthopagrus butcheri. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003, 260, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Tang, R.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. Seasonal variability and dynamics of coastal sea surface temperature fronts in the East China Sea. Ocean Dyn. 2021, 71, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.M.; Gallagher, C.P.; Tierney, K.B.; Howland, K.L. Freshwater early life growth influences partial migration in populations of Dolly Varden (Salvelinus malma malma). Polar Biol. 2021, 44, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Jin, Y.; Ling, J.Z.; Liu, Z.L.; Cheng, J.H. Shrimp community structure and influence of environmental variables in the East China Sea and Yellow Sea in spring. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 34, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.J.; Tang, X.Y.; Yan, X.J.; Song, W.H.; Zhou, Y.D.; Zhang, H.L.; Jiang, R.J.; Yang, J.; Jiang, T. Speculation of migration routes of Larimichthys crocea in the East China Sea based on otolith microchemistry. Haiyang Xuebao 2023, 45, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Jiang, R.; Cui, M.; Yin, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y. Study on the habitat suitability of Miichthys miiuy along the coast of Zhejiang. J. Fish. Sci. China 2025, 32, 960–969. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Zheng, A.; Jin, M.; Huang, S.; Zhao, L.; Tang, S.; Mkulo, E.M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Effects of salinity on growth, survival, tissue structure, osmoregulation, metabolism, and antioxidant capacity of Eleutheronema tetradactylum (Shaw, 1804). Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1553114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | Numbers | SL (mm, Mean ± SD) | BW (g, Mean ± SD) | Sex Ratio (♀:♂) | Stage of Sexual Maturity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May | 8 | 370.5 ± 38.1 | 423.8 ± 140.2 | 3:1 | Ⅰ–Ⅱ |

| Jun | 17 | 451.3 ± 90.6 | 997.4 ± 546.0 | 7:1 | Ⅱ |

| Jul | 8 | 517.8 ± 139.2 | 3228.4 ± 1626.5 | 7:1 | Ⅱ–Ⅲ |

| Sep | 9 | 541.2 ± 37.0 | 1314.5 ± 347.6 | 4:3 | Ⅱ–Ⅵ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, J.; Xiao, Z.; Jiang, R.; Xuan, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Cui, M. Tracking the Migratory Life History of Brown Croaker (Miichthys miiuy) Through Otolith Microchemistry in the East China Sea. Animals 2025, 15, 3129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213129

Shen J, Xiao Z, Jiang R, Xuan Z, Zhou Y, Li W, Wang H, Yang J, Cui M. Tracking the Migratory Life History of Brown Croaker (Miichthys miiuy) Through Otolith Microchemistry in the East China Sea. Animals. 2025; 15(21):3129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213129

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Jiarong, Zeyu Xiao, Rijin Jiang, Zhongya Xuan, Yongdong Zhou, Wenjia Li, Haoran Wang, Jian Yang, and Mingyuan Cui. 2025. "Tracking the Migratory Life History of Brown Croaker (Miichthys miiuy) Through Otolith Microchemistry in the East China Sea" Animals 15, no. 21: 3129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213129

APA StyleShen, J., Xiao, Z., Jiang, R., Xuan, Z., Zhou, Y., Li, W., Wang, H., Yang, J., & Cui, M. (2025). Tracking the Migratory Life History of Brown Croaker (Miichthys miiuy) Through Otolith Microchemistry in the East China Sea. Animals, 15(21), 3129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15213129