Disinfectant Susceptibility of Biofilm Formed by Listeria monocytogenes under Selected Environmental Conditions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

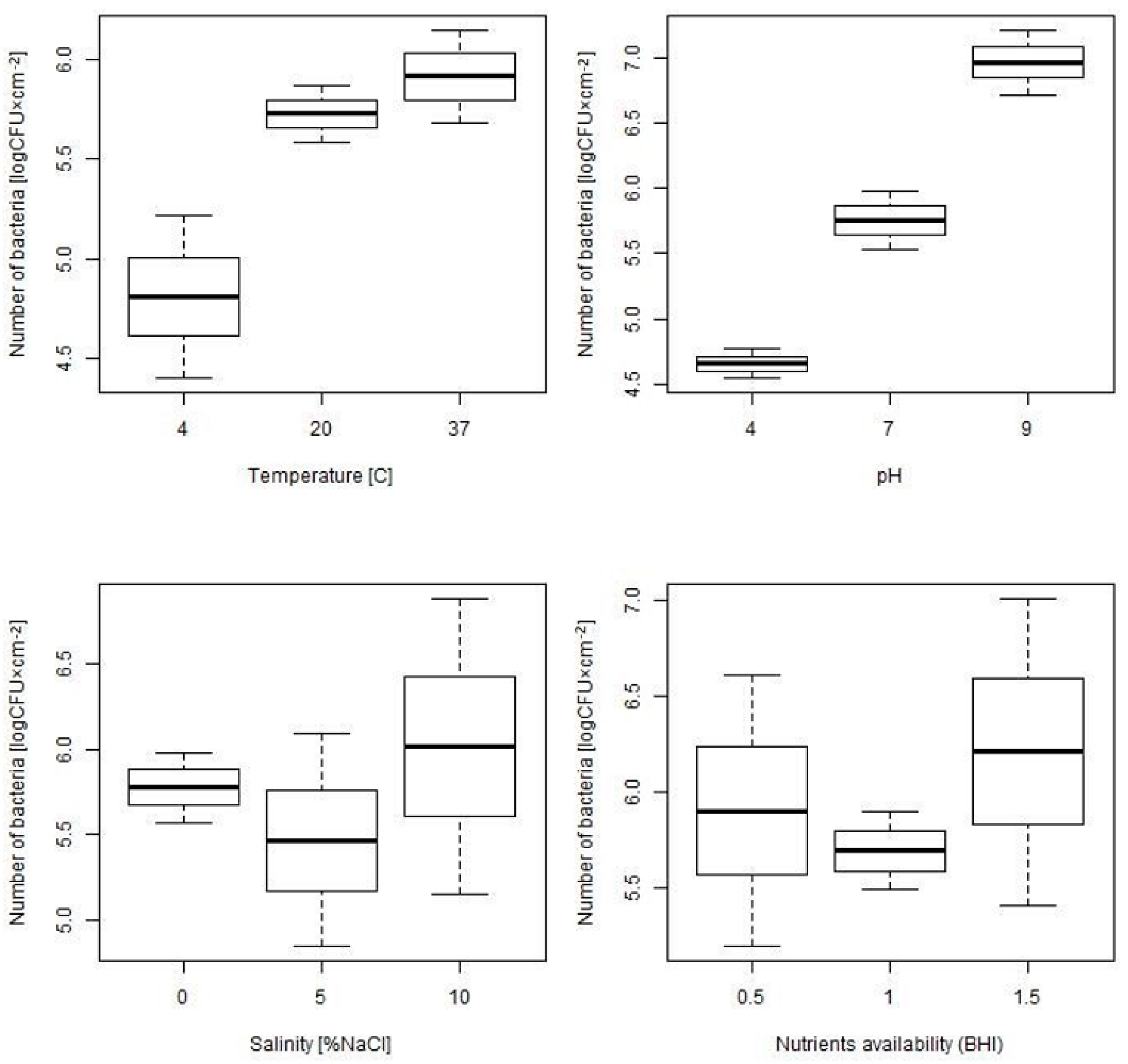

2.1. Assessment of Biofilm Formation Ability under Different Environmental Conditions

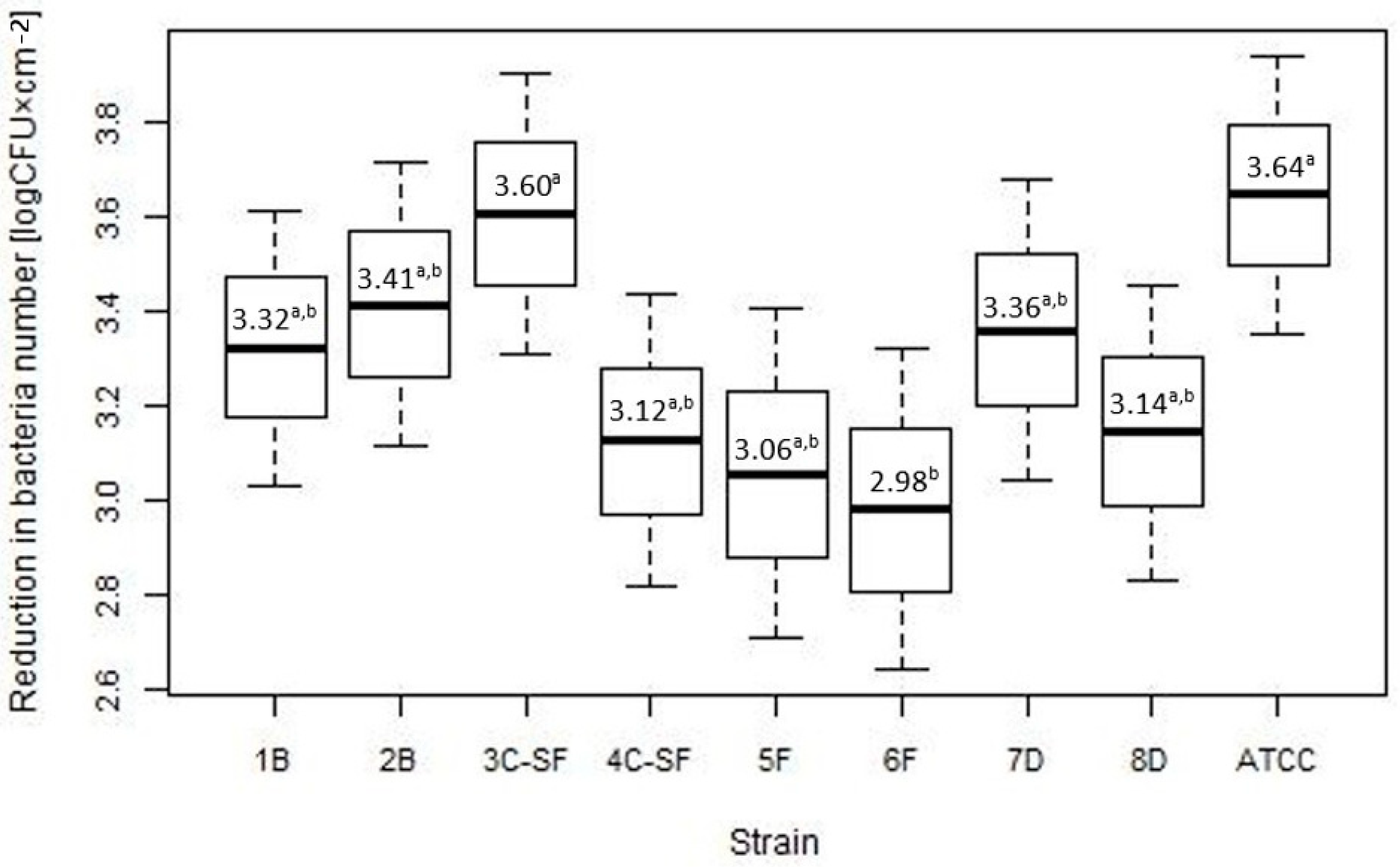

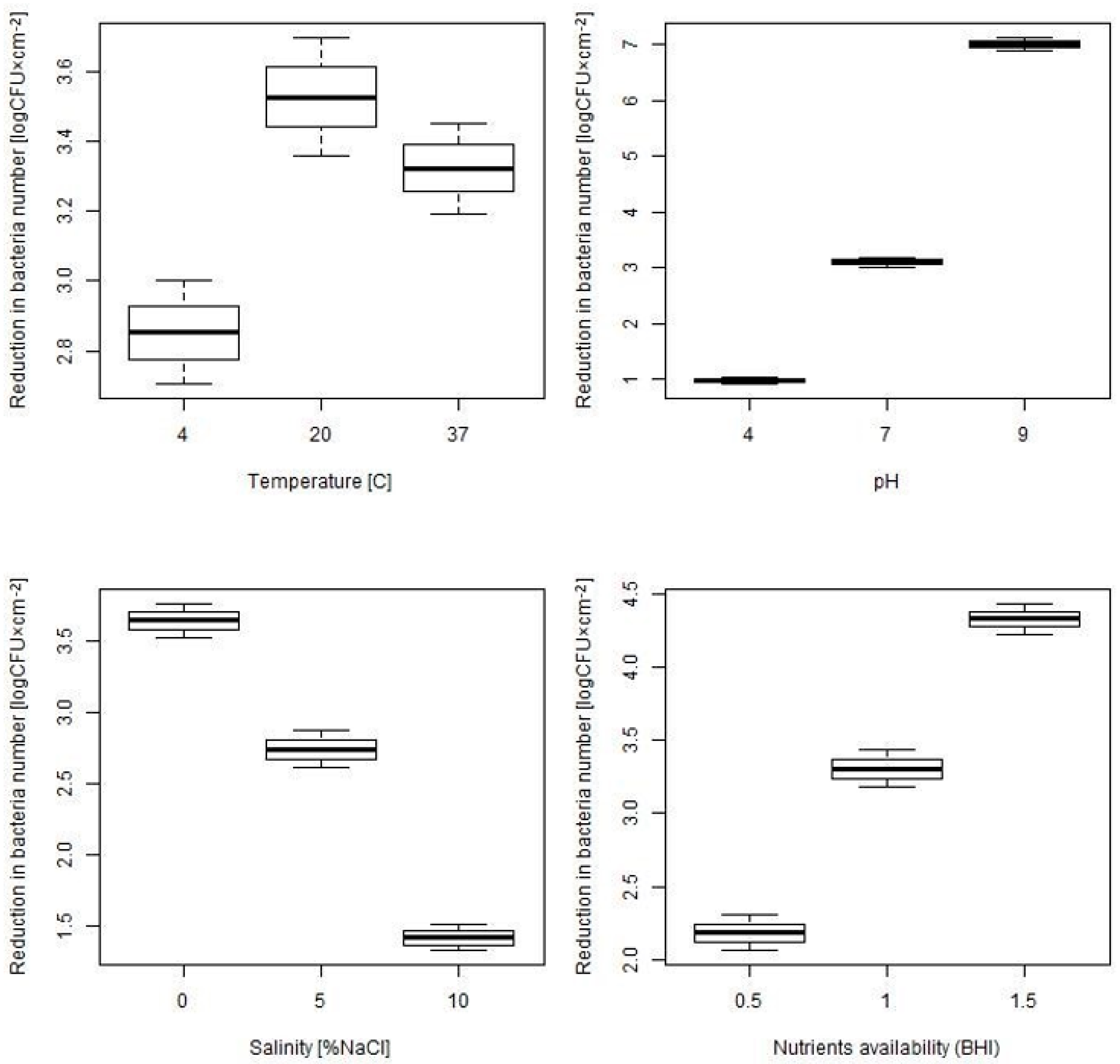

2.2. Assessment of Disinfectant Susceptibility of Biofilm Formed under Different Environmental Conditions

3. Discussion

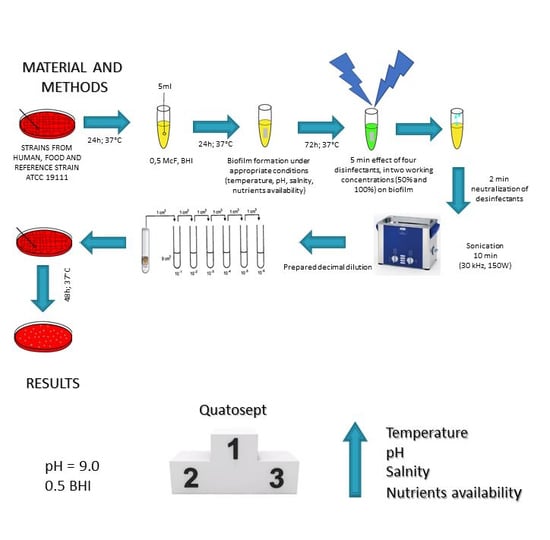

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains

4.2. Biofilm Formation of L. monocytogenes Strains on Stainless Steel Coupons

4.3. Determination of Anti-Biofilm Efficacy of Selected Disinfectants

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jami, M.; Ghanbari, M.; Zunabovic, M.; Doming, K.J.; Kneifel, W. Listeria monocytogenes in Aquatic Food Products-A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczycka, M. Metody inaktywacji i hamowania wzrostu Listeria monocytogenes w przetworach mięsnych. Żywność. Nauka. Technologia. Jakość 2005, 12, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2017. EFSA J. 2018, 12, 5500. [Google Scholar]

- Doijad, S.P.; Barbuddhe, S.B.; Garg, S.; Poharkar, K.V.; Kalorey, D.R.; Kurkure, N.V.; Rawool, D.B.; Chakraborty, T. Biofilm-Forming Abilities of Listeria monocytogenes Serotypes Isolated from Different Sources. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, J.; Andrew, P.W.; Faleiro, M.L. Listeria monocytogenes in cheese and the dairy environment remains a food safety challenge: The role of stress responses. Food Res. Int. 2015, 67, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, C.; Oulahal, N.; Chamba, J.-F.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F.; Notz, E.; Briandet, R. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by resident biofilms present on wooden shelves used for cheese ripening. Food Control 2011, 22, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houdt, R.; Michiels, C.W. Biofilm formation and the food industry, a focus on the bacterial outer surface. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoodley, P.; Hall-Stoodley, L.; Costerton, B.; DeMeo, P.; Shirtliff, M.; Gawalt, E. Biofilms, Biomaterials, and Device-Related Infections. In Handbook of Polymer Applications in Medicine and Medical Devices; Modjarrad, K., Ebnesajjad, S., Eds.; William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 556–583. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, N.; Zheng, Y.; Opoku-Temeng, C.; Du, Y.; Bonsu, E.; Sintim, H.O. Biofilm formation mechanisms and targets for developing antibiofilm agents. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møretrø, T.; Langsrud, S. Listeria monocytogenes: Biofilm formation and persistence in food-processing environments. Biofilms 2004, 1, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, M.; Chojnowski, W.; Nowak, H. Disinfection in diaryplants. Nauki Inżynieryjskie i Technologie 2014, 15, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Muhterem-Uyar, M.; Dalmasso, M.; Bolocan, A.S.; Hernandez, M.; Kapetanakou, A.E.; Kuchta, T.; Manios, S.G.; Melero, B.; Minarovicova, J.; Nicolau, A.I.; et al. Environmental sampling for Listeria monocytogenes control in food processing facilities reveals three contamination scenarios. Food Control 2015, 51, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.; Larsen, M.H.; Ingmer, H.; Vogel, B.F.; Gram, L. Sodium chloride enhances adherence and aggregation and strain variation influences invasiveness of Listeria monocytogenes strains. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Singh, S.K.; Chowdhury, I.; Singh, R. Understanding the mechanism of bacterial biofilms resistance to antimicrobial agents. Open Microbiol. J. 2017, 11, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadam, S.R.; den Besten, H.M.W.; van der Veen, S.; Zwietering, M.H.; Moezelaar, R.; Abee, T. Diversity assessment of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation: Impact of growth condition, serotype and strain origin. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 165, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poimenidou, S.; Belessi, C.A.; Giaouris, E.D.; Gounadaki, A.S.; Nychas, G.-J.E.; Skandamis, P.N. Listeria monocytogenes Attachment to and Detachment from Stainless Steel Surfaces in a Simulated Dairy Processing Environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7182–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonsaglia, E.C.R.; Silva, N.C.C.; Fernades, A.J.; Araujo, J.P.J.; Tsunemi, M.H.; Rall, V.L.M. Production of biofilm by Listeria monocytogenes in different materials and temperatures. Food Control 2014, 35, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poimenidou, S.V.; Chrysadakou, M.; Tzakoniati, A.; Bikouli, V.C.; Nychas, G.-J.; Skandamis, P.N. Variability of Listeria monocytogenes strains in biofilm formation on stainless steel and polystyrene materials and resistance to peracetic acid and quaternary ammonium compounds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 237, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordwell, S.J. Technologies for bacterial surface proteomics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.J.; Archer, P.; Banks, J.G. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes at refrigeration temperatures. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1990, 68, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontinen, A.; Markkula, A.; Lindstrom, M.; Korkeala, H. Two-componentsystem histidine kinases involved in growth of Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3994–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-H.; Hébraud, M.; Bernardi, T. Increased adhesion of Listeria monocytogenes strains to abiotic surfaces under cold stress. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, J.; Cruz, C.D.; Palmer, J.; Fletcher, G.C.; Flint, S. Biofilm formation of the L. monocytogenes strain 15G01 is influenced by changes in environmental conditions. J. Microbiol. Methods 2015, 119, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetin, M.S.; Zhang, C.; Hutkins, R.W.; Benson, A.K. Regulation of transcription of compatible solute transporters by the general stress sigma factor, sigmaB, in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.; Viala, D.; Chambon, C.; Esbelin, J.; Hébraud, M. Listeria monocytogenes Biofilm Adaptation to Different Temperatures Seen Through Shotgun Proteomics. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tresse, O.; Lebret, V.; Benezech, T.; Faille, C. Comparative evaluation of adhesion, surface properties, and surface protein composition of Listeria monocytogenes strains after cultivation at constant pH of 5 and 7. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 101, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herald, P.J.; Zottola, E.A. Attachment of Listeria monocytogenes to Stainless Steel Surfaces at Various Temperatures and pH Values. J. Food Sci. 1988, 53, 1549–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, R.E.; Ross, T.; Bowman, J.P. Variability in biofilm production by Listeria monocytogenes correlated to strain origin and growth conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 150, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belessi, C.-E.A.; Gounadaki, A.S.; Psomas, A.N.; Skandamis, P.N. Efficiency of different sanitation methods on Listeria monocytogenes biofilms formed under various environmental conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, S46–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zou, Y.; Lee, H.-Y.; Ahn, J. Effect of NaCl on the biofilm formation by foodborne pathogens. J. Food Sci. 2010, 9, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Breidt, F.; Gorski, L. Synergistic Effects of Sodium Chloride, Glucose, and Temperature on Biofilm Formation by Listeria monocytogenes Serotype 1/2a and 4b Strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Chai, L.C.; Pui, C.F.; Mustafa, S.; Cheah, Y.K.; Nishibuchi, M. Formation of biofilm by Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19112 at different incubation temperatures and concentrations of sodium chloride. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caly, D.; Takilt, D.; Lebret, V.; Tresse, O. Sodium chloride affects Listeria monocytogenes adhesion to polystyrene and stainless steel by regulating flagella expression. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 49, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherifi, T.; Jacques, M.; Quessy, S.; Fravalo, P. Impact of Nutrient Restriction on the Structure of Listeria monocytogenes Biofilm Grown in a Microfluidic System. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeraik, A.E.; Nitschke, M. Influence of growth media and temperature on bacterial adhesion to polystyrene surfaces. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2012, 55, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Folsom, J.P.; Siragusa, G.R.; Frank, J.F. Formation of biofilm at different nutrient levels by various genotypes of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 2006, 69, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhowlaghar, N.; Abeysundara, P.D.A.; Nannapaneni, R.; Schilling, M.W.; Chang, S.; Cheng, W.-H. Growth and Biofilm Formation by Listeria monocytogenes in Catfish Mucus Extract on Four Food Contact Surfaces at 22 and 10 °C and Their Reduction by Commercial Disinfectants. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piercey, M.J.; Ells, T.C.; Macintosh, A.J.; Hansen, L.T. Variations in biofilm formation, desiccation resistance and Benzalkonium chloride susceptibility among Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated in Canada. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 257, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarnisalo, K.; Lundén, J.; Korkeala, H.; Wirtanen, G. Susceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes strains to disinfectants and chlorinated alkaline cleaners at cold temperatures. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastbjerg, V.G.; Gram, L. Model systems allowing quantification of sensitivity to disinfectants and comparison of disinfectant susceptibility of persistent and presumed nonpersistent Listeria monocytogenes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 1667–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.-J.; Frank, J.F. Susceptibility of Starved Planktonic and Biofilm Listeria monocytogenes to Quaternary Ammonium Sanitizer as Determined by Direct Viable and Agar Plate Counts. J. Food Prot. 1993, 56, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostaki, M.; Chorianopoulos, N.; Braxou, E.; Nychas, G.-J.; Giaouris, E. Differential Biofilm Formation and Chemical Disinfection Resistance of Sessile Cells of Listeria monocytogenes Strains under Monospecies and Dual-Species (with Salmonella enterica) Conditions. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 2586–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaitiemwong, N.; Hazeleger, W.C.; Beumer, R.R. Inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes by Disinfectants and Bacteriophages in Suspension and Stainless Steel Carrier Tests. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 2012–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszewska, M.A.; Zhao, T.; Doyle, M.P. Inactivation and induction of sublethal injury of Listeria monocytogenes in biofilm treated with various sanitizers. Food Control 2016, 70, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Frank, J.F. Effect of growth temperature and media on inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes by chlorine. J. Food Saf. 1991, 11, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoui, D.; Hirokawa, E.; Takahashi, H.; Kuda, T.; Kimura, B. Effect of glucose on Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation, and assessment of the biofilm’s sanitation tolerance. Biofouling 2016, 32, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Breakpoints Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zones Diameters. Version 8.0. Available online: http://www.eucast.org/ast_of_bacteria/previous_versions_of_documents/2018 (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Hard Water PN-EN-1276. Chemiczne Środki Dezynfekcyjne i Antyseptyczne—Ilościowa Zawiesinowa Metoda Określania Działania Bakteriobójczego Chemicznych Środków Dezynfekcyjnych i Antyseptycznych Stosowanych w Sektorze Żywnościowym, Warunkach Przemysłowych i Domowych oraz Zakładach Użyteczności Publicznej—Metoda Badania i Wymagania (Faza 2, Etap 1). Available online: http://sklep.pkn.pl/pn-en-1276-2010e.html (accessed on 20 June 2019).

| Strain | n | Mean (log CFU × cm−2) (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 B | 18 | 5.71 (1.24) | 0.161 |

| 2 B | 18 | 5.73 (1.29) | |

| 3 C-SF | 18 | 5.85 (1.19) | |

| 4 C-SF | 18 | 5.55 (1.33) | |

| 5 F | 18 | 5.69 (1.33) | |

| 6 F | 18 | 6.28 (1.10) | |

| 7 D | 18 | 6.06 (1.14) | |

| 8 D | 18 | 5.77 (1.45) | |

| ATCC | 18 | 5.28 (1.17) |

| Number of Bacteria (log CFU × cm−2) | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Temperature | ||||||

| 4 °C, n = 18 | 20 °C, n = 18 | 37 °C, n = 126 | p | p 4–20 | p 4–37 | p 20–37 |

| 4.81 (0.83) | 5.73 (0.29) | 5.91 (1.33) | 0.001 | 0.036 | 0.001 | 0.541 |

| pH | ||||||

| pH 4, n = 18 | pH 7, n = 126 | pH 9, n = 18 | p | p 4–7 | p 4–9 | p 7–9 |

| 4.66 (0.23) | 5.76 (1.26) | 6.96 (0.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Salinity | ||||||

| Salinity 0%, n = 126 | Salinity 5%, n = 18 | Salinity 10%, n = 18 | p | p 0–5 | p 0–10 | p 5–10 |

| 5.78 (1.17) | 5.47 (1.25) | 6.02 (1.75) | 0.744 | / | / | / |

| Nutrients Availability | ||||||

| Nutrients availability 0.5, n = 18 | Nutrients availability 1, n = 126 | Nutrients availability 1.5, n = 18 | p | p 0.5–1 | p 0.5–1.5 | p 1–1.5 |

| 5.9 (1.44) | 5.69 (1.16) | 6.21 (1.62) | 0.460 | / | / | / |

| Factors | Value (log CFU × cm−2) | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 5.95 | 0.12 | 49.1 | <0.001 |

| Temperature 4 vs. 37 | −1.15 | 0.28 | −4.12 | <0.001 |

| Temperature 20 vs. 37 | −0.23 | 0.28 | −0.82 | 0.414 |

| pH 4 vs. 7 | −1.3 | 0.28 | −4.65 | <0.001 |

| pH 9 vs. 7 | 1.01 | 0.28 | 3.62 | <0.001 |

| Disinfectant | n | Mean (log CFU × cm−2) (SD) | Jodat | Peroxat | Chlorox S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | p-Value | p-Value | |||

| Jodat | 324 | 3.04 (1.91) | |||

| Peroxat | 324 | 3 (1.89) | 0.772 | ||

| Chlorox S | 324 | 3.43 (1.91) | 0.012 | 0.006 | |

| Quatosept | 324 | 3.71 (1.84) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.078 |

| Disinfectant Concentration | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| 50% work solution | 100% work solution | |

| Mean reduction in bacteria number (SD) | ||

| n = 648 | n = 648 | |

| 2.81 (1.83) | 3.78 (1.87) | <0.001 |

| Number of Bacteria (log CFU× cm−2) | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), n = 144 | Mean (SD), n = 144 | Mean (SD), n = 1008 | ||||

| Temperature (°C) | ||||||

| 4 °C | 20 °C | 37 °C | p | p 4–20 | p 4–37 | p 20–37 |

| 2.85 (0.9) | 3.53 (1.03) | 3.32 (2.09) | 0.045 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.229 |

| pH | ||||||

| pH 4 | pH 7 | pH 9 | p | p 4–7 | p 4–9 | p 7–9 |

| 0.96 (0.38) | 3.1 (1.34) | 7.01 (0.73) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Salinity (% NaCl) | ||||||

| 0% | 5% | 10% | p | p 0–5 | p 0–10 | p 5–10 |

| 3.64 (1.97) | 2.74 (0.79) | 1.42 (0.55) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Nutrients Availability (BHI) | ||||||

| 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | p | p 0.5–1 | p 0.5–1.5 | p 1–1.5 |

| 2.18 (0.75) | 3.30 (2.05) | 4.32 (0.65) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Factor | Value | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 4.549 | 0.091 | 49.801 | <0.001 |

| Disifectant | ||||

| Jodat vs Quatosept | −0.669 | 0.038 | −17.599 | <0.001 |

| Peroxat vs Quatosept | −0.712 | 0.038 | −18.73 | <0.001 |

| Chlorox S vs Quatosept | −0.274 | 0.038 | −7.198 | <0.001 |

| Disinfectant Concentration | ||||

| Concentration 100 vs 50 | 0.964 | 0.027 | 35.86 | <0.001 |

| Temperature | ||||

| Temp 4 vs. 37 | −1.764 | 0.057 | −30.926 | <0.001 |

| Temp 20 vs. 37 | −1.09 | 0.057 | −19.108 | <0.001 |

| pH | ||||

| pH 4 vs. 7 | −3.652 | 0.057 | −64.025 | <0.001 |

| pH 9 vs. 7 | 2.393 | 0.057 | 41.961 | <0.001 |

| Salinity | ||||

| Zasol 5 vs. 0 | −1.876 | 0.057 | −32.896 | <0.001 |

| Zasol 10 vs. 0 | −3.196 | 0.057 | −56.036 | <0.001 |

| Nutrients Availability (BHI) | ||||

| Dost 0.5 vs. 1 | −2.433 | 0.057 | −42.652 | <0.001 |

| Dost 1.5 vs. 1 | −0.292 | 0.057 | −5.118 | <0.001 |

| Changing Environment Parameter | Experimental Conditions | Temperature | pH | Salinity | Nutrient Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 1 | 4 °C | 7 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.0 |

| 2 | 20 °C | 7 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.0 | |

| 3 | 37 °C | 7 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.0 | |

| pH | 4 | 37 °C | 4 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.0 |

| 5 | 37 °C | 7 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.0 | |

| 6 | 37 °C | 9 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.0 | |

| Salinity | 7 | 37 °C | 7 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.0 |

| 8 | 37 °C | 7 | 5% NaCl | BHI 1.0 | |

| 9 | 37 °C | 7 | 10% NaCl | BHI 1.0 | |

| Nutrients availability | 10 | 37 °C | 7 | 0% NaCl | BHI 0.5 * |

| 11 | 37 °C | 7 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.0 * | |

| 12 | 37 °C | 7 | 0% NaCl | BHI 1.5 * |

| Disinfectant | Active Substance | Producer | Working Concentration | pH of Solution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% WS * | 100% WS | ||||

| Quatosept | alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride | Galvet | 2.5 mL/L | 6.9 | 7.2 |

| Peroxat | peractetic acid, hydrogen peroxide | Agro-trade | 5 mL/L | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| Jodat | iodine | Agro-trade | 5 mL/L | 2.9 | 3.1 |

| Chlorox S | sodium hypochlorite | NTCE | 0.7% | 10.4 | 10.1 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skowron, K.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E.; Grudlewska, K.; Gajewski, P.; Wiktorczyk, N.; Wietlicka-Piszcz, M.; Dudek, A.; Skowron, K.J.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Disinfectant Susceptibility of Biofilm Formed by Listeria monocytogenes under Selected Environmental Conditions. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7090280

Skowron K, Wałecka-Zacharska E, Grudlewska K, Gajewski P, Wiktorczyk N, Wietlicka-Piszcz M, Dudek A, Skowron KJ, Gospodarek-Komkowska E. Disinfectant Susceptibility of Biofilm Formed by Listeria monocytogenes under Selected Environmental Conditions. Microorganisms. 2019; 7(9):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7090280

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkowron, Krzysztof, Ewa Wałecka-Zacharska, Katarzyna Grudlewska, Piotr Gajewski, Natalia Wiktorczyk, Magdalena Wietlicka-Piszcz, Andżelika Dudek, Karolina Jadwiga Skowron, and Eugenia Gospodarek-Komkowska. 2019. "Disinfectant Susceptibility of Biofilm Formed by Listeria monocytogenes under Selected Environmental Conditions" Microorganisms 7, no. 9: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7090280

APA StyleSkowron, K., Wałecka-Zacharska, E., Grudlewska, K., Gajewski, P., Wiktorczyk, N., Wietlicka-Piszcz, M., Dudek, A., Skowron, K. J., & Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. (2019). Disinfectant Susceptibility of Biofilm Formed by Listeria monocytogenes under Selected Environmental Conditions. Microorganisms, 7(9), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7090280