Streptococcusdysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis from Diseased Pigs Are Genetically Distinct from Human Strains and Associated with Multidrug Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolate Collection and Clinical Data

2.2. Bacterial Growth Conditions, DNA Preparations and Whole Genome Sequencing

2.3. Species Confirmation, Multilocus Sequencing Tying and emm Typing

2.4. Genome Assembly, Annotation, Mobile Element Detection, Comparative Genomics, and Phylogenetic Analyses

2.5. Screening of Virulence and Regulatory Genes, Lancefield Group Determination, and Antimicrobial Resistance Profiling

2.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.7. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

3. Results

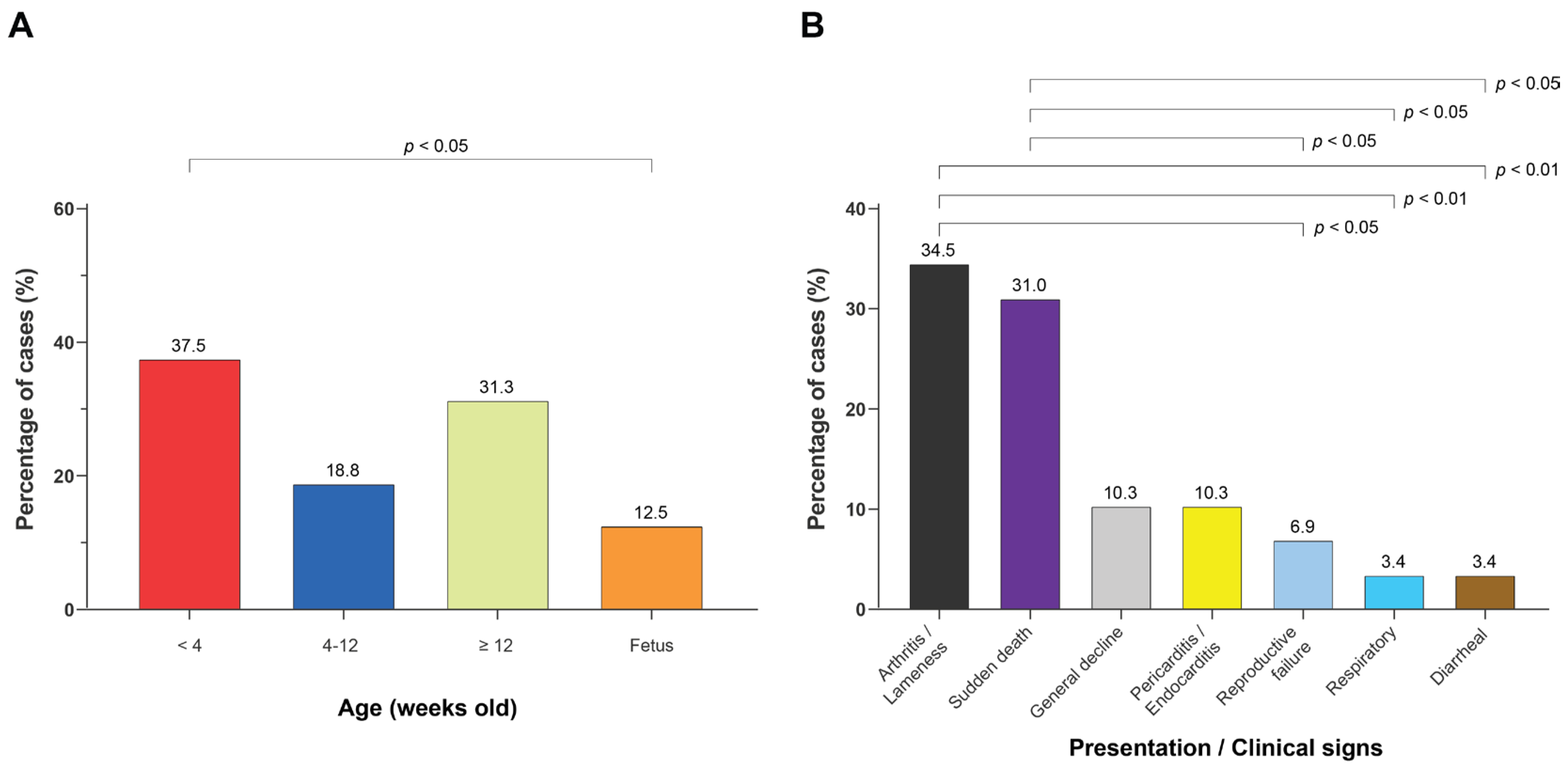

3.1. Porcine SDSE Isolates Were Recovered from Diverse Age Groups and Disease Presentations, with Increasing Frequency over Time

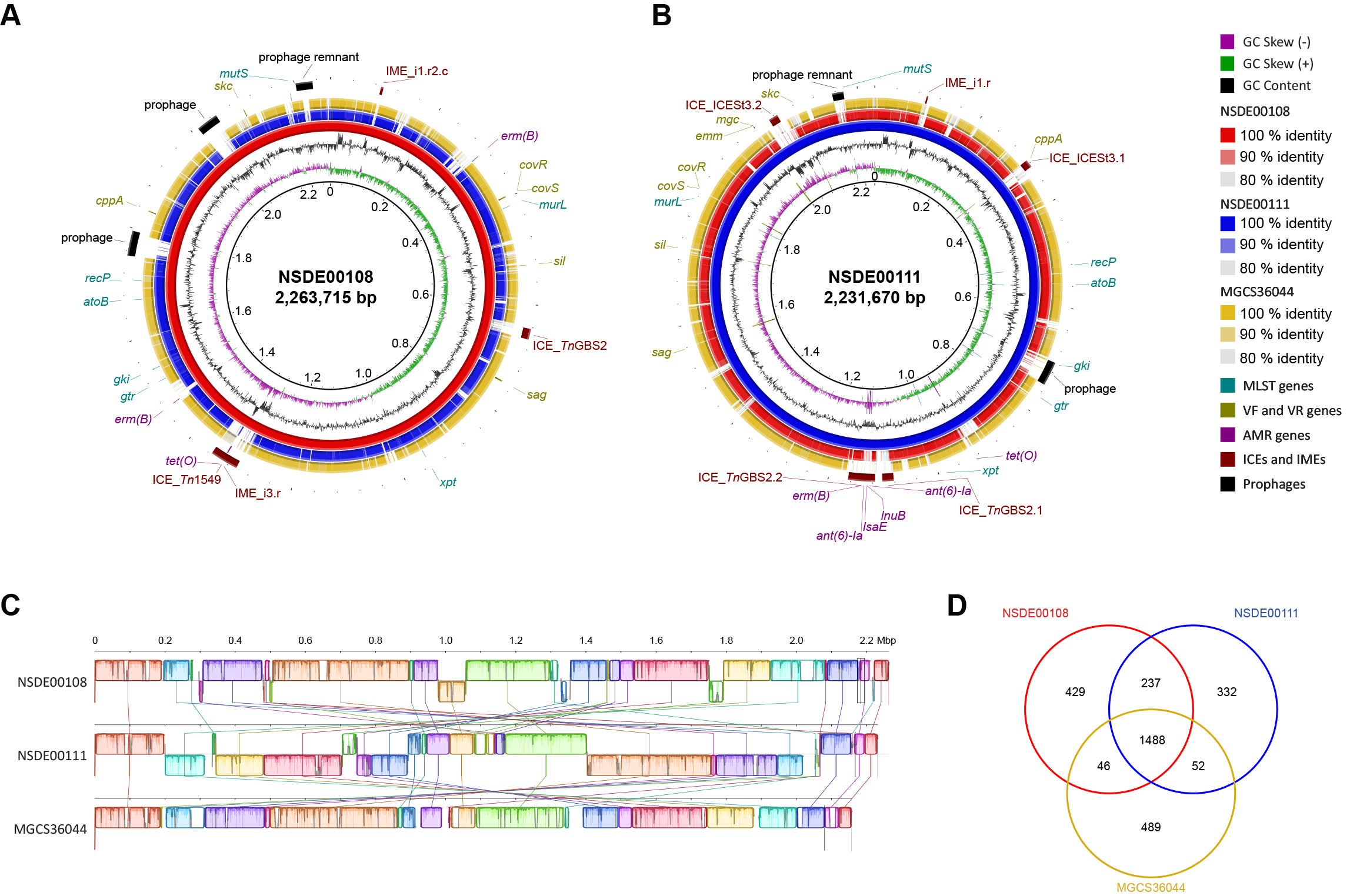

3.2. Comparative Genomics Identifies Structural Variation in Porcine SDSE Isolates and Marked Divergence from a Human Reference Strain

3.3. Core-Genome Phylogeny and MLST Analysis Reveal Extensive Diversity Among Porcine SDSE and Clear Separation from Human Isolates

3.4. Virulence and Regulatory Gene Content Differs Between Hosts but Shows No Consistent Pattern Across Porcine Clades

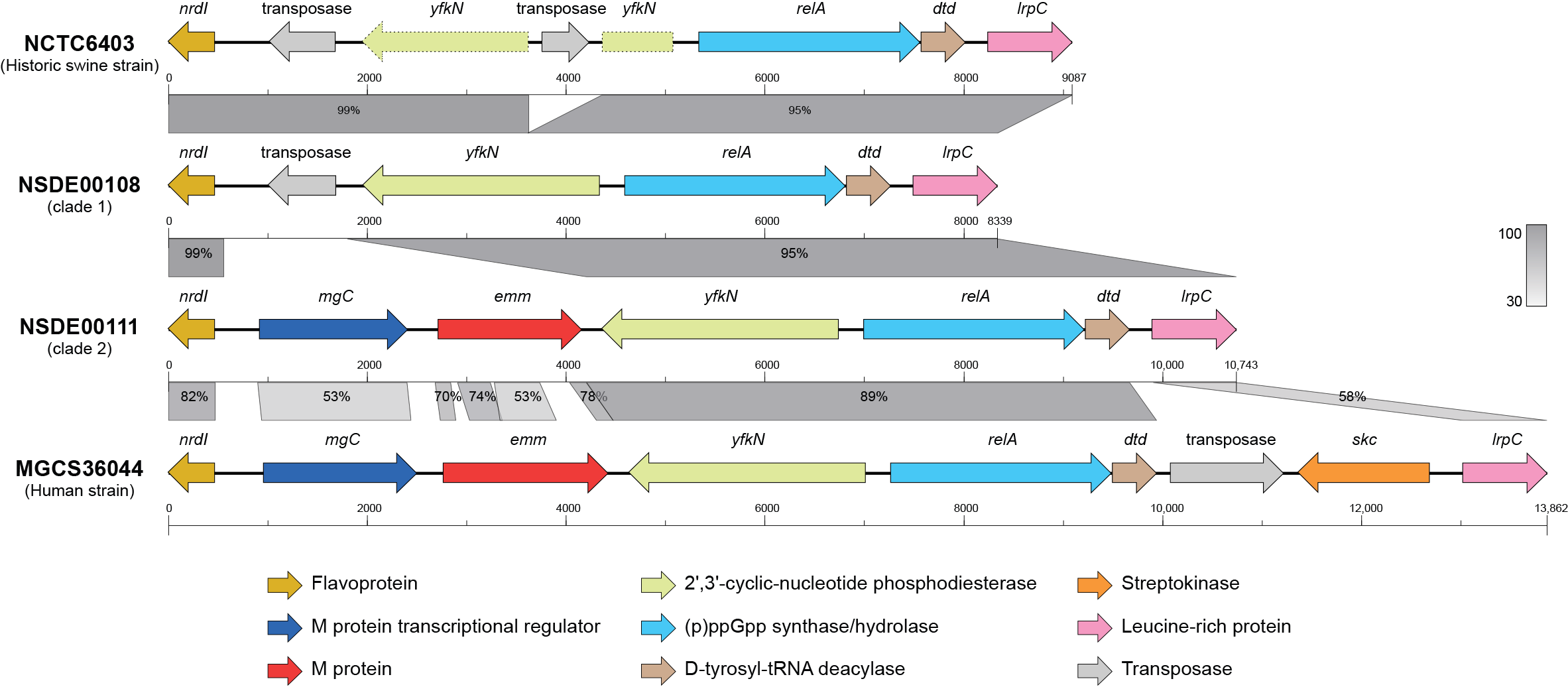

3.5. Loss and Structural Rearrangement of the emm Region Distinguish Porcine SDSE from Human Strains

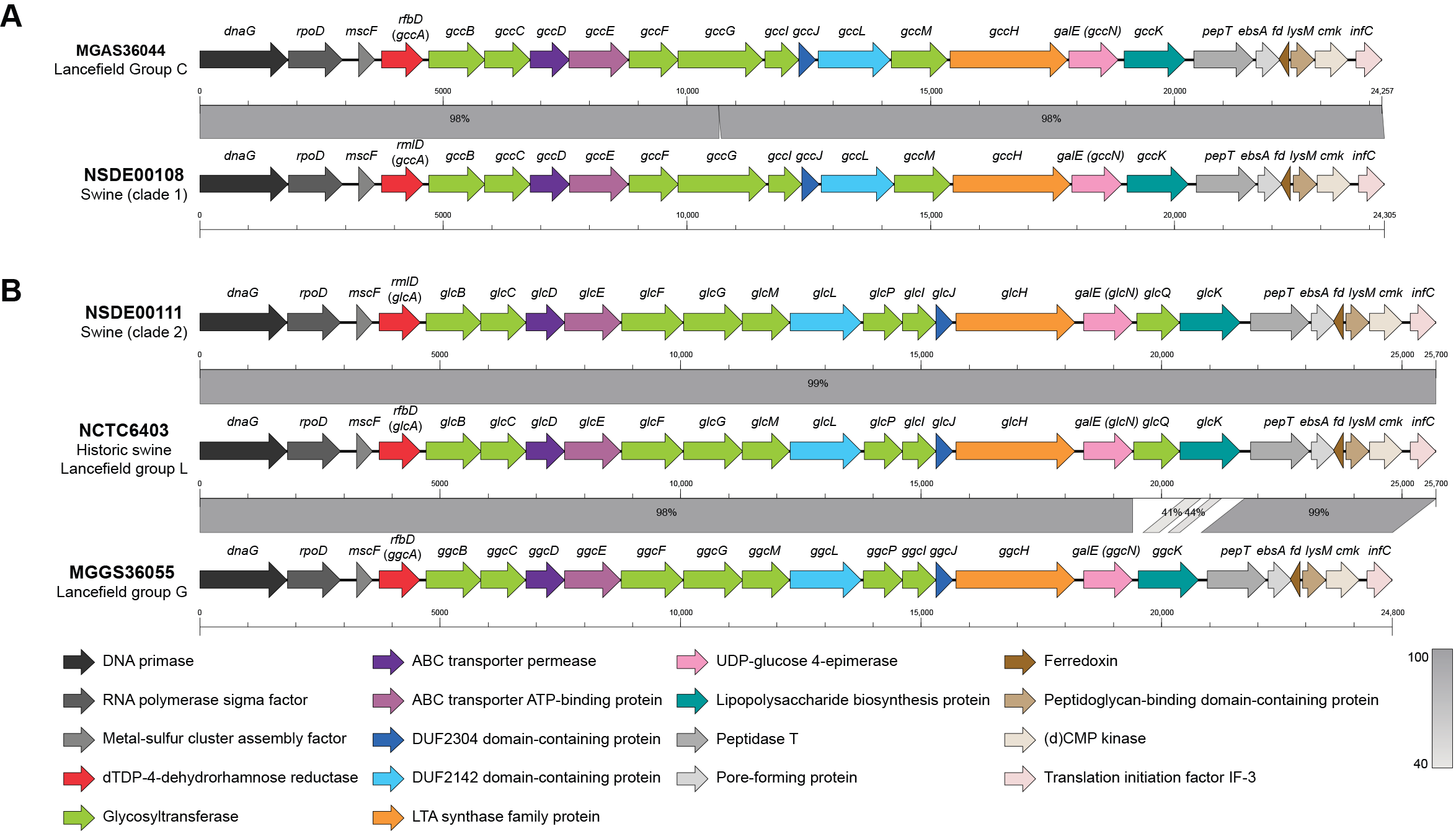

3.6. Variation in Lancefield Antigen Biosynthesis Loci Defines Group C and L Lineages Among Porcine SDSE

3.7. Widespread Antimicrobial Resistance and Multidrug-Resistant Phenotypes Among Porcine SDSE

4. Discussion

4.1. Occurrence and Establishment of SDSE in Swine

4.2. Clinical Features of Porcine SDSE: Contemporary Patterns and Historical Parallels

4.3. Extensive Genomic Diversity Among Porcine SDSE and Divergence from Human-Derived Strains

4.4. Antimicrobial Resistance Reservoir Potential of Swine SDSE

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CARD | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database |

| CC | Clonal complex |

| CDVUM | Centre de diagnostic vétérinaire de l’Université de Montréal |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CovRS | Control of virulence regulon |

| ICE | Integrative and conjugative element |

| IME | Integrative mobilizable element |

| LCB | Local collinear block |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| MAPAQ | Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MGE | Mobile genetic element |

| MLST | Multilocus sequencing typing |

| MST | Minimum-spanning tree |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

| SDSE | Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis |

| Sil | Streptococcal invasive locus |

| SLV | Single-locus variant |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| ST | Sequence type |

| VF | Virulence factor |

| VFDB | Virulence Factors of Pathogenic Bacteria Database |

| VR | Virulence regulator |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

References

- Brandt, C.M.; Spellerberg, B. Human infections due to Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, P.; Pot, B.; Falsen, E.; Kersters, K.; Devriese, L.A. Taxonomic study of lancefield streptococcal groups C, G, and L (Streptococcus dysgalactiae) and proposal of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1996, 46, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facklam, R. What happened to the streptococci: Overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochua, S.; Rivers, J.; Mathis, S.; Li, Z.; Velusamy, S.; McGee, L.; Van Beneden, C.; Li, Y.; Metcalf, B.J.; Beall, B. Emergent Invasive Group A Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, United States, 2015–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1543–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.; Ubukata, K.; Watanabe, H. Invasive infection caused by Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis: Characteristics of strains and clinical features. J. Infect. Chemother. 2011, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunaoshi, K.; Murayama, S.Y.; Adachi, K.; Yagoshi, M.; Okuzumi, K.; Chiba, N.; Morozumi, M.; Ubukata, K. Molecular emm genotyping and antibiotic susceptibility of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolated from invasive and non-invasive infections. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppegaard, O.; Mylvaganam, H.; Skrede, S.; Lindemann, P.C.; Kittang, B.R. Emergence of a Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis stG62647-lineage associated with severe clinical manifestations. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitner, E.; Zollner-Schwetz, I.; Zarfel, G.; Masoud-Landgraf, L.; Gehrer, M.; Wagner-Eibel, U.; Grisold, A.J.; Feierl, G. Prevalence of emm types and antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in Austria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 305, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruun, T.; Kittang, B.R.; de Hoog, B.J.; Aardal, S.; Flaatten, H.K.; Langeland, N.; Mylvaganam, H.; Vindenes, H.A.; Skrede, S. Necrotizing soft tissue infections caused by Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis of groups C and G in western Norway. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, E545–E550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, O.; Davies, M.R.; Tong, S.Y.C. Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis infection and its intersection with Streptococcus pyogenes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e0017523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Takemoto, N.; Ogura, K.; Miyoshi-Akiyama, T. Severe invasive streptococcal infection by Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, C.P.; Retamar, G.; Leiva, R.; Frosth, S.; Ivanissevich, A.; Demarchi, M.E.; Walsh, S.; Frykberg, L.; Guss, B.; Mesplet, M.; et al. Novel Genotype of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis Associated with Mastitis in an Arabian Filly: Genomic Approaches and Phenotypic Properties. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 130, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, M.D.; Erol, E.; Ribeiro-Goncalves, B.; Mendes, C.I.; Carrico, J.A.; Matos, S.C.; Preziuso, S.; Luebke-Becker, A.; Wieler, L.H.; Melo-Cristino, J.; et al. Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus dysgalactiae strains isolated from horses are a genetically distinct population within the Streptococcus dysgalactiae taxon. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.G.; Genteluci, G.L.; Correa de Mattos, M.; Glatthardt, T.; Sa Figueiredo, A.M.; Ferreira-Carvalho, B.T. Group C Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in south-east Brazil: Genetic diversity, resistance profile and the first report of human and equine isolates belonging to the same multilocus sequence typing lineage. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottschalk, M.; Segura, M.; de Oliveira Costa, M. Streptococcus spp. In Diseases of Swine; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1097–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.I.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.; So, B.; Kim, B.; Kim, H.Y. Molecular subtyping and antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis isolates from clinically diseased pigs. J. Vet. Sci. 2020, 21, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.I.; Kim, J.W.; Jung, J.Y.; Chae, M.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, J.H.; So, B.; Kim, H.Y. Pathologic and molecular characterization of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis infection in neonatal piglets. J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 19, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.Z.; da Costa, B.L.; Matajira, C.E.; Gomes, V.T.; Mesquita, R.E.; Silva, A.P.; Moreno, A.M. Molecular and antimicrobial susceptibility profiling of Streptococcus dysgalactiae isolated from swine. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 86, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, K.; Yoshida, E.; Harada, R.; Hasegawa, M.; Osaka, H.; Kato, M.; Shibahara, T. Systemic Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis infection in a Yorkshire pig with severe disseminated suppurative meningoencephalomyelitis. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2014, 76, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, H.; Tanaka, T.; Nishiya, H.; Gunji, Y.; Uto, S.; Inoue, M.; Chuma, T. Antimicrobial Susceptibilities and Resistant Genes in β-hemolytic Streptococci Isolated from Endocarditis in Slaughtered Pigs. J. Jpn. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 66, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, K.; Minakami, T.; Mori, Y.; Katsumi, M.; Kataoka, Y.; Ezawa, A.; Kikuchi, N.; Takahashi, T. rDNA sequence analyses of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates from pigs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1941–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.M.; Sahoo, M.; Thakor, J.C.; Murali, D.; Kumar, P.; Singh, R.; Singh, K.P.; Saikumar, G.; Jana, C.; Patel, S.K.; et al. Pathomolecular epidemiology, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence genes of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates from slaughtered pigs in India. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 135, lxae002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrieber, L.; Towers, R.; Muscatello, G.; Speare, R. Transmission of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis between child and dog in an Aboriginal Australian community. Zoonoses Public Health 2014, 61, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcellato, D.; Smistad, M.; Skeie, S.B.; Jorgensen, H.J.; Austbo, L.; Oppegaard, O. Whole genome sequencing reveals possible host species adaptation of Streptococcus dysgalactiae. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Chan, J.; Connor, R.; Feldgarden, M.; Fine, A.M.; Funk, K.; Hoffman, J.; et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D20–D29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lacouture, S.; Lewandowski, E.; Thibault, E.; Gantelet, H.; Gottschalk, M.; Fittipaldi, N. Molecular characterization of Streptococcus suis isolates recovered from diseased pigs in Europe. Vet. Res. 2024, 55, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, M.; Dashnow, H.; Raven, L.-A.; Schultz, M.B.; Pope, B.J.; Tomita, T.; Zobel, J.; Holt, K.E. SRST2: Rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med. 2014, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Maiden, M.C.J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018, 3, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.J.; Bessen, D.E.; Pinho, M.; Ford, C.; Hall, G.S.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Ramirez, M. Population genetics of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis reveals widely dispersed clones and extensive recombination. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.; Sousa, A.; Ramirez, M.; Francisco, A.P.; Carrico, J.A.; Vaz, C. PHYLOViZ 2.0: Providing scalable data integration and visualization for multiple phylogenetic inference methods. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, T.B.; Teatero, S.; Li, A.; Marchand-Austin, A.; Beall, B.W.; Fittipaldi, N. Deriving group A Streptococcus typing information from short-read whole-genome sequencing data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1871–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, M.H.K.; Bortolaia, V.; Tansirichaiya, S.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Roberts, A.P.; Petersen, T.N. Detection of mobile genetic elements associated with antibiotic resistance in Salmonella enterica using a newly developed web tool: MobileElementFinder. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lao, J.; Lacroix, T.; Guedon, G.; Coluzzi, C.; Payot, S.; Leblond-Bourget, N.; Chiapello, H. ICEscreen: A tool to detect Firmicute ICEs and IMEs, isolated or enclosed in composite structures. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2022, 4, lqac079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Han, S.; Saha, S.; Oler, E.; Peters, H.; Grant, J.R.; Stothard, P.; Gautam, V. PHASTEST: Faster than PHASTER, better than PHAST. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W443–W450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritt, A.; Eisen, J.A.; Facciotti, M.T.; Darling, A.E. An integrated pipeline for de novo assembly of microbial genomes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Snippy: Rapid Haploid Variant Calling and Core Genome Alignment. GitHub. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/snippy (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Beres, S.B.; Olsen, R.J.; Long, S.W.; Eraso, J.M.; Boukthir, S.; Faili, A.; Kayal, S.; Musser, J.M. Analysis of the Genomics and Mouse Virulence of an Emergent Clone of Streptococcus dysgalactiae Subspecies equisimilis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0455022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Li, L.; Luo, X.; Chen, M.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; Dai, Z.; Lam, T.T.; Guan, Y.; Yu, G. Ggtree: A serialized data object for visualization of a phylogenetic tree and annotation data. Imeta 2022, 1, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, A.E.; Mau, B.; Perna, N.T. progressiveMauve: Multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branger, M.; Leclercq, S.O. GenoFig: A user-friendly application for the visualization and comparison of genomic regions. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.H.; Yu, G.; Cai, P. ggVennDiagram: An Intuitive, Easy-to-Use, and Highly Customizable R Package to Generate Venn Diagram. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 706907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z. Complex heatmap visualization. Imeta 2022, 1, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2022: A general classification scheme for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D912–D917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reglinski, M.; Sriskandan, S.; Turner, C.E. Identification of two new core chromosome-encoded superantigens in Streptococcus pyogenes; speQ and speR. J. Infect. 2019, 78, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commons, R.J.; Smeesters, P.R.; Proft, T.; Fraser, J.D.; Robins-Browne, R.; Curtis, N. Streptococcal superantigens: Categorization and clinical associations. Trends Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, L.A.; Malke, H.; McIver, K.S. Virulence-Related Transcriptional Regulators of Streptococcus pyogenes. In Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations; University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center: Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zorzoli, A.; Meyer, B.H.; Adair, E.; Torgov, V.I.; Veselovsky, V.V.; Danilov, L.L.; Uhrin, D.; Dorfmueller, H.C. Group A, B, C, and G Streptococcus Lancefield antigen biosynthesis is initiated by a conserved alpha-d-GlcNAc-beta-1,4-l-rhamnosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 15237–15256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florensa, A.F.; Kaas, R.S.; Clausen, P.; Aytan-Aktug, D.; Aarestrup, F.M. ResFinder—An open online resource for identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next-generation sequencing data and prediction of phenotypes from genotypes. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; Syed, S.A.; Tsang, K.K.; et al. CARD 2023: Expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.W.; Perry, D.M.; Kirby, W.M. Single-disk antibiotic-sensitivity testing of staphylococci; an analysis of technique and results. AMA Arch. Intern. Med. 1959, 104, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals, 6th ed.; CLSI Guideline VET01; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rafailidis, P.I.; Kofteridis, D. Proposed amendments regarding the definitions of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant bacteria. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinkova, J.; Bícovă, R.; Rotta, J. Some manifestations of a relationship between group A and L streptococci. Preliminary report. J. Hyg. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 1967, 11, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufuss, P.; Lämmler, C.; Niewerth, B.; Blobel, H. Properties of L-streptococci in comparison with those of A-streptococci. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1987, 176, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 35th ed.; CLSI Guideline M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kaci, A.; Jonassen, C.M.; Skrede, S.; Sivertsen, A.; Norwegian Study Group on Streptococcus dysgalactiae; Steinbakk, M.; Oppegaard, O. Genomic epidemiology of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strains causing invasive disease in Norway during 2018. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1171913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, T.; Fry, R.; Orr, A. First Impressions of the Bets Haemolytic Streptocoecus Infection of Swine. Vet. Rec. 1942, 54, 267–269. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.E. The serological classification of streptococci isolated from diseased pigs. Br. Vet. J. 1976, 132, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommez, J.; Devriese, L.A.; Castryck, F.; Miry, C. Beta-hemolytic streptococci from pigs: Bacteriological diagnosis. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. B 1991, 38, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, M.; Berglund, M.; Pettersson, M.; Sandstrom, M.; Matti, F.; Sjolund, M.; Backhans, A.; Ytrehus, B.; Ekman, S. Pathological and bacteriological findings in sows, finisher pigs, and piglets, being culled for lameness. Porcine Health Manag. 2025, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinthi, M.; Massacci, F.R.; Coccitto, S.N.; Albini, E.; Cucco, L.; Orsini, M.; Simoni, S.; Giovanetti, E.; Brenciani, A.; Magistrali, C.F. Characterization of a prophage and a defective integrative conjugative element carrying the optrA gene in linezolid-resistant Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolates from pigs, Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1740–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoric, M.; Nilsson, E.; Lundeheim, N.; Wallgren, P. Incidence of lameness and abrasions in piglets in identical farrowing pens with four different types of floor. Acta Vet. Scand. 2009, 51, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumi, M.; Kataoka, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Kikuchi, N.; Hiramune, T. Biochemical and serological examination of beta-hemolytic streptococci isolated from slaughtered pigs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1998, 60, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Laddika, L.; Dinesh, M.; Maganbhai, B.J.; Malik, S.; Sahoo, M.; Qureshi, S.; Tiwari, A.K. Isolation, Molecular Identification and Antibiogram of Streptococcus dysgalactiae Isolates Recovered from Pigs. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 3026–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glambek, M.; Skrede, S.; Sivertsen, A.; Kittang, B.R.; Kaci, A.; Jonassen, C.M.; Jorgensen, H.J.; Norwegian Study Group on Streptococcus dysgalactiae; Oppegaard, O. Antimicrobial resistance patterns in Streptococcus dysgalactiae in a One Health perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1423762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Fang, Y.; Huang, L.; Diao, B.; Du, X.; Kan, B.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, F.; Li, D.; Wang, D. Molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance of clinical Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in Beijing, China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 40, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, K.; Murase, K.; Tsuchido, Y.; Noguchi, T.; Yukawa, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Nakagawa, I.; Nagao, M. Clonal Expansion of Multidrug-Resistant Streptococcus dysgalactiae Subspecies equisimilis Causing Bacteremia, Japan, 2005–2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scicchitano, D.; Leuzzi, D.; Babbi, G.; Palladino, G.; Turroni, S.; Laczny, C.C.; Wilmes, P.; Correa, F.; Leekitcharoenphon, P.; Savojardo, C.; et al. Dispersion of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in pig farms and in the surrounding environment. Anim. Microbiome 2024, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monger, X.C.; Gilbert, A.A.; Saucier, L.; Vincent, A.T. Antibiotic Resistance: From Pig to Meat. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antimicrobial | Category d | Zone Diameter Breakpoints (mm) | Number of Isolates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | Susceptible (n, %) | Intermediate (n, %) | Resistant (n, %) | ||

| Penicillin a | II | ≥24 | – | – | 41 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ceftiofur b | I | ≥21 | 20–18 | ≤17 | 41 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Florfenicol b | III | ≥22 | 21–19 | ≤18 | 41 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Enrofloxacin b | I | ≥23 | 22–17 | ≤16 | 36 (87.8) | 5 (12.2) | 0 (0) |

| Gentamicin c | II | ≥15 | 14–13 | ≤12 | 37 (90.2) | 2 (4.9) | 2 (4.9) |

| Trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole a | II | ≥19 | 18–16 | ≤15 | 31 (75.6) | 8 (19.5) | 2 (4.9) |

| Erythromycin a | II | ≥21 | 20–16 | ≤15 | 25 (61.0) | 0 (0) | 16 (39.0) |

| Clindamycin a | II | ≥19 | 18–16 | ≤15 | 13 (31.7) | 0 (0) | 28 e (68.3) |

| Tetracycline a | III | ≥23 | 22–19 | ≤18 | 0 (0) | 7 (17.1) | 34 (82.9) |

| Number of Drug Class Combinations | Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern | Number of Isolates (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | 4 (9.8) |

| 1 | Tetracycline | 4 (9.8) |

| Aminoglycoside | 2 (4.9) | |

| 2 | Aminoglycoside-Tetracycline | 2 (4.9) |

| 3 a | Macrolide-Streptogramin-Lincosamide | 1 (2.4) |

| 4 a | Macrolide-Streptogramin-Lincosamide-Tetracycline | 2 (4.9) |

| 5 a | Aminoglycoside-Streptogramin-Lincosamide-Pleuromutilin-Tetracycline | 9 (22.0) |

| 5 a | Aminoglycoside-Macrolide-Streptogramin-Lincosamide-Tetracycline | 1 (2.4) |

| 5 a | Aminoglycoside-Macrolide-Streptogramin-Lincosamide-Pleuromutilin | 1 (2.4) |

| 6 b | Aminoglycoside-Macrolide-Streptogramin-Lincosamide-Pleuromutilin-Tetracycline | 12 (29.3) |

| 6 b | Macrolide-Streptogramin-Lincosamide-Pleuromutilin-Tetracycline-Ionophores | 1 (2.4) |

| 7 b | Aminoglycoside-Macrolide-Streptogramin-Lincosamide-Pleuromutilin-Nucleoside-Tetracycline | 1 (2.4) |

| 7 b | Aminoglycoside-Macrolide-Streptogramin-Lincosamide-Pleuromutilin-Tetracycline-Ionophores | 1 (2.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hsu, F.; Gauvin, K.; Li, K.; Fairbrother, J.-H.; Simpson, J.; Gottschalk, M.; Fittipaldi, N. Streptococcusdysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis from Diseased Pigs Are Genetically Distinct from Human Strains and Associated with Multidrug Resistance. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010009

Hsu F, Gauvin K, Li K, Fairbrother J-H, Simpson J, Gottschalk M, Fittipaldi N. Streptococcusdysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis from Diseased Pigs Are Genetically Distinct from Human Strains and Associated with Multidrug Resistance. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Fengyang, Kayleigh Gauvin, Kevin Li, Julie-Hélène Fairbrother, Jared Simpson, Marcelo Gottschalk, and Nahuel Fittipaldi. 2026. "Streptococcusdysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis from Diseased Pigs Are Genetically Distinct from Human Strains and Associated with Multidrug Resistance" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010009

APA StyleHsu, F., Gauvin, K., Li, K., Fairbrother, J.-H., Simpson, J., Gottschalk, M., & Fittipaldi, N. (2026). Streptococcusdysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis from Diseased Pigs Are Genetically Distinct from Human Strains and Associated with Multidrug Resistance. Microorganisms, 14(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010009