Investigation of PRRS Virus Infection in Hungarian Wild Boar Populations during Its Eradication from Domestic Pig Herds

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Laboratory Processing

2.3. Data Processing

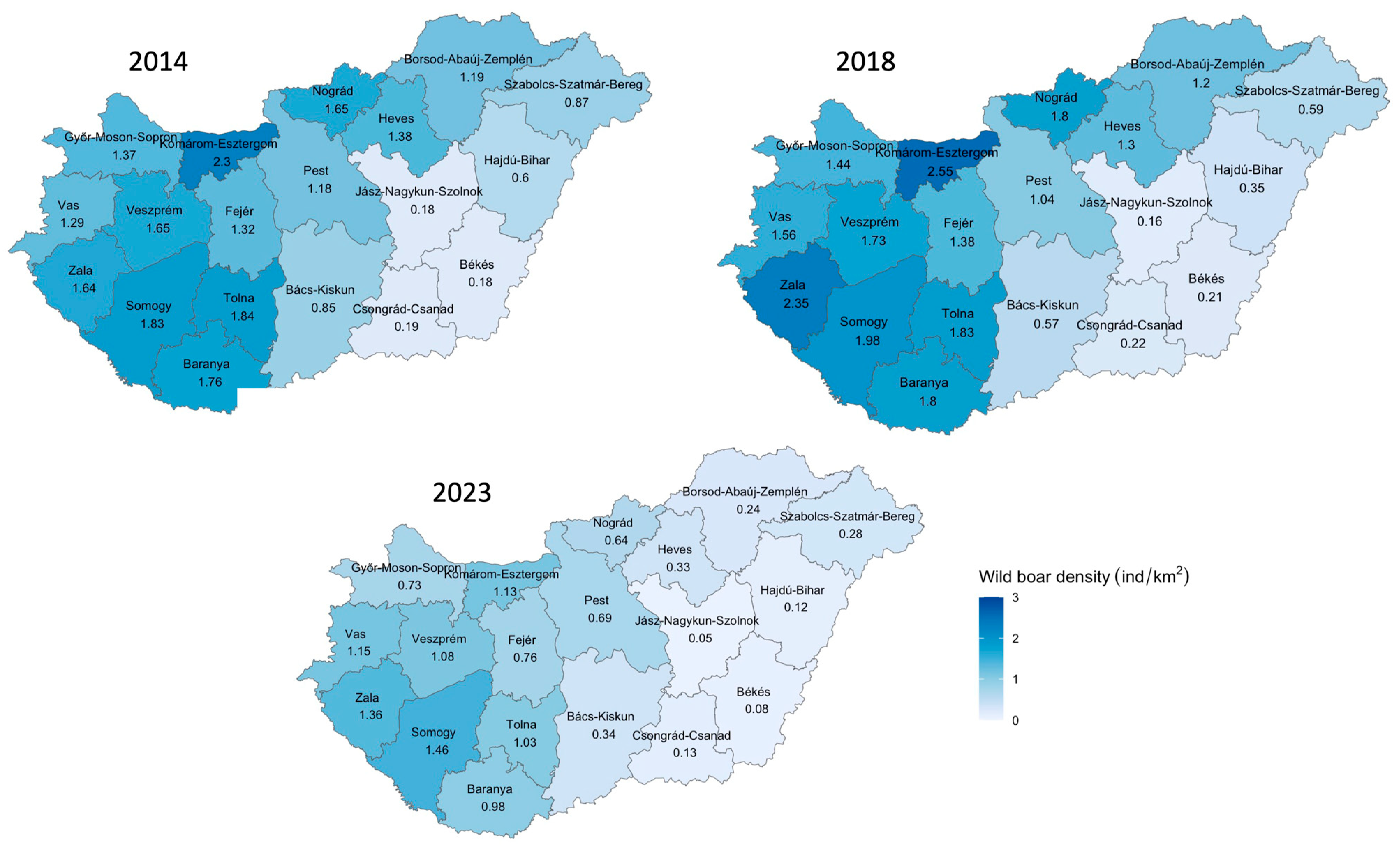

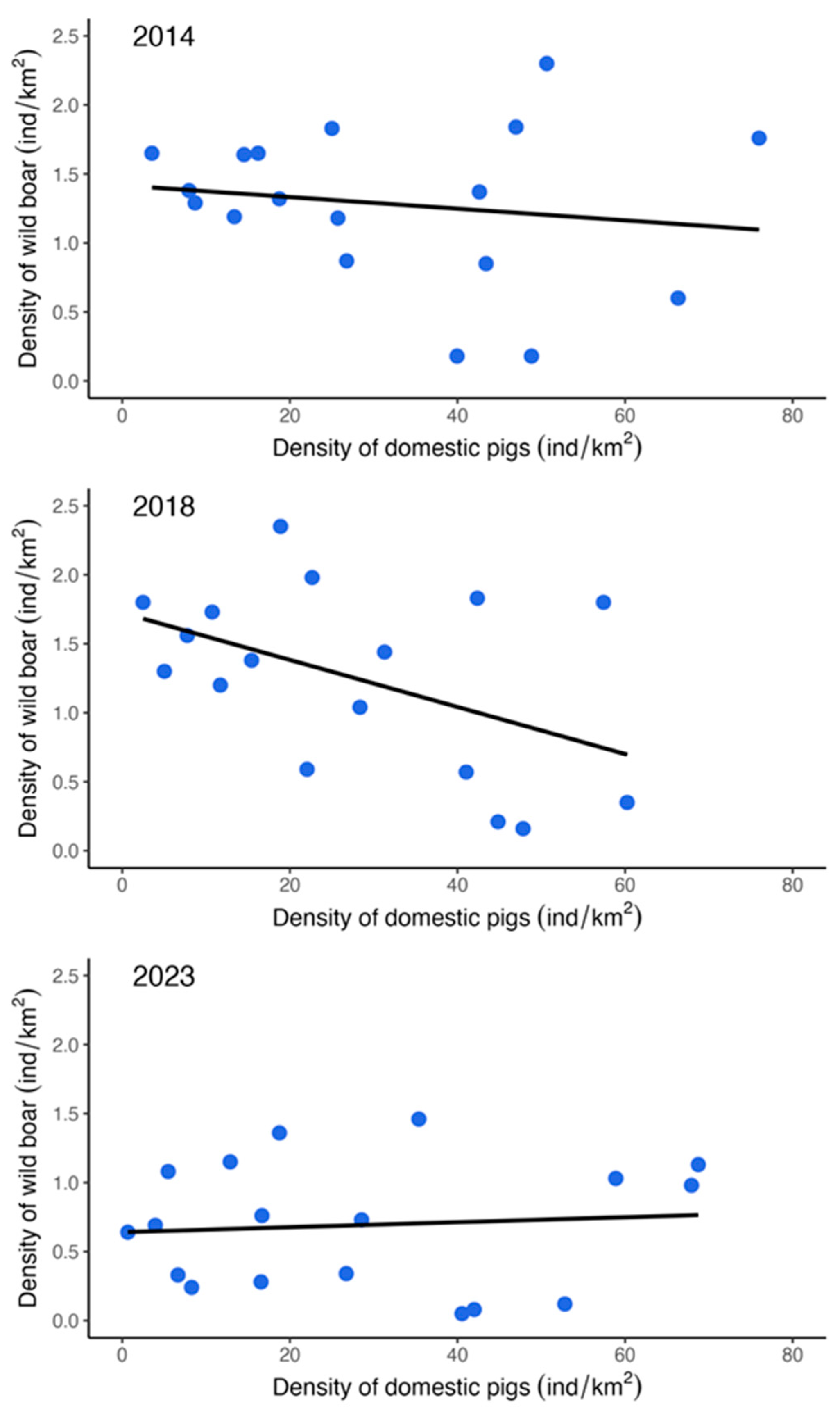

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lunney, J.K.; Benfield, D.A.; Rowland, R.R. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: An update on an emerging and re-emerging viral disease of swine. Virus Res. 2010, 154, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes-Donoso, P.; Alvarez, J.; Jarvis, L.S.; Morrison, R.B.; Perez, A.M. Production Losses from an Endemic Animal Disease: Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) in Selected Midwest US Sow Farms. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtkamp, D.J.; Polson, D.D.; Torremorell, M.; Morrison, B.; Classen, D.M.; Becton, L.; Henry, S.; Rodibaugh, M.T.; Rowland, R.R.; Snelson, H.; et al. Terminology for classifying swine herds by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus status. J. Swine Health Prod. 2011, 19, 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish PRRS Elimination Project 2019 Innovative Farmers. Available online: https://innovativefarmers.org/field-lab?id=f0ea179b-5ddc-e811-816f-05056ad0bd4 (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Jim Long Pork Commentary—Nov 26, 2018. Available online: https://genesus.com/jim-long-pork-commentary-nov-26-2018/ (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Renken, C.; Nathues, C.; Swam, H.; Fiebig, K.; Weiss, C.; Eddicks, M.; Ritzmann, M.; Nathues, H. Application of an economic calculator to determine the cost of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome at farm-level in 21 pig herds in Germany. 2021. Porc. Health Manag. 2021, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, I.; Nemes, I.; Búza, L.; Polyák, F.; Bálint, Á.; Fitos, G.; Holtkamp, D.J.; Ózsvári, L. The Impact of PRRS Eradication Program on the Production Parameters of the Hungarian Swine Sector. Animals 2023, 13, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirtle, E.C.; Beran, G.W. Stability of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in the presence of fomites commonly found on farms. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1996, 208, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, S.A.; Martinez, B.C.; Clanton, C. Survival and infectivity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in swine lagoon effluent. Vet. Rec. 2005, 156, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlinger, V.F.; Pesch, S.; Bischoff, C. History, occurrence, dynamics and current status of PRRS in Europe. Vet. Res. 2000, 31, 86–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRRS Prevalence in Europe: Perception of the Pig Veterinary Practitioners. Available online: https://www.prrs.com/expertise/publications/esphm-2015/prrs-prevalence-europe-perception-pig-veterinary-practitioners (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Reiner, G.; Fresen, C.; Bronnert, S.; Willems, H. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) infection in wild boars. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 136, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albina, E.; Mesplède, A.; Chenut, G.; Le Potier, M.F.; Bourbao, G.; Le Gal, S.; Leforban, Y. A serological survey on classical wine fever (CSF), Aujeszky’s disease (AD) and Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) virus infections in French wild boars from 1991 to 1998. Vet. Microbiol. 2000, 77, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliki, J.T.; Rodgers, S.J.; Eskew, G. Serosurvey of selected viral and bacterial diseases in wild swine from Oklahoma. J. Wildl. Dis. 1998, 34, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, K.; Miller, R.S.; Musante, A.R.; White, T.S.; Freye II, J.D.; Gidlewski, T. Antibody evidence of porcine reproductive and respiratory disease virus detected in sera collected from feral swine (Sus scrofa) across the United States. J. Swine Health Prod. 2018, 26, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankevicius, A.; Buitkuviene, J.; Sutkiene, V.; Spancerniene, U.; Pampariene, I.; Pautienius, A.; Oberauskas, V.; Zilinskas, H.; Zymantiene, J. Detection and molecular characterization of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in Lithuanian wild boar populations. Acta Vet. Scand. 2015, 58, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, V.; Kukielka, D.; Martínez-López, B.; de las Heras, A.I.; Barasona, J.Á.; Gortázar, C.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M.; Vicente, J. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) virus in wild boar and Iberian pigs in south-central Spain. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2013, 59, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilcek, S.; Molnar, L.; Vlasakova, M.; Jackova, A. The first detection of PRRSV in wild boars in Slovakia. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2015, 128, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Cong, X.; Chi, X.; Li, J.; et al. Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome in Hybrid Wild Boars, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1071–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J.; Lee, C.H.; Hyun, B.H.; Kim, J.J.; Lim, S.I.; Song, J.Y.; Shin, Y.K. A survey of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome among wild boar populations in Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2012, 13, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, Y.; Saito, T.; Tanaka, E.; Takashima, Y. A serological survey of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in wild boar in Gifu Prefecture, Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 84, 1406–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Dahouk, S.; Nöckler, K.; Tomaso, H.; Splettstoesser, W.D.; Jungersen, G.; Riber, U.; Petry, T.; Homann, D.; Scholz, H.C.; Hensel, A.; et al. Seroprevalence of brucellosis, tularemia, and yersiniosis in wild boars (Sus scrofa) from North-Eastern Germany. J. Vet. Med. B 2005, 52, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, I.; Nemes, I.; Bognár, L.; Terjék, Z.; †Molnár, T.; Abonyi, T.; Bálint, Á.; Horváth, D.G.; Balka, G. Eradication of PRRS from Hungarian pig herds between 2014 and 2022. Animals 2023, 13, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, I.; Molnár, T. Eradication of Aujeszky’s disease in Hungary between 1998 and 2002. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2004, 126, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- National action plan on the regulation of the wild boar population in connection with the prevention, control and eradication of African swine fever. Az Országos Fõállatorvos 2/2021. számú határozata. Földművelésügyi Értesítő (Agric. Bull.) 2021, 71, 259–333. (In Hungarian)

- Csányi, S.; Márton, M.; Bőti, S.; Schally, G. Wildlife Management Data Base—2022/2023 Hunting Year. MATE VTI; National Wildlife Data Repository: Gödöllő, Hungary, 2023; 70p. [Google Scholar]

- Hungarian Central Statistical Office, A Mezőgazdaság Főbb Adatai (1960–)(3/3). Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xstadat/xstadat_hosszu/h_omf001c.html (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (Infection with Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus). In WOAH Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals; 2021; Chapter 3.9.6; Available online: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.09.06_PRRS.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Detection of PRRS Virus Virotype PRRSV Real-Time PCR Method, Virotype PRRSV RT-PCR Kit Handbook for Detection of RNA from Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. 2014. Available online: https://www.qiagen.com/de/resources/resourcedetail?id=82ff9d2a-db7d-44ad-976c-c459a456c398&lang=en (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Komsta, L.; Novomestky, F. Moments: Moments, Cumulants, Skewness, Kurtosis and Related Rests. R Package Version 0.14.1. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=moments (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- ENETWILD-Consortium; Sebastián-Pardo, M.; Laguna, E.; Csányi, S.; Gacic, D.; Katona, K.; Mirceta, J.; Benedek, Z.; Beltrán-Alcrudo, D.; Terjék, Z.; et al. Assessment of the factors for the presence of wild boar near outdoor and extensive pig farms in two areas of Eastern Europe. EFSA Extern. Sci. Rep. 2023, 20, 8015E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, K.; Podgórska, K.; Tyszka, A.; Stadejek, T. Comparison of six commercial ELISAs for the detection of antibodies against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in field serum samples. Res. Vet. Sci. 2018, 121, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| County | PRRS ELISA | PRRS PCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Positive | Total | Positive | |

| Bács-Kiskun | 383 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Baranya | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Békés | 287 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Csongrád | 450 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Fejér | 10 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Győr-Moson-Sopron | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hajdú-Bihar | 234 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Heves | 18 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok | 532 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Komárom-Esztergom | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nógrád | 92 | 0 | 95 | 0 |

| Pest | 310 | 0 | 123 | 0 |

| Somogy | 16 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg | 159 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| Tolna | 218 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Vas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Veszprém | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Zala | 74 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2842 | 12 | 274 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bálint, Á.; Csányi, S.; Nemes, I.; Bijl, H.; Szabó, I. Investigation of PRRS Virus Infection in Hungarian Wild Boar Populations during Its Eradication from Domestic Pig Herds. Animals 2024, 14, 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14111537

Bálint Á, Csányi S, Nemes I, Bijl H, Szabó I. Investigation of PRRS Virus Infection in Hungarian Wild Boar Populations during Its Eradication from Domestic Pig Herds. Animals. 2024; 14(11):1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14111537

Chicago/Turabian StyleBálint, Ádám, Sándor Csányi, Imre Nemes, Hanna Bijl, and István Szabó. 2024. "Investigation of PRRS Virus Infection in Hungarian Wild Boar Populations during Its Eradication from Domestic Pig Herds" Animals 14, no. 11: 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14111537

APA StyleBálint, Á., Csányi, S., Nemes, I., Bijl, H., & Szabó, I. (2024). Investigation of PRRS Virus Infection in Hungarian Wild Boar Populations during Its Eradication from Domestic Pig Herds. Animals, 14(11), 1537. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14111537