Italians Can Resist Everything, Except Flat-Faced Dogs! †

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design and Distribution

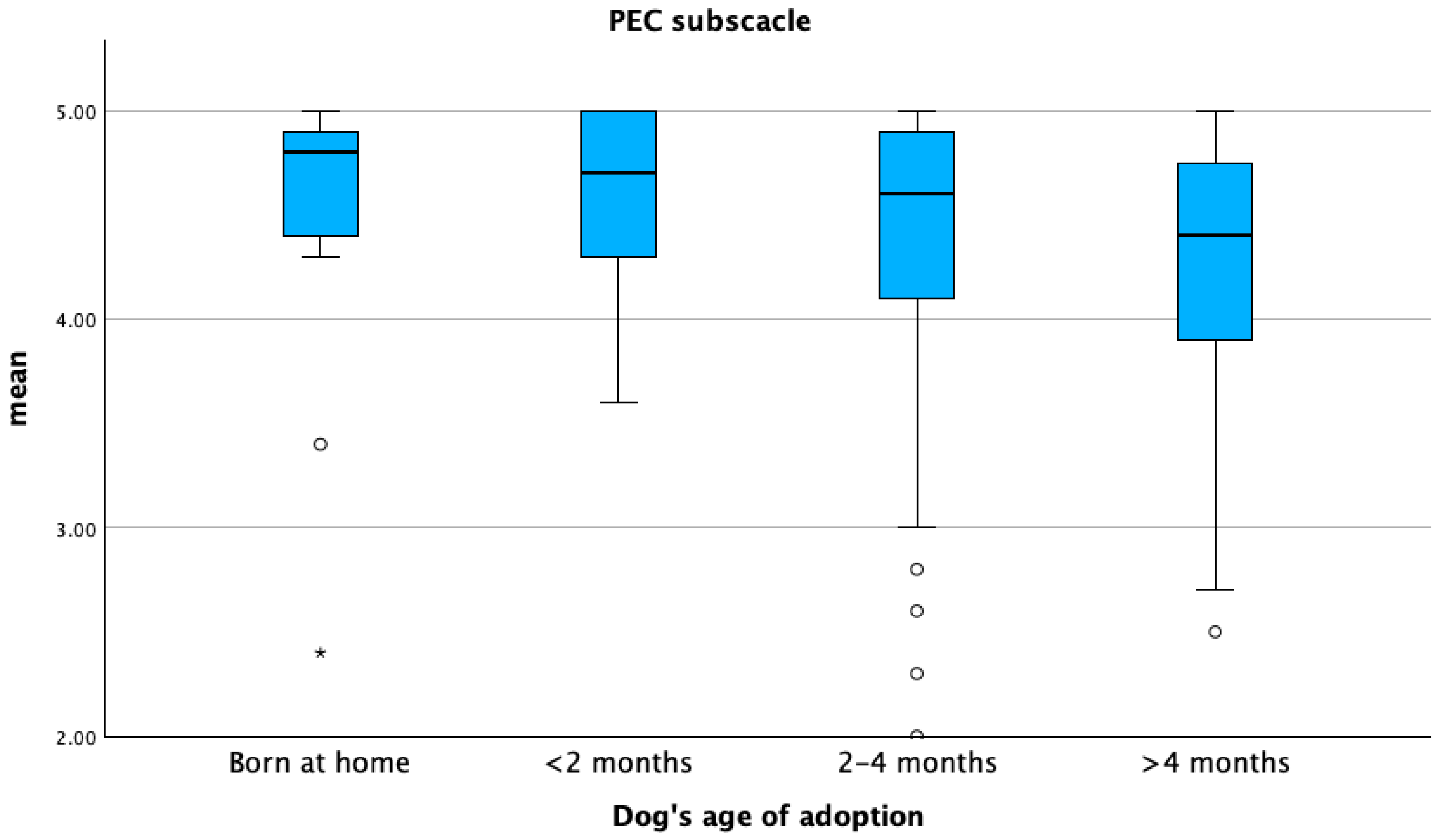

- Perceived emotional closeness (PEC, 9 items): this reflects social support, affection, bonding, psychological attachment, companionship, and unconditional love. High scores indicate stronger emotional bonding;

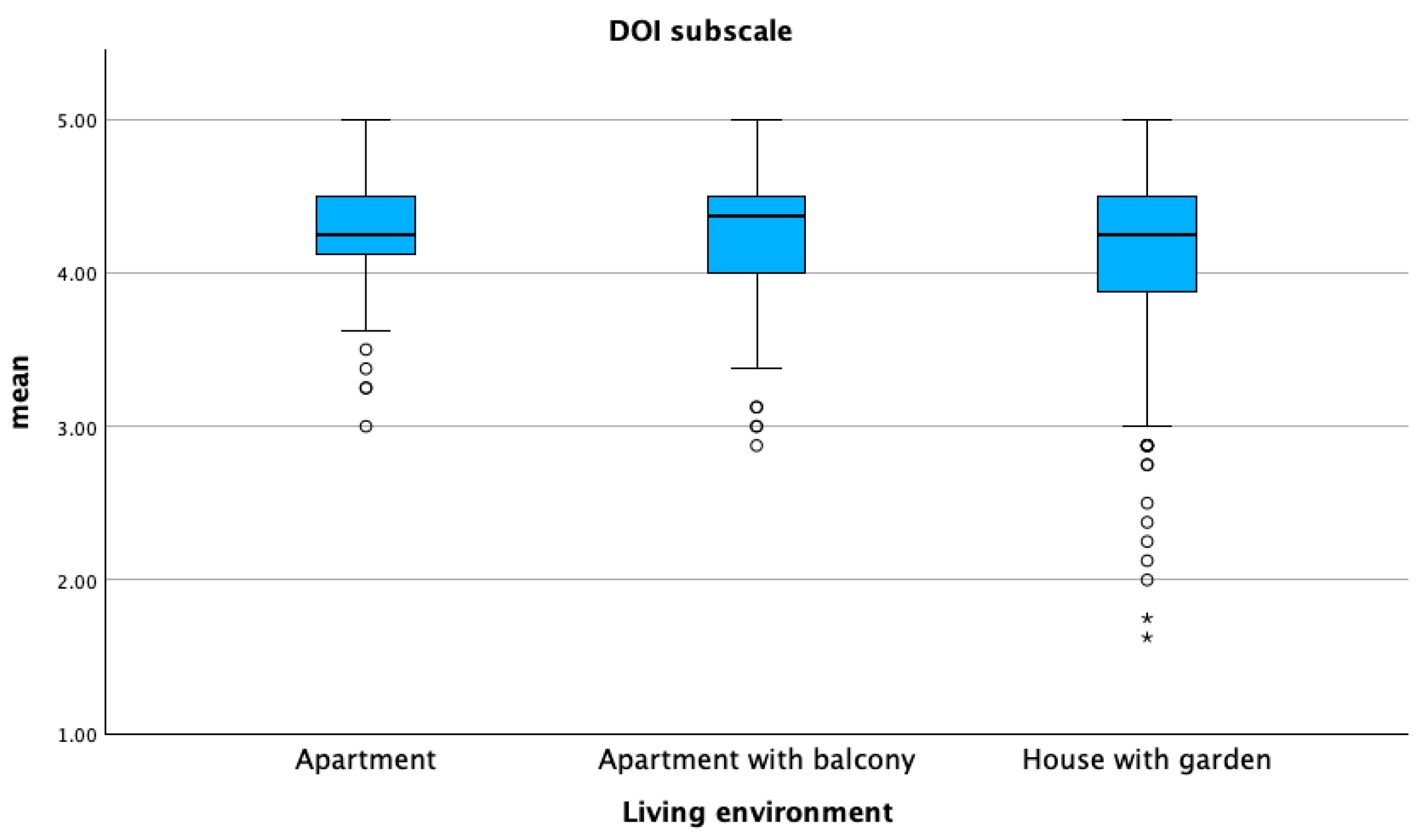

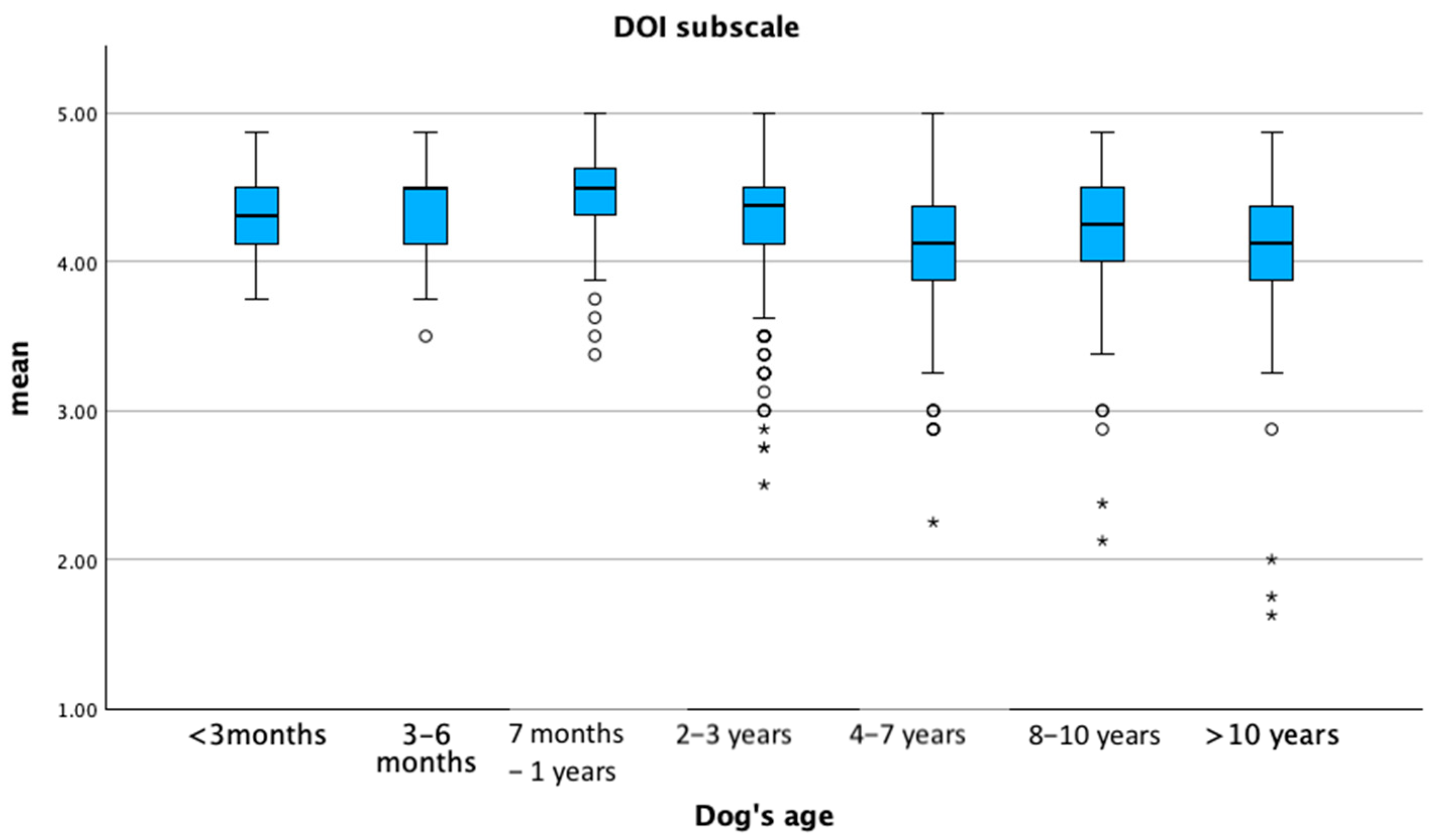

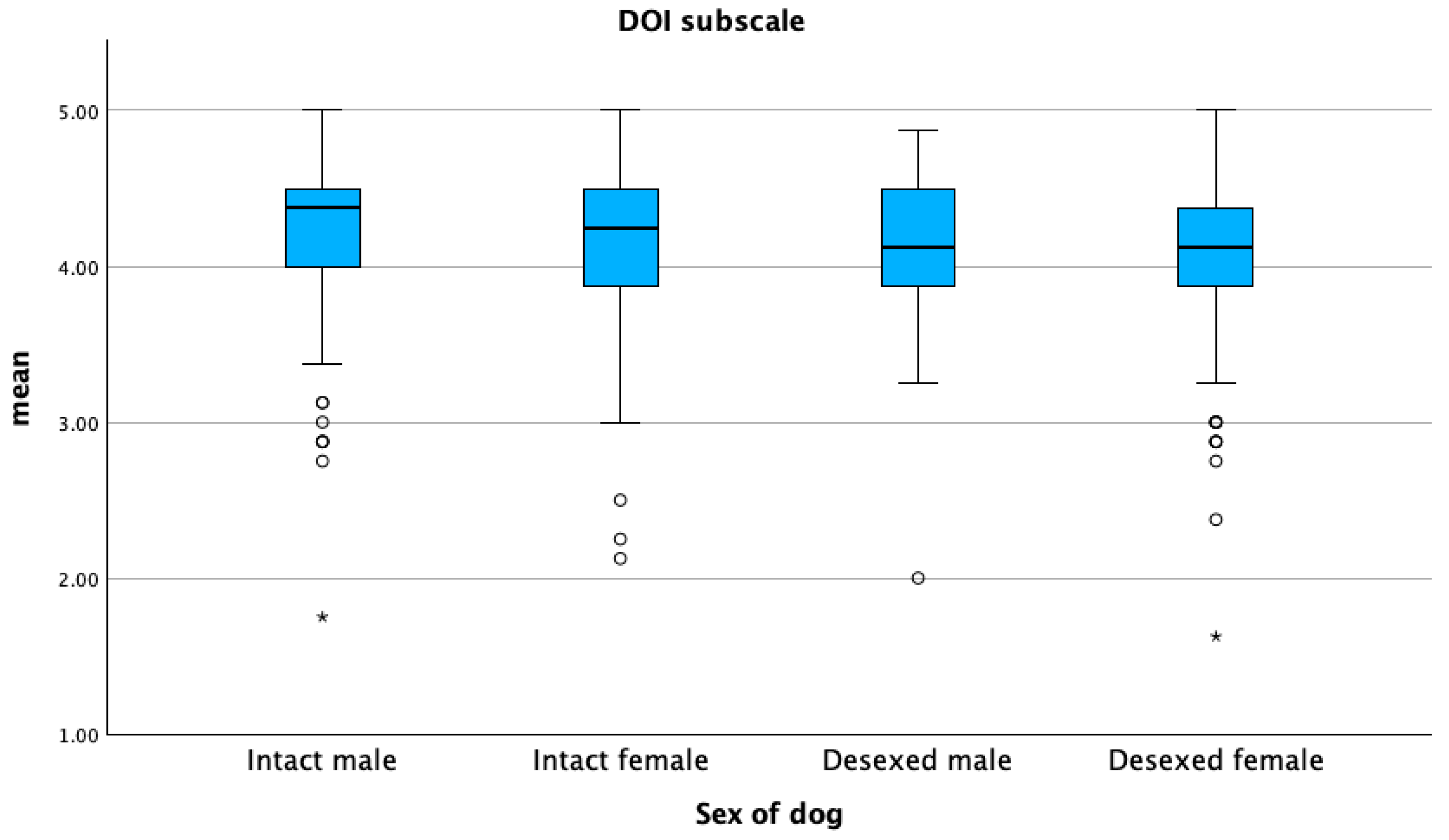

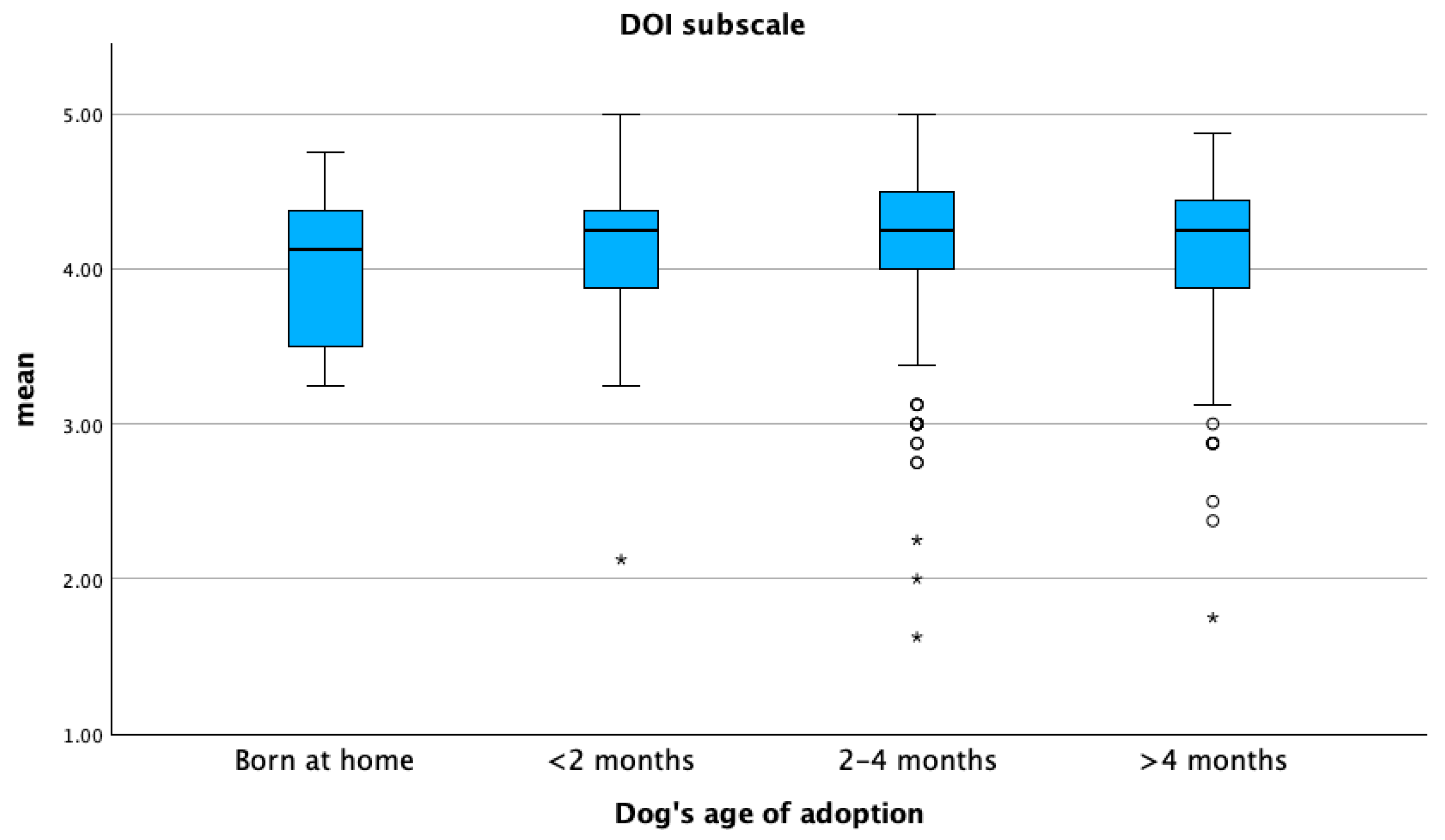

- The dog–owner interaction (DOI, 10 items): this sub-scale reflects activities related to the physical care of the pet, as well as to more intimate activities, such as kissing, cuddling, and hugging. High scores indicate more frequent and positive interactions;

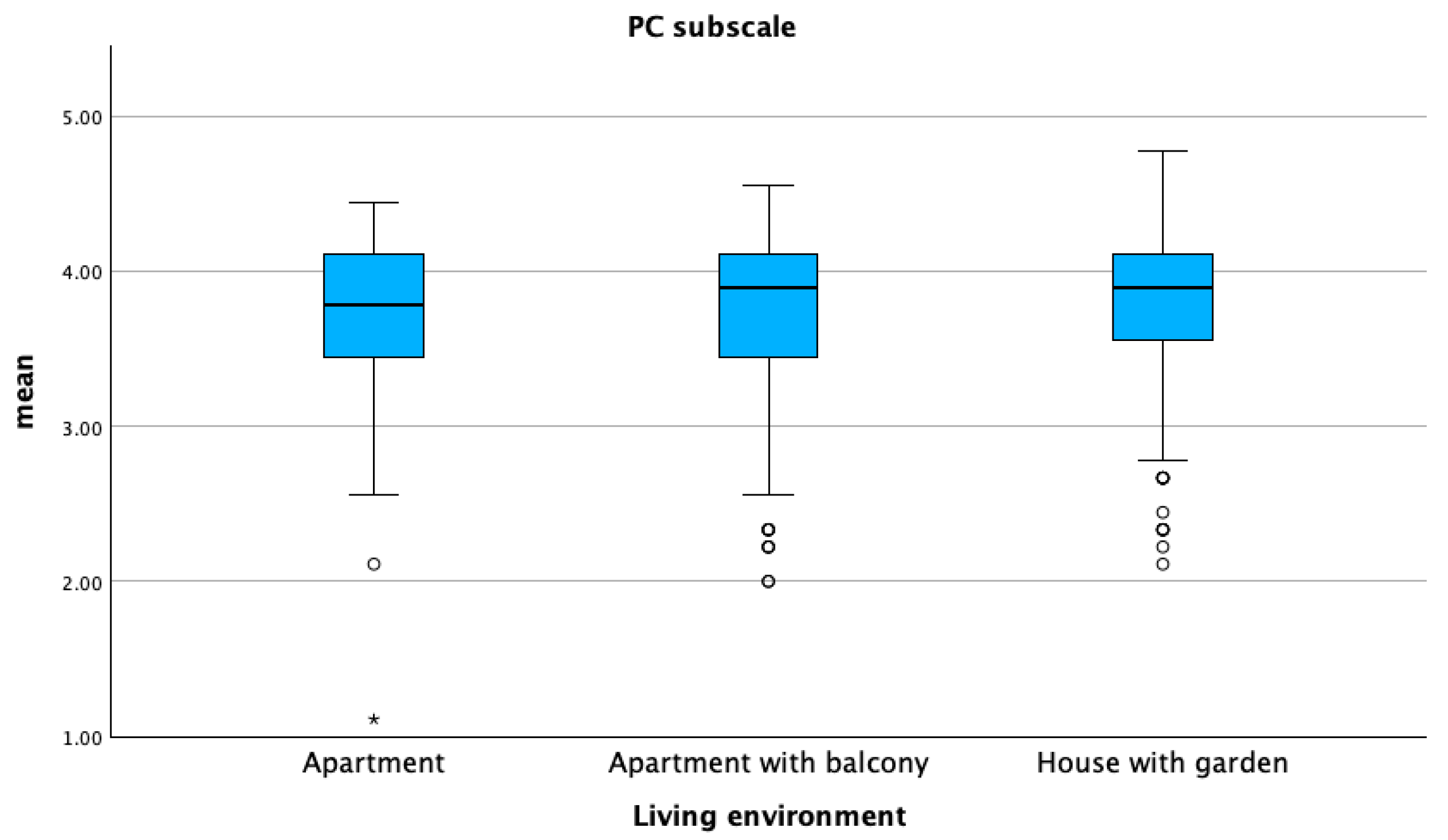

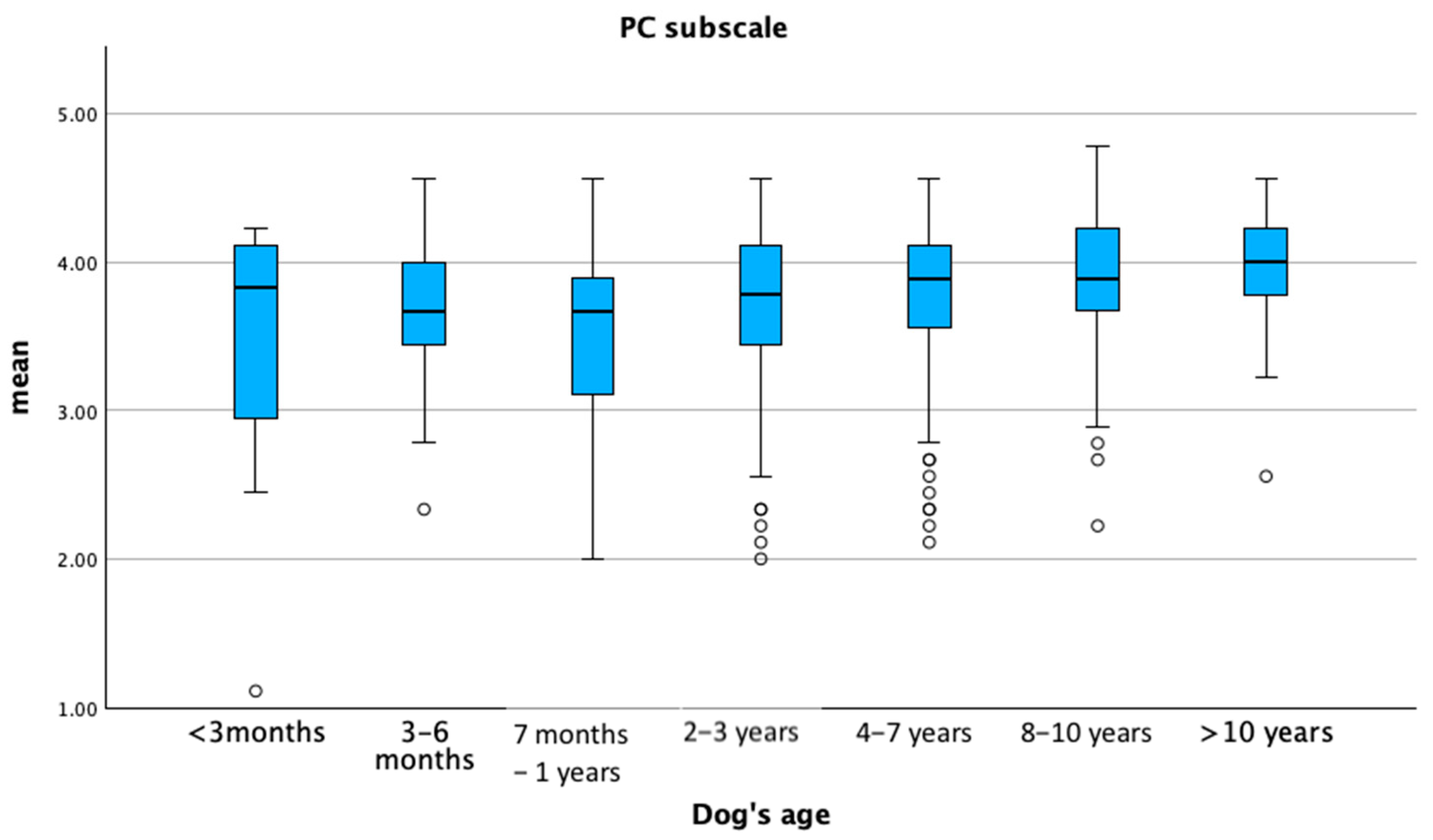

- Perceived cost (PC, 9 items): this captures financial, social, and emotional burdens. High scores indicate greater perceived burden and thus a less positive relationship.

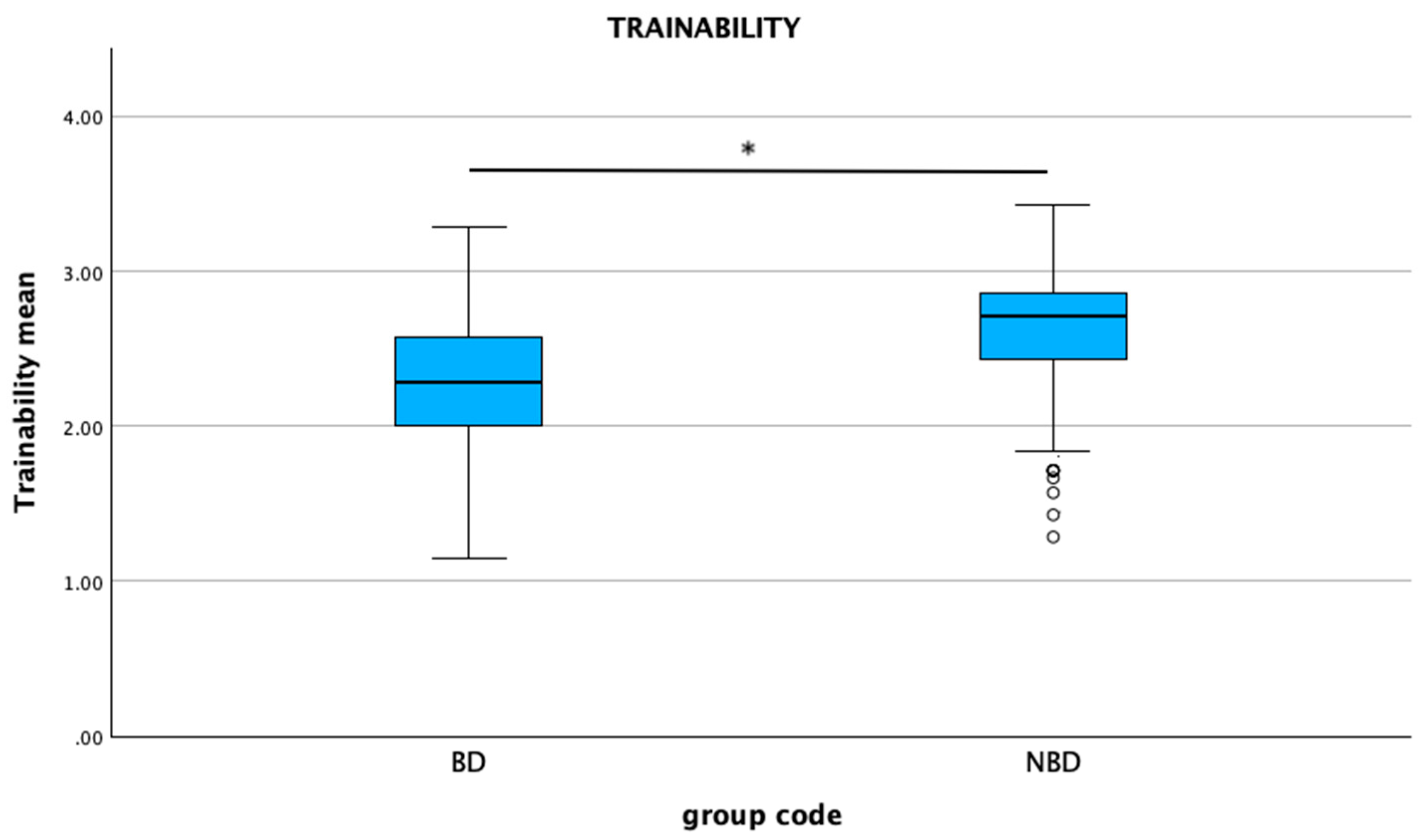

- Trainability (8 items): this evaluates the animal’s disposition to pay attention to its owner, follow simple instructions, learn quickly, retrieve objects, respond positively to correction, and ignore any distracting stimuli.

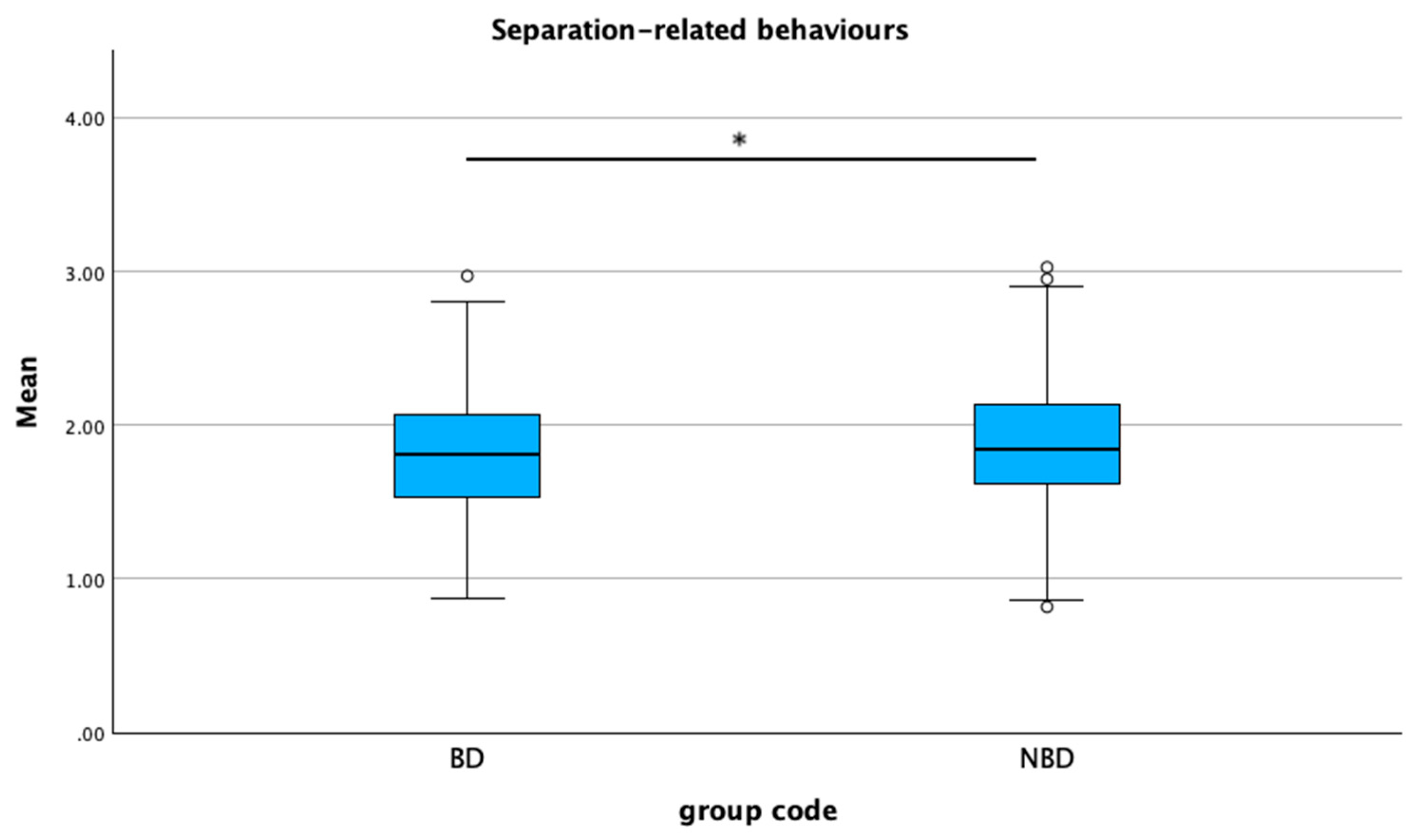

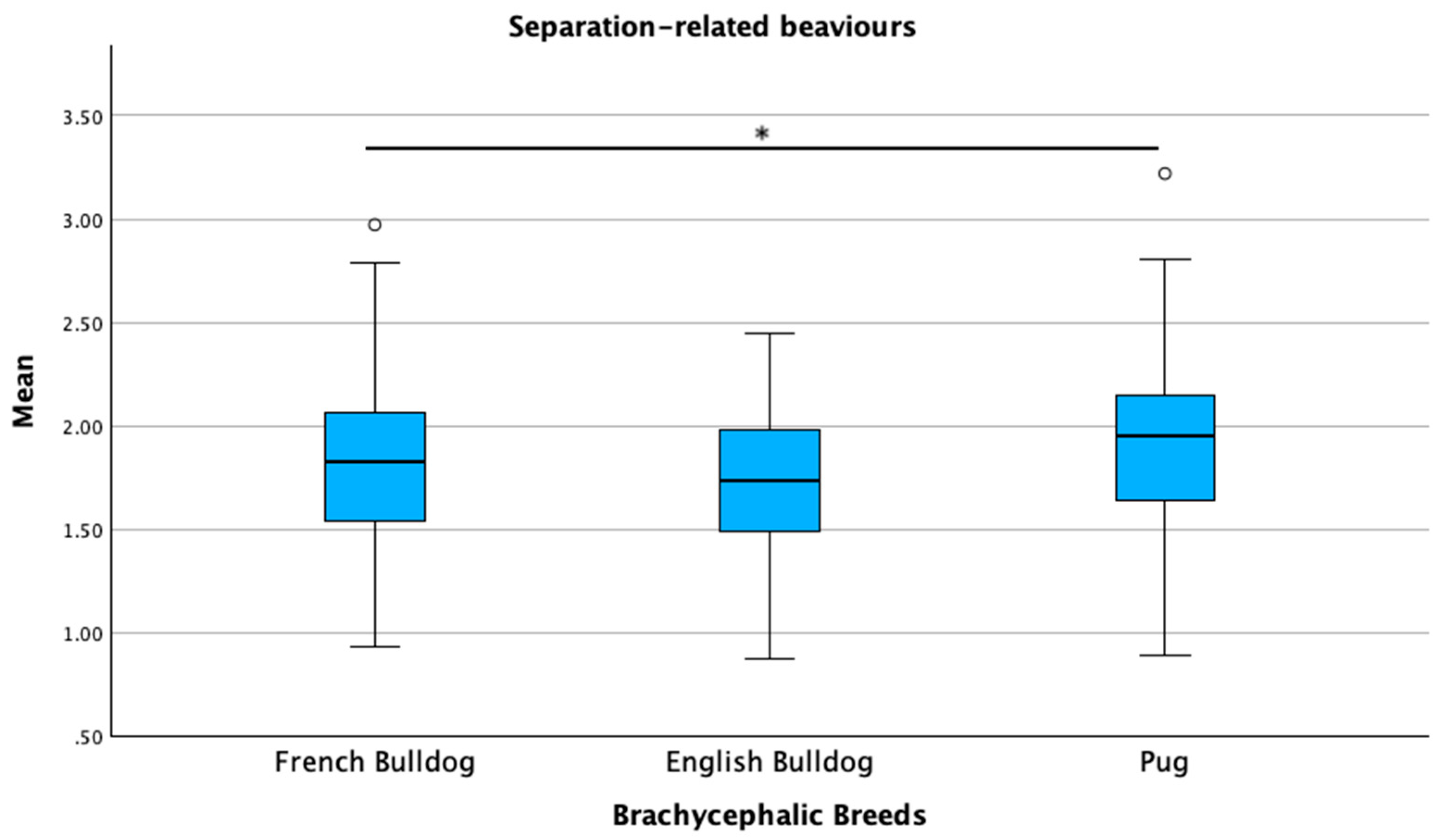

- Separation-related behavior (8 items): this assesses signs of anxiety when the dog is separated from its owner (i.e., vocalizing, destructiveness, restlessness, loss of appetite, trembling, and excessive salivation).

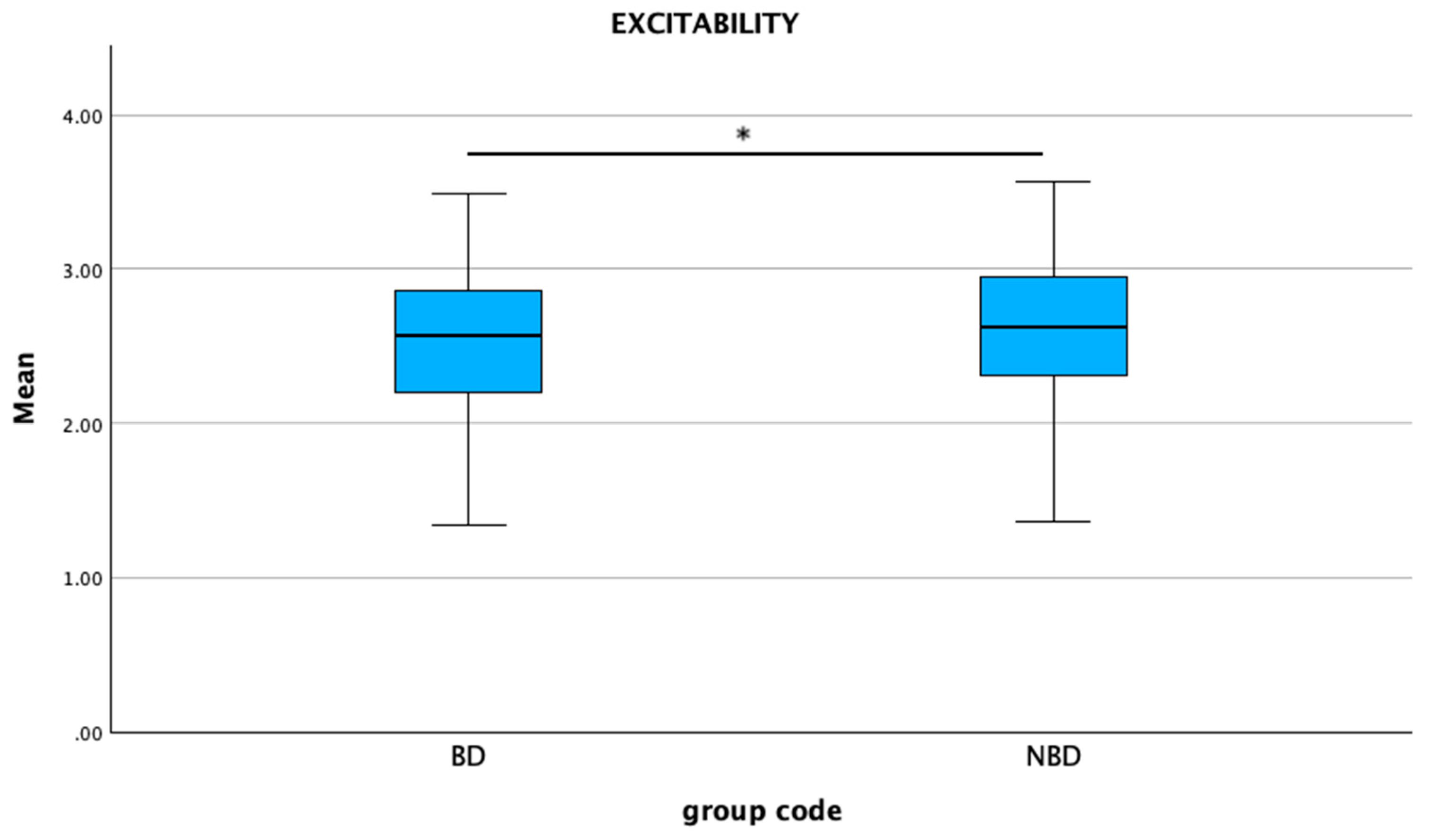

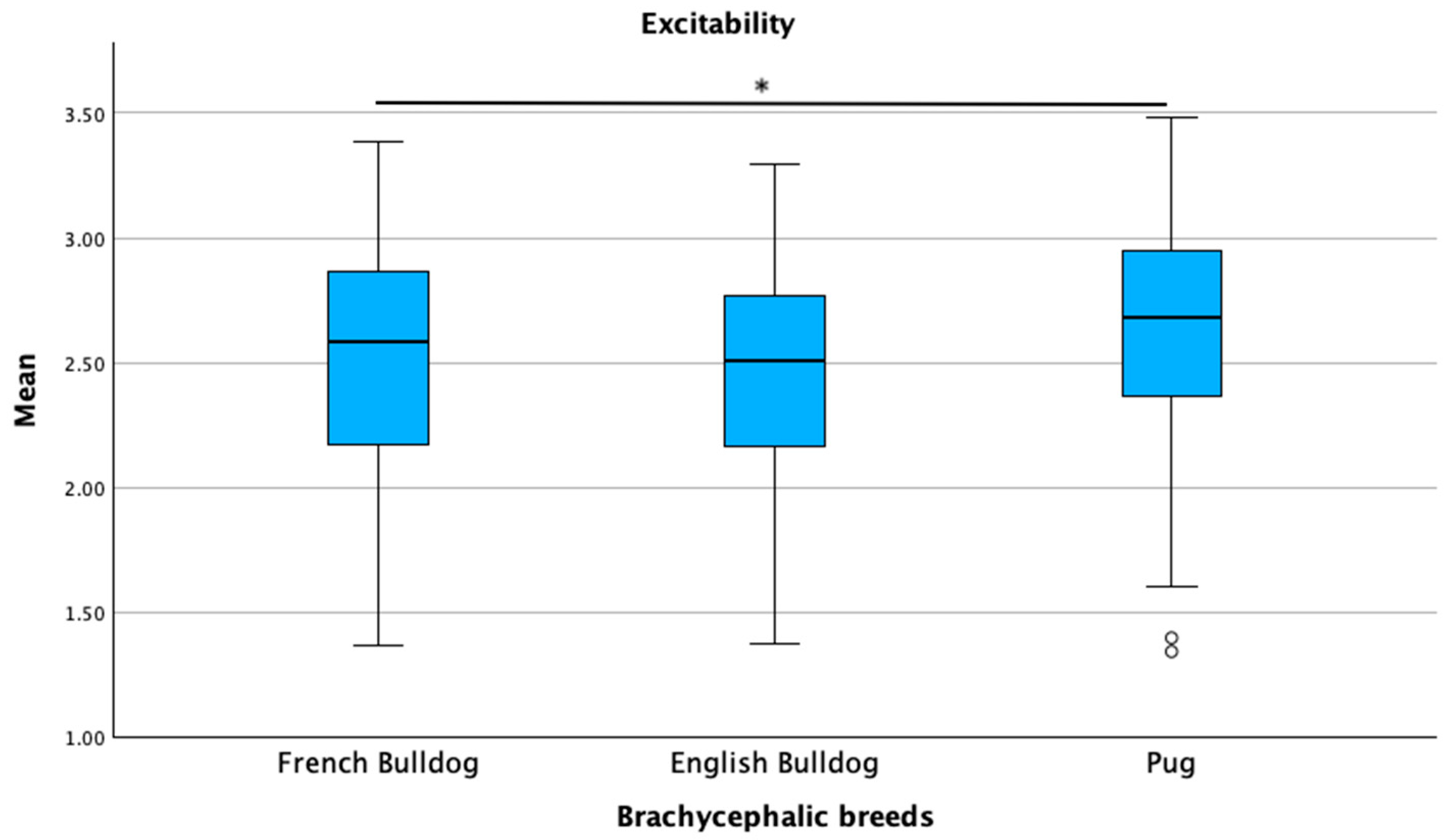

- Excitability (6 items): this measure strong reactions to potentially exciting or arousing events, such as going for walks or car trips, doorbells, the arrival of visitors, the owner arriving home, and the difficulty of settling down after such events.

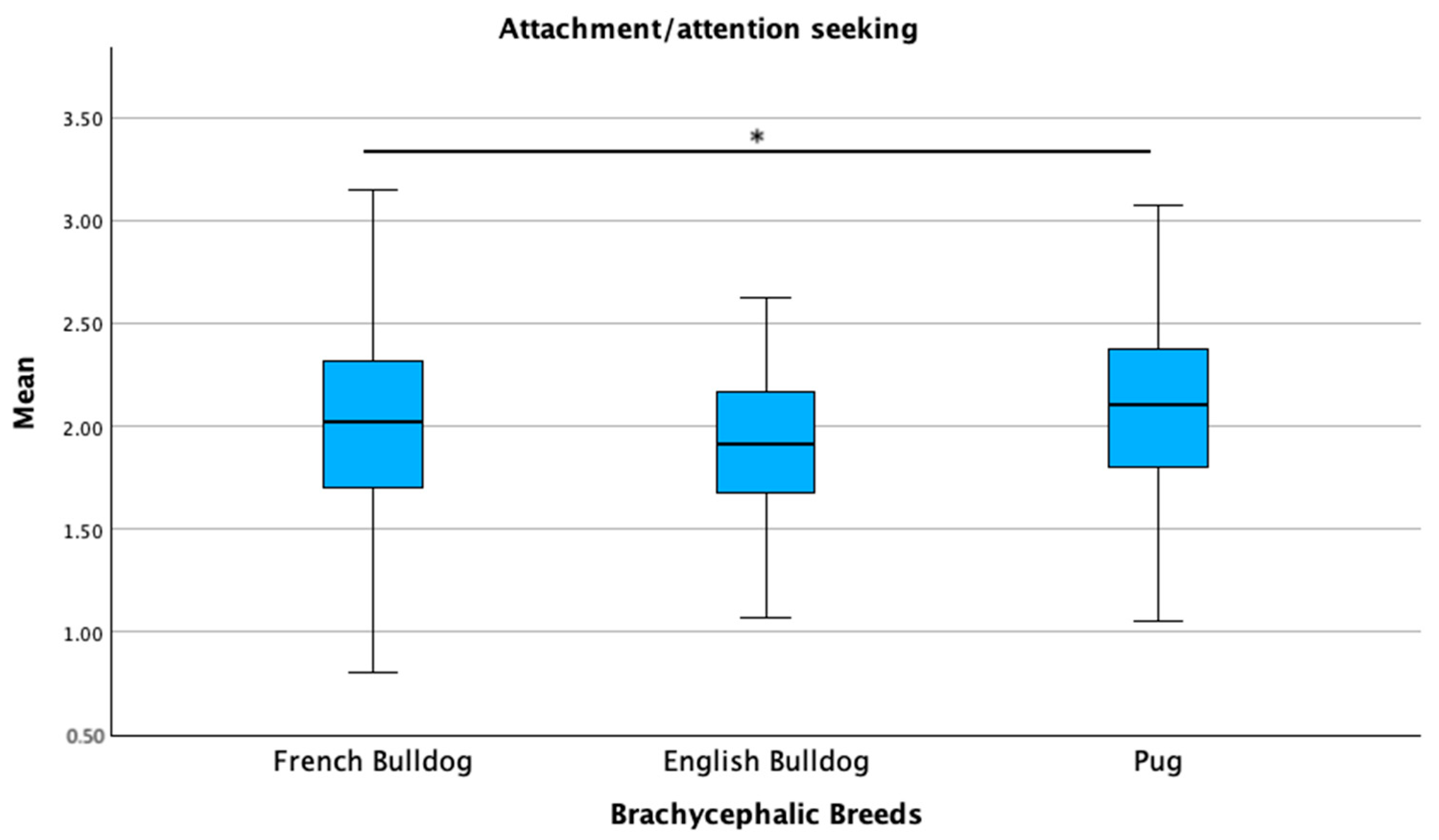

- Attachment or attention-seeking (6 items): this evaluates proximity-seeking behaviors, affection solicitation, and agitation when the owner interacts with others.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Section 1: Demographic Information

3.2. Section 2: Dog Demographics, Clinical History, and Owner Expectations

Brachycephalic Dog Owners

3.3. Section 3: DORS Scale

3.4. Section 4: C-BARQ

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Packer, R.M.A. Flat-Faced Fandom: Why Do People Love Brachycephalic Dogs and Keep Coming Back for More? In Health and Welfare of Brachycephalic (Flat-Faced) Companion Animals; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meola, S.D. Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2013, 28, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krainer, D.; Dupré, G. Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome. Small Anim. Soft Tissue Surg. 2023, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, J.C. Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 1992, 22, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Hendricks, A.; Tivers, M.S.; Burn, C.C. Impact of Facial Conformation on Canine Health: Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0137496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncet, C.M.; Dupre, G.P.; Freiche, V.G.; Estrada, M.M.; Poubanne, Y.A.; Bouvy, B.M. Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Tract Lesions in 73 Brachycephalic Dogs with Upper Respiratory Syndrome. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2005, 46, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, B.M.; Rutherford, L.; Perridge, D.J.; Ter Haar, G. Relationship between Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome and Gastrointestinal Signs in Three Breeds of Dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 59, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratschke, K. Current Thinking about Brachycephalic Syndrome: More than Just Airways. Companion Anim. 2014, 19, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Hendricks, A.; Burn, C.C. Impact of Facial Conformation on Canine Health: Corneal Ulceration. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebbag, L.; Sanchez, R.F. The Pandemic of Ocular Surface Disease in Brachycephalic Dogs: The Brachycephalic Ocular Syndrome. Vet. Ophthalmol. 2023, 26, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbrown-Hughes, D. Brachycephalic Ocular Syndrome in Dogs. Companion Anim. 2021, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Jackson, C.; Guy, J.H.; Church, D.B.; McGreevy, P.D.; Thomson, P.C.; Brodbelt, D.C. Epidemiological Associations between Brachycephaly and Upper Respiratory Tract Disorders in Dogs Attending Veterinary Practices in England. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 2015, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobi, S.; Barrs, V.R.; Bęczkowski, P.M. Dermatological Problems of Brachycephalic Dogs. Animals 2023, 13, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, L.; Diesel, G.; Summers, J.F.; McGreevy, P.D.; Collins, L.M. Inherited Defects in Pedigree Dogs. Part 1: Disorders Related to Breed Standards. Vet. J. 2009, 182, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.C.; Troconis, E.L.; Kalmar, L.; Price, D.J.; Wright, H.E.; Adams, V.J.; Sargan, D.R.; Ladlow, J.F. Conformational Risk Factors of Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS) in Pugs, French Bulldogs, and Bulldogs. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Jacobson, D.M.; Cox, M.D.; Carlson, M.D. Caregiver Burden in Owners of a Sick Companion Animal: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, R.M.A.; O’Neill, D.G.; Fletcher, F.; Farnworth, M.J. Come for the Looks, Stay for the Personality? A Mixed Methods Investigation of Reacquisition and Owner Recommendation of Bulldogs, French Bulldogs and Pugs. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, P.; Howell, T.J.; Brown, C.; Bennett, P.C. The Canine Cuteness Effect: Owner-Perceived Cuteness as a Predictor of Human–Dog Relationship Quality. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S.; Packer, R.M.A.; McGreevy, P.D.; Coombe, E.; Mendl, E.; Neville, V. That Brachycephalic Look: Infant-like Facial Appearance in Short-Muzzled Dog Breeds. Anim. Welf. 2023, 32, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berteselli, G.V.; Palestrini, C.; Scarpazza, F.; Barbieri, S.; Prato-Previde, E.; Cannas, S. Flat-Faced or Non-Flat-Faced Cats? That Is the Question. Animals 2023, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Hendricks, A.; Burn, C.C. Do Dog Owners Perceive the Clinical Signs Related to Conformational Inherited Disorders as ‘Normal’ for the Breed? A Potential Constraint to Improving Canine Welfare. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgi, M.; Cirulli, F. Pet Face: Mechanisms Underlying Human-Animal Relationships. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 180138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandøe, P.; Kondrup, S.V.; Bennett, P.C.; Forkman, B.; Meyer, I.; Proschowsky, H.F.; Serpell, J.A.; Lund, T.B. Why Do People Buy Dogs with Potential Welfare Problems Related to Extreme Conformation and Inherited Disease? A Representative Study of Danish Owners of Four Small Dog Breeds. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirlanda, S.; Acerbi, A.; Herzog, H.; Serpell, J.A. Fashion vs. Function in Cultural Evolution: The Case of Dog Breed Popularity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; O’Neill, D.G.; Fletcher, F.; Farnworth, M.J. Great Expectations, Inconvenient Truths, and the Paradoxes of the Dog-Owner Relationship for Owners of Brachycephalic Dogs. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, D.D.; Freemantle, R.; Jeffery, A.; Tivers, M.S. Impact of an Educational Intervention on Public Perception of Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome in Brachycephalic Dogs. Vet. Rec. 2022, 190, e1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Wade, A.; Neufuss, J. Nothing Could Put Me Off: Assessing the Prevalence and Risk Factors for Perceptual Barriers to Improving the Welfare of Brachycephalic Dogs. Pets 2024, 1, 458–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berteselli, G.V.; Palestrini, C.; Prato Previde, E.; Cannas, S. Differences in the Ownership of Brachycephalic Dog Breeds and Non- Brachycephalic Dog Breeds. Preliminary Results. Dog Behav. 2023, 9, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, T.J.; Bowen, J.; Fatjó, J.; Calvo, P.; Holloway, A.; Bennett, P.C. Development of the Cat-Owner Relationship Scale (CORS). Behav. Process. 2017, 141, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.; Serpell, J.A. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire for Measuring Behavior and Temperament Traits in Pet Dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A. Gender Differences in Human-Animal Interactions: A Review. Anthrozoos 2007, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostol, L.; Rebega, O.L.; Miclea, M. Psychological and Socio-Demographic Predictors of Attitudes toward Animals. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 78, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, K.; Kuhne, F.; Kramer, M.; Hackbarth, H. People’s Perception of Brachycephalic Breeds and Breed-Related Welfare Problems in Germany. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 33, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.; Marston, L.C.; Bennett, P.C. Describing the Ideal Australian Companion Dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diverio, S.; Boccini, B.; Menchetti, L.; Bennett, P.C. The Italian Perception of the Ideal Companion Dog. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 12, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Murphy, D.; Farnworth, M.J. Purchasing Popular Purebreds: Investigating the Influence of Breed-Type on the Pre-Purchase Motivations and Behaviour of Dog Owners. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Cox, M.D.; Jacobson, D.M.; Albers, A.L.; Carlson, M.D. Assessment of Caregiver Burden and Associations with Psychosocial Function, Veterinary Service Use, and Factors Related to Treatment Plan Adherence among Owners of Dogs and Cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2019, 254, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; O’Neill, D.G. Health and Welfare of Brachycephalic (Flat-Faced) Companion Animals; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Mills, J. An Introduction to Cognitive Dissonance Theory and an Overview of Current Perspectives on the Theory. In Cognitive Dissonance: Reexamining a Pivotal Theory in Psychology, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino-Montecinos, S.; Björklund, F.; Lindholm, T. A General Model of Dissonance Reduction: Unifying Past Accounts via an Emotion Regulation Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 540081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlf, V.I.; Bennett, P.C.; Toukhsati, S.; Coleman, G. Beliefs Underlying Dog Owners’ Health Care Behaviors: Results from a Large, Self-Selected, Internet Sample. Anthrozoos 2012, 25, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgi, M.; Cogliati-Dezza, I.; Brelsford, V.; Meints, K.; Cirulli, F. Baby Schema in Human and Animal Faces Induces Cuteness Perception and Gaze Allocation in Children. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K. Die Angeborenen Formen Möglicher Erfahrung. Z. Tierpsychol. 1943, 5, 235–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glocker, M.L.; Langleben, D.D.; Ruparel, K.; Loughead, J.W.; Gur, R.C.; Sachser, N. Baby Schema in Infant Faces Induces Cuteness Perception and Motivation for Caretaking in Adults. Ethology 2009, 115, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; McGreevy, P.; Kara, E.; Miklósi, Á. Effects of Selection for Cooperation and Attention in Dogs. Behav. Brain Funct. 2009, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, Z.; Szabó, D.; Deés, A.; Kubinyi, E. Shorter Headed Dogs, Visually Cooperative Breeds, Younger and Playful Dogs Form Eye Contact Faster with an Unfamiliar Human. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.D.; Georgevsky, D.; Carrasco, J.; Valenzuela, M.; Duffy, D.L.; Serpell, J.A. Dog Behavior Co-Varies with Height, Bodyweight and Skull Shape. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, Z.; Iotchev, I.B.; Kubinyi, E. Sex, Skull Length, Breed, and Age Predict How Dogs Look at Faces of Humans and Conspecifics. Anim. Cogn. 2018, 21, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.; Grassi, T.D.; Harman, A.M. A Strong Correlation Exists between the Distribution of Retinal Ganglion Cells and Nose Length in the Dog. Brain Behav. Evol. 2003, 63, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, Z.; Kubinyi, E. The Brachycephalic Paradox: The Relationship between Attitudes, Demography, Personality, Health Awareness, and Dog-Human Eye Contact. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 264, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téglás, E.; Gergely, A.; Kupán, K.; Miklósi, Á.; Topál, J. Dogs’ Gaze Following Is Tuned to Human Communicative Signals. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincat, B.L.; McGreevy, P.D.; Bowell, V.A.; Packer, R.M.A. Who’s Getting a Head Start? Mesocephalic Dogs in Still Images Are Attributed More Positively Valenced Emotions Than Dogs of Other Cephalic Index Groups. Animals 2021, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helton, W.S. Cephalic Index and Perceived Dog Trainability. Behav. Processes 2009, 82, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdek, L.A. Pet Dogs as Attachment Figures. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2008, 25, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, G.; Dodman, N.H. Risk Factors and Behaviors Associated with Separation Anxiety in Dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 219, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, J.; Monton, S. Preferences for Infant Facial Features in Pet Dogs and Cats. Ethology 2011, 117, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzano, A.; Lauria, C.; Ducci, M.; Sighieri, C. Dog Attention and Cooperation with the Owner: Preliminary Results about Brachycephalic Dogs. Dog Behav. 2015, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, J.M.; Bennett, P.C.; Coleman, G.J. A Refinement and Validation of the Monash Canine Personality Questionnaire (MCPQ). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 116, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn-Mølby, E.M.; Sindahl, L.; Saxmose Nielsen, S.; Bruun, C.S.; Sandøe, P.; Fredholm, M. Breeding French Bulldogs so That They Breathe Well—A Long Way to Go. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.; Hartog, J.; Vijverberg, W. Self-Selection Bias in Estimated Wage Premiums for Earnings Risk. Empir. Econ. 2009, 37, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, E.K.; Kogan, L.R. Owners’ Attitudes, Knowledge, and Care Practices: Exploring the Implications for Domestic Cat Behavior and Welfare in the Home. Animals 2019, 9, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.; García, E.; Darder, P.; Argüelles, J.; Fatjó, J. The Effects of the Spanish COVID-19 Lockdown on People, Their Pets, and the Human-Animal Bond. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 40, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christley, R.M.; Murray, J.K.; Anderson, K.L.; Buckland, E.L.; Casey, R.A.; Harvey, N.D.; Harris, L.; Holland, K.E.; McMillan, K.M.; Mead, R.; et al. Impact of the First COVID-19 Lockdown on Management of Pet Dogs in the UK. Animals 2020, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NBDOs | BDOs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° | % | N° | % | ||

| Sex | Female | 365 | 89.5% | 280 | 87.5% |

| Male | 38 | 9.3% | 35 | 10.9% | |

| I prefer not to specify | 5 | 1.2% | 5 | 1.6% | |

| Age * | 18–30 years | 149 | 36.5% | 66 | 20.6% |

| 31–44 years | 153 | 37.5% | 127 | 39.7% | |

| 45–54 years | 64 | 15.7% | 100 | 31.3% | |

| 55–64 years | 37 | 9.1% | 21 | 6.6% | |

| 65–74 years | 3 | 0.7% | 3 | 0.9% | |

| >75 years | 2 | 0.5% | 3 | 0.9% | |

| Environment * | Apartment | 118 | 28.9% | 143 | 44.7% |

| apartment with a balcony | 249 | 61.0% | 137 | 42.8% | |

| semi-detached or detached house | 103 | 41.2% | 91 | 32.9% | |

| Education level * | middle or secondary school | 212 | 52% | 206 | 64.4% |

| undergraduate or post-graduate degree | 196 | 48% | 114 | 35.6% | |

| People in the household | 1 | 48 | 11.8% | 35 | 10.9% |

| 2 | 170 | 41.7% | 121 | 37.8% | |

| 3 | 100 | 24.5% | 86 | 26.9% | |

| 4 | 73 | 17.9% | 58 | 18.1% | |

| 5 | 11 | 2.7% | 16 | 5% | |

| >5 | 6 | 1.5% | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Children in the household | No | 217 | 53.9% | 127 | 39.7% |

| Yes | 191 | 46.1% | 193 | 60.3% | |

| Previously * owned a dog | No | 68 | 16.7% | 90 | 28.1% |

| Yes | 340 | 83.3% | 230 | 71.9% | |

| NBDOs | BDOs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° | % | N° | % | ||

| Age * | Less than 3 months | 4 | 1% | 4 | 1.3% |

| 3–6 months | 10 | 2.5% | 23 | 7.2% | |

| 7 months–1 year | 13 | 3.2% | 34 | 10.6% | |

| 2–3 years | 131 | 32.1% | 116 | 36.3% | |

| 4–7 years | 120 | 29.4% | 87 | 27.2% | |

| 8–10 years | 74 | 18.1% | 35 | 10.9% | |

| More than 10 years | 56 | 13.7% | 21 | 6.6% | |

| Sex * | Intact male | 161 | 39.5% | 161 | 50.3% |

| Intact female | 114 | 26.9% | 69 | 21.6% | |

| Desexed male | 35 | 8.6% | 15 | 4.7.% | |

| Desexed female | 98 | 24% | 75 | 23.4% | |

| Age at acquisition * | Born at home | 11 | 2.7% | 2 | 0.6% |

| Less than 2 months | 27 | 6.6% | 14 | 4.4% | |

| 2–4 months | 291 | 71.3% | 252 | 78.8% | |

| More than 4 months | 79 | 19.4% | 52 | 16.3% | |

| Source * | Certified breeder (recognized by the Italian Authority) | 196 | 48% | 137 | 42.8% |

| Non-certified breeder | 22 | 5.4% | 48 | 15% | |

| Private/born at home | 106 | 26.0% | 104 | 32.5% | |

| Rescue | 67 | 16.4% | 13 | 4.1% | |

| Stray | 15 | 3.7% | 3 | 0.9% | |

| Other (Internet, shops, etc.) | 2 | 0.5% | 15 | 4.7% | |

| NBDOs | BDOs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° | % | N° | % | ||

| Veterinary check-ups * | never | 74 | 18.1% | 65 | 20.3% |

| 1 time per year | 241 | 59.1% | 82 | 25.6% | |

| 2–3 times for year | 69 | 16.9% | 85 | 26.6% | |

| 4–5 times per year | 19 | 4.7% | 43 | 13.4% | |

| > 5 times per year | 5 | 1.2% | 45 | 14.9% | |

| Brachycephalic breeds suffer more than others | Yes | 315 | 77.2% | 263 | 82.2% |

| No | 93 | 22.8% | 57 | 17.8% | |

| Brachycephalic breeds have more problems than others | Yes | 329 | 80.6% | 269 | 84.1% |

| No | 79 | 19.4% | 51 | 15.9% | |

| When your dog interacts with other dogs, what generally happens? * | Interact normally | 246 | 60.3% | 190 | 59.4% |

| Ignore each other | 47 | 11.5% | 42 | 13.1% | |

| The other dog attacks mine | 15 | 3.7 | 40 | 12.5% | |

| My dog attacks the other dog | 46 | 11.3 | 29 | 9.1% | |

| Other | 54 | 13.2% | 19 | 5.9% | |

| Satisfaction with veterinary expenses | Less than expected | 84 | 20.6% | 73 | 23.0% |

| Meets expectations | 214 | 52.5% | 156 | 49.1% | |

| More than expected | 110 | 27.0% | 89 | 28.0% | |

| Satisfaction with the activity level of your dog * | Less than expected | 58 | 14.2% | 51 | 16.0% |

| Meets expectations | 242 | 59.3% | 213 | 66.8.0% | |

| More than expected | 108 | 26.5% | 55 | 17.2.0% | |

| Satisfaction with interactions (play, cuddle requests, etc.) * | Less than expected | 46 | 11.3% | 15 | 4.7% |

| Meets expectations | 220 | 53.9% | 165 | 51.9% | |

| More than expected | 142 | 34.8% | 138 | 43.4% | |

| Satisfaction with general behavior * | Better than expected | 152 | 37.3% | 168 | 52.5% |

| Meets expectations | 177 | 43.4% | 127 | 39.7% | |

| Worse than expected | 79 | 19.4% | 25 | 7.8% | |

| BDOs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N° | % | ||

| Symptoms during and after meals | Vomiting | 36 | 11.3% |

| Choking | 26 | 8.1% | |

| Difficulty breathing | 39 | 12.2% | |

| Regurgitation | 63 | 19.7% | |

| Symptoms during sleeping | Snoring | 200 | 62.3% |

| Changing positions | 98 | 30.6% | |

| Chin in an elevated position | 65 | 20.3% | |

| Open mouth breathing | 43 | 13.4% | |

| Apnea | 25 | 7.8% | |

| Other symptoms | Epiphora | 88 | 27.5% |

| Noisy breathing | 123 | 38.4% | |

| Breathing distress after activity | 206 | 64.4% | |

| Coughing | 28 | 8.8% | |

| Breathing distress in hot climatic conditions | 182 | 56.9% | |

| Heat intolerance | 6 | 1.9% | |

| Veterinary diagnosis | BOAS | 64 | 20% |

| Laryngeal Collapse | 31 | 9.7% | |

| Entropion | 34 | 10.6% | |

| Ectropion | 19 | 6.9% | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 72 | 22.5% | |

| Conformation-related surgeries | Ocular surgery | 31 | 9.7% |

| Corrective surgery (cutaneous and respiratory) | 28 | 8.8% | |

| Odontostomatologic surgery | 12 | 3.8% | |

| Sub-Scale | NBDOs | BDOs |

|---|---|---|

| DOI (Dog–Owner Interaction) | 4.08 ± 0.52 | 4.32 ± 0.4 |

| PEC (Perceived Emotional Closeness) | 4.33 ± 0.56 | 4.55 ± 0.44 |

| PC (Perceived Cost) | 3.84 ± 0.44 | 3.68 ± 0.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cannas, S.; Palestrini, C.; Boero, S.; Garegnani, A.; Mazzola, S.M.; Prato-Previde, E.; Berteselli, G.V. Italians Can Resist Everything, Except Flat-Faced Dogs! Animals 2025, 15, 1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101496

Cannas S, Palestrini C, Boero S, Garegnani A, Mazzola SM, Prato-Previde E, Berteselli GV. Italians Can Resist Everything, Except Flat-Faced Dogs! Animals. 2025; 15(10):1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101496

Chicago/Turabian StyleCannas, Simona, Clara Palestrini, Sara Boero, Alice Garegnani, Silvia M. Mazzola, Emanuela Prato-Previde, and Greta V. Berteselli. 2025. "Italians Can Resist Everything, Except Flat-Faced Dogs!" Animals 15, no. 10: 1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101496

APA StyleCannas, S., Palestrini, C., Boero, S., Garegnani, A., Mazzola, S. M., Prato-Previde, E., & Berteselli, G. V. (2025). Italians Can Resist Everything, Except Flat-Faced Dogs! Animals, 15(10), 1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101496