Evolution of Translational Machinery in Fast- and Slow-Growing Bacteria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

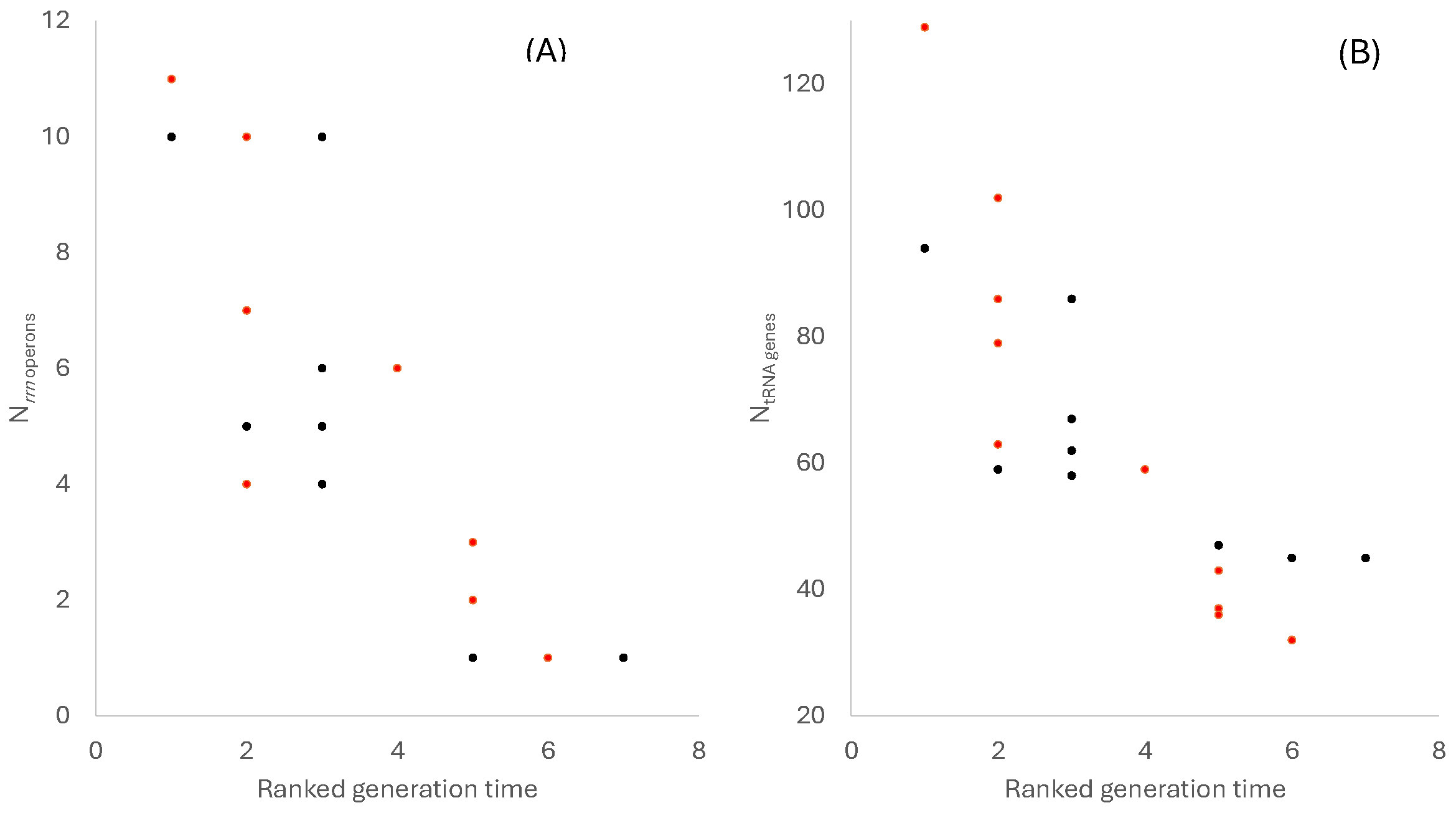

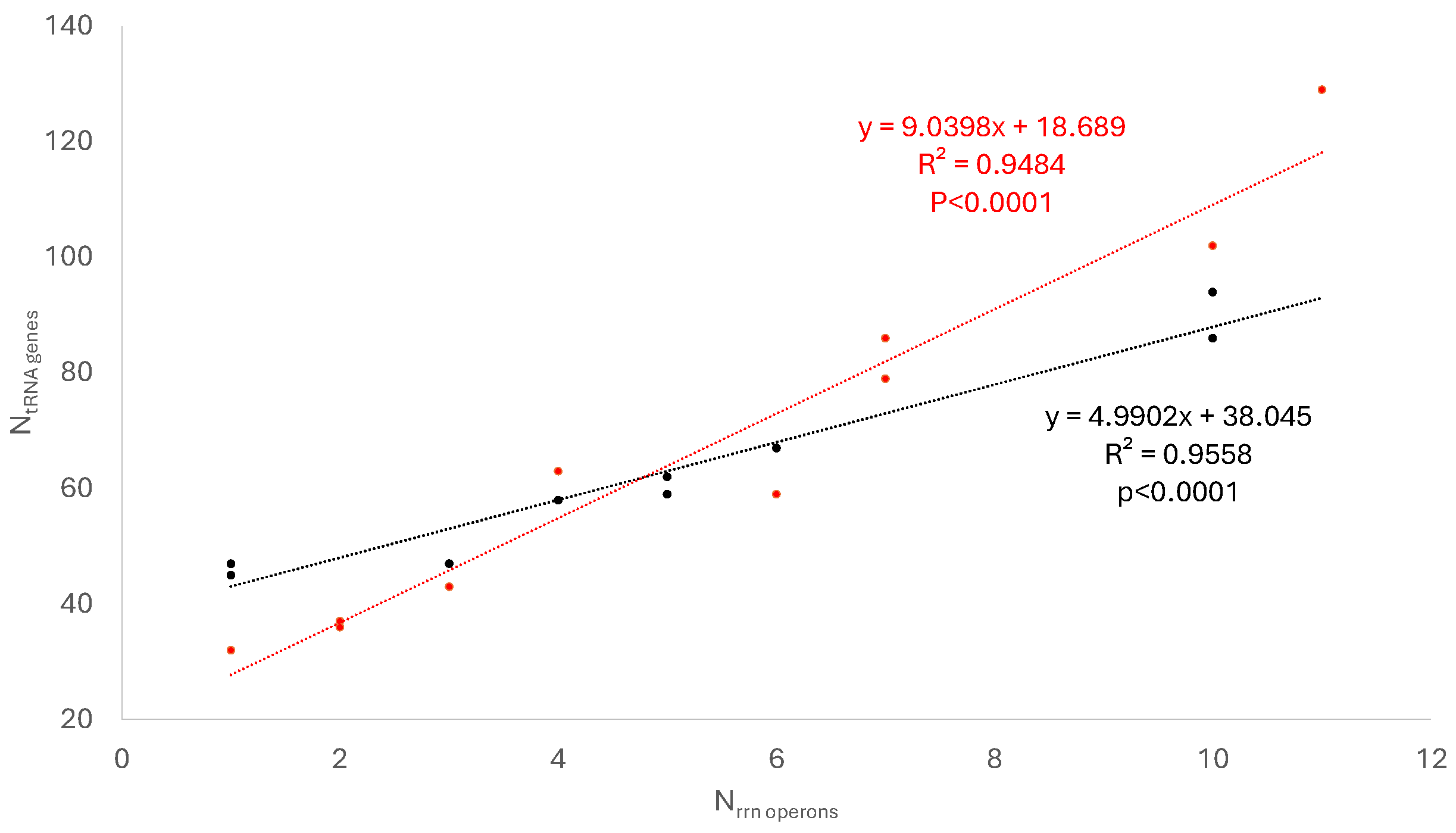

3.1. The Number of rrn Operons and tRNA Genes Decreases with Doubling Time

3.2. Association Between tRNA Genes and Amino Acid Usage

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimizing Selection on Bacterial Translation Machinery

4.2. What Is the Optimal Number of tRNAs per Ribosome?

4.3. Why Do Some Bacteria Invest So Little in Translation Machinery?

4.4. The Number of tRNA Genes May Not Reflect Cytoplasmic tRNA Abundance

4.5. Complications in Lifestyle

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eagon, R.G. Pseudomonas natriegens, a marine bacterium with a generation time of less than 10 minutes. J. Bacteriol. 1962, 83, 736–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Ye, B.; Jin, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Shen, W.; et al. Changes in Vibrio natriegens Growth Under Simulated Microgravity. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.T. Comparative and functional genomics of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Microbiology 2002, 148, 2919–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Dai, X. On the intrinsic constraint of bacterial growth rate: M. tuberculosis’s view of the protein translation capacity. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengenbacher, M.; Kaufmann, S.H. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Success through dormancy. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. How optimized is the translational machinery in Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and Saccharomyces cerevisiae? Genetics 1998, 149, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X. A Major Controversy in Codon-Anticodon Adaptation Resolved by a New Codon Usage Index. Genetics 2015, 199, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudla, G.; Murray, A.W.; Tollervey, D.; Plotkin, J.B. Coding-Sequence Determinants of Gene Expression in Escherichia coli. Science 2009, 324, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuller, T.; Waldman, Y.Y.; Kupiec, M.; Ruppin, E. Translation efficiency is determined by both codon bias and folding energy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 3645–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, R.; Chithambaram, S.; Xia, X. Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus phages: Effect of translation initiation efficiency on differential codon adaptation mediated by virulent and temperate lifestyles. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithambaram, S.; Prabhakaran, R.; Xia, X. Differential Codon Adaptation between dsDNA and ssDNA Phages in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithambaram, S.; Prabhakaran, R.; Xia, X. The Effect of Mutation and Selection on Codon Adaptation in Escherichia coli Bacteriophage. Genetics 2014, 197, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausing, K. Regulation of ribosome production in Escherichia coli: Synthesis and stability of ribosomal RNA and of ribosomal protein messenger RNA at different growth rates. J. Mol. Biol. 1977, 115, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Sampla, A.K.; Tyagi, J.S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis rrn promoters: Differential usage and growth rate-dependent control. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 4326–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, H.; Dennis, P. Modulation of chemical composition and other parameters of the cell by growth rate. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and molecular biology. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, 2nd ed.; Neidhardt, F.C., Ed.; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 1553–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Valgepea, K.; Adamberg, K.; Seiman, A.; Vilu, R. Escherichia coli achieves faster growth by increasing catalytic and translation rates of proteins. Mol. Biosyst. 2013, 9, 2344–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazyrina, J.; Materne, E.M.; Dreher, T.; Storm, D.; Junne, S.; Adams, T.; Greller, G.; Neubauer, P. High cell density cultivation and recombinant protein production with Escherichia coli in a rocking-motion-type bioreactor. Microb. Cell Fact. 2010, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milo, R. What is the total number of protein molecules per cell volume? A call to rethink some published values. Bioessays 2013, 35, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, H.; Chikamatsu, K.; Aono, A.; Murata, K.; Miyazaki, N.; Kayama, Y.; Bhatt, A.; Fujiwara, N.; Maeda, S.; Mitarai, S. Fundamental Cell Morphologies Examined with Cryo-TEM of the Species in the Novel Five Genera Robustly Correlate with New Classification in Family Mycobacteriaceae. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 562395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farookhi, H.; Xia, X. Differential Selection for Translation Efficiency Shapes Translation Machineries in Bacterial Species. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X. The cost of wobble translation in fungal mitochondrial genomes: Integration of two traditional hypotheses. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Engels, B. The protonation state of catalytic residues in the resting state of KasA revisited: Detailed mechanism for the activation of KasA by its own substrate. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nataraj, V.; Varela, C.; Javid, A.; Singh, A.; Besra, G.S.; Bhatt, A. Mycolic acids: Deciphering and targeting the Achilles’ heel of the tubercle bacillus. Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 98, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Siddiqui, S.; Shang, S.; Bian, Y.; Bagchi, S.; He, Y.; Wang, C.R. Mycolic acid-specific T cells protect against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a humanized transgenic mouse model. eLife 2015, 4, e08525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, E.; Alon, U. Optimality and evolutionary tuning of the expression level of a protein. Nature 2005, 436, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with extensive resistance to second-line drugs—worldwide, 2000–2004. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2006, 55, 301–305. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, N.R.; Moll, A.; Sturm, A.W.; Pawinski, R.; Govender, T.; Lalloo, U.; Zeller, K.; Andrews, J.; Friedland, G. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis as a cause of death in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV in a rural area of South Africa. Lancet 2006, 368, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong, Y.E.A.; Phelan, J.; Perdigão, J.; Machado, D.; Miranda, A.; Portugal, I.; Viveiros, M.; Clark, T.G.; Hibberd, M.L. Genome-wide analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymorphisms reveals lineage-specific associations with drug resistance. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udwadia, Z.F.; Amale, R.A.; Ajbani, K.K.; Rodrigues, C. Totally drug-resistant tuberculosis in India. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velayati, A.A.; Masjedi, M.R.; Farnia, P.; Tabarsi, P.; Ghanavi, J.; ZiaZarifi, A.H.; Hoffner, S.E. Emergence of new forms of totally drug-resistant tuberculosis bacilli: Super extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis or totally drug-resistant strains in Iran. Chest 2009, 136, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. Horizontal Gene Transfer and Drug Resistance Involving Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, E.L.; Flugga, N.; Boer, J.L.; Mulrooney, S.B.; Hausinger, R.P. Interplay of metal ions and urease. Met. Integr. Biometal Sci. 2009, 1, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.C.; Oh, S.T.; Sung, J.Y.; Cha, K.A.; Lee, M.H.; Oh, B.H. Supramolecular assembly and acid resistance of Helicobacter pylori urease. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001, 8, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, H.L.; Island, M.D.; Hausinger, R.P. Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 59, 451–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, H.L.; Hu, L.T.; Foxal, P.A. Helicobacter pylori urease: Properties and role in pathogenesis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1991, 187, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, G.; Weeks, D.L.; Melchers, K.; Scott, D.R. The gastric biology of Helicobacter pylori. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003, 65, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stingl, K.; Altendorf, K.; Bakker, E.P. Acid survival of Helicobacter pylori: How does urease activity trigger cytoplasmic pH homeostasis? Trends Microbiol. 2002, 10, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rektorschek, M.; Buhmann, A.; Weeks, D.; Schwan, D.; Bensch, K.W.; Eskandari, S.; Scott, D.; Sachs, G.; Melchers, K. Acid resistance of Helicobacter pylori depends on the UreI membrane protein and an inner membrane proton barrier. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 36, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X. Multiple regulatory mechanisms for pH homeostasis in the gastric pathogen, Helicobacter pylori. Adv. Genet. 2022, 109, 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Behura, S.K.; Severson, D.W. Coadaptation of isoacceptor tRNA genes and codon usage bias for translation efficiency in Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol. Biol. 2011, 20, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. Bioinformatics and Translation Elongation. In Bioinformatics and the Cell: Modern Computational Approaches in Genomics, Proteomics and Transcriptomics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 197–238. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Paredes-Sabja, D.; Sarker, M.R.; McClane, B.A. Clostridium perfringens Sporulation and Sporulation-Associated Toxin Production. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, E.C.D. Foodborne Diseases: Overview of Biological Hazards and Foodborne Diseases. In Encyclopedia of Food Safety; Motarjemi, Y., Ed.; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas, D.M.; Schneewind, O. Growth and laboratory maintenance of Staphylococcus aureus. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2013, 28, 9C.1.1–9C.1.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, M.E.; Hauser, P.M.; Sharpe, R.G.; Errington, J. Bacillus subtilis cell cycle as studied by fluorescence microscopy: Constancy of cell length at initiation of DNA replication and evidence for active nucleoid partitioning. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, P.M.; Täuber, M.G.; Hackbarth, C.J.; Sande, M.A. Influence of body temperature on bacterial growth rates in experimental pneumococcal meningitis in rabbits. Infect. Immun. 1986, 52, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.S.; D’Orazio, S.E.F. Listeria monocytogenes: Cultivation and laboratory maintenance. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2013, 31, 9b.2.1–9b.2.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.; Chikindas, M.L. Listeria: A foodborne pathogen that knows how to survive. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 113, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śliżewska, K.; Chlebicz-Wójcik, A. Growth Kinetics of Probiotic Lactobacillus Strains in the Alternative, Cost-Efficient Semi-Solid Fermentation Medium. Biology 2020, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsson, L. Lactic Acid Bacteria: Classification and Physiology. In Lactic Acid Bacteria: Microbiological and Functional Aspects; Salminen, S., von Wright, A., Ouwehand, A., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, G.M.; Berney, M.; Gebhard, S.; Heinemann, M.; Cox, R.A.; Danilchanka, O.; Niederweis, M. Physiology of mycobacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2009, 55, 81–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, M.A.; Nessar, R.; Singh, A.K. Laboratory maintenance of Mycobacterium abscessus. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2010, 18, 10D.1.1–10D.1.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Change, Y.T.; Andersen, R.N.; Vaituzis, Z. Growth of Mycobacterium lepraemurium in cultures of mouse peritoneal macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 1967, 93, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryselius, R.; Izutsu, K.; Honda, T.; Iida, T. Differential replication dynamics for large and small Vibrio chromosomes affect gene dosage, expression and location. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezonov, G.; Joseleau-Petit, D.; D’Ari, R. Escherichia coli physiology in Luria-Bertani broth. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 8746–8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Haagensen, J.A.; Jelsbak, L.; Johansen, H.K.; Sternberg, C.; Høiby, N.; Molin, S. In situ growth rates and biofilm development of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations in chronic lung infections. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 2767–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neidhardt, F.C.; Ingraham, J.L.; Schaechter, M. Physiology of the Bacterial Cell: A Molecular Approach; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.R.; Moraes, C.A.; Bessan, J.; Vanetti, M.C. Validation of a predictive model describing growth of Salmonella in enteral feeds. Braz. J. Microbiol. Publ. Braz. Soc. Microbiol. 2009, 40, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artman, M.; Domenech, E.; Weiner, M. Growth of Haemophilus influenzae in simulated blood cultures supplemented with hemin and NAD. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1983, 18, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R.J.; Marsh, J.W.; Humphrys, M.S.; Huston, W.M.; Myers, G.S.A. Early Transcriptional Landscapes of Chlamydia trachomatis-Infected Epithelial Cells at Single Cell Resolution. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Enciso, G.A.; Boassa, D.; Chander, C.N.; Lou, T.H.; Pairawan, S.S.; Guo, M.C.; Wan, F.Y.M.; Ellisman, M.H.; Sütterlin, C.; et al. Replication-dependent size reduction precedes differentiation in Chlamydia trachomatis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Doyle, M.P. Effect of environmental and substrate factors on survival and growth of Helicobacter pylori. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battersby, T.; Walsh, D.; Whyte, P.; Bolton, D.J. Campylobacter growth rates in four different matrices: Broiler caecal material, live birds, Bolton broth, and brain heart infusion broth. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2016, 6, 31217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.M.; Casjens, S.; Huang, W.M.; Sutton, G.G.; Clayton, R.; Lathigra, R.; White, O.; Ketchum, K.A.; Dodson, R.; Hickey, E.K.; et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 1997, 390, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heroldová, M.; Němec, M.; Hubálek, Z. Growth parameters of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto at various temperatures. Zentralblatt Für Bakteriol. 1998, 288, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. DAMBE7: New and improved tools for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1550–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutscher, M.P. Twenty years of bacterial RNases and RNA processing: How we’ve matured. RNA 2015, 21, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keener, J.; Nomura, M. Regulation of ribosome synthesis. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology; Neidhardt, F.C., Curtiss, R., III, Ingraham, J.L., Lin, E.C.C., Low, K.B., Magasanik, B., Reznikoff, W.S., Riley, M., Schaechter, M., Umbarger, J.E., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; Volume 1, pp. 1417–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, H.D.; Appleman, J.A.; Gourse, R.L. Regulation of the Escherichia coli rrnB P2 promoter. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Gourse, R.; Baughman, G. Regulation of the synthesis of ribosomes and ribosomal components. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1984, 53, 75–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noller, H.F. Evolution of Protein Synthesis from an RNA World. In RNA World: From Life’s Origin to Diversity in Gene Regulation; Atkins, J.F., Gesteland, R.F., Cech, T.R., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima, H.; Fukuchi, S.; Nishikawa, K. Compositional changes in RNA, DNA and proteins for bacterial adaptation to higher and lower temperatures. J. Biochem. 2003, 133, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.-Z.; Wei, W.; Qin, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, A.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Guo, F.-B. Co-adaption of tRNA gene copy number and amino acid usage influences translation rates in three life domains. DNA Res. 2017, 24, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, A.; Otaka, E.; Osawa, S. Protein synthesis in a relaxed-control mutant of Escherichia coli upon recovery from methionine starvation. J. Mol. Biol. 1966, 19, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunschede, H.; Bremer, H. Synthesis and breakdown of proteins in Escherichia coli during amino-acid starvation. J. Mol. Biol. 1971, 57, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shine, J.; Dalgarno, L. The 3′-terminal sequence of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA: Complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shine, J.; Dalgarno, L. Identical 3′-terminal octanucleotide sequence in 18S ribosomal ribonucleic acid from different eukaryotes. A proposed role for this sequence in the recognition of terminator codons. Biochem. J. 1974, 141, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shine, J.; Dalgarno, L. Determinant of cistron specificity in bacterial ribosomes. Nature 1975, 254, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, A.; de Boer, H.A. Specialized ribosome system: Preferential translation of a single mRNA species by a subpopulation of mutated ribosomes in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 4762–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steitz, J.A.; Jakes, K. How ribosomes select initiator regions in mRNA: Base pair formation between the 3′ terminus of 16S rRNA and the mRNA during initiation of protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 4734–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, T.; Weissmann, C. Inhibition of Qbeta RNA 70S ribosome initiation complex formation by an oligonucleotide complementary to the 3′ terminal region of E. coli 16S ribosomal RNA. Nature 1978, 275, 770–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Evaluation of the “scanning model” for initiation of protein synthesis in eucaryotes. Cell 1980, 22, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Mechanism of mRNA recognition by eukaryotic ribosomes during initiation of protein synthesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1981, 93, 81–123. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X. Optimizing Protein Production in Therapeutic Phages against a Bacterial Pathogen, Mycobacterium abscessus. Drugs Drug Candidates 2023, 2, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. Bioinformatics and Translation Initiation. In Bioinformatics and the Cell: Modern Computational Approaches in Genomics, Proteomics and Transcriptomics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Dalboge, H.; Carlsen, S.; Jensen, E.B.; Christensen, T.; Dahl, H.H. Expression of recombinant growth hormone in Escherichia coli: Effect of the region between the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and the ATG initiation codon. DNA 1988, 7, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.; Lilley, R.; Little, S.; Emtage, J.S.; Yarranton, G.; Stephens, P.; Millican, A.; Eaton, M.; Humphreys, G. Codon usage can affect efficiency of translation of genes in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984, 12, 6663–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, M.A.; Kurland, C.G.; Pedersen, S. Codon usage determines translation rate in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1989, 207, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, D.I.; Bohman, K.; Isaksson, L.A.; Kurland, C.G. Translation rates and misreading characteristics of rpsD mutants in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1982, 187, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, S.G.; Buckingham, R.H.; Kurland, C.G. Does codon composition influence ribosome function? Embo J. 1984, 3, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.G.; Kurland, C.G. Codon preferences in free-living microorganisms. Microbiol. Rev. 1990, 54, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, J.; Park, E.-C.; Seed, B. Codon usage limitation in the expression of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Curr. Biol. 1996, 6, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngumbela, K.C.; Ryan, K.P.; Sivamurthy, R.; Brockman, M.A.; Gandhi, R.T.; Bhardwaj, N.; Kavanagh, D.G. Quantitative Effect of Suboptimal Codon Usage on Translational Efficiency of mRNA Encoding HIV-1 gag in Intact T Cells. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. Detailed Dissection and Critical Evaluation of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA Vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. Bioinformatics and Translation Termination in Bacteria. In Bioinformatics and the Cell: Modern Computational Approaches in Genomics, Proteomics and Transcriptomics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Varenne, S.; Buc, J.; Lloubes, R.; Lazdunski, C. Translation is a non-uniform process. Effect of tRNA availability on the rate of elongation of nascent polypeptide chains. J. Mol. Biol. 1984, 180, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavancy, G.; Garel, J.P. Does quantitative tRNA adaptation to codon content in mRNA optimize the ribosomal translation efficiency? Proposal for a translation system model. Biochimie 1981, 63, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikemura, T. Correlation between the abundance of Escherichia coli transfer RNAs and the occurrence of the respective codons in its protein genes. J. Mol. Biol. 1981, 146, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikemura, T. Correlation between the abundance of yeast transfer RNAs and the occurrence of the respective codons in protein genes. Differences in synonymous codon choice patterns of yeast and Escherichia coli with reference to the abundance of isoaccepting transfer RNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 1982, 158, 573–597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ikemura, T. Codon usage and tRNA content in unicellular and multicellular organisms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1985, 2, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; von der Haar, T. The architecture of eukaryotic translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 10098–10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, N.; Nikaido, H.; Bloom, B. Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Protection and Control; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Nagamani, S.; Sastry, G.N. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Cell Wall Permeability Model Generation Using Chemoinformatics and Machine Learning Approaches. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 17472–17482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarlier, V.; Nikaido, H. Permeability barrier to hydrophilic solutes in Mycobacterium chelonei. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarathy, J.P.; Dartois, V.; Lee, E.J. The role of transport mechanisms in mycobacterium tuberculosis drug resistance and tolerance. Pharmaceuticals 2012, 5, 1210–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, S.F.; Lenski, R.E. Evolution experiments with microorganisms: The dynamics and genetic bases of adaptation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colangeli, R.; Arcus, V.L.; Cursons, R.T.; Ruthe, A.; Karalus, N.; Coley, K.; Manning, S.D.; Kim, S.; Marchiano, E.; Alland, D. Whole genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals slow growth and low mutation rates during latent infections in humans. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.P.S.; Guan, X.L. Metabolic Versatility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during Infection and Dormancy. Metabolites 2021, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comín, J.; Cebollada, A.; Iglesias, M.J.; Ibarz, D.; Viñuelas, J.; Torres, L.; Sahagún, J.; Lafoz, M.C.; Esteban de Juanas, F.; Malo, M.C.; et al. Estimation of the mutation rate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cases with recurrent tuberculosis using whole genome sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16728, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, J.; Steyn, L.M. A ribosomal gene mutation in streptomycin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 167, 1505–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honoré, N.; Marchal, G.; Cole, S.T. Novel mutation in 16S rRNA associated with streptomycin dependence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, B.W.; Williams, A.; Marsh, P.D. The physiology and pathogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis grown under controlled conditions in a defined medium. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hani, J.; Feldmann, H. tRNA genes and retroelements in the yeast genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.G. Enjoy the Silence: Nearly Half of Human tRNA Genes Are Silent. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2019, 13, 1177932219868454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Silke, J.R.; Xia, X. An improved estimation of tRNA expression to better elucidate the coevolution between tRNA abundance and codon usage in bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X. Position weight matrix and Perceptron. In Bioinformatics and the Cell: Modern Computational Approaches in Genomics, Proteomics and Transcriptomics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Accession (1) | OGT (2) | GT (3) | Rank (4) | Ref. (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clostridium perfringens | NZ_CP065681 | 43 °C | ~7–15 min | 1 | [42,43] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | NC_007795 | 37 °C | ~21–35 min | 2 | [44] |

| Bacillus subtilis | NC_000964.3 | 37 °C | ~30–70 min | 3 | [45] |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | NZ_LN831051 | 37 °C | ~30–60 min | 3 | [46] |

| Listeria monocytogenes | NC_003210 | 37 °C | ~45–60 min | 3 | [47,48] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | NZ_CP028221 | 37 °C | ~50–70 min | 3 | [49,50] |

| Mycolicibacterium smegmatis | NZ_CP054795.1 | 37 °C | ~2 h | 5 | [51] |

| Mycobacterioides abscessus | NZ_CP034181.1 | 36 °C | ~4–5 h | 5 | [52] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | NC_000962.3 | 37 °C | ~20–30 h | 6 | [3,4,5] |

| M. leprae | NZ_CP029543.1 | 30 °C | ~7 days | 7 | [4,53] |

| Vibrio natriegens | NZ_CP009977, NZ_CP009978.1 | 37 °C | ~10 min | 1 | [1,2] |

| Vibrio cholerae | NZ_CP043554, NZ_CP043556.1 | 37 °C | ~16–20 min | 2 | [54] |

| Escherichia coli | NC_000913.3 | 37 °C | ~20–30 min | 2 | [55] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | NC_002516 | 37 °C | ~25–30 min | 2 | [56,57] |

| Salmonella enterica | NC_003197 | 37 °C | ~20–30 min | 2 | [57,58] |

| Haemophilus influenzae | NZ_CP007470.1 | 37 °C | ~103–107 min | 4 | [59] |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | NC_000117 | 35–37 °C | ~1.8–4.6 h | 5 | [60,61] |

| Helicobacter pylori | NZ_AP026446 | 37 °C | ~2.5–3 h | 5 | [62] |

| Campylobacter jejuni | NC_002163 | 42 °C | ~2–3 h | 5 | [63] |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | NZ_ABCW02000001 (6) | 33 °C | ~8.3–24 h | 6 | [64,65] |

| Model | α | β | γ | lnLmodel (1) | lnLnull (2) | p (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nrrn.Bacillati | 9.000380 | 0.011936 | −19.5164 | −25.8209 | 0.000384 | |

| Nrrn.Pseudomonadati | 8.863043 | 0.010691 | −18.9248 | −26.0992 | 0.000152 | |

| NtRNA.Bacillati | 51.377406 | 0.018713 | 45.392728 | −36.4670 | −151.0943 | 0.000000 |

| NtRNA.Pseudomonadati | 157.323365 | 0.056354 | 40.954750 | −131.4144 | −475.6256 | 0.000000 |

| Vibrio natriegens | Clostridium perfringens | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA (1) | N | CFS | MtRNA | N | CFS | MtRNA |

| A | 126,982 | 4 | 7 | 49,128 | 4 | 4 |

| C | 15,568 | 2 | 4 | 10,316 | 2 | 2 |

| D | 80,754 | 2 | 6 | 50,881 | 2 | 3 |

| E | 95,956 | 2 | 6 | 74,540 | 2 | 4 |

| F | 60,938 | 2 | 4 | 42,363 | 2 | 4 |

| G | 103,326 | 4 | 11 | 60,495 | 4 | 12 |

| H | 32,846 | 2 | 2 | 11,807 | 2 | 2 |

| I | 92,838 | 3 | 5 | 87,449 | 3 | 4 |

| K | 76,752 | 2 | 4 | 85,533 | 2 | 7 |

| L | 151,573 | 6 | 17 | 85,534 | 6 | 9 |

| N | 61,206 | 2 | 5 | 59,147 | 2 | 4 |

| P | 58,807 | 4 | 3 | 24,866 | 4 | 3 |

| Q | 64,988 | 2 | 6 | 18,015 | 2 | 3 |

| R | 65,549 | 6 | 11 | 30,389 | 6 | 7 |

| S | 97,945 | 6 | 7 | 56,898 | 6 | 5 |

| T | 79,535 | 4 | 7 | 42,052 | 4 | 5 |

| V | 107,453 | 4 | 6 | 59,549 | 4 | 4 |

| W | 18,772 | 1 | 2 | 6536 | 1 | 2 |

| Y | 44,625 | 2 | 6 | 36,940 | 2 | 3 |

| Taxon | DF | SS | MS | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | Model | 2 | 144.85534 | 72.42767 | 13.99081 | 0.00031 |

| Residual | 16 | 82.82887 | 5.17680 | |||

| Total | 18 | 227.68421 | ||||

| (B) | Model | 2 | 57.41445 | 28.70722 | 7.50306 | 0.00503 |

| Residual | 16 | 61.21713 | 3.82607 | |||

| Total | 18 | 118.63158 | ||||

| βi | SE | T | p | |||

| (A) | Intercept | −0.27790 | 1.34781 | −0.20619 | 0.83925 | |

| NAA | 0.00004 | 0.00002 | 2.17467 | 0.04500 | ||

| CFS | 1.04273 | 0.43905 | 2.37500 | 0.03039 | ||

| (B) | Intercept | 0.31282 | 1.19011 | 0.26285 | 0.79602 | |

| NAA | 0.00004 | 0.00002 | 2.23869 | 0.03974 | ||

| CFS | 0.72833 | 0.30624 | 2.37830 | 0.03019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xia, X. Evolution of Translational Machinery in Fast- and Slow-Growing Bacteria. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020377

Xia X. Evolution of Translational Machinery in Fast- and Slow-Growing Bacteria. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):377. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020377

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Xuhua. 2026. "Evolution of Translational Machinery in Fast- and Slow-Growing Bacteria" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020377

APA StyleXia, X. (2026). Evolution of Translational Machinery in Fast- and Slow-Growing Bacteria. Microorganisms, 14(2), 377. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020377