Dog Guardian Interpretation of Familiar Dog Aggression Questions in the C-BARQ: Do We Need to Redefine “Familiar”?

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

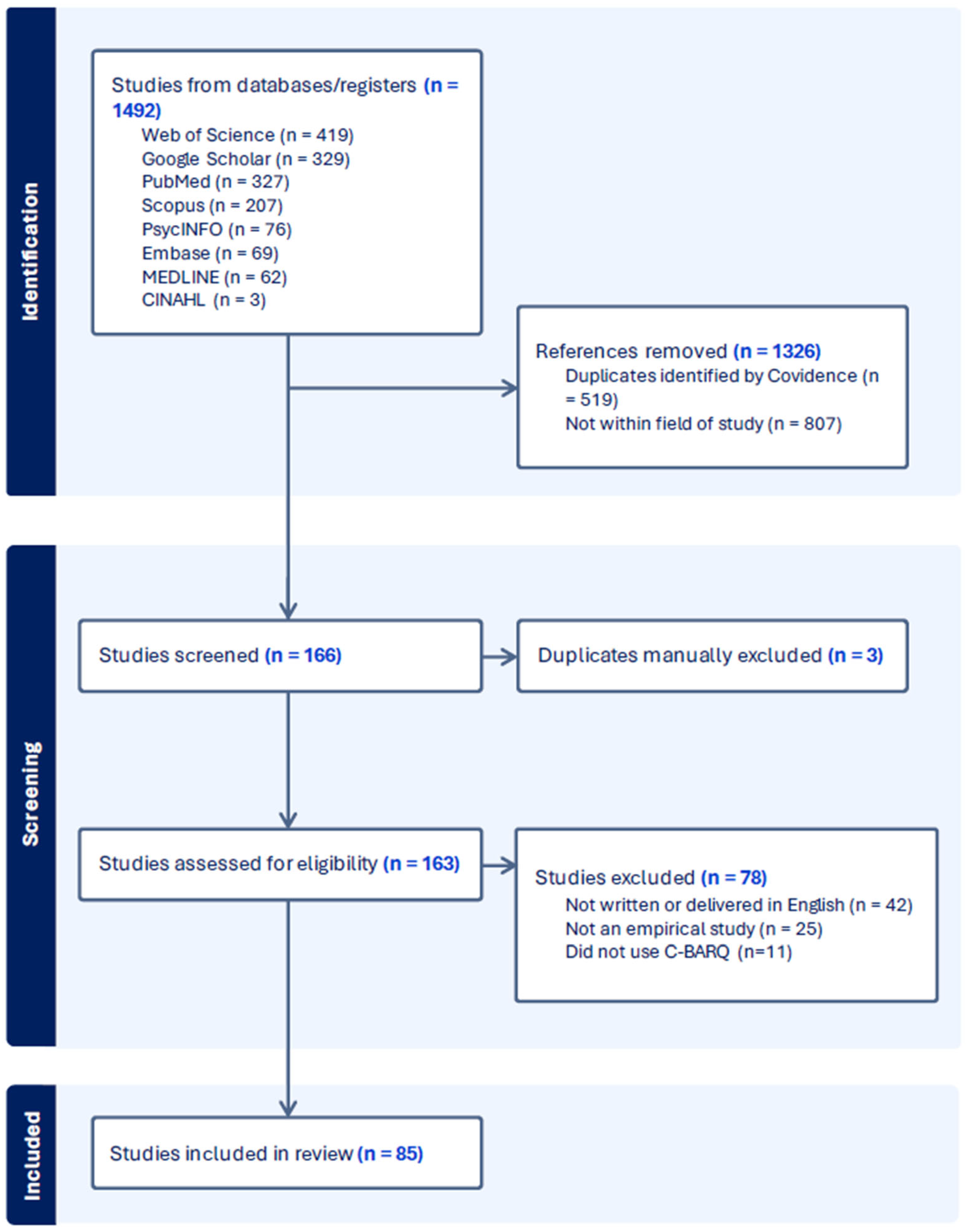

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study 1—Follow-Up FDA Questionnaires with Local Participants

3.1.1. Behavioural Profiles Differ in Singleton Dogs with FDA Scores

3.1.2. Reported Socialization Behaviour

3.1.3. Guardian Reasoning for Completing FDA Items

3.2. Study 2—Scoping Review

3.2.1. Definition of Familiar Dog Aggression

3.2.2. Missing Responses in C-BARQ Subscales

3.2.3. Quantitative Data Available for FDA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C-BARQ | Canine Behavioral Assessment and Research Questionnaire |

| FDA | Familiar Dog Aggression |

| DDF | Dog-Directed Fear |

| SDF | Stranger-Directed Fear |

| NSF | Non-Social Fear |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Scoping Review |

References

- Hsu, Y.; Serpell, J.A. Development and validation of a questionnaire for measuring behavior and temperament traits in pet dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About the CBARQ. Available online: https://vetapps.vet.upenn.edu/cbarq/about.cfm (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Duffy, D.L.; Serpell, J.A. Behavioral assessment of guide and service dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 2008, 3, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellowe, S.D.; Zhang, A.; Bignell, D.R.D.; Peña-Castillo, L.; Walsh, C.J. Gut microbiota composition is related to anxiety and aggression scores in companion dogs. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodman, N.H.; Brown, D.C.; Serpell, J.A. Associations between guardian personality and psychological status and the prevalence of canine behavior problems. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, E.; Joffe, E.; Wilson, C.; Serpell, J.; Otto, C.M. Behavior traits associated with career outcome in a prison puppy-raising program. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 236, 105218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, L.R.; Koch, C.S.; Serpell, J.; Campbell, K.L. Associations between atopic dermatitis and anxiety, aggression, and fear-based behaviors in dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2022, 58, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D.; Vanderstichel, R.; Stryhn, H.; Yu, J.; Serpell, J.A. Behavioural characteristics of dogs removed from hoarding situations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 178, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.; Duffy, D.; Serpell, J. Mental health of dogs formerly used as “breeding stock” in commercial breeding establishments. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, E.; Kelsey, K.M.; Niedermeyer, G.M.; Otto, C.M. Long-term behavioral resilience in search-and-rescue dogs responding to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 234, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouldice, V.L.; Edwards, A.M.; Serpell, J.A.; Niel, L.; Robinson, J.A.B. Expression of behavioural traits in goldendoodles and labradoodles. Animals 2019, 9, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumridge, M.H.; Suchak, M.; Hoffman, C.L. Guardian-reported attachment and behavior characteristics of New Guinea Singing Dogs living as companion animals. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, I.; Lilly, M.L.; Herron, M.E.; Serpell, J.A.; Alvarez, C.E. Genetic testing of dogs predicts problem behaviors in clinical and nonclinical samples. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, D.L.; Hsu, Y.; Serpell, J.A. Breed differences in canine aggression. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Arvelius, P.; Strandberg, E.; Polgar, Z.; Wiener, P.; Haskell, M.J. The interaction between behavioural traits and demographic and management factors in German Shepherd dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 211, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofgren, S.E.; Wiener, P.; Blott, S.C.; Sanchez-Molano, E.; Woolliams, J.A.; Clements, D.N.; Haskell, M.J. Management and personality in Labrador Retriever dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 156, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, D.L.; Serpell, J.A. Predictive validity of a method for evaluating temperament in young guide and service dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 138, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broseghini, A.; Guérineau, C.; Lõoke, M.; Mariti, C.; Serpell, J.; Marinelli, L.; Mongillo, P. Canine Behavioral Assessment and Research Questionnaire (C-BARQ): Validation of the Italian translation. Animals 2023, 13, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CBARQ. Published Articles Citing Use of the C-BARQ. Available online: https://vetapps.vet.upenn.edu/cbarq/published-articles.cfm (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Orne, M.T. Demand Characteristics. In Introducing Psychological Research: Sixty Studies That Shape Psychology; Banyard, P., Grayson, A., Eds.; Macmillan Education UK: London, UK, 1996; pp. 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalans, L.J. Frames, Framing Effects, and Survey Responses. In Handbook of Survey Methodology for the Social Sciences; Gideon, L., Ed.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Armstrong, R.A. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2014, 34, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Jamovi Project. 2025. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Caneijo-Teixera, R.; Almiro, P.A.; Serpell, J.A.; Baptista, L.V.; Niza, M.M.R.E. Evaluation of the factor structure of the canine behavioural assessment and research questionnaire (C-BARQ) in European Portuguese. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasawa, M.; Tsujimura, A.; Tateishi, K.; Mogi, K.; Ohta, M.; Serpell, J.A.; Kikusui, T. Assessment of the factorial structures of the C-BARQ in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2011, 73, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, N.; Jamshidi, S.; Serpell, J.A.; Mousavi, S.; Ghasempourabadi, Z. Assessment of the C-BARQ for evaluating dog behavior in Iran. J. Vet. Behav. 2015, 10, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Duffy, D.L.; Kruger, K.A.; Serpell, J.A. Evaluation of a behavioral assessment tool for dogs relinquished to shelters. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 117, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, L.; Paterson, M.B.A.; Bennett, P.; Perry, G.; Phillips, C.C.J. Comparison of canine behaviour scored using a shelter behaviour assessment and an owner completed questionnaire, C-BARQ. Animals 2020, 10, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.D.; Georgevsky, D.; Carrasco, J.; Valenzuela, M.; Duffy, D.L.; Serpell, J.A. Dog behavior co-varies with height, bodyweight and skull shape. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D.; Serpell, J.A.; Duffy, D.L.; Masaoud, E.; Dohoo, I.R. Differences in behavioral characteristics between dogs obtained as puppies from pet stores and those obtained from noncommercial breeders. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 242, 1359–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plueckhahn, T.C.; Schneider, L.A.; Delfabbro, P.H. Comparing guardian-rated dog temperament measures and a measure of guardian personality: An exploratory study. Anthrozoös 2023, 36, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, D.J.; Peters, R.A.; Marston, L.C.; De Groef, B. Investigating canine personality structure using guardian questionnaires measuring pet dog behaviour and personality. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 180, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A.; Duffy, D.L. Aspects of juvenile and adolescent environment predict aggression and fear in 12-Month-old guide dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooy, D.; Thomson, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D.; Wade, C.M. Risk factors of separation-related behaviours in Australian retrievers. App.l Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 209, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, I.; Eyre, A.W.; Alvarez, C.E.; Serpell, J.A. Latent class analysis of behavior across dog breeds reveal underlying temperament profiles. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.; Lee, B.; Reinhard, C.L.; Morris, M.; Satriale, D.; Serpell, J.; Watson, B. Returning a shelter dog: The role of owner expectations and dog behavior. Animals 2022, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauthier, L.M.; Williams, J.M. Using the mini C-BARQ to investigate the effects of puppy farming on dog behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 206, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.L.; Suchak, M. Dog rivalry impacts following behavior in a decision-making task involving food. Anim. Cogn. 2017, 20, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopresti-Goodman, S.; Bensmiller, N. Former laboratory dogs’ psychological and behavioural characteristics. Veterinární Medicína 2022, 67, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, Y.; Christiaen, E.; Wu, G.-R.; De Witte, S.; Vanhove, C.; Saunders, J.; Peremans, K.; Baeken, C. Structural connectome alterations in anxious dogs: A DTI-based study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.A.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Burns, N.R. Temperament and lateralization in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). J. Vet. Behav. 2013, 3, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.A.; Coe, J.B.; Widowski, T.M.; Pearl, D.L.; Niel, L. Defining and clarifying the terms canine possessive aggression and resource guarding: A study of expert opinion. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.A.; Coe, J.B.; Pearl, D.L.; Widowski, T.M.; Niel, L. Factors associated with canine resource guarding behaviour in the presence of dogs: A cross-sectional survey of dog guardians. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 161, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siracusa, C. Aggression - dogs. In Small Animal Veterinary Psychiatry; Deneberg, S., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2021; pp. 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.D.; Masters, A.M. Risk factors for separation-related distress and feed-related aggression in dogs: Additional findings from a survey of Australian dog guardians. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 109, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.A.; Pearl, D.L.; Coe, J.B.; Widowski, T.M.; Niel, L. Ability of owners to identify resource guarding behaviour in the domestic dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 188, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posluns, J.A.; Anderson, R.E.; Walsh, C.J. Comparing two canine personality assessments: Convergence of the MCPQ-R and DPQ and consensus between dog owners and dog walkers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 188, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiira, K.; Lohi, H. Early life experiences and exercise associate with canine anxieties. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, V.; Espinosa, U.B.; Crump, A.; Arnott, G. Canine socialisation: A narrative systematic review. Animals 2022, 12, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flint, H.E.; Coe, J.B.; Serpell, J.A.; Pearl, D.L.; Niel, L. Risk factors associated with stranger-direction aggression in domestic dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 197, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J. Psychometric Validity: Establishing the accuracy and appropriateness of psychometric measures. In The Wiley Handbook of Psychometric Testing: A Multidisciplinary Reference on Survey, Scale and Test Development; Irwing, P., Booth, T., Hughes, D.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 751–779. Available online: https://doi-org.qe2a-proxy.mun.ca/10.1002/9781118489772.ch24 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- McDowell, I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question Number | Question | Response Options |

|---|---|---|

| Q1–4 | Participant name, contact information, dog’s name and breed | |

| Q5 | How many dogs currently live in your home? | 1, 2, 3, 4+ |

| Q6 | How long has your household had this number of dogs? | Less than 1 month, 1–3 months, 3–6, 6–12, over 12 months |

| Q7 | If your dog currently lives alone, have they previously lived with another dog? | Yes, No, N/A |

| Q8 | If yes, which of the following statements best describes the transition from living with another dog to becoming the only dog in the household (Select multiple): | The other dog passed away; The other dog belonged to a friend/family member and living arrangements changed; The other dog was rehomed; The other dog was a temporary foster; Not applicable; Other |

| Q9 | Do you take your dog to visit other dogs at their home, or have other dogs over to visit at your home? If so, how frequently does this occur? These “other dogs” might belong to neighbours, family, or friends. | Never; Once a week or less; More than once a week; Every day |

| Q10 | Do you take your dog to socialize with other dogs away from a household environment (e.g., group walks/hikes with other dog owners, dog parks)? If so, how frequently does this occur? | Never; Once a week or less; More than once a week; Every day |

| Q11 | How would you describe the interactions/relationships of your dog with other dogs in your household? (Select all that apply): | They sleep together; They play together; They are tolerant of each other, but not playful; They are mostly tolerant, but occasionally fight (e.g., over food, toys, attention from owners); The “study” dog is fearful of other dogs in the home; They are aggressive with each other (regular fighting, dogs may be kept separated); Not applicable; Other (Please specify) |

| Q12 | Some dogs display aggressive behaviour from time to time. Typical signs of moderate aggression in dogs include barking, growling, and baring teeth. More serious aggression generally includes snapping, lunging, biting, or attempting to bite. By writing in the appropriate number from the scale, please indicate your own dog’s recent tendency to display aggressive behaviour in each of the following contexts: | |

| a | Towards another (familiar) dog in your household. | 0–4, N/A |

| b | When approached at a favorite resting/sleeping place by another (familiar) household dog. | 0–4, N/A |

| c | When approached while eating by another (familiar) household dog. | 0–4, N/A |

| d | When approached while playing with/chewing a favorite toy, bone, object, etc., by another (familiar) household dog. | 0–4, N/A |

| Q13 | In question 12, when rating your dog’s behaviour towards another dog in your household on a scale from 0 to 4, which of these statements best describes the “other” dog you were thinking of in that situation (Select Multiple): | Another dog that you own; A dog that you previously owned who lived with your current dog; A friend or family member’s dog who spends time with IN your home; A friend or family member’s dog who you spend time with AWAY from your home; Other (Please Specify) |

| Q14 | Is there anything else you would like to say about your dog’s interactions with other dogs? | Text response |

| FDA Scores | n | Mean ± SEM | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Cohort (2021) | 235 | 0.373 ± 0.05 | 0 | 0–4 |

| (170) | ||||

| Follow-up Cohort (2021 scores) | 71 | 0.343 ± 0.08 | 0 | 0–2 |

| (46) | ||||

| Follow-up Cohort (2022 scores) | 71 | 0.782 ± 0.11 | 0.5 | 0–2.75 |

| (57) |

| Question/Frequency | Total (n = 71) | Group 1 (n = 25) | Group 2 (n = 25) | Group 3 (n = 21) | Statistic |

| n % | n % | n % | n % | χ2 p | |

| In-Home Socialization | 14.0 0.026 | ||||

| Never | 16 22.5 | 3 12.0 | 9 36.0 | 4 19.1 | |

| Once/week or less | 43 60.5 | 13 52.0 | 15 60.0 | 16 76.2 | |

| More than once/week | 10 14.1 | 8 32.0 | 1 4.0 | 1 4.7 | |

| Every day | 2 2.8 | 1 4.0 | 0 0 | 1 4.7 | |

| Out-of-Home Socialization | 12.6 0.041 | ||||

| Never | 14 19.7 | 1 4.0 | 7 28.0 | 6 28.6 | |

| Once/week or less | 48 67.6 | 17 68.0 | 17 68.0 | 14 66.7 | |

| More than once/week | 7 9.9 | 5 20.0 | 1 4.0 | 2 9.5 | |

| Every day | 2 2.8 | 2 8.0 | 0 0 | 0 0 |

| Q13. “When rating your dog’s behaviour towards another dog in your household on a scale from 0–4, which of these statements best describes the ’other’ dog you were thinking of in that situation” | n |

| Another dog that you own | 21 |

| A dog that you previously owned who lived with your current dog | 4 |

| A friend or family member’s dog who spends time with your dog IN your home | 18 |

| A friend or family member’s dog who you spend time with AWAY from your home | 13 |

| No Response | 8 |

| Other (Please Specify) * | 7 |

| C-BARQ Version | FDA Reported | FDA Findings Significant |

|---|---|---|

| Full (n = 63) | 37/63 | 18/37 1 |

| Mini (42Q) (n = 11) | 7/11 | 4/7 2 |

| Modified/Unreported (n = 11) | 1/11 | 1/1 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pellowe, S.; Walsh, C. Dog Guardian Interpretation of Familiar Dog Aggression Questions in the C-BARQ: Do We Need to Redefine “Familiar”? Animals 2025, 15, 2876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15192876

Pellowe S, Walsh C. Dog Guardian Interpretation of Familiar Dog Aggression Questions in the C-BARQ: Do We Need to Redefine “Familiar”? Animals. 2025; 15(19):2876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15192876

Chicago/Turabian StylePellowe, Sarita, and Carolyn Walsh. 2025. "Dog Guardian Interpretation of Familiar Dog Aggression Questions in the C-BARQ: Do We Need to Redefine “Familiar”?" Animals 15, no. 19: 2876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15192876

APA StylePellowe, S., & Walsh, C. (2025). Dog Guardian Interpretation of Familiar Dog Aggression Questions in the C-BARQ: Do We Need to Redefine “Familiar”? Animals, 15(19), 2876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15192876