Abstract

The scientific knowledge already attained regarding the way severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infects human cells and the clinical manifestations and consequences for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients, especially the most severe cases, brought gut microbiota into the discussion. It has been suggested that intestinal microflora composition plays a role in this disease because of the following: (i) its relevance to an efficient immune system response; (ii) the fact that 5–10% of the patients present gastrointestinal symptoms; and (iii) because it is modulated by intestinal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (which is the virus receptor). In addition, it is known that the most severely affected patients (those who stay longer in hospital, who require intensive care, and who eventually die) are older people with pre-existing cardiovascular, metabolic, renal, and pulmonary diseases, the same people in which the prevalence of gut microflora dysbiosis is higher. The COVID-19 patients presenting poor outcomes are also those in which the immune system’s hyperresponsiveness and a severe inflammatory condition (collectively referred as “cytokine storm”) are particularly evident, and have been associated with impaired microbiota phenotype. In this article, we present the evidence existing thus far that may suggest an association between intestinal microbiota composition and the susceptibility of some patients to progress to severe stages of the disease.

1. The “Gut Microbiota Hypothesis” in Poor Outcomes of COVID-19 Patients

Gut microbiota is a complex and dynamic ecosystem that comprises trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria and virus, with which the host maintains a beneficial symbiotic relationship [1,2,3]. This microbe community is extremely important in maintaining the host’s homeostasis, influencing several of its physiological functions, such as energy production, maintenance of the intestinal integrity, protection against pathogenic organisms, and regulation of host’s immunity [2,3,4,5,6]. However, these homeostasis mechanisms can become compromised as a consequence of alterations in the normal gut microbiota composition or functions, a condition known as dysbiosis [7]. Gut microbiota is influenced by different factors, both environmental and intrinsic to the host [3], including geographic localization, diet and nutrition, aging, antibiotics’ intake, stress, as well as by disease states, among other factors [3,6,8,9,10]. Changes in intestinal microbiota composition towards dysbiosis will affect and compromise the host’s functions in which it is involved, including immune system response against infections. On the other hand, there is evidence that infections, including bacterial or viral, can cause alterations in the intestinal flora, predisposing the host to secondary infections and aggravating its clinical status [2,11,12,13].

The year 2020 will be remembered in history for the emergence of millions of infections caused by a new virus from the Coronavirus family, named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). This infection, designated by the World Health Organization (WHO) as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), has been disseminating all over the world, reaching pandemic proportions. In about a year, the infection has already affected more than 60 million people from almost all countries and caused more than 1.5 million deaths, as of December 2020.

SARS-CoV-2 infection starts by the binding of virus spike surface glycoprotein (S) to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors present in many human cells, which is then cleaved by host proteases (e.g., cathepsin, TMPRRS2, or furin), thus allowing virus internalization in the host cells [14]. The most typical symptoms, which usually appear in a few days after viral exposure, are fever, cough, fatigue, muscle or body aches, and shortness of breath, further evolving to pneumonia. In more severe cases, patients present respiratory, hepatic, gastrointestinal, and neurological complications, which require hospitalization and eventually progress to multi-organ dysfunction and death [15]. COVID-19 severity and mortality rate are considerably higher in elderly patients, particularly those with pre-existing comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, or pulmonary conditions, among other chronic diseases [16,17,18].

Additionally, different studies have demonstrated that 5–10% of COVID-19 patients present digestive symptoms, such as abdominal pain, vomits, and diarrhea, as well as intestinal inflammation [19,20,21,22]. These data suggest that the gastrointestinal tract might be a location of viral activity and replication, which agrees with the high expression of ACE2 in the intestinal epithelium [23,24,25,26]. ACE2 is recognized as an important regulator of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) by counteracting the negative actions mediated by Angiotensin II signaling via its type 1 receptor [27]. Thus, cleavage of ACE2 after SARS-CoV-2 infection might contribute to explaining the poor outcomes observed in COVID-19 patients with pre-existing comorbidities usually associated with RAS overactivity, such as respiratory, cardiac, and renal disorders, as well as diabetes [27].

ACE2 also exerts non-RAS-related roles linked with the transport of neutral amino acids across the gut epithelial cells, with a putative impact on gut homeostasis and microbiota composition [28]. In fact, ACE2 acts as a chaperone for membrane trafficking of the amino acid transporter B0AT1, which mediates the uptake of neutral amino acids, namely tryptophan (Trp), into intestinal cells. A link between ACE2-mediated amino acid transport and gut flora composition has been suggested, in such a way that impaired ACE2 expression or function are potentially promoters of gut microbiota dysbiosis [28,29]. These pieces of evidence are in line with the gastrointestinal symptoms that have been reported in a non-negligible percentage of people with SARS-CoV-2, suggesting an impact on the gastrointestinal-enteric system [30]. In fact, several reports point to alterations in gut microflora composition in COVID-19 patients, with their microbiota being characterized by a decreased bacterial diversity, enrichment in opportunistic pathogens, and loss of beneficial symbionts [31,32,33,34,35]. Thus, it has been suggested that ACE2 shedding promoted by SARS-CoV-2 infection might contribute to intestinal microflora dysbiosis, thus eventually helping to explain the poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients with pre-existing comorbidities [36]. The infected patients with a higher frequency of intensive care unit (ICU) admission (disease severity) and increased mortality rate are typically elderly people with pre-existing cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal disorders, including hypertension, heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease, among others—conditions that have been associated with gut microbiota alterations [8,37,38].

In line with the previous major coronavirus outbreaks in humans (namely SARS-CoV and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV)) [39], the more severe cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been associated with a hyperresponse of the immune system, featured by an exacerbated systemic inflammatory response and the massive release of cytokines, collectively described as a “cytokine storm” [40]. The resulting multi-organ failure fueled by a self-sustaining loop of ongoing age-related immunosenescence and inflammaging can additionally contribute to the poor outcomes in elderly patients with chronic comorbidities [15,41,42].

Among other relevant metabolic and structural protective functions, gut microbiota plays a major role in the host immune system education and ability to respond to insults, including to infections [1]. Disruption of gut microbiota influences the host’s immune response, worsening SARS-CoV-2-induced injury, owing to an excessive reactivity of the immune system and a strong inflammatory state [43,44,45]. In addition, different lines of evidence show that respiratory viral infections may originate alterations in the intestinal microbiome composition, which predispose patients to secondary infections and aggravate their clinical status [11,12,43,44,45]. We and others have recently proposed that the triad of gut microbiota dysbiosis, immune hyperresponse, and inflammation could eventually explain why some COVID-19 patients are more resilient, while others are more fragile when infected with SARS-CoV-2, recovering faster or progressing to more severe clinical condition, respectively [25,46,47,48,49]. As the ongoing studies reveal new evidence, this hypothesis has been gaining more and more consistency, in such a way that gut microbiota composition might eventually be viewed as a putative predictor of COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. In the next paragraphs, we report the data already known that may contribute to validating this possibility.

2. What Is the Evidence So Far that Links Gut Microbiota Composition to COVID-19 Severity?

Gut microbiota is crucial to the process of development and function of the immune system [1,50,51,52], as it modulates immune cells towards anti- or pro-inflammatory responses. Different studies have described significant changes regarding the innate and adaptive immune systems in COVID-19 patients [53,54,55,56]. The cytokine storm, in particular, clearly reflects an uncontrolled dysregulation of the host’s immune function. Several pieces of evidence point to the occurrence of lymphocytopenia in individuals with SARS-CoV-2 [57,58,59,60,61]. In a study involving 452 severe COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, a significant decrease in the number of T lymphocytes, including helper and suppressor T cells, was observed [62]. Particularly, among helper T cells, the researchers reported a decrease in regulatory and memory T cells counts. However, naïve T cells percentage was increased in COVID-19 patients relative to healthy individuals, which might contribute to hyperinflammation events, as there is an imbalance between the activity of naïve T cells and that of regulatory and memory T cells [62]. Furthermore, a reduced number of memory T cells might be implicated in COVID-19 relapses, which are particularly evident when recurrences in recovered patients arise [62].

Kalfaoglu et al., by analyzing CD4+ T lymphocytes’ transcriptomes from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) belonging to moderate and severe COVID-19 patients, observed that SARS-CoV-2 is capable of inducing activation and differentiation processes in these cells, accelerating both their activation and death [55]. These authors proposed a hypothesis stating that the abnormally activated CD4+ T cells might be able to promote the viral entry through Furin production in critically ill patients. When compared with moderate patients, CD4+ T cells from severe patients present an increased expression of the genes fos, fosb, and jun; of the activation marker MKI67; of Th2-related genes maf and il4r; and of chemokines CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL7, CCL8, and CXCL8. These results suggest that CD4+ T cells in severe COVID-19 patients’ lungs are highly activated and recruit other immune cells. In contrast, these patients display decreased expression of interferon-induced genes, such as ifit1, ifit2, ifit3, and ifim1, as well as genes associated with interferon downstream pathways, suggesting that interferons might be suppressed in severe COVID-19 cases [55]. In addition, Huang et al. discovered that the plasmatic concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-1ra, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, basic FGF, GM-CSF, G-CSF, VEGF, IP-10, MCP-1, IFN-γ, IFN-α, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β were higher in COVID-19 patients present in ICU, as well as non-ICU patients, when compared with healthy individuals [63]. A possible explanation for the potential contradictory evidence of a decrease in the expression of interferon-induced genes’ and interferon downstream pathways and increased plasmatic IFNs levels might be associated with the fact that plasma levels are defined by the IFNs’ input from several tissues, including the gut [64]. This study raises the premise that the cytokine storm observed in COVID-19 cases might be correlated with disease severity, as IL-2, IL-7, IL-10, G-CSF, MCP-1, IP-10, TNF-α, and MIP-1α levels were higher in ICU patients compared with non-ICU ones [63]. Moreover, a study evaluating a cohort of 44 hospitalized COVID-19 patients reported the existence of higher median fecal levels of IL-8 and lower levels of fecal IL-10 in COVID-19 patients compared with control individuals [65]. Furthermore, IL-23 fecal levels were increased in severe patients, suggesting the involvement of the GI tract in the SARS-CoV-2 infection in an immunological manner [65]. More severe cases were also associated with higher serum levels of IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), D-dimer, ferritin, and procalcitonin [65]. Furthermore, a study performed by Li et al. allowed to observe that the lower the counts on admission of total T cell, CD4+ T cell, and CD8+ T cell, the more serious the disease and the worse the prognosis of the patients [66]. A recent study also showed that lymphopenia and an increase in cytokine levels were significantly correlated with disease severity, with the IL-2R/lymphocyte ration being a potential biomarker for COVID-19 disease severity and progression identification [67].

Several studies have already demonstrated that, when compared with healthy individuals, COVID-19 patients present a significantly reduced bacterial diversity [31,68]; higher abundancy of opportunistic bacteria such as Streptococcus, Rothia, Veilonella, and Actinomyces [31,34,35]; and decreased levels of benefic symbionts, including Agathobacter, Fusicatenibacter, Roseburia, and Ruminococcaceae UCG-013 [31,35]. A study performed by Zuo et al. reported that most patients’ gut microbiota composition alterations persisted even after viral clearance, suggesting that the infection or/and hospitalization might be associated with a long-lasting adverse effect regarding the composition of intestinal microflora community [35], which might be potentially associated with recovery delays. Remarkably, the existence of a correlation between the COVID-19 severity grade and the basal fecal microbiome has been established [35,68]. In the study performed by Zuo et al., twenty-three bacterial taxa showed a significant positive correlation with disease severity; with the main bacteria presenting a positive association with COVID-19 severity belong to the filo Firmicutes and the genus Coprobacillus, as well as the Clostridium ramosum and Clostridium hathewayi species [35]. Interestingly, the fact that Firmicutes presented this positive association with disease severity is in accordance with evidence showing that these bacteria possess a specific role in regulating ACE2 expression in the murine gut [69]. On the other hand, two beneficial bacterial species—Alistipes ondedonkii (important for the maintenance of intestinal homeostais) and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (anti-inflammatory properties detainer)—showed a negative correlation with COVID-19 severity [35].

It is now acknowledged that gut microbiota is responsible for regulating several hosts’ physiological functions [70,71,72]. Particularly, numerous studies have reported that intestinal microflora affects lung health through a bidirectional pathway designated as the “gut–lung axis” [73,74,75]. One of the main complications associated with COVID-19 is acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [76,77], in which microbiota composition and function might play an important part. An enrichment of lung microbiota with intestinal Bacteroides species is observed in many COVID-19 cases [78], an event linked to increased plasmatic inflammatory markers levels [78]. Another study reported an increase in Enterobacteiaceae and Lachnospiraceae levels in severely ill patients with ARDS, when compared with patients that did not present this condition [32,79]. These results suggest that the microbiota could be seen as potential marker to predict ARDS and other possible scenarios associated with COVID-19 pathology.

Therefore, gut microbiota might provide information about the individual susceptibility to COVID-19. Gou et al. recently reported that changes in the normal composition and function of intestinal microbiota might predispose healthy individuals to an atypical inflammatory response, such as the one observed in COVID-19 cases [80]. Additionally, a study performed in Wuhan, China confirmed the existence of this relationship between gut microflora composition and the predisposition of healthy individuals to SARS-CoV-2 infection [78]. The researchers observed that individuals that display increased numbers of Lactobacillus present higher levels of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, and generally a more favorable prognosis. In contrast, individuals displaying higher numbers of pro-inflammatory bacterial species, such as Klebsiella, Streptococcus, and Ruminococcus gnavus, showed increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as more pronounced disease severity [78]. Furthermore, through the evaluation of the metabolomic and proteomic profile of COVID-19 patients’ serum, a study performed by Shen et al. revealed specific alterations in severely ill patients [33]. In fact, increased serum concentrations of inflammatory markers, such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP, were associated with a higher prognostic risk score (PRS) in patients over 58 years old [33]. By investigating the potential role of gut microbiota on the susceptibility of healthy individuals to COVID-19, the investigators demonstrated that the observed alterations regarding blood proteomic markers would be preceded by intestinal microflora changes, suggesting a potential causal relationship in the case of older patients [33] Specifically, the genus Bacteroides and Streptococcus, as well as the order Clostridiales, showed a negative correlation with the majority of the tested cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, TNF-α, and IFN-γ), while the genus Lactobacillus, Ruminococcus, and Blautia displayed positive associations with the referred cytokines [33]. Another study has reported that abundant bacteria in COVID-19 patients, including Rothia, Streptococcus, Veilonella, and Actinomyces, are positively correlated with high levels of CRP and D-dimer, once more evidencing the influence of gut microbiota composition in the host’s inflammatory profile [31]. However, no significant alterations were observed in gut microbiota composition between patients with different disease severity stages [65]. These results suggest that, in this complex scenario of interactions between different systems (namely intestinal microbiota–immune system–inflammatory response), there may be additional factors playing a relevant role for disease severity. On the other hand, it also suggests that other elements able to shape microbiota should be carefully considered, including age; comorbidities; and especially the impact of drugs, particularly antibiotics, as highlighted in the study of Britton et al. [65].

Collectively, there is evidence suggesting that microbiota characteristics and related metabolites should be more profoundly investigated as potential prediction markers of individual susceptibility of COVID-19 patients to develop a more severe phenotype. Table 1 summarizes the major findings regarding gut microbiota, inflammation, and immune system changes in COVID-19 patients, and the suggested associations with disease severity. However, only the publication of more results from the different clinical trials related to gut microbiota with patients affected with distinct levels of severity could open up the possibility to clarify the existence of causality in this association.

Table 1.

Major findings regarding changes on gut microbiota, inflammation, and immune system markers in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients, and the suggested associations with disease severity.

3. Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

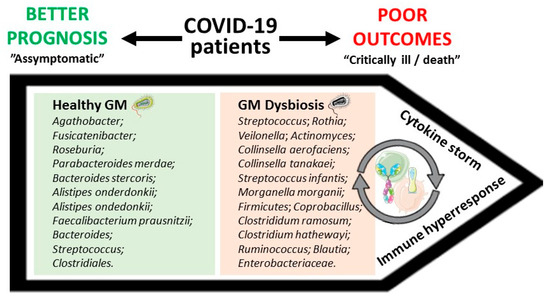

COVID-19 patients display immune response deregulation and increased levels of specific inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, with these alterations being particularly intense in severe patients, in a condition often referred as cytokine storm [32,33,53,55]. Other studies also report that the blood lymphocyte percentage might reflect disease progression and severity [59], as well as the number of leukocytes and B and natural killer (NK) cells [81,82]. Gut microbiota plays major functions in the host, including immune system education and strengthening [1,51,52]. Several studies have reported major impairment of innate and adaptive immune systems in COVID-19 patients [53,54,55,56], accompanied by changes in gut microbiota composition [31,32,33,34,35]. It has been suggested that intestinal microflora composition could be correlated with the predisposition of healthy individuals to COVID-19 and with disease severity [31,33,34,35,78]. In particular, some data suggest that certain microbiota characteristics allow the prediction of the occurrence of ARDS and other disease-associated scenarios [32,78]. Moreover, COVID-19 patients’ microbial composition correlates with altered levels of inflammatory markers when compared with healthy individuals [31,33,78], reinforcing the potential relevance for the disease. These data have been leading researchers to refer to gut microbiota composition, inflammatory markers’ levels, and immune cells’ number and activity as potential predictors of susceptibility of healthy individuals to COVID-19, as well as of disease severity (Figure 1), as these parameters differ significantly between healthy and infected individuals, as well as between moderate and severe COVID-19 patients [31,32,33,35,59,78,80]. However, with the current knowledge, it is impossible to ensure a causal relationship, which remains an open hypothesis that deserves to be better dissected.

Figure 1.

Putative correlation between Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) clinical outcomes and gut microbiota (GM) composition. Green and red squares display some examples of bacteria encompassing better or poor COVID-19 outcomes, respectively.

The evidence collected thus far suggests that modifications in the characteristics of the intestinal microbial community and the relationship it establishes with the immune system, which leads to changes in inflammatory markers’ levels and in the number and function of several immune cells, should be more profoundly investigated as potential predictors of individual susceptibility to a more severe COVID-19 phenotype. Additionally, these parameters might be used to support the implementation of therapeutic measures to prevent disease evolution in populations with higher susceptibility. Critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation who were given probiotics, specifically Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, live Bacillus subtilis, and Enterococcus faecalis, presented improvement of pneumonia when compared with placebo, in two randomized controlled trials [83,84]. However, the efficacy of probiotics use in COVID-19 patients remains to be proved and the issue is under debate [85,86], deserving more attention by the scientific-medical community.

Author Contributions

C.F. wrote the first draft, which was revised and completed by S.D.V. and F.R., who wrote other parts. S.D.V. drew the figure. All the authors (C.F., S.D.V., and F.R.) significantly contributed to the writing and have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) & Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (MCTES) funds; by Centro Portugal Regional Coordination and Development Commission (CCDR-C)/CENTRO2020/Portugal2020 funds; by European Regional Development Fund (FEDER); and by Programa Operacional Factores de Competitividade COMPETE2020 funds: UIDP/04539/2020 (CIBB); PTDC/SAU-NUT/31712/2017, POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007440, POCI-01-0145-FEDER-031712, and CENTRO-01-0145-FEDER-000012-HealthyAging2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Ma, W.T.; Pang, M.; Fan, Q.L.; Hua, J.L. The Commensal Microbiota and Viral Infection: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinane, C.M.; Cotter, P.D. Role of the gut microbiota in health and chronic gastrointestinal disease: Understanding a hidden metabolic organ. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2013, 6, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Cabral, C.; Kumar, R.; Ganguly, R.; Rana, H.K.; Gupta, A.; Lauro, M.R.; Carbone, C.; Reis, F.; Pandey, A.K. Beneficial Effects of Dietary Polyphenols on Gut Microbiota and Strategies to Improve Delivery Efficiency. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yao, M.; Lv, L.; Ling, Z.; Li, L. The Human Microbiota in Health and Disease. Engineering 2017, 3, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carding, S.; Verbeke, K.; Vipond, D.T.; Corfe, B.M.; Owen, L.J. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 26191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Viana, S.D.; Nunes, S.; Reis, F. Diabetic gut microbiota dysbiosis as an inflammaging and immunosenescence condition that fosters progression of retinopathy and nephropathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1876–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Yang, H. Factors affecting the composition of the gut microbiota, and its modulation. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Ramos, S.; Lopez-Contreras, B.E.; Villarruel-Vazquez, R.; Ocampo-Medina, E.; Macias-Kauffer, L.; Martinez-Medina, J.N.; Villamil-Ramirez, H.; León-Mimila, P.; Del Rio-Navarro, B.E.; Ibarra-Gonzalez, I.; et al. Environmental and intrinsic factors shaping gut microbiota composition and diversity and its relation to metabolic health in children and early adolescents: A population-based study. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 900–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, H.T.; Higham, S.L.; Moffatt, M.F.; Cox, M.J.; Tregoning, J.S. Respiratory Viral Infection Alters the Gut Microbiota by Inducing Inappetence. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanada, S.; Pirzadeh, M.; Carver, K.Y.; Deng, J.C. Respiratory Viral Infection-Induced Microbiome Alterations and Secondary Bacterial Pneumonia. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Hensley, C.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Ramesh, A.K.; Zhou, P. Microbiota in viral infection and disease in humans and farm animals. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 171, 15–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Krüger, N.; Müller, M.; Drosten, C.; Pöhlmann, S. The novel coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) uses the SARS-coronavirus receptor ACE2 and the cellular protease TMPRSS2 for entry into target cells. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zuo, Z.; Kang, S.; Jiang, L.; Luo, X.; Xia, Z.; Liu, J.; Xiao, X.; Ye, M.; Deng, M. Multi-organ Dysfunction in Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 874–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID, Team CDC, and Response Team. Severe Outcomes Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-United States, February 12-March 16, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncon, L.; Zuin, M.; Rigatelli, G.; Zuliani, G. Diabetic patients with COVID-19 infection are at higher risk of ICU admission and poor short-term outcome. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 127, 104354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siordia, J.A., Jr. Epidemiology and clinical features of COVID-19: A review of current literature. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 127, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Cai, G.; Chen, F.; Christiani, D.C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M. Multiomics Evaluation of Gastrointestinal and Other Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 2298–2301.e2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lian, J.S.; Hu, J.H.; Gao, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.M.; Hao, S.R.; Jia, H.Y.; Cai, H.; Zhang, X.L.; et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut 2020, 69, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villapol, S. Gastrointestinal symptoms associated with COVID-19: Impact on the gut microbiome. Transl. Res. 2020, 226, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Tu, L. Implications of gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 629–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, T.P.; Lubel, J.S.; Garg, M. Lessons From COVID-19, ACE2, and Intestinal Inflammation: Could a Virus Trigger Chronic Intestinal Inflammation? Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 19, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, S.; Gu, J.W.; Li, X.L.; Song, H.J.; Du, F.; Wang, G.; Zhong, C.Q.; Wang, X.Y.; et al. Digestive system involvement of novel coronavirus infection: Prevention and control infection from a gastroenterology perspective. J. Dig. Dis. 2020, 21, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninger, J.M.; Grant, M.B.; Sung, J.J.Y. The Role of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 in Modulating Gut Microbiota, Intestinal Inflammation, and Coronavirus Infection. Gastroenterology 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chu, M.; Zhong, F.; Tan, X.; Tang, G.; Mai, J.; Lai, N.; Guan, C.; Liang, Y.; Liao, G. Digestive symptoms of COVID-19 and expression of ACE2 in digestive tract organs. Cell Death Discov. 2020, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuba, K.; Imai, Y.; Penninger, J.M. Multiple functions of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its relevance in cardiovascular diseases. Circ. J. 2013, 77, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlot, T.; Penninger, J.M. ACE2—From the renin–angiotensin system to gut microbiota and malnutrition. Microbes Infect. 2013, 15, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Perlot, T.; Rehman, A.; Trichereau, J.; Ishiguro, H.; Paolino, M.; Sigl, V.; Hanada, T.; Hanada, R.; Lipinski, S.; et al. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature 2012, 487, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotfis, K.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K. COVID-19: Gastrointestinal symptoms and potential sources of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2020, 52, 171–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Gao, H.; Lv, L.; Guo, F.; Zhang, X.; Luo, R.; Huang, C.; et al. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Patients with COVID-19 or H1N1 Influenza. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Y. Main Clinical Features of COVID-19 and Potential Prognostic and Therapeutic Value of the Microbiota in SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, B.; Yi, X.; Sun, Y.; Bi, X.; Du, J.; Zhang, C.; Quan, S.; Zhang, F.; Sun, R.; Qian, L.; et al. Proteomic and Metabolomic Characterization of COVID-19 Patient Sera. Cell 2020, 182, 59–72.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.; Tso, E.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Chen, Z.; Boon, S.; Chan, F.K.L.; Chan, P.; et al. Depicting SARS-CoV-2 faecal viral activity in association with gut microbiota composition in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2020, gutjnl-2020-322294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.C.Y.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Li, A.Y.L.; Zhan, H.; Wan, Y.; Chung, A.C.K.; Cheung, C.P.; Chen, N.; et al. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 944–955.e948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, S.D.; Nunes, S.; Reis, F. ACE2 imbalance as a key player for the poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients with age-related comorbidities-Role of gut microbiota dysbiosis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 62, 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busnelli, M.; Manzini, S.; Chiesa, G. The Gut Microbiota Affects Host Pathophysiology as an Endocrine Organ: A Focus on Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2019, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Rodriguez, E.; Egea-Zorrilla, A.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Aragón-Vela, J.; Muñoz-Quezada, S.; Tercedor-Sánchez, L.; Abadia-Molina, F. The Gut Microbiota and Its Implication in the Development of Atherosclerosis and Related Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Channappanavar, R.; Perlman, S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: Causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Xu, Z.; Ji, J.; Wen, C. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: The Current Evidence and Treatment Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuellen, G.; Liesenfeld, O.; Kowald, A.; Barrantes, I.; Bastian, M.; Simm, A.; Jansen, L.; Tietz-Latza, A.; Quandt, D.; Franceschi, C.; et al. The preventive strategy for pandemics in the elderly is to collect in advance samples & data to counteract chronic inflammation (inflammaging). Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 62, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojyo, S.; Uchida, M.; Tanaka, K.; Hasebe, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Murakami, M.; Hirano, T. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm. Regen. 2020, 40, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. Nutrition, immunity and COVID-19. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2020, 3, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, V.; Ditu, L.-M.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Gheorghe, I.; Curutiu, C.; Holban, A.M.; Picu, A.; Petcu, L.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Aspects of Gut Microbiota and Immune System Interactions in Infectious Diseases, Immunopathology, and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, M.; Smeekens, S.P.; Vlamakis, H.; Jaeger, M.; Oosting, M.; Franzosa, E.A.; Ter Horst, R.; Jansen, T.; Jacobs, L.; Bonder, M.J.; et al. Linking the Human Gut Microbiome to Inflammatory Cytokine Production Capacity. Cell 2016, 167, 1125–1136.e1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.; Viana, S.D.; Reis, F. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis-Immune Hyperresponse-Inflammation Triad in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact of Pharmacological and Nutraceutical Approaches. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Vitale, E.; Makarewicz, W. COVID-19-gastrointestinal and gut microbiota-related aspects. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 10853–10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaimat, A.N.; Aolymat, I.; Al-Holy, M.; Ayyash, M.; Abu Ghoush, M.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Osaili, T.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Liu, S.Q.; Shah, N.P. The potential application of probiotics and prebiotics for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. NPJ Sci. Food 2020, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Ward, S.A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; El-Omar, E.M. Considering the Effects of Microbiome and Diet on SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Nanotechnology Roles. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5179–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, K. The intestinal microbiota and its role in human health and disease. J. Med. Investig. JMI 2016, 63, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.J.; Wu, E. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanzaro, M.; Fagiani, F.; Racchi, M.; Corsini, E.; Govoni, S.; Lanni, C. Immune response in COVID-19: Addressing a pharmacological challenge by targeting pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.; Hossain, N.; Kashem, M.A.; Shahid, M.A.; Alam, A. Immune response in COVID-19: A review. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1619–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfaoglu, B.; Almeida-Santos, J.; Tye, C.A.; Satou, Y.; Ono, M. T-Cell Hyperactivation and Paralysis in Severe COVID-19 Infection Revealed by Single-Cell Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Tang, J.; Ye, C.; Dong, L. The immunology of COVID-19: Is immune modulation an option for treatment? Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, e428–e436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, N.; Rezaei, N. Lymphopenia in COVID-19: Therapeutic opportunities. Cell Biol. Int. 2020, 44, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.; Pranata, R. Lymphopenia in severe coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Intensive Care 2020, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Ding, J.; Huang, Q.; Tang, Y.-Q.; Wang, Q.; Miao, H. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: A descriptive and predictive study. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakolpour, S.; Rakhshandehroo, T.; Wei, E.X.; Rashidian, M. Lymphopenia during the COVID-19 infection: What it shows and what can be learned. Immunol. Lett. 2020, 225, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, B.; Wang, C.; Tan, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Ning, L.; Chen, L.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; et al. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiecki, M.; Colonna, M. Type I interferons: Diversity of sources, production pathways and effects on immune responses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, G.J.; Chen-Liaw, A.; Cossarini, F.; Livanos, A.E.; Spindler, M.P.; Plitt, T.; Eggers, J.; Mogno, I.; Gonzalez-Reiche, A.; Siu, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA and limited inflammatory cytokines are present in the stool of select patients with acute COVID-19. medRxiv 2020. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Long, W.; Tu, M.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, W.; Chen, D.; Zhou, L.; Wang, M.; et al. Lymphocyte subset (CD4+, CD8+) counts reflect the severity of infection and predict the clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 318–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Zhang, B.; Huang, H.; Luo, Y.; Wu, S.; Tang, G.; Liu, W.; Mao, L.; Mao, L.; Wang, F.; et al. Using IL-2R/lymphocytes for predicting the clinical progression of patients with COVID-19. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 201, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, D.; Mohanty, A. Gut microbiota and Covid-19- possible link and implications. Virus Res. 2020, 285, 198018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva-Zatorsky, N.; Sefik, E.; Kua, L.; Pasman, L.; Tan, T.G.; Ortiz-Lopez, A.; Yanortsang, T.B.; Yang, L.; Jupp, R.; Mathis, D.; et al. Mining the Human Gut Microbiota for Immunomodulatory Organisms. Cell 2017, 168, 928–943.e911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, S.S.; Kohl, K.D. Optimal integration between host physiology and functions of the gut microbiome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Reddy, D.N. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.M.; Sun, E.W.; Rogers, G.B.; Keating, D.J. The Influence of the Gut Microbiome on Host Metabolism Through the Regulation of Gut Hormone Release. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budden, K.F.; Gellatly, S.L.; Wood, D.L.; Cooper, M.A.; Morrison, M.; Hugenholtz, P.; Hansbro, P.M. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, A.; Bernard, L.; Poquet, Y.; Lugo-Villarino, G.; Neyrolles, O. The role of the lung microbiota and the gut-lung axis in respiratory infectious diseases. Cell. Microbiol. 2018, 20, e12966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaud, R.; Prevel, R.; Ciarlo, E.; Beaufils, F.; Wieërs, G.; Guery, B.; Delhaes, L. The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.G.; Qin, L.; Puah, S.H. COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): Clinical features and differences from typical pre-COVID-19 ARDS. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 213, 54–56.e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Tonetti, T.; Protti, A.; Langer, T.; Girardis, M.; Bellani, G.; Laffey, J.; Carrafiello, G.; Carsana, L.; Rizzuto, C.; et al. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: A multicentre prospective observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lelie, D.; Taghavi, S. COVID-19 and the Gut Microbiome: More than a Gut Feeling. mSystems 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Schultz, M.J.; van der Poll, T.; Schouten, L.R.; Falkowski, N.R.; Luth, J.E.; Sjoding, M.W.; Brown, C.A.; Chanderraj, R.; Huffnagle, G.B.; et al. Lung Microbiota Predict Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, W.; Fu, Y.; Yue, L.; Chen, G.-d.; Cai, X.; Shuai, M.; Xu, F.; Yi, X.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.J.; et al. Gut microbiota may underlie the predisposition of healthy individuals to COVID-19. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Zhou, F.; Jin, T.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, H. The characteristics and predictive role of lymphocyte subsets in COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Nie, H.X.; Hu, K.; Wu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.T.; Wang, M.M.; Wang, T.; Zheng, Z.S.; Li, X.C.; Zeng, S.L. Abnormal immunity of non-survivors with COVID-19: Predictors for mortality. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, L.E.; Kollef, M.H.; Casale, T.B. Probiotic prophylaxis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: A blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Wang, C.T.; Zhang, F.S.; Qi, F.; Wang, S.F.; Ma, S.; Wu, T.J.; Tian, H.; Tian, Z.T.; Zhang, S.L.; et al. Effect of probiotics on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients: A randomized controlled multicenter trial. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, G.; Scagnolari, C.; Pugliese, F.; Mastroianni, C.M.; d’Ettorre, G. Probiotics and COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, J.W.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; Ng, S.C. Probiotics and COVID-19: One size does not fit all. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 644–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).