A Novel Bicistronic Adenovirus Vaccine Elicits Superior and Comprehensive Protection Against BVDV

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Mice

2.2. Cell Lines and Virus Culture

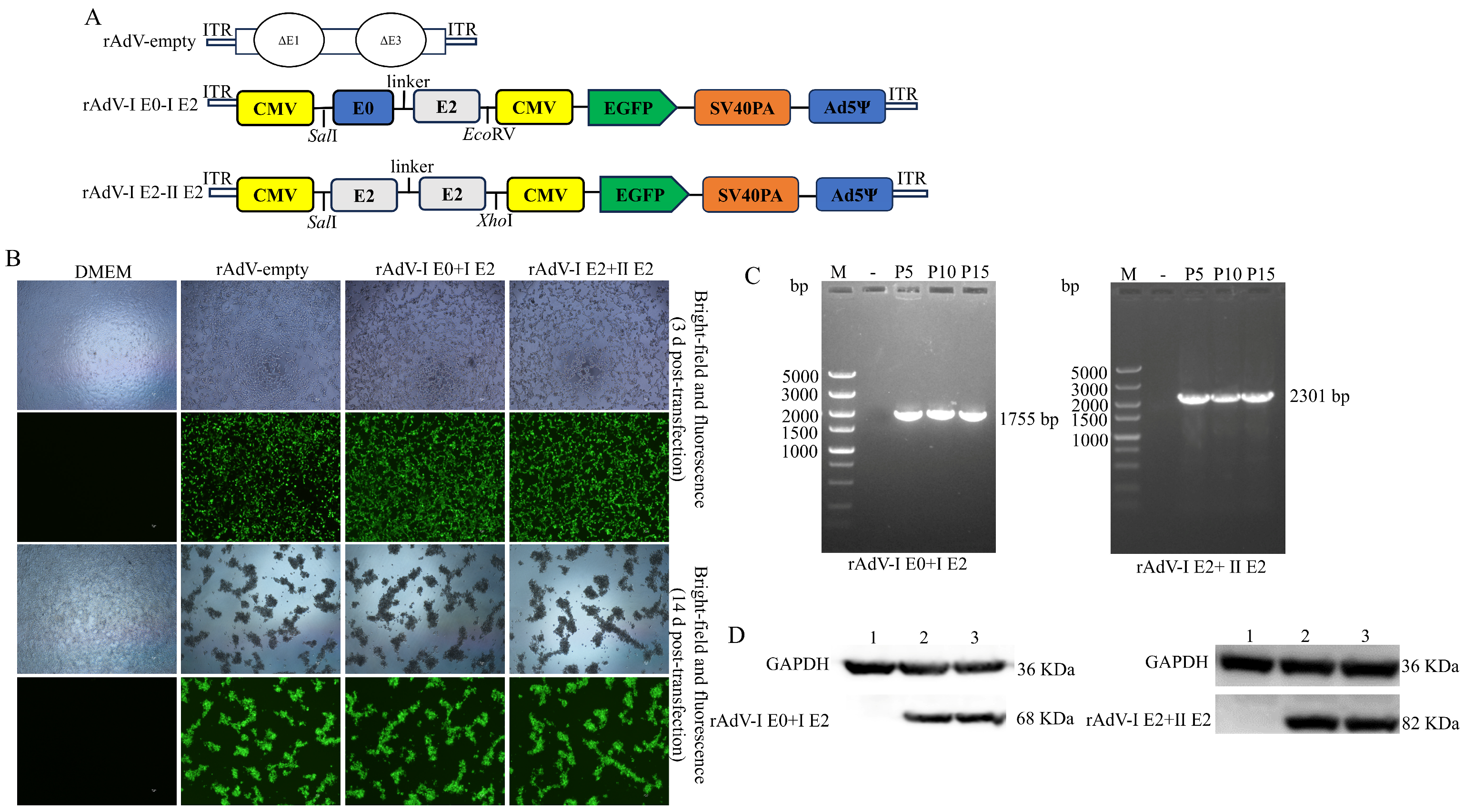

2.3. Construction and Characterization of rAdV-I E0+I E2 and rAdV-I E2+II E2

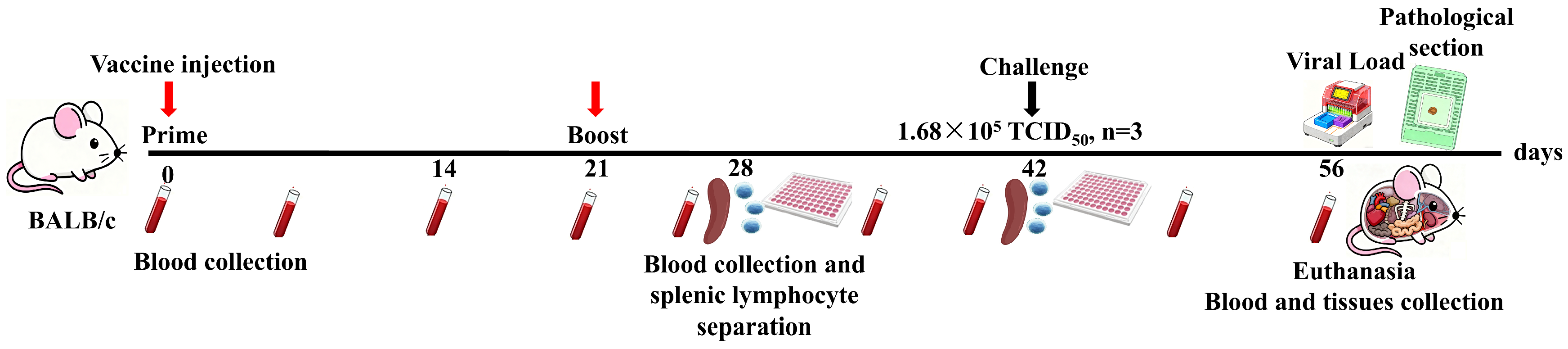

2.4. Vaccination Protocol and Sample Collection

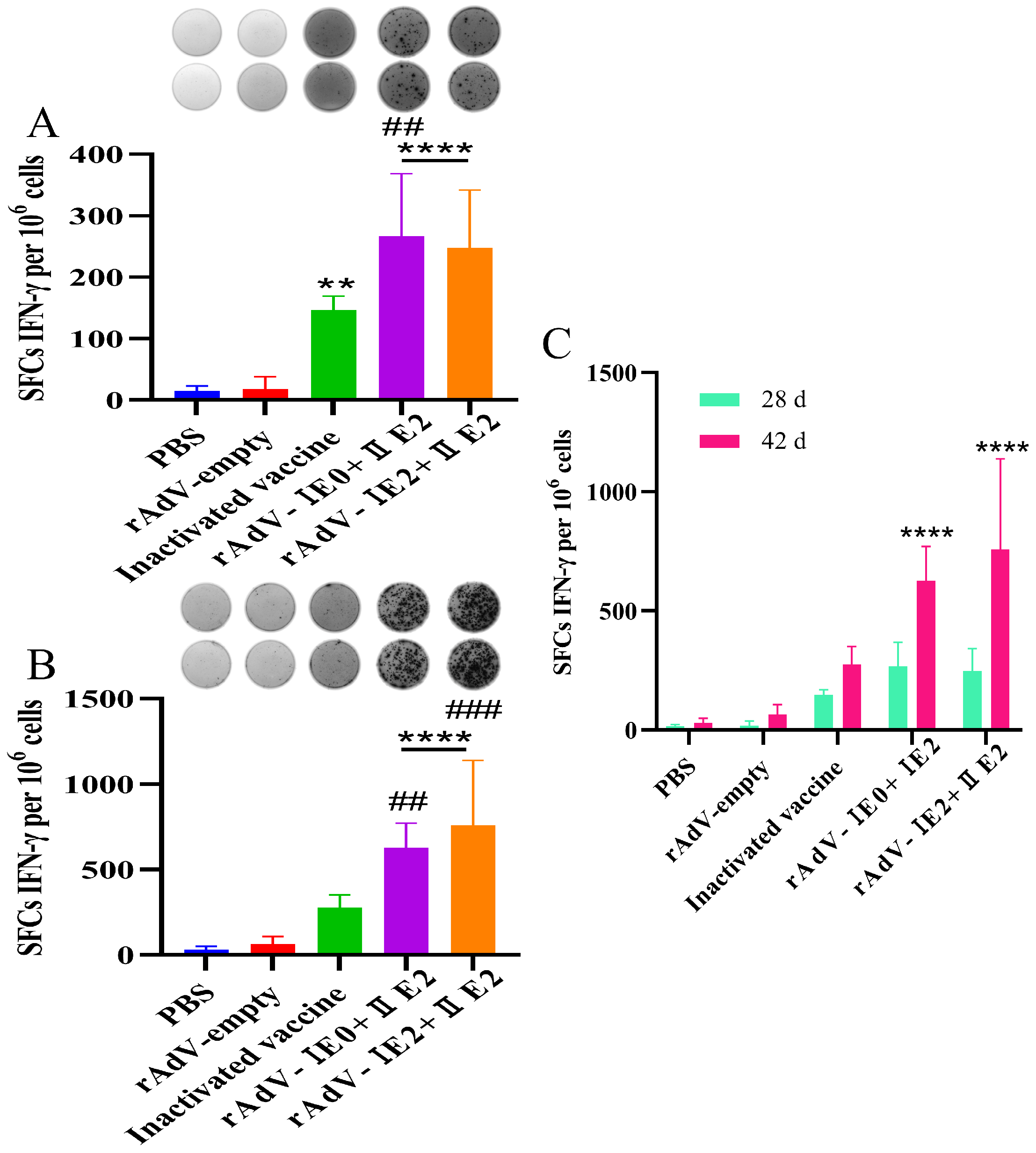

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunospot (ELISpot) Assay

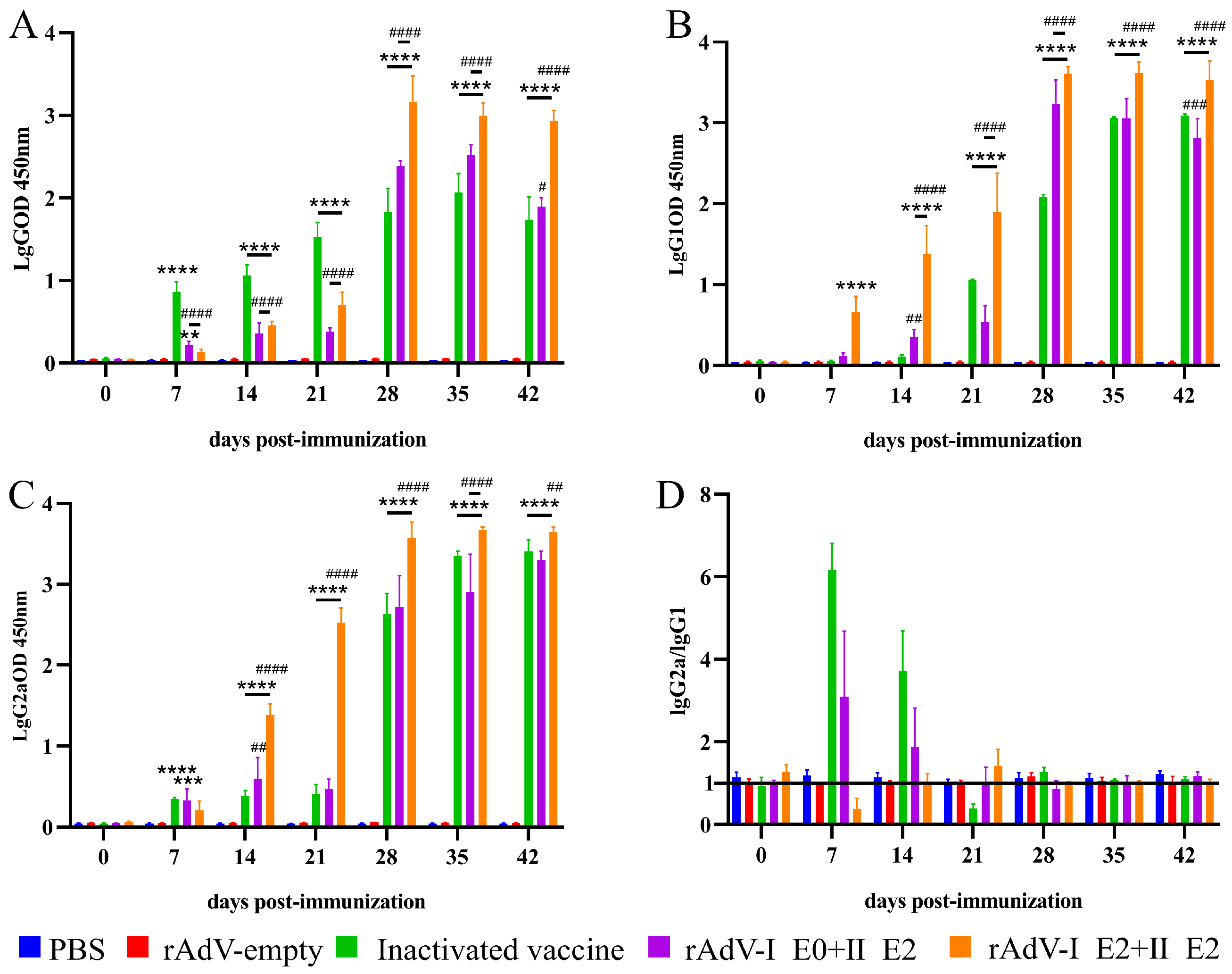

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.7. Virus Neutralization Test (VNT)

2.8. Viral Challenge Experiment

2.9. Sample Collection and Viral Load Quantification

2.10. Histopathological Analysis

2.11. Statistical Analysis

2.12. Illustration Generation

3. Results

3.1. Construction, Characterization, and Identification of rAdV-I E0+I E2 and rAdV-I E2+II E2

3.2. Recombinant Adenovirus Vaccines Elicit Robust and Durable Antigen-Specific IFN-γ Responses

3.3. Adenoviral-Vectored Vaccines Induce Potent Humoral Immunity with Divergent Polarization

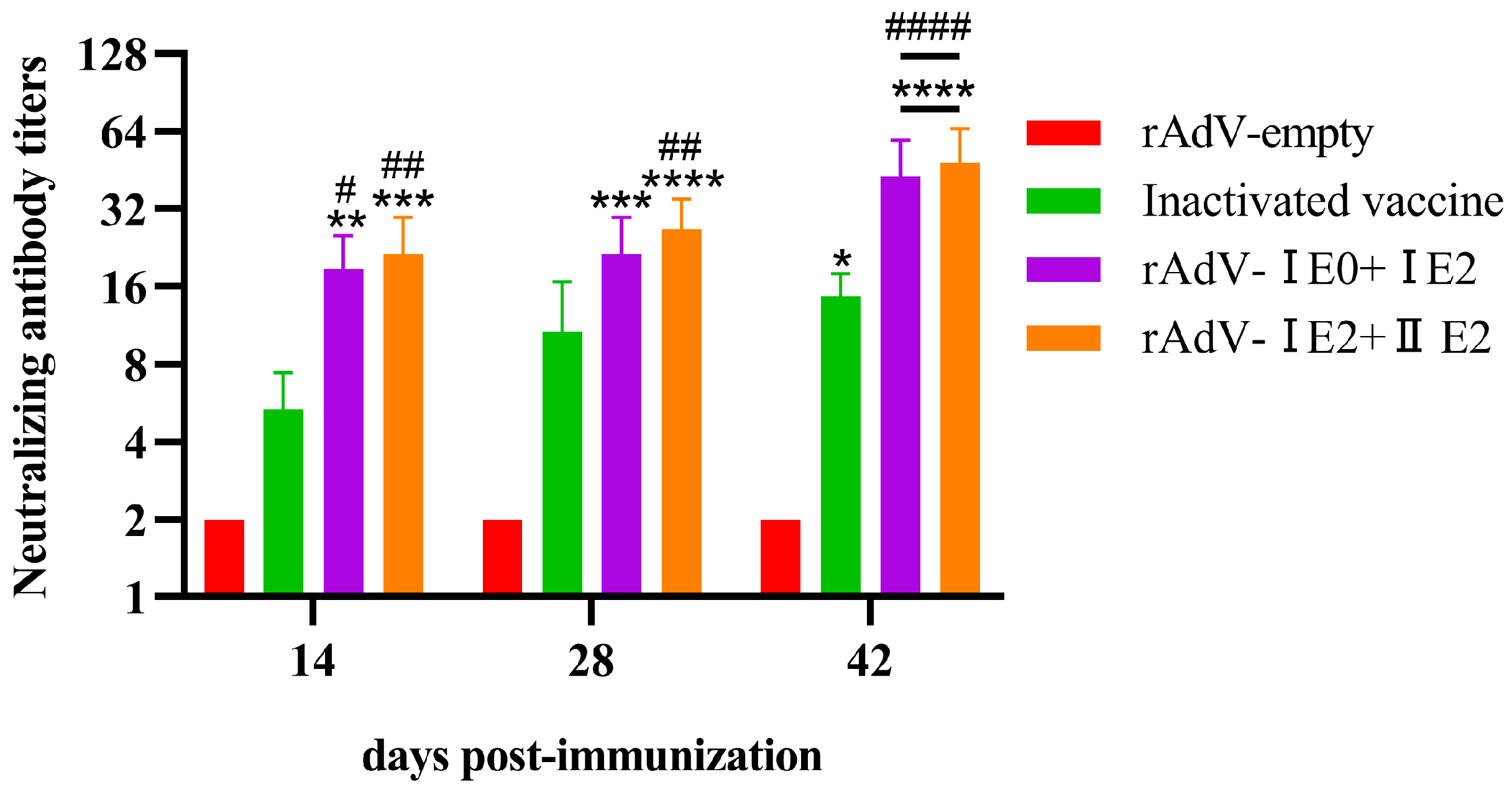

3.4. Induction of Neutralizing Antibodies by Recombinant Adenovirus Vaccines in Mice

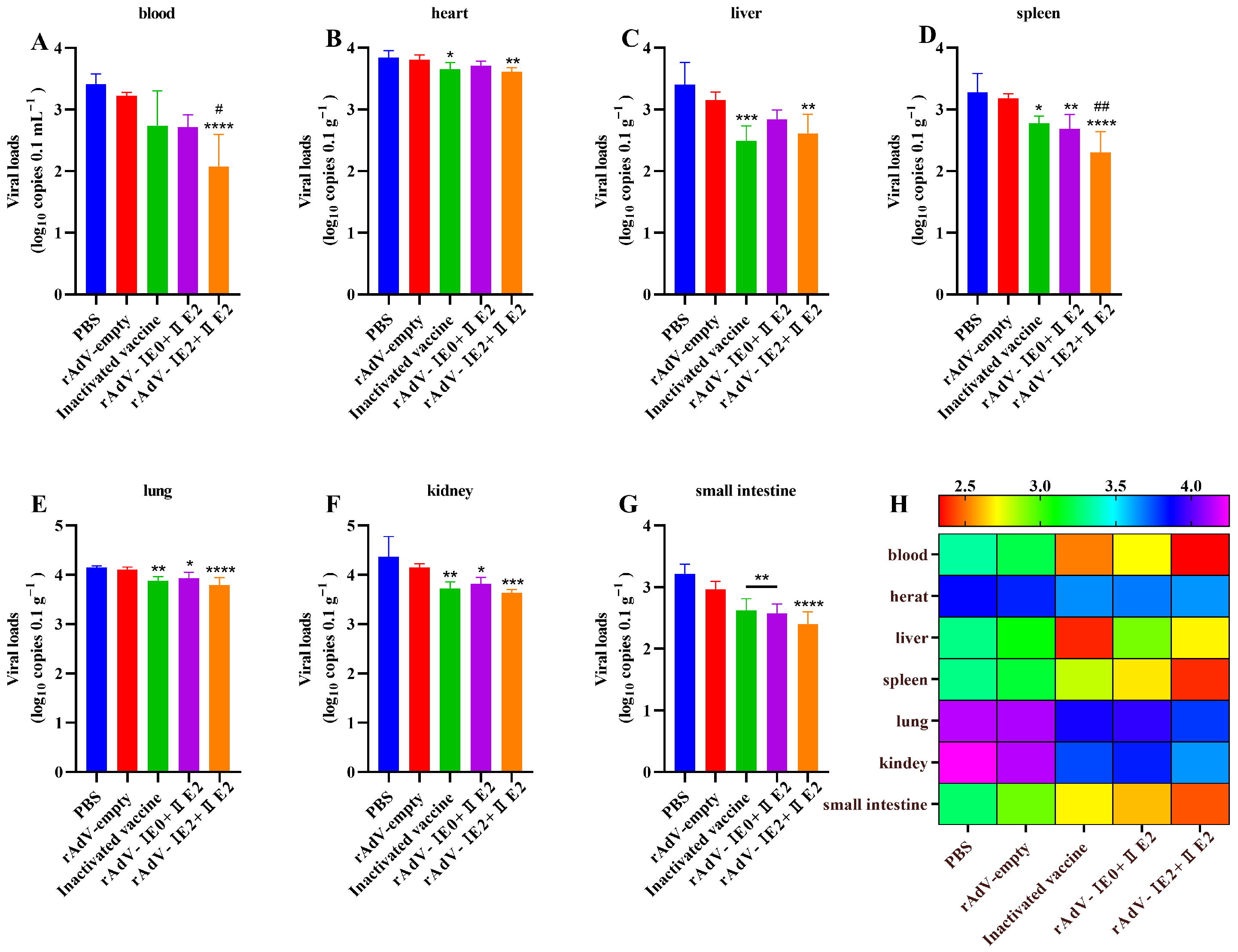

3.5. Protection Against BVDV Infection by Recombinant Adenovirus Vaccines in Mice

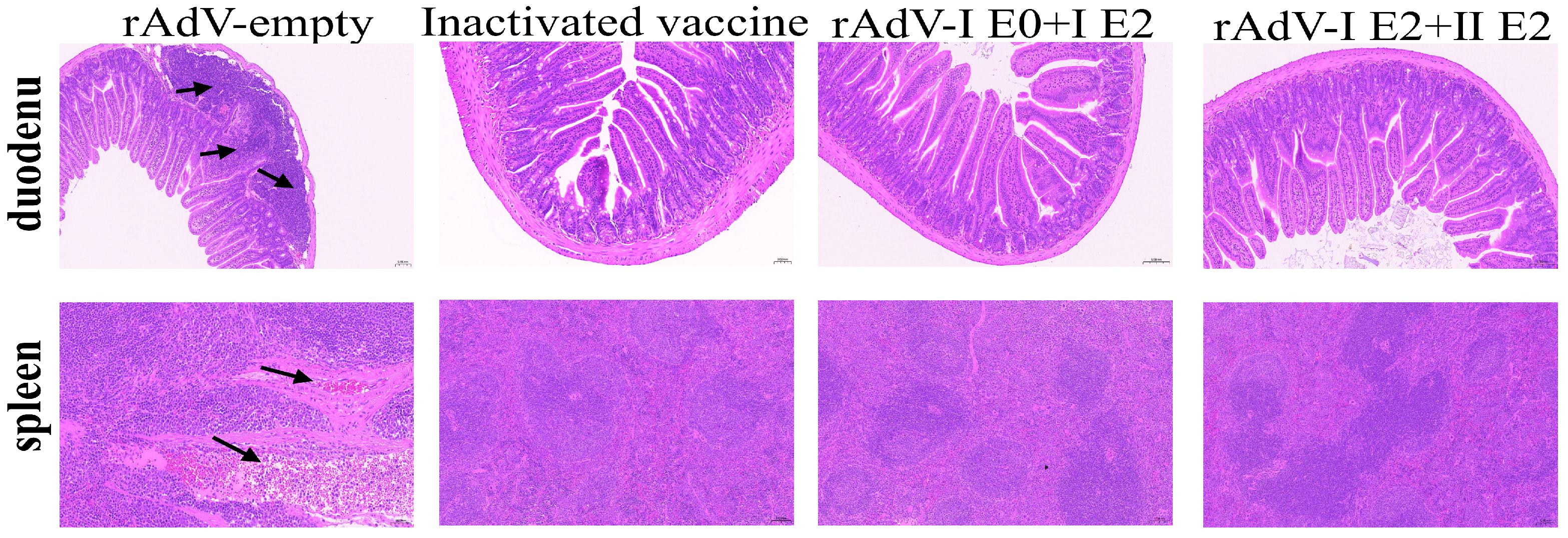

3.6. Vaccination Protects Duodenal and Splenic Architecture from BVDV-Induced Damage

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BVDV | Bovine viral diarrhea virus |

| PI | Persistently infected |

| CPE | Cytopathic effects |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| ELISpot | Enzyme-linked Immunospot |

| ConA | Concanavalin A |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| SFCs | Spot-forming cells |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

| SDs | Standard deviations |

References

- Simmonds, P.; Becher, P.; Bukh, J.; Gould, E.A.; Meyers, G.; Monath, T.; Muerhoff, S.; Pletnev, A.; Rico-Hesse, R.; Smith, D.B.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinior, B.; Garcia, S.; Minviel, J.J.; Raboisson, D. Epidemiological factors and mitigation measures influencing production losses in cattle due to bovine viral diarrhoea virus infection: A meta-analysis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 2426–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauermann, F.V.; Ridpath, J.F. HoBi-like viruses—The typical ‘atypical bovine pestivirus’. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2015, 16, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ren, Y.; Dai, G.; Li, X.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Hou, X.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Genetic characterization and clinical characteristics of bovine viral diarrhea viruses in cattle herds of Heilongjiang province, China. Iran. J. Vet. Res. 2022, 23, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Shi, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Ji, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wu, H. Immunogenicity of an inactivated Chinese bovine viral diarrhea virus 1a (BVDV 1a) vaccine cross protects from BVDV 1b infection in young calves. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2014, 160, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coggins, L.; Gillespie, J.H.; Robson, D.S.; Thompson, J.D.; Phillips, W.V.; Wagner, W.C.; Baker, J.A. Attenuation of virus diarrhea virus (strain Oregon C24V) for vaccine purposes. Cornell Vet. 1961, 51, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abbink, P.; Lemckert, A.A.; Ewald, B.A.; Lynch, D.M.; Denholtz, M.; Smits, S.; Holterman, L.; Damen, I.; Vogels, R.; Thorner, A.R.; et al. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4654–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasaro, M.O.; Ertl, H.C. New insights on adenovirus as vaccine vectors. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 1333–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awakoaiye, B.; Li, S.; Sanchez, S.; Dangi, T.; Irani, N.; Arroyo, L.; Arellano, G.; Mohammadabadi, S.; Aid, M.; Penaloza-MacMaster, P. Comparative analysis of adenovirus, mRNA, and protein vaccines reveals context-dependent immunogenicity and efficacy. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e198069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Shi, H.; Zhou, P.; Zhu, C.; Xing, M.; Zhou, D.; Wang, X. A novel tetravalent influenza vaccine based on one chimpanzee adenoviral vector. Vaccine 2025, 53, 126959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekarek, M.J.; Madapong, A.; Wiggins, J.; Weaver, E.A. Adenoviral-Vectored Multivalent Vaccine Provides Durable Protection Against Influenza B Viruses from Victoria-like and Yamagata-like Lineages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muravyeva, A.; Smirnikhina, S. Adenoviral vectors for gene therapy of hereditary diseases. Biology 2024, 13, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yan, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, S.; Ni, J.; Liu, P. A recombinant adenovirus-vectored PEDV vaccine co-expressing S1 and N proteins enhances mucosal immunity and confers protection in piglets. Vet. Microbiol. 2025, 308, 110633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitt, T.; Kenney, M.; Barrera, J.; Pandya, M.; Eckstrom, K.; Warner, M.; Pacheco, J.M.; LaRocco, M.; Palarea-Albaladejo, J.; Brake, D.; et al. Duration of protection and humoral immunity induced by an adenovirus-vectored subunit vaccine for foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) in Holstein steers. Vaccine 2019, 37, 6221–6231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nobiron, I.; Thompson, I.; Brownlie, J.; Collins, M.E. DNA vaccination against bovine viral diarrhoea virus induces humoral and cellular responses in cattle with evidence for protection against viral challenge. Vaccine 2003, 21, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, D.; Song, Q.; Duan, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y. Enhanced immune responses to E2 protein and DNA formulated with ISA 61 VG administered as a DNA prime-protein boost regimen against bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5591–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, A.A.; Memon, A.M.; Bhuiyan, A.A.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Ye, S.; Li, M.; He, Q.G. The construction of recombinant Lactobacillus casei expressing BVDV E2 protein and its immune response in mice. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 270, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberle, D.; Muhle-Goll, C.; Bürck, J.; Wolf, M.; Reißer, S.; Luy, B.; Wenzel, W.; Ulrich, A.S.; Meyers, G. Structure of the membrane anchor of pestivirus glycoprotein E(rns), a long tilted amphipathic helix. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, S.R. Immunogens of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet. Microbiol. 1993, 37, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, S.; Gao, X.; Guo, X.; Hou, S. Experimental immunization of mice with a recombinant bovine enterovirus vaccine expressing BVDV E0 protein elicits a long-lasting serologic response. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.M.; Shen, S.-H.; Talbot, B.G.; Massie, B.; Harpin, S.; Elazhary, Y. Recombinant adenoviruses expressing the E2 protein of bovine viral diarrhea virus induce humoral and cellular immune responses. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 177, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.M.; Shen, S.H.; Talbot, B.G.; Massie, B.; Harpin, S.; Elazhary, Y. Induction of humoral and cellular immune responses against the nucleocapsid of bovine viral diarrhea virus by an adenovirus vector with an inducible promoter. Virology 1999, 261, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.; Shen, S.-H.; Harpin, S.; Talbot, B.; Elazhary, Y.J. Investigation of the immunological properties of the bovine viral diarrhea virus protein NS3 expressed by an adenovirus vector in mice. Arch. Virol. 1999, 144, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulaszewska, M.; Merelie, S.; Sebastian, S.; Lambe, T. Preclinical immunogenicity of an adenovirus-vectored vaccine for herpes zoster. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2175558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.G.; Wu, A.D.; Liu, J.N.; Yang, Z.L.; Li, H.H.; Ma, H.L.; Yang, N.N.; Sheng, J.L.; Chen, C.F. Inactivated vaccines derived from bovine viral diarrhea virus B3 strain elicit robust and specific humoral and cellular immune responses. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1607334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, R.; Liu, X.; Lv, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Pan, L. Recombinant human adenovirus type 5 based vaccine candidates against GIIa-and GIIb-genotype porcine epidemic diarrhea virus induce robust humoral and cellular response in mice. Virology 2023, 584, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimeno Zoth, S.; Leunda, M.; Odeón, A.; Taboga, O.; Research, B. Recombinant E2 glycoprotein of bovine viral diarrhea virus induces a solid humoral neutralizing immune response but fails to confer total protection in cattle. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2007, 40, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Zhu, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Lou, W.; Zhao, H.; Pan, Z. The recombinant Erns and truncated E2-based indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays to distinguishably test specific antibodies against classical swine fever virus and bovine viral diarrhea virus. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Liang, F.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Prevalence characteristic of BVDV in some large scale dairy farms in Western China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 961337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wang, X.-A.; Chen, X.-M.; Zheng, L.-L.; Chen, H.-Y.; Ma, S.-J. Molecular detection and genotyping of bovine viral diarrhea virus in four provinces of China. Arch. Virol. 2025, 170, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Sun, C.-Q.; Cao, S.-J.; Lin, T.; Yuan, S.-S.; Zhang, H.-B.; Zhai, S.-L.; Huang, L.; Shan, T.-L.; Zheng, H. High prevalence of bovine viral diarrhea virus 1 in Chinese swine herds. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 159, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Yi, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. Virus-like particles vaccines based on glycoprotein E0 and E2 of bovine viral diarrhea virus induce humoral responses. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1047001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhao, H.; Wang, P.; Ma, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Peng, C. Induction of robust and specific humoral and cellular immune responses by bovine viral diarrhea virus virus-like particles (BVDV-VLPs) engineered with baculovirus expression vector system. Vaccines 2021, 9, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Name | Primer Sequences (5′–3′) | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| I E0+I E2-F | ATGGAGAACATCACACAGTGGAACC | 1755 |

| I E0+I E2-R | CGCTAATGACCATGTAGGTGTAGTC | |

| I E2+II E2-F | CTGAGTGTAAGGAGGGCTTT | 2301 |

| I E2+II E2-R | GGGCCTTCTGCTCGCTAATGA |

| Groups (n = 10) | Dose (PFU) | Immunization Time (d) |

|---|---|---|

| rAdV-I E0+I E2 | 107 | 0, 21 |

| rAdV-I E2+II E2 | 107 | 0, 21 |

| rAdV-empty (negative control, NC) | 107 | 0, 21 |

| Inactivated vaccine (positive control, PC) | 100 μL | 0, 21 |

| PBS | 100 μL | 0, 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, M.; Chen, C.; Gao, H.; Guo, H.; Tao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, N.; et al. A Novel Bicistronic Adenovirus Vaccine Elicits Superior and Comprehensive Protection Against BVDV. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020378

Xu M, Chen C, Gao H, Guo H, Tao X, Zhang H, Wang Y, Ma Z, Wang Z, Yang N, et al. A Novel Bicistronic Adenovirus Vaccine Elicits Superior and Comprehensive Protection Against BVDV. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):378. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020378

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Mingguo, Chuangfu Chen, Hengyun Gao, Hao Guo, Xueyu Tao, Huan Zhang, Yong Wang, Zhongchen Ma, Zhen Wang, Ningning Yang, and et al. 2026. "A Novel Bicistronic Adenovirus Vaccine Elicits Superior and Comprehensive Protection Against BVDV" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020378

APA StyleXu, M., Chen, C., Gao, H., Guo, H., Tao, X., Zhang, H., Wang, Y., Ma, Z., Wang, Z., Yang, N., & Zhang, H. (2026). A Novel Bicistronic Adenovirus Vaccine Elicits Superior and Comprehensive Protection Against BVDV. Microorganisms, 14(2), 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020378