Morphological and Metric Analysis of Medieval Dog Remains from Wolin, Poland

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Context of Dog Domestication

1.2. The Human–Dog Relationship in Prehistory and the Early Medieval Period: Utility and Morphology

1.3. Cultural and Ritual Aspects of the Dog’s Presence

1.4. Osteological Materials in Polish Archeology

1.5. The History of Wolin: Previous Remains Studies and the Research Gap

1.6. Research Objectives

- Examining variability in linear dimensions of cranial and long bones and estimating withers’ height and body mass;

- Determining the range of morphotypic variation based on fragmentary material;

- Interpreting the possible functions these animals served within the Wolin community;

- Comparing the results with data from other areas of Pomerania.

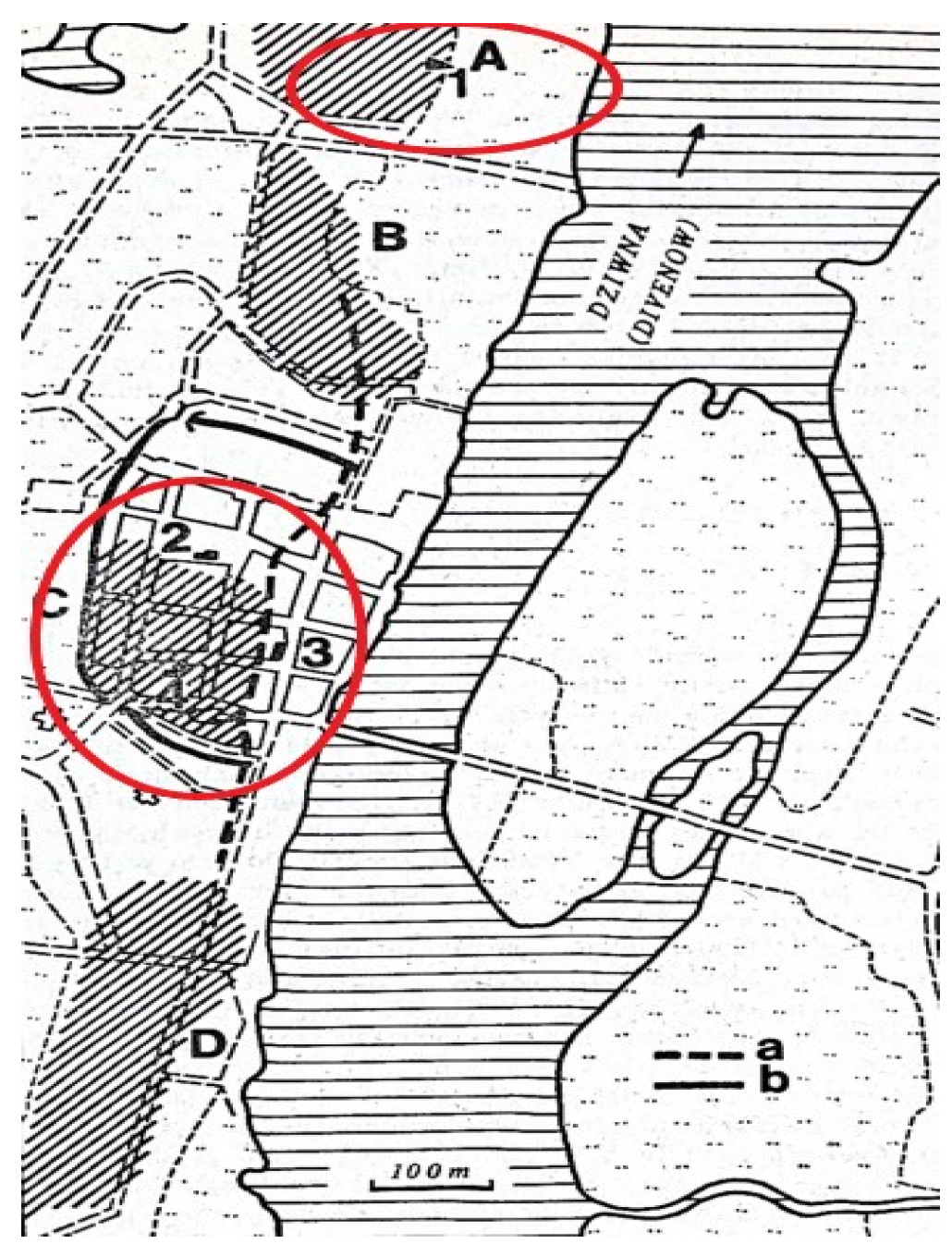

1.7. Archeological Context

1.8. Dating

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sex

3.2. Age

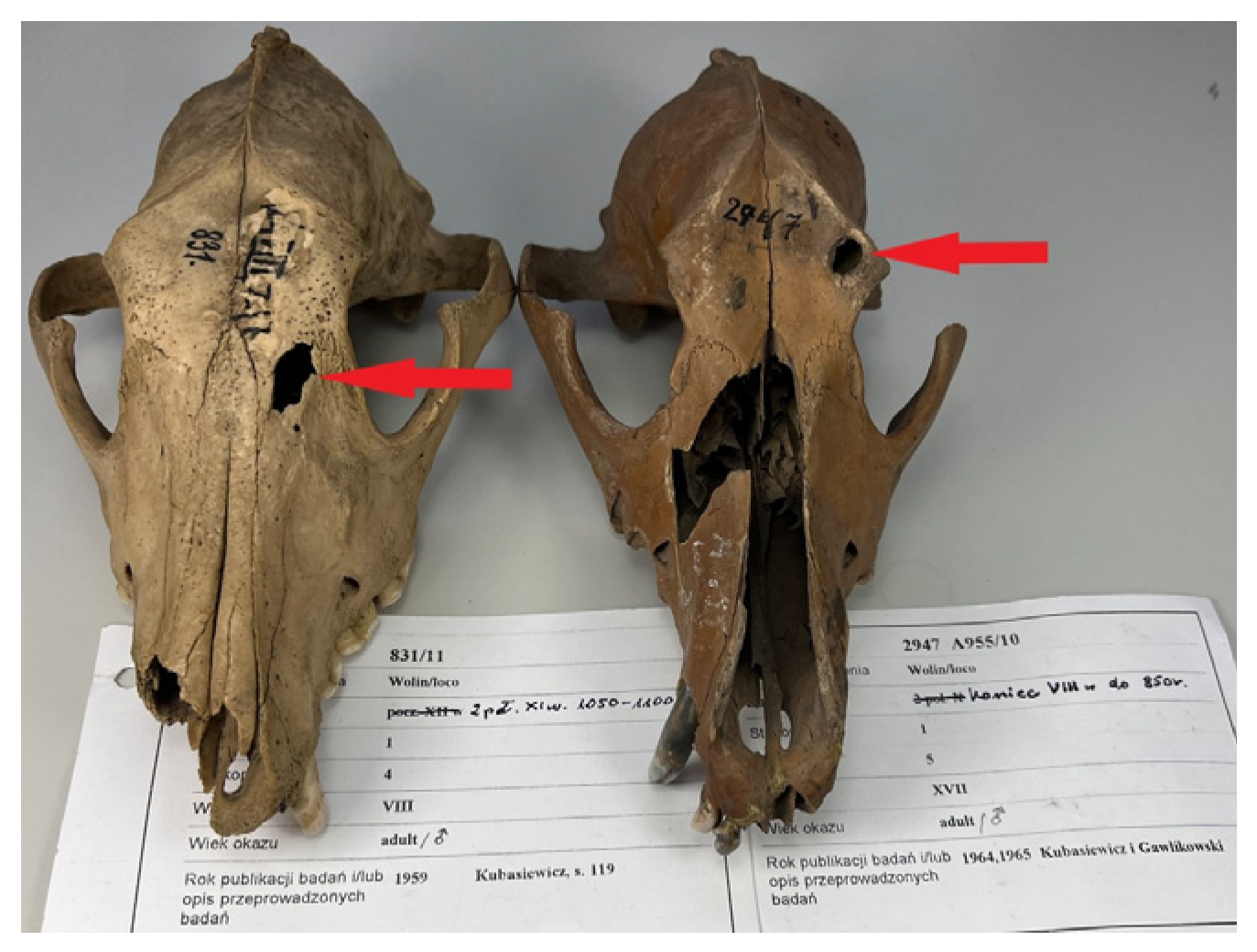

3.3. Evidence of Trauma or Damage to Skeletal Material

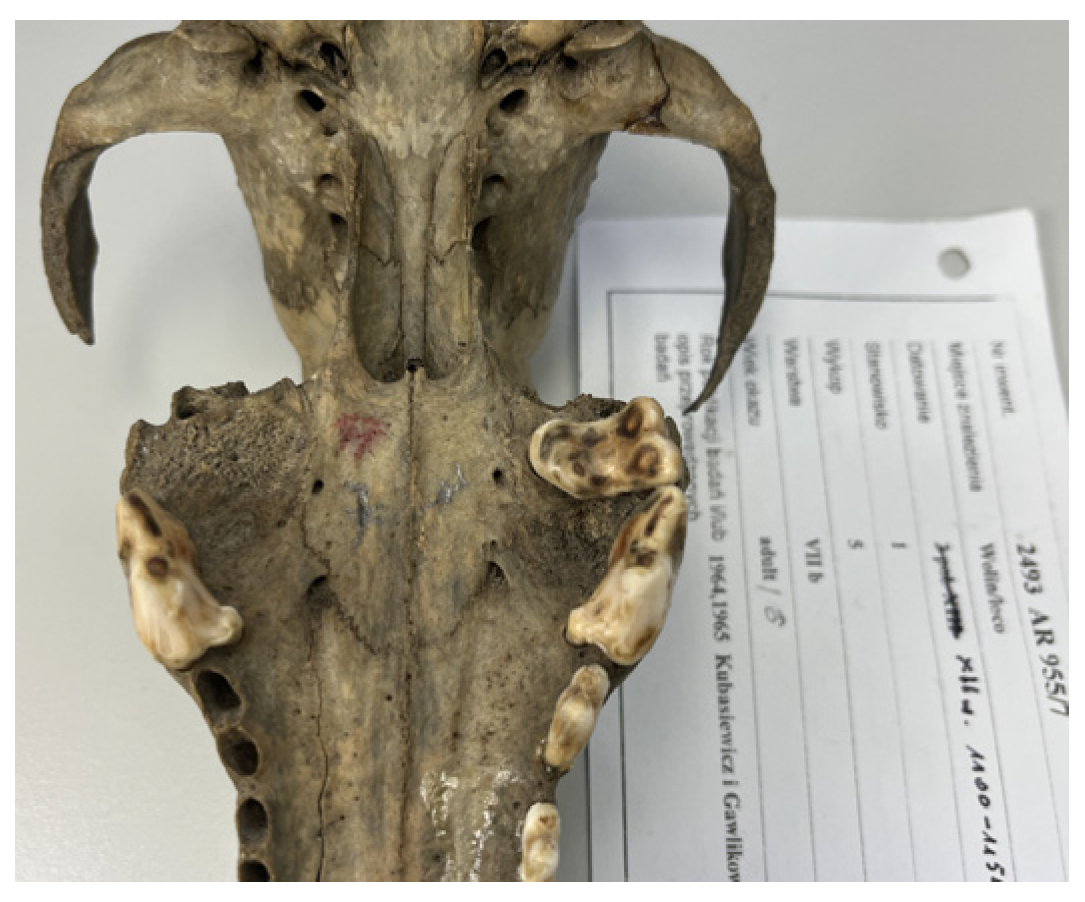

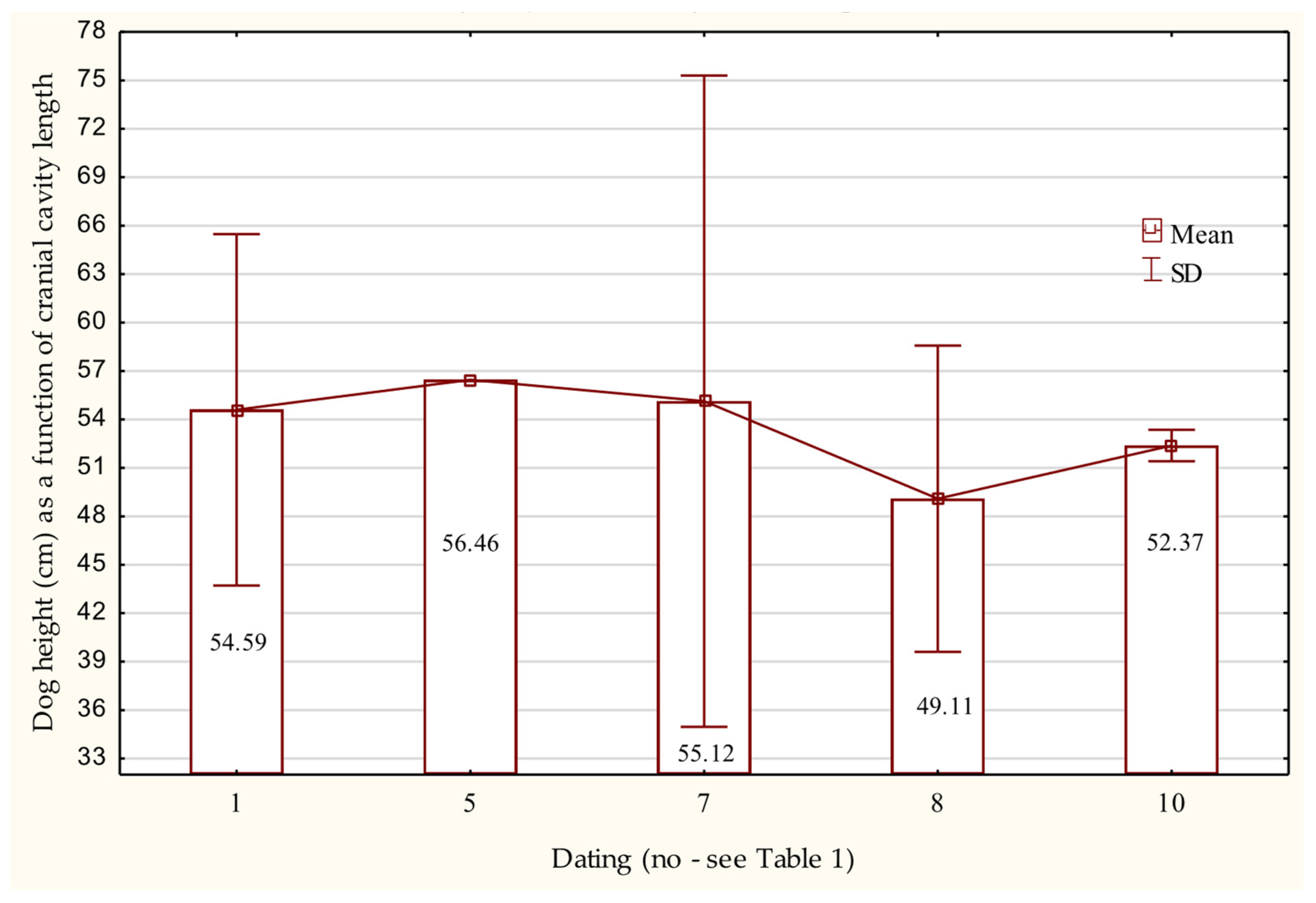

3.4. Osteometric Features of the Cranium

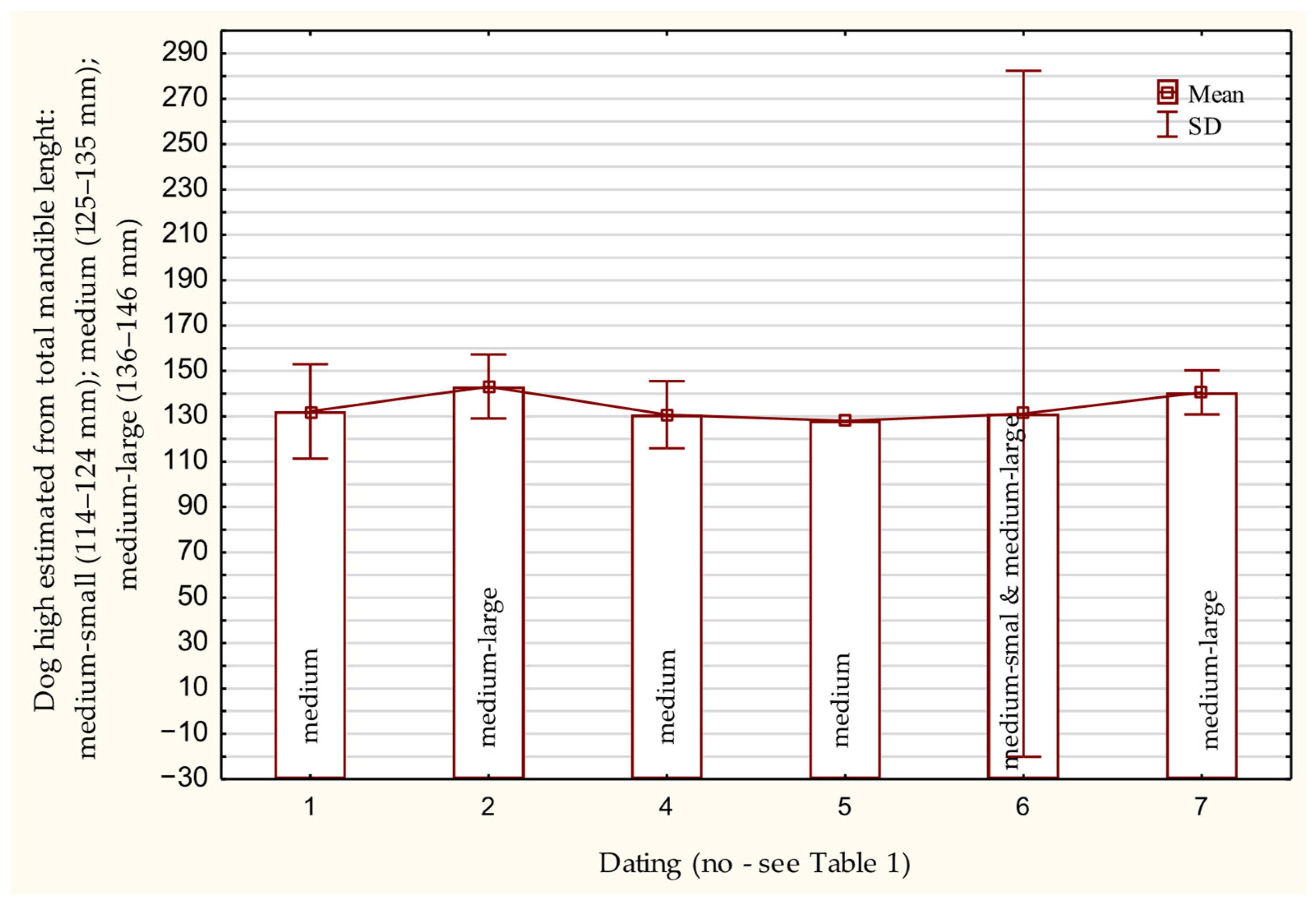

3.5. Osteometric Features of the Mandibula

3.6. Osteometric Features of the Pectoral Limb Bones

3.6.1. Scapula

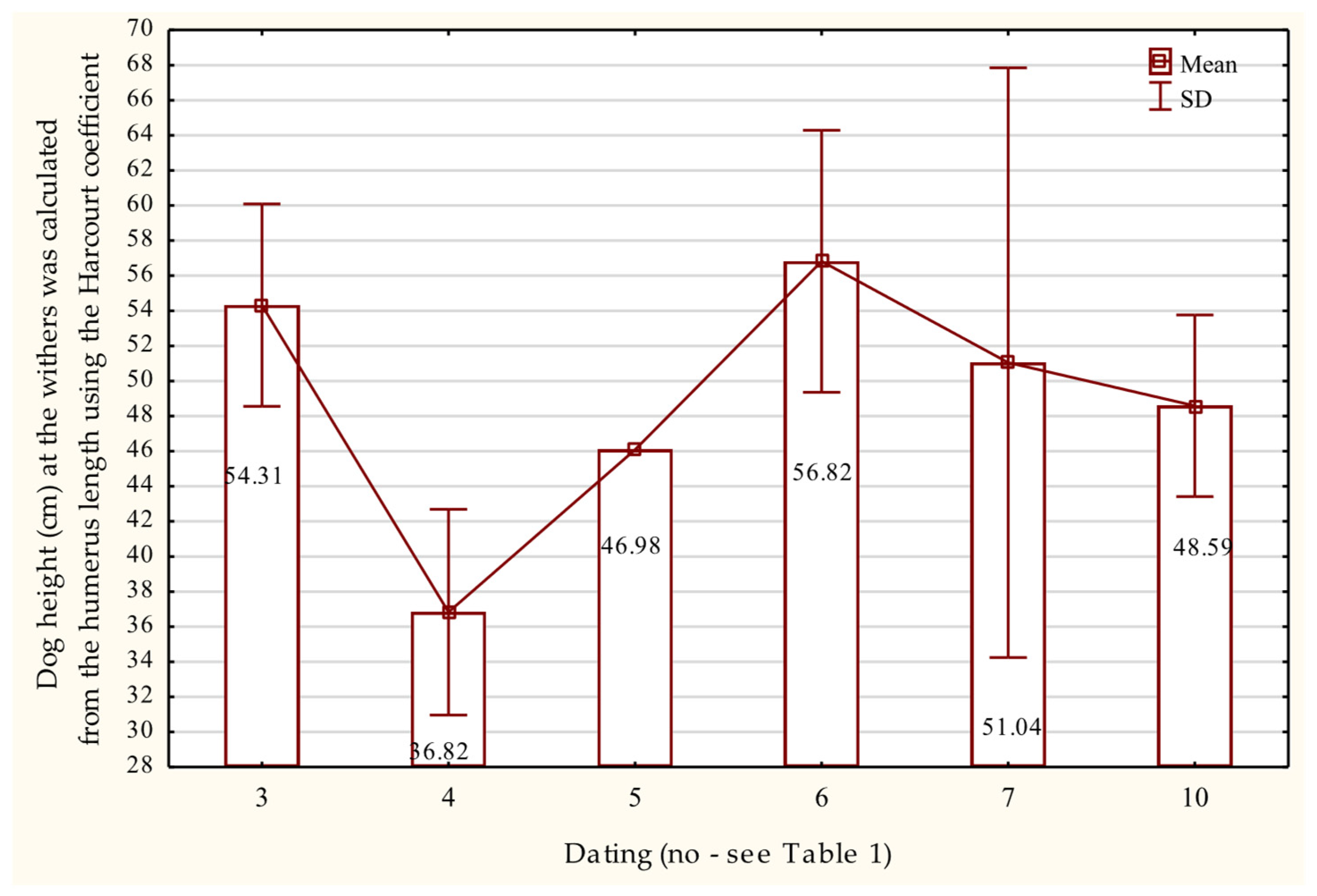

3.6.2. Humerus

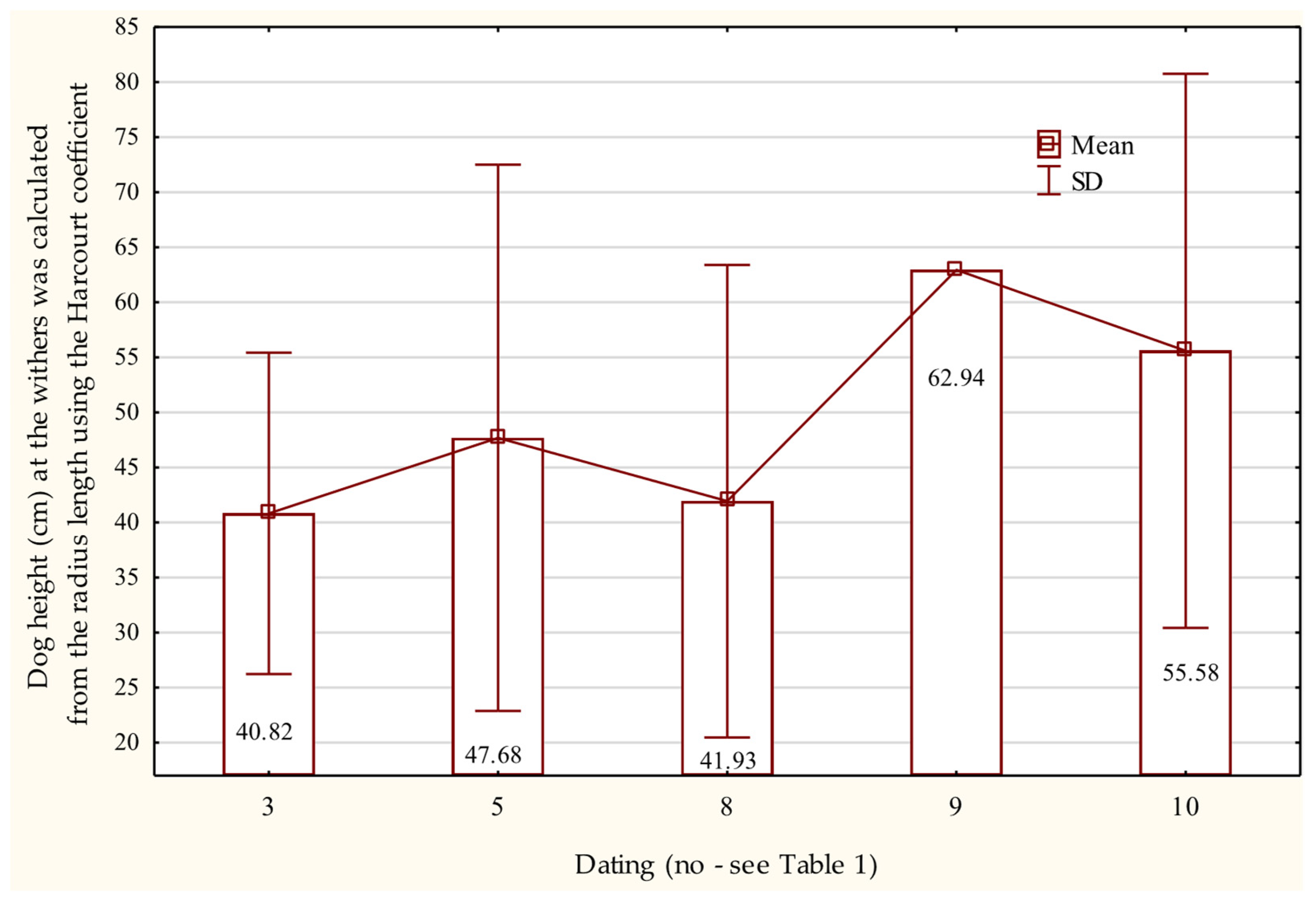

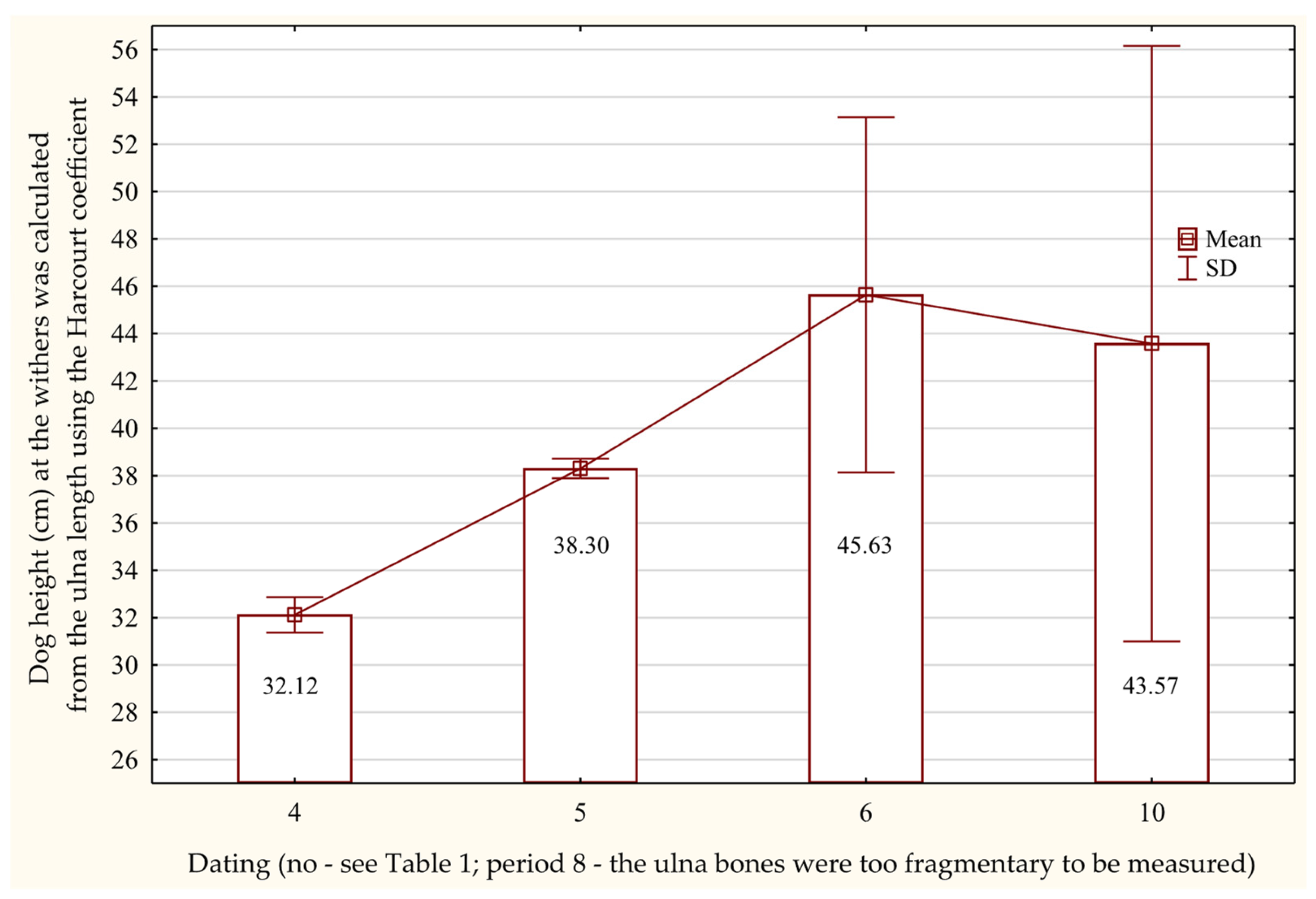

3.6.3. Radius and Ulna

| The Height (H) of the Dog Calculated According to | Statistical Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | x ± s | Min | Max | V% | |

| Wyrost i Kucharczyk [78] | |||||

| the cranial cavity H = 1.016 × D − 31.2 | 13 | 53.57 ± 5.39 | 45.74 | 66.64 | 10.12 |

| Mandible height at M1 (mm) according to Clark [97] | |||||

| 1. weight (kg) | 31 | 9.82 ± 2.14 | 4.38 | 14.36 | 21.77 |

| 2. weight (kg) | 31 | 15.10 ± 3.48 | 6.35 | 22.63 | 23.09 |

| Harcourt [25] | |||||

| humerus H = (3.43 × tl) − 26.54 | 15 | 49.58 ± 9.71 | 31.64 | 62.10 | 19.59 |

| radius H = (3.18 × tl) +19.51 | 19 | 48.47 ± 11.89 | 33.36 | 65.50 | 24.53 |

| ulna H = (2.78 × tl) + 6.21 | 12 | 41.30 ± 9.61 | 27.39 | 62.06 | 23.26 |

| femur H = (3.14 × tl) − 12.96 | 13 | 50.52 ± 11.32 | 29.79 | 65.90 | 22.42 |

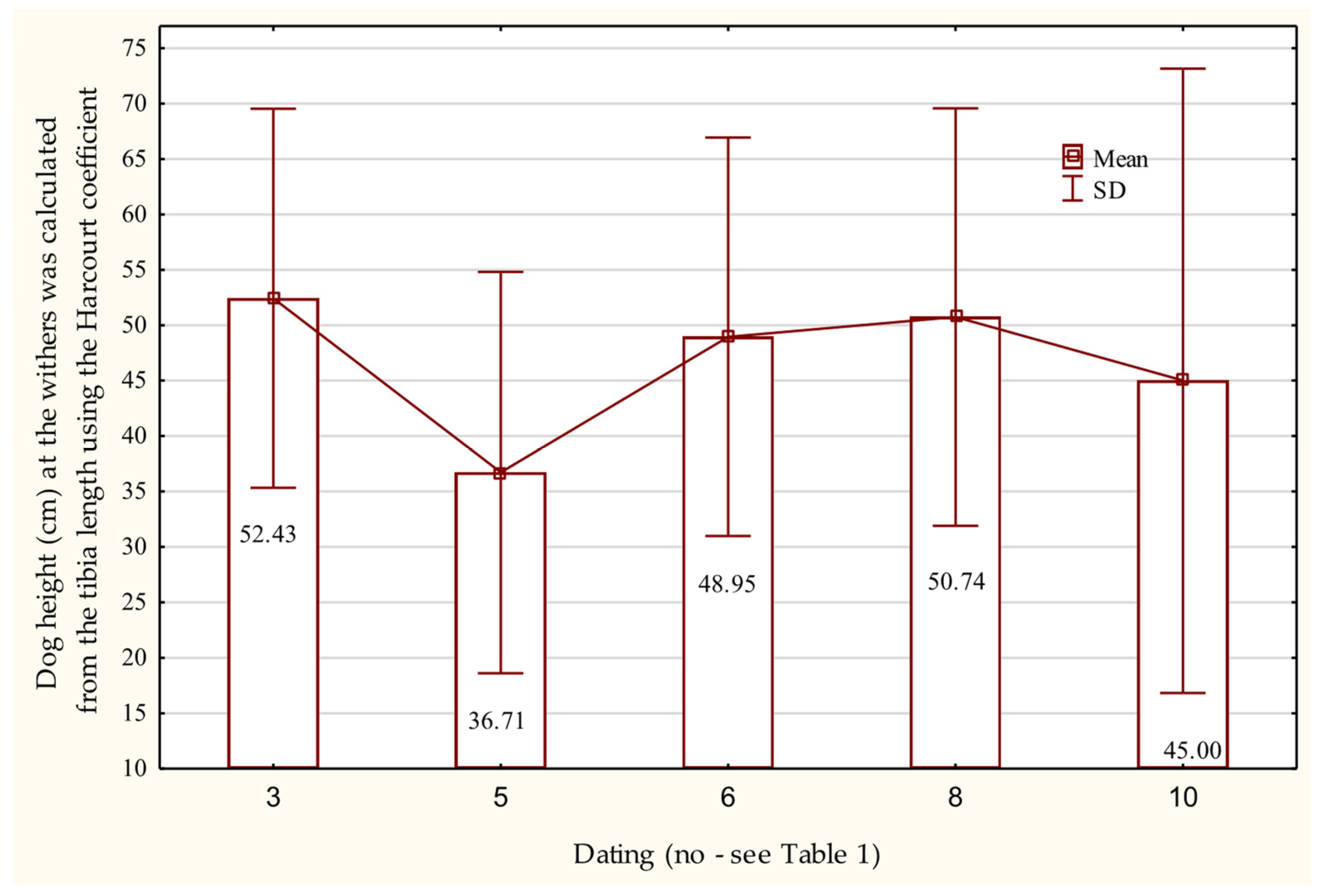

| tibia H = (2.92 × tl) + 9.41 | 21 | 47.34 ± 10.71 | 27.15 | 61.32 | 22.62 |

| Lasota-Moskalewska [93] | |||||

| scapula H = tl × 4.06 | 5 | 51.54 ± 8.14 | 37.63 | 58.46 | 15.79 |

| humerus H = tl × 3.37 | 15 | 51.33 ± 9.54 | 33.70 | 63.62 | 18.59 |

| radius H = tl × 3.22 | 19 | 47.11 ± 12.04 | 29.78 | 65.36 | 25.56 |

| ulna H = tl × 2.67 | 12 | 39.07 ± 9.23 | 25.71 | 59.01 | 23.61 |

| femur H = tl × 3.01 | 13 | 49.67 ± 10.86 | 29.80 | 64.41 | 21.85 |

| tibia H = tl × 2.92 | 21 | 46.41 ± 10.71 | 27.15 | 61.32 | 23.08 |

| Femur circumference (mm) according to Clark [97] | |||||

| 3. Weight (kg) | 16 | 26.84 ± 8.84 | 9.09 | 41.15 | 32.93 |

| Weight estimation (kg) according to Onar [36] | |||||

| W = 10(2.47×log (h))−2.27 | 28 | 19.13 ± 6.08 | 6.84 | 33.00 | 31.76 |

| W = 10(2.88×log (f))−3.4 | 16 | 17.45 ± 5.78 | 5.86 | 26.84 | 33.13 |

3.7. Osteometric Features of the Pelvic Limb Bones

Femur and Tibia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Day, L.P. Dog Burials in the Greek World. AJA 1984, 88, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlander, F. A Piece of the Mesolithic Horizontal Stratigraphy and Bodily Manipulations at Skateholm. In The Materiality of Death: Bodies, Burials, Beliefs; BAR International Series 1768; Fahlander, F., Oestigaard, T., Eds.; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gardeła, L. Pies w świecie Wikingów. In Człowiek Spotyka Psa; Borkowski, T., Ed.; Muzeum Miejskie Wrocławia: Wrocław, Poland, 2012; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mannermaa, K.; Ukkonen, P.; Viranta, S. Prehistory and early history of dogs in Finland. Fennosc. Archaeol. 2014, XXXI, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, B.L. Analysing breed and gender differences in behaviour. In The domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People; Serpell, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, K. Man Meets Dog; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002; Originally published in 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Coppinger, R.; Schneider, R. Evolution of working dogs. In The domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People; Serpell, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, G.; Karlsson, E.K.; Perri, A.; Webster, M.T.; Ho, S.Y.; Peters, J.; Lindblad-Toh, K. Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8878–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morey, D. The early evolution of the domestic dog. Am. Sci. 1994, 82, 336–347. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà, C.; Savolainen, P.; Maldonado, J.E.; Amorim, I.R.; Rice, J.E.; Honeycutt, R.L.; Crandall, K.A.; Lundeberg, J.; Wayne, R.K. Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog. Science 1997, 276, 1687–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.J.M.; Valla, F.R. Evidence for domestication of the dog 12 000 years ago in Natufian of Israel. Nature 1978, 276, 608–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobis, G. Der älteste Haushunde lebte vor 14000 Jahren. Umschau 1979, 79, 610. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, M.E. The Lost History of the Canine Race: Our 15,000-Year Love Affair with Dogs; Andrews and McMeel Publishing: Kansas City, MO, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Germonpre, M.; Sablin, M.V.; Stevens, R.E.; Hedges, R.E.M.; Hofreiter, M.; Stiller, M.; Despre, V.R. Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: Osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeta, P.; Lázničková-Galetová, M.; Sablin, M.; Germonpré, M. Morphological evidence for early dog domestication in the European Pleistocene: New evidence from a randomization approach to group differences. Anat. Rec. 2021, 304, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clutton-Brock, J. Origins of the dog: The archaeological evidence. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People; Clutton-Brock, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zeuner, F.E. The dog. In A History of Domesticated Animals; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1963; pp. 79–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bogolubski, S. Pochodzenie I Ewolucja Zwierząt Domowych; PWRiL: Warszawa, Poland, 1968; pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, H. The Origin of the Domestic Animals of Africa; Africana Publication Corporation: Trenton, NJ, USA, 1971; Volume 1, pp. 1–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bökönyi, S. History of Domestic Mammals in Central and Eastern Europe; Akadēmiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, S.A.; Smaers, J.B.; Serpell, J.A.; Hecht, E.E. Brain–Behavior Differences in Premodern and Modern Lineages of Domestic Dogs. J. Neurosci. 2025, 45, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rütimeyer, L. Die Fauna Der Pfahlbauten in der Schweiz: Untersuchungen Über Die Geschichte Der Wilden Und Der Haus-Säugethiere Von Mittel-Europa; Bahnmaier’s Buchhandlung (C. Detloff): Winterthur, Switzerland, 1861. [Google Scholar]

- Studer, T.R. Chasse et Pêche: Instructions Pour L’inspection Fédérale des Forêts, de la Chasse et de la Pêche; Département fédéral de l’intérieur, Inspection fédérale des forêts, de la chasse et de la pêche: Berne, Switzerland, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, L. The mesolithic of southern scandinavia. J. World Prehistory 1990, 4, 257–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcourt, R.A. The Dog in prehistoric and early historic Britain. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1974, 1, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serjeantson, D. Review Of Animal Remains From The Neolithic And Early Bronze Age Of Southern Britain (4000BC-1500BC); Archaeological Science; Research Department Report Series no. 29-2011; Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA): London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zedda, M.; Manca, P.; Chisu, V.; Gadau, S.; Lepore, G.; Genovese, A.; Farina, V. Ancient Pompeian Dogs—Morphological and Morphometric Evidence for Different Canine Populations. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2006, 35, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osypińska, M.; Skibniewski, M.; Osypiński, P. Ancient Pets. The health, diet and diversity of cats, dogs and monkeys from the Red Sea port of Berenice (Egypt) in the 1st–2nd centuries AD. World Archaeol. 2020, 52, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grossi Mazzorin, J.; Minniti, C. Le sepolture di cani della necropoli di età imperiale di Fidene-via Radicofani (Roma): Alcune considerazioni sul loro seppellimento nell’antichità. In Atti del 2 Convegno Nazionale di Archeozoologia; Abaco Edizioni: Sardinia, Italy, 2000; pp. 387–398. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, M.; Belanger, K. In sickness and in health: Care for an arthritic Maltese dog from the Roman cemetery of Yasmina, Carthage, Tunisia. In Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction, Proceedings of the 9th ICAZ Conference, Durham, Great Britain, 23–28 August 2002; Snyder, L., Moore, E.A., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 38–43. ISBN 978 1 785 70399 7. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C.; Baxter, I.L.; Nussbaumer, M. The application of discriminant function analysis to archaeological dog remains as an aid to the elucidation of possible affinities with modern breeds. Archaeofauna 2009, 18, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenebeck, J.J.; Hutchinson, S.A.; Byers, A.; Beale, H.C.; Carrington, B.; Faden, D.L.; Rimbault, M.; Decker, B.; Kidd, J.M.; Sood, R.; et al. Variation of BMP3 Contributes to Dog Breed Skull Diversity. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluskowski, A. The zooarchaeology of medieval ‘Christendom’: Ideology, the treatment of animals and the making of medieval Europe. World Archaeol. 2010, 42, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowiecki, D. Remarks on the ‘Breeds’ of dog (Canis lupus f. familiaris) in the Polish Lowland in the Roman Period, the Middle Ages and Post-Medieval Times in the light of archaeozoological research. Fasc. Archaeolgiae Hist. 2006, 8, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Piličiauskienė, G.; Skipitytė, R.; Micelicaitė, V.; Blaževičius, P. Dogs in Lithuania from the 12th to 18th C AD: Diet and health according to stable isotope, zooarchaeological, and historical data. Animals 2024, 14, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onar, V. Estimating the body weight of dogs unearthed from the Van-Yoncatepe Necropolis in Eastern Anatolia. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2005, 29, 495–498. [Google Scholar]

- Onar, V.; Janeczek, M.; Pazvant, G.; Gezerince, N.; Alpak, H.; Armutak, A.; Chrószcz, A.; Kiziltan, Z. Estimating the Body Weight of Byzantine Dogs from the Theodosius Harbour at Yenikapı, Istanbul. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg 2015, 21, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méniel, P. Les animaux de la nécropole gallo-romaine de Vertault (Côte d’Or, France). Archaeobiologiae Doc. 2007, 5, 249–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, S. Man’s best friend for eternity: Dog and human burials in ancient Egypt. Anthropozoologica 2013, 48, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, M.L. Paws in the Sand: The Emergence and Development of the Use of Canids in 459 the Funerary Practice of the Ancient EGYPTIANS (ca. 5000 BC–395 AD). Ph.D. Thesis, Macquarie University, Department of Ancient History, Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.N. Prehistoric cognition and the science of archaeology. In Elements of Cognitive Archaeology; Renfrew, C., Zubrow, E.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx, S.; Eyckerman, M. Visual representation and state development in Egypt. Archéo-Nil 2012, 22, 23–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassard, C. Le chien en egypte ancienne: Approche archeozoologique et apports de la craniology. Paleobios 2018, 20, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Makiewicz, T. Znaczenie sakralne tak zwanych ”pochówków psów” na terenie środkowoeuropejskiego Barbaricum. Folia Praehist. Posnaniensia 1987, 2, 239–277. [Google Scholar]

- Albizuri, S.; Nadal, J.; Martin, P.; Gibaja, J.F.; Cólliga, A.M.; Esteve, X.; Oms, X.; Marti, M.; Pou, R.; López-Onaindia, D.; et al. Dogs in funerary contexts during the Middle Neolithic in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula (5th–early 4th millennium BCE). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2019, 24, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, P.; Saladié, P.; Nadal, J.; Vergès, J.M. Butchered and consumed: Small carnivores from the Holocene levels of El Mirador Cave (Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain). Quat. Int. 2014, 353, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Pellicena, M.A.; Sala, N.; De Gaspar, I.; Iriarte, E.; Blázquez-Orta, R.; Arsuaga, J.L.; Carretero, J.M.; García, N. Long-term dog consumption during the Holocene at the Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain): Case study of the El Portalón de Cueva Mayor site. Archaeol. Anthr. Sci. 2022, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Ó Baoill, R. It’s a Dog’s Life: Butchered Medieval Dogs from Carrickfergus, Co. Antrim. Archaeol. Irel. 2000, 14, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, J.R.; Santos-Fita, D.; González, J.A. The therapeutic use of the dog in Spain: A review from a historical and cross-cultural perspective of a change in the human-dog relationship. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2017, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajkowski, K. The Dog in Pagan Beliefs of Early Medieval North-Western Slavs. Analecta Archaeol. Ressoviensia 2015, 10, 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Niezabitowski, E.L. Szczątki zwierzęce z osady neolitycznej w Rzucewie na polskim wybrzeży Bałtyku. Przegląd Archeol. 1928, 4, 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wodzicki, K. Studia nad prehistorycznymi psami Polski. Wiadomości Archeol. 1935, XIII, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Krysiak, K. Szczątki zwierzęce z osady neolitycznej w Ćmielowie. Wiadomości Archeol. 1950, 17, 165–226. [Google Scholar]

- Krysiak, K. Materiał zwierzęcy z osady neolitycznej w Gródku Nadbużnym, powiat Hrubieszów. Wiadomości Archeol. 1956, 23, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wasilewski, W. Czaszka psa neolitycznego ze Strzyżowa nad Bugiem. Ann. UMCS 1950, sect. F, 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Krysiak, K. Szczątki zwierzęce z Grodziska we wsi Sąsiadka powiat Zamość. Światowit 1966, XXVII, 171–201. [Google Scholar]

- Krysiak, K. Szczątki zwierzęce z wykopalisk w Gdańsku. Gdańsk wczesnośredniowieczny. Gdańskie Tow. Nauk. 1967, VI, 7–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gawlikowski, J. Szczątki zwierzęce z badań sondażowych na wczesnośredniowiecznym stanowisku nr 6 w Szczecinie. Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 1969, 15, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Gręzak, A.; Kurach, B. Konsumpcja mięsa w średniowieczu oraz w czasach nowożytnych na terenie obecnych ziem polskich w świetle danych archeologicznych. Archeol. Pol. 1996, XLI, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Pankiewicz, A.; Jaworski, K.; Chrószcz, A.; Poradowski, D. Dogs in the Wroclaw Stronghold, 2nd Half of the 10th–1st Half of the 13th Century (Lower Silesia, Poland)—An Zooarchaeological Overview. Animals 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachnowski, K. Josmborg. (Normanowie Wobec Polski W Wieku X): Studium Historyczne. In Prace Towarzystwa Naukowego Warszawskiego, II. Wydział Nauk Antropologicznych, Społecznych, Historycznych i Filozofii; Flatau, E., Ed.; Société des Sciences de Varsovie: Warszawa, Poland, 1914; Volume 11, pp. 2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Petrulevich, A. One etymolog of at Jómi, Jumne and Jómsborg. Namn Och Bygd 2009, 97, 65–97. [Google Scholar]

- Morawiec, J. Wolin W Średniowiecznej Tradycji Skandynawskiej; Avalon: Kraków, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stanisławski, B.; Filipowiak, W. Wolin Wczesnośredniowieczny; 1. Wyd; Foundation for Polish Science, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; ISBN 9788374362498. [Google Scholar]

- Leciejewicz, L. Początki Nadmorskich Miast na Pomorzu Zachodnim (Anfänge der Seestädte in West-Pommern); Z. N. im. Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland; Warszawa, Poland; Kraków, Poland, 1962; p. 377. [Google Scholar]

- Filipowiak, W. Wolinianie (Die Wolliner); PWN: Poznań, Poland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Cnotliwy, E.; Łosiński, W.ł.; Wojtasik, J. Rozwój przestrzenny wczesnośredniowiecznego Wolina w świetle analizy porównawczej struktur zespołów ceramicznych. In Problemy chronologii ceramiki wczesnośredniowiecznej na Pomorzu Zachodnim; Wydawnictwo PKZ: Warszawa, Poland, 1986; pp. 62–117. [Google Scholar]

- Filipowiak, W.; Gundlach, H. Wolin Vineta: Die Tatsächliche Legende Vom Untergang Und Aufstieg der Stadt; Hinstorff: Rostock, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Filipowiak, W.; Zdzienicka, M. Wolin-die Entwicklung des Seehandelszentrums im 8.-12. Jh. Slavia Antiq. Czas. Poświęcone Starożytnościom Słowiańskim 1995, 36, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Filipowiak, W. Some aspects of the development of Wolin in the 8th-11th centuries in the light of the results of new research. In Polish Lands at the Turn of the First and the Second Millennia; Urbańczyk, P., Ed.; Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; pp. 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ważny, T.; Eckstein, D. Dendrochronologiczne datowanie wczesnośredniowiecznej słowiańskiej osady Wolin. Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 1987, 33, 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sindbæk, S.M. Viking, Age Wolin and the Baltic Sea trade. Proposals, declines and engagements. In Across The Western Baltic: Proceeding From an Archaeological Conference in Vordingborg; Keld, M.H., Kristoffer, B.P., Eds.; Sydsjællands Museum: Vordingborg, Denmark, 2006; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Filipowiak, W. Der Götzentempel von Wollin. Kult und Magie. In Beiträge zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Przemysław Urbańczyk ed.; Institute of Archeology and Ethnology. Polish Academy of Sciences: Berlin, Germany, 1982; Beiheft 17; pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Barański, M.K. Dynastia Piastów w Polsce; PWN: Poznań, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzewski, A.; Kolander, R.; Szpikowski, J. Zintegrowany monitoring środowiska przyrodniczego. In Raport o Stanie Środowiska w Województwie Zachodniopomorskim w Latach 2006–2007; Wojewódzki Inspektorat Ochrony Środowiska w Szczecinie: Szczecin, Poland, 2008; Volume XI, pp. 198–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kubasiewicz, M. Szczątki zwierząt wczesnośredniowiecznych z Wolina, Szczecin. Szczecińskie Wydaw. Nauk. 1959, II, 5–151. [Google Scholar]

- Świeżyński, K. Analiza szczątków kostnych z grobu psa ze stanowiska Łęczyca-Dzierzbiętów. Acta Archaeol. Univ. Lodz. 1956, 4, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wyrost, P.; Kucharczyk, J. Versuchder Bestimmung der Widerristhöhe des Hundes mittels der inneren Hirnhöhlenlange. Acta Theriol. 1967, XII, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlikowski, J.; Stępień, J. Zwierzęta we wczesnośredniowiecznym Wolinie. Badania archeozoologiczne. In Wolin Wczesnośredniowieczny; Stanisławski, B., Filipowiak, W., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 82–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kubasiewicz, M.; Gawlikowski, J. Szczątki zwierzęce z Wolina-Miasta (stanowisko wykopaliskowe nr 5). Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 1963, 9, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kubasiewicz, M.; Gawlikowski, J. Szczątki zwierzęce z wczesnośredniowiecznego grodu w Kołobrzegu. Szczecińskie Tow. Nauk. XXIV 1965, 2, 5–103. [Google Scholar]

- Gawlikowski, J.; Stępień, J. Struktura spożycia mięsa we wczesnośredniowiecznym Wolinie. In Instantia Est Mater Doctrinae; Wilgocki, E., Dworaczyk, M., Kowalski, K., Porzeziński, A., Słowiński, S., Eds.; Stowarzyszenie Naukowe Archeologów Polskich (The Scientific Association of Polish Archaeologists): Szczecin, Poland, 2001; pp. 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Michczyński, A.; Rębkowski, M. Chronology of the cultural deposits. In Wolin—The Old Town I, Settlement Structure, Stratigraphy, Chronology; Rębkowski, M., Ed.; Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Szczecin, Poland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stępień, J.; Gawlikowski, J. Zwierzęta dziko żyjące na Pomorzu Zachodnim we wczesnym średniowieczu. Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 2016, XII, 427–447. [Google Scholar]

- Chełkowski, Z.; Filipiak, J.; Chełkowska, B. Występowanie i charakterystyka ichtiofauny we wczesno-średniowiecznych warstwach osadniczych portu w Wolinie. [Occurrence and description of fish remains in early medieval settlement layers of the port of Wolin.]. Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 1998, 44, 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Pazdur, M.F.; Awasiuk, R.; Goslar, T.; Pazdur, A. Chronologia radiowęglowa początków osadnictwa w Wolinie i żeglugi u ujścia Odry. In Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Śląskiej, Seria: Matematyka-Fizyka; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 1994; z.70, Geochronometria, 9; pp. 124–195. [Google Scholar]

- Habermehl, K.H. Die Alterbestimmung bei Haus-Und Labortieren; Verlag Paul Parey: Berlin, Germany; Hamburg, Germany, 1975; pp. 168–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lutnicki, W. Uzębienie Zwierząt Domowych; PWN: Warszawa, Poland; Kraków, Poland, 1972; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- The, T.L.; Trouth, C.O. Sexual dimorphism in the basilar part of the occipital bone of the dog (Canis familiaris). Acta Anat. 1976, 95, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trouth, C.O.; Winter, S.; Gupta, K.C.; Millis, R.M.; Holloway, J.A. Analysis of the sexual dimorphism in the basioccipital portion of the dog’s skull. Acta Anat. 1977, 98, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brothwell, D.; Malaga, A.; Burleigh, R. Studies on amerindian dogs, 2: Variation in early peruvian dogs. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1979, 6, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesch von den, A. A Guide to the Measurement of Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites; Peabody Museum Bulletin 1; Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lasota-Moskalewska, A. Podstawy archeozoologii. Szczątki ssaków. In Obliczanie Wysokości w Kłębie; Wydaw. Nauk. PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chrószcz, A.; Janeczek, M.; Onar, V.; Staniorowski, P.; Pospieszny, N. The shoulder heigh estimation in dogs based on the internal dimension of cranial cavity using mathematical formula. Anat. Histol Embryol 2007, 36, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wustinger, J.; Galli, J.; Rozpędek, W. An osteometric study on recent roe deer (Capreolus capreolus L. 1758). Folia Morphol. 2005, 64, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Chrószcz, A.; Baranowski, P.; Janowski, A.; Poradowski, D.; Janeczek, M.; Onar, V.; Sudoł, B.; Spychalski, P.; Dudek, A.; Sienkiewicz, W.; et al. Withers height estimation in medieval horse samples from Poland: Comparing the internal cranial cavity-based modified Wyrost and Kucharczyk method with existing methods. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2022, 32, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G. Osteology of the Kuri Maori: The Prehistoric Dog of New Zealand. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997, 24, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, P.; Wróblewska, M.; Wojtas, J. Morphology and morphometry of the nuchal plane of breeding chinchilla (Chunchilla laniger, Molina 1782) skulls allowing for sex and litter size at birth. Bull. Vet. Inst. Pulawy 2009, 53, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Brassard, C.; Callou, C. Sex determination of archaeological dogs using the skull: Evaluation of morphological and metric traits on various modern breeds. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 31, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysiak, K. Anatomia zwierząt; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1975; T1; pp. 307–309. [Google Scholar]

- Farke, D.; Staszyk, C.; Failing, K.; Kirberger, R.M.; Schmidt, M.J. Sensitivity and specificity of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography for the determination of the developmental state of cranial sutures and synchondroses in dog. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, A.; Foley, L.; Weisbecker, V. Patterns and implications of extensive heterochrony in carnivoran cranial suture closure. J. Evol. Biol. 2013, 26, 1294–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, M.; Haussman, S. Cranial suture closure in domestic dog breeds and its relationships to skull morphology. Anat. Rec. 2016, 299, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.R.; Brothwell, D. Animal Diseases in Archaeology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Wyrost, P. Badania nad typami psów wczesnośredniowiecznego Opola i Wrocławia. Sil. Antiq. 1963, 5, 198–223. [Google Scholar]

- de Mazzorin, J.G.; Tagliacozzo, A. Morphological and osteological changes in the dog from the Neolithic to the Roman period in Italy. In Dogs Through Time: An Archaeological Perspective; Archaeopress: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000; pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, C. Domestic dog skeletons at Valsgarde cemetery, Uppland, Sweden: Quantification and morphological reconstruction. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 36, 102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räber, H. Encyklopedia Psów Rasowych; Multico Oficyna Wydawnicza: Warszawa, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Przeczek, I.; Wacławik, R.; Falęcka, A. Szpice i Psy w Typie Pierwotnym; Wydawnictwo Paweł Przeczek: Bielsko-Biała, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gawlikowski, J. Zwierzęcy materiał wykopaliskowy z zamku w Dobrej Nowogardzkiej, woj. Szczecińskie. Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 1996, XL, 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kubasiewicz, M.; Gawlikowski, J. Zwierzęcy materiał kostny z wczesnośredniowiecznego Rynku Warzywnego w Szczecinie. Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 1969, 15, 189–241. [Google Scholar]

- Stępień, J. Szczątki kostne zwierząt z wczesnośredniowiecznego grodu w Mścięcinie. Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 1993, 39, 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Gawlikowski, J. Zwierzęce szczątki kostne z wczesnośredniowiecznego podgrodzia w Stargardzie Szczecińskim. Mater. Zachodniopomorskie 1997, 42, 139–186. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, H.-H. Zur Kenntnis der Haustiere aus der Vőlkerwannderungszeit im Mittelelbe—Saale-Gebiet. ZfA–Z. Archäol. 1980, 14, 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Reichstein, H. Untersuchung an mittelalterlichen Tierknochen aus Bardowick Kr. Lüneburg. Hambg. Beiträge Zur Archäologie 1983, 10, 227–281. [Google Scholar]

- Teichert, L. Die Tieknochenfunde von der slawischen Burg und Siedlung auf der Dominsel Brandenburg/Havel (Säugetiere, Vőgel und Muscheln). Verőffentlichungen Des Mus. Für Ur—Und Frühgeschichte Potsdam Bd. 1988, 22, 143–219. [Google Scholar]

- Bergström, A.; Frantz, L.; Schmidt, R.; Ersmark, E.; Lebrasseur, O.; Girdland-Flink, L.; Lin, A.T.; Storå, J.; Sjögren, K.G.; Anthony, D.; et al. Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs. Science 2020, 370, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granado, J.; Susat, J.; Gerling, C.; Schernig-Mráz, M.; Schlumbaum, A.; Deschler-Erb, S.; Krause-Kyora, B. A melting pot of Roman dogs north of the Alps with high phenotypic and genetic diversity and similar diets. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipowiak, W. Wyspa Wolin w prahistorii i we wczesnym średniowieczu. In Z Dziejów Ziemi Wolińskiej; Instytut Zachodniopomorski w Szczecinie: Szczecin, Poland, 1973; pp. 31–137. [Google Scholar]

- Filipowiak, W. Die Bedeutung Wollins im Ostseehandel. Acta Visbyensia 1985, VII, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Andersone, Ž.; Lucchini, V.; Randi, E.; Ozoliņš, J. Hybridisation between wolves and dogs in Latvia as documented using mitochondrial and microsatellite DNA markers. Mamm. Biol. 2002, 67, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindrikson, M.; Mannil, P.; Ozolins, J.; Krzywinski, A.; Saarma, U. Bucking the Trend in Wolf-Dog Hybridization: First Evidence from Europe of Hybridization between Female Dogs and Male Wolves. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hourani, Y. Persian Period dog burials of Beirut: Morphology, health, mortality and mortuary practices. In Archaeozoology of the Near East XII, Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium of the ICAZ Archaeozoology of Southwest Asia and Adjacent Areas Working Group, Groningen Institute of Archaeology, Groningen, The Netherlands, 14–15 June 2015; Barkhuis: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 153–184. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, H.E. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog, 3rd ed.; W.B. Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993; Chapter 4; pp. 122–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sisson, S.; Grossman, J.D. The Anatomy of Domestic Animals; W.B. Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Dating | Cranial Skeleton | Postcranial Skeleton | In Total | % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | M | S | H | R | U | F | T | ||||

| 1. | The end of the 8th century to the year 850 | 3 | 3 | 1.44 | |||||||

| 2. | The second half of the 9th century AD | 4 | 4 | 1.92 | |||||||

| 3. | From the second half of the 9th century to the turn of the 9th to 10th centuries AD | 7 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 33 | 15.86 | ||

| 4. | From the end of the 9th century to around the middle of the 10th century AD | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 5.77 | ||||

| 5. | From the middle of the 10th century to the end of the 3rd quarter of the 10th century AD | 1 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 35 | 16.83 | |

| 6. | The turn of the 10th to 11th centuries or the first half of the 11th century AD | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 28 | 13.46 | |

| 7. | From the middle of the 11th century to the beginning of the 2nd half of the 11th century AD (1000–1050) | 3 | 5 | 7 | 15 | 7.22 | |||||

| 8. | The second half of the 11th century AD (1050–1100) | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 17 | 8.17 | |||

| 9. | From the end of the 11th century to the second half of the 12th century AD | 10 | 3 | 13 | 6.25 | ||||||

| 10. | The second half of the 12th century (1100–1150) to the beginning of the 13th century AD | 4 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 48 | 23.08 |

| In total | 13 | 47 | 21 | 33 | 34 | 17 | 16 | 27 | 208 | 100 | |

| Index | Sex | Century | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8–13th AD | 21st AD | ||||||

| n | x ± s | Min–Max | n | x ± s | Min–Max | ||

| B * 100/L [90] | male | 9 | 103.69 ± 11.79 | 82.31–116.58 | 9 | 101.79 ± 18.42 | 74.57–132.82 |

| female | 4 | 143.78 ± 5.51 | 139.14–150.88 | 4 | 148.25 ± 9.09 | 137.18–157.92 | |

| Osteometrics (mm). | n | x ± s | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total length | 8 | 197.25 ± 14.95 | 182.00 | 223.00 |

| 2 | Condylobasal length | 8 | 184.44 ± 14.17 | 171.00 | 209.00 |

| 3 | Basal length | 8 | 174.56 ± 19.49 | 162.00 | 192.00 |

| 4 | Basicranial axis | 12 | 47.44 ± 13.62 | 42.71 | 54.74 |

| 5 | Basifacial axis | 8 | 127.38 ± 9.81 | 115.75 | 144.16 |

| 6 | Neurocranium length | 10 | 104.40 ± 6.45 | 98.00 | 115.00 |

| 7 | Upper neurocranium length | 12 | 92.36 ± 8.06 | 79.89 | 109.04 |

| 8 | Viscerocranium length | 8 | 98.44 ± 9.46 | 89.88 | 116.83 |

| 9 | Facial length | 8 | 113.85 ± 9.38 | 103.48 | 129.30 |

| 10 | Greatest length of the nasals | 8 | 78.05 ± 7.56 | 72.74 | 93.26 |

| 11 | Length of braincase (Basion–Ethmoideum) | 13 | 83.44 ± 5.62 | 75.65 | 96.22 |

| 12 | Snout length | 8 | 89.56 ± 6.78 | 81.98 | 171.88 |

| 13 | Median palate length | 8 | 96.98 ± 7.02 | 89.64 | 107.51 |

| 13a | Palatal length | 8 | 94.69 ± 6.07 | 88.33 | 103.45 |

| 14 | Length of the horizontal part of the palatine | 9 | 33.99 ± 3.11 | 29.04 | 38.12 |

| 15 | Length of the cheektooth row | 10 | 68.82 ± 4.03 | 62.70 | 75.63 |

| 16 | Length of the molar row | 10 | 21.02 ± 1.57 | 18.95 | 23.36 |

| 17 | Length of the premolar row | 10 | 53.15 ± 3.33 | 48.03 | 60.37 |

| 19 | Length of the carnassial alveolus | 10 | 18.01 ± 0.63 | 16.89 | 18.66 |

| 19a | Length of P4 | 10 | 18.14 ± 0.50 | 17.13 | 18.90 |

| 19b | Greatest breadth of P4 | 10 | 9.79 ± 1.30 | 7.24 | 11.74 |

| 19c | Breadth of P4 | 10 | 6.62 ± 1.02 | 5.29 | 8.26 |

| 20 | Length of M1 | 7 | 12.94 ± 0.86 | 11.77 | 14.03 |

| 20a | Breadth of M1 | 7 | 16.67 ± 0.80 | 15.33 | 17.87 |

| 21 | Length of M2 | 8 | 7.30 ± 0.46 | 6.74 | 8.01 |

| 21a | Breadth of M2 | 8 | 10.39 ± 0.54 | 9.72 | 11.40 |

| 22 | Greatest diameter of auditory bulla | 12 | 22.45 ± 2.95 | 19.00 | 27.06 |

| 23 | Greatest mastoid breadth | 11 | 65.59 ± 4.20 | 60.00 | 74.00 |

| 24 | Breadth dorsal to the external auditory meatus | 12 | 63.33 ± 4.77 | 56.45 | 72.72 |

| 25 | Greatest breadth of the occipital condyles | 13 | 36.75 ± 2.42 | 34.43 | 43.04 |

| 26 | Greatest breadth of the bases of the paraoccipital processes | 11 | 53.16 ± 5.61 | 46.28 | 62.68 |

| 27 | Greatest breadth of the foramen magnum | 12 | 18.56 ± 1.10 | 16.77 | 20.44 |

| 28 | Height of the foramen magnum | 13 | 16.24 ± 1.80 | 12.95 | 19.36 |

| 29 | Greatest breadth of the braincase | 13 | 56.85 ± 3.26 | 50.80 | 62.00 |

| 30 | Zygomatic breadth | 8 | 105.36 ± 9.12 | 90.60 | 121.82 |

| 31 | Least breadth of the skull | 13 | 38.45 ± 3.24 | 32.75 | 45.36 |

| 32 | Frontal breadth | 13 | 50.97 ± 7.28 | 42.07 | 68.01 |

| 33 | Least breadth between orbits | 10 | 39.68 ± 5.93 | 32.66 | 50.04 |

| 34 | Greatest palatal breadth | 9 | 61.70 ± 4.35 | 56.66 | 69.95 |

| 35 | Least palatal breadth | 9 | 34.05 ± 3.01 | 30.37 | 39.37 |

| 36 | Breadth at the canine alveoli | 7 | 35.41 ± 3.51 | 31.85 | 41.04 |

| 37 | Greatest inner high of the orbit | 10 | 31.67 ± 3.24 | 26.47 | 36.96 |

| 38 | Skull height | 13 | 53.17 ± 5.49 | 46.05 | 65.07 |

| 39 | Skull height without the sagittal crest | 13 | 46.19 ± 3.04 | 41.73 | 51.77 |

| 40 | Height at the occipital triangle | 13 | 40.87 ± 3.24 | 36.52 | 47.03 |

| 41 | Height of the canine | 5 | 15.19 ± 6.42 | 9.41 | 24.26 |

| 42 ♠ | Neurocranium capacity | 8 | 40.59 ± 7.37 | 32.72 | 51.63 |

| 43 * | Maxillofacial width | 10 | 52.53 ± 6.88 | 42.17 | 64.56 |

| 44 * | Zygomatic length | 12 | 95.71 ± 7.57 | 83.99 | 107.74 |

| 45 * | Foramen magnum area | 12 | 198.53 ± 31.02 | 150.21 | 261.52 |

| 46 * | Occipital triangle area | 11 | 1093.35 ± 144.26 | 905.93 | 1384.26 |

| Index | Statistical Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | x ± s | Min | Max | |

| Zy–Zy × 100/A–P | 7 | 53.15 ± 2.90 | 48.76 | 58.16 |

| Eu–Eu × 100/A–N | 8 | 58.74 ± 3.85 | 54.75 | 64.88 |

| Zy–Zy × 100/N–P | 7 | 106.49 ± 8.54 | 95.13 | 117.78 |

| Eu–Eu × 100/A–P | 8 | 29.43 ± 1.68 | 27.80 | 32.48 |

| Eu–Eu × 100/B–P | 8 | 33.24 ± 1.90 | 31.01 | 36.48 |

| Eu–Eu × 100/B–P | 8 | 31.49 ± 2.16 | 29.16 | 34.88 |

| N–B × 100/B–P | 7 | 60.18 ± 1.66 | 57.99 | 62.50 |

| Pm–Pd × 100/St–P | 8 | 54.82 ± 3.04 | 49.94 | 58.74 |

| (A–N) × (Eu–Eu) × (CH) | 8 | 40.59 ± 7.37 | 32.77 | 51.63 |

| B–S × 100/P–S | 8 | 37.71 ± 2.74 | 33.66 | 43.29 |

| Ect–Ect × 100/A–P | 8 | 29.93 ± 2.14 | 24.43 | 30.50 |

| N–A × 100/N–P | 8 | 100.72 ± 5.72 | 90.87 | 107.93 |

| Eu–Eu × 100/F(So)–O | 12 | 61.51 ± 4.86 | 53.40 | 71.23 |

| Palatal width × 100/Palatal length | 8 | 63.83 ± 2.64 | 59.31 | 66.97 |

| Canine width/Palatal length | 7 | 36.92 ± 2.24 | 32.98 | 38.88 |

| Area Foramen magnum/Area of occipital triangle | 10 | 18.21 ± 2.54 | 15.44 | 22.77 |

| Area of occipital triangle/Ot–Ot | 11 | 16.63 ± 1.51 | 14.02 | 18.71 |

| B–P/Area of occipital triangle | 8 | 16.09 ± 1.67 | 13.87 | 18.27 |

| P1–M2/A–P | 8 | 35.10 ± 1.69 | 33.60 | 38.36 |

| Wyrost–Kucharczyk Coefficient = (1.016 × B–E) − 31.2 | 13 | 53.58 ± 5.72 | 45.66 | 66.56 |

| ♠ (Maxillofacial width)2/B–P | 8 | 15.93 ± 3.74 | 11.29 | 21.71 |

| Forehead Width Index Ect–Ect/B–P | 8 | 30.44 ± 2.84 | 27.61 | 35.42 |

| Exponential Forehead Width Index (Ect–Ect)2/B–P | 8 | 16.44 ± 4.23 | 12.89 | 24.09 |

| Projected Viscerocranial Length (P–Ect) × 100/B–P | 8 | 65.90 ± 1.25 | 63.36 | 67.45 |

| Orbital Position Index (P–Ect × 100/A–Ect) | 8 | 121.28 ± 3.98 | 116.13 | 128.46 |

| Braincase Length Index (A–Ect) × 100/B–P | 8 | 54.38 ± 1.85 | 52.06 | 56.52 |

| ♥ Forehead Position Index P–So × 100/So–O | 8 | 120.47 ± 8.83 | 104.25 | 129.92 |

| Tooth Length Index P1–M2/B–P | 8 | 39.15 ± 0.96 | 37.73 | 40.76 |

| Exponential Tooth Length Index (P1–M2)2/B–P | 8 | 26.77 ± 2.08 | 23.49 | 29.83 |

| ♦ Index Zygomatic Arch Length/A–Zy | 9 | 1.13 ± 0.07 | 1.02 | 1.25 |

| Index Facial Skull Length N–Rh/N–P | 5 | 0.70 ± 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.78 |

| Index1 Eu–Eu/N–Rh | 8 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.82 |

| Index ‘1 Eu–Eu/N–P | 8 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.66 |

| Index2 P–A/Zy–Zy | 7 | 1.89 ± 0.14 | 1.72 | 2.05 |

| Index ‘2 P–B/Zy–Zy | 7 | 1.97 ± 0.13 | 1.53 | 1.85 |

| Index3 A–N/Zy–Zy | 7 | 0.95 ± 0.08 | 0.87 | 1.05 |

| Index4 A–N/Eu–Eu | 8 | 1.71 ± 0.11 | 1.54 | 1.83 |

| Osteometrics (mm) | Statistical Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | x ± s | Min | Max | ||

| Measurements of the mandible | |||||

| 1 | Total length | 21 | 136.20 ± 11.08 | 113.50 | 150.00 |

| 2 | Length: the angular process | 12 | 140.39 ± 6.90 | 128.00 | 149.60 |

| 3 | Length from the indentation between the condyle process and the angular process | 19 | 131.84 ± 8.90 | 113.00 | 143.00 |

| 4 | Length: the condyle process–the aboral border of the canine alveolus | 25 | 121.05 ± 10.19 | 97.80 | 133.00 |

| 5 | Length from the indentation between the condyle process angular process–the aboral border of the canine alveolus | 23 | 116.30 ± 8.16 | 97.10 | 126.70 |

| 6 | Length: the angular process–the aboral border of the canine alveolus | 13 | 124.96 ± 6.83 | 112.50 | 134.20 |

| 7 | Length: the aboral border of the alveolus of M3–the aboral of the canine alveolus | 29 | 76.92 ± 8.90 | 52.40 | 86.70 |

| 8 | Length of the cheektooth row, M3-P1 * | 27 | 71.77 ± 8.35 | 49.10 | 83.20 |

| 9 | Length of the cheektooth row, M3-P2 * | 27 | 68.80 ± 5.09 | 58.20 | 77.50 |

| 10 | Length of the molar row | 31 | 34.46 ± 3.50 | 25.10 | 38.80 |

| 11 | Length of the premolar row, P1–P4 | 28 | 39.79 ± 3.13 | 33.60 | 45.00 |

| 12 | Length of the premolar row, P2–P4 | 30 | 34.66 ± 2.72 | 28.70 | 39.30 |

| 13 | Length of the carnassial | 24 | 21.15 ± 1.54 | 16.50 | 23.50 |

| 13a | Breadth of the carnassial | 24 | 8.85 ± 0.65 | 7.40 | 10.00 |

| 14 | Length of the carnassial alveolus | 32 | 20.09 ± 1.84 | 15.80 | 22.80 |

| 15 | Length of M2 | 17 | 8.61 ± 0.99 | 6.00 | 10.00 |

| 15a | Breadth of M2 | 17 | 6.49 ± 0.71 | 4.90 | 7.70 |

| 16 | Length of M3 and breadth of M3 | teeth absent | |||

| 17 | Greatest thickness of the body of the jaw | 31 | 11.02 ± 1.17 | 8.20 | 13.30 |

| 18 | Height of the vertical ramus: basal point of the angular process | 13 | 54.68 ± 2.94 | 50.00 | 59.50 |

| 19 | Height of the mandible behind M1 | 31 | 22.57 ± 2.48 | 15.50 | 27.20 |

| 20 | Height of the mandible behind P2 and P3 | 32 | 18.55 ± 1.78 | 12.80 | 21.30 |

| 21 | Height of the canine | 10 | 19.97 ± 8.82 | 9.77 | 42.00 |

| Index | Statistical Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | x ± s | Min | Max | |

| Height of the vertical ramus * 100/total length | 12 | 38.89 ± 1.95 | 34.97 | 42.22 |

| Height of the mandible behind M1 * 100/total length | 21 | 16.64 ± 0.92 | 15.10 | 18.44 |

| Height of the vertical ramus * 100/length of the cheektooth row M3-P1 | 11 | 73.77 ± 3.71 | 65.53 | 78.44 |

| Height of the mandible behind M1 * 100/length of the molar row | 29 | 64.85 ± 3.70 | 59.21 | 74.32 |

| Greatest thickness of the body of jaw * 100/total length | 21 | 8.08 ± 0.57 | 6.94 | 9.38 |

| Greatest thickness of the body of jaw * 100/height of the mandible behind M1 | 29 | 49.03 ± 3.36 | 41.20 | 55.75 |

| Osteometrics (mm) | n | x ± s | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scapula | ||||

| Height | 5 | 126.94 ± 20.05 | 92.70 | 144.00 |

| Diagonal height | 1 | 129.79 | - | - |

| Greatest dorsal length | 1 | 67.62 | - | - |

| Smallest length of the neck of the scapula | 19 | 24.88 ± 3.69 | 13.90 | 30.05 |

| Greatest length of the glenoid process | 19 | 30.36 ± 3.97 | 18.70 | 37.40 |

| Length of the glenoid cavity | 18 | 27.72 ± 3.35 | 17.20 | 30.00 |

| Breadth of the glenoid cavity | 16 | 17.95 ± 1.78 | 14.00 | 20.50 |

| Humerus | ||||

| Greatest length | 15 | 152.31 ± 28.33 | 100.00 | 188.80 |

| Greatest length from the head (caput | 13 | 150.29 ± 25.87 | 97.20 | 181.30 |

| Greatest depth of the proximal end | 14 | 29.00 ± 5.86 | 19.60 | 39.40 |

| Depth of the proximal end | 14 | 38.46 ± 6.62 | 27.20 | 47.00 |

| Smallest breadth of the diaphysis | 29 | 12.64 ± 1.76 | 8.80 | 15.50 |

| Greatest breadth of the distal end | 30 | 31.50 ± 4.23 | 21.70 | 37.60 |

| Greatest breadth of the trochlea | 28 | 22.65 ± 3.55 | 14.80 | 33.68 |

| Circumference of the humerus measured at a distance of 35% from the distal end of its diaphysis | 28 | 41.17 ± 5.60 | 27.50 | 52.00 |

| Radius | ||||

| Greatest length | 19 | 146.31 ± 37.40 | 92.50 | 203.00 |

| Greatest breadth of the proximal end | 32 | 17.57 ± 1.90 | 12.80 | 21.50 |

| Smallest breadth of the diaphysis | 31 | 12.83 ± 1.73 | 9.00 | 15.40 |

| Smallest circumference of the diaphysis | 31 | 34.07 ± 4.01 | 25.50 | 40.50 |

| Breadth of the distal end | 20 | 23.25 ± 3.90 | 12.60 | 28.00 |

| Ulna | ||||

| Greatest length | 12 | 146.34 ± 34.56 | 96.30 | 221.00 |

| Depth across the processus anconaeus | 17 | 23.05 ± 4.09 | 15.80 | 29.08 |

| Smallest depth of the olecranon | 17 | 19.42 ± 4.03 | 11.80 | 26.89 |

| Greatest breadth across the coronoid process | 17 | 15.30 ± 2.28 | 11.50 | 19.20 |

| Femur | ||||

| Greatest length | 13 | 165.01 ± 36.07 | 99.00 | 214.00 |

| Greatest length from the caput femoris | 10 | 162.07 ± 43.23 | 93.50 | 214.00 |

| Greatest breadth of the proximal end | 14 | 36.59 ± 5.92 | 25.00 | 44.03 |

| Greatest depth of the caput femoris | 16 | 18.00 ± 2.76 | 12.10 | 20.80 |

| Smallest breadth of the diaphysis | 16 | 12.33 ± 1.38 | 9.40 | 14.40 |

| Femoral circumference taken at the midpoint on the long axis | 16 | 40.30 ± 5.41 | 28.00 | 47.50 |

| Greatest breadth of the distal end | 12 | 31.15 ± 5.64 | 21.80 | 41.70 |

| Tibia | ||||

| Greatest length | 21 | 158.93 ± 36.68 | 93.00 | 210.00 |

| Greatest breadth of the proximal end | 15 | 32.51 ± 5.38 | 23.60 | 42.70 |

| Smallest breadth of the diaphysis | 24 | 12.38 ± 1.73 | 8.60 | 15.00 |

| Greatest breadth of the distal end | 20 | 21.31 ± 3.21 | 15.20 | 27.20 |

| Bone | Early Medieval Archeological Site in the Polish Part of Pomerania | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolin, Current Research | Kołobrzeg Kołobrzeg [81] | Dobra Nowogardzka [110] | Szczecin- Vegetable Market Szczecin [111] | |

| Scapula | 37.63–58.46 | - | 45.18 | 38.16–56.00 |

| Humerus | 31.64–63.62 | 47.42–50.88 | – | – |

| Radius | 29.78–65.50 | 37.99–39.47 | 30.0–54.0 | 62.76–65.04 |

| Femur | 29.79–65.90 | - | 57.5 | 61.40–62.84 |

| Tibia | 27.15–61.32 | - | 29.4 | 61.90–62.84 |

| Skull Number | (1) Zy–Zy/A–P × 100 | (2) N–A/N–P | (3) Eu–Eu/N–A × 100 | Skull Type per [123] | Dating (See Table 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A954 | 48.76 | 1.05 | 54.75 | d | 1 |

| 2947 A955 | 55.26 | 0.94 | 64.88 | s-m | 1 |

| 2572 A954 | 56.66 | 0.99 | 57.84 | s-m | 1 |

| 2948 | - | - | - | - | 5 |

| 437 | 49.84 | 0.91 | 58.40 | d | 7 |

| 439 | - | - | - | - | 7 |

| 2768 A955 | - | - | - | - | 7 |

| 829.830 | 48.97 | 1.03 | 56.32 | d | 8 |

| 831 | 54.40 | 1.08 | 55.04 | s-d | 8 |

| 2493 A955 | 58.16 | 1.02 | 64.18 | s-m | 10 |

| 2704 A995 | - | 1.03 | 58.49 | d (3) | 10 |

| 2490 | - | - | - | - | 10 |

| 2595 | - | - | - | - | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baranowski, P. Morphological and Metric Analysis of Medieval Dog Remains from Wolin, Poland. Animals 2025, 15, 2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152171

Baranowski P. Morphological and Metric Analysis of Medieval Dog Remains from Wolin, Poland. Animals. 2025; 15(15):2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152171

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaranowski, Piotr. 2025. "Morphological and Metric Analysis of Medieval Dog Remains from Wolin, Poland" Animals 15, no. 15: 2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152171

APA StyleBaranowski, P. (2025). Morphological and Metric Analysis of Medieval Dog Remains from Wolin, Poland. Animals, 15(15), 2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152171