Broiler Chicks’ Motivation for Different Wood Beddings and Amounts of Soiling

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

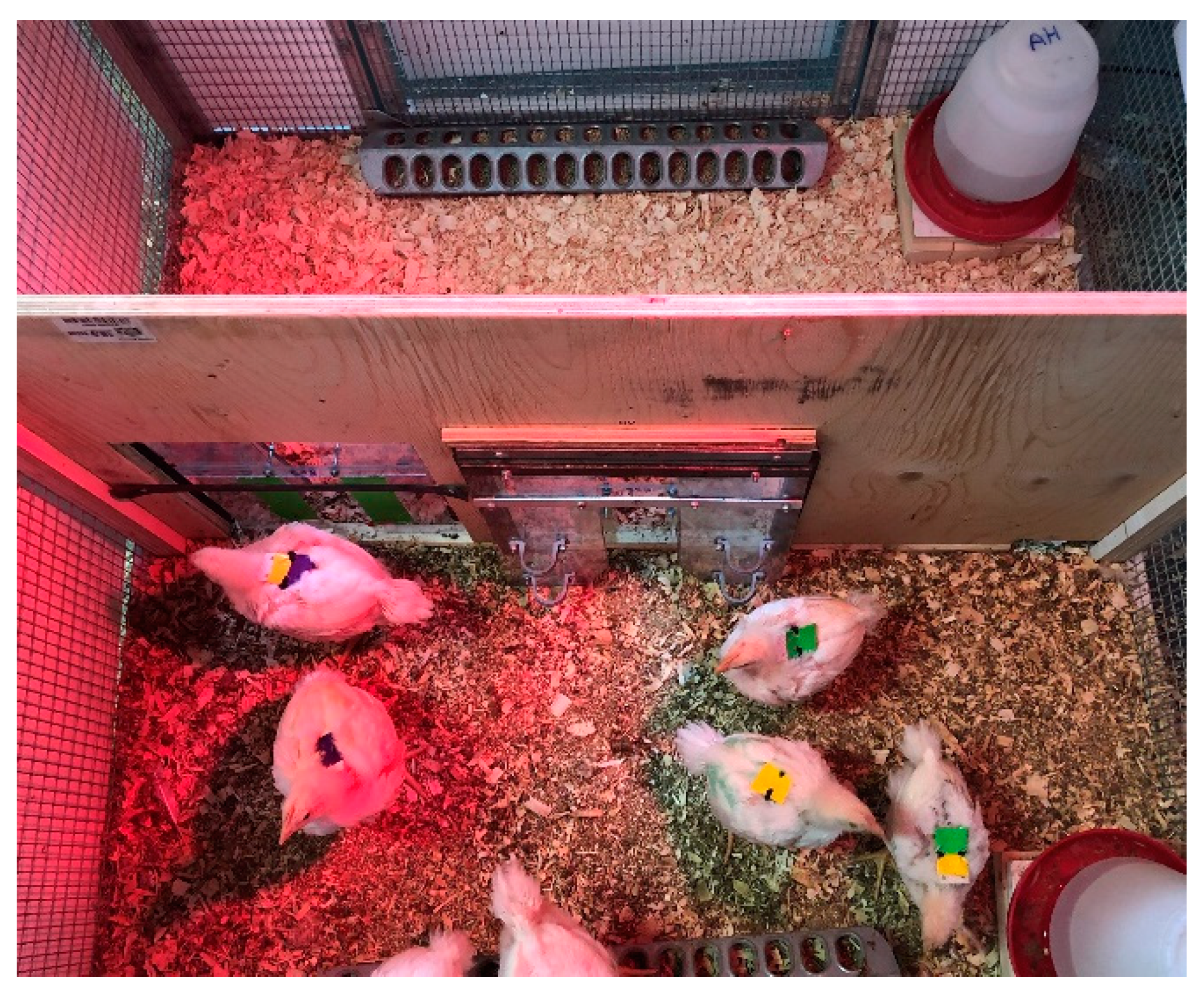

2.2. Housing, Feeding, and Management

2.3. Substrates

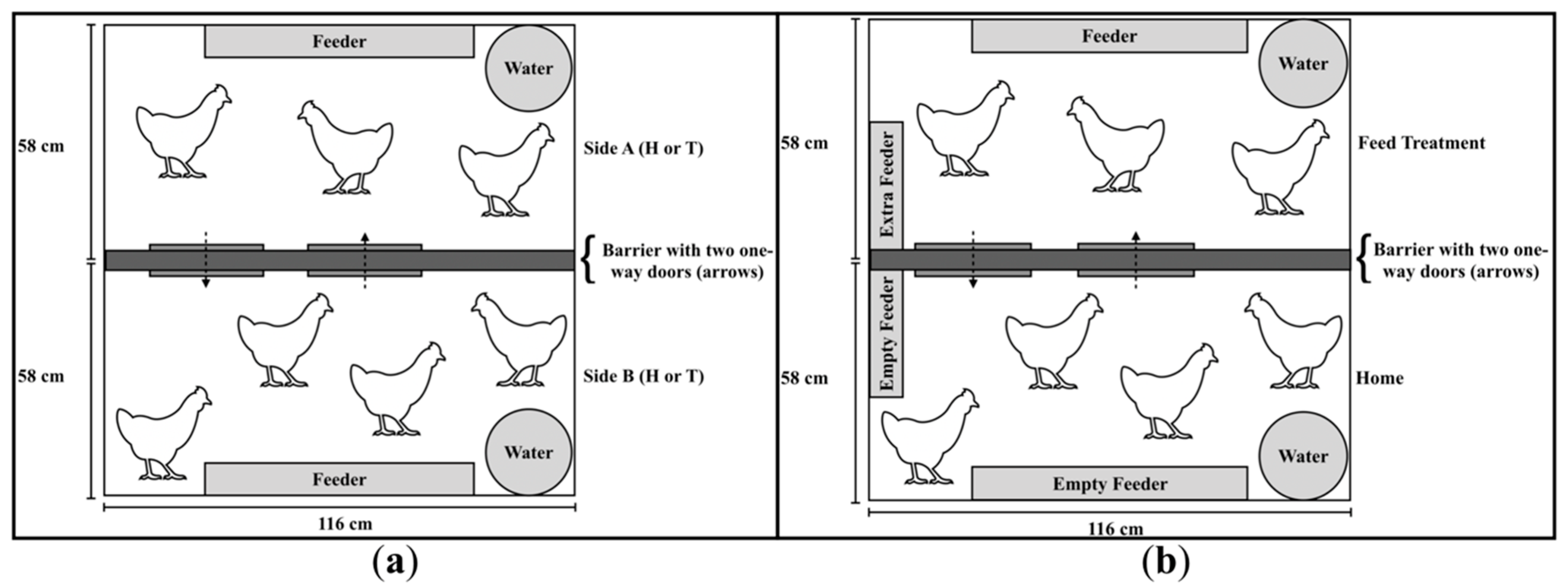

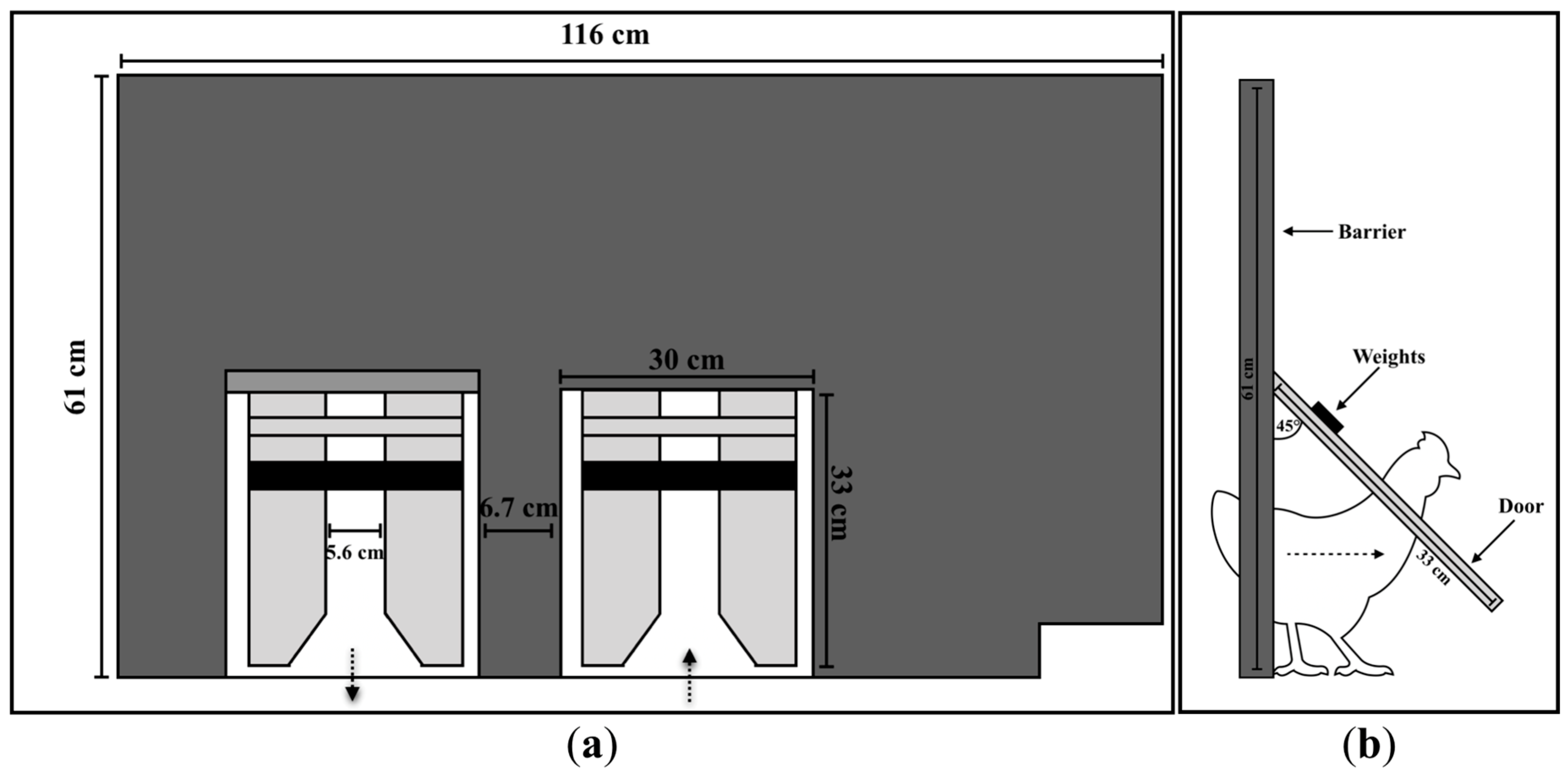

2.4. Push-Door Setup

2.5. Protocol

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

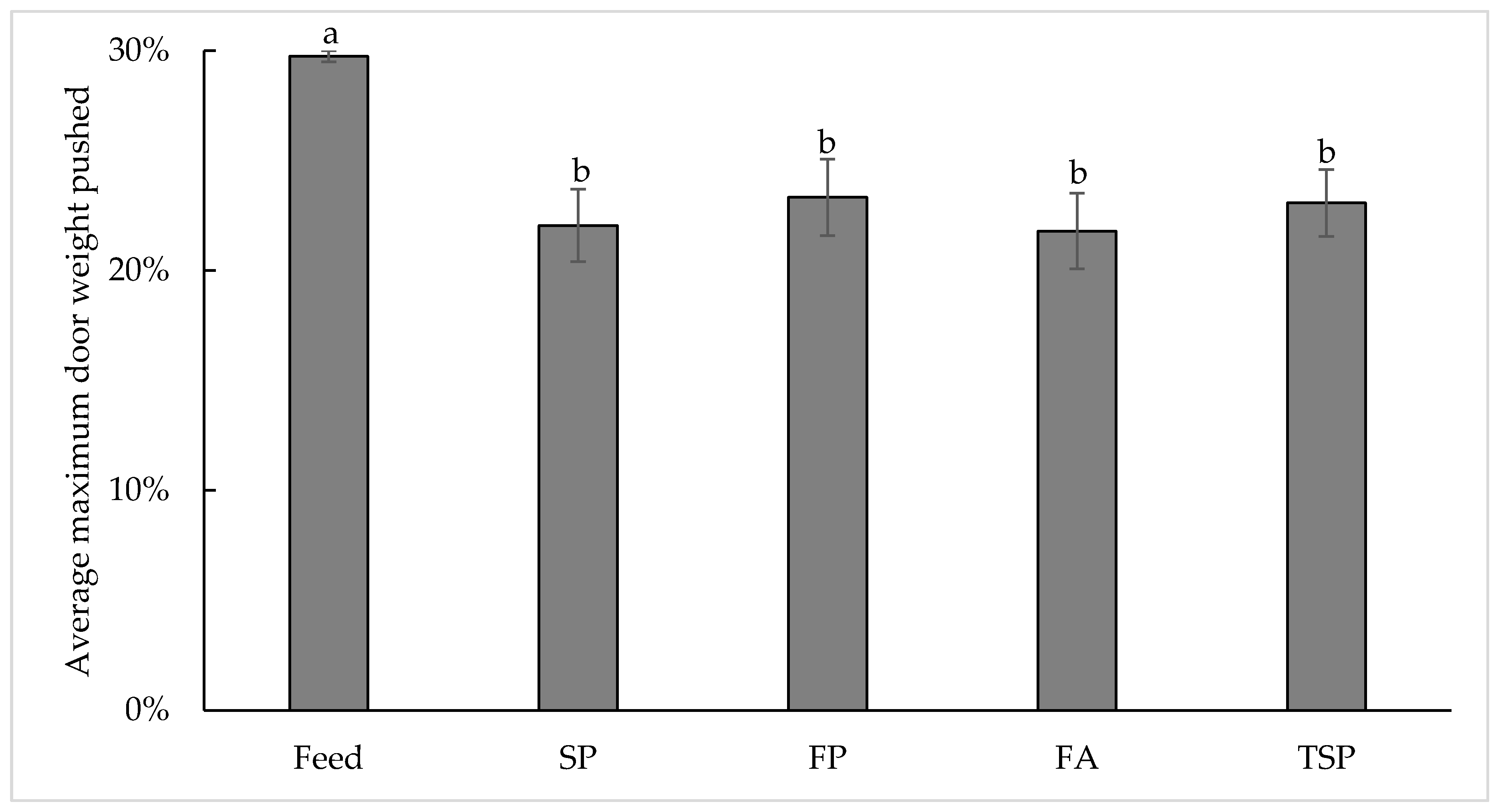

3.1. Motivational Index: Maximum Price Paid to Enter Treatment Compartment with Different Resources

3.2. The Effect of Increasing Cost on Visits to and Time Spent in the Treatment Compartment

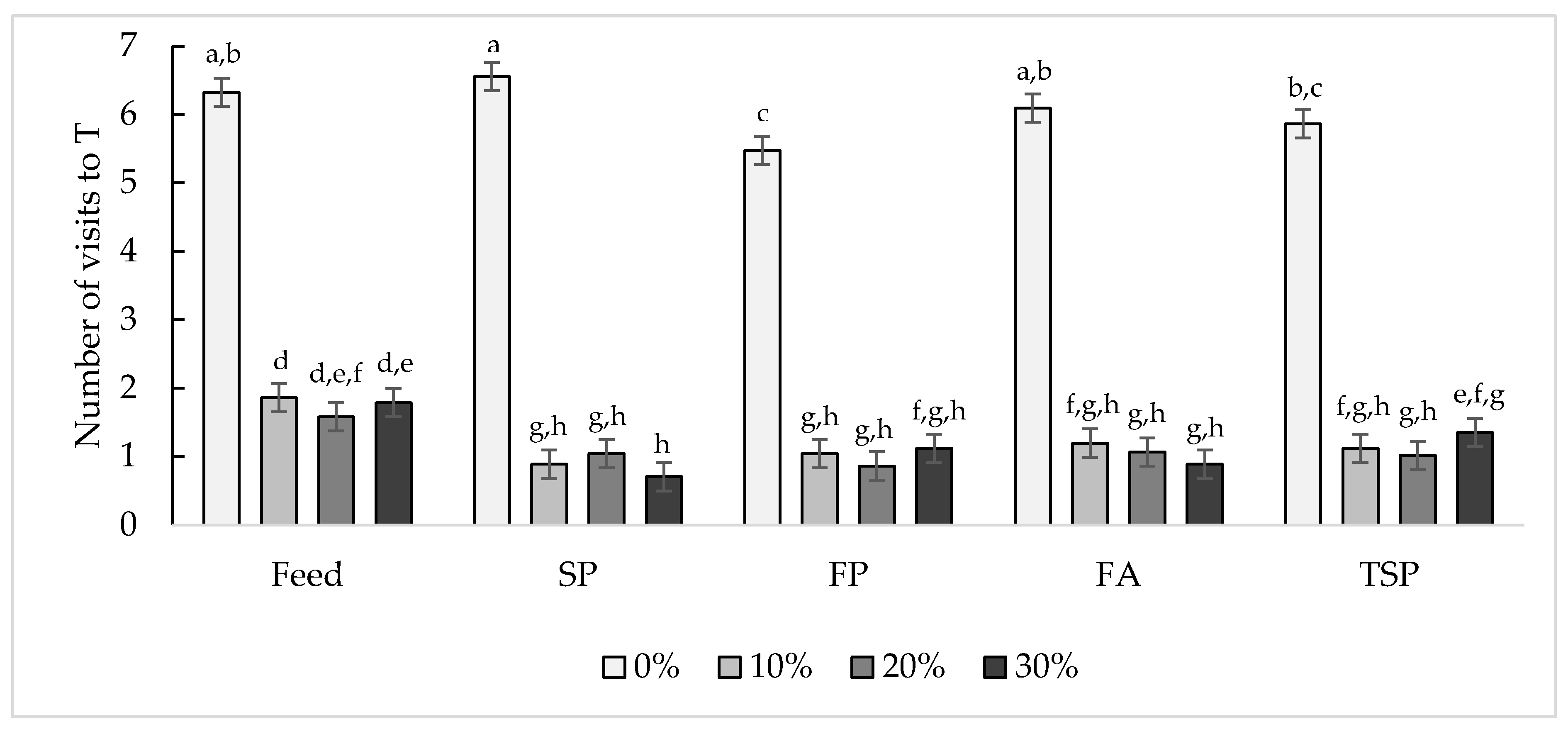

3.2.1. Number of Visits to the Treatment Compartment

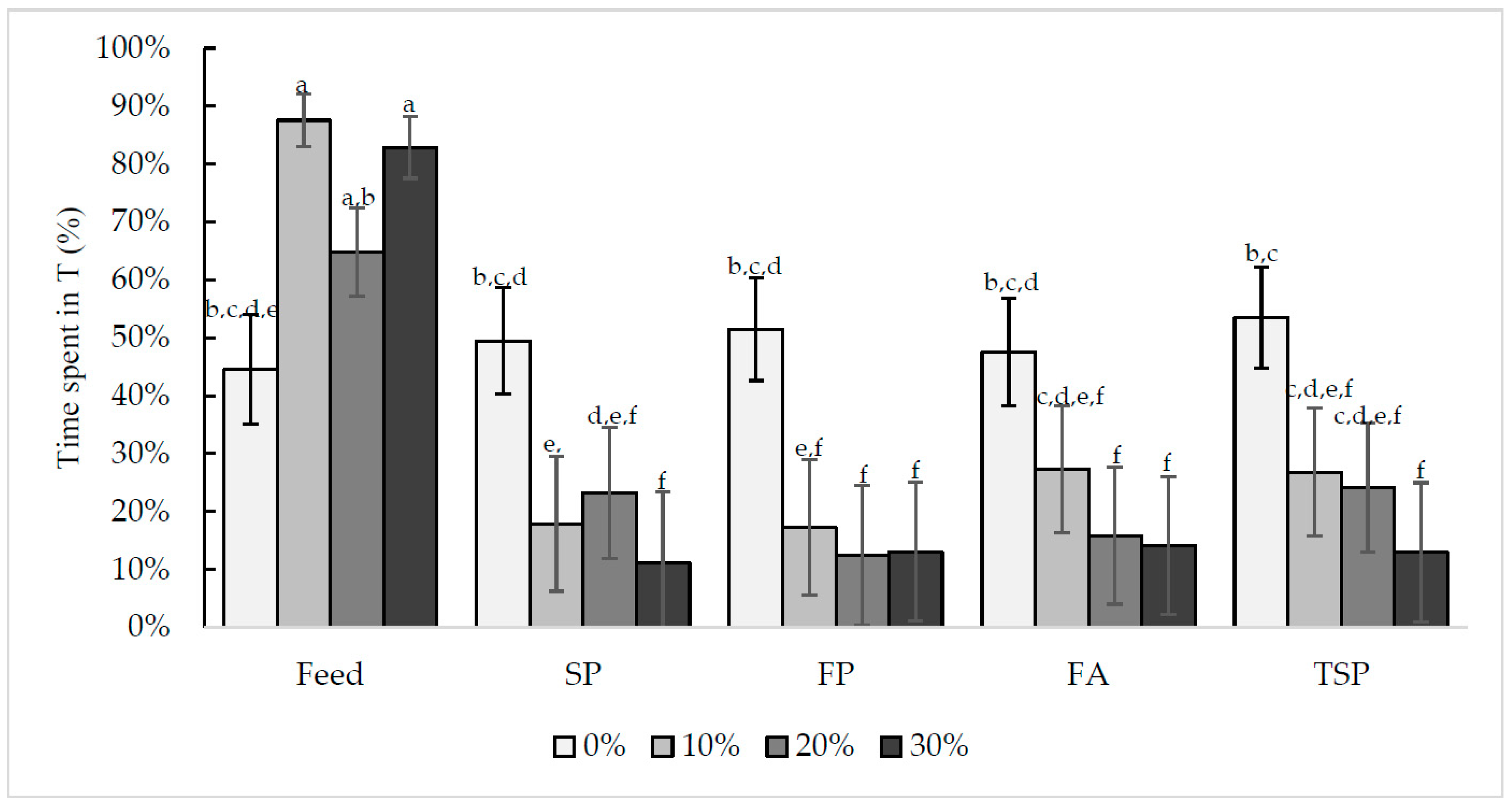

3.2.2. Time Spent in the Treatment Compartment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hart, A.G.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. Waste management in the leaf-cutting ant Atta colombica. Behav. Ecol. 2002, 13, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowska, I.J.; Franks, B.; El-Hinn, C.; Jorgensen, T.; Weary, D. Standard laboratory housing for mice restricts their ability to segregate space into clean and dirty areas. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, K.A. Red howling monkey use of specific defecation sites as a parasite avoidance strategy. Anim. Behav. 1997, 54, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Álamo, J.D.; Rubio, E.; Soler, J.J. Evolution of nestling faeces removal in avian phylogeny. Anim. Behav. 2017, 124, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, K.E.; Petit, L.J.; Petit, D.R. Fecal Sac Removal: Do the Pattern and Distance of Dispersal Affect the Chance of Nest Predation? Condor 1989, 91, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marten, G.; Donker, J. Selective Grazing Induced by Animal Excreta I. Evidence of Occurrence and Superficial Remedy. J. Dairy Sci. 1964, 47, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. Code of Practice for the Welfare of Meat Chickens and Meat Breeding Chickens; Department for Environment, Food, & Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Farm Animal Care Council. Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Hatching Eggs, Breeders, Chickens, and Turkeys; National Farm Animal Care Council: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard, K.; Skadhauge, E.; Lawson, L.G. The stress of not being able to perform dustbathing in laying hens. Physiol. Behav. 1997, 62, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, S.; Saraiva, C.; Stilwell, G. Feather conditions and clinical scores as indicators of broilers welfare at the slaughterhouse. Res. Veter Sci. 2016, 107, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagazaurtundua, A.; Warriss, P.D. Measurements of footpad dermatitis in broiler chickens at processing plants. Veter Rec. 2006, 158, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.M.; Anders, S.A.; Crowe, T.; Korver, D.R.; Bench, C.J. Practical assessment and management of foot pad dermatitis in commercial broiler chickens: A Field Study. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2017, 26, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, M.A. Welfare issues in turkey production. Adv. Poult. Welfare 2018, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, D.M.; Rowe, D.E.; Cathcart, T.C. High litter moisture content suppresses litter ammonia volatilization. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, R.T. Aerial pollutants and the health of poultry farmers. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 1993, 49, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, H.; Wathes, C. Ammonia and poultry welfare: A review. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2000, 56, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, G.H.; Schaumburg, I.; Sigsgaard, T.; Schlünssen, V. Non-malignant respiratory diseases and occupational exposure to wood dust. Part II. Dry wood industry. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2010, 17, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, G.H.; Schaumburg, I.; Sigsgaard, T.; Schlünssen, V. Non-malignant respiratory diseases and occupational exposure to wood dust. Part I. Fresh wood and mixed wood industry. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2010, 17, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shamssain, M.H. Pulmonary function and symptoms in workers exposed to wood dust. Thorax 1992, 47, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, M.; Suuronen, K.; Suomela, S.; Aalto-Korte, K. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by colophonium. Contact Dermat. 2018, 80, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estlander, T.; Jolanki, R.; Alanko, K.; Kanerva, L. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by wood dusts. Contact Dermat. 2001, 44, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törrönen, R.; Pelkonen, K.; Kärenlampi, S. Enzyme-inducing and cytotoxic effects of wood-based materials used as bedding for laboratory animals. Comparison by a cell culture study. Life Sci. 1989, 45, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelkonen, K.H.; Hänninen, O.O. Cytotoxicity and biotransformation inducing activity of rodent beddings: A global survey using the Hepa-1 assay. Toxicology 1997, 122, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathes, C.M.; Jones, J.; Kristensen, H.; Jones, E.K.M.; Webster, A.J.F. Aversion of pigs and domestic fowl to atmospheric ammonia. Trans. ASAE 2002, 45, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, B.B.; dos Santos, V.M.; Wood, D.; van Heyst, B.; Harlander-Matauschek, A. Laying hens behave differently in artificially and naturally sourced ammoniated environments. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 4151–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, B.B.; Boecker, I.; Kwon, I.Y.; Jeyachanthiran, L.; McBride, P.; Harlander-Matauschek, A. How does the presence of excreta affect the behavior of laying hens on scratch pads? Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Waldburg-Zeil, C.G.; van Staaveren, N.; Harlander-Matauschek, A. Do laying hens eat and forage in excreta from other hens? Anim. 2018, 13, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hörnicke, H.; Björnhag, G. Coprophagy and related strategies for digesta utilization. In Proceedings of the Digestive Physiology and Metabolism in Ruminants; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; pp. 707–730. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Hamilton Co. PLT®—Poultry Litter Treatment Product Data Sheet for Broilers; Jones-Hamilton Co.: Walbridge, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, B.O.; Black, A.J. The preference of domestic hens for different types of battery cage floor. Br. Poult. Sci. 1973, 14, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.S.; Paixão, S.J.; Restelatto, R.; Morello, G.M.; de Moura, D.J.; Possenti, J.C. Performance and preference of broiler chickens exposed to different lighting sources. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2013, 22, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.; Matthews, L.R. Preference and Motivation Testing. In Animal Welfare; Appleby, M.C., Hughes, B.O., Eds.; CAB International: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, S.; Keeling, L.J.; Tuyttens, F.A. Using motivation to feed as a way to assess the importance of space for broiler chickens. Anim. Behav. 2011, 81, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, I.; Keeling, L. The push-door for measuring motivation in hens: Laying hens are motivated to perch at night. Anim. Welfare 2002, 11, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, H.; Mason, G. Is out of sight out of mind? The effects of resource cues on motivation in mink, Mustela vison. Anim. Behav. 2003, 65, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Mason, G.J. The use of operant technology to measure behavioral priorities in captive animals. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2001, 33, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovland, A.L.; Mason, G.; Bøe, K.E.; Steinheim, G.; Bakken, M. Evaluation of the ‘maximum price paid’ as an index of motivational strength for farmed silver foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 100, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garmon, J. Managing the Ross 708 Parent Stock Female. Ross Tech. 2007, 5. Available online: http://cn.aviagen.com/assets/Tech_Center/Ross_Tech_Articles/RossTechManagingRoss708PSFemaleAug07.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Welfare Quality R Consortium. Welfare Quality® Assessment Protocol for Poultry; Welfare Quality® Consortium: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, M.S. Battery hens name their price: Consumer demand theory and the measurement of ethological ‘needs’. Anim. Behav. 1983, 31, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petherick, J.; Seawright, E.; Waddington, D. Influence of motivational state on choice of food or a dustbathing/foraging substrate by domestic hens. Behav. Process. 1993, 28, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokkers, E.A.; Koene, P. Motivation and ability to walk for a food reward in fast- and slow-growing broilers to 12 weeks of age. Behav. Process. 2004, 67, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokkers, E.A.; Koene, P. Eating behaviour, and preprandial and postprandial correlations in male broiler and layer chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2003, 44, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, S.; Gentle, M.; McCorquodale, C.; Bennett, D. The effect of morphology on walking ability in the modern broiler: A gait analysis study. Anim. Welfare 2003, 12, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- van Liere, D.; Kooijman, J.; Wiepkema, P. Dustbathing behaviour of laying hens as related to quality of dustbathing material. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1990, 26, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, I.C.; Wolthuis-Fillerup, M.; van Reenen, C.G. Strength of preference for dustbathing and foraging substrates in laying hens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 104, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; AIbentosa, M. SociaI space for Iaying hens. Welfare Lay. Hen 2004, 27, 191. [Google Scholar]

- Wood-Gush, D.; Vestergaard, K. The seeking of novelty and its relation to play. Anim. Behav. 1991, 42, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, M.R.P.; Garner, J.P.; Johnson, A.; Kirkden, R.D.; Richert, B.T.; Pajor, E.A. If You Knew What Was Good For You! The Value of Environmental Enrichments With Known Welfare Benefits Is Not Demonstrated by Sows Using Operant Techniques. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2012, 15, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawkins, M.; Layton, R. Breeding for better welfare: Genetic goals for broiler chickens and their parents. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C. How animals learn from each other. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 100, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petherick, J.C.; Duncan, I.J.H. Behaviour of young domestic fowl directed towards different substrates. Br. Poult. Sci. 1989, 30, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, S.J.; Garner, J.P.; Mench, J.A. Dustbathing by broiler chickens: A comparison of preference for four different substrates. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 87, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, B.; Urselmans, S.; Kjaer, J.B.; Schrader, L. Food, wood, or plastic as substrates for dustbathing and foraging in laying hens: A preference test. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinebretière, M.; Beyer, H.; Arnould, C.; Michel, V. The choice of litter material to promote pecking, scratching and dustbathing behaviours in laying hens housed in furnished cages. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 155, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moesta, A.; Knierim, U.; Briese, A.; Hartung, J. The effect of litter condition and depth on the suitability of wood shavings for dustbathing behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 115, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riber, A.B.; van de Weerd, H.; de Jong, I.C.; Steenfeldt, S. Review of environmental enrichment for broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwin, C.; Nicol, C. Reorganization of behaviour in laboratory mice, Mus musculus, with varying cost of access to resources. Anim. Behav. 1996, 51, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Mason, G.J. Increasing costs of access to resources cause re-scheduling of behaviour in American mink (Mustela vison): Implications for the assessment of behavioural priorities. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 66, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Hocking, P. Turkeys are equally susceptible to foot pad dermatitis from 1 to 10 weeks of age and foot pad scores were minimized when litter moisture was less than 30%. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Wathes, C.; Webster, A. Strength of motivation of broiler chickens to seek fresh air after exposure to atmospheric ammonia. Br. Poult. Sci. 2003, 44, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widowski, T.M.; Duncan, I.J. Working for a dustbath: Are hens increasing pleasure rather than reducing suffering? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 68, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, B. What do animals want? Anim. Welf. 2019, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Litter Type | Average Moisture (%) | Average pH | Average Nitrogen (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home compartment litter | 29.4 ± 19.93 | 6.4 ± 0.16 | 1.7 ± 0.29 |

| Soiled pine and spruce wood shavings (SP) | 29.9 ± 16.67 | 7.3 ± 0.23 | 1.7 ± 0.04 |

| SP treated with an ammonia reductant (TSP) | 20.0 ± 1.94 | 4.9 ± 2.08 | 1.8 ± 0.32 |

| Fresh pine and spruce wood shavings (FP) | 18.61 | 9.33 | 0.25 |

| Fresh aspen wood shavings (FA) | 5.57 | 5.26 | 0.34 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monckton, V.; van Staaveren, N.; Harlander-Matauschek, A. Broiler Chicks’ Motivation for Different Wood Beddings and Amounts of Soiling. Animals 2020, 10, 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10061039

Monckton V, van Staaveren N, Harlander-Matauschek A. Broiler Chicks’ Motivation for Different Wood Beddings and Amounts of Soiling. Animals. 2020; 10(6):1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10061039

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonckton, Valerie, Nienke van Staaveren, and Alexandra Harlander-Matauschek. 2020. "Broiler Chicks’ Motivation for Different Wood Beddings and Amounts of Soiling" Animals 10, no. 6: 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10061039

APA StyleMonckton, V., van Staaveren, N., & Harlander-Matauschek, A. (2020). Broiler Chicks’ Motivation for Different Wood Beddings and Amounts of Soiling. Animals, 10(6), 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10061039