Morphological and Functional Evaluation of Kodkod (Leopardus guigna) Oocytes After In Vitro Maturation and Parthenogenetic Activation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Animals

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Ovariohysterectomy and Cumulus–Oocyte Complex Collection

2.5. Morphological Classification of Immature Cumulus–Oocyte Complexes

2.6. In Vitro Maturation of Oocytes

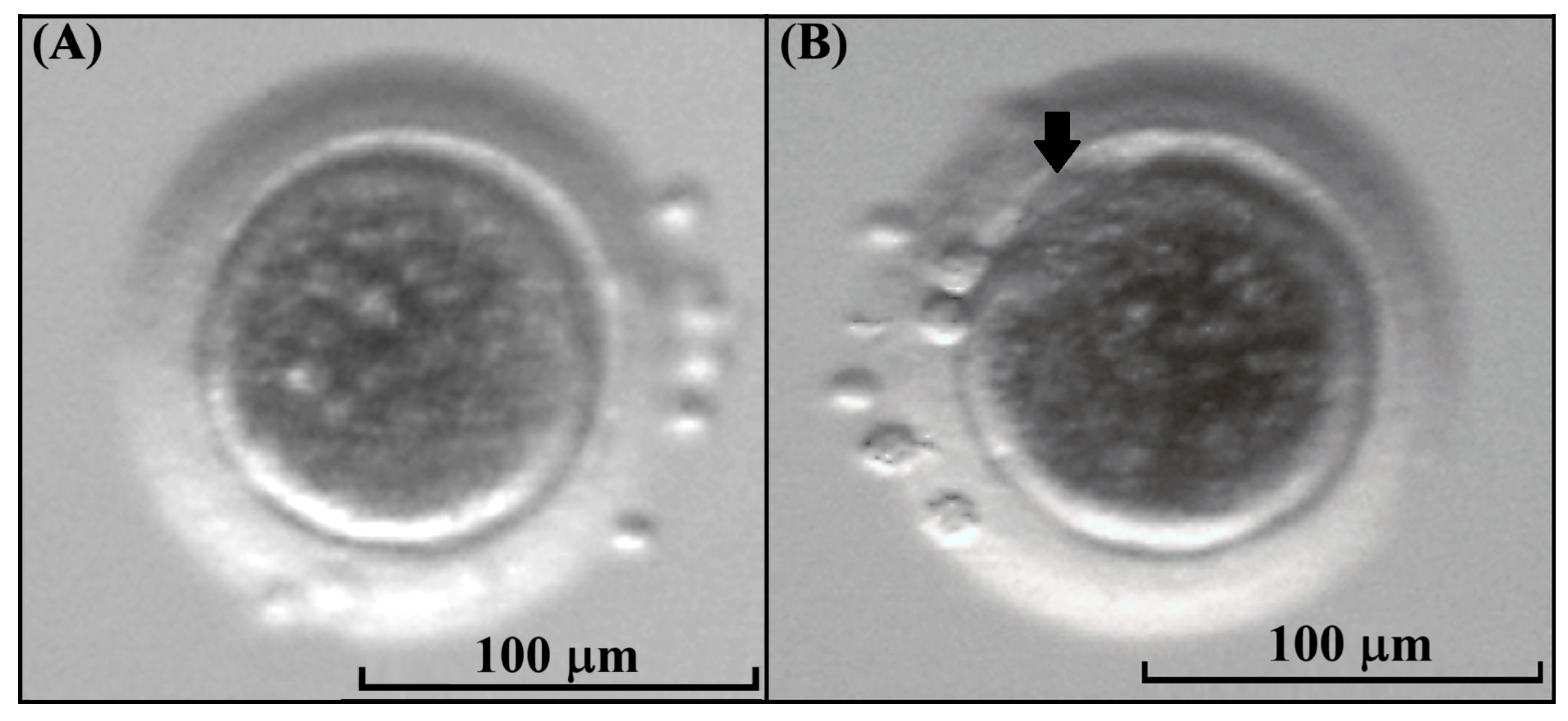

2.7. Evaluation of Cumulus Cell Expansion

2.8. Morphological Evaluation of Oocytes

2.9. Parthenogenetic Activation of Oocytes

2.10. Sperm Collection and In Vitro Fertilization

2.11. In Vitro Embryo Culture

2.12. Morphological Evaluation of Blastocysts

2.12.1. Diameter Measurement

2.12.2. Total Cell Counting

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Classification of Cumulus–Oocytes Complexes Recovered from Kodkod Ovaries

3.2. Evaluation of COCs Expiation in Kodkod and Domestic Cat After IVM

3.3. Assessment of Kodkod Oocyte Maturation and Morphological Comparison Against Domestic Cat Oocytes

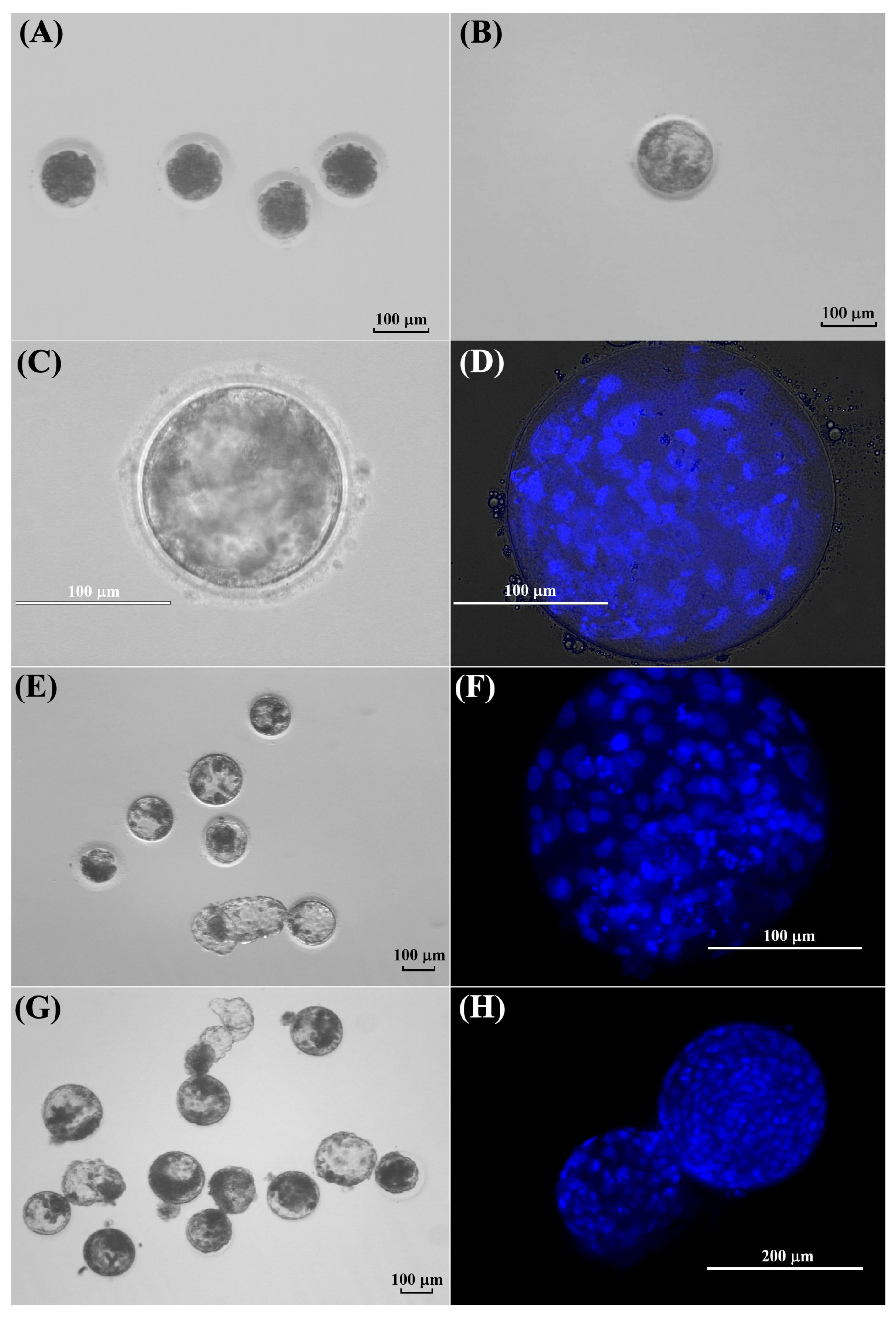

3.4. Evaluation of In Vitro Development of Kodkod and Domestic Cat Oocytes After Parthenogenetic Activation

3.5. Morphological Evaluation of Kodkod and Domestic Cat Blastocysts Obtained After Parthenogenetic Activation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2024-2. 2025. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Napolitano, C.; Gálvez, N.; Bennett, M.; Acosta-Jamett, G.; Sanderson, J. Leopardus guigna. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T15311A50657245. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/15311/50657245 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Napolitano, C.; Díaz, D.; Sanderson, J.; Johnson, W.E.; Ritland, K.; Ritland, C.E.; Poulin, E. Reduced genetic diversity and increased dispersal in Guigna (Leopardus guigna) in Chilean fragmented landscapes. J. Hered. 2015, 106, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.E. Aspects of in vivo oocyte production, blastocyst development, and embryo transfer in the cat. Theriogenology 2014, 81, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, C.E. Forty years of assisted reproduction research in non-domestic, wild and endangered mammals. Rev. Bras. Reprod. Anim. 2019, 43, 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, W.F. Practical application of laparoscopic oviductal artificial insemination for the propagation of domestic cats and wild felids. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2019, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraguas, D.; Gallegos, P.F.; Castro, F.O.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L. Cell cycle synchronization and analysis of apoptosis-related gene in skin fibroblasts from domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus) and kodkod (Leopardus guigna). Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017, 52, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraguas, D.; Aguilera, C.; Echeverry, D.; Saez-Ruiz, D.; Castro, F.O.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L. Embryo aggregation allows the production of kodkod (Leopardus guigna) blastocysts after interspecific SCNT. Theriogenology 2020, 158, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverry, D.M.; Rojas, D.M.; Aguilera, C.J.; Veraguas, D.M.; Cabezas, J.G.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, L.; Castro, F.O. Differentiation and multipotential characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue of an endangered wild cat (Leopardus guigna). Austral J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 51, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.S.; Mahesh, Y.U.; Suman, K.; Charan, K.V.; Nath, R.; Rao, K.R. Meiotic maturation of oocytes recovered from the ovaries of Indian big cats at postmortem. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2015, 51, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.A.; Donoghue, A.M.; O’Brien, S.J.; Wildt, D.E. Rescue and maturation in vitro of follicular oocytes collected from nondomestic felid species. Biol. Reprod. 1991, 45, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmel, J.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, L.; Jewgenow, K.; Müller, K. Felid-gamete-rescue within EAZA—Efforts and results in biobanking felid oocytes and sperm. J. Zoo Aquar. Res. 2019, 7, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez, L.; Hribal, R.; Stagegaard, J.; Zahmel, J.; Jewgenow, K. Production of lion (Panthera leo) blastocysts after in vitro maturation of oocytes and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paffoni, A.; Brevini, T.A.L.; Gandolfi, F.; Ragni, G. Parthenogenetic activation: Biology and applications in the ART laboratory. Placenta 2008, 29, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, V.S.; Wilton, L.J.; Moore, H.D. Parthenogenetic activation of marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) oocytes and the development of marmoset parthenogenones in vitro and in vivo. Biol. Reprod. 1998, 59, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozil, J.P. The parthenogenetic development of rabbit oocytes after repetitive pulsatile electrical stimulation. Development 1990, 109, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, M.H.; Barton, S.C.; Surani, M.A.H. Normal postimplantation development of mouse parthenogenetic embryos to the forelimb bud stage. Nature 1977, 265, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharche, S.D.; Birade, H.S. Parthenogenesis and activation of mammalian oocytes for in vitro embryo production: A review. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitalipov, S.M.; Nusser, K.D.; Wolf, D.P. Parthenogenetic activation of rhesus monkey oocytes and reconstructed embryos. Biol. Reprod. 2001, 65, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, J.S.; Leão, D.L.; Sampaio, R.V.; Brito, A.B.; Santos, R.R.; Miranda, M.S.; Ohashi, O.M.; Domingues, S.F. Embryo production by parthenogenetic activation and fertilization of in vitro matured oocytes from Cebus apella. Zygote 2013, 21, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praxedes, É.A.; Santos, M.V.D.O.; de Oliveira, L.R.M.; de Aquino, L.V.C.; de Oliveira, M.F.; Pereira, A.F. Synergistic effects of follicle-stimulating hormone and epidermal growth factor on in vitro maturation and parthenogenetic development of red-rumped agouti oocytes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2023, 58, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.A.; de Oliveira Santos, M.V.; Nascimento, L.E.; de Oliveira Lira, G.P.; Praxedes, É.A.; de Oliveira, M.F.; Pereira, A.F. Production of collared peccary (Pecari tajacu Linnaeus, 1758) parthenogenic embryos following different oocyte chemical activation and in vitro maturation conditions. Theriogenology 2020, 142, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.S.; Mahesh, Y.U.; Lakshmikantan, U.R.; Suman, K.; Charan, K.V.; Shivaji, S. Developmental competence of oocytes recovered from postmortem ovaries of the endangered Indian blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra). J. Reprod. Dev. 2010, 56, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmasani, S.R.; Yelisetti, U.M.; Katari, V.; Komjeti, S.; Lakshmikantan, U.; Pawar, R.M.; Sisinthy, S. Developmental ability after parthenogenetic activation of in vitro matured oocytes collected postmortem from deers. Small Rumin. Res. 2013, 113, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Swanson, W.F.; Herrick, J.R.; Lee, K.; Machaty, Z. Analysis of cat oocyte activation methods for the generation of feline disease models by nuclear transfer. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2009, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabiec, A.; Max, A.; Tischner, M. Parthenogenetic activation of domestic cat oocytes using ethanol, calcium ionophore, cycloheximide and a magnetic field. Theriogenology 2007, 67, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, J.; Nowak, A.; Niżański, W.; Prochowska, S.; Migdał, A.; Młodawska, W.; Witkowski, M. Developmental competence of cat (Felis domesticus) oocytes and embryos after parthenogenetic stimulation using different methods. Zygote 2018, 26, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.C.; Earle Pope, C.; Giraldo, A.; Lyons, L.A.; Harris, R.F.; King, A.L.; Cole, A.; Godke, R.A.; Dresser, B.L. Birth of African Wildcat cloned kittens born from domestic cats. Cloning Stem Cells 2004, 6, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.C.; Pope, C.E.; Ricks, D.M.; Lyons, J.; Dumas, C.; Dresser, B.L. Cloning endangered felids using heterospecific donor oocytes and interspecies embryo transfer. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2008, 21, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.C.; Wildt, D.E. Effect of the quality of the cumulus–oocyte complex in the domestic cat on the ability of oocytes to mature, fertilize and develop into blastocysts in vitro. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1997, 110, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, A.; Athanasiou, G.; Azari-Dolatabad, N.; Sadeghi, H.; Andueza, S.G.; Arcos, J.L.; Van Soom, A. Manual versus deep learning measurements to evaluate cumulus expansion of bovine oocytes and its relationship with embryo development in vitro. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 168, 107785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kij-Mitka, B.; Gabryś, J.; Kochan, J.; Nowak, A.; Szmatoła, T.; Prochowska, S.; Niżański, W.; Bugno-Poniewierska, M. Cat presumptive zygotes assessment in relation to their development. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2024, 24, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraguas, D.; Cuevas, S.R.; Gallegos, P.F.; Saez-Ruiz, D.; Castro, F.O.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L. eCG stimulation in domestic cats increases the expression of gonadotrophin-induced genes improving oocyte competence during the non-breeding season. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2018, 53, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Veraguas-Davila, D.; Cordero, M.F.; Saez, S.; Saez-Ruiz, D.; Gonzalez, A.; Saravia, F.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L. Domestic cat embryos generated without zona pellucida are capable of developing in vitro but exhibit abnormal gene expression and a decreased implantation rate. Theriogenology 2021, 174, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, E.C.; Nelson, R.W. Feline Reproduction. In Canine and Feline: Endocrinology and Reproduction, 3rd ed.; Saunders Elsevier Sciences: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1016–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, M.; Cubas, Z. Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of South American Wild Animals, 1st ed.; University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte, A. Mamíferos de Chile; Lynx Edition: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; pp. 220–221. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. Wild Cats Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1996; Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA28186204 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Castro, R. Establecimiento de un Banco Genético de Células Fibroblásticas de un Ejemplar Güiña (Oncifelis guigna); Universidad de Chile-Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias y Pecuarias: Santiago, Chile, 2007; Available online: http://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/130809 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Johnson, W.E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W.J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O’Brien, S.J. The late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment. Science 2006, 311, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, L.A.; Raymond, M.M.; O’Brien, S.J. Comparative genomics: The next generation. Anim. Biotechnol. 1994, 5, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, G.E.; O’Brien, S.J. A molecular phylogeny of the Felidae: Immunological distance. Evolution 1985, 39, 473–487. [Google Scholar]

- Duque Rodriguez, M.; Gambini, A.; Ratner, L.D.; Sestelo, A.J.; Briski, O.; Gutnisky, C.; Rulli, S.B.; Fernández Martin, R.; Cetica, P.; Salamone, D.F. Aggregation of Leopardus geoffroyi hybrid embryos with domestic cat tetraploid blastomeres. Reproduction 2021, 161, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.E.; Gomez, M.C.; Dresser, B.L. In vitro embryo production and embryo transfer in domestic and non-domestic cats. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge-Neto, P.N.; Requena, L.A.; de Araújo, G.R.; de Souza Traldi, A.; Luczinski, T.C.; de Deco-Souza, T.; Baldassarre, H. Efficient recovery of in vivo mature and immature oocytes from jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor) by Laparoscopic Ovum Pick-Up (LOPU). Theriogenology Wild 2023, 3, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz-Jaffe, M.G.; McCallie, B.R.; Preis, K.A.; Filipovits, J.; Gardner, D.K. Transcriptome analysis of in vivo and in vitro matured bovine MII oocytes. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Jia, G.; Li, A.; Ma, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Fu, X. RNA-Seq transcriptome profiling of mouse oocytes after in vitro maturation and/or vitrification. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Alkali, I.M.; Prochowska, S.; Luvoni, G.C. Fighting like cats and dogs: Challenges in domestic carnivore oocyte development and promises of innovative culture systems. Animals 2021, 11, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karja, N.W.K.; Otoi, T.; Murakami, M.; Fahrudin, M.; Suzuki, T. In vitro maturation, fertilization and development of domestic cat oocytes recovered from ovaries collected at three stages of the reproductive cycle. Theriogenology 2002, 57, 2289–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farstad, W. Current state in biotechnology in canine and feline reproduction. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2000, 60, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, R.E.; Wildt, D.E. Circannual variations in intraovarian oocyte but not epididymal sperm quality in the domestic cat. Biol. Reprod. 1999, 61, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, J.; Nowak, A.; Młodawska, W.; Prochowska, S.; Partyka, A.; Skotnicki, J.; Niżański, W. Comparison of the morphology and developmental potential of oocytes obtained from prepubertal and adult domestic and wild cats. Animals 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevoral, J.; Orsák, M.; Klein, P.; Petr, J.; Dvořáková, M.; Weingartová, I.; Jílek, F. Cumulus cell expansion, its role in oocyte biology and perspectives of measurement: A review. Sci. Agric. Bohem. 2015, 45, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnus, C.C.; De Matos, D.G.; Moses, D.F. Cumulus expansion during in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes: Relationship with intracellular glutathione level and its role on subsequent embryo development. Mol. Reprod. Dev. Inc. Gamete Res. 1998, 51, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmut, I.; Schnieke, A.E.; McWhir, J.; Kind, A.J.; Campbell, K.H. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 1997, 385, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewitzky, M.; Yamanaka, S. Reprogramming somatic cells towards pluripotency by defined factors. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007, 18, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, N.; Kim, L.; Shin, H.; Kong, I. In vitro production and initiation of pregnancies in inter-genus nuclear transfer embryos derived from leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) nuclei fused with domestic cat (Felis silverstris catus) enucleated oocytes. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Mai, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, L.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Q. Assessment of the developmental competence of human somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos by oocyte morphology classification. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasiene, K.; Lasys, V.; Glinskyte, S.; Valanciute, A.; Vitkus, A. Relevance and methodology for the morphological analysis of oocyte quality in IVF and ICSI. J. Reprod. Stem Cell Biotechnol. 2011, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Młodawska, W.; Maliński, B.; Godyń, G.; Nosal, B. Lipid content and G6PDH activity in relation to ooplasm morphology and oocyte maturational competence in the domestic cat model. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 24, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalia, B.; John, P.; Wiesława, M.; Wojciech, N.; Marzenna, P.O.; Katarzyna, H.L.; Małgorzata, O. Age-related changes in the cytoplasmic ultrastructure of feline oocytes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraguas-Dávila, D.; Saéz-Ruíz, D.; Álvarez, M.C.; Saravia, F.; Castro, F.O.; Rodríguez-Alvarez, L. Analysis of trophectoderm markers in domestic cat blastocysts cultured without zona pellucida. Zygote 2022, 30, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraguas-Dávila, D.; Caamano, D.; Saéz-Ruiz, D.; Vásquez, Y.; Saravia, F.; Castro, F.O.; Rodríguez-Alvarez, L. Zona pellucida removal modifies the expression and release of specific microRNAs in domestic cat blastocysts. Zygote 2023, 31, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veraguas-Dávila, D.; Zapata-Rojas, C.; Aguilera, C.; Saéz-Ruiz, D.; Saravia, F.; Castro, F.O.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L. Proteomic Analysis of Domestic Cat Blastocysts and Their Secretome Produced in an In Vitro Culture System without the Presence of the Zona Pellucida. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco-Jiménez, F.; Naturil-Alfonso, C.; Jiménez-Trigos, E.; Lavara, R.; Vicente, J.S. Influence of zona pellucida thickness on fertilization, embryo implantation and birth. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 132, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.X.; Ma, Y.Z.; Liu, Y.L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, C.J.; Wu, S.N.; Liang, C.G. Assessment of mouse germinal vesicle stage oocyte quality by evaluating the cumulus layer, zona pellucida, and perivitelline space. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Huang, T.; Wu, T.; Bai, H.; Kawahara, M.; Takahashi, M. Zona pellucida removal by acid Tyrode’s solution affects pre-and post-implantation development and gene expression in mouse embryos. Biol. Reprod. 2022, 107, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zhang, H. Embryological characteristics and clinical outcomes of oocytes with heterogeneous zona pellucida during assisted reproduction treatment: A retrospective study. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2020, 26, e924316-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.F.; Cho, S.J.; Bang, J.I.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Kwon, T.H.; Kong, I.K. Effect of equine chorionic gonadotropin on the efficiency of superovulation induction for in vivo and in vitro embryo production in the cat. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karja, N.W.K.; Otoi, T.; Murakami, M.; Wongsrikeao, P.; Budiyanto, A.; Fahrudin, M.; Nagai, T. Effect of cycloheximide on in vitro development of electrically activated feline oocytes. J. Reprod. Dev. 2005, 51, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Comizzoli, P.; Paulson, E.E.; McGinnis, L.K. The mutual benefits of research in wild animal species and human-assisted reproduction. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comizzoli, P.; Songsasen, N.; Wildt, D.E. Protecting and extending fertility for females of wild and endangered mammals. Oncofertility Ethical Leg. Soc. Med. Perspect. 2010, 156, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

| Group | N * | Total COCs | Grade I (%) | Grade II (%) | Grade I and II (%) | Grade III and IV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kodkod | 1 | 29 | 0 | 13 (44.8) | 13 (44.8) | 16 (55.2) |

| Domestic cat | 10 | 489 | 99 (20.3 ± 8.6) | 127 (25.9 ± 5.4) | 226 (46.2 ± 11.0) | 263 (53.8 ± 10.9) |

| Group | N * | Diameter Measurement (µm) | Area Measurement (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kodkod iCOCs | 13 | 170.8 ± 33.9 a | 21,042.9 ± 8198.2 a |

| Kodkod mCOCs | 13 | 222.7 ± 16.8 b | 35,874.5 ± 3921.2 b |

| Domestic cat iCOCs | 11 | 225.7 ± 40.3 b | 42,380.3 ± 16,451.3 c |

| Domestic cat mCOCs | 11 | 297.8 ± 85.4 c | 76,161.7 ± 42,536.0 d |

| Group | * Total Oocytes | Zona Pellucida Thickness (ZPT) | Oocyte Cytoplasm Diameter (OCD) | Total Oocyte Diameter (TOD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kodkod—Immature | 8 | 19.5 ± 2.0 | 106.3 ± 6.6 | 147.0 ± 9.1 a |

| Kodkod—MII | 5 | 19.9 ± 0.9 | 108.8 ± 6.7 | 152.6 ± 3.7 a |

| Total Kodkod | 13 | 19.8 ± 1.2 A | 107.3 ± 6.5 | 149.1 ± 7.8 A |

| Domestic cat—Immature | 11 | 20.9 ± 2.9 | 111.5 ± 6.3 | 165.5 ± 11.2 b |

| Domestic cat—MII | 16 | 21.9 ± 2.3 | 109.4 ± 3.7 | 164.9 ± 5.8 b |

| Total domestic cat | 27 | 21.5 ± 2.5 B | 110.3 ± 4.9 | 165.2 ± 8.2 B |

| Group | * N | Total Activated Oocytes | Cleavage N (%) | Morulae N (%) | Blastocysts N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kodkod—PA | 1 | 5 | 5/5 (100) | 2/5 (40.0) | 1/5 (20.0) a |

| Domestic cat—PA | 5 | 56 | 53/56 (94.6 ± 6.9) a | 33/53 (62.3 ± 13.9) | 11/53 (20.8 ± 4.5) a |

| Domestic cat—IVF | 5 | 138 | 56/138 (40.6 ± 20.8) b | 33/56 (58.9 ± 9.9) | 18/56 (32.1 ± 7.7) b |

| Group | * N | Total Cell Number (Mean ± SD) | Total Diameter (µm) (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kodkod—PA | 1 | 124.0 | 130.6 |

| Domestic cat—PA | 10 | 185.7 ± 78.9 a | 148.9 ± 34.6 |

| Domestic cat—IVF | 10 | 344.7 ± 199.9 b | 164.0 ± 21.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toledo-Saldivia, D.; Cáceres-Hernández, A.; Doussang, D.; Zapata-Rojas, C.; Vergara, S.; Carvacho, I.; Castro, F.O.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L.; Veraguas-Dávila, D. Morphological and Functional Evaluation of Kodkod (Leopardus guigna) Oocytes After In Vitro Maturation and Parthenogenetic Activation. Animals 2025, 15, 3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203031

Toledo-Saldivia D, Cáceres-Hernández A, Doussang D, Zapata-Rojas C, Vergara S, Carvacho I, Castro FO, Rodriguez-Alvarez L, Veraguas-Dávila D. Morphological and Functional Evaluation of Kodkod (Leopardus guigna) Oocytes After In Vitro Maturation and Parthenogenetic Activation. Animals. 2025; 15(20):3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203031

Chicago/Turabian StyleToledo-Saldivia, Deyna, Alonso Cáceres-Hernández, Daniela Doussang, Camila Zapata-Rojas, Sebastián Vergara, Ingrid Carvacho, Fidel Ovidio Castro, Lleretny Rodriguez-Alvarez, and Daniel Veraguas-Dávila. 2025. "Morphological and Functional Evaluation of Kodkod (Leopardus guigna) Oocytes After In Vitro Maturation and Parthenogenetic Activation" Animals 15, no. 20: 3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203031

APA StyleToledo-Saldivia, D., Cáceres-Hernández, A., Doussang, D., Zapata-Rojas, C., Vergara, S., Carvacho, I., Castro, F. O., Rodriguez-Alvarez, L., & Veraguas-Dávila, D. (2025). Morphological and Functional Evaluation of Kodkod (Leopardus guigna) Oocytes After In Vitro Maturation and Parthenogenetic Activation. Animals, 15(20), 3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15203031