1. Introduction

Mesophilic, motile

Aeromonas spp. are responsible for ulcerative, hemorrhagic, and septicemic infections in freshwater and ornamental fish [

1]. While

A. hydrophila is the most cited, modern diagnostic tools [

2] have resulted in the identification of many more species implicated in disease development including A.

veronii,

A. bestiarum,

A. caviae,

A. jandaei,

A. piscicola,

A. schubertii, and

A. sobria. Amongst them,

A. veronii is increasingly gaining importance as a serious pathogen for the aquaculture industry. Outbreaks accompanied by significant losses have been reported in African catfish (

Clarias gariepinus), rajputi (

Puntius gonionotus), rui (

Labeo rohita), catla (

Catla catla), and shole (

Channas triatus) farmed in Bangladesh [

3], in Chinese longsnout catfish (

Leiocassis longirostris) [

4] loach (

Misgurnus anguillicaudatus), [

5] and cyprinid fish [

6] farmed in China and in ayu (

Plecoglossus altivelis) farmed in Japan [

7]. In addition to aquaculture,

A. veronii has also been reported to cause disease in ornamental fishes [

8].

During the past decade, A.

veronii bv.

sobria has become extremely problematic in the culture of European seabass (

Dicentrarchus labrax) in Greece. The disease first appeared in 2008 affecting a single fish farm in Central Greece [

9]. While it is still present in the specific farm, more farms in distant areas are also affected. At the beginning, the disease affected mainly fish reaching the commercial size (>200 g), but lately it has been reported to affect also younger fish with weight lower than 50 g. Outbreaks occur during the warm months of the year, when water temperature is over 21 °C. Cumulative mortality during outbreaks reaches >50%, if it is not treated with antibiotics and it is a major concern for the producers in the affected areas.

Affected fish appear lethargic with no appetite and in progressed stages of the disease they have an icteric appearance due to the highly haemolytic nature of the pathogen. Internally, multiple abscesses are usually found in the spleen and the kidney. Interestingly, the pathogen affects exclusively the European seabass and even during severe outbreaks, other fish species like the gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata), red porgy (Pagrus pagrus), and sharpsnout seabream (Diplodus puntazzo), which are cultured in adjacent sea cages of the affected areas are not infected (personal observations).

Over the past decade, we have collected a large number of A. veronii strains from European seabass of Greek aquaculture farms during disease outbreaks at various time points during the year. Here, we present a comparative study of 50 A. veronii clinical strains from different geographic areas. Biochemical diversity and phylogenetic relationships were assessed. Comparative genomic analysis was conducted to assess similarity at the genome level and to study putative virulence factors that may have contributed to pathogenicity. Pathogenicity was also tested in vivo using zebrafish as a model. We followed the principles of reverse vaccinology using the draft genomes of nine A. veronii strains, representatives of the geographic location, the phenotype, and the year of isolation in order to assess the antigenic diversity of the species in Greece. Through this study we identified and compared outer membrane proteins (OMPs) to establish the basis for effective strain selection for a future vaccine for seabass in the Aegean Sea. The final goal of this work was to acquire knowledge on the diversity of a novel pathogen and contribute to the management of a very important emerging disease for the Mediterranean aquaculture industry.

2. Materials and Methods

Localities included in the study were selected based on reports from the fish vets of the affected farms for aeromonad-suspected morbidity and mortality. Extended sampling was conducted in the area of Argolikos Bay where the disease was first described [

9]. Microbial screenings on diseased fish farmed in sea-cages, were conducted at various times (2009–2019) including periods of disease outbreaks but also periods when fish showed no signs of the disease. Only the positive for

Aeromonas spp. samplings are presented here. In the study we have also included samples from disease outbreaks in the ornamental freshwater fish Green swordtail (

Xiphophorus helleri) farmed in North/East Greece and in zebrafish (

Danio rerio) from the experimental facilities of the Biology Department of the University of Crete, Greece. Detailed information on the samplings conducted is presented in

Table 1.

Samples of fish and bacteria were either collected on site or were sent and processed at the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR). Fish underwent full necropsy and clinical signs of disease were recorded when present. Bacteria were isolated from the kidney of fish on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) (Trafalgar Scientific, Leicester, UK) supplemented with salt (2% NaCl) and on the selective for

Aeromonas spp. Aeromonas isolation agar (AIA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with ampicillin. Aeromonads detection was based on growth on AIA and positive PCR reaction for the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer region using genus-specific primers for

Aeromonas spp. [

10]. Subsequently, identification to genus level was achieved by PCR amplification of the extracellular lipase Glycerophospholipid-cholesterol acyltransferase (GCAT) gene [

11]. Only positive isolates (1–7 per sampling) were further analysed by random selection. For identification to species level, the gene of B-subunit of DNA gyrase (

gyrB) was amplified according to reference [

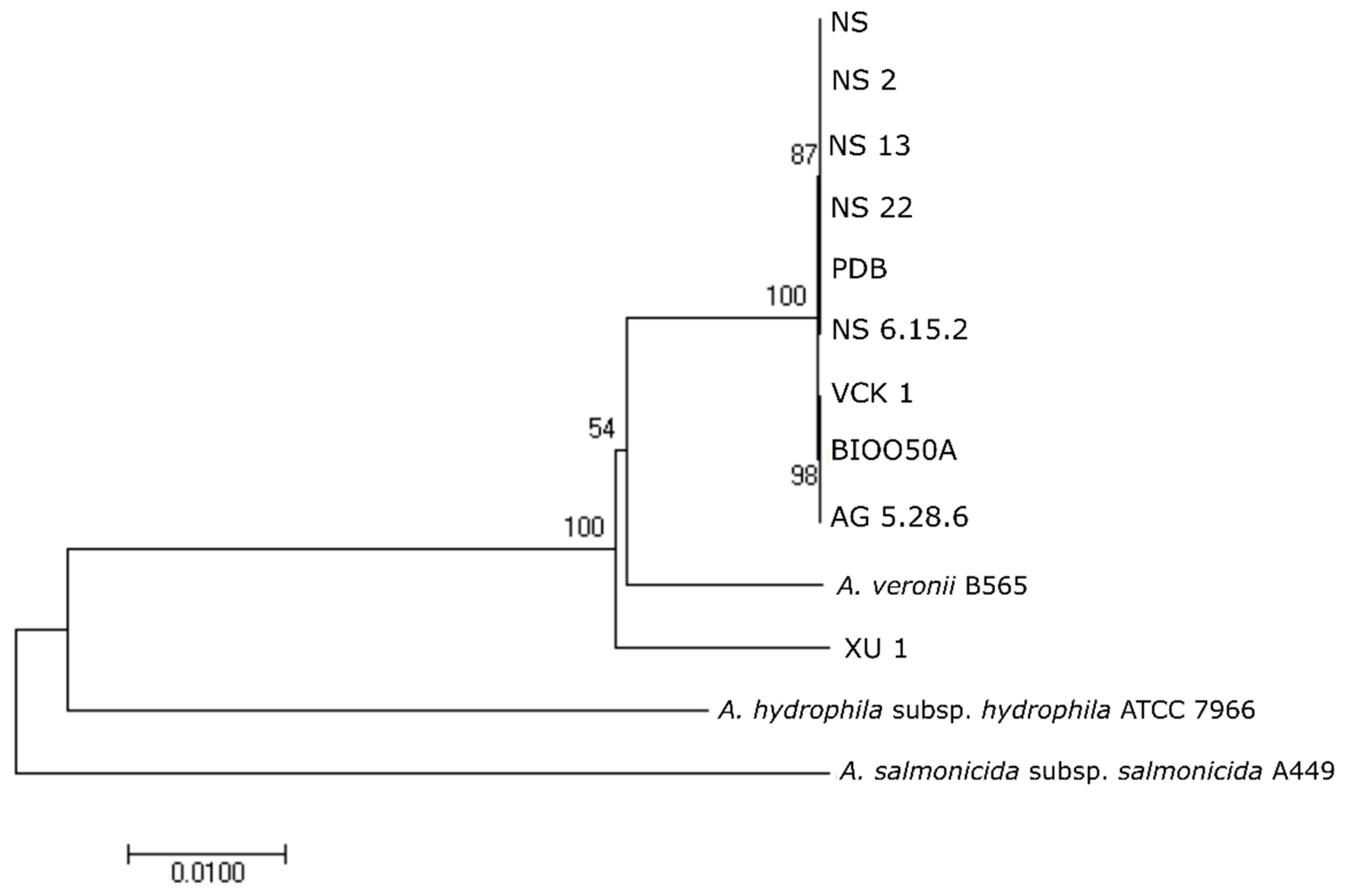

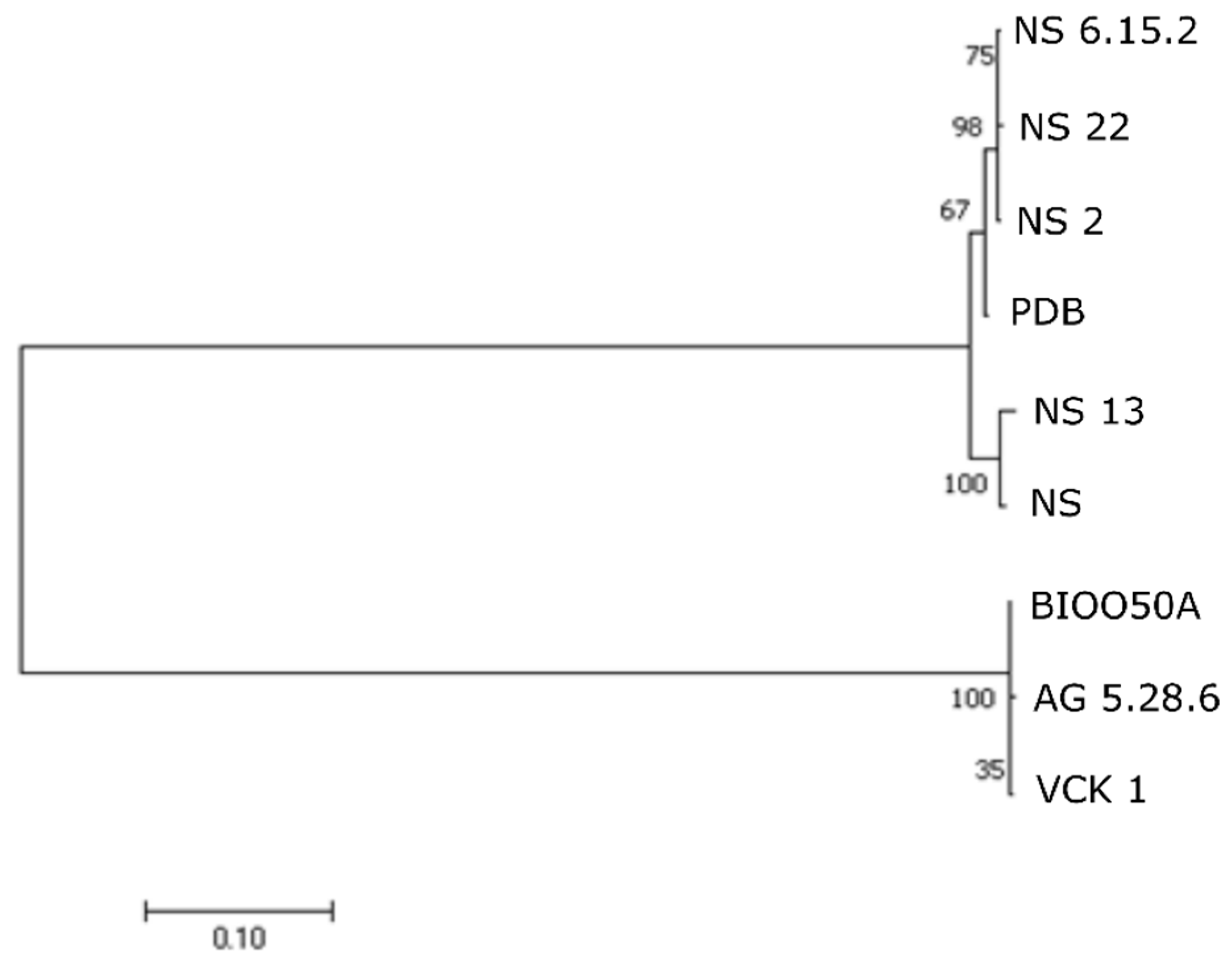

12] and sequenced in ABI3730xl sequencer based on the protocol of BigDye Terminators 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sequences were deposited to GenBank under the Accession Numbers: MN193961-MN193984 and MN193987-MN194010. The obtained sequences were compared in GenBank using the NCBI BLAST algorithms. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the sequences of

gyrB gene produced herein and sequences from all the

Aeromonas spp. known up to date. Alignment was performed in Clustal W [

13]. Genetic distances were estimated and phylogenetic relationships were examined with neighbor-joining (NJ) analyses [

14] in MEGA X [

15] under Tamura-Nei [

16] model of evolution. The confidence of tree nodes was tested by the bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates.

Colony morphology was observed on TSA. Motility was tested on motility, indole, and ornithine (MIO) medium (Sigma-Aldrich). Pigment production was tested on TSA and Mueller-Hinton agar (MH) (Trafalgar Scientific, Leicester, England) after incubation for 24–72 h, as well as their corresponding broths after incubation for 7 d.

Biochemical characterization was conducted with the commercial kits BIOLOG GEN III Microplate (BIOLOG) (Biolog, Hayward, CA, USA) and API 20E (bioMérieux Hellas S.A, Athens, Greece). Results were recorded after 24 h incubation for API 20E and after 48 h incubation for BIOLOG. BIOLOG and API 20E were also used for identification to genus level [

2]. Catalase reaction was tested separately. The TSA and MH mediums were supplemented with 0.5% NaCl. All tests were performed at 25 °C. The type strains LMG 3785 (

A. veronii bv.

sobria) and LMG 9075 (A.

veronii bv.

veronii) were included in all tests as reference strains. Hemolytic activity was tested on 5% seabass blood agar [

17]. Fish blood was taken aseptically from healthy European seabass broodfish maintained in the aquaculture facilities of HCMR. Results were recorded at 24 and 48 h incubation at 25 °C. Susceptibility to antibacterial agents was assessed by the disk diffusion method [

18] using 6-mm commercial disks (Oxoid, Thermo Fisher Scientific) on MH agar supplemented with 0.5% NaCl. The inhibition diameter was recorded after incubation for 48 h at 22–25 °C. Inhibition diameters were relatively set by Enterobacteriaceae and compared with relevant literature [

19,

20].

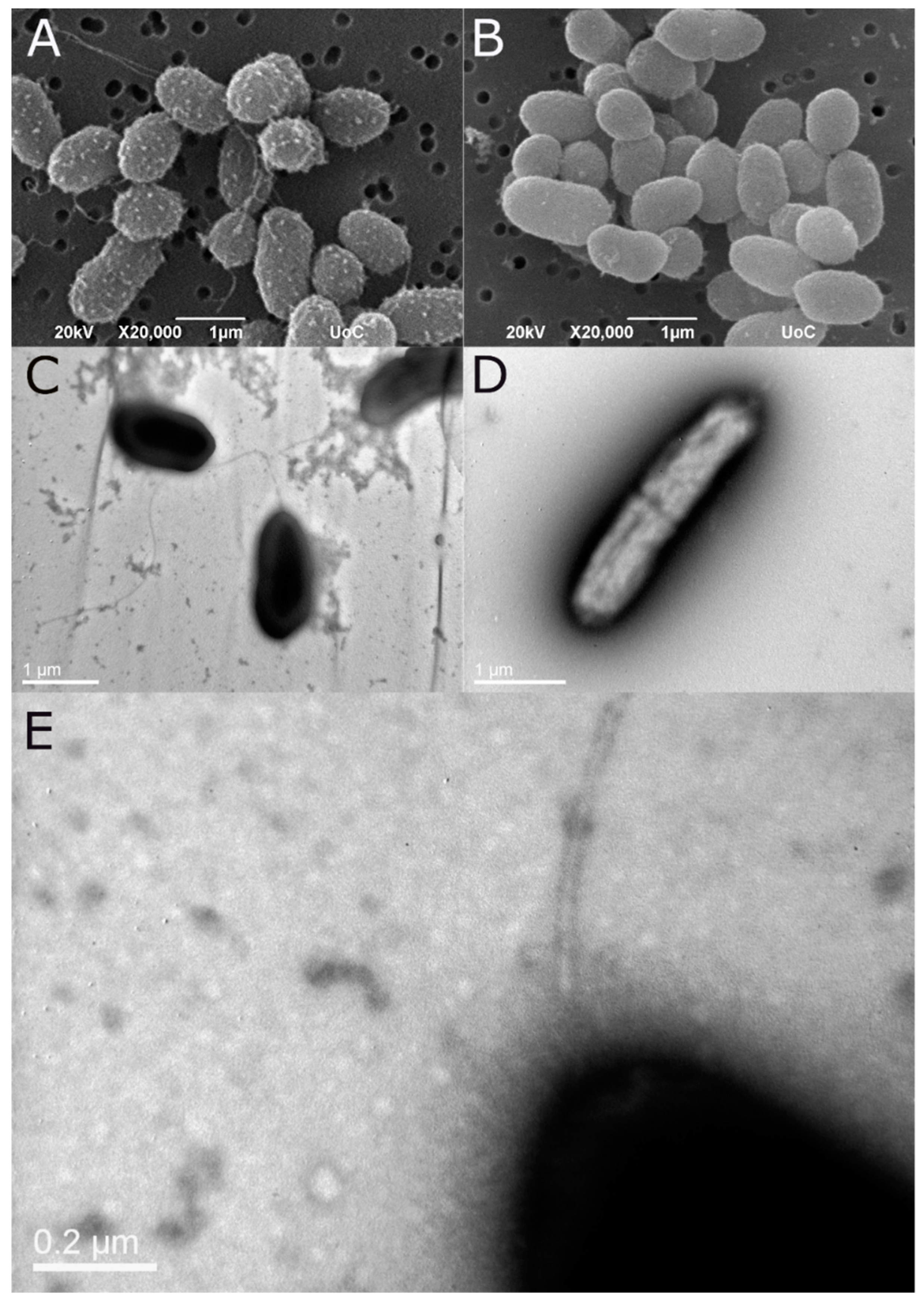

Morphology of the bacteria with emphasis on the cellular components related to motility (flagellum, fimbria, pili) was studied with transmission and scanning electron microscopy. Bacteria were grown for 6 hours in TSB and preserved in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer. Bacteria preparations were negatively stained with 4% (w/v) uranyl acetate (pH 7.2) and observed with a JOEL JEM2100 transmission electron microscope (TEM) operated at 80 kV. Samples for scanning electron microscope (SEM) were washed with sodium cacodylate buffer, post fixed with OsO4, and dehydrated in an ascending alcohol series, mounted on stubs, and sputter coated with gold-palladium. Bacteria were viewed using a JEOL JSM-6390LV scanning electronic microscope at 20 kV. Both TEM and SEM were conducted at the Electron Microscopy Laboratory of the University of Crete.

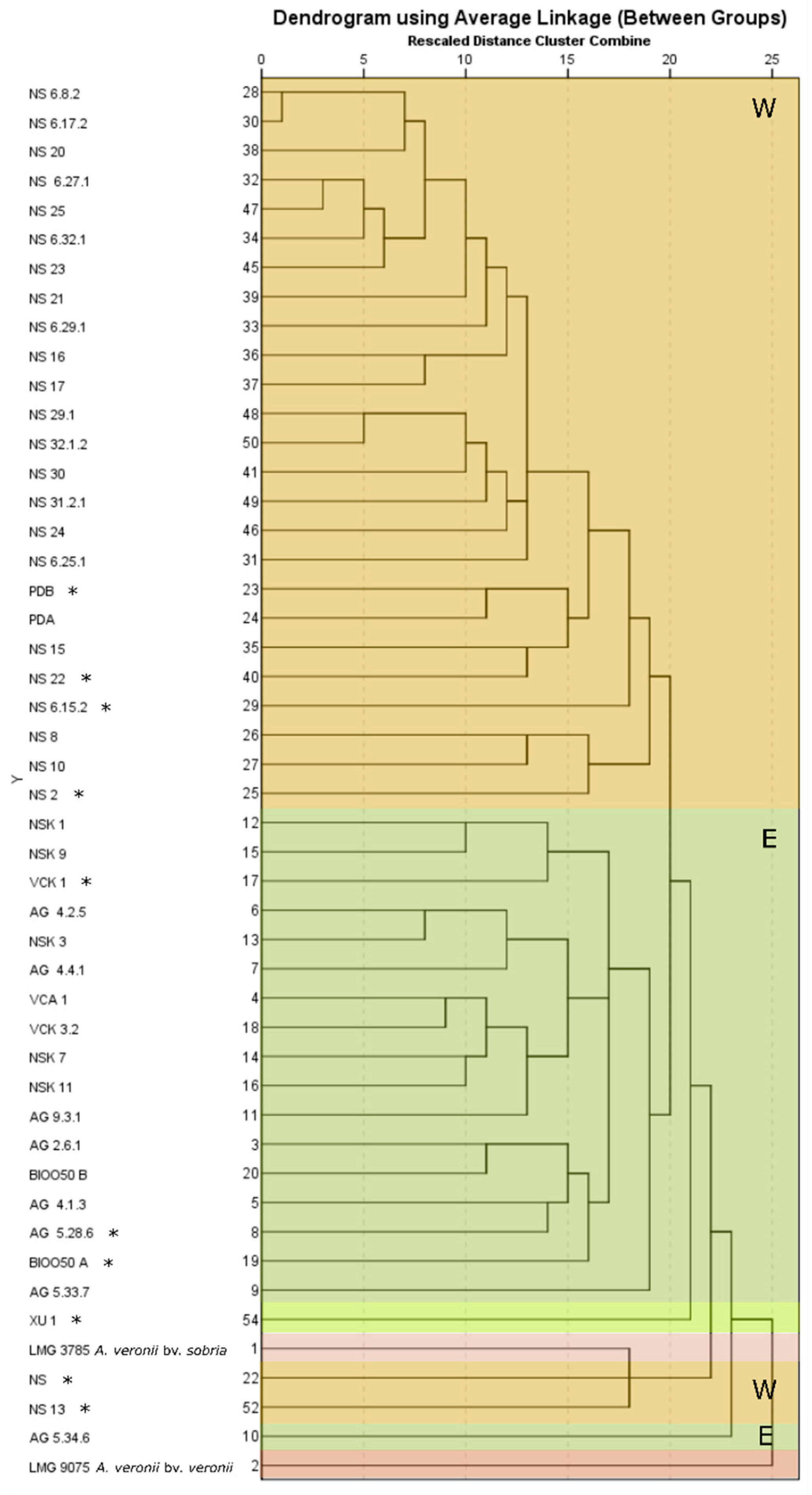

Hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted on the phenotypic and biochemical data tested including the API 20E, BIOLOG’s and catalase reactions, motility, pigment production, and β-hemolysis (119 characters). Analysis was conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics software using between-groups linkage method with Chi-Square measure.

Nine strains from seabass and one strain from

X. helleri were subjected to whole genome sequencing. Paired-end sequencing was performed using an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, Inc. San Diego, CA, USA). For the de novo assembly, MaSuRCa genome assembler and SPAdes were used [

21]. Quality of the assembled genome sequences was assessed by Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) [

22,

23]. Gene identification and annotation were done using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline [

24] and RAST [

25]. The bacterial genomes were also analyzed in the platform of the Pathosystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC) [

26]. Genomes were deposited to GenBank under the Accession Numbers: NZ_NMUR00000000.1 (NS), NZ_NMUS00000000.1 (PDB), NZ_NPKE00000000.1 (NS 2), NZ_NPKC00000000.1 (NS 6.15.2), NZ_NQMB00000000.1 (NS 13), NZ_NQMC00000000.1 (NS 22), NZ_NNSE00000000.1 (AG 5.28.6), NZ_NNSF00000000.1 (VCK 1), NZ_NPKD00000000.1 (BIOO50A), NZ_SSUX00000000.1 (XU 1).

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis was conducted based on the Web-based MLST sequence database (

https://pubmlst.org/aeromonas/) [

27,

28]. The allele sequences for the six genetic loci (

gyrB,

groL,

gltA,

metG,

ppsA, and

recA), were retrieved from the ten

Aeromonas genomes. The ST profile of each strain was created and compared in the database with other 645 different STs (July 2019). The complete sequences of the six genes were used a) to estimate the genetic distances among seabass strains and with the strains XU 1 and B565 (

A. veronii) and b) for phylogenetic analyses (NJ) following concatenation. Analyses were performed in MEGA X [

15] under the Tamura-Nei [

16] model of evolution. The confidence of tree nodes was tested by the bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates.

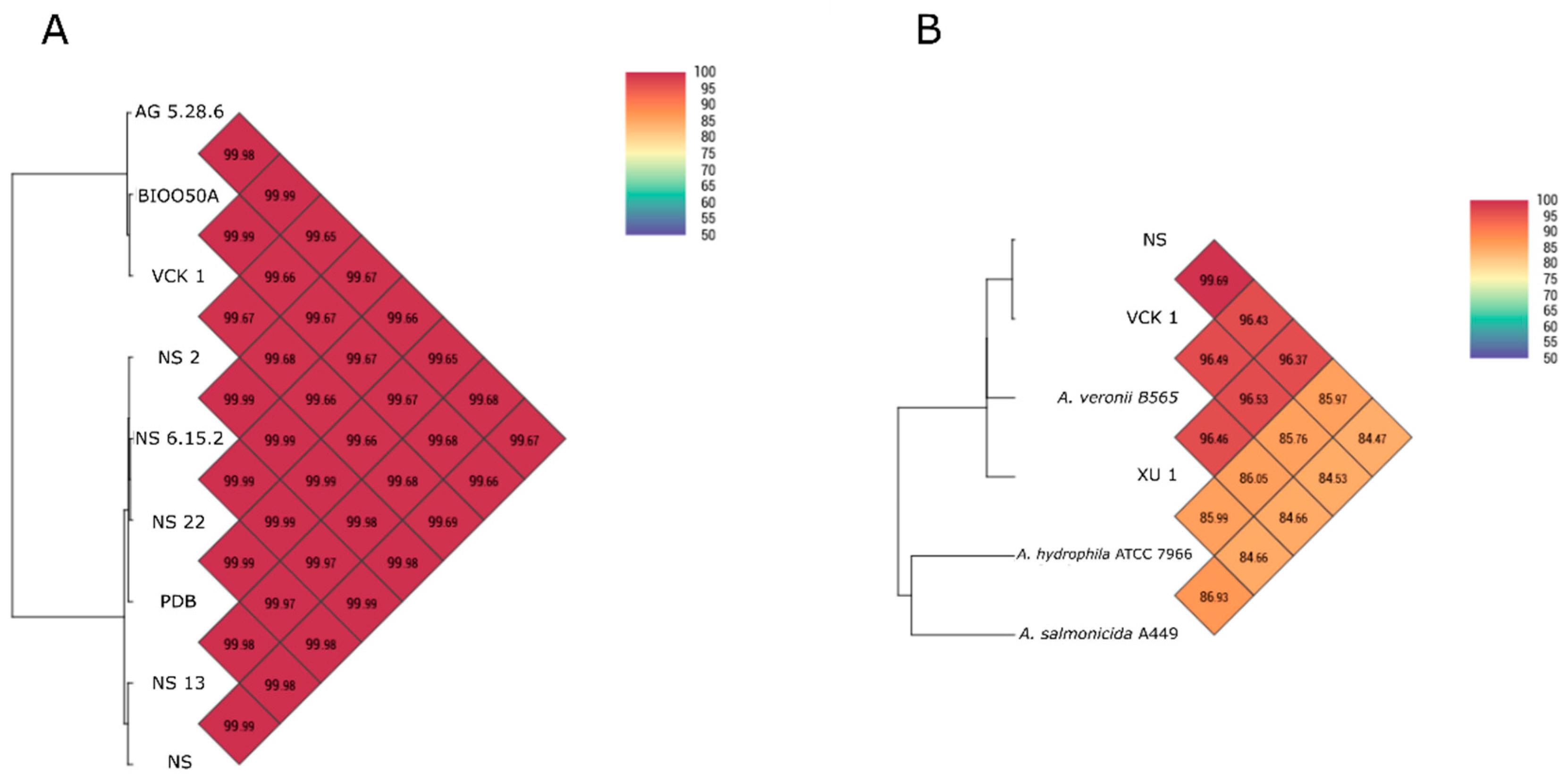

The similarity of the nine genomes isolated from seabass with each other and with other

Aeromonas spp. was assessed using Average Nucleotide Identity by Orthology [

29] with Ortho-ANI software. Comparisons with other

A. veronii genomes from different hosts and isolation sources, and the strain XU 1 from

X. helleri described here, and the strain A449 of

A. salmonicida subsp.

salmonicida and the type strain ATCC 7966 of

A. hydrophila subsp.

hydrophila, were also made.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) analysis was done according to [

30]. Briefly, SNPs were determined using CSI phylogeny [

31,

32] available on the CGE (

www.genomicepidemiology.org). The paired-end reads of the nine

Aeromonas strains were mapped to the reference chromosome of the strain B565. Qualified SNPs were determined when fulfilling the following criteria: (1) A minimum distance of 10 bps between each SNP, (2) a minimum of 10% of the relative depth at SNP positions, (3) the mapping quality was above 25, (4) the SNP quality was more than 30, and (5) all indels were excluded. The SNPs from each genome were concatenated to a single alignment corresponding to the position of the reference genome. The concatenated sequences were subjected to maximum likelihood analysis using MEGA X.

The profile of the outer membrane proteins (OMPs) was first studied in the randomly selected strain VCK 1. The proteome (as predicted by the genomic analysis) of VCK 1 was analyzed in PSORTb v.3.0, a tool for subcellular localization of proteins [

33]. The detected OMPs, were further analyzed with Signal IP v.5 in order to detect signal peptides (and cleavage sites) of proteins targeting the outer membrane [

34]. TOPCONS2 was used to predict the topology of alpha-helical transmembrane proteins [

35] and PRED-TMBB2 to predict the topology of beta-barrel proteins [

36]. The set of proteins identified in this way for VCK 1 were also located in the other

A. veronii strains from seabass, and from strains XU 1 from

X. helleri and strain B565 through mapping in Geneious v.9.1.6. Similarity of these proteins was calculated in Geneious using protein distance following alignment of the aminoacidic sequences with the MUSCLE algorithm.

Genomic Islands (GIs) were predicted for the nine isolates from seabass through the online platform Island Viewer v.3 [

37] that includes three methods, IslandPick, IslandPath-DIMOB, and SIGI-HMM, for prediction and detection of GIs. Prophage sequences were identified by the PHASTER web server [

38]. Virulence genes were detected manually and using the PATRIC annotation platform [

26], which combines three databases; PATRIC_VF, VFDB, and VICTORS. Incomplete coding sequences (CDS) located at the edge of contigs were excluded. Special focus was given to the secretion systems, flagellar proteins and toxins, which were studied using alignment with the respective gene clusters identified in the

Aeromonas strains of the current study. Alignment was conducted with CLUSTALW and Mauve [

39] in Geneious v.9.1.6. Antibiotic Resistance genes were predicted by the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) Software of the CARD platform [

40].

Adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) (mean weight: 0.3 g) were used for assessing the virulence of the nine A. veronii strains from seabass. Fish were acclimatized for at least ten days before handling. Water and room temperature were kept at 25 °C. For each strain, 50 fish were distributed in five 5-L tanks each containing 10 individuals. Five doses (108–104 cfu/fish) of live bacteria diluted in sterile PBS were injected in the experimental groups while the control group was injected with sterile PBS. The injection (10 μL/fish) was conducted using a Hamilton micro-syringe following anesthesia (MS222). The fish were monitored over a five-day period, dead fish were removed daily, and mortalities were recorded. LD50 value was estimated by the dose-response curve at 24 and 48 h post injection using Probit analysis in SPSS Statistics. The procedure was performed at the University of Crete which has licensed designated facilities for experimentation with animals (registration number: EL-BIOexp-10) and the protocol was approved by the General Directorate of Regional Agricultural Economy and Veterinary Services of the Region of Crete (License number: 147115/17-07-2017).

4. Discussion

Aeromonas veronii was isolated from diseased European seabass farmed in seven localities in both West and East Aegean Sea. The species was the most prevalent in all incidents of

Aeromonas-suspected infections with key clinical signs lethargy, icteric appearance and petechial hemorrhages externally, splenomegaly and nodules on spleen and kidney internally, as initially described [

9]. To our knowledge this is the first study after the description of the disease that directly correlates this pathology of seabass with

A. veronii in a large geographic area. The study aimed to record and describe the variability of the pathogen in the affected areas and set the basis for the disease’s management in the future. Comparative analysis was conducted on different features of the pathogen.

Aeromonas veronii was the most prevalent species in all incidents of

Aeromonas infections in seabass in both sides of the Aegean Sea (West/East). In the case of fish farm 1 (West) where the disease was initially described [

9] we can now talk for an established problem as long as

A. veronii was isolated from diseased fish almost all year round (March–December) excluding the winter months (temperature <18 °C), over the past ten years. Regarding the West Aegean Sea, while initially the disease was reported to affect only two neighboring fish farms in Argolikos Bay, it has now affected one more farm in the same area but more importantly it has geographically expanded to the neighboring Saronikos Bay where aquaculture activity is very intensive.

In the East Aegean Sea, the situation appeared less persistent. Reports for aeromonad outbreaks were not constant in time. Outbreaks also occurred during the summer months. Fish exhibiting the typical clinical signs of

A. veronii disease are still present in the field in summer months (personal communications with fish farmers) but are not considered a threat for the moment because impacts are much lower than those recorded in the West Aegean Sea. Nevertheless, a recent outbreak in Bodrum (sampling 24) and the similarities of strain T04-D with the rest of eastern isolates should be considered when discussing the disease’s occurrence in East Aegean Sea. In any case, the ability to cause hemolysis in seabass blood agar was observed in all tested isolates, an attribute related to the hepatic jaundice and the icteric appearance of the diseased fish in the field but also to the in vivo hemolysis observed in seabass challenged with strains NS and PDB [

9]. Pathogenicity tests in zebrafish showed similar virulence ability for all the strains. However, it should be noted that virulence in seabass is much higher following intraperitoneal injection with doses as low as 10

4 cfu per fish resulting in 100% mortality within 48 h. This together with the fact that other fish species cultured in adjacent cages are not affected during disease outbreaks suggests either an adaptation of the pathogen to this host, or an increase sensitivity of seabass to

A. veronii. This should be further investigated in future studies.

The same species (

A. veronii bv.

sobria) has been reported in diseased seabass and seabream in Italy [

27], and from diseased seabass in one more case in the Black Sea [

41]. In the latter, the bacterium was reported as the most prevalent species in diseased seabass, isolated alone, or in mixed-infections with

Ph. damselae subsp.

damselae and

Vibrio spp. The sampling was conducted during summer and autumn in water temperature between 20–26 °C, in the same range with the outbreaks in the Aegean Sea.

A. veronii has also been reported in diseased rainbow trout farmed in the Black Sea and in the Aegean Sea [

42]. Fish transfers between farms located in the Black Sea and the Aegean regions could explain the establishment of the pathogen in the latter, however this should be confirmed in a future study using molecular epidemiological methods.

Three phenotypic groups can be described based on motility and pigment production: a) The West Aegean Sea, rarely isolated strains non-motile, non-pigment producing, b) the West Aegean Sea strains motile and pigment-producing, and c) the East Aegean Sea isolates motile and I-pigment-producing. Typical biochemical properties of

Aeromonas spp., similar to positive catalase and oxidase reactions, inability to produce acid from xylose, absence of urease, and fermentation of D-glucose were evident for all isolates from seabass [

43]. Production of acid from D-arabitol was evident for 47/50 isolates, only few grew in salinity over 4% NaCl, while trehalose fermentation was evident mainly for the western ones. Despite the lack of motility (NS and NS 13), pigment production (western isolates), and negative indole reaction (all seabass isolates) that are characteristics of

A. salmonicida [

44], all seabass isolates were negative for fermentation of L-arabinose and salicin which are characteristics of the

A. sobria species complex [

43]. In the

A. sobria species complex, sucrose fermentation (all isolates) is characteristic for

A. veronii and among the species’ biovarieties negative ODC reaction (all except for BIOO50A) is characteristic of

A. veronii bv.

sobria [

43,

45]. It is worth mentioning that indole negative

A. veronii was reported in both cases of occurrence of the species in diseased seabass mentioned before; in Italy (strains Ae4 and Ae59) [

27], and in the Black Sea [

41]. Few pigment-producing isolates of

A. veronii were also reported in [

27]. The brown pigment produced by western strains seems to be pyomelanin which is produced by the tyrosine metabolism pathway [

46]. The mechanism of pyomelanin production as well as its importance as competitive advantage [

47] for

A. veronii is the subject of a parallel study of our group (manuscript in preparation).

Biochemically, the only common characteristic among seabass strains was the negative indole reaction which was also evident in other studies [

27,

41]. Whether this is an adaptation that gives advantage to these

A. veronii strains compared to other aeromonads or other common marine pathogens, has to be investigated as long as indole has been correlated to key aspects of bacterial physiology like drug resistance, biofilm formation, and virulence [

48]. For example, non-indole-producing bacteria use diverse oxygenases, which degrade indole from other species producing derivatives implicated in bacterial competition [

48].

The resistance to ampicillin (penicillins) together with first generation cephalosporins is genetically encoded in aeromonads [

49]. Two beta-lactamase genes were found in the genomes that could justify the ampicillin-resistant phenotype. However, the seabass strains studied here were susceptible to all the other registered for use in aquaculture antibiotics tested. Acquired resistance to antibiotics, e.g., tetracycline, oxolinic acid and flumequine has been reported in aeromonads in aquaculture systems [

50,

51]. Thus, one assumption would be that the multiple susceptibility detected here for

A. veronii indicates a relatively recent appearance of the species in the Aegean Sea or a more rationale use of antibiotics according to the best practices in the Greek aquaculture industry. In any case, the species has been reported in seabass approximately in the last decade.

Regardless of the phenotypic divergence and the West/East pattern of biochemical diversification shown in cluster analysis, the western-eastern seabass isolates were almost indistinguishable by the majority of the genetic markers used for identification. This was also seen in the phylogenetic analyses in which the strain Ae4 isolated from diseased seabass in Italy showed 0% divergence from the seabass isolates in the Aegean Sea while strain, e.g., XU 1 from

X. helleri was distinct. At the genomic level, high genomic similarity was observed as shown from Ortho-ANI values. The SNPs analysis was consistent with the patterns of phenotypic and geographic origin diversification. Despite the difference in isolation time, the non-motile, non-pigment producing western strains were closer to each other compared with the motile, pigment-producing ones. The same was evident also for the eastern strains (motile, non-pigment producing). The West/East pattern was clearly demonstrated as the difference among strains of different areas that was at least one order of magnitude higher than among strains of the same area. Divergence among

A. veronii seabass isolates were also at least one order of magnitude higher than the ones reported in

A. salmonicida subsp.

salmonicida isolated from fresh and seawater farms of trout in Denmark which had a time gap of isolation of approximately 30 years [

30].

While for

A. salmonicida, host related homogeneity among subpopulations of strains has been proposed in various cases using different methodologies [

52], the situation described for

A. veronii here might be more complicated as also reported elsewhere [

53]. Despite the fact that the particular strains of the species affected only seabass and not seabream nor other species farmed in neighboring cages [

9], zebrafish was a successful model for the pathogenicity assay as long as mortality reached 100% within 48 h post challenge, at higher, however, doses from the respective needed for seabass [

9]. High genomic similarity as observed here has been reported for virulent strains of

A. hydrophila of the same ST which showed 99.81%–100% similarity in ANI values despite their distant geographic origin (USA, China), isolation source (fish and soil) and time of isolation (1989–2010) [

54]. Furthermore, the divergence among western-eastern isolates through SNPs analysis is suggestive of independent evolutionary routes of the pathogen in the two sides of the Aegean Sea at least for the last decade that have been detected and isolated. Whether there is a common indole negative ancestor, or this is a case of convergent evolution with adaptive advantage for the pathogen to a new environment, e.g., marine environment, needs further investigation. It should be noted that pathogenic mesophilic aeromonads are mostly found in environments of lower salinity. Additionally, the host range of the pathogen is not defined yet and host physiology should be taken under consideration for possible vulnerability to bacterial pathogens or groups of pathogenic taxa.

The outer membrane proteins were studied as long as they are related to virulence and pathogenicity involving in the attachment and invasion of bacteria to the host. Many known OMPs have been tested as vaccine candidates as they have strong immunogenic effects. The outer membrane protein W has been shown to be highly conserved among

Aeromonas spp. but has also homology with the OmpW of other taxa [

55]. Common carp (

Cyprinus carpio) intraperitoneally vaccinated and rohu (

Labeo rohita) orally vaccinated with recombinant OmpW from

A. hydrophila produced antibody titers and showed higher relative percent survival (RPS%) compared to the control groups following challenge tests [

56,

57]. Recombinant protein OmpC (general porin family), from

A. hydrophila induced immune response in mice [

58]. The porin CDS-2 from strain VCK 1 showed 84% similarity in gene sequence (HF546053) and 87% similarity with protein OmpC of

A. hydrophila (EUS112) [

58]. Both OmpW and OmpC were highly conserved among the seabass isolates and therefore could be considered as good candidates for vaccine development.

Other highly conserved membrane proteins among seabass isolates were the porins OmpA which are members of the well-studied OmpA protein family with key role in bacterial pathogenicity [

59]. In

A. veronii from the intestinal tract of carp, two tandem homologues (OmpAI and OmpAII) have been reported and the proteins were related to adhesion of the bacterium to the surface of the intestinal tract of common carp [

60]. Here, these homologues corresponded to OmpA porins CDS-1 and CDS-2 and were found tandem with a third homologue (hypothetical CDS-8) with total protein similarity in this group of three homologues >50%. Comparison with sequences reported from carp (AB290200), OmpAI showed 92% similarity to OmpA porin-2 while OmpAII 99% similarity to OmpA porin-1 from seabass. This was the highest similarity of OmpAI and OmpAII from carp when comparing to the other seabass homologues of OmpA-porins. An oral recombinant vaccine with

Lactobacillus casei expressing the OmpAI induced immune response and protection against challenge with

A. veronii in common carp [

61].

Few outer membrane proteins varied significantly among seabass isolates in the two sides of the Aegean like maltoporin LamB and S-layer. Both of these membrane substances have been studied and are capable to induce immune response and protection in fish [

62,

63,

64]. Whether these differences are significant in the development of an

A. veronii vaccine for seabass has to be further investigated. In terms of strain selection for the development of a bacterin vaccine for the Aegean Sea, a bivalent preparation containing eastern and western strains would be worth trying. Protein distances among seabass strains and strains B565 and XU 1 indicated that at least some proteins were highly conserved among them. This should be further investigated including more

A. veronii genomes from different hosts and isolation sources in order to detect for instance possible host-related similarities or highly conserved proteins that could serve as antigens for recombinant vaccines for

A. veronii.

The coverage of the GIs in the genomes of the seabass strains (>10%) laid in the higher part of the range described for marine bacteria (3%–12%) [

65] where in the 50% of the studied genomes the GI coverage was approximately 3%. Mobile elements are important for bacterial evolution as they often hand in virulence factors and fitness features. Preliminary analysis detected virulence factors similar to the genes of the type III secretion system in the seabass’ GIs as described elsewhere [

66]. In addition, the analogy of prophages per genome detected in the current study, although not intact, is mentioned before in another species of the genus,

A hydrophila [

54,

67,

68]. Prophage genes are widely distributed within the aeromonads [

69,

70], but in the course of evolution there is a constant process of losing and acquiring such genetic material. Further analysis is needed in order to study the relationship among GIs’ size and composition and prophage occurrence to the pathogenicity of the

A. veronii studied herein.

One of our aims was to clarify if the phenotypic variability of the strains that is the presence and absence of the polar flagellum imposed a difference in the virulence of the bacteria. The non-motile strains had slightly lower LD50, when intraperitoneally injected, which can be due to the fact that the lack of flagella favors them. The flagella are major antigenic elements and the presence of both flagellated and non-flagellated bacteria within a species and also the switch from the one state to the other happens to pathogens and environmental isolates [

71,

72]. The flagella are strictly regulated structures and they are not formed or do not function if one of the motility genes is missing [

73,

74] or is non-functional [

75]. Between the four genes that differed among the strains, the

flgT is more important for the stability and the secretion of the flagellum. The mutants of

A. hydrophila with

flgT gene deleted had no flagellum [

76] contrary to the deletion of the

fliS that resulted in phenotypes with reduced motility in

Y. pseudotuberculosis [

77].

The type II and III secretion systems, prominent structures for the protein transport through the cell envelope, were conserved in all nine strains. There were three clusters of genes of the T3SS and one of the T2SS, containing the components of the apparatuses. The T3SS is considered key factor for the infection mechanism of

A veronii bv.

sobria [

78]. Its function is linked to the resistance of the bacteria to the immune response of the host [

79]. In addition, the T2SS participates in the translocation of toxins and assemblage of the type IV pili in the outer membrane [

80]. The type VI secretion system was not detected in the strains of West Aegean Sea and the lack of the cluster was a considerable difference. The system is significant for intrabacterial communication and competition but it is also a dominance mechanism within the gut environment [

81,

82,

83]. However, its absence has been reported again in pathogens of the genus [

54,

84] and in

Bacteroides fragilis the presence of the system varied among strains occupying the same niche [

81], which is similar to our case. To sum up, it seems that the first two functional secretion systems are more crucial than the lack of the latter, considering that the strains caused similar pathogenicity in the in vivo studies.

Other genes detected are a set of common exotoxins for aeromonads, including hemolytic enzymes, and iron-binding and transport genes. The

A. veronii strains exhibit intense hemolytic activity and they are adapted to fish blood causing greater hemolytic effect than in mammal blood, as shown in the previous study [

9]. There are many related genes inbuilt in the genome of the strains similar to hemolysins, hemagglutins, the TonB-ExbB-ExbD iron-binding transport system, and iron uptake regulation genes such as the FUR transcriptional factor that justify their virulence. An important difference in the strains of West Aegean Sea compared to the East Aegean ones, is that they have two fragments of aerolysin family toxin due to the presence of an integrase. Aerolysin is responsible for the total osmotic lysis of blood cells and is a major virulence factor of the species. In a recent study of

A. veronii, the deletion of aerolysin resulted in a rapid loss of virulence of the pathogen and increased survival of the challenged animals [

6]. In our study, in vivo virulence using zebrafish as a model is similar, however results from the field suggest that the West Aegean Sea isolates cause significantly higher mortalities to the cultured seabass.