Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Growth Performance, Enzyme Activity, Rumen Microbial Diversity and Metabolomic Profiles in Yak Calves

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Experimental Diet

2.3. Determination of Growth Performance

2.4. Sample Collection

2.5. Determination of Rumen Fluid VFAs

2.6. Enzyme Activity Determination

2.7. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.8. Metabolite Determination

2.9. Data Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Feeding Methods on the Growth Performance of Yak Calves

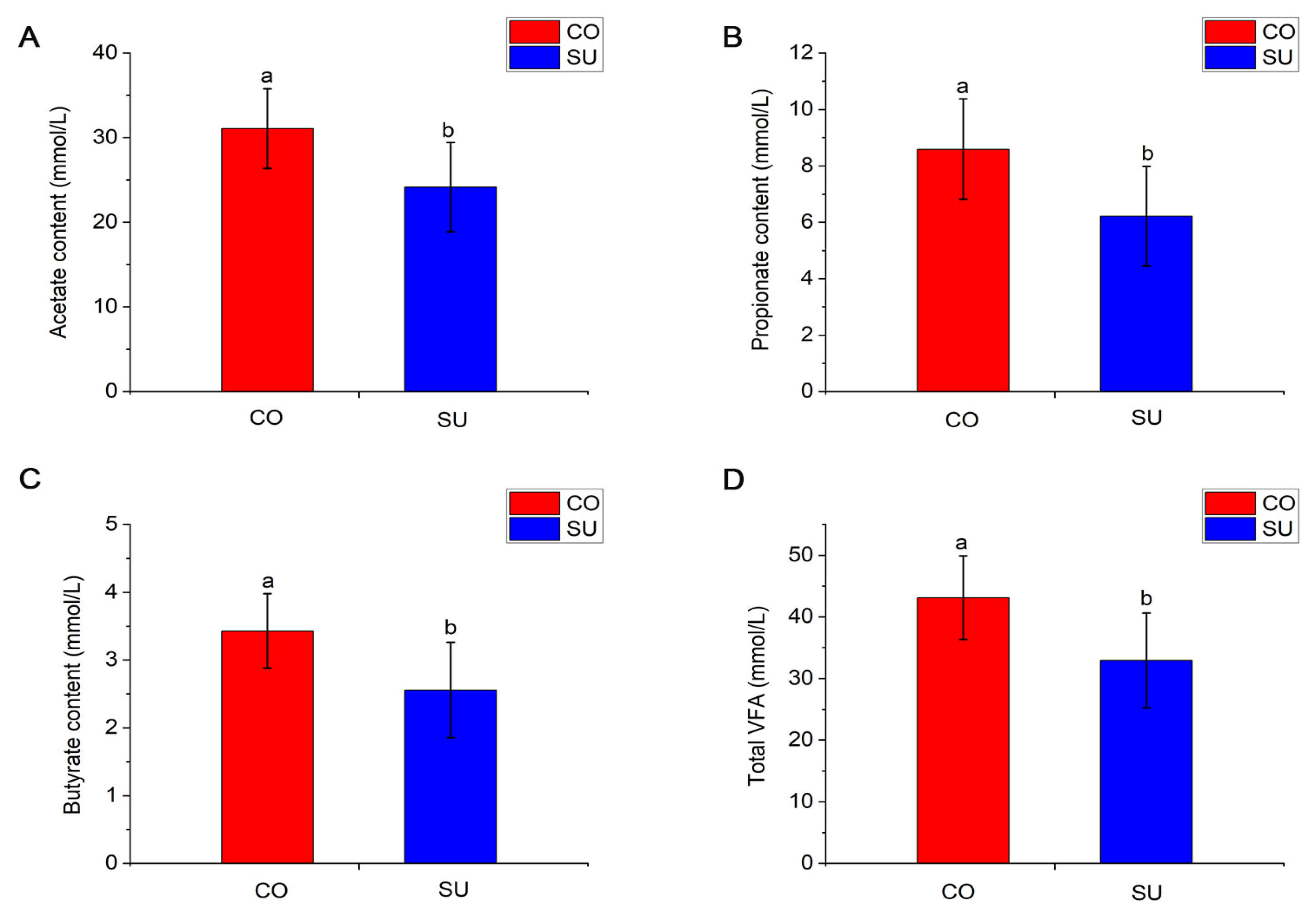

3.2. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Rumen VFA Content of Yak Calves

3.3. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Enzyme Activities of Yak Calves

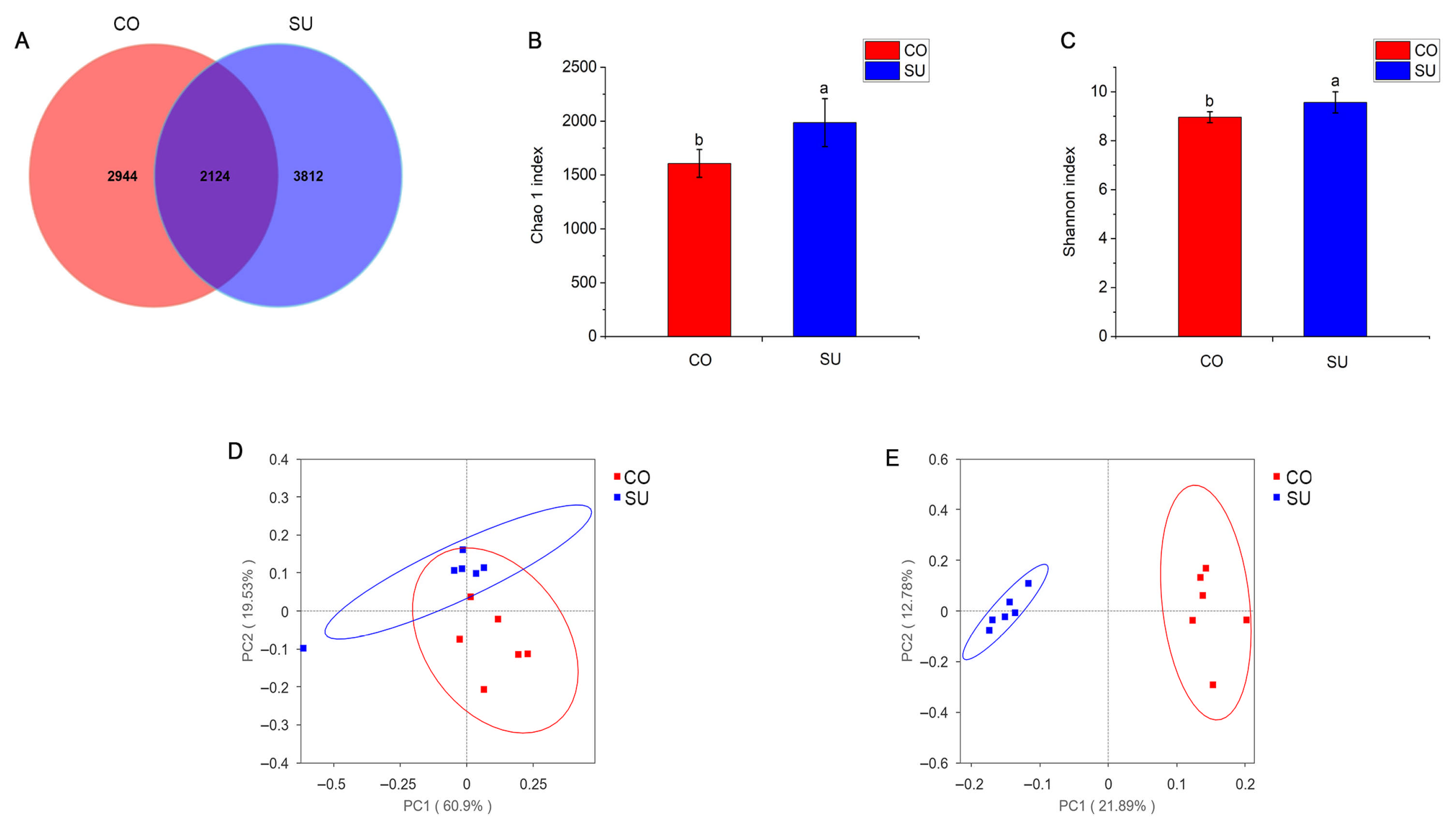

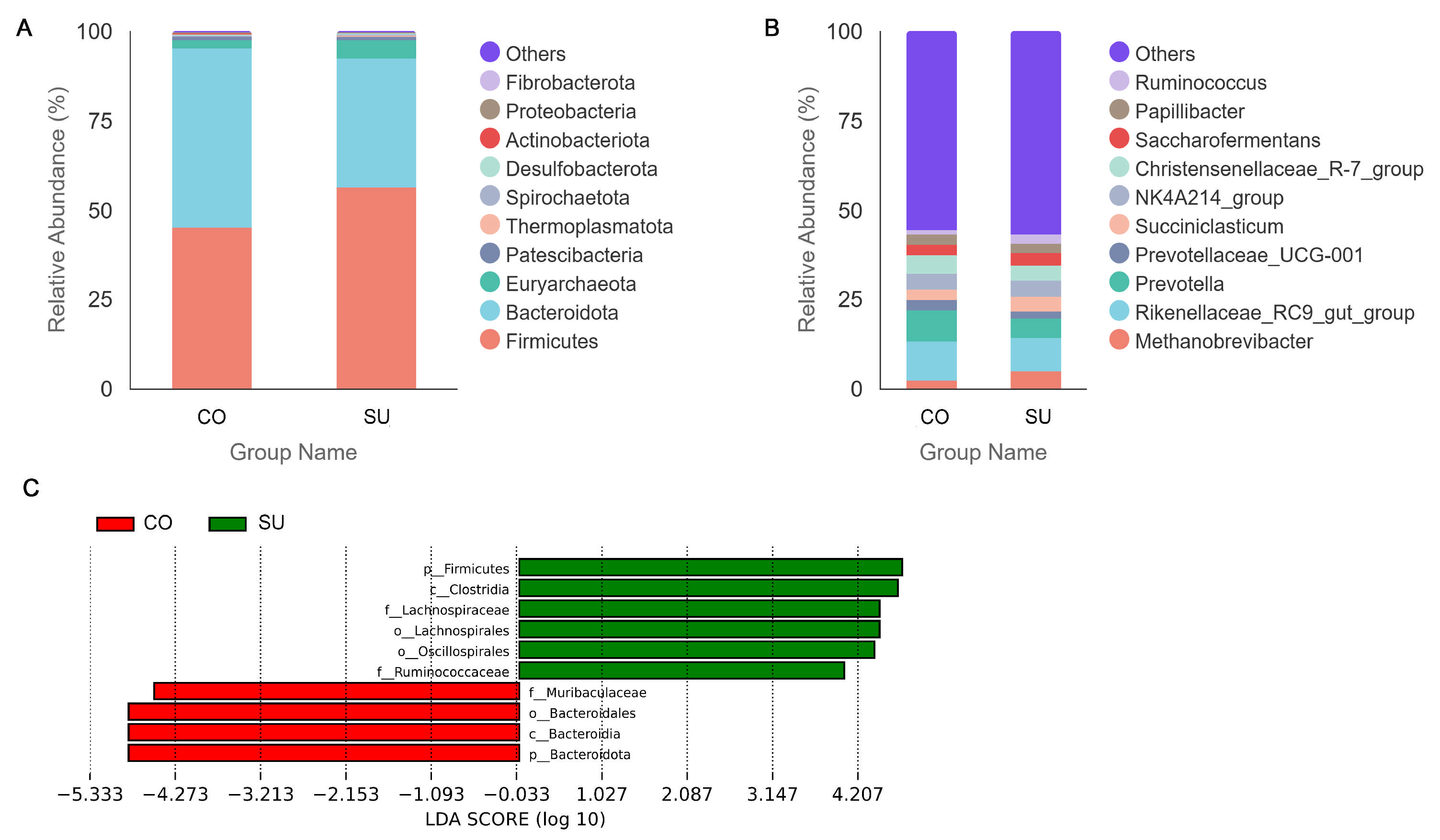

3.4. Analysis of Rumen Microbial Community Composition

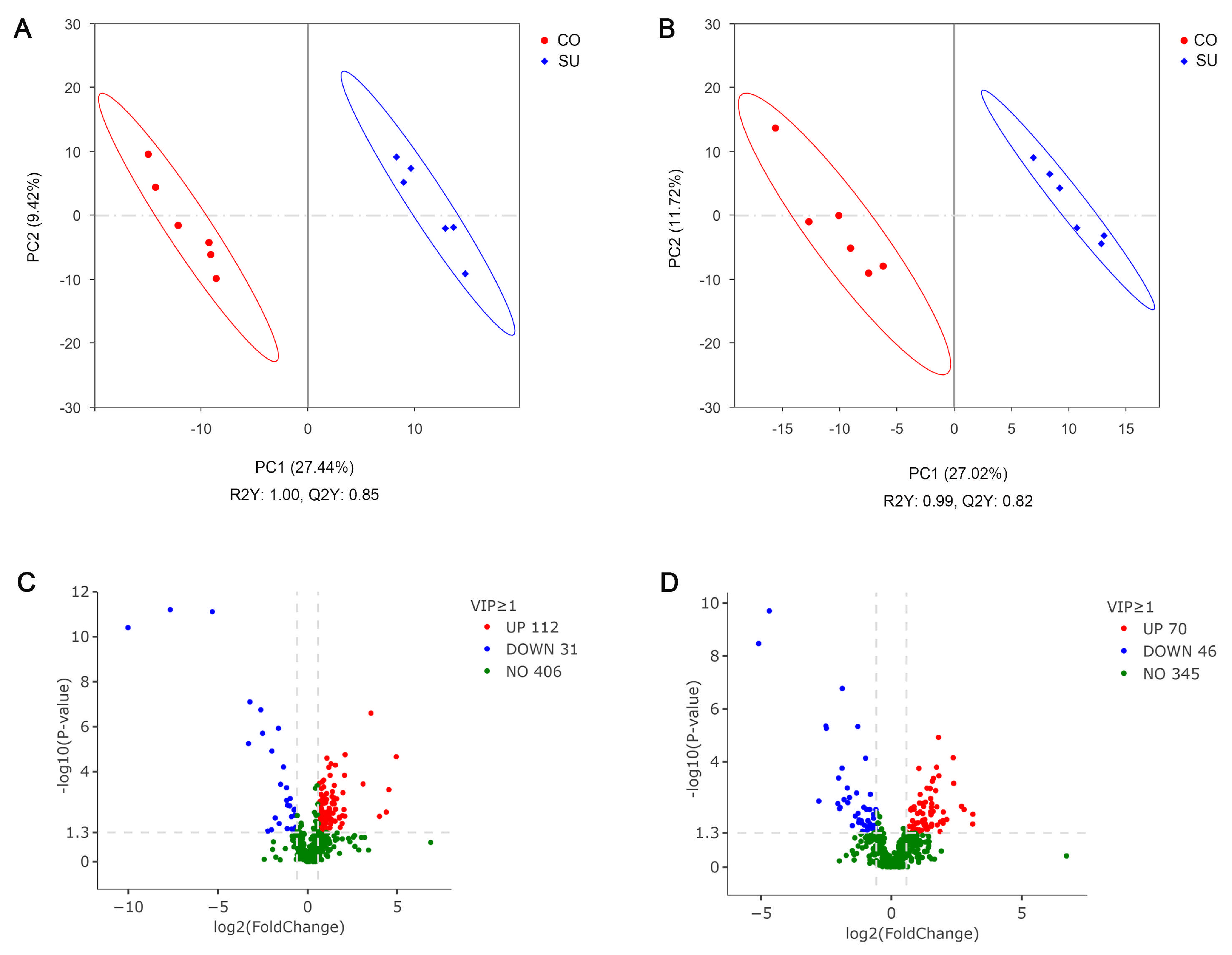

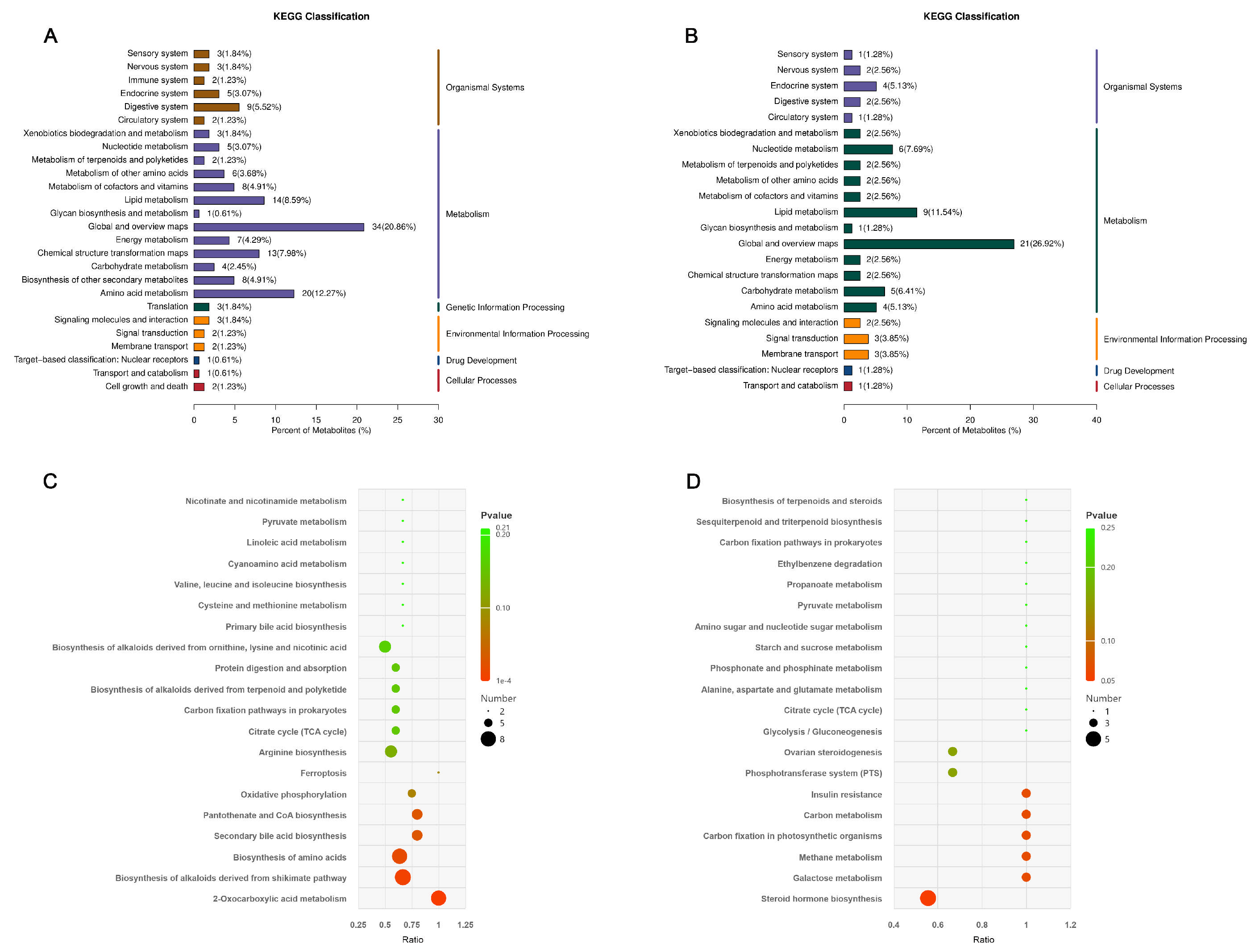

3.5. Analysis of Rumen Fluid Untargeted Metabolome

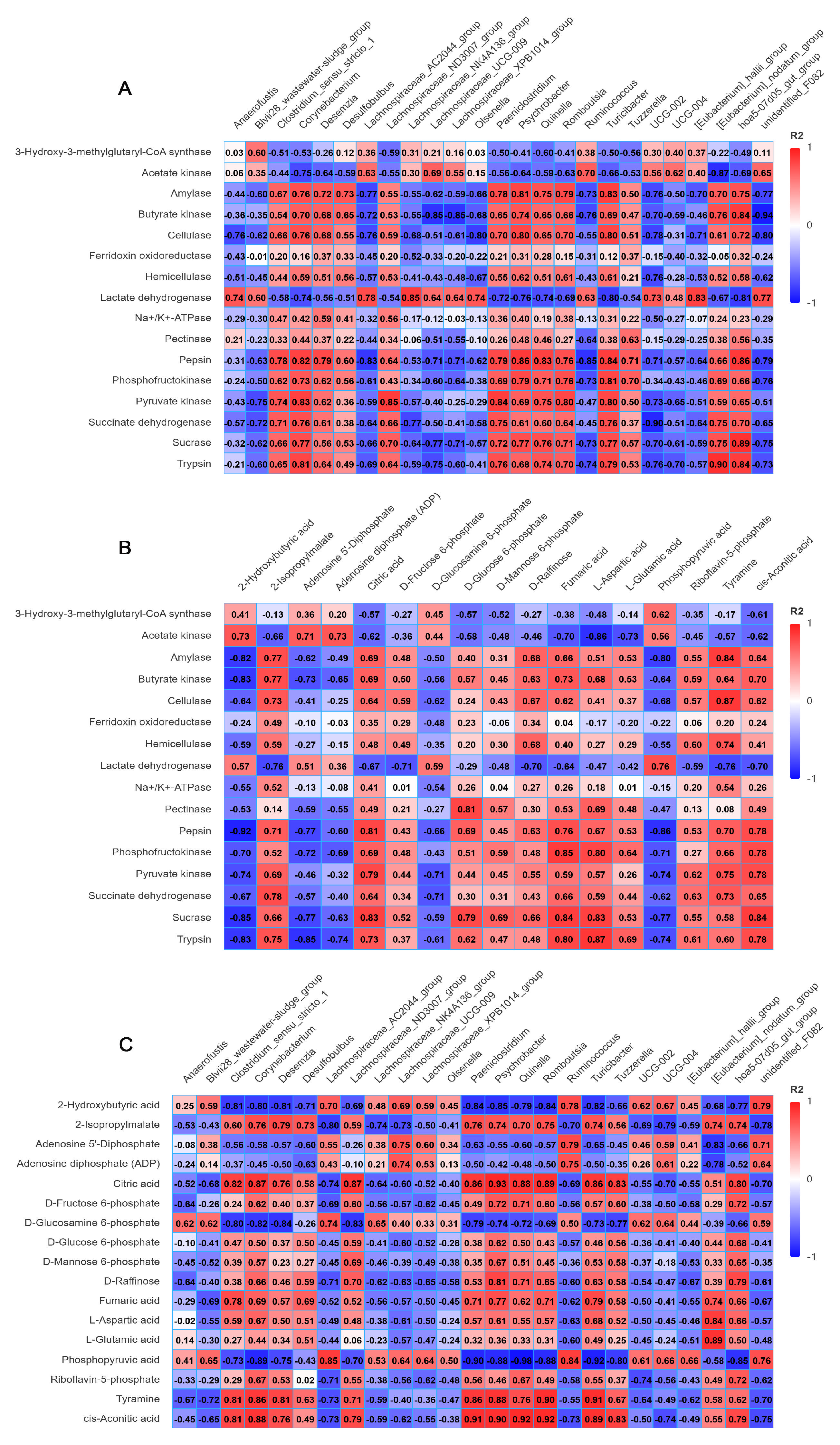

3.6. Correlation Analysis of Microbiota, Enzyme Activities and Metabolites in Rumen Fluid

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Growth Performance of Yak Calves

4.2. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on VFA Content of Yak Calves

4.3. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Activitives of Digestive Enzymes

4.4. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Rumen Microbial Community Composition

4.5. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Rumen Fluid’s Untargeted Metabolome

4.6. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Correlation of Microbiota, Enzyme Activities and Metabolites

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, B.Q.; Degen, A.A.; Han, X.D.; Hao, L.Z.; Huang, Y.Y.; Niu, J.Z.; Liu, S.J. Average daily gain and energy and nitrogen requirements of 4-month-old female yak calves. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 906440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Z.; Bai, B.Q.; Huang, Y.Y.; Degen, A.; Mi, J.D.; Xue, Y.F.; Hao, L.Z. Yaks are dependent on gut microbiota for survival in the environment of the Qinghai Tibet Plateau. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, R.J.; Ding, L.M.; Shang, Z.H.; Guo, X.H. The yak grazing system on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and its status. Rangel. J. 2008, 30, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohakare, J.D.; Südekum, K.H.; Pattanaik, A.K. Nutrition-induced changes of growth from birth to first calving and its impact on mammary development and first-lactation milk yield in dairy heifers: A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberon, F.; Amburgh, M.E.V. Lactation Biology Symposium: The effect of nutrient intake from milk or milk replacer of preweaned dairy calves on lactation milk yield as adults: A meta-analysis of current data. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.M.; Wang, Y.P.; Kreuzer, M.; Guo, X.S.; Mi, J.D.; Gou, Y.J.; Shang, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.W.; Wang, H.C.; et al. Seasonal variations in the fatty acid profile of milk from yaks grazing on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Dairy Res. 2013, 80, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M.; Bano, I.; Qazi, I.H.; Matra, M.; Wanapat, M. “The Yak”—A remarkable animal living in a harsh environment: An overview of its feeding, growth, production performance, and contribution to food security. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1086985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.A.; Baldwin, R.L.; Jesse, B.W. Sheep rumen metabolic development in response to age and dietary treatments. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 78, 1990–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Kim, D.; Roh, S. Growth of rumen papillae in weaned calves is associated with lower expression of insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins 2, 3, and 6. Anim. Sci. J. 2019, 90, 1287–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.L.; McLeod, K.R.; Klotz, J.L.; Heitmann, R.N. Rumen development, intestinal growth and hepatic metabolism in the pre-and postweaning ruminant. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, E55–E65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohe, T.T.; Schramm, H.; Parsons, C.L.M.; Tucker, H.L.M.; Enger, B.D.; Hardy, N.R.; Daniels, K.M. Form of calf diet and the rumen. I: Impact on growth and development. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 8486–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.Z.; Li, X.P.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Tan, Z.L.; Tang, S.X.; Zhou, C.S. Rumen development process in goats as affected by supplemental feeding v. grazing: Age-related anatomic development, functional achievement and microbial colonisation. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.M.; Bian, G.R.; Zhang, K.; Liu, N.; Yin, Y.Y.; Hou, Y.L.; Xie, F.; Zhu, W.Y.; Mao, S.Y.; Liu, J.H. Early-life ruminal microbiome-derived indole-3-carboxaldehyde and prostaglandin D2 are effective promoters of rumen development. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.D.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, N.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Jin, D. Different milk replacers alter growth performance and rumen bacterial diversity of dairy bull calves. Livest. Sci. 2020, 231, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, M.; Amanlou, H.; Khorvash, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Moshiri, B.; Ghaffari, M.H. Effect of different alfalfa hay levels on growth performance, rumen fermentation, and structural growth of Holstein dairy calves. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.H. Effects of Feeding Regimens on Growth Performance, Meat Quality, and the Underlying Metabolic Mechanisms in Yak Calves. Ph.D. Thesis, Qinghai University, Xining, China, 30 June 2025. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.P.; Cui, C.Z.; Qi, Y.P.; Mi, B.H.; Zhang, M.X.; Jiao, C.Y.; Zhu, C.N.; Wang, X.Y.; Hu, J.; Shi, B.G.; et al. Studies on fatty acids and microbiota characterization of the gastrointestinal tract of Tianzhu white yaks. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1508468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.G.; Xu, X.L.; Wang, Y.L.; Wei, L.; Li, N.; Liu, H.J.; Hu, L.Y.; Zhao, N.; et al. Targeted and untargeted metabolomics reveals meat quality in grazing yak during different phenology periods on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.H.; Hao, L.Z.; Sun, P.; Degen, A. Effect of substituting steam-flaked corn for course ground corn on in vitro digestibility, average daily gain, serum metabolites and ruminal volatile fatty acids, and bacteria diversity in growing yaks. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2023, 296, 115553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.B.; Broadhurst, D.; Begley, P.; Zelena, E.; Francis-McIntyre, S.; Anderson, N.; Brown, M.; Knowles, J.D.; Halsall, A.; Haselden, J.N.; et al. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 1060–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M.; Wang, Z.; Hu, R.; Peng, Q.; Zou, H.; Wang, L.; Xue, B. Discovery of the enrichment pathways and biomarkers using metabolomics techniques in unilateral and bilateral castration in yellow cattle. Pak. Vet. J. 2024, 44, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Nahashon, S.N.; Adefope, N.; Amenyenu, A.; Wright, D. Effects of dietary metabolizable energy and crude protein concentrations on growth performance and carcass characteristics of French guinea broilers. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.B.; Sun, G.M.; Dunzhu, L.S.; Li, X.; Zhaxi, L.S.; Zhaxi, S.L.; Ciyang, S.L.; Yangji, C.D.; Wangdui, B.S.; Pan, F.; et al. Effects of different dietary protein level on growth performance, rumen fermentation characteristics and plasma metabolomics profile of growing yak in the cold season. Animals 2023, 13, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raei, H.; Torshizi, M.A.K.; Sharafi, M.; Ahmadi, H. Improving seminal quality and reproductive performance in male broiler breeder by supplementation of camphor. Theriogenology 2021, 166, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.B.; Zhan, J.S.; Jia, H.B.; Jiang, H.Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhong, X.J.; Zhao, S.G.; Huo, J.H. Relationship between rumen microbial differences and phenotype traits among Hu sheep and crossbred offspring sheep. Animals 2024, 14, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.H.; Zhou, J.; Yang, X.T.; Shi, R.Z.; Liao, Y.C. Effects of forage-to-concentrate ratio during cold-season supplementation on growth performance, serum biochemistry, hormones, and antioxidant capacity in yak calves on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Animals 2025, 15, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Dadkhah, N.; Baghbanzadeh-Nobari, B.; Agha-Tehrani, A.; Eshraghi, M.; Imani, M.; Shiasi-Sardoabi, R.; Ghaffari, M.H. Effects of preweaning total plane of milk intake and weaning age on intake, growth performance, and blood metabolites of dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4212–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Bach, A.; Weary, D.M.; Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Invited review: Transitioning from milk to solid feed in dairy heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 885–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, I. Calf health from birth to weaning—An update. Ir. Vet. J. 2021, 74, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Montiel, F.; Ahuja, C. Body condition and suckling as factors influencing the duration of postpartum anestrus in cattle: A review. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2005, 85, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.R.; Wang, W.; Pitta, D.W.; Indugu, N.; Patra, A.K.; Wang, H.H.; Abrahamsen, F.; Hilaire, M.; Puchala, R. Characterization of the ruminal microbiota in sheep and goats fed different levels of tannin-rich Sericea lespedeza hay. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ocampo, R.; Montoya-Flores, M.D.; Herrera-Torres, E.; Pámanes-Carrasco, G.; Arceo-Castillo, J.I.; Valencia-Salazar, S.S.; Arango, J.; Aguilar-Pérez, C.F.; Ramírez-Avilés, L.; Solorio-Sánchez, F.J.; et al. Effect of chitosan and naringin on enteric methane emissions in crossbred heifers fed tropical grass. Animals 2021, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, J.W.; Degen, A.; Liu, H.S.; Cao, X.L.; Hao, L.Z.; Shang, Z.H.; Ran, T.; Long, R.J. A comparison of average daily gain, apparent digestibilities, energy balance, rumen fermentation parameters, and serum metabolites between yaks (Bos grunniens) and Qaidam cattle (Bos taurus) consuming diets differing in energy level. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 12, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.Y.; Guo, C.Y.; Gong, Y.; Sun, X.G.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.J.; Yang, H.J.; Cao, Z.J.; Li, S.L. Rumen fermentation, digestive enzyme activity, and bacteria composition between pre-weaning and post-weaning dairy calves. Animals 2021, 11, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgavi, D.P.; Kelly, W.J.; Janssen, P.H.; Attwood, G.T. Rumen microbial (meta) genomics and its application to ruminant production. Animal 2013, 7, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.G.; Orpin, C.G. Polysaccharide-degrading enzymes formed by three species of anaerobic rumen fungi grown on a range of carbohydrate substrates. Can. J. Microbiol. 1987, 33, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbakkers, P.J.M.; Harhangi, H.R.; Bosscher, M.W.; Hooft, M.M.C.; Keltjens, J.T.; Drift, C.; Vogels, G.D.; Camp, H.J.M. Beta-glucosidase in cellulosome of the anaerobic fungus Piromyces sp.strain E2 is a family 3 glycoside hydrolase. Biochem. J. 2003, 370, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Wei, W.Y.; Gao, J.J.; Jiang, X.M.; Che, L.Q.; Fang, Z.F.; Lin, Y.; Feng, B.; Zhuo, Y.; Hua, L.; et al. Effect of dietary fiber on reproductive performance, intestinal microorganisms and immunity of the sow: A review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, W.T.; Vu, V.V.; Span, E.A.; Phillips, C.M.; Marletta, M.A. Cellulose degradation by polysaccharide monooxygenases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.T.; Ma, T.; Tu, Y.; Ma, S.L.; Diao, Q.Y. Effects of circadian rhythm and feeding modes on rumen fermentation and microorganisms in Hu sheep. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.Y.; Feng, L.Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.B.; Chen, Y.G. Improved production of short-chain fatty acids from waste activated sludge driven by carbohydrate addition in continuous-flow reactors: Influence of SRT and temperature. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Q.; Guo, G.; Huo, W.J.; Pei, C.X.; Zhang, S.L.; Wang, H. Effects of concentrate-to-forage ratios and 2-methylbutyrate supplementation on ruminal fermentation, bacteria abundance and urinary excretion of purine derivatives in Chinese Simmental steers. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Mu, Y.Y.; Zhang, D.Q.; Lin, X.Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Hou, Q.L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.Y. Determination of microbiological characteristics in the digestive tract of different ruminant species. Microbiologyopen 2019, 8, e00769. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.F.; Mao, S.Y.; Zhu, W.Y. The bacterial and archaeal community structures and methanogenic potential of the cecal microbiota of goats fed with hay and high-grain diets. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2018, 111, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.L.; Xu, T.W.; Wang, X.G.; Geng, Y.Y.; Zhao, N.; Hu, L.Y.; Liu, H.J.; Kang, S.P.; Xu, S.X. Effect of dietary protein levels on dynamic changes and interactions of ruminal microbiota and metabolites in yaks on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 684340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchaar, C.; Lettat, A.; Hassanat, F.; Yang, W.Z.; Forster, R.J.; Petit, H.V.; Chouinard, P.Y. Eugenol for dairy cows fed low or high concentrate diets: Effects on digestion, ruminal fermentation characteristics, rumen microbial populations and milk fatty acid profile. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 178, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zou, H.W.; Wang, H.Z.; Wang, Z.S.; Wang, X.Y.; Ma, J.; Shah, A.M.; Peng, Q.H.; Xue, B.; Wang, L.Z.; et al. Dietary energy levels affect rumen bacterial populations that influence the intramuscular fat fatty acids of fattening yaks (Bos grunniens). Animals 2020, 10, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Kim, S.H.; Ramos, S.C.; Mamuad, L.L.; Son, A.R.; Yu, Z.T.; Lee, S.S.; Cho, Y.I.; Lee, S.S. Holstein and jersey steers differ in rumen microbiota and enteric methane emissions even fed the same total mixed ration. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 601061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Wu, D.T.; Wang, Z.S.; Shi, L.Y.; Hu, R.; Yue, Z.Q.; Che, L.; Zhong, W.; Ke, S.P.; Zhang, C.M.; et al. Effects of yeast β-glucan on fermentation parameters, microbial community structure, and rumen epithelial cell function in high-concentrate-induced yak rumen acidosis in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 314, 144441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Gao, H.M.; Qin, W.; Song, P.F.; Wang, H.J.; Zhang, J.J.; Liu, D.X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, T.Z. Marked seasonal variation in structure and function of gut microbiota in forest and alpine musk deer. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 699797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.A.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.B.; Kalwar, Q.; Liang, Z.Y.; Li, C.; Du, M.; Yan, P.; Long, R.J.; Han, J.L.; et al. Effects of dietary energy levels on rumen fermentation, microbial diversity, and feed efficiency of yaks (Bos grunniens). Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Penner, G.B.; Li, M.J.; Oba, M.; Guan, L.L. Changes in bacterial diversity associated with epithelial tissue in the beef cow rumen during the transition to a high-grain diet. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 5770–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Wang, Y.J.; Wei, M.L.; Liu, S.B.; Liu, K.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, R.Z.; Wang, Y.X.; Zheng, Y.J.; Fang, L.; et al. Effects of changes in rumen microbial adaptability on rumen fermentation and nutrient digestion in Horqin beef cattle during different seasons of grazing and supplementary feeding. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, B.R.; Lourencon, R.V.; Nagaraju, I.; Pitta, D.; Ismael, H.; Abdo, H.; Chaudhary, S.; Hilaire, M.; Kanyi, V.; Solaiman, S.; et al. The effect of the forage-to-concentrate ratio of the total mixed ration on ruminal microbiota changes in Alpine dairy goats. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 103, skaf260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, J.T.; Luo, Y.F.; Liu, D.; Zheng, H.J.; Wang, J.Q.; Dong, Z.Y.; Hu, S.N.; Huang, L. Metatranscriptomic analyses of plant cell wall polysaccharide degradation by microorganisms in the cow rumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Teng, Z.W.; Meng, Q.; Liu, S.; Yuan, L.P.; Fu, T.; Zhang, N.N.; Gao, T.Y. Dynamics of fermentation parameters and bacterial community in rumen of calves during dietary protein oscillation. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, W.; Cheng, H.J.; Hu, X.; Song, E.L.; Jiang, F.G. Capsaicin modulates ruminal fermentation and bacterial communities in beef cattle with high-grain diet-induced subacute ruminal acidosis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, M.J.; Conant, G.C.; Cockrum, R.R.; Austin, K.J.; Truong, H.; Becchi, M.; Lamberson, W.R.; Cammack, K.M. Diet alters both the structure and taxonomy of the ovine gut microbial ecosystem. DNA Res. 2014, 21, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, M.P.; Diao, Q.Y.; Tu, Y. Saponin-induced shifts in the rumen microbiome and metabolome of young cattle. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.G.; Pan, X.H.; Jiang, L.S.; Guo, Y.M.; Xiong, B.H. GC-MS analysis of the ruminal metabolome response to thiamine supplementation during high grain feeding in dairy cows. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Tannahill, G.M.; Curtis, A.M.; Adamik, J.; Palsson-McDermott, E.M.; McGettrick, A.F.; Goel, G.; Frezza, C.; Bernard, N.J.; Kelly, B.; Foley, N.H.; et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature 2013, 496, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.Q.; Li, H.; Huang, N.; Zhou, X.H.; Tian, J.Q.; Li, T.J.; Wu, J.; Tian, Y.N.; Yin, Y.L.; Yao, K. Alpha-ketoglutarate suppresses the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory pathway and enhances the PXR-regulated detoxification pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 102974–102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.X.; Wei, J.; Deng, G.; Hu, A.; Sun, P.Y.; Zhao, X.L.; Song, B.L.; Luo, J. Delivery of low-density lipoprotein from endocytic carriers to mitochondria supports steroidogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, H.L.; Hu, L.R.; Zhang, G.X.; Lu, H.B.; Luo, H.P.; Zhao, S.J.; Zhu, H.B.; Wang, Y.C. Characterization of the microbial communities along the gastrointestinal tract in crossbred cattle. Animals 2022, 12, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amenyogbe, E.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.L.; Lu, X.Y.; Lin, M.D.; Lin, A.Y. A review on sex steroid hormone estrogen receptors in mammals and fish. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 2020, 5386193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.S.; Wanapat, M.; Yan, T.H.; Hou, F.J. Altitude influences microbial diversity and herbage fermentation in the rumen of yaks. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.F.; Wu, Q.; Dai, J.Y.; Zhang, S.N.; Wei, F.W. Evidence of cellulose metabolism by the giant panda gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17714–17719. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.Q.; Zhang, R.; Jiao, Y.L.; Li, M.F.; Xu, Z.H.; Sun, L.; Liu, W.T.; Qiu, Y.Q.; Li, F.M.; Li, X.B.; et al. Effects of 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole and cobalt supplementation in high-concentrate diets on rumen fermentation and microorganisms and ruminal metabolome in sheep. BMC Vet. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

| Feed Composition | Content |

|---|---|

| Oat hay | 30.00 |

| Corn | 37.10 |

| Wheat bran | 8.40 |

| Soybean meal | 10.50 |

| Canola meal | 8.40 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.05 |

| CaCO3 | 1.05 |

| NaHCO3 | 0.70 |

| NaCl | 2.10 |

| Premix 1 | 0.70 |

| Total | 100.00 |

| Nutrient levels 2 | |

| Metabolic energy 3, MJ/kg | 9.02 |

| Crude protein | 12.78 |

| Ether extract | 1.68 |

| Ash | 7.79 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 29.03 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 18.87 |

| Ca | 0.51 |

| P | 0.54 |

| Parameters | CO | SU | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial wither height, cm | 78.33 ± 4.68 | 82.33 ± 4.59 | 0.166 |

| Final wither height, cm | 92.17 ± 2.23 a | 85.50 ± 1.87 b | <0.001 |

| Initial body length, cm | 76.50 ± 4.76 | 82.00 ± 6.78 | 0.135 |

| Final body length, cm | 89.83 ± 6.31 | 86.17 ± 7.19 | 0.370 |

| Initial chest circumference, cm | 111.33 ± 6.12 | 111.83 ± 4.96 | 0.880 |

| Final chest circumference, cm | 130.33 ± 3.88 a | 115.33 ± 7.87 b | 0.002 |

| Initial weight, kg | 67.43 ± 7.44 | 69.63 ± 5.68 | 0.577 |

| Final weight, kg | 105.93 ± 8.74 a | 79.48 ± 6.89 b | <0.001 |

| Total weight gain, kg | 38.49 ± 4.51 a | 9.85 ± 4.03 b | <0.001 |

| ADG, kg/d | 0.32 ± 0.04 a | 0.08 ± 0.03 b | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Ma, W.; Malik, M.I.; Shah, A.M.; Liu, A.; Hu, G.; Jing, J.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Growth Performance, Enzyme Activity, Rumen Microbial Diversity and Metabolomic Profiles in Yak Calves. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010081

Wang H, Ma W, Malik MI, Shah AM, Liu A, Hu G, Jing J, Li H, Huang Y, Zhang Q, et al. Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Growth Performance, Enzyme Activity, Rumen Microbial Diversity and Metabolomic Profiles in Yak Calves. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Hongli, Wanhao Ma, Muhammad Irfan Malik, Ali Mujtaba Shah, Aixin Liu, Guangwei Hu, Jianwu Jing, Hongkang Li, Yayu Huang, Qunying Zhang, and et al. 2026. "Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Growth Performance, Enzyme Activity, Rumen Microbial Diversity and Metabolomic Profiles in Yak Calves" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010081

APA StyleWang, H., Ma, W., Malik, M. I., Shah, A. M., Liu, A., Hu, G., Jing, J., Li, H., Huang, Y., Zhang, Q., Zhou, J., Bai, B., Yang, Y., Wang, Z., Zhang, J., & Hao, L. (2026). Effects of Different Feeding Methods on Growth Performance, Enzyme Activity, Rumen Microbial Diversity and Metabolomic Profiles in Yak Calves. Microorganisms, 14(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010081