The Complementary Role of Gestures in Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) Communication

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

Review Objectives

- Objective 1: Reveal new insights into gestural communication’s role in spotted hyenas’ social communication, especially in relation to acoustic and olfactory communications.

- Objective 2: Compare captive and wild spotted hyena gestural signal repertoires to show how these signals’ form, frequency, and function vary between these populations.

2. Gestures in Spotted Hyenas

3. How Gestural Communication Complements Acoustic Communication

4. How Gestural Communication Complements Olfactory Communication

5. Social Communication in the Wild vs. Captivity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

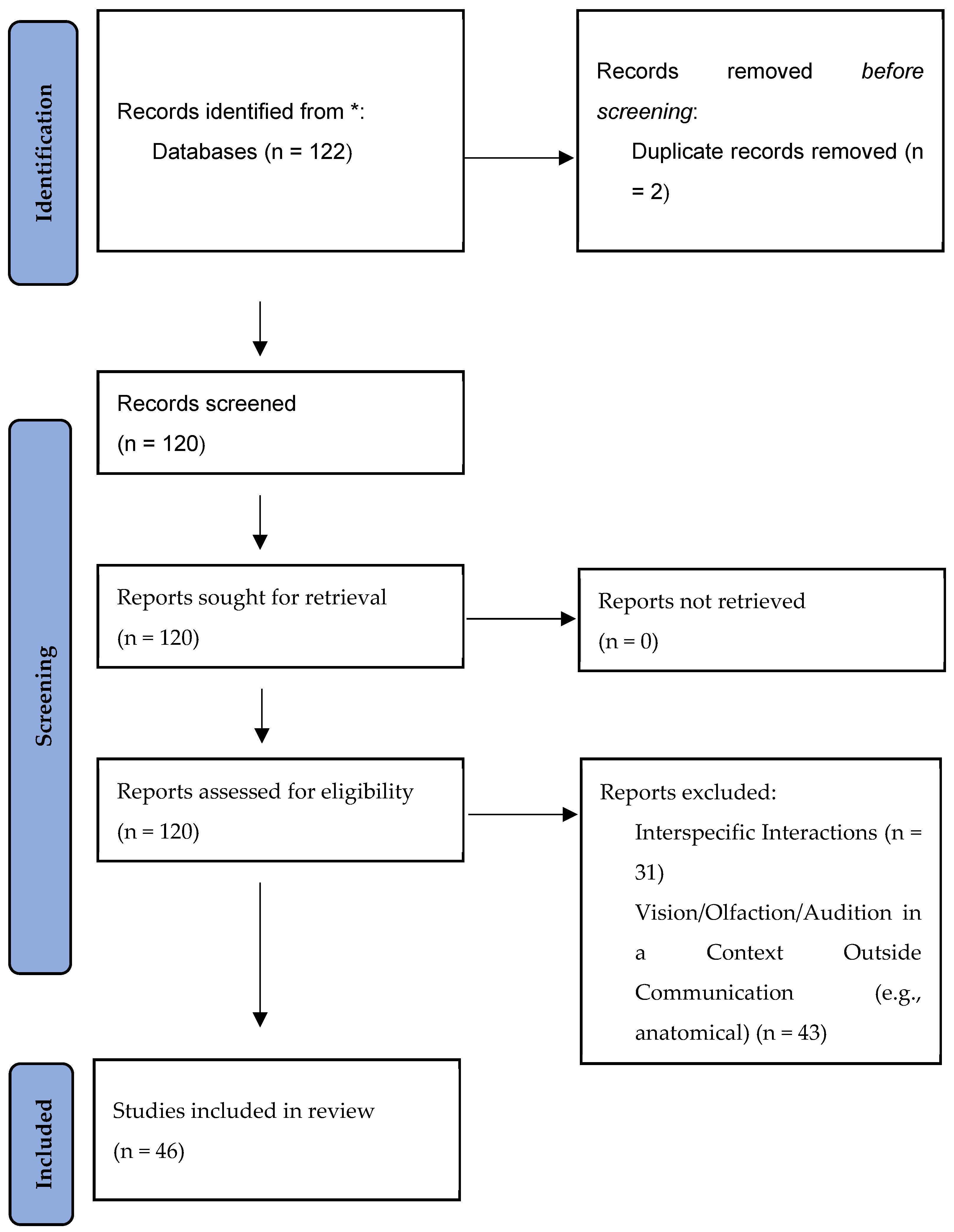

Literature Search

References

- Holekamp, K.E.; Smith, J.E.; Strelioff, C.C.; Van Horn, R.C.; Watts, H.E. Society, demography, and genetic structure in the spotted hyena. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersick, A.S.; Cheney, D.L.; Schneider, J.M.; Seyfarth, R.M.; Holekamp, K.E. Long-distance communication facilitates cooperation among wild spotted hyaenas, Crocuta crocuta. Anim. Behav. 2015, 103, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratford, K.; Stratford, S.; Périquet, S. Dyadic associations reveal clan size and social network structure in the fission–fusion society of spotted hyaenas. Afr. J. Ecol. 2020, 58, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, J.D.; Jordan, N.R.; Gilfillan, G.D.; McNutt, J.W.; Reader, T. Spatial and seasonal patterns of communal latrine use by spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) reflect a seasonal resource defense strategy. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2020, 74, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K.M. Long-Distance Vocal Communication in the Spotted Hyena, Crocuta crocuta; Holekamp, K.E., Ed.; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayssen, V.; Noonan, P. Crocuta crocuta (Carnivora: Hyaenidae). Mamm. Species 2021, 53, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, R.D. Communication about social status. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014, 28, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.E.; Holekamp, K.E. Spotted hyenas; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boydston, E.E.; Morelli, T.L.; Holekamp, K.E. Sex differences in territorial behavior exhibited by the spotted hyena (hyaenidae, Crocuta crocuta). Ethology 2001, 107, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drea, C.M.; Hawk, J.E.; Glickman, S.E. Aggression decreases as play emerges in infant spotted hyaenas: Preparation for joining the clan. Anim. Behav. 1996, 51, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vullioud, C.; Davidian, E.; Wachter, B.; Rousset, F.; Courtiol, A.; Höner, O.P. Social support drives female dominance in the spotted hyaena. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, K.E.; Cooper, S.M.; Katona, C.I.; Berry, N.A.; Frank, L.G.; Smale, L. Patterns of Association among Female Spotted Hyenas (Crocuta crocuta). J. Mammal. 1997, 78, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahaj, S.; Van Horn, R.; Van Horn, T.; Dreyer, R.; Hilgris, R.; Schwarz, J.; Holekamp, K. Kin discrimination in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta): Nepotism among siblings. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2004, 56, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.E.; Memenis, S.K.; Holekamp, K.E. Rank-related partner choice in the fission–fusion society of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007, 61, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, K.E.; Sakai, S.T.; Lundrigan, B.L. Social intelligence in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta). Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 362, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathevon, N.; Koralek, A.; Weldele, M.; Glickman, S.E.; Theunissen, F.E. What the hyena’s laugh tells: Sex, age, dominance, and individual signature in the giggling call of Crocuta crocuta. BMC Ecol. 2010, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis Kevin, R.; Greene Keron, M.; Benson-Amram Sarah, R.; Holekamp, K.E. Sources of Variation in the Long-Distance Vocalizations of Spotted Hyenas. Behaviour 2007, 144, 557–584. [Google Scholar]

- Partan, S.R.; Marler, P. Issues in the classification of multimodal communication signals. Am. Nat. 2005, 166, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, L.N.; Silva, M.L.; Garotti, M.M.; Rodrigues, A.L.; Santos, A.C.; Ribeiro, I.F. Gestural communication in a new world parrot. Behav. Process. 2014, 105, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekoff, M. Social Play and Play-Soliciting by Infant Canids. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2015, 14, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebal, K.; Pika, S.; Tomasello, M. Gestural communication of orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus). Gesture 2006, 6, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, K.E.; Smale, L. Behavioral Development in the Spotted Hyena. Bioscience 1998, 48, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

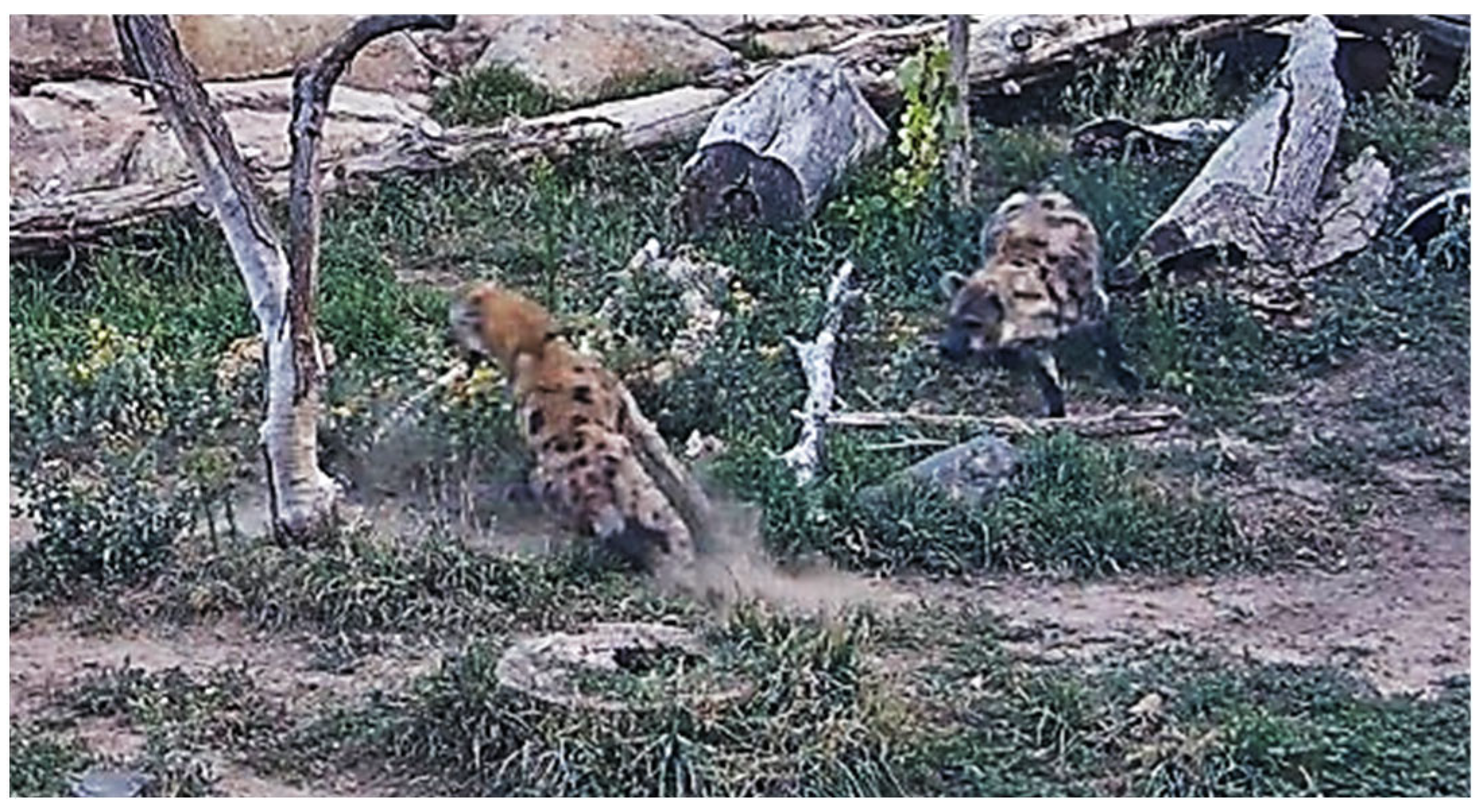

- Nolfo, A.P.; Casetta, G.; Palagi, E. Visual communication in social play of a hierarchical carnivore species: The case of wild spotted hyenas. Curr. Zool. 2022, 68, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.; Rooney, N.; Serpell, J. Dog social behavior and communication. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Casetta, G.; Nolfo, A.P.; Palagi, E. Yawning informs behavioural state changing in wild spotted hyaenas. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2022, 76, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartmill, E.A.; Hobaiter, C. Gesturing towards the future: Cognition, big data, and the future of comparative gesture research. Anim. Cogn. 2019, 22, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolfo, A.P.; Casetta, G.; Palagi, E. Play fighting in wild spotted hyaenas: Like a bridge over the troubled water of a hierarchical society. Anim. Behav. 2021, 180, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molesti, S.; Meguerditchian, A.; Bourjade, M. Gestural communication in olive baboons (Papio anubis): Repertoire and intentionality. Anim. Cogn. 2020, 23, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagi, E.; Norscia, I.; Spada, G. Relaxed open mouth as a playful signal in wild ring-tailed lemurs. Am. J. Primatol. 2014, 76, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llamazares-Martín, C.; Scopa, C.; Guillén-Salazar, F.; Palagi, E. Relaxed Open Mouth reciprocity favours playful contacts in South American sea lions (Otaria flavescens). Behav. Process. 2017, 140, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, M.L.; Hofer, H. Loud calling in a female-dominated mammalian society: II. Behavioural contexts and functions of whooping of spotted hyaenas, Crocuta crocuta. Anim. Behav. 1991, 42, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahaj, S.A.; Guse, K.R.; Holekamp, K.E. Reconciliation in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta). Ethology 2001, 107, 1057–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, G.G.; Ryan, M.J. Visual and acoustic communication in non-human animals: A comparison. J. Biosci. 2000, 25, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, J.W.; Vehrencamp, S.L. Principles of Animal Communication; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1998; Volume 132. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, S.K. Sex and Individual Differences in Agonistic Behavior of Spotted Hyenas (Crocuta crocuta): Effects on Fitness and Dominance; Holekamp, K.E., Ed.; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Penteriani, V.; del Mar Delgado, M.; Alonso-Alvarez, C.; Sergio, F. The importance of visual cues for nocturnal species: Eagle Owls signal by badge brightness. Behav. Ecol. 2007, 18, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drea, C.M.; Vignieri, S.N.; Cunningham, S.B.; Glickman, S.E. Responses to olfactory stimuli in spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta): I. Investigation of environmental odors and the function of rolling. J. Comp. Psychol. 2002, 116, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Leal, I.; Torres, M.V.; Barreiro-Vázquez, J.-D.; López-Beceiro, A.; Fidalgo, L.; Shin, T.; Sanchez-Quinteiro, P. The vomeronasal system of the wolf (Canis lupus signatus): The singularities of a wild canid. J. Anat. 2024, 245, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minasandra, P.; Jensen, F.H.; Gersick, A.S.; Holekamp, K.E.; Strauss, E.D.; Strandburg-Peshkin, A. Accelerometer-based predictions of behaviour elucidate factors affecting the daily activity patterns of spotted hyenas. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern, H.N.; Kruuk, H. The spotted hyena. A study of predation and social behavior. J. Anim. Ecol. 1973, 42, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.E.; Estrada, J.R.; Richards, H.R.; Dawes, S.E.; Mitsos, K.; Holekamp, K.E. Collective movements, leadership, and consensus costs at reunions in spotted hyaenas. Anim. Behav. 2015, 105, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, E.D. Social Inequality and Its Dynamics in Spotted Hyenas; Holekamp, K.E., Ed.; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Benson-Amram, S.; Heinen, V.K.; Gessner, A.; Weldele, M.L.; Holekamp, K.E. Limited social learning of a novel technical problem by spotted hyenas. Behav. Process. 2014, 109 Pt B, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drea, C.M.; Carter, A.N. Cooperative problem solving in a social carnivore. Anim. Behav. 2009, 78, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson-Amram, S.; Weldele, M.L.; Holekamp, K.E. A comparison of innovative problem-solving abilities between wild and captive spotted hyaenas, Crocuta crocuta. Anim. Behav. 2013, 85, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amici, F.; Liebal, K. Testing Hypotheses for the Emergence of Gestural Communication in Great and Small Apes (Pan troglodytes, Pongo abelii, Symphalangus syndactylus). Int. J. Primatol. 2023, 44, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F.E.; Greggor, A.L.; Montgomery, S.H.; Plotnik, J.M. The endangered brain: Actively preserving ex-situ animal behaviour and cognition will benefit in-situ conservation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.L.; Hauser, M.D.; Wrangham, R.W. Does participation in intergroup conflict depend on numerical assessment, range location, or rank for wild chimpanzees? Anim. Behav. 2001, 61, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) Gestural Repertoire | ||

|---|---|---|

| Behavior Name | Gesture Type | Description |

| Head bobbing 4 | Facial | The subject avoids eye contact and lowers the entire cephalic region while pulling the ears back toward the neck. This can then be followed by moving the head back up to a neutral position and repeating the lowering motion, but not always (shows submission). |

| Bite shakes 1 | Manual (Head) | The subject begins to gnash their teeth in the air repeatedly in a chomping motion while simultaneously moving their head back and forth laterally at a vigorous pace (conveying extreme aggression). |

| Ear flattens 1 | Manual (Head) | The subject avoids or intermittently makes eye contact, never directly, and pulls the ears back toward the neck as a submissive signal. |

| Back away 1 | Manual (Body) | The subject moves away from the receiver at a normal walking pace (normal gait or slow lope), but the head is directed perpendicularly to the intended receiver (submissive signal). |

| Grin and retreat 1 | Manual (Body) | The subject quickly performs a facial movement in which the upper lips are widened, and the lower lips appear at an elevated angle. Then, the subject hastily turns the entire body away from the receiver and physically relocates to another spatial area at a fast transverse gallop. No direct contact is observed in any phase (extreme submissive signal). |

| Crawl approach 2 | Manual (Body) | The subject’s hind legs are bent, ears flattened, mouth slightly open, and tail straight up or bent forward as it moves towards the receiver at a slow lope (extreme submissive signal). |

| Affiliative greeting 2 | Manual (Body) | The subject moves towards the receiver. Eye contact is held with the head at a lateral angle if the receiver is socially dominant, or eye contact is held with the head facing forward to a socially subordinate receiver; then, the subject lightly brushes their head against the receiver’s head and/or their genital regions against those of the receiver (in either case, the phallus is erect). |

| Relaxed open mouth 4 | Facial | Subject eye contact is maintained, ears are straight up or slightly tilted towards the sides of the head, and the upper mouth is opened widely. Canines do not protrude beyond normal, giving the sender a pointed snout appearance (initiates play). |

| Spontaneous yawn 5 | Facial | The subject opens its mouth, sometimes protruding its tongue, while simultaneously inhaling deeply until the mouth opening reaches the acme, which exposes the teeth. Mouth closing and air exhalation are more rapid than the mouth opening and inhalation phases. |

| Foot spurring 3 | Manual (Body) | Subject paws ground in a back-and-forth motion with their foot at a slow pace while a receiver is attending to them. Individuals use this as a de-escalatory or anticipatory signal of agonistic behavior. |

| Forward thrust 3 | Manual (Body) | The subject quickly lurches their entire body toward a receiver, then recedes at an equivalent rate. This may be repeated several times in succession, but not constantly (used as an intimidation signal). |

| Gesture | |

|---|---|

| Observed in captive and wild spotted hyenas with identical forms | Head bobbing 4 Relaxed open mouth 4 Spontaneous yawn 5 Bite shakes 1 Ear flattens 1 Back away 1 Grin and retreat 1 |

| Only observed in the wild | Crawl approach 2 |

| Gestures with differing forms | Affiliative greeting 2 Foot spurring 3 Forward thrust 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laurita, A.J.; Poindexter, S.A. The Complementary Role of Gestures in Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) Communication. Animals 2025, 15, 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101366

Laurita AJ, Poindexter SA. The Complementary Role of Gestures in Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) Communication. Animals. 2025; 15(10):1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101366

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaurita, Andrew J., and Stephanie A. Poindexter. 2025. "The Complementary Role of Gestures in Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) Communication" Animals 15, no. 10: 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101366

APA StyleLaurita, A. J., & Poindexter, S. A. (2025). The Complementary Role of Gestures in Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) Communication. Animals, 15(10), 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101366