Comprehensive Evaluation and Future Perspectives of Non-Surgical Contraceptive Methods in Female Cats and Dogs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- English articles about non-surgical spaying based on biotechnology;

- Studies in vivo involving female canines or felines.

3. Results

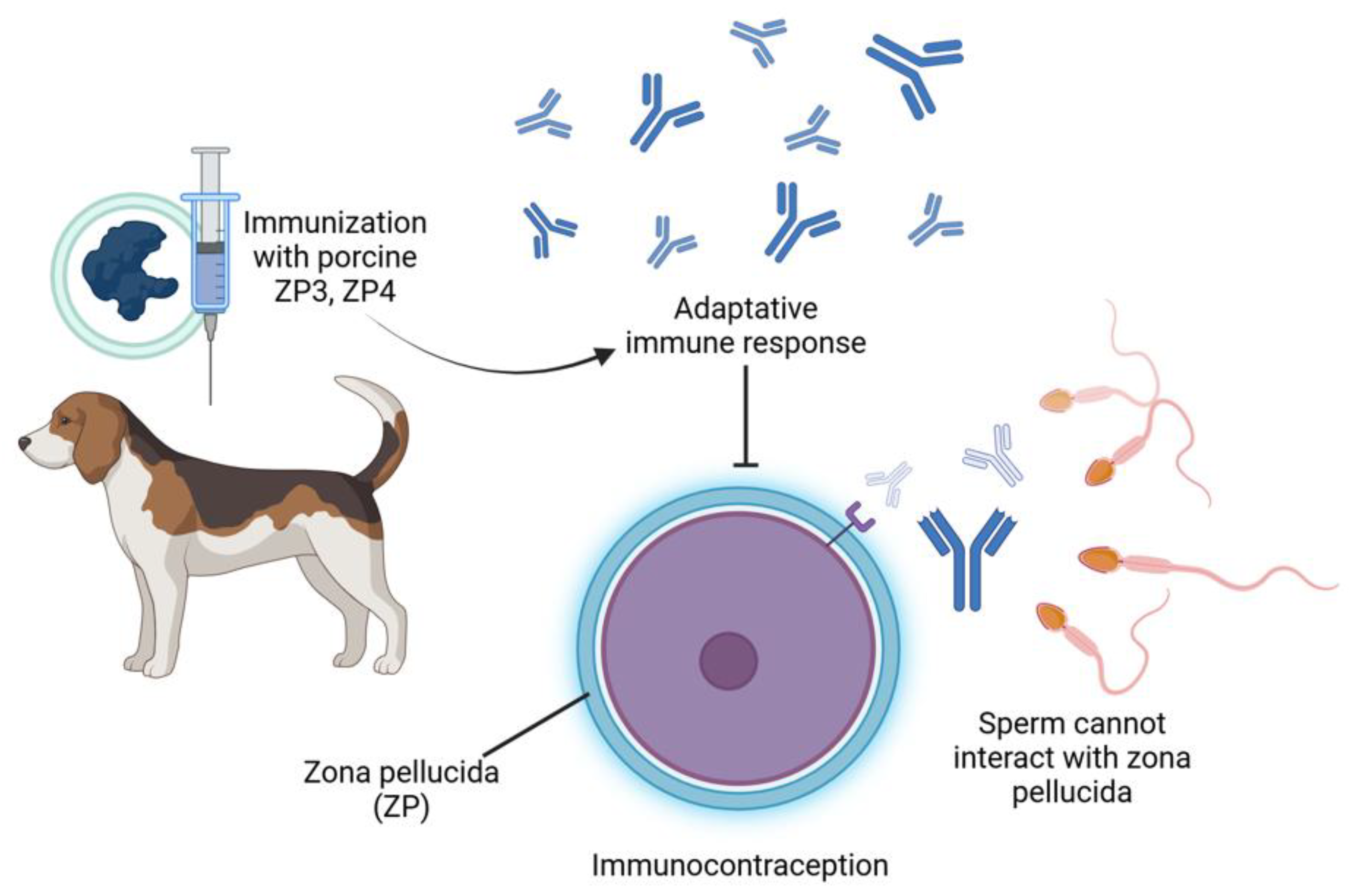

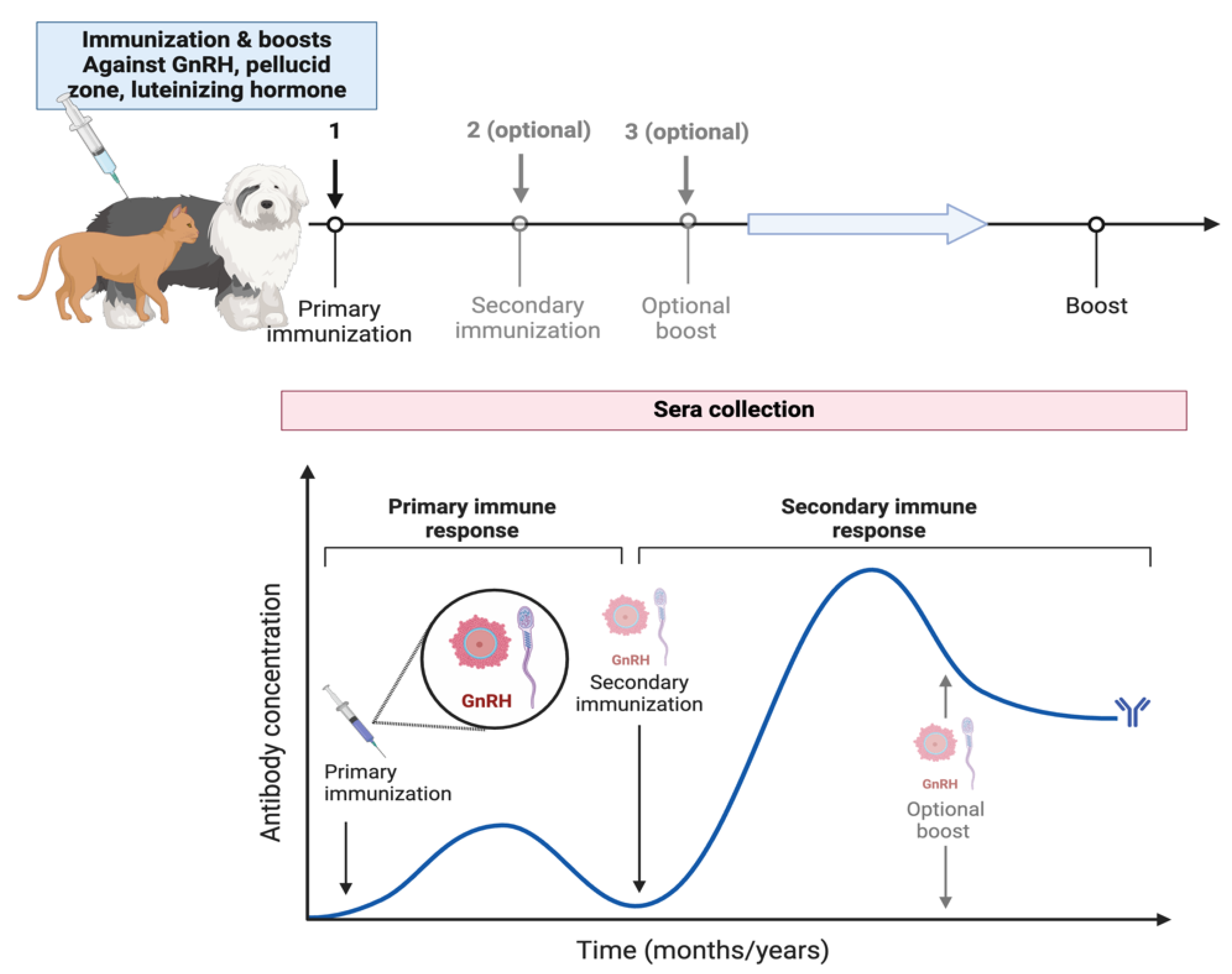

3.1. Immunocontraception

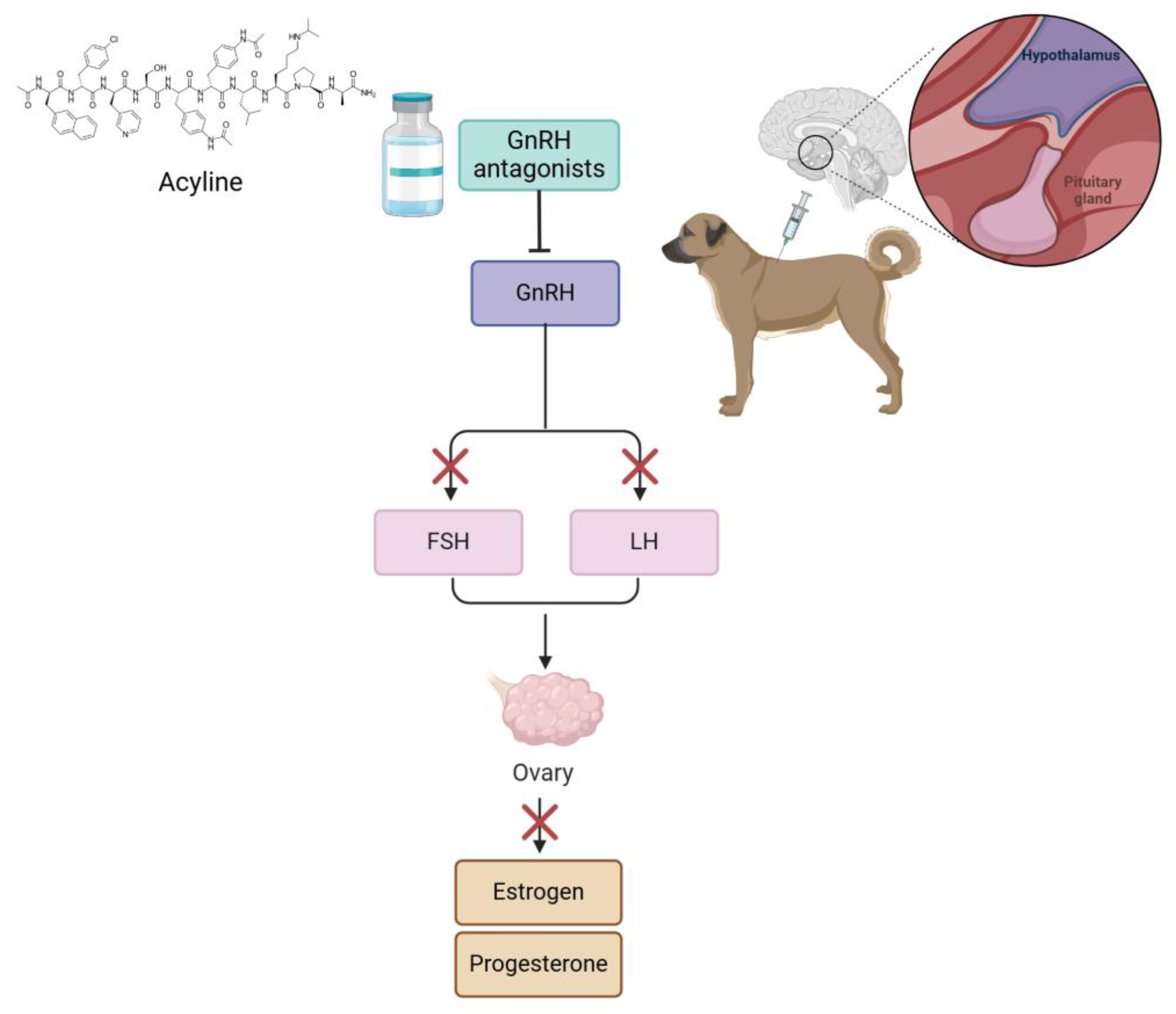

3.2. Hormone Analogs

3.3. Use of Modulators of Corpus Luteum (CL) as Contraceptive Methods in Bitches

3.4. Kisspeptin (KP)

3.5. Other Contraception Methods

4. Final Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAV | adeno-associated virus |

| ALHS | anti-LH serum |

| Al(OH)3 | aluminum hydroxide |

| b.w. | body weight |

| CL | corpus luteum |

| cZP | crude porcine zona pellucida |

| CP | complete Freund’s adjuvant |

| CP-20 | CP-20 adjuvant |

| DA | deslorelin acetate |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| E2 | estradiol |

| eCG | equine chorionic gonadotropin |

| FSH | follicle-stimulating hormone |

| GnRH | gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| hCG | human chorionic gonadotropin |

| IgG | immunoglobulin G |

| i.m. | intramuscular |

| i.v. | intravenous |

| KLH | keyhole limpet hemocyanin |

| KP-10 | kisspeptin-10 |

| LH | luteinizing hormone |

| LH-R | luteinizing hormone receptor |

| LH-RH | luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone |

| MA | megestrol acetate |

| MAL | luteal Hhrmone |

| mL | milliliters |

| NaCl | sodium chloride |

| P4 | progesterone |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| pZP | porcine zona pellucida |

| SIZP | soluble isolated zona pellucida |

| s.c. | subcutaneous |

| STAR | steroidogenic acute regulatory protein |

| TT-KK-pZP3 | promiscuous T cell epitope of tetanus toxoid conjugated with pZP3 |

| ZP | zona pellucida |

References

- Vansandt, L.M.; Meinsohn, M.C.; Godin, P.; Nagykery, N.; Sicher, N.; Kano, M.; Kashiwagi, A.; Chauvin, M.; Saatcioglu, H.D.; Barnes, J.L.; et al. Durable contraception in the female domestic cat using viral-vectored delivery of a feline anti-Müllerian hormone transgene. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, B.B.; Clavio, A.; Singh, M.; Rathnam, P.; Bukharovich, E.Y.; Reimers, T.J.; Saxena, A.; Perkins, S. Effect of immunization with bovine luteinizing hormone receptor on ovarian function in cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2003, 64, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Roldan, J.A.; Otranto, D. Zoonotic parasites associated with predation by dogs and cats. Parasites Vectors 2023, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, L.M.E.; Ortiz, R.C.R.; Berumen, F.L.R.; Piña, F.J.G.; Delgado, R.M.R. Importancia del manejo de la población canina en situación de calle en México: Perspectivas y desafíos. CIBA Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Biol. Agropecu. 2023, 12, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Bryce, C.M. Dogs as Pets and Pests: Global Patterns of Canine Abundance, Activity, and Health. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orduña-Villaseñor, M.; Valenzuela-Galván, D.; Schondube, J.E. Tus mejores amigos pueden ser tus peores enemigos: Impacto de los gatos y perros domésticos en países megadiversos. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2023, 94, e944850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Corona, S.I.; Gomez-Vazquez, J.P.; López-Flores, E.A.; Vargas Estrada, D.; Arvizu-Tovar, L.O.; Pérez-Rivero, J.J.; Juárez Rodríguez, I.; Sierra Resendiz, A.; Soberanis-Ramos, O. Use of an Extrapolation Method To Estimate the Population of Cats and Dogs Living at Homes in Mexico in 2022; Veterinaria México OA: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2022; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Pelaez, M.; Echevarría, L.; Soler-Tovar, D.; Falcón, N. Métodos de contracepción en el control poblacional de perros: Un punto de vista de los médicos veterinarios de clínica de animales de compañía. Salud Tecnol. Vet. 2018, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca, C.A.; Polo, L.J.; Vargas, J. Sobrepoblación canina y felina: Tendencias y nuevas perspectivas. Rev. Fac. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2011, 58, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kustritz, R. Effects of surgical sterilization on canine and feline health and on society. Reprod. Domest. Anim. Zuchthyg. 2012, 47, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Martins, M.; Portugal, M.; Cardoso, L.; Martins-Bessa, A. The Impact of Pediatric Neutering in Dogs and Cats-A Retrospective Study. Animals 2023, 13, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B. Evaluating the benefits and risks of neutering dogs and cats. CABI Rev. 2010, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, C.V.; Scarlett, J.M.; Houpt, K.A. Long-term risks and benefits of early-age gonadectomy in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 224, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavides Melo, C.J.; Astaíza Martínez, J.M.; Rojas, M.L. Complicaciones por esterilización quirúrgica mediante ovariohisterectomía en perras: Revisión sistemática. Rev. Med. Vet. 2018, 1, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe Sarmiento, F.F.; Prada Delgado, Y.F.; Rodríguez Barajas, B.S.; Bayona Sánchez, J.A. Métodos de Esterilización en Caninos Y Felinos; Revisión de Literatura; Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia: Medellín, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo Santillán, N.S. Estimación de la Población de Perros Y Gatos Vagabundos Dentro Del Cantón Riobamba; Universidad de Cuenca: Cuenca, Ecuador, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zumpano, R.; Tortosa, A.; Degregorio, O.J. Estimación del impacto de la esterilización en el índice de crecimiento de la población de caninos. Rev. Investig. Vet. Del. Perú 2011, 22, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eade, J.A.; Roberston, I.D.; James, C.M. Contraceptive potential of porcine and feline zona pellucida A, B and C subunits in domestic cats. Reproduction 2009, 137, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Benka, V.A.; Briggs, J.R.; Driancourt, M.-A.; Maki, J.; Mora, D.S.; Morris, K.N.; Myers, K.A.; Rhodes, L.; Vansandt, L.M. Effectiveness of GonaCon as an immunocontraceptive in colony-housed cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018, 20, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, S.P.; Levy, J.K.; Hampton, A.L.; Collante, W.R.; Harris, A.L.; Brown, R.G. Evaluation of a porcine zona pellucida vaccine for the immunocontraception of domestic kittens (Felis catus). Theriogenology 2002, 58, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovo, M.; Petrov, M.; Klissourska, D.; Mollova, M. Contraceptive potential of porcine zona pellucida in cats. Theriogenology 1995, 43, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.K.; Friary, J.A.; Miller, L.A.; Tucker, S.J.; Fagerstone, K.A. Long-term fertility control in female cats with GonaCon™, a GnRH immunocontraceptive. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.K.; Mansour, M.; Crawford, P.C.; Pohajdak, B.; Brown, R.G. Survey of zona pellucida antigens for immunocontraception of cats. Theriogenology 2005, 63, 1334–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, S.; Jelinski, M.; Stotish, R. Assessment of the immunological and biological efficacy of two different doses of a recombinant GnRH vaccine in domestic male and female cats (Felis catus). J. Reprod. Immunol. 2004, 64, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, C.; Volpato, R.; Destro, F.; Trevisol, E.; Sousa, N.R.; Guaitolini, C.; Derussi, A.; Rascado, T.; Lopes, M.D. Ovarian activity reversibility after the use of deslorelin acetate as a short-term contraceptive in domestic queens. Theriogenology 2012, 78, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furthner, E.; Roos, J.; Niewiadomska, Z.; Maenhoudt, C.; Fontbonne, A. Contraceptive implants used by cat breeders in France: A study of 140 purebred cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2020, 22, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, F.; Stornelli, M.C.; Tittarelli, C.M.; Savignone, C.A.; Dorna, I.; de la Sota, R.; Stornelli, M.A. Suppression of estrus in cats with melatonin implants. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Merlo, M.; Faya, M.; Blanco, P.G.; Carranza, A.; Barbeito, C.; Gobello, C. Failure of a single dose of medroxyprogesterone acetate to induce uterine infertility in postnatally treated domestic cats. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goericke-Pesch, S.; Georgiev, P.; Atanasov, A.; Albouy, M.; Navarro, C.; Wehrend, A. Treatment of queens in estrus and after estrus with a GnRH-agonist implant containing 4.7 mg deslorelin; hormonal response, duration of efficacy, and reversibility. Theriogenology 2013, 79, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.; Swanson, W.; Wildt, D.; Brown, J. Influence of oral melatonin on natural and gonadotropin-induced ovarian function in the domestic cat. Theriogenology 2004, 61, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubion, S.; Driancourt, M. Controlled delivery of a GnRH agonist by a silastic implant (Gonazon) results in long-term contraception in queens. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009, 44, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toydemir, T.; Kılıçarslan, M.; Olgaç, V. Effects of the GnRH analogue deslorelin implants on reproduction in female domestic cats. Theriogenology 2012, 77, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.C.; Bergman, D.L.; Wenning, K.M.; Miller, L.A.; Slate, D.; Jackson, F.R.; Rupprecht, C.E. No adverse effects of simultaneous vaccination with the immunocontraceptive GonaCon™ and a commercial rabies vaccine on rabies virus neutralizing antibody production in dogs. Vaccine 2009, 27, 7210–7213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmailnejad, A.; Nikahval, B.; Mogheiseh, A.; Karampour, R.; Karami, S. The detection of canine anti-sperm antibody following parenteral immunization of bitches against homogenized whole sperm. Basic Clin. Androl. 2020, 30, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Toor, S.; Minhas, V.; Chaudhary, P.; Raman, M.; Anoop, S.; Panda, A.K. Contraceptive efficacy of recombinant porcine zona proteins and fusion protein encompassing canine ZP3 fragment and GnRH in female beagle dogs. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2022, 87, e13536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Fang, F. Immunization of dogs with recombinant GnRH-1 suppresses the development of reproductive function. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahi-Brown, C.A.; Yanagimachi, R.; Hoffman, J.; Huang, T., Jr. Fertility control in the bitch by active immunization with porcine zonae pellucidae: Use of different adjuvants and patterns of estradiol and progesterone levels in estrous cycles. Biol. Reprod. 1985, 32, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahi-Brown, C.A.; Huang, T.T., Jr.; Yanagimachi, R. Infertility in bitches induced by active immunization with porcine zonae pellucidae. J. Exp. Zool. 1982, 222, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, B.; Clavio, A.; Singh, M.; Rathnam, P.; Bukharovich, Y.; Reimers, T., Jr.; Saxena, A.; Perkins, S. Modulation of ovarian function in female dogs immunized with bovine luteinizing hormone receptor. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2002, 37, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Pino, F.; Gutiérrez-Cedillo, V.; Canales-Vargas, E.J.; Gress-Ortega, L.R.; Miller, L.A.; Rupprecht, C.E.; Bender, S.C.; García-Reyna, P.; Ocampo-López, J.; Slate, D. Concomitant administration of GonaCon™ and rabies vaccine in female dogs (Canis familiaris) in Mexico. Vaccine 2013, 31, 4442–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijerink, N.; Bhatti, S.; Okkens, A.; Dieleman, S.; Duchateau, L.; Kooistra, H. Pulsatile plasma profiles of FSH and LH before and during medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment in the bitch. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brändli, S.; Palm, J.; Kowalewski, M.P.; Reichler, I.M. Long-term effect of repeated deslorelin acetate treatment in bitches for reproduction control. Theriogenology 2021, 173, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Corrada, Y.; Hermo, G.; Johnson, C.; Trigg, T.; Gobello, C. Short-term progestin treatments prevent estrous induction by a GnRH agonist implant in anestrous bitches. Theriogenology 2006, 65, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gontier, A.; Youala, M.; Fontaine, C.; Raibon, E.; Fournel, S.; Briantais, P.; Rigaut, D. Efficacy and safety of 4.7 mg deslorelin acetate implants in suppressing oestrus cycle in prepubertal female dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczak, A.; Janowski, T.; Zdunczyk, S.; Failing, K.; Schuler, G.; Hoffmann, B. Attempts to downregulate ovarian function in the bitch by applying a GnRH agonist implant in combination with a 3ß-hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase blocker; a pilot study. Theriogenology 2020, 145, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D.; Gram, A.; Kowalewski, M.P.; Schäfer-Somi, S.; Kuru, M.; Boos, A.; Aslan, S. Expression of GnRH receptor in the canine corpus luteum, and luteal function following deslorelin acetate-induced puberty delay. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017, 52, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D.; Schäfer-Somi, S.; Kurt, B.; Kuru, M.; Kaya, S.; Kaçar, C.; Aksoy, Ö.; Aslan, S. Clinical use of deslorelin implants for the long-term contraception in prepubertal bitches: Effects on epiphyseal closure, body development, and time to puberty. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LACOSTE, D.; DUBÉ, D.; TRUDEL, C.; BÉLANGER, A.; LABRIE, F. Normal gonadal functions and fertility after 23 months of treatment of prepubertal male and female dogs with the GnRh agonist [D-Trp6, des-Gly-NH210] GnRH ethylamide. J. Androl. 1989, 10, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, G.; Rizzo, S.; Quartuccio, M.; Macri, F.; Pagano, G.; Taormina, A.; Cristarella, S.; Zanghi, A. Deslorelin Implants in Pre-pubertal Female Dogs: Short-and Long-Term Effects on the Genital Tract. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2014, 49, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Corona, S.; León, P.; Mendieta, E.; Villanueva, M.; Salame, A.; Vargas, D.; Mora, G.; Serrano, H.; Villa-Godoy, A. Effect of a single application of coumestrol and/or dimethyl sulfoxide, on sex hormone levels and vaginal cytology of anestrus bitches. Vet. México 2019, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Corona, S.; León-Ortiz, P.; Villanueva-Martínez, M.; Mendoza-Rodríguez, C.; Martínez-Maya, J.; Serrano, H.; Vargas, D.; Villa-Godoy, A. Administration of Coumestrol and/or Dimethyl Sulfoxide Affects Vaginal Epithelium and Sex Hormones in Female Dog. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2022, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, S.; Stelletta, C.; Milani, C.; Gelli, D.; Falomo, M.E.; Mollo, A. Clinical use of deslorelin for the control of reproduction in the bitch. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009, 44, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubion, S.; Desmoulins, P.; Rivière-Godet, E.; Kinziger, M.; Salavert, F.; Rutten, F.; Flochlay-Sigognault, A.; Driancourt, M. Treatment with a subcutaneous GnRH agonist containing controlled release device reversibly prevents puberty in bitches. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 1651–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahara, K.; Tsutsui, S.; Naito, Y.; Fujikura, K. Prevention of estrus in bitches by subcutaneous implantation of chlormadinone acetate. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1993, 55, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, T.; Tamada, H.; Inaba, T.; Mori, J. Prevention of estrus in the bitch with chlormadinone acetate administered orally. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1992, 54, 595–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schäfer-Somi, S.; Kaya, D.; Sözmen, M.; Kaya, S.; Aslan, S. Pre-pubertal treatment with a Gn RH agonist in bitches—Effect on the uterus and hormone receptor expression. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2018, 53, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M.; Armour, A.; Wright, P. The influence of exogenous progestin on the occurrence of proestrous or estrous signs, plasma concentrations of luteinizing hormone and estradiol in deslorelin (GnRH agonist) treated anestrous bitches. Theriogenology 2006, 66, 1513–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, C.; Diaz, J.; Rosa, D.; Mattioli, G.; Romero, G.G.; Gobello, C. Effect of a GnRH antagonist on GnRH agonist–implanted anestrous bitches. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiente, C.; Romero, G.G.; Corrada, Y.; De la Sota, P.; Hermo, G.; Gobello, C. Interruption of the canine estrous cycle with a low and a high dose of the GnRH antagonist, acyline. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concannon, P.; Weinstein, P.; Whaley, S.; Frank, D. Suppression of luteal function in dogs by luteinizing hormone antiserum and by bromocriptine. Reproduction 1987, 81, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gier, J.; Wolthers, C.; Galac, S.; Okkens, A.; Kooistra, H. Effects of the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor trilostane on luteal progesterone production in the dog. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, T.; Fingerhut, J.; Kowalewski, M.P.; Zduńczyk, S.; Domosławska, A.; Jurczak, A.; Boos, A.; Schuler, G.; Hoffmann, B. In vivo investigations on luteotropic activity of prostaglandins during early diestrus in nonpregnant bitches. Theriogenology 2014, 82, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, M.; Ihle, S.; Siemieniuch, M.; Gram, A.; Boos, A.; Zduńczyk, S.; Fingerhut, J.; Hoffmann, B.; Schuler, G.; Jurczak, A. Formation of the early canine CL and the role of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in regulation of its function: An in vivo approach. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onclin, K.; Verstegen, J. In vivo investigation of luteal function in dogs: Effects of cabergoline, a dopamine agonist, and prolactin on progesterone secretion during mid-pregnancy and-diestrus. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 1997, 14, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.T.; Gram, A.; Nowaczyk, R.; Boos, A.; Hoffmann, B.; Janowski, T.; Kowalewski, M.P. Prostaglandin-mediated effects in early canine corpus luteum: In vivo effects on vascular and immune factors. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 19, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers-Wolthers, C.; De Gier, J.; Rutten, V.; van Kooten, P.; Leegwater, P.; Schaefers-Okkens, A.; Kooistra, H. The effects of kisspeptin agonist canine KP-10 and kisspeptin antagonist p271 on plasma LH concentrations during different stages of the estrous cycle and anestrus in the bitch. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers-Wolthers, C.; De Gier, J.; Walen, M.; Van Kooten, P.; Lambalk, C.; Leegwater, P.; Roelen, B.; Schaefers-Okkens, A.; Rutten, V.; Millar, R. In vitro and in vivo effects of kisspeptin antagonists p234, p271, p354, and p356 on GPR54 activation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers-Wolthers, K.H.; De Gier, J.; Kooistra, H.S.; Rutten, V.P.; Van Kooten, P.J.; De Graaf, J.J.; Leegwater, P.A.; Millar, R.P.; Schaefers-Okkens, A.C. Identification of a novel kisspeptin with high gonadotrophin stimulatory activity in the dog. Neuroendocrinology 2014, 99, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terse, P.S.; Peggins, J.; Seminara, S.B. Safety Evaluation of KP-10 (Metastin 45–54) Following once Daily Intravenous Administration for 14 Days in Dog. Int. J. Toxicol. 2021, 40, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogheiseh, A.; Khafi, M.S.A.; Ahmadi, N.; Farkhani, S.R.; Bandariyan, E. Ultrasonographic and histopathologic changes following injection of neutral zinc gluconate in dog’s ovaries. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 26, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, A.; Mogheiseh, A.; Nazifi, S.; Ahrari-Khafi, M.; Dehghanian, A.; Vesal, N.; Bigham-Sadegh, A. Effect of direct therapeutic ultrasound exposure of ovaries on histopathology, inflammatory response, and oxidative stress in dogs. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaut, R.; Jackman, J.; Brewer, M.; Mendoza, K.; Jones, D.; Narasimhan, B. A polyanhydride-based implant. Single dose vaccine Platf. long-term immunity. Vaccine 2018, 36, 1024–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaut, R.G.; Brewer, M.T.; Hostetter, J.M.; Mendoza, K.; Vela-Ramirez, J.E.; Kelly, S.M.; Jackman, J.K.; Dell’Anna, G.; Howard, J.M.; Narasimhan, B. A single dose polyanhydride-based vaccine platform promotes and maintains anti-GnRH antibody titers. Vaccine 2018, 36, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samoylov, A.; Napier, I.; Morrison, N.; Cochran, A.; Schemera, B.; Wright, J.; Cattley, R.; Samoylova, T. DNA Vaccine Targeting Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor and Its Application in Animal Contraception. Mol. Biotechnol. 2019, 61, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandam, N.P.; Prakash, D.; Thimmareddy, P. Immunocontraceptive potential of a GnRH receptor-based fusion recombinant protein. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasetska, A. Non-surgical methods of regulation reproductive function and contraception males of domestic animals. Ukr. J. Vet. Agric. Sci. 2020, 3, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoylova, T.I.; Braden, T.D.; Spencer, J.A.; Bartol, F.F. Immunocontraception: Filamentous Bacteriophage as a Platform for Vaccine Development. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 3907–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.K.; Jones, R.L.; Kraneburg, C.J.; Cochran, A.M.; Samoylov, A.M.; Wright, J.C.; Hutchinson, C.; Picut, C.; Cattley, R.C.; Martin, D.R.; et al. Phage constructs targeting gonadotropin-releasing hormone for fertility control: Evaluation in cats. J. Feline. Med. Surg. 2020, 22, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risso, A.; Corrada, Y.; Barbeito, C.; Díaz, J.D.; Gobello, C. Long-term-release GnRH agonists postpone puberty in domestic cats. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 936–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigg, T.; Wright, P.; Armour, A.; Williamson, P.; Junaidi, A.; Martin, G.; Doyle, A.; Walsh, J. Use of a GnRH analogue implant to produce reversible long-term suppression of reproductive function in male and female domestic dogs. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 2001, 57, 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Gobello, C. New GnRH analogs in canine reproduction. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2007, 100, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamada, H.; Kawate, N.; Inaba, T.; Sawada, T. Long-term prevention of estrus in the bitch and queen using chlormadinone acetate. Can. Vet. J. 2003, 44, 416. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, B.; Wilkins, A.; Whiting, S.; Liang, M.; Rebourcet, D.; Nixon, B.; Aitken, R.J. Development of peptides for targeting cell ablation agents concurrently to the Sertoli and Leydig cell populations of the testes: An approach to non-surgical sterilization. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0292198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faya, M.; Marchetti, C.; Priotto, M.; Grisolía, M.; D’Francisco, F.; Gobello, C. Postponement of canine puberty by neonatal administration of a long term release GnRH superagonist. Theriogenology 2018, 118, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Roux, N.; Genin, E.; Carel, J.-C.; Matsuda, F.; Chaussain, J.-L.; Milgrom, E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10972–10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminara, S.B.; Messager, S.; Chatzidaki, E.E.; Thresher, R.R.; Acierno, J.S., Jr.; Shagoury, J.K.; Bo-Abbas, Y.; Kuohung, W.; Schwinof, K.M.; Hendrick, A.G. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Hernández, J.M.; Martin, G.B.; Becerril-Pérez, C.M.; Pro-Martínez, A.; Cortez-Romero, C.; Gallegos-Sánchez, J. Kisspeptin stimulates the pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) during postpartum anestrus in ewes undergoing continuous and restricted suckling. Animals 2021, 11, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colledge, W. Transgenic mouse models to study Gpr54/kisspeptin physiology. Peptides 2009, 30, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, M.; Detheux, M.; Vandenbogaerde, A.; Communi, D.; Vanderwinden, J.-M.; Le Poul, E.; Brézillon, S.; Tyldesley, R.; Suarez-Huerta, N.; Vandeput, F. The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 34631–34636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, I.J. Control of GnRH secretion: One step back. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2011, 32, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, R.; Garcia-Galiano, D.; Roseweir, A.; Romero, M.; Sanchez-Garrido, M.; Ruiz-Pino, F.; Morgan, K.; Pinilla, L.; Millar, R.; Tena-Sempere, M. Critical roles of kisspeptins in female puberty and preovulatory gonadotropin surges as revealed by a novel antagonist. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan-Mei, Z.; Yi, D.; Teketay, W.; Hai-Jing, J.; Sohail, A.; Gui-Qiong, L.; Xun-Ping, J. Recent advances in immunocastration in sheep and goat and its animal welfare benefits: A review. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, M.; Sosulski, A.E.; Zhang, L.; Saatcioglu, H.D.; Wang, D.; Nagykery, N.; Sabatini, M.E.; Gao, G.; Donahoe, P.K.; Pépin, D. AMH/MIS as a contraceptive that protects the ovarian reserve during chemotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E1688–E1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolghanabadi, M.; Sedigh, H.S.; Mirshokraei, P.; Rajabioun, M. Simultaneously administration of cabergoline and PMSG reduces the duration of estrus induction in anestrous bitches. Vet. Res. Forum 2023, 14, 665–671. [Google Scholar]

- Dissen, G.A.; Lomniczi, A.; Boudreau, R.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Davidson, B.L.; Ojeda, S.R. Targeted gene silencing to induce permanent sterility. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naso, M.F.; Tomkowicz, B.; Perry III, W.L.; Strohl, W.R. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for gene therapy. BioDrugs 2017, 31, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilez Lopez, E.J.; Cuadra Palacios, J.D. Comparación de Dos Técnicas Quirúrgicas, para Ovariohisterectomía Felina en Clínica Veterinaria Mimos. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Agraria, La Molina, Peru, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, B.A.L.; Argüello, V.F.; Rodríguez, J.G.; Hernandez, A.A. Técnica de ovariectomía con mínima invasión en caninos en México. Jóvenes Cienc. 2022, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ealo, I.M.; Berna, I.L.; Eugenia, M. Esterilización en Hembras de la Especie Canina: Ovariectomía vs. Ovariohisterectomía. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Zaragoza Facultad de Veterinaria, Zaragoza, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Masache, J.L.; Brito, M.C.; Sagbay, C.F.; Webster, P.G.; Garnica, F.P.; Mínguez, C. Ovariectomía en perras: Comparación entre el abordaje medial o lateral. Rev. Investig. Vet. Del. Perú 2016, 27, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.E. Female reproduction. Cat 2011, 1195–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Wigham, E.E.; Moxon, R.S.; England, G.C.; Wood, J.L.; Morters, M.K. Seasonality in oestrus and litter size in an assistance dog breeding colony in the United Kingdom. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Contraceptive Method (Number of Articles) | References |

|---|---|

| Female Cats | |

| Vaccines (8) | Eade et al., 2009 [19]; Fischer et al., 2018 [20]; Gorman et al., 2002 [21]; Ivanovo et al., 1995 [22]; Levy et al., 2011 [23]; Levy et al., 2005 [24]; Robbins et al., 2004 [25]; Saxena et al., 2003 [2]. |

| Hormone analogs (8) | Ackermann et al., 2012 [26]; Furthner et al., 2020 [27]; Gimenez et al., 2009 [28]; Goericke-Lopez Merlo et al., 2016 [29], Pesch et al., 2013 [30]; Graham et al., 2004 [31]; Rubion and Driancourt, 2009 [32]; Toydemir et al., 2012 [33]. |

| Other contraception methods (1) | Vansandt et al., 2023 [1] |

| Female Dogs | |

| Vaccines (8) | Bender et al., 2009 [34]; Esmailnejad et al., 2020 [35]; Gupta et al., 2022 [36]; Liu et al., 2015 [37]; Mahi-Brown et al., 1985 [38]; Mahi-Brown et al., 1982 [39]; Saxena et al., 2002 [40]; Vargas-Pino et al., 2013 [41]. |

| Hormone analogs (19) | Beijerink et al., 2008 [42]; Brändli et al., 2021 [43]; Corrada et al., 2006 [44]; Gontier et al., 2022 [45]; Jurczak et al., 2020 [46]; Kaya et al., 2017 [47]; Kaya et al., 2015 [48]; Lacoste et al., 1989 [49]; Marino et al., 2014 [50]; Peña-Corona et al., 2019 [51]; Peña-Corona et al., 2022 [52]; Romagnoli et al., 2009 [53]; Rubion et al., 2006 [54]; Sahara et al., 1993 [55]; Sawada et al., 1992 [56]; Schäfer-Somi et al., 2018 [57]; Sung et al., 2006 [58]; Valiente et al., 2009 [59]; Valiente et al., 2009 [60]. |

| Compounds that regulate the CL function (6) | Concannon et al., 1987 [61]; De Gier et al., 2011 [62]; Janowski et al., 2014 [63]; Kowalewski et al., 2015 [64]; Onclin and Verstegen, 1997 [65]; Pereira et al., 2019 [66]. |

| Kisspeptin (4) | Albers-Wolthers et al., 2016 [67]; Albers-Wolthers et al., 2017 [68]; Albers-Wolthers et al., 2014 [69]; Terse et al., 2021 [70]. |

| Other contraception methods (2) | Mogheiseh et al., 2017 [71]; Rajabi et al., 2023 [72] |

| Age, Breed (n = Number of Animals) | Previous Treatment | Compound | Doses Administration | Administration Protocol | Main Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccines Tested in Female Cats | ||||||

| 8-month-old anestrous domestic cats (n = 9) | Quarantined for 5 to 8 days, a light:dark schedule of 8:16 h; any male cats nearby | Bovine (LH-R) | 0.5 mg of LH-R per implant; boost via i.m. with 0.1 mg LH-R; control: NaCl 0.9% solution | The implants were inserted on day 0; boost: on days 98, 139, 160, and 193; on day 345, LH was administered to confirm infertility | The estrus cycle of cats had normal behavior; still, inhibition of LH-R was 50 to 70% due to anti-LH-R antibodies, which was associated with suppression of serum P4, possibly indicating poor CL function | [2] |

| Adult in estrus shorthair cats (n = 20) | Housed at 21–23 °C for 30 days in a light:dark cycle of 12:12 h | GonaConTM | 200 μg of GnRH in an inactivated Mycobacterium avium; control: all components except GnRH-KLH | A single i.m. dose; 120 days later, a male cat was introduced | All control cats got pregnant; vaccinated cats were infertile for 1–5 years with antibody titers > 16,000; long-term infertile cats had an antibodies titer of 256,000 | [23] |

| Domestic, short-, or long-hair cats (n = 30) | Housed at 20–27 °C and natural photoperiod | GonaConTM | 0.5 mL of GonaConTM; control: 0.5 mL of sterile saline solution | A single dose; four months later, fertile male cats were introduced | 70% of vaccinated cats got pregnant within the first year of the treatment; the estrus cycle was not altered | [20] |

| 15- to 20-week-old cats (n = 15, 3 per group) | Housed at 21 to 23 °C with a light:dark cycle of 14:10 h | SpayVacTM vaccine based on pZP antigens | 50 μg of SIZP from cow or 100 μg of SIZP from cat, ferret, dog, and mink, encapsulated in liposomes, emulsified in Freund’s complete adjuvant | A single dose; 20 weeks later; cats immunized with feline ZP were boosted after 32 weeks and 5 weeks later were bred again | All cats produced antibodies; immunogenicity: mink > ferret > dog > cat; all cats got pregnant after breeding | [24] |

| 8- to 12-week-old cats, specific pathogen-free kittens (n = 30) | Housed at a temperature around 21–23 °C with a light:dark cycle of 14:10 h | SpayVacTM | 200 μg of SIPZ in liposomes and complete Freund’s adjuvant or alum; control: all components except SIPZ | I.m. dose under anesthesia, with a breeding trial 3 months later | Antibodies of IgG anti-porcine ZP were produced within 4 weeks; neither formulation prevented estrus cycling at maturity or reduced fertility | [21] |

| Domestic 2–3-year-old cats (n = 5–8 per group) | Housed next to a male, separated by wire mesh partitions, at 23 °C, light:dark cycle of 12:12 h | ZP polypeptide (55 kDa) and feline ZP A, B, and C subunits expressed by plasmid vectors | 75 μg of pZP emulsified in Freund’s incomplete adjuvant for first immunization and complete for boosts; DNA vaccine expressing autologous feline ZP A, B, and C subunits; control: protoprep gel without ZP | Three boosts s.c. at weeks 0, 4, and 8; DNA feline ZP i.m. A, B, and C subunits and control group; three boosts at 1-month intervals | All cats produced IgG antibodies without feline ZP reactivity at week 10 and got pregnant; cats vaccinated with feline ZP A, B, and C developed low antibody titers until weeks 4 and 11; no significant difference in contraception for either number of follicles between the control and DNA-vaccinated groups | [19] |

| Domestic cats (n = 3 in group 1 and 5 in group 2) | Housed in groups of 2 or 3 under natural light conditions for 10 to 14 days before immunization | Solubilized porcine ZP | 300 or 400 μg of pZP (in complete Freund’s adjuvant for the first dose and incomplete Freund’s adjuvant for boosts) in PBS and 2.0 mg of FSH and hCG; control: adjuvant and PBS | (1) Half of 300 μg injected s.c. divided in 4 injections at a 10-day interval; the missing quantity was administered on day 150; (2) half of 400 μg was administered i.m., divided in 4 injections at a 2-week interval; the missing quantity was injected 92 days after the first injection | Anti-ZP antibodies inhibit sperm binding to oocytes in vitro; a cat with the lowest antibody titer became pregnant even though it inhibited sperm binding in vitro | [22] |

| Domestic cats of 8–9 weeks (n = 15) | Acclimated 2 weeks prior to the study in an environmentally enriched room, at 22 ± 2 °C, with a light:dark cycle of 12:12 h | IPS-21, a recombinant fusion protein of eight tandem repeats of GnRH | 10 or 100 μg of IPS-21, combined with phosphate-buffered saline, adjuvant EMULSIGEN, and dimethyl dioctadecyl ammonium bromide as an immunostimulant; control: without IPS-21 antigen | Immunizations s.c. on days 0, 48, and 243 | All immunized cats developed anti-GnRH antibodies 7 days after the second immunization; the third immunization stimulated an increase in antibody titers; any female immunized showed neither signs of estrous nor became pregnant; they were anestrous due to the low P4 serum levels | [25] |

| Vaccines Tested in Female Dogs | ||||||

| Mixed-breed and -aged bitches, in late metaestrus or anestrus (n = 14) | Some had previous parity | Crude (cCP) or pure (pCP) porcine ZP | 0.4 mg of cZP or pure pZP in 0.5 mL of 0.9% NaCl solution or Tris Buffer and different adjuvants as Freund’s, Al(OH)3, or CP-20 | s.c. (with Al (OH)3 as adjuvant) or i.m. (immunized with CP-20), around four times in a monthly interval | Immunized bitches turned out infertile regardless of the adjuvant | [38] |

| Mongrel bitches of 1–3 years, mid-metestrus to anestrus until proestrus (n = 7) | Housed in pairs indoor–outdoor; four had previously whelped | Porcine or canine ZP | 2000 isolated and solubilized either porcine or canine ZP in 0.5 mL of PBS and 0.5 mL of Freund’s complete adjuvant; the boost contained 1000 ZP and Freund’s incomplete adjuvant instead | First immunization i.m. with subsequent monthly s.c. boosters until the elevation of titer antibodies had no more elevation; control bitches were treated identically, omitting ZP | ZP-treated groups developed antibodies; the pZP group had higher titles of antibodies and abnormal estrus cycles | [39] |

| Male and female, Chinese, rural, 16-month-old dogs (n = 6, 3 per group) | Housed individually in cages 4 weeks prior | Recombinant GnRH-I protein | 1 mL of an emulsion of 1.5 mg of GnRH-I with a maltose-binding protein (MBP) emulsified in 3 mL of PBS and 3 mL of Al(OH)3 adjuvant; control: MBP and adjuvant | I.m at 16 months old and after 6 weeks | Immunized dogs developed antibodies; serum P4 levels decreased | [37] |

| Female dogs of mixed breeds over 5 months of age (n = 18, 6 per group) | From dog round-ups; dogs were separated into kennels and under oversight by a veterinarian | GonaConTM | 0.5 mL GonaConTM which contains 500 μg of GnRH conjugated to KLH and 85 μg of Mycobacterium avium; control: 1 mL of rabies commercial vaccine DEFENSOR-3 with inactivated virus | Group 1: GonaConTM injected i.m.; group 2: DEFENSOR-3 i.m.; group 3: GonaConTM and DEFENSOR-3 vaccines injected i.m | Antibody levels increased in three groups; results in group 3 show that rabies and immunocontraception vaccines could be administered together | [34] |

| Female beagle in proestrus, 1–3-year-old dogs (n = 12, 4 per group) | - | Porcine ZP3, ZP4 | 1 mL of a physical mixture 1:1 (500 μg of each protein): porcine ZP 3 with promiscuous T cell epitope of tetanus toxoid (TT-KK-pZP3); porcine ZP 4 with promiscuous T cell epitope of RNAase (bRNase-KK-pZP4); recombinant fusion protein encompassing dog ZP3 fragment and two copies of GnRH with appropriate promiscuous T cell epitopes (dZP3-GnRH2); control: only adjuvant | I.m. thrice every 4 weeks for each protein; a fourth boost on day 383 | The groups immunized with recombinant proteins produced high antibodies titer against GnRH and ZP, especially those immunized with dZP3-GnRH2; the antibodies produced reacted specifically with dog ZP; the group immunized with dZP3-GnRH2 had the lowest number of pregnancy outcomes | [36] |

| Mature, mixed-breed bitches in anestrus (n = 15, 5 per group) | Antiparasitic treatment with praziquantel and mebendazole 2 weeks prior | Sperm | 1 mL of high dose of sperm vaccine (200 × 106 cells/mL); 1 mL of low dose of sperm vaccine (100 × 106 cells/mL); boost doses just switched adjuvant for Freund’s incomplete |

First immunization s.c. in four sites across the shoulder area; boosters were adminstered at weeks 1, 2, 4, and 6 |

Bitches immunized developed specific anti-sperm antibodies; those injected with a high dose achieved a higher titer (after the third immunization) than those injected with a low dose; there was not any dominant follicle nor active in CL | [35] |

| 9-month-old female dogs (beagles, in the fifth day of vaginal bleeding (probably proestrus)), OM 8 to 12 kg (n = 10, 7 in the trial group and 3 in the control group) | Maintained for 5 to 8 days, alone or with compatible running partners on 12:12 h light:dark cycles | LH-R | First immunization: 0.5 mg/per implant of 100 μL of LH-R encapsulated in a silastic subdermal implant emulsified with ‘Gerbu’ as the adjuvant (1.44 mg/per implant); control: saline solution emulsified in the adjuvant; boost injection: 0.1 mg of LH-R in the adjuvant | The first immunization (week 0) was administered in a subdermal implant; oat week 14, the booster was administered by i.m. and 3 more boosters were administered at weeks 19, 22, and 27 post-implantation |

Antibodies were detected in serum 3 weeks after the first immunization; serum P4 levels decreased because of a lack of ovulation and CL function; dogs remained in the diestrus and anestrus phase; serum estradiol levels remained in both the immunized and the control dogs; there were not any signs of “standing heat” nor vaginal bleeding and failed ovulation when induced by LH-RH | [40] |

| Twenty female dogs of mixed breeds, medium or large | Held for a 60-day observation and adaptation period | GonaCon™ | Each 0.5 mL dose contained 500 μg of the GnRH conjugate and 21 μg of inactivated Mycobacterium avium in the adjuvant | GonaCon™ vaccines were administered once i.m. in the upper-left hind leg | Significant increases in anti-GnRH antibodies; P4 was suppressed in comparison to controls | [41] |

| Age, Breed (n = Number of Animals) | Previous Treatment | Compound | Doses Administration | Administration Protocol | Main Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone Analogs Tested in Female Cats | ||||||

| Queens in estrus between 2 to 5 years (n = 20, 10 per group) | Acclimated 2 months prior with natural daylight | GnRH analog | Suprelorin 4.7 mg implant (Virbac®) | Administration by s.c. injection; group A: treated 3.2 ± 0.8 days after the beginning of estrus; group B: treated 7 days after the end of estrus | Group A: the estrus stopped at 4.1 ± 2.5 days after treatment; estrus induction was observed 6, 138, and 155 days after treatment; group B: increase of E2 and P4 levels greater than group A one day after treatment; eight cats from this group got pregnant after mating trials | [30] |

| Purebred cats in proestrus; Melovine in interestrus (n = 140/83 females) | - | GnRH analog | Suprelorin 4.7 mg implant (Virbac®), 18 mg of melatonin implant (Melovine®) | 41 and 42 queens were implanted s.c. with deslorelin and melatonin, respectively | 26/41 female cats implanted had estrus inhibited for 8–38 months; 12/26 queens produced a litter; 33/42 queens implanted with melatonin had estrus inhibited for 21–277 days after implantation; 12/33 queens had a subsequent litter | [27] |

| Mature (2–3 years old) mixed-breed domestic queens in interestrus or diestrus (n = 10) | Kept in an experimental cattery, with light exposure of 12 h/day | GnRH analog | Implant containing 4.7 mg of deslorelin acetate | Implanted s.c. on day 0; on day 90, they were removed; on day 100, estrus and ovulation were induced with eCG (i.m.), followed by hCG (i.m.) 84 h later | After deslorelin application, 40% of queens ovulated; 4 queens had signs of estrus, but just 1 ovulated; 3 queens showed ovulation did not have signs consistent with estrus; mean plasma P4 levels decreased gradually after placement, and rapidly increased after removal | [26] |

| Female, short-haired, mixed-breed, 1–5-year-old, domestic cats (n = 28) | The queens had previously experienced 6–10 estrus cycles; 12 of them had litters beforehand and the fertility of the rest was unknown; kept at 15–17 °C and 12:12 h of light:dark cycles | GnRH analog and MA | Group 1 (G1): 9.5 mg deslorelin implant; group 2 (G2): 9.5 mg of deslorelin implant and 5 mg of MA tablets; control group: placebo implants | Implants in G1 were administered s.c.; in G2, implants were administered together with MA 14 days and 12 h before and 14 days after implants; they remained for 18.5 months and were ovariectomized | Fecal E2 levels were significantly lower in treatment groups (especially the G2 after one day) than the control group; most of the queens treated did not have estrus behavior for 18.5 months; queens that showed estrus behaviors after implantation did not become pregnant; the ovaries from G1 and G2 had no presence of CL nor fewer follicles and uterine thickness was lower | [33] |

| 1- to 4-year-old queens and tomcats (n = 12, 6 per group) | 14:10 h of light:dark cycles | GnRH agonist | Implant containing 20 mg of Gonazon | s.c. on the neck, and it remained for 3 years | Gonazon inhibited ovulation in all treated queens; Gonazon concentrations peaked after a week of the implant insertion, remained for a month, and decreased slowly | [32] |

| Domestic short-hair 8- to 18-month-old queens (n = 12) | Hosted in pairs under artificial fluorescent lighting (12:12 h light:dark cycle at 7:00 p.m.) | Melatonin | 30 mg of melatonin; ovarian stimulation (OS): 100 IU eCG i.m. to stimulate follicular development, followed by 75 IU hCG i.m. 80 h later to induce final oocyte maturation and ovulation | Experiment 1 (n = 4): oral capsule administration; experiment 2 (n = 6): oral administration for 35 days, 3 h before lights off; experiment 3 (n = 5 per group): OS by eCG/hCG only, or 2 days after pre-treatment with oral melatonin with eCG administration; experiment 4 (n = 6 per group): examination after AI, in queens with OS | 3/6 melatonin-treated cats had elevated fecal E2 levels during treatment; their estrus cycle returned after cessation; treatment with melatonin and eCG reduced ancillary follicle development and had no significant effect on the quantity or quality of AI-produced embryos; fecal E2 levels were lower in queens pre-treated with melatonin than the only-eCG-treated with no significant difference; melatonin inhibited ovarian activity without adverse impact on embryo quality after artificial insemination | [31] |

| Mature (12–14 months) female cats in interestrus and estrus (n = 9 in the trial group; 5 in the placebo group) | Kept in cages for 45 days under artificial illumination in 14:10 h of light:dark cycles | Melatonin | 18 mg melatonin implant, placebo without melatonin | Placed s.c. in the subsequent estrus, all received a second implant; a male was introduced in the following estrus after the second dose | Melatonin implants suppress estrus for 2–4 months; within 9 to 11 d after melatonin implant insertion during estrus, 78% of queens had estrous behavior; 75% of melatonin-implanted cats became pregnant | [28] |

| Postnatal female kittens (n = 10) | Indoor catteries with 14 h of light per day and weaned at the age of 40 days | Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 10 mg/animal of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) (n = 6); placebo: 0.2 mL of corn oil (n = 4) | Within the first 24 h of birth, kittens were randomly assigned to treatment, which was administered subcutaneously | Ovulation occurred in 4/6 MPA-treated kittens and 3/4 from placebo group after estrus and became pregnant; all pubertal kittens showed normal sexual behavior and when exposed to males during estrus accepted repeated matings | [29] |

| Hormone Analogs Tested inFemale Dogs | ||||||

| Cross-breed, medium-sized, prepubertal bitches (4–5 months old) (n = 13, 5 in group 1, 4 in group 2 and placebo group) | Housed in indoor–outdoor runs, 12 h daylight exposure | GnRH analog | Implants with Suprelorin (deslorelin acetate): group 1: 9.4 mg, group 2: 4.7 mg, group 3: placebo (sodium chloride 0.9%) | s.c. insertions in the interscapular region | Half of the bitches developed estrus after 83 and 102 weeks Serum levels of estradiol 17β increased at weeks 37 to 49 in 3 bitches in each group; there was not any significant change 40 weeks of treatment | [48] |

| Healthy, caucasian shepherd and kangal cross-breed, prepubertal bitches aged 4 months and 9 kg in body weight (n = 13) | - | GnRH analog | 9.4 mg of deslorelin acetate implant (n = 5), 4.7 mg of deslorelin acetate implant (n = 4), 0.9% sodium chloride as placebo (n = 4) | s.c. single-use administration; the animals that showed estrus signs were ovariohysterectomized during the mid-luteal phase, and mature corpora lutea were collected | The expression of prostaglandin E2 receptors was significantly higher in the CL of deslorelin-treated bitches; the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor VEGFR1 increased significantly in CL | [47] |

| Bitches younger than 4.5 years (n = 32) | Client-owned | GnRH analog | 9.4 mg of deslorelin acetate implant (n = 5), 4.7 mg of deslorelin acetate implant (n = 4), 0.9% sodium chloride as placebo (n = 4) | 1st treatment: 4.7 mg, n = 20 and 9.4 mg, n = 12; subsequent treatments: 9.4 mg, n = 21 and 4.7 mg, n = 11; bitches had the implant for 0.5–11.3 years | Long-term side effects in 3 dogs, after more than five years of treatment, were persistent heat, ovarian tumors, and cystic endometrial hyperplasia; flare-up was an immediate side effect | [43] |

| Cross-breed prepubertal bitches 4.2 ± 0.6 months of age (n = 11) | Housed in indoor–outdoor runs with average of 12 h daylight exposure | GnRH analog | 4.7 mg Suprelorin implant (n = 3), 9.4 mg Suprelorin implant (n = 4), sodium chloride 0.9% (placebo) (n = 4) | s.c., animals were ovariohysterectomized before puberty or metestrus | All from the placebo group and two from Suprelorin implant came into estrus; no significant difference in serum P4 and E2 levels between the placebo and Suprelorin treatments | [57] |

| Healthy in anestrus, 20–35 kg, 7-year-old pure-breed bitches (n = 42) | - | GnRH analog and synthetic progestin | 10 mg of DA biocompatible implant, 2 mg/kg of MA slotted of 20 mg tablets, PL implant formulated as the inert matrix of DA without drug | s.c. DA and PL and MA oral administration; PL (n = 12) once; MA (n = 4) for 8 days; DA (n = 8) once; MA and DA-1 (n = 8): MA beginning one day before DA; MA and DA (n = 10): MA beginning 4 days before DA | Interestrous interval post-treatment of DA-treated bitches was longer than the PL-treated bitches; simultaneous administration of MA with DA did not seem to significantly prolong the effect of DA | [44] |

| Mixed-breed bitches in anestrus aged 5, 4, and 4 years with normal reproductive history and progesterone levels <1 ng/mL (n = 3) | - | GnRH analog and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor (trilostane (Vetoryl®)) | 4.7 mg of Suprelorin®, 10 mg/kg body weight of trilostane (Vetoryl®) | Vetoryl® 6 h before and in deslorelin implant application, and in at 6 and 9 h after; the Suprelorin® implant was introduced simultaneously with the second administration of Vetoryl® s.c. | The serum levels of LH, P4, cortisol, and E2 decreased through the first 4 administrations of Vetoryl®; P4 serum levels decreased, and 3 bitches developed signs of estrus or diestrus around day 16 after implantation of Suprelorin | [46] |

| Around 5 months of age, beagle bitches (n = 20, 10 per group) | - | GnRH agonist | 18.5 mg of azagly-nafarelin (Gonazon®) or placebo | s.c. in the umbilical region and were kept for 1 year | None of the bitches treated with Gonazon® displayed estrus or ovulation during the treatment, just after the implant was removed | [54] |

| 12–18 weeks old, mixed breeds, prepubertal bitches (n = 83) | - | GnRH analog | 4.7 mg of Suprelorin implant (n = 62), 1 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride (n = 21) | Implants were administered s.c. | The Suprelorin group had a delayed estrus compared to the PL (377 days vs. 217 days); after 24 months post-implantation, all bitches from both groups showed functional reproductive abilities | [45] |

| Sicilian hound female dogs (n = 24) | - | GnRH analog | 4.7 mg of DA implant; control: non-implanted animals | Treatment group: at 4.5, 9, and 13.5 months; control: ovariohysterectomized at 4.5 or 18 months | The estrus was suppressed in the treated group after the first implantation; E2 and P4 levels remained at baseline; there were no follicular structures | [50] |

| Adult healthy (n = 7) or with mammary neoplasia bitches (n = 3) in anestrus or diestrus | Absent of irregular estrus cycles and of prolonged or abnormal vulvar discharge | GnRH analog | 4.7 mg or 9.4 mg of DA implant | s.c., the treatment was repeated every 5 months depending on the dogs’ requirements | Bitches implanted during anestrus came in heat 4–15 days after treatment; the 9.4 mg implant had estrus inhibition for 11–14 months; the 4.7 mg implant appeared to perform for only 5 months; suppression of reproductive cyclicity was achieved in 60% of bitches for 1–4 years | [53] |

| Healthy adult 1–3-year-old greyhound bitches, in anestrus (n = 15) | - | GnRH analog | Deslorelin implant and 14 doses of 2 mg/kg MA (n = 5); placebo group untreated (n = 10) | Deslorelin implant on day 0; the MA group was treated orally daily from day −7 to 6. | In treated group, estrus signs were observed and plasma LH and E2 were lower | [58] |

| Prepubertal beagle dogs (n = 25, where half of them were female) | Controlled conditions and light exposure from 6:00 to 18 h | GnRH ethylamide | 100 μg of [D-Trp6, des-Gly-NH210] GnRH ethylamide dissolved in 0.9% NaCl-1% gelatin (n = 9 females); vehicle only for the control group (n = 8 females) | Subcutaneous injection daily for 23 months | Treatment inhibits sexual maturation and after cessation of it, normal pituitary–gonadal functions resume normally | [49] |

| Beagle bitches in anestrus aged 3–9 years (n = 5) | - | Synthetic progestin | 10 mg/kg bw MPA | s.c. administration at intervals of 4 weeks for a total of 13 times | No signs of estrus during the 12 months of treatment | [42] |

| Sexually mature female dogs in anestrus (n = 15) | - | Phytoestrogens | 600 μg of coumestrol per kg of bw diluted in 20 μL of DMSO (n = 5); commercial food biscuit was given as a placebo with 20 μL of DMSO (n = 5) | Single or administration in a dog food biscuit | Coumestrol increased serum E2 levels on days 21 and 28; the number of vaginal cells remained in anestrus bitches; DMSO: increased serum P4, vaginal anucleated superficial cells, and diestrus length | [51] |

| Sexually mature female dogs in estrus (n = 15) | - | Phytoestrogens | 600 μg of coumestrol per kg of bw diluted in 20 μL of DMSO (n = 6); commercial food biscuit was given as a placebo with 20 μL of DMSO (n = 5) | Single or administration in a dog food biscuit | In animals that ovulated, COU did not affect hormonal profiles; in contrast, animals that did not ovulate showed lower circulating P4 concentrations | [52] |

| Domestic purebred bitches in anestrus (n = 19) | - | GnRH analog + GnRH antagonists | DA 10 mg implant (n = 6), DA 10 mg + and 330 mg/kg of acyline as a lyophilized powder suspended in water (2 mg/mL) | DA administration s.c.; DA + acyline was implanted s.c. and 48 h later, acyline was administered s.c. | All bitches developed estrus for the first month; the interestrus intervals were not significantly different; 6 bitches had an estrus response and ovulated with DA administration | [59] |

| Postpubertal bitches in proestrus (n = 20) | - | GnRH antagonists | Respective volume of acyline 2.2 mg/mL suspension, 110 μg/kg of acyline (n = 6), 330 μg/kg of acyline (n = 8); placebo (n = 6) | Injection s.c. | Estrus cycles and ovulation of treated groups were interrupted efficiently and reversibly for about 3 days; there was not a significant difference between both doses and return to estrus periods | [60] |

| Mature (1–4 years old) and immature (6–7 months old) bitches, 4 months after the proestrus period (n = 24 and 3, respectively) | - | Synthetic progesterone | 4–12.5 mg/kg of chlormadinone acetate; 2–6.25 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg of chlormadinone acetate | Twice a year: chlormadinone acetate to mature bitches daily for 7 days.; oral administration of chlormadinone acetate to mature and immature bitches | Bitches with the twice-a-year treatment had no long-term effect on estrus prevention activity after the end of the treatment, compared to the once-a-week-treated, which had an effect for 1 year or longer | [56] |

| Mongrel bitches aged from 8–48 months (n = 25, divided randomly into 5 groups); anestrus approximately 5 months after the last estrus (n = 21), and the beginning of proestrus (n = 4) | - | Synthetic progesterone | 2.5, 5, 10, 25, or 30 mg/kg of CA and silastic silicone rubber with a coagulant implant | s.c. administration; experiment 1: 19 bitches with 2.5–10 mg/kg doses, the implants were left for 24 months; experiment 2: the implants were removed to 6 bitches, 3 of them were given doses of 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg, and implants were removed after 12, 12, and 17 months; the 3 bitches left were given a 10 mg/kg dose implant for 29, 28, and 48 months | Estrus was observed after 3–13 months of administration in bitches with 2.5 mg/kg dose, 13–15 months in 3/5 bitches with 5 mg/kg dose, and more than 24 months in bitches with doses of 10 mg/kg and more; bitches in experiment 2, given the 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg doses, came into estrus 4, 8, and 10 months and the second estrus after 10, 14, and 18 months after removing the implant, respectively | [55] |

| Age, Breed (n = Number of Animals) | Previous Treatment | Compound | Doses Administration | Administration Protocol | Main Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds That Regulate the CL Function Tested inFemale Dogs | ||||||

| Beagle bitches (n = 16, 6 per group), probably estrus | - | 3β-HSD inhibitor | 4.5 mg/kg of trilostane | Administered orally twice a day for seven days, beginning on day 11 (PIP, n = 6) or 31 days after ovulation (PDP, n = 6) | Trilostane decreased P4 plasma concentration, so plasma prolactin did not increase | [62] |

| 2–4-year-old beagle bitches in luteal phase (n = 33) (probably diestrus) | Maintained in individual cages under a 12 h light:12 h dark schedule | ALHS dopamine agonist (bromocriptine) | 10 mL of equine ALHS (n = 5, where 2 were pregnant and 3 non-pregnant), 0.1 mg/kg bw of bromocriptine (n = 11); normal horse serum in ALHS control group (n = 6, where 3 were pregnant and 3 non-pregnant) and 20% ethanol in saline for bromocriptine control group (n = 11) | Single i.m. injection of ALHS and its control, at day 42 of pregnancy or ovarian cycle; bromocriptine and control were injected i.m. daily for 6 days starting on day 8, 22, or 42 of pregnancy and day 42 of ovarian cycle of non-pregnant bitches | ALHS reduced P4 levels in all treated bitches by 24 h but returned levels on day 4 after injection; bromocriptine caused abrupt declines in P4 in all treated bitches at day 8 after injection | [61] |

| Mature, pregnant, and non-pregnant beagle bitches (n = 30) | Indoor–outdoor runs in groups (2–5) with natural light exposure | Cabergoline | Prolactin (375 μg/animal/injection) and cabergoline or LH (750 μg/animal/injection) and cabergoline; placebo: propylene glycol | Subcutaneous administration of cabergoline 30 days after LH surge (10 pregnant, 10 non-pregnant) | Plasma prolactin levels were suppressed, and so progesterone for 5 days and non-effect of LH was observed after cabergoline injection | [65] |

| Mixed-breed and -age (2–7 years) bitches in diestrus (n = 30) | - | Firocoxib |

Treatment group: 10 mg firocoxib/kg bw per day; control Group: placebo | Administration for 5, 10, 20, or 30 days from day 0 (the day of ovulation) | Decreased expression of 3β-HSD mRNA and protein, area of the luteal cell nuclei, P4 concentrations | [63] |

| Mixed-breed 2–7-year-old bitches in diestrus (n = 30) | - | Firocoxib |

10 mg/kg bw daily dose of firocoxib; untreated dogs served as controls | Ovariohysterectomies were performed on days 5, 10, 20, or 30 depending on the treatment group | Firocoxib decreased the mRNA expression of STAR protein, PGE2 synthase, and prolactin receptor | [64] |

| Middle-sized, mixed-breed, 2–7 years of age, diestrus (n = 37). | - | Firocoxib |

10 mg/kg body weight per day of firocoxib; control: PL | Oral administration for 5, 10, 20, and 30 days (first day of ovulation = day 0); bitches were ovariohysterectomized on the last day for collection of CL | Firocoxib inhibited cyclooxygenase 2/prostaglandin synthase 2, which caused PGE2 decrease, which suggests their matter in regulating CL | [66] |

| Age, Breed (n = Number of Animals) | Previous Treatment | Doses Administration | Administration Protocol | Main Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kisspeptin (KP) AdministrationTested in Female Dogs | |||||

| Adult 86 and 41 months of age, 14–15 kg bw beagle bitches in the follicular phase (n = 12) | Were housed in pairs in indoor–outdoor runs |

Experiment 1: 0.5

μg/kg bw of canine kisspeptin-10 (KP-10); experiment 2: 0.5 μg/kg body weight of canine KP-10 and an infusion with 50 μg/kg body weight per hour of p271 |

I.v. administration in the cephalic vein; in group 2, a continuous i.v. infusion with p271 was administered for 3 h in the cephalic vein, and canine KP-10, 2 h after the start of the p271 infusion | Canine KP-10 increased plasma LH concentration and peaked 10 min after administration; p271 did not alter the LH concentration nor lower the LH response to KP-10 | [67] |

|

Healthy, median age of 36–70-month-old beagle bitches, in anestrus (n = 12, 6 per group) | Housed in pairs in indoor–outdoor runs |

High-dosage group: 1–30

μg/kg canine KP-10; low-dosage group: 0–1 μg/kg canine KP-10 | 30 μg/kg and next doses were decreasing to 10, 5, 1, and 0 μg/kg or in the reverse order by the cephalic vein at weekly intervals during anestrus | LH secretion peaked 10 min after administration; high-dosage group increased the plasma levels of LH, E2, and FSH; low-dosage group: increase in LH plasma level | [69] |

|

Beagles, 8–12-month-old dogs in anestrus (n = 20) | - | 2.6 mL/kg of 30, 100, and 1000 μg/kg of KP-10 or sterile saline solution (control) once a day |

Daily i.v. for 14 consecutive days with a 14-day recovery period; necropsied 15 (n = 3 per group) and 29 days (n = 2) after 14-day dosing | Bitches remained in the anestrus phase | [70] |

| Beagle female dogs in anestrus (n = 13) | - | Control (n = 6): 0.5 μg/kg canine KP-10; antagonist experiments (n = 8): canine KP-10 and 50 μg/kg/h antagonists; 4 bitches received p271, p354, and p356; 2 bitches received p354 and p356; and 2 bitches received only p271 |

Continuous administration of KP-10 antagonists for 3 h via a catheter in the cephalic vein; two hours later, canine KP10 was administered i.v.; the time between testing of different antagonists was 5–15 days | None of these antagonists lowered the basal plasma LH concentration and none of the peptides lowered the KP10-induced LH response | [68] |

| Age, Breed (n = Number of Animals) | Previous Treatment | Doses Administration | Administration Protocol | Main Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other Contraceptive Methods Tested in Female Cats | |||||

| Domestic short-haired cats (Felis silvestris catus), nulliparous, sexually intact (main study n = 9, pilot study n = 3) | Physical examinations and blood tests | A single intramuscular injection of the AAV9 viral vector carrying the fcMISv2 transgene, which encodes feline anti-Müllerian hormone; low dose: 5 × 1012 vg/kg; high dose: 1 × 1013 vg/kg; control: empty vector AAV9 (5 × 1012 vp/kg) | The single injection was administered into the right caudal thigh muscle; two mating trials were conducted in which females were housed with a fertile male for 4 months per trial, 8 h per day, 5 days per week | All cats in the control group became pregnant and had offspring, while no AAV9-fcMISv2-treated cats became pregnant | [1] |

| Other Contraceptive Methods Tested in Female Dogs | |||||

| Clinically healthful, mixed-breed, reproductively adult anestrous female dogs (n = 26) | Checked for pregnancy by transabdominal ultrasound | Therapeutic ultrasound 1 MHz, 1.5 W/cm2 | Control (laparotomy) group (n = 6) and two treatment groups: 5- and 10-min treatment of ovaries with therapeutic ultrasound wave during laparotomy | Systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, decreased primordial follicles, and lower oocyte preservation score, suggesting ovarian damage and possible long-term subfertility | [72]. |

| Healthy female adult dogs, mixed-breed (n = 5) | General clinical evaluation | Dose variable according to ovarian diameter, calculated by ultrasound scan | Direct intra-ovarian injection of neutral zinc gluconate by laparotomy with G24 needle; monitoring for 28 days | Reduction in ovarian size, increase in atretic follicles, histological changes such as fibrosis and hemorrhage; without complete destruction of ovarian tissue | [71] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peña-Corona, S.I.; Vaquera-Guerrero, M.A.; Cerbón-Gutiérrez, J.; Chávez-Corona, J.I.; Iglesias-Reyes, A.E.; Sierra-Reséndiz, A.; Pérez-Rivero, J.J.; Retana-Márquez, S.; Vizcaino-Dorado, P.A.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation and Future Perspectives of Non-Surgical Contraceptive Methods in Female Cats and Dogs. Animals 2025, 15, 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101501

Peña-Corona SI, Vaquera-Guerrero MA, Cerbón-Gutiérrez J, Chávez-Corona JI, Iglesias-Reyes AE, Sierra-Reséndiz A, Pérez-Rivero JJ, Retana-Márquez S, Vizcaino-Dorado PA, Quintanar-Guerrero D, et al. Comprehensive Evaluation and Future Perspectives of Non-Surgical Contraceptive Methods in Female Cats and Dogs. Animals. 2025; 15(10):1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101501

Chicago/Turabian StylePeña-Corona, Sheila I., Melissa Aurea Vaquera-Guerrero, José Cerbón-Gutiérrez, Juan I. Chávez-Corona, Adrián E. Iglesias-Reyes, Alonso Sierra-Reséndiz, Juan José Pérez-Rivero, Socorro Retana-Márquez, Pablo Adrián Vizcaino-Dorado, David Quintanar-Guerrero, and et al. 2025. "Comprehensive Evaluation and Future Perspectives of Non-Surgical Contraceptive Methods in Female Cats and Dogs" Animals 15, no. 10: 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101501

APA StylePeña-Corona, S. I., Vaquera-Guerrero, M. A., Cerbón-Gutiérrez, J., Chávez-Corona, J. I., Iglesias-Reyes, A. E., Sierra-Reséndiz, A., Pérez-Rivero, J. J., Retana-Márquez, S., Vizcaino-Dorado, P. A., Quintanar-Guerrero, D., Leyva-Gómez, G., & Vargas-Estrada, D. (2025). Comprehensive Evaluation and Future Perspectives of Non-Surgical Contraceptive Methods in Female Cats and Dogs. Animals, 15(10), 1501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101501