Behaviour in Slower-Growing Broilers and Free-Range Access on Organic Farms in Sweden

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Farms and Flocks

2.1.1. Farmer Interviews

2.1.2. Indoor Observations

2.1.3. Outdoor Observations

2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Indoor Observations

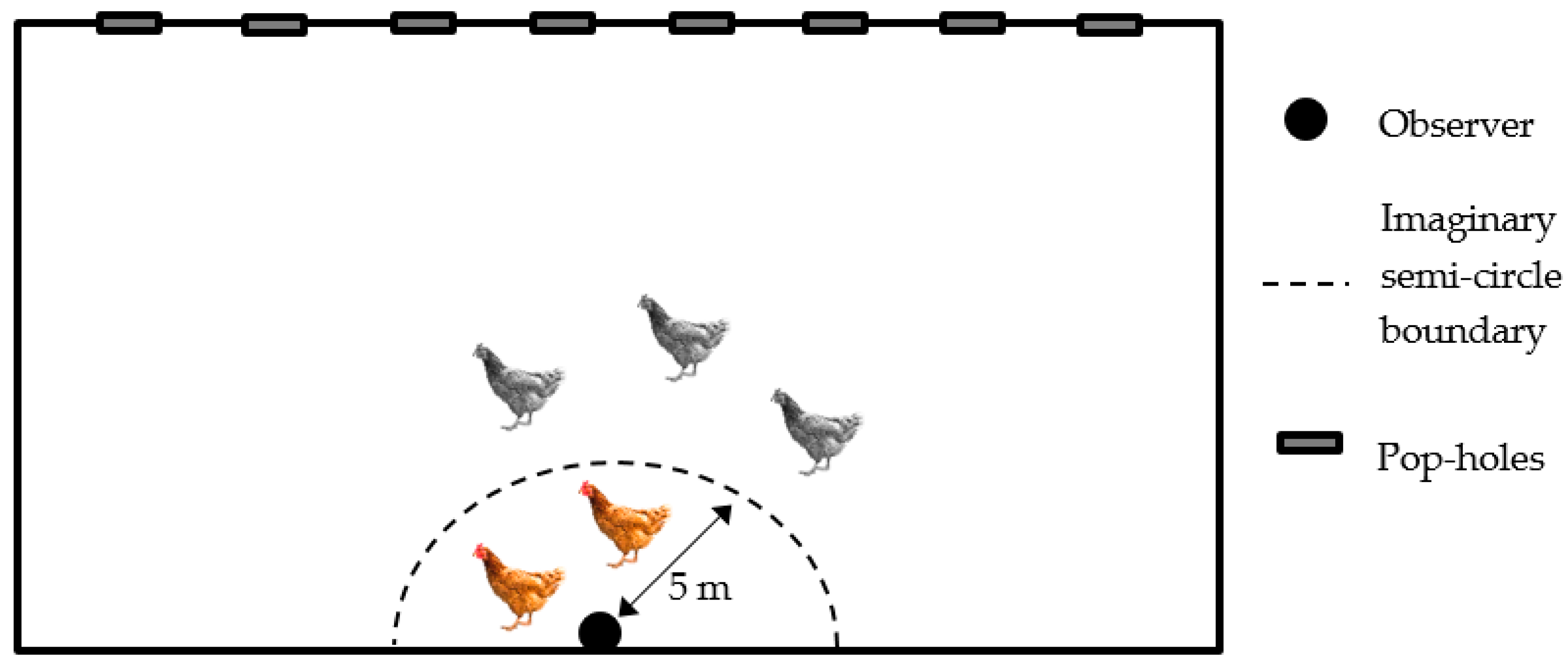

3.1.1. Avoidance Distance Test (Fearfulness)

3.1.2. Behavioural Observations in Rearing Compartment

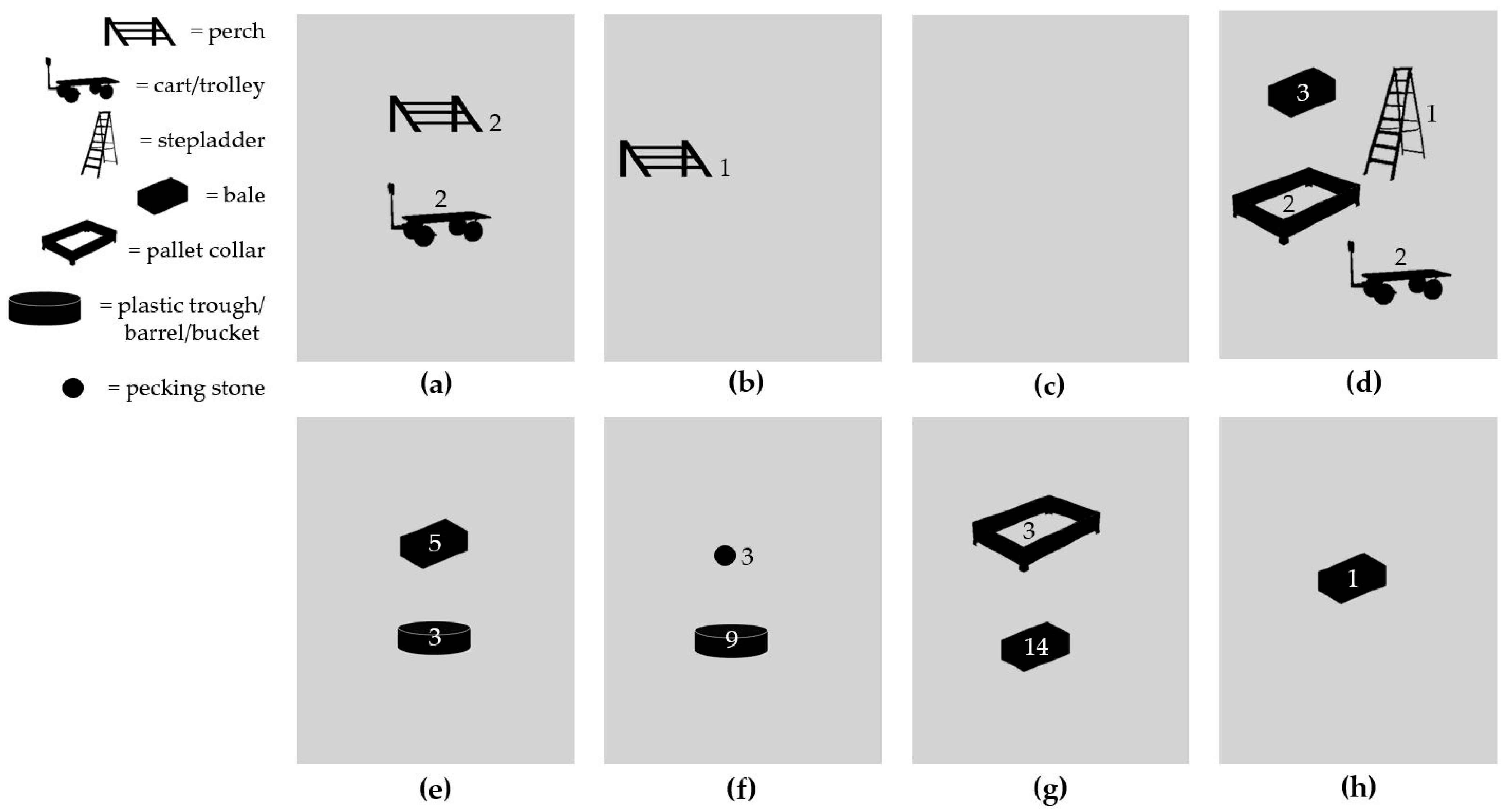

3.1.3. Environmental Enrichment

3.1.4. Behavioural Observations at Pop-Holes

3.2. Outdoor Observations

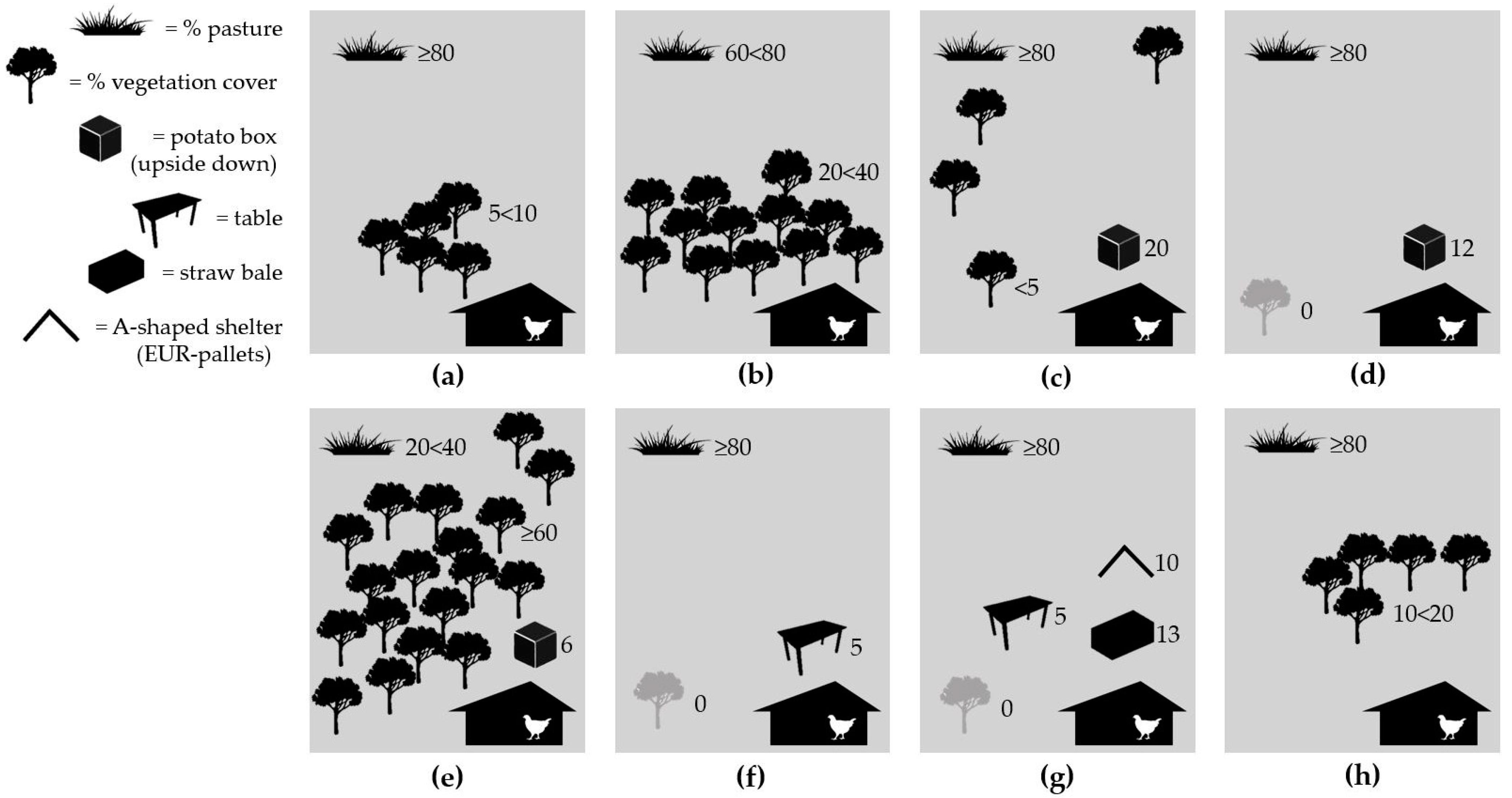

3.2.1. Free-Range Features

3.2.2. Free-Ranging Behaviour in Chickens

3.2.3. Predation

4. Discussion

4.1. Indoor Observations

4.1.1. Avoidance Distance Test (Fearfulness)

4.1.2. Behaviour in Rearing Compartment

4.1.3. Environmental Enrichment

4.1.4. Behaviour at Pop-Holes

4.2. Outdoor Observations

4.2.1. Chicken Free-Ranging and Free-Range Features

4.2.2. Predation

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questions | ||

|---|---|---|

| General information | Hybrid | Rowan Ranger □ Hubbard □ Other: |

| Organic production | Since year: Conventional before: □ Yes □ No If yes, since year: | |

| Buildings | New □ Rebuilt □ | |

| Maximum capacity (number of birds): | ||

| Same number of birds winter-/summertime: □ Yes □ No | ||

| Observed flock | Current age: Original number of birds: Current number of birds: Current average body weight: | |

| Hatching and young chicks | Hatching | On-farm □ or day-old chicks □ If on-farm hatching, brooding days: Name of hatchery: Distance transported: |

| Arrival rooms | □ Yes □ No If yes, age when moved to rearing room: If yes, method for moving to rearing room: | |

| Indoor environment | Temperature scheme (°C): Natural light: □ Yes □ No Artificial light scheme (hours): | |

| Medical treatments | Vaccinations: □ Yes □ No If yes, what: Other medical treatments: □ Yes □ No If yes, what: | |

| Critical points | □ Yes □ No If yes, age(s) or phase(s): Measures of prevention: | |

| Housing (rearing compartment) | Indoor environment | Temperature (°C): Natural (N) light: □ Yes □ No Artificial (A) light type: Night time (A) (hours): Dusk and dawn simulated (A): □ Yes □ No If yes, time/duration: Litter type: Underfloor heating: □ Yes □ No |

| Air quality | Ventilation type: Ammonia monitoring: Ammonia regulation: | |

| Environmental enrichment | Object(s): Amount/number: Distribution: Time of year provided: Age of installation: | |

| Roughage | Type(s): Supplier: Amount: Distribution: Time of year provided: | |

| Production | Mortality | This flock (%): Average (%): Main reasons: |

| Culling | Average number of birds: Main reasons: | |

| Hatching | % of eggs discarded/not hatched: | |

| Slaughter | Thinning: □ Yes □ No Age(s): Abattoir: Distance transported: Harvesting: Trained team □ Selves □ Comments on harvesting: | |

| Growth | Expected average slaughter weight: Average daily weight gain: Feed conversion rate: | |

| Feed specifics | Supplier: Starter (type and age period): Rearing (type and age period): Finisher: (type and age period): | |

| Outdoor area | Free-range access (pop-holes/curtain open) | From age: Hours per day: Months per year: Weather conditions: |

| Birds’ free-ranging behaviour | Age when first ranging: Weather conditions preferred by chickens: Weather conditions disliked by chickens: Average distance from house (m): Maximum distance from house (m): | |

| Predators | Problem: □ Yes □ No If yes, what species: Measures of prevention: | |

| Free-range characteristics | Area: Vegetation: Natural □ Planted □ |

References

- International Federation of Organic Movement (IFOAM)-Organics International. Available online: https://www.ifoam.bio/why-organic/principles-organic-agriculture/principle-fairness (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Fraser, D.; Weary, D.M.; Pajor, E.A.; Milligan, B.N. A Scientific Conception of Animal Welfare that Reflects Ethical Concerns. Anim. Welf. 1997, 6, 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 889/2008 of 5 September 2008 Laying down Detailed Rules for the Implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products with Regard to Organic Production, Labelling and Control. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/889/oj (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Nielsen, B.L.; Thomsen, M.G.; Sørensen, P.; Young, J.F. Feed and strain effects on the use of outdoor areas by broilers. Br. Poult. Sci. 2003, 44, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawkins, M.S.; Cook, P.A.; Whittingham, M.J.; Mansell, K.A.; Harper, A.E. What makes free-range broiler chickens range? In situ measurement of habitat preference. Anim. Behav. 2003, 66, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fanatico, A.C.; Mench, J.A.; Archer, G.S.; Liang, Y.; Gunsaulis, V.B.B.; Owens, C.M.; Donoghue, A.M. Effect of outdoor structural enrichments on the performance, use of range area, and behavior of organic meat chickens. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Feber, R.; Hemery, G.; Cook, P.; James, K.; Lamberth, C.; Dawkins, M. Welfare and environmental benefits of integrating commercially viable free-range broiler chickens into newly planted woodland: A UK case study. Agric. Syst. 2007, 94, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durali, T.; Groves, P.; Cowieson, A.J.; Singh, M. Evaluating Range Usage of Commerical Free Range Broilers and Its Effect on Bird Performance Using Radi Frequency Identification (RFID) Technology. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium, Sydney, Australia, 16–19 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm, C.; Karlsson, L.; Johansson, A.; Altimiras, J. Higher fear of predators does not decrease outdoor range use in free-range Rowan Ranger broiler chickens. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. A-Anim. Sci. 2016, 66, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.S.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Groves, P.J.; Gebhardt-Henrich, S.G.; Rault, J.-L. Ranging Behaviour of Commercial Free-Range Broiler Chickens 1: Factors Related to Flock Variability. Animals 2017, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mirabito, L.; Joly, T.; Lubac, S. Impact of the presence of peach tree orchards in the outdoor hen runs on the occupation of the space by Red Label’ type chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2001, 42, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.S.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Groves, P.J.; Gebhardt-Henrich, S.G.; Rault, J.-L. Ranging Behaviour of Commercial Free-Range Broiler Chickens 2: Individual Variation. Animals 2017, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stadig, L.M.; Rodenburg, T.B.; Ampe, B.; Reubens, B.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Effect of free-range access, shelter type and weather conditions on free-range use and welfare of slow-growing broiler chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 192, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KRAV. Regler för KRAV-Certifierad Produktion-Utgåva 2021. Standards for KRAV-Certified Production-2021 Edition. Available online: https://www.krav.se/en/standards/download-krav-standards/ (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 of 28 June 2007 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products and Repealing Regulation (EEC) No 2092/91. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32007R0834 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Wallenbeck, A.; Wilhelmsson, S.; Jönsson, L.; Gunnarsson, S.; Yngvesson, J. Behaviour in one fast-growing and one slower-growing broiler (Gallus gallus domesticus) hybrid fed a high- or low-protein diet during a 10-week rearing period. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. A—Anim. Sci. 2016, 66, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokkers, E.A.M.; Koene, P. Behaviour of fast- and slow growing broilers to 12 weeks of age and the physical consequences. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 81, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellini, C.; Mugnai, C.; Moscati, L.; Mattioli, S.; Amato, M.G.; Mancinelli, A.C.; Dal Bosco, A. Adaptation to organic rearing system of eight different chicken genotypes: Behaviour, welfare and performance. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 15, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, S.; Schwarzer, A.; Wilutzky, K.; Louton, H.; Bachmeier, J.; Schmidt, P.; Erhard, M.; Rauch, E. Behavior as welfare indicator for the rearing of broilers in an enriched husbandry environment—A field study. J. Vet. Behav. 2017, 19, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.M. Slow and steady wins the race: The behaviour and welfare of commercial faster growing broiler breeds compared to a commercial slower growing breed. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawkins, M.S. Time budgets in Red Junglefowl as a baseline for the assessment of welfare in domestic fowl. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1989, 24, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SJVFS 2020:1. Föreskrifter om ändring i Statens jordbruksverksföreskrifter (SJVFS 2015:29) om ekologisk produktion och kontroll av ekologisk produktion. In The Swedish Board of Agriculture’s Regulations on Organic Production and Control of Organic Production; The Swedish Board of Agriculture: Jönköping, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan Ranger Broiler: Performance Objectives 2018, Rowan Range, Aviagen. Available online: http://eu.aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/Rowan_Range//RowanRanger-Broiler-PO-18-EN.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Hubbard, Hubbard SAS, Quintin, France. Available online: https://www.hubbardbreeders.com/ (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- The Swedish Board of Agriculture. Statistiska meddelanden: Ekologisk djurhållning 2019. In Statistical Report: Organic Livestock 2019; The Swedish Board of Agriculture: Jönköping, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Aurrekoetxea, A.; Leone, E.H.; Estevez, I. Effects of panels and perches on the behaviour of commercial slow-growing free-range meat chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 165, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SJVFS 2019:9. Case no L 150. Statens jordbruksverks föreskrifter och allmänna råd om försöksdjur. In The Swedish Board of Agriculture’s Regulations on Research Animals; The Swedish Board of Agriculture: Jönköping, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Göransson, L.; Yngvesson, J.; Gunnarsson, S. Bird Health, Housing and Management Routines on Swedish Organic Broiler Chicken Farms. Animals 2020, 10, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welfare Quality®. Welfare Quality® Assessment Protocol For Poultry (Broilers, Laying Hens); Welfare Quality® Consortium: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, B.A.; Siewerdt, F.; Estevez, I. Access to barrier perches improves behavior repertoire in broilers. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daigle, C.L. Chapter 11—Controlling Feather Pecking and Cannibalism in Egg Laying Flocks. In Egg Innovations and Strategies for Improvements, 1st ed.; Hester, P.Y., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M.; Bailie, C.L.; O’Connell, N.E. Play behaviour, fear responses and activity levels in commercial broiler chickens provided with preferred environmental enrichments. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 2019, 13, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, P.; Bateson, P. Measuring Behaviour. An Introductory Guide, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- SMHI Väder. The Swedish Meterological and Hydrological Institute (Version 4.0.9). Mobile Application Software. Available online: https://www.apple.com/se/app-store/ (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Jones, R.B. Regular handling and the domestic chick’s fear of human beings: Generalisation of response. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1994, 42, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.L.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Jones, R.B. Behavioural responses of commercially farmed laying hens to humans: Evidence of stimulus generalization. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 37, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasdal, G.; Moe, R.O.; de Jong, I.C.; Granquist, E.G. The relationship between measures of fear of humans and lameness in broiler chicken flocks. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 2018, 12, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvera, A.M.; Wallenbeck, A.; Butterworth, A.; Blokhuis, H.J. Modification of the human–broiler relationship and its potential effects on production. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. A–Anim. Sci. 2016, 66, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, R.B. Reduction of the domestic chick’s fear of human beings by regular handling and related treatments. Anim. Behav. 1993, 46, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riber, A.; Herskin, M.; Foldager, L.; Berenjian, A.; Sandercock, D.; Murrell, J.; Machado Tahamtani, F. Are changes in behavior of fast-growing broilers with slight gait impairment (GS0-2) related to pain? Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklund, B.; Jensen, P. Domestication effects on behavioural synchronization and individual distances in chickens (Gallus gallus). Behav. Process. 2011, 86, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, G.; Zhao, Y.; Porter, Z.; Purswell, J.L. Automated measurement of broiler stretching behaviors under four stocking densities via faster region-based convolutional neural network. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 15, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, M.; Bailie, C.L.; O’Connell, N.E. An evaluation of potential dustbathing substrates for commercial broiler chickens. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 2018, 12, 1933–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villagrá, A.; Olivas, I.; Althaus, R.; Gómez, E.; Lainez, M.; Torres, A. Behavior of broiler chickens in four different substrates: A choice test. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2014, 16, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newberry, R.C. Environmental enrichment: Increasing the biological relevance of captive environments. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1995, 44, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, I.C.; Gunnink, H. Effects of a commercial broiler enrichment programme with or without natural light on behaviour and other welfare indicators. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 2019, 13, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riber, A.B.; van de Weerd, H.A.; de Jong, I.C.; Steenfeldt, S. Review of environmental enrichment for broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.J.; Wilkins, L.J.; Knowles, T.G.; Booth, F.; Toscano, M.J.; Nicol, C.J.; Brown, S.N. Continuous monitoring of pop hole usage by commercially housed free-range hens throughout the production cycle. Vet. Rec. 2011, 169, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlander-Matauschek, A.; Felsenstein, K.; Niebuhr, K.; Troxler, J. Influence of pop hole dimensions on the number of laying hens outside on the range. Br. Poult. Sci. 2006, 47, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B.O.; Carmichael, N.L.; Walker, A.W.; Grigor, P.N. Low incidence of aggression in large flocks of laying hens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1997, 54, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, C.; Kitessa, S.M.; Barekatain, R.; Drake, K. Determination of range enrichment for improved hen welfare on commercial fixed-range free-range layer farms. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 59, 1336–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeltner, E.; Hirt, H. Factors involved in the improvement of the use of hen runs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegelund, L.; Sørensen, J.T.; Kjær, J.B.; Kristensen, I.S. Use of the range area in organic egg production systems: Effect of climatic factors, flock size, age and artificial cover. Br. Poult. Sci. 2005, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, H.; Cronin, G.; Smith, C.L.; Hemsworth, P.; Rault, J.L. Behaviour of free-range laying hens in distinct outdoor environments. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestman, M.; Bikker-Ouwejan, J. Predation in organic and free-range egg production. Animals 2020, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Behaviour | Description |

|---|---|

| States | |

| Standing | Upright motionless position on extended legs with both feet, but no other body parts touching the ground during ≥2 s |

| Sitting | Positioned with bent legs, hocks resting on the ground and abdomen in contact with the ground |

| Resting | Positioned with sternum in contact with the ground, head lowered and resting on ground or tucked in under own wing, with eyes open, semi- or fully closed |

| Walking | Locomotion starting when bird takes two or more steps forward in succession |

| Perching | Bird standing, sitting or resting positioned on perch or other elevated structure |

| Foraging | Bird lowers its head and manipulates substrate on ground with beak and scratches with feet in search of food, while standing or slowly walking forward with head below rump level |

| Eating | Bird with head above or in feeder, actively consuming feed |

| Drinking | Bird pecking at drinking nipple or consuming water from cup beneath drinking nipple |

| Events | |

| Preening | Manipulation (cleaning, arranging or oiling) of own feathers with beak, while standing or sitting |

| Dust bathing | Bird sitting or lying down in substrate, pecking and scratching at litter material, tossing and distributing loose substrate onto its back and wings, ruffling and shaking its feathers with or without rubbing head against ground |

| Wing stretching | Slowly extending one wing |

| Leg stretching | Slowly extending one leg backwards or laterally |

| Running | Rapid locomotion starting when bird takes two or more steps forward in rapid succession |

| Flying | Locomotion starting when bird extends and flaps wings and moves a distance through the air |

| Gentle feather pecking 1 | Bird uses beak to gently manipulate and lightly peck at feathers of recipient bird, which does not move away |

| Severe feather pecking 1 | Bird uses beak to forcefully manipulate feathers of recipient bird, which moves away from performer bird. Pecks are hard, fast and often singular and may result in detached feathers |

| Aggressive pecking 1 | Bird raises head and uses beak to forcefully stab at recipient bird, which moves away. Pecks usually directed towards the head, but may also be directed at the body |

| Fighting | Two birds standing facing each other, heads and necks raised to the same level, at least one bird forcefully kicking and pecking at conspecific |

| Pop-hole: walking along 2 | Bird walking in pop-hole parallel to its opening, at least three steps in succession |

| Pop-hole: turning back in 2 | Bird walking or running through pop-hole from inside towards outside, but making a halt and change of direction to remain indoors |

| Pop-hole: turning back out 2 | Bird walking or running through pop-hole from outside towards inside, but making a halt and change of direction to remain outdoors |

| Play-like activity 3 | Simulated fighting with jumping, kicking and pecking but without obvious aggression or forceful or injurious contact |

| Sparring 4 | |

| Frolicking 4 | Spontaneous burst of running and/or jumping with wings flapping, with no obvious intention, often with rapid direction changes |

| Food-running 4 | Bird picks up an object and runs with it in beak, often making peeping noises repeatedly, followed by at least one other bird |

| Vocalisations | Sudden loud, sharp, shrill, piercing cry |

| Squawks | |

| Other | All other abnormal, aberrant vocalisations |

| Observation | Description |

|---|---|

| Free-ranging | |

| Birds outdoors | Estimate of total number of birds in free-ranging area |

| Bird dispersion | Estimate of proportion (%) of total number of birds outside at <5, 5 < 10, 10 < 15, 15 < 25 and ≥25 m, respectively |

| Maximum distance | Longest distance from the winter garden to where a bird was observed ranging |

| Free-range features | |

| Pasture: proportion of total free-range area | 0 (very low: <20%); 1 (low: 20 < 40%); 2 (moderate: 40 < 60%); 3 (high: 60 < 80%); 4 (very high: ≥80%) |

| Vegetation cover: proportion of total free-range area 1 | 0 (none: 0%); 1 (extremely low: <5%); 2 (very low: 5 < 10%); 3 (low: 10 < 20%); 4 (moderate: 20 < 40%); 5 (high: 40 < 60%); 6 (very high: ≥60%) |

| Type of vegetation cover | Proportion (%) of total vegetation cover made up of bushes <100 cm, bushes ≥100 cm and trees, respectively |

| Artificial shelter | Description and number of objects, including dimensions as applicable, and an estimate of number of birds beneath |

| Behaviour | Observations of Behaviour (Total Counts) | Observations of Behaviour (Median and Range) per Farm | Total Number of Farms on Which Behaviour Was Observed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gentle feather pecking | 10 | 1 (0–5) | 5 |

| Squawks | 8 | 0 (0–7) | 2 |

| Leg stretching | 6 | 1 (0–2) | 5 |

| Perching | 4 1 | 1 (1–2) | 3 |

| Aggressive pecking | 3 | 0 (0–2) | 2 |

| Wing stretching | 2 | 0 (0–1) | 2 |

| Play-like activity | 2 | 0 (0–2) | 1 |

| Fighting | 1 | 0 (0–1) | 1 |

| Dust bathing | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 |

| Flying | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 |

| Other vocalisations | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 |

| Severe feather pecking | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 |

| Item | Number of Birds on Top of Item per Observation (Median and Range) | Number of Birds Adjacent to Item per Observation (Median and Range) | Total Number of Observations per Item | Number of Farms on Which Observations Were Performed (out of Total Farms Possible) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perches 1 | 16 (13–21) | n/a | 10 | 2 (2) |

| Cart 2 | 15 | 18 | 1 | 1 (2) |

| Pallet collar 3 | 7 (1–13) | 7.5 (5–10) | 2 | 2 (2) |

| Straw bale (large, round) | 6 (4–8) | 25 6 | 4 | 1 (1) |

| Bales (small, square) 4 | 4 (0–6) | 6 (2–11) | 9 | 3 (3) |

| Plastic barrel upside down 5 | 2 (1–4) | 9 (0–12) | 5 | 1 (2) |

| Plastic bucket upside down | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 (1) |

| Eight steps-stepladder | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 (1) |

| Behaviour | Observations of Behaviour (Total Counts) | Total Number of Pop-Holes at Which Behaviour Was Observed | Observations of Behaviour (Median and Range) per Pop-Hole | Total Number of Farms on Which Behaviour Was Observed | Observations of Behaviour (Median and Range) per Farm | Observations of Behaviour (Median and Range) per Meter (Width) Pop-Hole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standing | 243 | 22 | 10 (0–23) | 8 | 23.5 (5–58) | 6.5 (0–13.9 |

| Sitting | 108 | 19 | 3 (0–16) | 8 | 7.5 (1–39) | 1.5 (0–8) |

| Foraging | 90 | 17 | 2 (0–14) | 7 | 7 (0–31) | 1.2 (0–8.5) |

| Preening | 47 | 13 | 1 (0–8) | 7 | 3.5 (0–13) | 0.6 (0–4.9) |

| Turning back in | 21 | 10 | 0 (0–7) | 7 | 1.5 (0–9) | 0 (0–3.5) |

| Running | 20 | 8 | 0 (0–6) | 5 | 1 (0–8) | 0 (0–3) |

| Leg stretching | 15 | 9 | 0 (0–3) | 6 | 1.5 (0–5) | 0 (0–1.5) |

| Walking (along pop-hole) | 11 | 5 | 0 (0–3) | 3 | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–1.8) |

| Gentle feather pecking | 10 | 4 | 0 (0–5) | 4 | 0.5 (0–5) | 0 (0–2.5) |

| Wing stretching | 6 | 6 | 0 (0–1) | 5 | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) |

| Turning back out | 6 | 6 | 0 (0–1) | 3 | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) |

| Aggressive pecking | 2 | 2 | 0 (0–1) | 2 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0.6) |

| Dust bathing | 2 | 2 | 0 (0–1) | 2 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0.6) |

| Resting | 1 | 1 | 0 (0–1) | 1 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0.5) |

| Flying | 0 | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Severe feather pecking | 0 | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Fighting | 0 | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Play-like activity | 0 | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| Farm | Proportion % of Flock FR 1 | Distance (m) from Winter Garden (% of FR Chickens) | Maximum Distance (m) from Winter Garden | Temperature (°C) | Cloud cover | Precipitation | Average Wind Speed 2 (m/s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5 | 5 < 10 | 10 < 15 | 15 < 25 | ≥25 | |||||||

| a | 6 (250) | 10 | 10 | 20 | 55 | 5 | 55 | 10.2 | S | - | 5 (9) |

| b | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 7.5 | C | HR | 5 (9) |

| c | 0.2 (8) | 37.5 | 0 | 0 | 62.5 | 0 | 19 | 12.2 | C | D | 6 (14) |

| d | 1.1 (50) | 20 | 60 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 18 | 16.8 | S(C) | - | 4 (8) |

| e | 3.3 (160) | 12.5 | 31.3 | 37.5 | 12.5 | 6.3 | 33 | 12.2 | S | - | 5 (10) |

| f | 0 (0) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8.3 | S | - | 5 (13) |

| g | 0.8 (40) | 12.5 | 50 | 12.5 | 25 | 0 | 16 | 9.5 | S | - | 6 (14) |

| h 3 | 21.5 (215) | 70 | 9.3 | 4.7 | 7 | 9.3 | 40 | 8.6 | C | D | 9 (19) |

| Farm | Description of Fence |

|---|---|

| a | Chicken wire (height 100 cm); buried 30 cm horizontally underground; slacking considerably in places |

| b | Sheep fence (height 100 cm); square openings 10–12 cm; slacking considerably in places |

| c | Wildlife fence (180–200 cm); ground-level electric fence |

| d | Sheep fence (100 cm); square openings 10–12 cm; slacking considerably in places; not enclosing entire range |

| e | Wildlife fence (180–200 cm) |

| f | Robust wildlife fence (155 cm); mink-proof fence bottom 100 cm, buried 20 cm underground; electric fence at top and ground level |

| g | Wildlife fence (180–200 cm) |

| h | Robust wire fence (height ~150 cm) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Göransson, L.; Gunnarsson, S.; Wallenbeck, A.; Yngvesson, J. Behaviour in Slower-Growing Broilers and Free-Range Access on Organic Farms in Sweden. Animals 2021, 11, 2967. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11102967

Göransson L, Gunnarsson S, Wallenbeck A, Yngvesson J. Behaviour in Slower-Growing Broilers and Free-Range Access on Organic Farms in Sweden. Animals. 2021; 11(10):2967. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11102967

Chicago/Turabian StyleGöransson, Lina, Stefan Gunnarsson, Anna Wallenbeck, and Jenny Yngvesson. 2021. "Behaviour in Slower-Growing Broilers and Free-Range Access on Organic Farms in Sweden" Animals 11, no. 10: 2967. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11102967

APA StyleGöransson, L., Gunnarsson, S., Wallenbeck, A., & Yngvesson, J. (2021). Behaviour in Slower-Growing Broilers and Free-Range Access on Organic Farms in Sweden. Animals, 11(10), 2967. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11102967