Laser Light Pointers for Use in Companion Cat Play: Association with Guardian-Reported Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Guardians and Cats (Descriptive Statistics)

3.2. Cat Guardians’ Experience with Behavior Problems

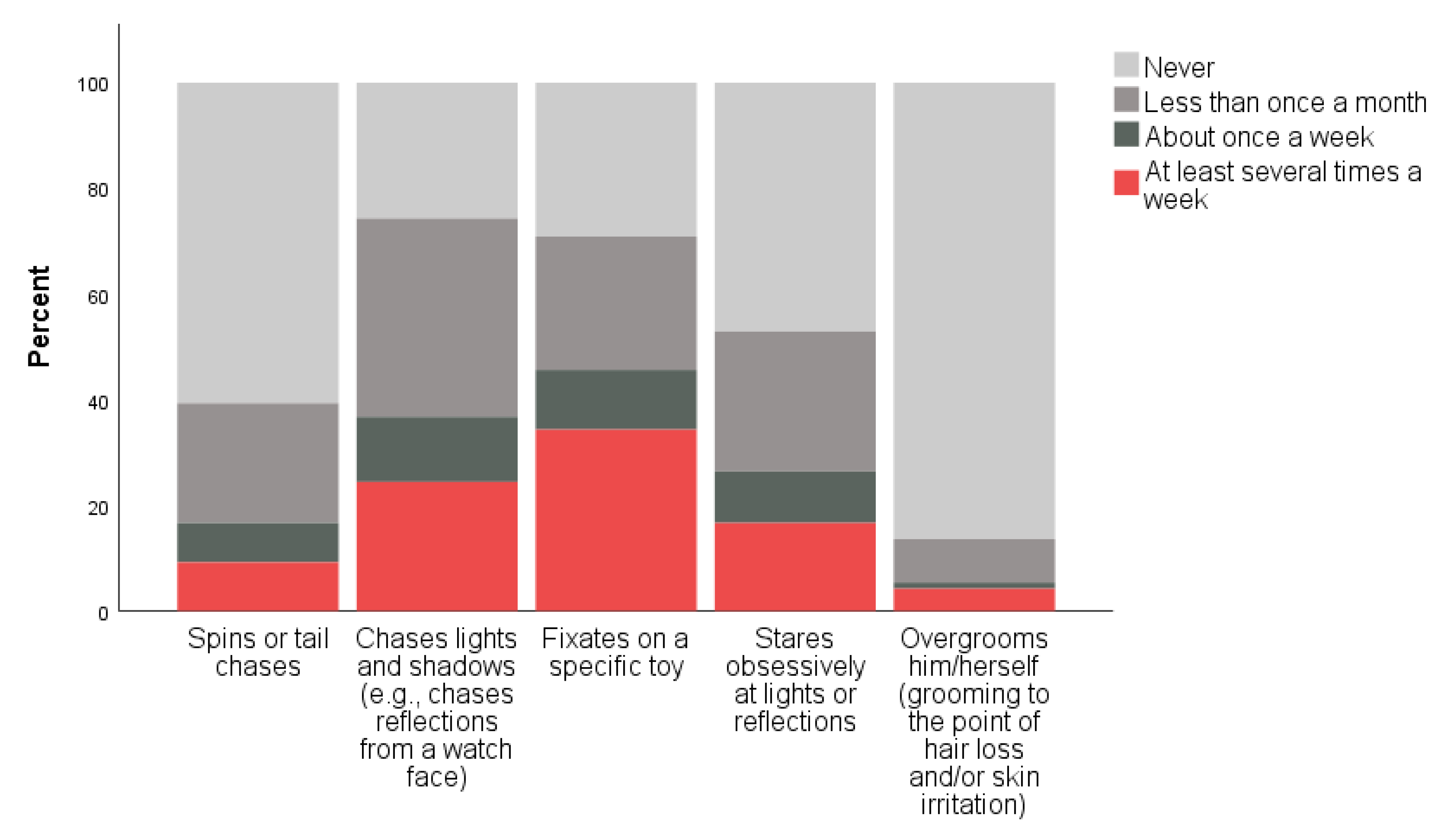

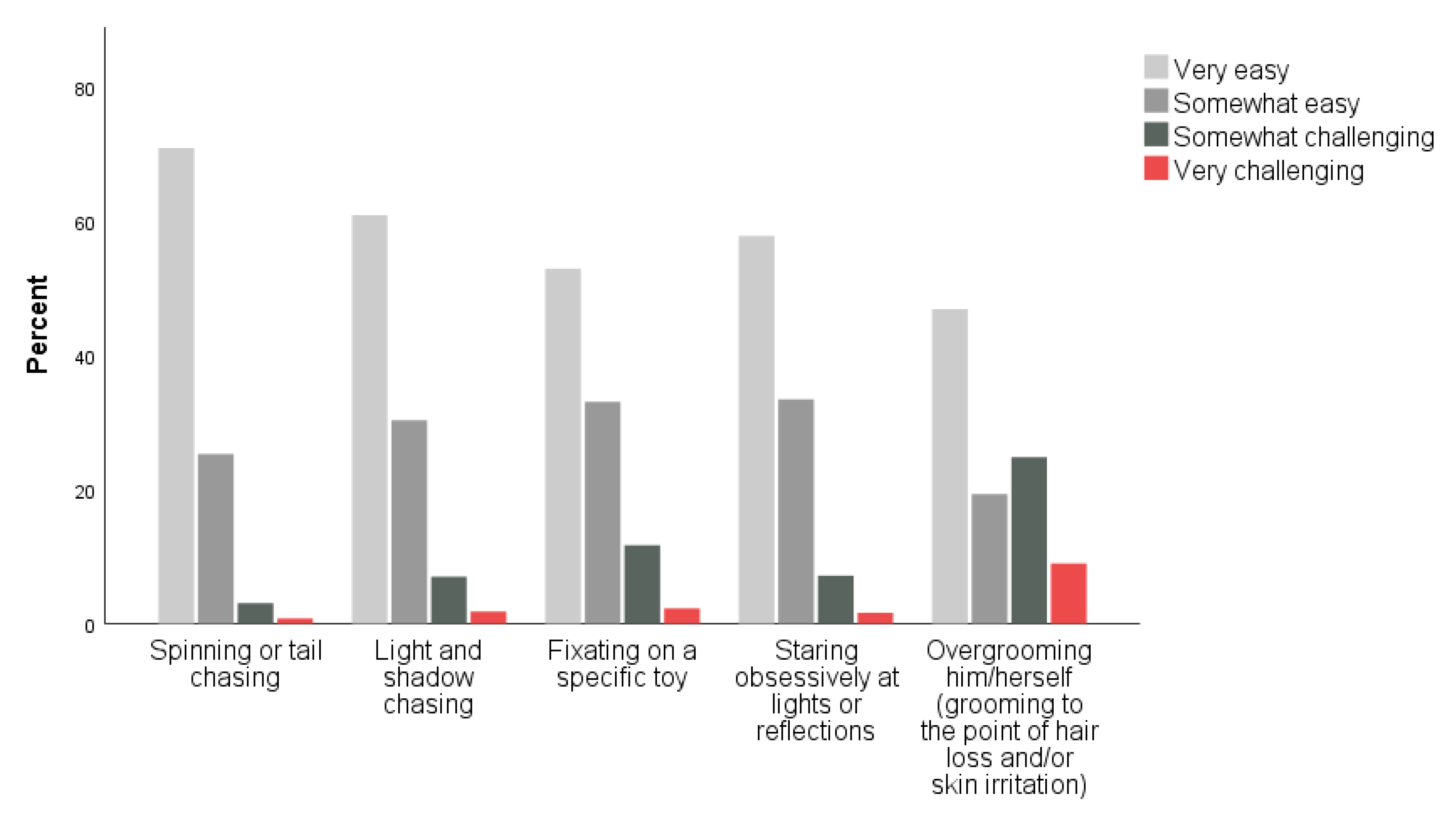

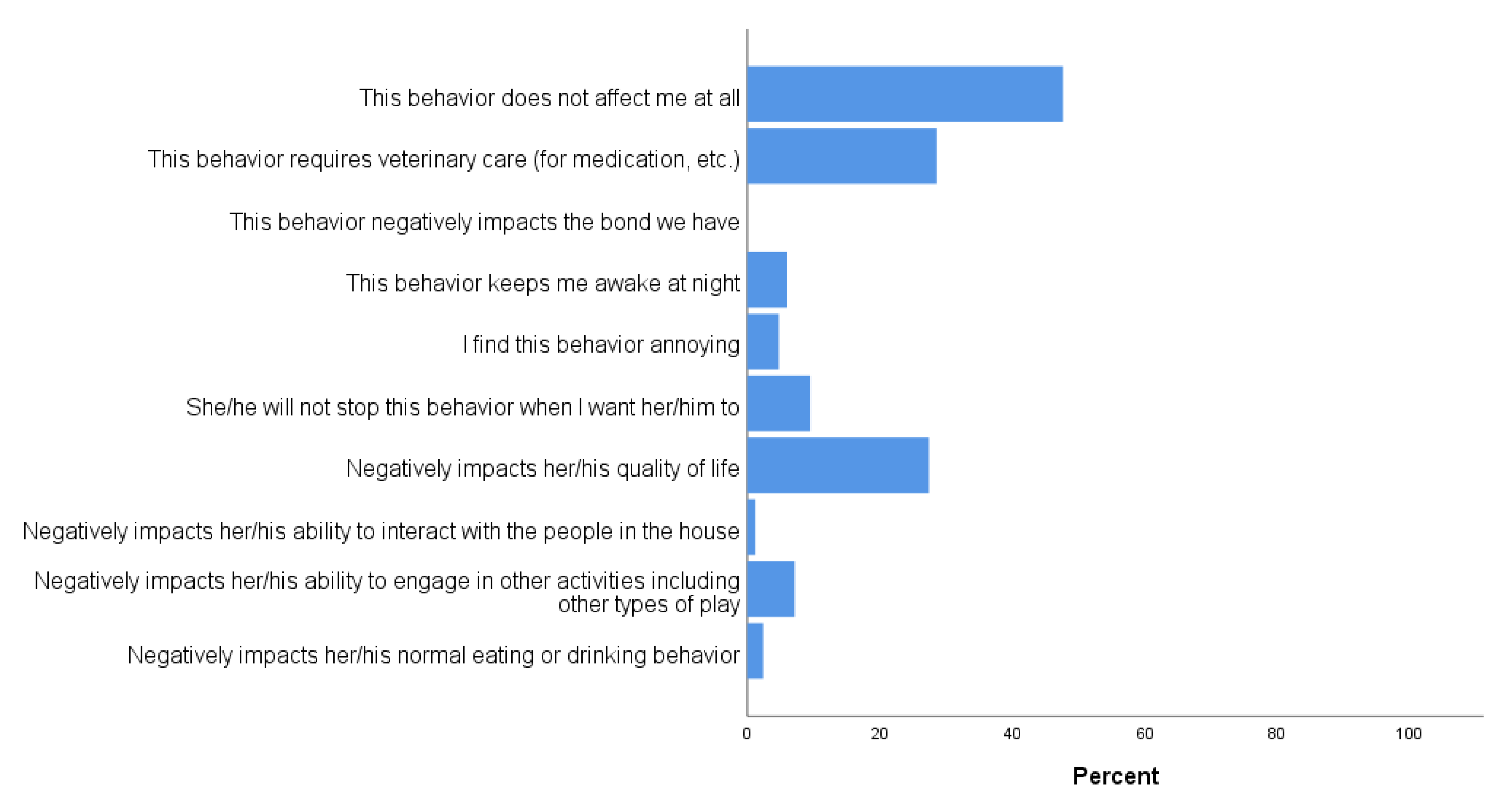

3.3. Reported Behaviors and Guardians’ Responses

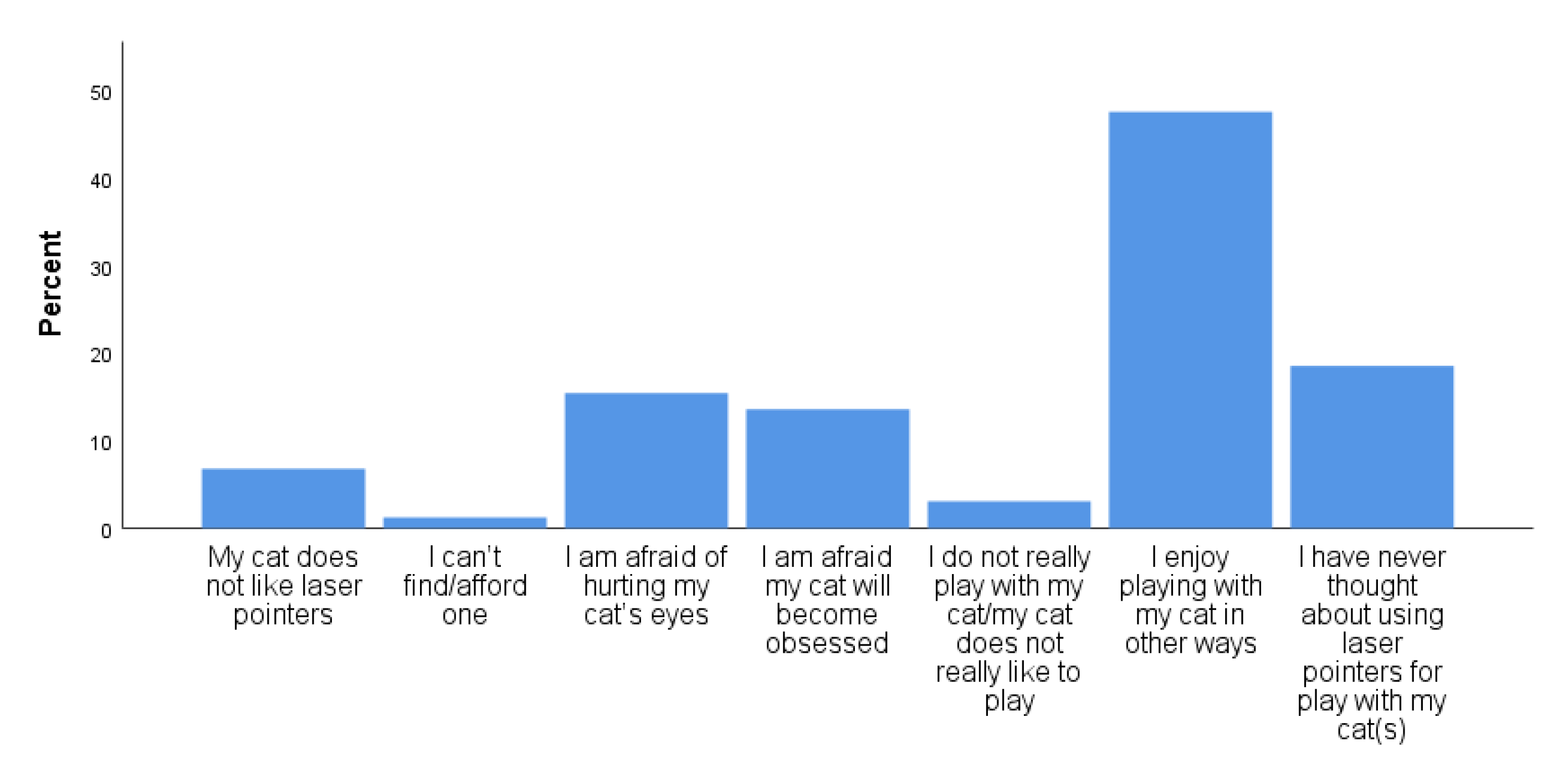

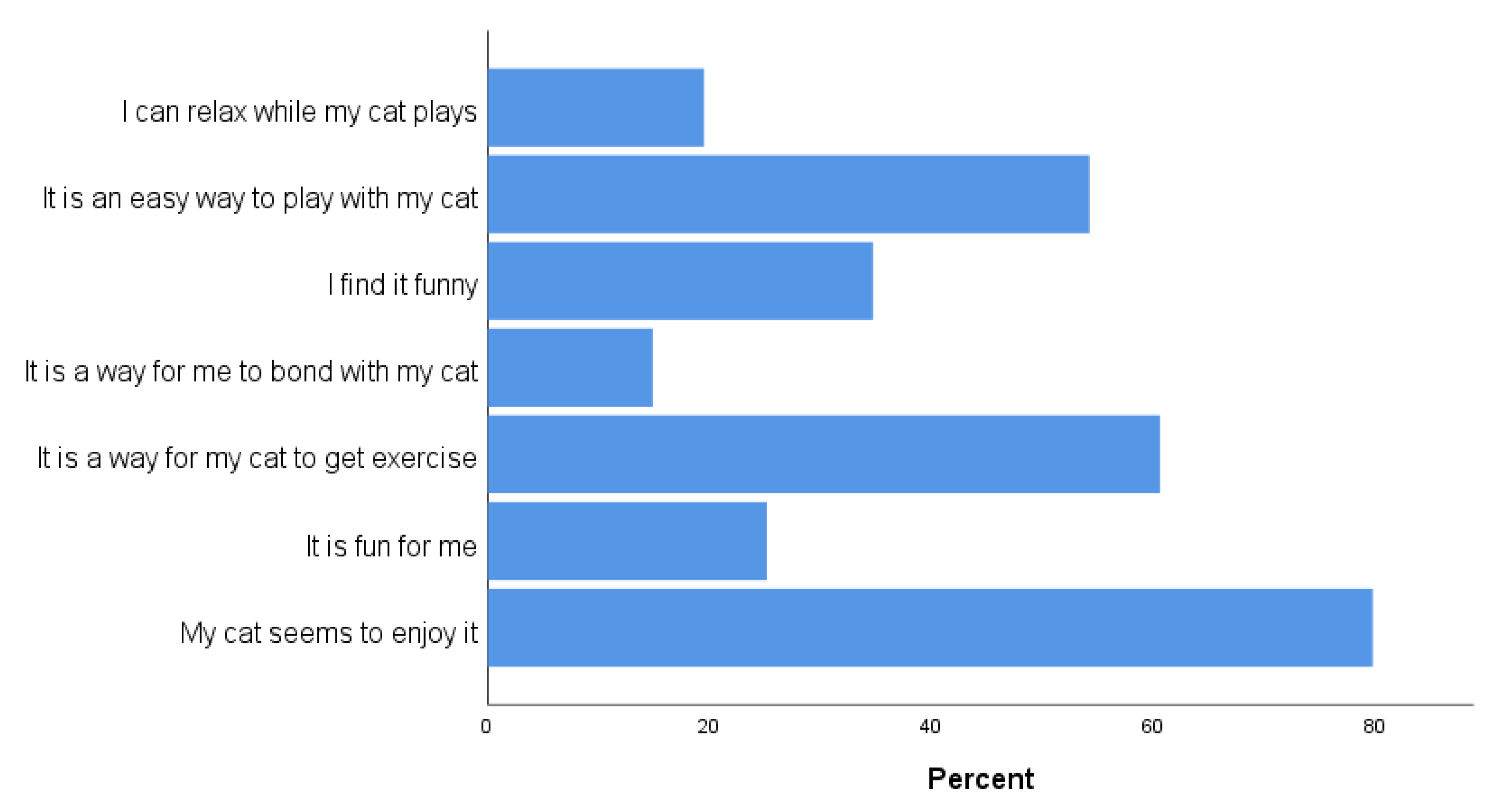

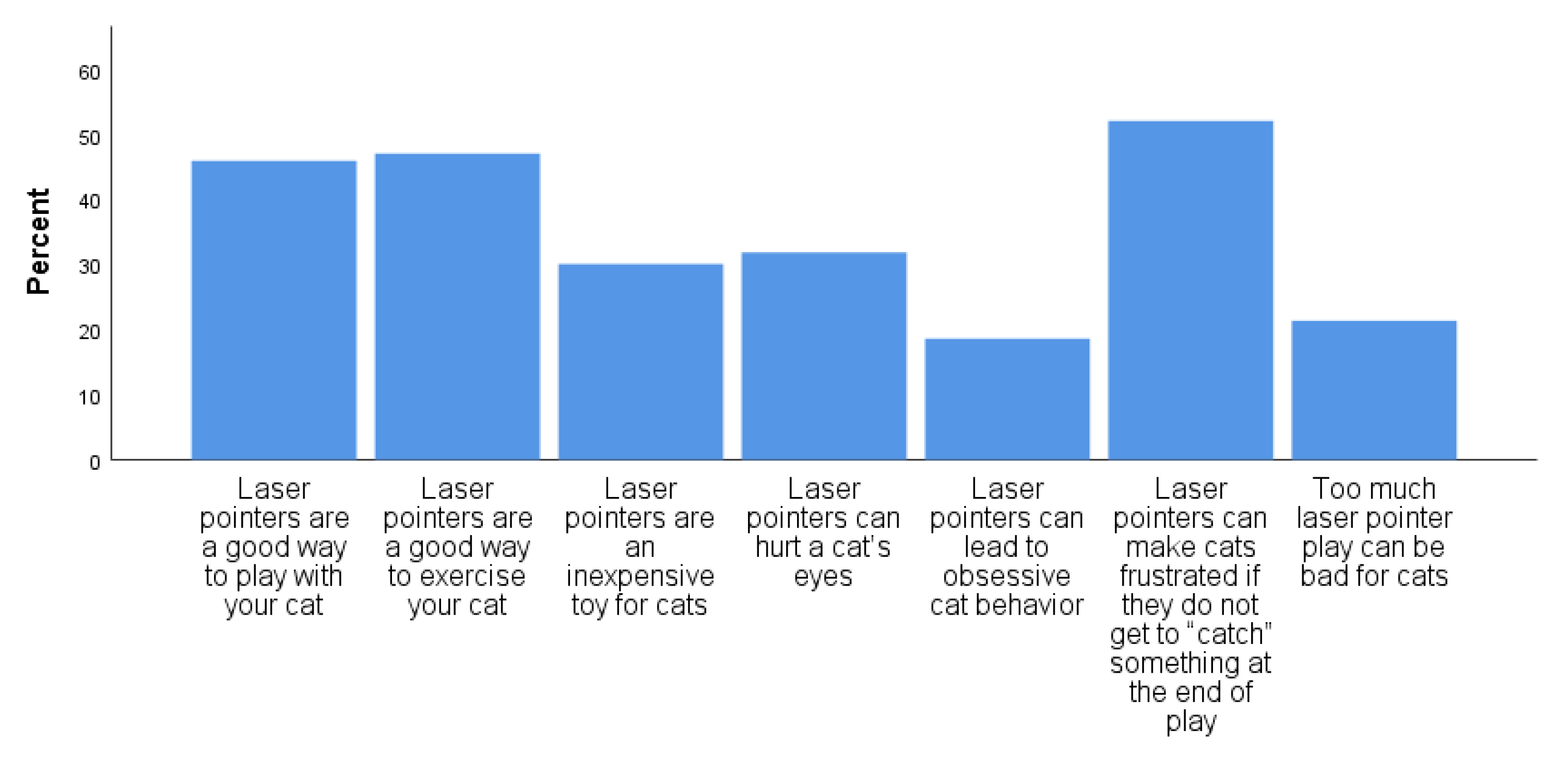

3.4. Cat Guardians’ Reported Use and Perceptions of Laser Light Pointers

3.5. Associations between Exaggerated or Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors and Laser Light Play, Cat Guardian, Cat, and Household Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ellis, S.L.H.; Rodan, I.; Carney, H.C.; Heath, S.; Rochlitz, I.; Shearburn, L.D.; Sundahl, E.; Westropp, J.L. AAFP and ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2013, 15, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, I. It’s Alive! Why Cats Love Laser Pointers. Psychology Today, 11 January 2011. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mental-mishaps/201101/its-alive-why-cats-love-laser-pointers(accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Tremoulet, P.D.; Feldman, J. Perception of Animacy from the Motion of a Single Object. Perception 2000, 29, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremoulet, P.D.; Feldman, J. The Influence of Spatial Context and the Role of Intentionality in the Interpretation of Animacy from Motion. Percept. Psychophys. 2006, 68, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, T.; McCarthy, G.; Scholl, B.J. The Wolfpack Effect: Perception of Animacy Irresistibly Influences Interactive Behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 1845–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amat, M.; Camps, T.; Manteca, X. Stress in Owned Cats: Behavioural Changes and Welfare Implications. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlitz, I. The Welfare of Cats; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Norwell, MA, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-4020-3226-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hewson, C.J.; Luescher, A.U. Compulsive disorders in dogs. In Readings in Companion Animal Behavior; Voith, V.L., Borchelt, P.L., Eds.; Veterinary Learning Systems: Trenton, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Luescher, A.U. Diagnosis and Management of Compulsive Disorders in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2003, 33, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynes, V.V.; Sinn, L. Abnormal repetitive behaviors in dogs and cats: A guide for practitioners. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2014, 44, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overall, K.L. Manual of Clinical Behavioral Medicine of Dogs and Cat; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buffington, C.A.T.; Westropp, J.L.; Chew, D.J.; Bolus, R.R. Clinical Evaluation of Multimodal Environmental Modification (MEMO) in the Management of Cats with Idiopathic Cystitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2006, 8, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinke, C.M.; Godijn, L.M.; van der Leij, W.J.R. Will a Hiding Box Provide Stress Reduction for Shelter Cats? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 160, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delgado, M.; Hecht, J. A review of the development and functions of cat play, with future research considerations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 214, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Cat Care. Playing with Your Cat. 2018. Available online: https://icatcare.org/advice/playing-with-your-cat/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Hall, S.L.; Bradshaw, J.W.S.; Robinson, I.H. Object Play in Adult Domestic Cats: The Roles of Habituation and Disinhibition. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 79, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, M.E.; Buffington, C.A.T. Environmental Enrichment for Indoor Cats. Compend. Contin. Educ. Vet. 2010, 32, E4. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, E.R. Returning a Recently Adopted Companion Animal: Adopters’ Reasons for and Reactions to the Failed Adoption Experience. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2005, 8, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moon-Fanelli, A.A.; Dodman, N.H. Description and Development of Compulsive Tail Chasing in Terriers and Response to Clomipramine Treatment. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1998, 212, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Amat, M.; de la Torre, J.L.R.; Fatjó, J.; Mariotti, V.M.; Wijk, S.V.; Manteca, X. Potential Risk Factors Associated with Feline Behaviour Problems. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 121, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafer, R.; Lago, D.; Wamboldt, P.; Harrington, F. The Pet Relationship Scale: Replication of Psychometric Properties in Random Samples and Association with Attitudes toward Wild Animals. Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, L.S.; Moon-Fanelli, A.A.; Dodman, N.H. Psychogenic Alopecia in Cats: 11 Cases (1993–1996). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1999, 214, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg, G.; Hunthausen, W.; Ackerman, L. Behavior Problems of the Dog and Cat, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe-Aldridge, P.; Rodan, I.; Rose, C.; Thomas, C. Environment Enhancement of Indoor Cats Position Statement. Available online: https://catvets.com/guidelines/position-statements/environment-enhancement-indoor-cats (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- International Cat Care. Outdoor Cats. 2018. Available online: https://icatcare.org/advice/outdoor-cats/ (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Sandøe, P.; Nørspang, A.; Forkman, B.; Bjornvad, C.; Kondrup, S.V.; Lund, T. The Burden of Domestication: A Representative Study of Welfare in Privately Owned Cats in Denmark. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, S. Common feline problem behaviours: Unacceptable indoor elimination. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 21, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekcharoensuk, C.; Osborne, C.A.; Lulich, J.P. Epidemiologic study of risk factors for lower urinary tract diseases in cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.R.; Sanson, R.L.; Morris, R.S. Elucidating the risk factors of feline lower urinary tract disease. N. Z. Vet. J. 1997, 45, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sævik, B.K.; Trangerud, C.; Ottesen, N.; Sørum, H.; Eggertsdóttir, A.V. Causes of lower urinary tract disease in Norwegian cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2011, 13, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, E.K.; Kogan, L.R.; van Haaften, K.; Kolus, S. Cat owners’ perceptions of psychoactive medications, supplements and pheromones for the treatment of feline behavior problems. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018, 21, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassink-van der Schot, A.A.; Day, C.; Morton, J.M.; Rand, J.; Phillips, C.J.C. Risk Factors for Behavior Problems in Cats Presented to an Australian Companion Animal Behavior Clinic. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 14, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herzog, H.A. Gender Differences in Human-Animal Interactions: A Review. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Human Participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | United States | United Kingdom | Canada | Australia | Other |

| 405 (65.5%) | 86 (13.9%) | 52 (8.4%) | 10 (1.6%) | 65 (10.5%) | |

| Age | 18–29 years | 30–39 years | 40–49 years | 50 and older | |

| 149 (24.2%) | 184 (29.9%) | 137 (22.2%) | 146 (23.7%) | ||

| Gender | Female | Male | Non-binary | NA | |

| 547 (88.5%) | 47 (7.6%) | 21 (3.4%) | 3 (0.5%) | ||

| Education | High school/GED or College qualification (e.g., A/AS level, Nat cert/diploma) | Some college | University Degree (e.g., BS, BA, BSc/BSc (Hons)) | Higher degree (e.g., MS, MA, MSc/PhD) | NA/Other |

| 44 (7.1%) | 73 (11.8%) | 196 (31.7%) | 290 (46.9%) | 15 (2.4%) | |

| Length of ownership | 6 months but less than 1 year | At least 1 year but less than 3 years | At least 3 years but less than 5 years | 5 years or longer | |

| 32 (5.2%) | 154 (24.9%) | 116 (18.8%) | 316 (51.1%) | ||

| Cats | |||||

| Cats in the home | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 or more |

| 281 (45.5%) | 207 (33.5%) | 77 (12.5%) | 27 (4.4%) | 26 (4.3%) | |

| Age | 1–2 years | 3–4 years | 5–7 years | 8–10 years | Older than 10 years |

| 98 (15.9%) | 130 (21.0%) | 157 (25.4%) | 85 (13.8%) | 148 (23.9%) | |

| Sex | Male, neutered | Male, intact | Female, spayed | Female, intact | NA |

| 309 (50.1%) | 4 (0.6%) | 300 (48.6%) | 4 (0.6%) | 1 | |

| Indoor/outdoor | Indoor | Indoor/outdoor | Outdoor | ||

| 469 (75.9%) | 148 (23.9%) | 1 (0.2%) | |||

| Declaw status | Declawed, front only | Declawed, front and back | Not declawed | ||

| 32 (5.2%) | 8 (1.3%) | 578 (93.5%) | |||

| Play (Excluding Laser Light Play) (n = 564) | Laser Light Play (n = 290) | Cuddling/Petting (n = 586) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 5 min | 73 (12.9) | 214 (73.8) | 2 (0.3) |

| 5–15 min | 195 (34.6) | 60 (20.7) | 29 (4.9) |

| 16–30 min | 155 (27.5) | 13 (4.5) | 42 (7.2) |

| 31–59 min | 82 (14.5) | 2 (0.7) | 60 (10.2) |

| 1–2 h | 51 (9.0) | 1 (0.3) | 214 (36.5) |

| 3–5 h | 7 (1.2) | 0 | 165 (28.2) |

| More than 5 h | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 74 (12.6) |

| Play (Excluding Laser Light Play) (n = 574) | Laser Light Play (n = 297) | Cuddling/Petting (n = 582) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I feel much less bonded | 1 (0.2) | 7 (2.4) | 3 (0.5) |

| I feel somewhat less bonded | 5 (0.9) | 15 (5.1) | 0 |

| No change in how bonded I feel | 125 (21.8) | 147 (49.5) | 15 (2.6) |

| I feel somewhat more bonded | 209 (36.4) | 100 (33.7) | 65 (11.2) |

| I feel much more bonded | 234 (40.8) | 28 (9.4) | 499 (85.7) |

| H (df) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Spins or tail chases | 7.89 (3) | =0.049 |

| Chases lights and shadows | 52.03 (3) | <0.001 |

| Fixates on a specific toy | 11.46 (3) | =0.009 |

| Stares obsessively at lights or reflections | 28.31 (3) | <0.001 |

| Overgrooms him/herself | 1.41 (3) | =0.704 |

| Spins or Tail Chases | ||||

| Never | Less Than Once a Month | About Once a Week | Several Times a Week | |

| Laser play | ||||

| Never used | 114 (70%) | 22 (14%) | 12 (7%) | 14 (9%) |

| Used to use | 102 (59%) | 51 (29%) | 11 (6%) | 10 (6%) |

| Less than once a month | 125 (56%) | 54 (24%) | 20 (9%) | 26 (12%) |

| More than once a month | 34 (60%) | 13 (23%) | 3 (5%) | 7 (12%) |

| Chases Lights and Shadows | ||||

| Never | Less Than Once a Month | About Once a Week | Several Times a Week | |

| Never used | 76 (47%) | 56 (35%) | 11 (7%) | 19 (12%) |

| Used to use | 38 (22%) | 82 (47%) | 18 (10%) | 36 (21%) |

| Less than once a month | 38 (17%) | 81 (36%) | 37 (16%) | 69 (31%) |

| More than once a month | 7 (12%) | 13 (23%) | 10 (18%) | 27 (47%) |

| Fixates on a Specific Toy | ||||

| Never | Less than ONCE a Month | About Once a Week | Several Times a Week | |

| Never used | 63 (39%) | 44 (27%) | 13 (8%) | 42 (26%) |

| Used to use | 49 (28%) | 44 (25%) | 18 (10%) | 63 (36%) |

| Less than once a month | 55 (24%) | 58 (26%) | 30 (13%) | 82 (36%) |

| More than once a month | 13 (23%) | 10 (18%) | 9 (16%) | 25 (44%) |

| Stares Obsessively at Lights or Reflections (n = 618) | ||||

| Never | Less Than Once a Month | About Once a Week | Several Times a Week | |

| Never used | 109 (67%) | 27 (17%) | 9 (6%) | 17 (11%) |

| Used to use | 78 (45%) | 51 (29%) | 22 (13%) | 23 (13%) |

| Less than once a month | 86 (38%) | 73 (32%) | 23 (10%) | 43 (19%) |

| More than once a month | 18 (32%) | 13 (23%) | 6 (11%) | 20 (35%) |

| Overgrooming | ||||

| Never | Less Than Once a Month | About Once a Week | Several Times a Week | |

| Never used | 144 (89%) | 12 (7%) | 4 (3%) | 2 (1%) |

| Used to use | 148 (85%) | 12 (7%) | 2 (1%) | 12 (7%) |

| Less than once a month | 194 (86%) | 21 (9%) | 1 (0.5%) | 9 (4%) |

| More than once a month | 48 (84%) | 6 (11%) | 0 | 3 (5%) |

| ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Squares | F | Sig. | |

| Regression Residual Total | 848.53 5243.12 6091.66 | 10 604 614 | 78.92 8.68 | 9.78 | <0.001 | |

| Coefficients * (Dependent Variable: reported frequency of ARBs) | ||||||

| Variable | Coefficient (B) | Std. Error | t | Sig. | ||

| (Constant) | 11.08 | 1/26 | 8/80 | <0.001 | ||

| Amount of laser (LLP) toy play | 0.79 | 0.13 | 6.16 | <0.001 | ||

| Guardian age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.51 | 0.027 | ||

| Guardian gender | 0.34 | 0.25 | 1.34 | 0.180 | ||

| Guardian education level | −0.19 | 0.12 | −1.53 | 0.126 | ||

| Cat sex | −0.08 | 0.12 | −0.63 | 0.528 | ||

| Cat age | −0.44 | 0.12 | −3.63 | <0.001 | ||

| Indoor/Outdoor | −0.65 | 0.29 | −2.29 | 0.022 | ||

| Declaw status | −0.04 | 0.27 | −1.6 | 0.880 | ||

| Number of cats in household | −0.22 | 0.16 | −1.36 | 0.176 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kogan, L.R.; Grigg, E.K. Laser Light Pointers for Use in Companion Cat Play: Association with Guardian-Reported Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors. Animals 2021, 11, 2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082178

Kogan LR, Grigg EK. Laser Light Pointers for Use in Companion Cat Play: Association with Guardian-Reported Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors. Animals. 2021; 11(8):2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082178

Chicago/Turabian StyleKogan, Lori R., and Emma K. Grigg. 2021. "Laser Light Pointers for Use in Companion Cat Play: Association with Guardian-Reported Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors" Animals 11, no. 8: 2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082178

APA StyleKogan, L. R., & Grigg, E. K. (2021). Laser Light Pointers for Use in Companion Cat Play: Association with Guardian-Reported Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors. Animals, 11(8), 2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082178