Comparison of 12 Different Animal Welfare Labeling Schemes in the Pig Sector

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pig Welfare Labels Studied

2.2. Animal Welfare Implications of Measures Covered by the Labels

2.2.1. Free Farrowing

2.2.2. Space Allowance

2.2.3. Outdoor Access

2.2.4. Enrichments

2.2.5. Bedding

2.2.6. Painful Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Inspection of the Schemes

3.2. Measures to Promote the Welfare of Pigs in the Schemes

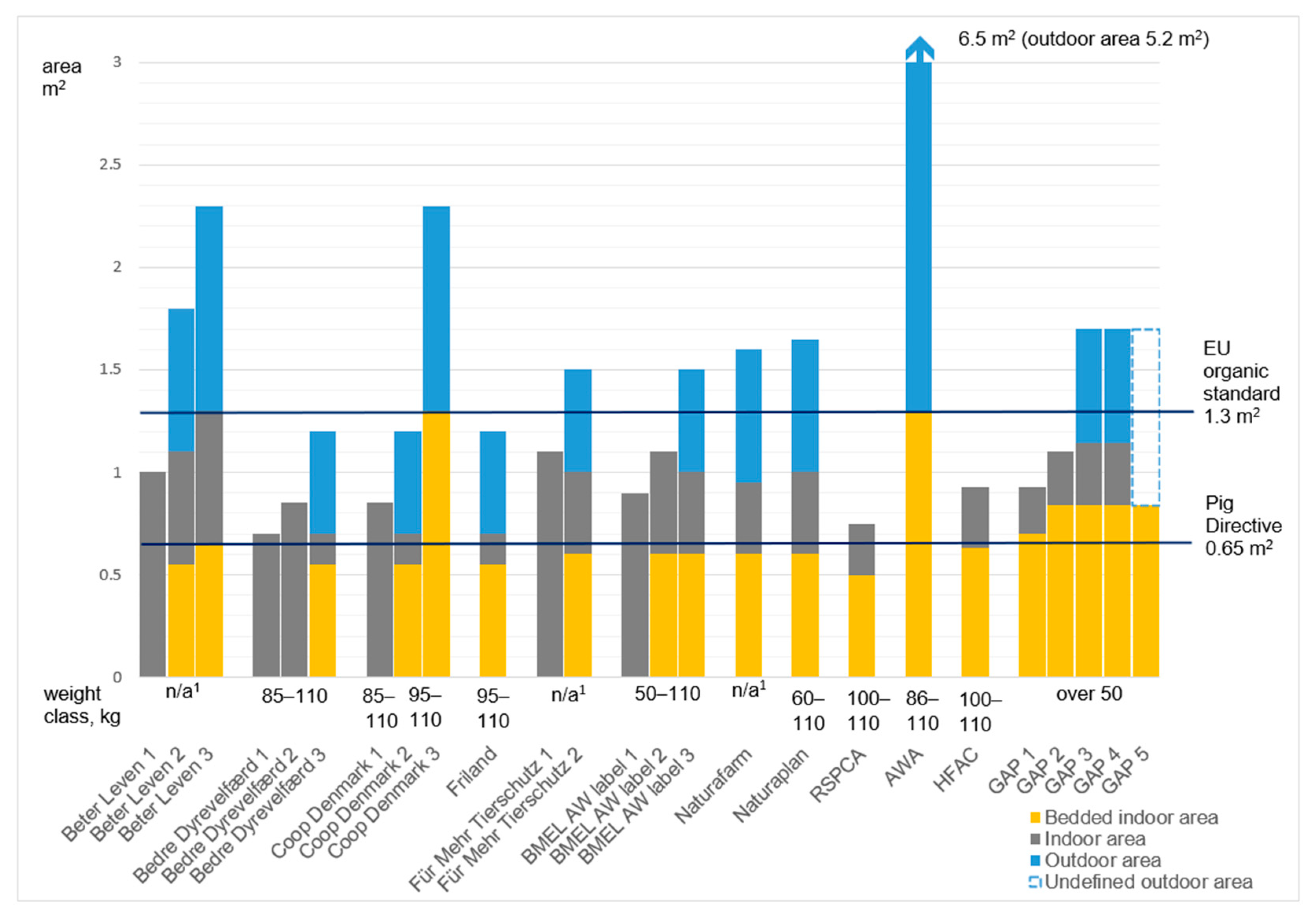

3.2.1. The Space Requirements and Outdoor Access for Fattening Pigs

3.2.2. Floor Type, Bedding, and Enrichments

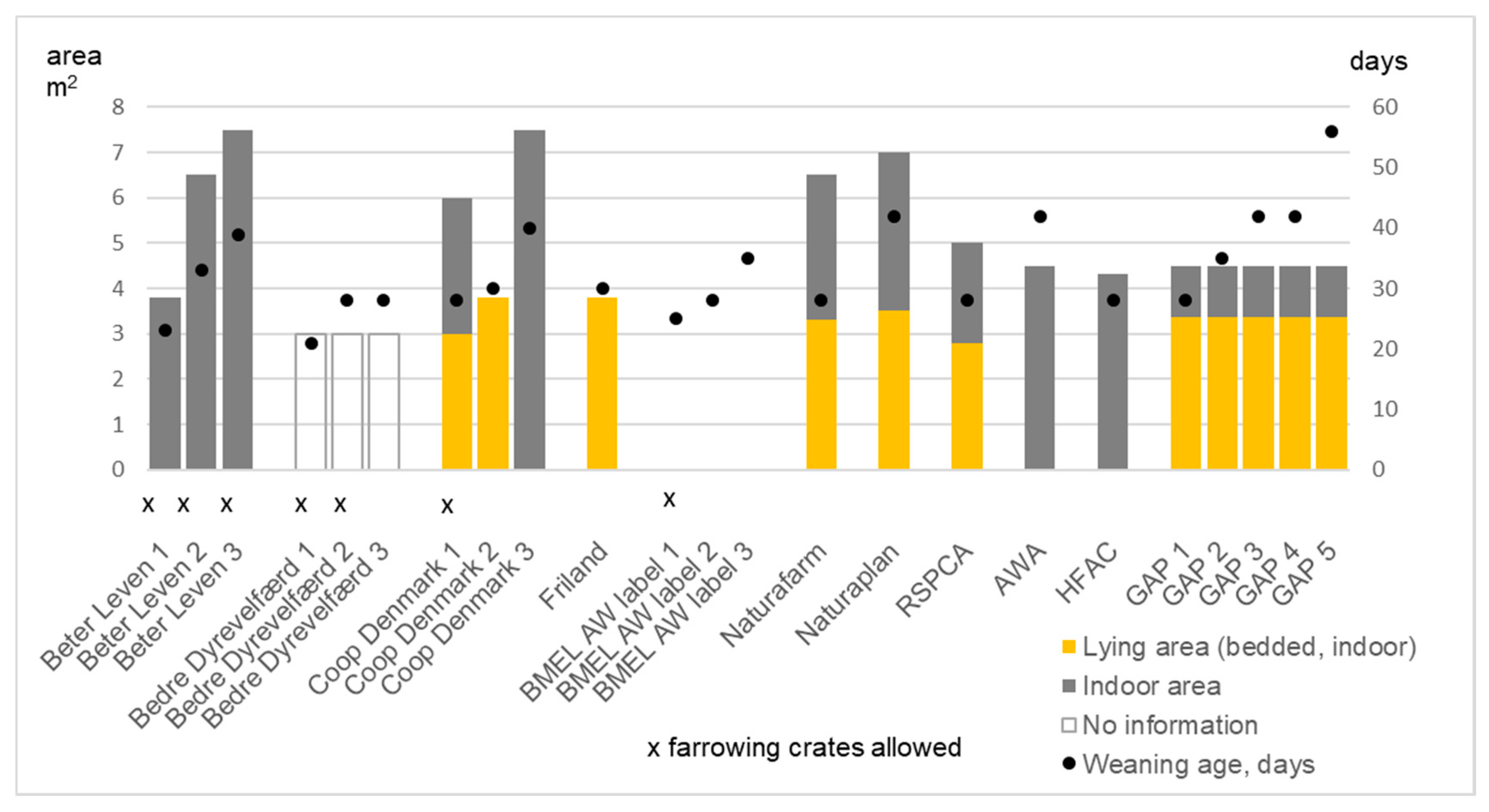

3.2.3. Farrowing-Related Criteria

3.2.4. Transport Time

3.2.5. Mutilations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ohl, F.; van der Staay, F.J. Animal welfare: At the interface between science and society. Vet. J. 2012, 192, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. Council Directive 2008/120/EC of 18 December 2008 laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, L47, 5–13. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32008L0120 (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- TNS Opinion & Social. Special Eurobarometer 442. Attitudes of Europeans toward Animal Welfare. 2015. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/88u/dataset/S2096_84_4_442_ENG (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- Clark, B.; Panzone, L.A.; Stewart, G.B.; Kyriazakis, I.; Niemi, J.K.; Latvala, T.; Tranter, R.; Jones, P.; Frewer, L.J. Consumer attitudes toward production diseases in intensive production systems. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DVFA. Sammen om Bedre Dyrevelfærd. Available online: https://www.foedevarestyrelsen.dk/kampagner/Bedre-dyrevelfaerd/Sider/Hvem_st%C3%A5r_bag_m%C3%A6rket.aspx (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Animal Welfare—An Integral Part of Sustainable Animal Production. 14975/19. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/41863/st14975-en19.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Animal Welfare—Label. 13691/20. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-13691-2020-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on organic production and labeling of organic products and repealing. Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, L150, 1–93. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018R0848 (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Niemi, J.K.; Bennet, R.; Clark, B.; Frewer, L.; Jones, P.; Rimmler, T.; Tranter, R. A value chain analysis of interventions to control production diseases in the intensive pig production sector. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Loo, E.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ valuation of sustainability labels on meat. Food Pol. 2014, 49, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Pol. 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heerwagen, L.R.; Mørkbak, M.R.; Denver, S.; Sandøe, P.; Christensen, T. The role of quality labels in market-driven animal welfare. J. Agr. Environ. Ethic. 2015, 28, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. Labels for Animal Husbandry Systems Meet Consumer Preferences: Results from a Meta-analysis of Consumer Studies. J. Agr. Environ. Ethic. 2016, 29, 1071–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Stewart, G.B.; Panzone, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Frewer, L.J. A Systematic Review of Public Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviours Toward Production Diseases Associated with Farm Animal Welfare. J. Agr. Environ. Ethic. 2016, 29, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sörensen, J.; Schrader, L. Labeling as a Tool for Improving Animal Welfare—The Pig Case. Agriculture 2019, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eurogroup for animals. Method of Production Labeling: The Way forward to Sustainable Trade. Policy Brief. Available online: https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/sites/eurogroup/files/2020-02/E4A-Policy-Paper-Labeling_and_WTO_04-2019-screen_0.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Beter Leven. Varkens. Available online: https://beterleven.dierenbescherming.nl/zakelijk/deelnemen/bedrijfstypen/veehouderijen/varkens/ (accessed on 29 August 2018).

- Friland. Code of Practice. Available online: https://www.friland.com/media/2154/friland-free-range-code-of-practice-december-2019-final.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Coop Denmark. Dyrevelfærd så det Kan Mærkes. Available online: http://xn--dyrevelfrd-k6a.coop.dk/dyrevelfaerdshjertet/ (accessed on 9 January 2020).

- Bedre Dyrevelfærd. Bekendtgørelse om Frivillig Dyrevelfærdsmærkningsordning. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2019/1441 (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- BMEL. Das Staatliche Tierwohlkennzeichen. Available online: https://www.tierwohl-staerken.de/einkaufshilfen/tierwohlkennzeichen (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Für Mehr Tierschutz. Tierschutzlabel. Available online: https://www.tierschutzlabel.info/tierschutzlabel/ (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- RSPCA Welfare Standards for Pigs. 2020. Available online: https://science.rspca.org.uk/sciencegroup/farmanimals/standards/pigs (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Naturafarm. Richtlinie Coop Naturafarm Porc. Available online: https://www.coop.ch/content/dam/naturafarm/standards/rl_cnf_porc_d.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Naturaplan. Standards for the Production, Processing and Trade of “Bud” Products. Available online: https://www.biosuisse.ch/media/VundH/Regelwerk/2020/EN/bio_suisse_richtlinien_2020_-_en.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- AWA. Pig Standards. Available online: https://agreenerworld.org/certifications/animal-welfare-approved/standards/pig-standards/ (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- HFAC. Pigs. Available online: https://certifiedhumane.org/wp-content/uploads/Std19.Pigs_.2H-1.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- GAP. 5-Step® Animal Welfare Rating Standards for Pigs v2.3. Available online: https://globalanimalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/5-Step-Animal-Welfare-Rating-Standards-for-Pigs-v2.3-20180712.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Council of the European Union. Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2005 on the Protection of Animals during Transport and Related Operations and Amending Directives 64/432/EEC and 93/119/EC and Regulation (EC) No 1255/97. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FI/TXT/?qid=1460634786548&uri=CELEX:32005R0001 (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Loftus, L.; Bell, G.; Padmore, E.; Atkinson, S.; Henworth, A.; Hoyle, M. The effect of two different farrowing systems on sow behaviour, and piglet behaviour, mortality and growth. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 232, 105102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, C.; Heinonen, M.; Valros, A.; Hälli, O.; Peltoniemi, O.A.T. Effect of the environment on the physiology of the sow during late pregnancy, farrowing and early lactation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 105, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, S.P.; Ewen, M.; Rooke, J.A.; Edwards, S.A. The effect of space allowance on performance, aggression and immune competence of growing pigs housed on straw deep litter at different group sizes. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2000, 66, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, H.M.; Dirx-Kuijken, N.C.P.M.M.; Bracke, M.B.M. Exploration Feeding and Higher Space Allocation Improve Welfare of Growing-Finishing Pigs. Animals 2017, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Munsterhjelm, C.; Heinonen, M.; Valros, A. Application of the Welfare Quality® animal welfare assessment system in Finnish pig production, part II: Associations between animal-based and environmental measures of welfare. Anim. Welf. 2015, 24, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weng, R.; Edwards, S. Behaviour, social interactions and lesion scores of group-housed sows in relation to floor space allowance. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 59, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remience, V.; Wavreille, J.; Canart, B.; Meunier-Salaun, M.; Prunier, A.; Bartiaux-Thrill, N.; Nicks, B.; Vandenheede, M. Effects of dry space allowance on the welfare of dry sows kept in dynamic groups and fed with an electronic sow feeder. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 112, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, T.; Takahashi, A.; Imai, S.; Okitsu, A.; Komiyama, S.; Irimajiri, M.; Matsuura, A.; Yamazaki, A.; Hodate, K. Effects of Outdoor Housing of Piglets on Behavior, Stress Reaction and Meat Characteristics. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etterlin, P.E.; Ytrehus, B.; Lundeheim, N.; Heldmer, E.; Österberg, J.; Ekman, S. Effects of free-range and confined housing on joint health in a herd of fattening pigs. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krieter, J.; Schinder, R.; Tölle, K.-H. Health conditions of growing-finishing pigs in fully-slatted pens and multi-surface systems. Dtsch. Tierärztliche Wochenschr. 2004, 111, 462–466. [Google Scholar]

- Studnitz, M.; Jensen, M.B.; Pedersen, L.J. Why do pigs root and what will they root? A review on the exploratory behavior of pigs in relation to environmental enrichment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 107, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alban, L.; Petersen, J.V.; Busch, M.E. A comparison between lesions found during meat inspection of finishing pigs raised under organic/free-range conditions and conventional, indoor conditions. Porc. Health Manag. 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beattie, V.E.; O’Connell, N.E.; Moss, B.W. Influence of environmental enrichment on the behaviour, performance and meat quality of domestic pigs. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2000, 65, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, S.H.; Clutton, E.; Di Giminiani, P.; Rutherford, K.M.D. A Review of Pain Assessment in Pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 28, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 889/2008 of 5 September 2008 Laying down Detailed Rules for the Implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 on Organic Production and Labeling of Organic Products with Regard to Organic Production, Labeling and Control. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L:2008:250:FULL&from=EN (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document Executive Summary of the Evaluation of the European Union Strategy for the Protection and Welfare of Animals 2012–2015. Brussels, 31 March 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/animals/docs/aw_eu_strategy_exec_summ_04042021_en.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Broom, D.M.; Animal Welfare in the European Union. European Parliament Policy Department, Citizen’s Rights and Constitutional Affairs, Study for the PETI Committee. Brussels. 2017. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/74df7b49-ffe7-11e6-8a35-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Weber, R.; Keil, N.M.; Fehr, M.; Horat, R. Piglet mortality on farms using farrowing systems with or without crates. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R.; Keil, N.M.; Fehr, M.; Horat, R. Factors affecting piglet mortality in loose farrowing systems on commercial farms. Livest. Sci. 2009, 124, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbride, A.L.; Mendl, M.; Statham, P.; Held, S.; Harris, M.; Cooper, S.; Green, L.E. A cohort study of preweaning piglet mortality and farrowing accommodation on 112 commercial pig farms in England. Prev. Vet. Med. 2012, 104, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.J.; Jorgensen, G.; Berg, P.; Andersen, I.L. Neo-natal piglet traits of importance for survival in crates and indoor pens. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevi, A. Animal-based measures for welfare assessment. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemelsfelder, F. Qualitative Behaviour Assessment (QBA): A novel method for assessing animal experience. Proc. Brit. Soc. Anim. Sci. 2008, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis, J.E.; Schouten, W.G.P.; Schrama, J.W.; Wiegant, V.M. Effects of rearing and housing environment on pigs with different coping characteristics. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 101, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; Loureiro, M.L.; Nayga, R.M. Valuing an EU Animal Welfare Label using Experimental Auctions. Agr. Econ. 2011, 42, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Stewart, G.B.; Panzone, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Frewer, L.J. Citizens, consumers and farm animal welfare: A meta-analysis of willingness-to-pay studies. Food Pol. 2017, 68, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Name | Number of Tiers | Country of Origin | Established | Inspection Frequency and Certification Body |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beter Leven | 3 | the Netherlands | 2007 | Annually, by external Beter Leven label foundation |

| Bedre Dyrevelfærd | 3 | Denmark | 2017 | Annually, by an accredited certification body |

| Coop Denmark | 4 | Denmark | 2016 | Annually, accredited by Baltic Control Ltd. according to EN 17065 |

| Friland free range | 1 | Denmark | 1992 | Annually, by The Danish Animal Welfare Society inspector |

| Staatliches Tierwohlkennzeichen | 3 | Germany | to come | Twice each year, by an external body |

| Für Mehr Tierschutz | 2 | Germany | 2009 | At least two unannounced audits each year, risk-based control, and certification scheme, by an accredited certification body |

| Naturafarm Coop | 1 | Switzerland | 2007 | Regular unannounced inspections, by Swiss Animal Protection |

| Naturaplan Coop | 1 | Switzerland | 1993 | Annually, by an independent, state-accredited institutions |

| Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) Assured | 1 | Great Britain | 2015 | Annually, by RSPCA Assured scheme assessors. In addition, at least 30% of farms receive a monitoring visit by an RSPCA farm livestock officer, often unannounced |

| Animal Welfare Approved | 1 | USA | 2006 1 | Annually, by A Greener World’s independent trained auditors |

| Certified Humane | 1 | USA | 1998 | Annually, by inspectors who must have an MSc or PhD in animal science or a veterinary degree |

| Global Animal Partnership | 5(+) 2 | USA | 2008 | Certificate maintained for 15 months, by independent third party certifiers |

| Label and Tier Number | Enrichments | Bedding | Solid or Slatted Floor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation on the protection of pigs 2008/120/EC | Permanent access to a sufficient quantity of material to enable proper investigation and manipulation activities, such as straw, hay, wood, sawdust, mushroom compost, peat, or a mixture of such | Bedding not requiredLying area must be comfortable, clean, and dry | Slatted floors allowed |

| EU organic regulation 2007/834/EC | Exercise areas shall permit dunging and rooting by porcine animals For the purposes of rooting, different substrates may be used | Bedding required, straw or other suitable natural material | A comfortable, clean, and dry laying or rest area of sufficient size, consisting of a solid construction which is not slatted |

| Beter Leven 1 | e.g., edible material such as alfalfa in combination with a block of wood and/or a sturdy piece of rope 1,2 | The solid floor part may consist of a rubber mat with litter on it | 40% of the total area solid floor |

| Beter Leven 2 | Ground cover such as straw or hay is extremely suitable | Straw or comparable material entire floor covered | 50% of the total area solid |

| Beter Leven 3 | Ground cover such as straw or hay is extremely suitable | Straw or comparable material entire floor covered | 50% of the total area solid |

| BedreDyrevelfærd 1 | Straw | Rooting material | Not applicable |

| Bedre Dyrevelfærd 2 | Straw | Rooting material | Not applicable |

| Bedre Dyrevelfærd 3 | Straw | Straw | Not applicable |

| Coop DK 1 | Straw or roughage | Straw or roughage | Farrowing sows: 50% solid area |

| Coop DK 2 | Straw, rough feed, roughage | Straw or wood shaving | |

| Coop DK 3 | Straw | Straw | 50% of the total area solid |

| Friland | No information available | Straw, flakes, or similar material | Slatted floor not allowed at the lying areas. Only 50% of non-bedded area may be slatted. |

| Für Mehr Tierschutz 1 | Organic material | No requirements 3 | 0% (no requirement for solid area) |

| Für Mehr Tierschutz 2 | Organic material | Straw or some other bedding material | Lying area must be solid |

| BMEL FAW label 1 | Materials such as straw, hay, sawdust, mushroom compost, or peat | Not applicable | Lying area must be solid |

| BMEL FAW label 2 | Materials such as straw, hay, sawdust, mushroom compost, or peat | The lying area must be bedded, no requirements for bedding material | Lying area must be solid |

| BMEL FAW label 3 | Materials such as straw, hay, sawdust, mushroom compost, or peat | The lying area must be bedded, no requirements for bedding material See the organic label requirements | Lying area must be solid |

| Naturafarm Coop | Straw, different surfaces | Bottom-covered, dry-lying area without perforation | 50% of total area solid |

| Naturaplan Coop | Straw, different surfaces | All lying areas must have bedding | Lying area must be solid |

| RSPCA Assured | High quality straw, peat, and silages | Bedded to a sufficient extent to avoid discomfort, solid construction | Lying area must be solid |

| AWA | Where vegetative cover cannot be maintained throughout the year manipulable material must be provided | Recommended bedding with straw or corn stover is preferred | 100% solid floor |

| HFAC | e.g., wood chips, sawdust, or peat Also objects for manipulation, such as chains, balls and materials such rope | Bedded to a sufficient extent to avoid discomfort | Lying area must be solid |

| GAP 1 | No requirements | e.g., sawdust, wood shavings, wood chips, rice hulls, long or chopped straw, alfalfa pellets, and corn stalks | 75% of the total area solid |

| GAP 2 | e.g., long straw, hay, silage, wood chips, branches, whole crop peas or barley, compost, peat, sisal ropes, or other natural material | e.g., sawdust, wood shavings, wood chips, rice hulls, long or chopped straw, alfalfa pellets, and corn stalks | 75% of the total area solid |

| GAP 3 | e.g., long straw, hay, silage, wood chips, branches, whole crop peas or barley, compost, peat, sisal ropes, or other natural material | e.g., sawdust, wood shavings, wood chips, rice hulls, long or chopped straw, alfalfa pellets, and corn stalks | 75% of the total area solid |

| GAP 4 | e.g., long straw, hay, silage, wood chips, branches, whole crop peas or barley, compost, peat, sisal ropes, or other natural material | e.g., sawdust, wood shavings, wood chips, rice hulls, long or chopped straw, alfalfa pellets, and corn stalks | 75% of the total area solid |

| GAP 5 | Pasture access at all times |

| Label and Tier | Castration Policy |

|---|---|

| Beter Leven 1 | Not allowed |

| Beter Leven 2–3 | Allowed surgically with anesthesia, pain medication required afterwards |

| Bedre Dyrevelfærd 1–3 | Not applicable |

| Coop Denmark 1–3 | Not applicable |

| Friland | Allowed surgically with anesthesia, pain medication required |

| Für Mehr Tierschutz 1–2 | Allowed surgically under general anesthesia (isoflurane), pain medication required, immunological castration allowed |

| BMEL AW label 1–3 | Allowed surgically with anesthesia |

| Naturafarm Coop | Allowed surgically with anesthesia |

| Naturaplan Coop | Allowed surgically with anesthesia |

| RSPCA Assured | Only immunological castration allowed |

| AWA | Allowed surgically for up to 7-day-old pigs, immunological castration prohibited |

| HFAC | Allowed surgically for up to 7-day-old pigs |

| GAP 1–4 | Allowed surgically for up to 10-day-old pigs |

| GAP 5 | Not allowed |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heinola, K.; Kauppinen, T.; Niemi, J.K.; Wallenius, E.; Raussi, S. Comparison of 12 Different Animal Welfare Labeling Schemes in the Pig Sector. Animals 2021, 11, 2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082430

Heinola K, Kauppinen T, Niemi JK, Wallenius E, Raussi S. Comparison of 12 Different Animal Welfare Labeling Schemes in the Pig Sector. Animals. 2021; 11(8):2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082430

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeinola, Katriina, Tiina Kauppinen, Jarkko K. Niemi, Essi Wallenius, and Satu Raussi. 2021. "Comparison of 12 Different Animal Welfare Labeling Schemes in the Pig Sector" Animals 11, no. 8: 2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082430

APA StyleHeinola, K., Kauppinen, T., Niemi, J. K., Wallenius, E., & Raussi, S. (2021). Comparison of 12 Different Animal Welfare Labeling Schemes in the Pig Sector. Animals, 11(8), 2430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082430