Screening and Action Mechanism of Biological Control Strain Bacillus atrophaeus F4 Against Maize Anthracnose

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Strain Culture

2.2. Sample Collection and Bacterial Strain Isolation

2.3. Greenhouse Screening of Biocontrol Bacteria

2.4. Strain Identification and Genome Sequencing

2.5. Biocontrol Experiment on Detached Maize Leaves

2.6. Conidial Germination Inhibition Assay

2.7. Extraction of Lipopeptides and MALDI-TOF MS Analysis

2.8. Microscopy Techniques

2.9. Determination of Chitin Content in Hyphal Cell Walls

2.10. Plate Confrontation Assay

2.11. Motility, Biofilm, and Extracellular Enzymes Assays

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. In Vivo Screening and Identification of Biocontrol Strains Against Maize Anthracnose

3.2. Complete Genome Sequencing and Analysis of B. atrophaeus F4

3.3. F4 Lipopeptide Extract Exhibits Biocontrol Activity Against Maize Anthracnose in Detached Leaves

3.4. Inhibitory Effects of Lipopeptide Extract from B. atrophaeus F4 on Pathogenic Fungal Hyphae

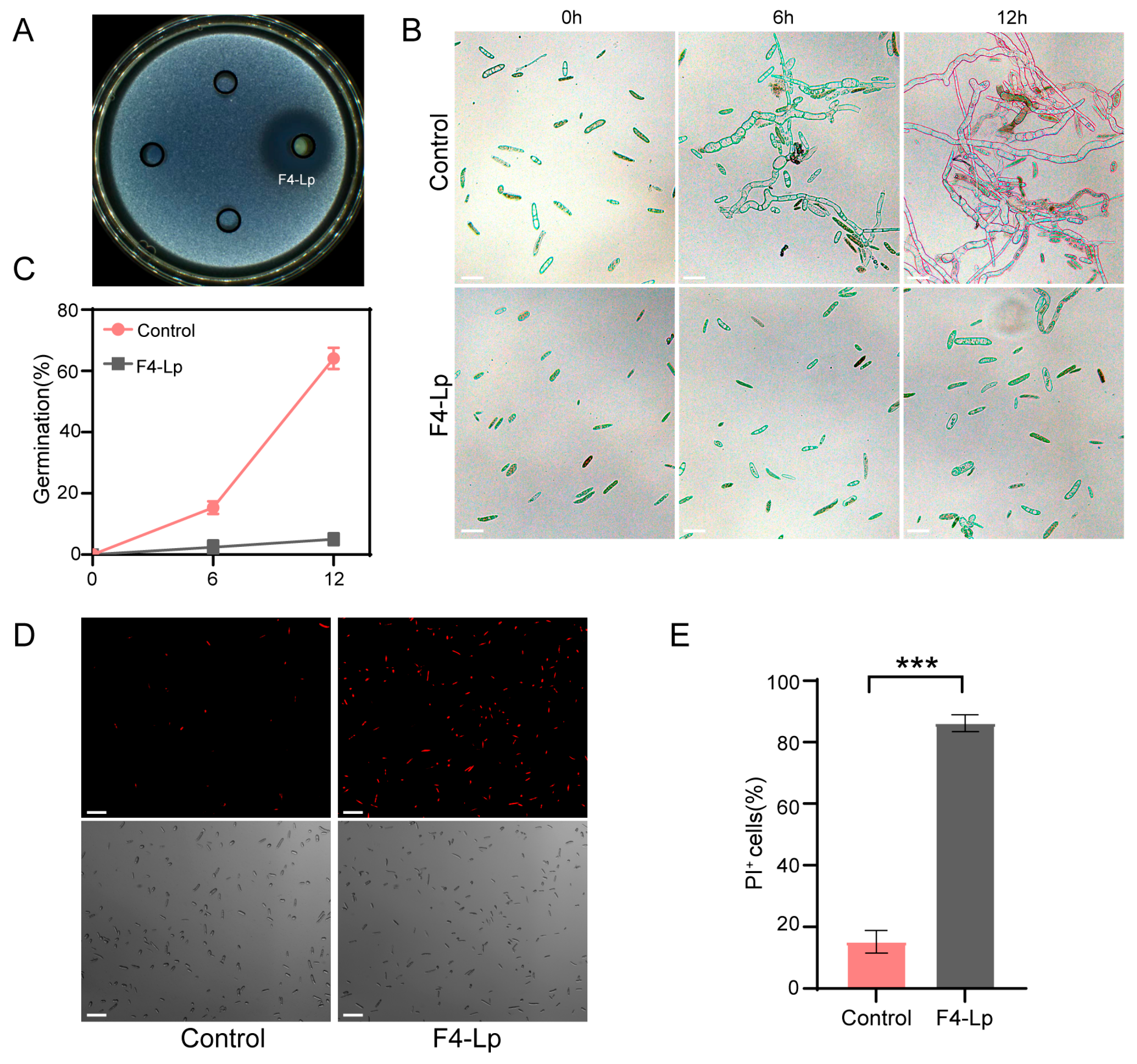

3.5. Inhibitory Effects of Lipopeptide Extract from B. atrophaeus F4 on Pathogenic Conidial Germination

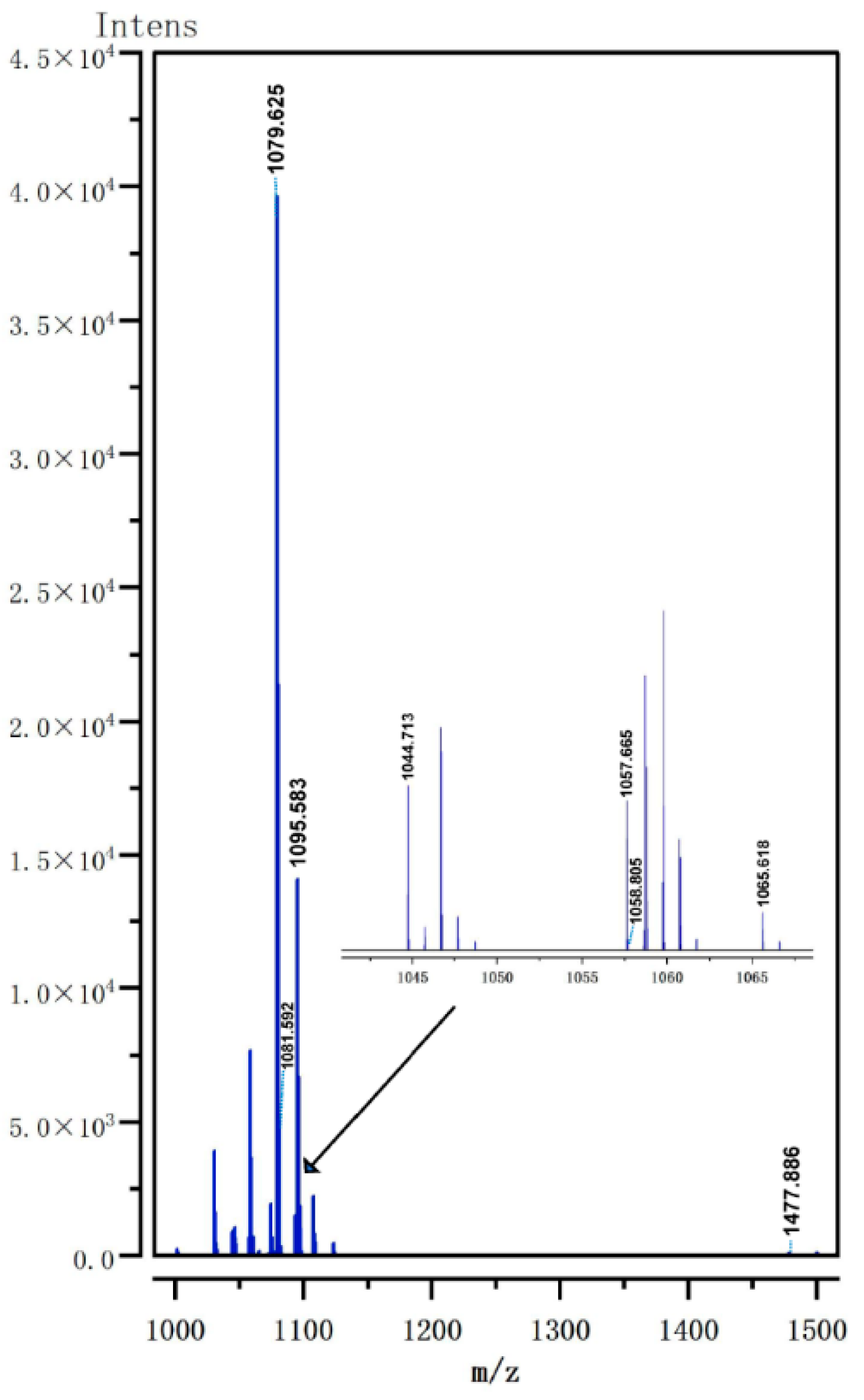

3.6. Analysis of Lipopeptide Extract Components by MALDI-TOF MS

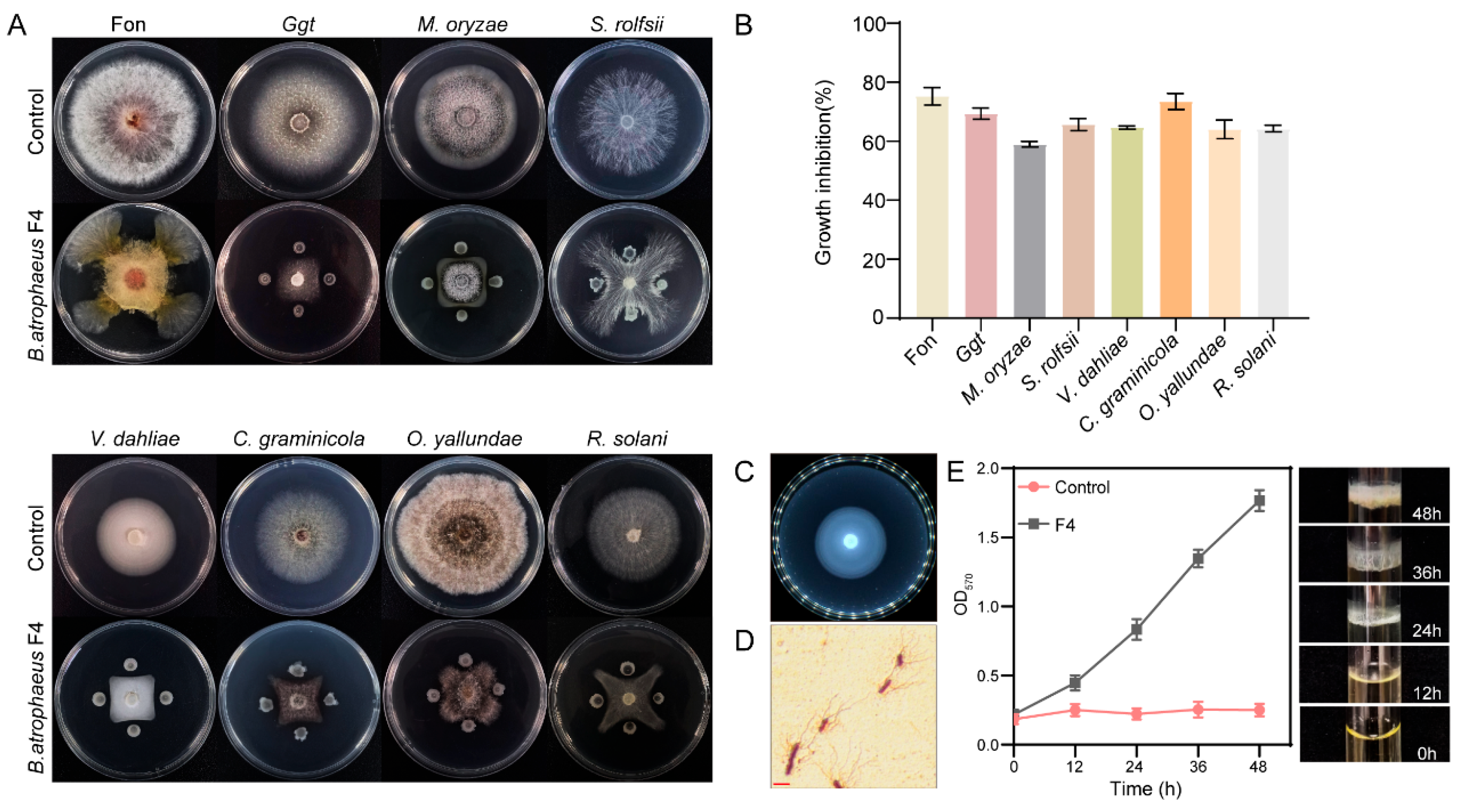

3.7. Antifungal Spectrum and Other Biocontrol-Related Characteristics of B. atrophaeus F4

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canton, H. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations—FAO. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom, G.C.; Nicholson, R.L. The biology of corn anthracnose: Knowledge to exploit for improved management. Plant Dis. 1999, 83, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, A. Corn anthracnose leaf blight and stalk rot. Annu. Corn Sorghum Res. Conf. 1976, 31, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- White, D.; Yanney, J.; Natti, T. Anthracnose stalk rot. Annu. Corn Sorghum Res. Conf. 1979, 34, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany, L.H.; Gilman, J.C. Species of Colletotrichum from legumes. Mycologia 1954, 46, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukno, S.A.; Sanz-Martín, J.M.; González-Fuente, M.; Hiltbrunner, J.; Thon, M.R. First report of anthracnose stalk rot of maize caused by Colletotrichum graminicola in Switzerland. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.X.; Guo, C.; Yang, Z.H.; Sun, S.L.; Zhu, Z.D.; Wang, X.M. First report of anthracnose leaf blight of maize caused by Colletotrichum graminicola in China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Martín, J.; Postigo, V.; Mateos, A.; Albrecht, B.; Munkvold, G.; Thon, M.; Sukno, S. First report of Colletotrichum graminicola causing maize anthracnose stalk rot in the Alentejo Region, Portugal. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogério, F.; Taati, A.; García-Rodríguez, P.; Baroncelli, R.; Thon, M.R.; Santiago, R.; Revilla, P.; Sukno, S.A. First Report of Colletotrichum graminicola Causing Maize Anthracnose in Galicia, Northwestern Spain. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Sánchez, S.; Rodríguez-Mónaco, L.; Langmaier, C.; Baroncelli, R.; Thon, M.R.; Buhiniček, I.; Sukno, S.A. First Report of Colletotrichum graminicola Causing Maize Anthracnose in Austria. Plant Dis. 2025, 109, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogério, F.; Baroncelli, R.; Cuevas-Fernández, F.B.; Becerra, S.; Crouch, J.; Bettiol, W.; Azcárate-Peril, M.A.; Malapi-Wight, M.; Ortega, V.; Betran, J.; et al. Population genomics provide insights into the global genetic structure of Colletotrichum graminicola, the causal agent of maize anthracnose. Mbio 2023, 14, e02878-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, D.S.; Wise, K.A.; Sisson, A.J.; Allen, T.W.; Bergstrom, G.C.; Bissonnette, K.M.; Bradley, C.A.; Byamukama, E.; Chilvers, M.I.; Collins, A.A.; et al. Corn yield loss estimates due to diseases in the United States and Ontario, Canada, from 2016 to 2019. Plant Health Prog. 2020, 21, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, J.A.; Clarke, B.B.; Hillman, B.I. Unraveling evolutionary relationships among the divergent lineages of Colletotrichum causing anthracnose disease in turfgrass and corn. Phytopathology 2006, 96, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Xia, X.; Mei, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Duan, C.; Liu, W. Genome sequence resource of a Colletotrichum graminicola field strain from China. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2023, 36, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Martín, J.M.; Pacheco-Arjona, J.R.; Bello-Rico, V.; Vargas, W.A.; Monod, M.; Díaz-Mínguez, J.M.; Thon, M.R.; Sukno, S.A. A highly conserved metalloprotease effector enhances virulence in the maize anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum graminicola. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oide, S.; Moeder, W.; Krasnoff, S.; Gibson, D.; Haas, H.; Yoshioka, K.; Turgeon, B.G. NPS6, encoding a nonribosomal peptide synthetase involved in siderophore-mediated iron metabolism, is a conserved virulence determinant of plant pathogenic ascomycetes. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2836–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Silva, A.; Devasahayam, B.R.F.; Aliyeva-Schnorr, L.; Glienke, C.; Deising, H.B. The serine-threonine protein kinase Snf1 orchestrates the expression of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes and is required for full virulence of the maize pathogen Colletotrichum graminicola. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2024, 171, 103876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, J.; Huang, H.; Jia, J.; Yuan, M.; Xiao, S.; Xue, C. Highly efficient gene knockout system in the maize pathogen Colletotrichum graminicola using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT). J. Microbiol. Methods 2023, 212, 106812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Yang, J.; Ding, J.; Duan, C.; Zhao, W.; Peng, Y.-L.; Bhadauria, V. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of large chromosomal segments identifies a minichromosome modulating the Colletotrichum graminicola virulence on maize. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 245, 125462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Gao, X.; Han, T.; Mohammed, M.T.; Yang, J.; Ding, J.; Zhao, W.; Peng, Y.-L.; Bhadauria, V. Molecular genetics of anthracnose resistance in maize. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, P. Influence of inoculum from buried and surface corn residues on the incidence of corn anthracnose. Phytopathology 1985, 75, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, P.E. Spread of corn anthracnose from surface residues in continuous corn and corn-soybean rotation plots. Phytopathology 1988, 78, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirak-Peterson, J.C.; Esker, P.D. Tillage, crop rotation, and hybrid effects on residue and corn anthracnose occurrence in Wisconsin. Plant Dis. 2011, 95, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Jackson, E.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic acid and jasmonic acid in plant immunity. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, Z.; Christensen, S.A.; Yan, Y.; He, Y.; Borrego, E.; Kolomiets, M.V. Green leaf volatiles and jasmonic acid enhance susceptibility to anthracnose diseases caused by Colletotrichum graminicola in maize. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djonovic, S.; Vargas, W.A.; Kolomiets, M.V.; Horndeski, M.; Wiest, A.; Kenerley, C.M. A proteinaceous elicitor Sm1 from the beneficial fungus Trichoderma virens is required for induced systemic resistance in maize. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchamp, C.; Glauser, G.; Mauch-Mani, B. Root inoculation with Pseudomonas putida KT2440 induces transcriptional and metabolic changes and systemic resistance in maize plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.R.; Pascholati, S. Saccharomyces cerevisiae protects maize plants, under greenhouse conditions, against Colletotrichum graminicola. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 1992, 99, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, M.; Fokkema, N. Phyllosphere yeasts antagonize penetration from appressoria and subsequent infection of maize leaves by Colletotrichum graminicola. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 1985, 91, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.Z.; Ahmad, K.; Kutawa, A.B.; Siddiqui, Y.; Saad, N.; Hun, T.G.; Hata, E.M.; Hossain, I. Biology, diversity, detection and management of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum causing vascular wilt disease of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus): A review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Guo, X.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D. Activity of fengycin and iturin A isolated from Bacillus subtilis Z-14 on Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici and soil microbial diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 682437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.A.; Talbot, N.J. Under pressure: Investigating the biology of plant infection by Magnaporthe oryzae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Mao, X.; Zhang, G.; He, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, L. Antifungal activity and mechanism of physcion against Sclerotium rolfsii, the causal agent of peanut southern blight. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 15601–15612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umer, M.J.; Zheng, J.; Yang, M.; Batool, R.; Abro, A.A.; Hou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gebremeskel, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Insights to Gossypium defense response against Verticillium dahliae: The cotton cancer. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanauskienė, J.; Gaurilčikienė, I.; Supronienė, S. Effects of fungicides on the occurrence of winter wheat eyespot caused by fungi Oculimacula acuformis and O. yallundae. Crop Prot. 2016, 90, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; Pujol, M.; Metraux, J.P.; Gonzalez-Garcia, V.; Bolton, M.D.; Borrás-Hidalgo, O. Tobacco leaf spot and root rot caused by Rhizoctonia solani Kühn. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordzieke, D.E.; Sanken, A.; Antelo, L.; Raschke, A.; Deising, H.B.; Pöggeler, S. Specialized infection strategies of falcate and oval conidia of Colletotrichum graminicola. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 133, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xiao, S.; Xu, J.; Lu, K.; Xue, C.; Chen, J. Occurrence condition and chemical control of maize eyespot in Liaoning Province. J. Maize Sci. 2016, 24, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Rong, W.; Zhang, Z. The pathogen-induced MATE gene TaPIMA1 is required for defense responses to Rhizoctonia cerealis in wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M.; Bickhart, D.M.; Behsaz, B.; Gurevich, A.; Rayko, M.; Shin, S.B.; Kuhn, K.; Yuan, J.; Polevikov, E.; Smith, T.P.L.; et al. metaFlye: Scalable long-read metagenome assembly using repeat graphs. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhou, C.; Tao, L. Computational advances in biosynthetic gene cluster discovery and prediction. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 79, 108532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukno, S.A.; García, V.M.; Shaw, B.D.; Thon, M.R. Root infection and systemic colonization of maize by Colletotrichum graminicola. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Qiang, R.; Zhou, Z.; Pan, Y.; Yu, S.; Yuan, W.; Cheng, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, J.; et al. Biocontrol and action mechanism of Bacillus subtilis lipopeptides’ fengycins against Alternaria solani in potato as assessed by a transcriptome analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 861113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vater, J.; Kablitz, B.; Wilde, C.; Franke, P.; Mehta, N.; Cameotra, S.S. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry of lipopeptide biosurfactants in whole cells and culture filtrates of Bacillus subtilis C-1 isolated from petroleum sludge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 6210–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkić, I.; Stanković, S.; Nišavić, M.; Petković, M.; Ristivojević, P.; Fira, D.; Berić, T. The profile and antimicrobial activity of Bacillus lipopeptide extracts of five potential biocontrol strains. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 925, Correction in Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, G. A LysR-like Transcriptional Regulator DsfB Is Required for the Daughter Cell Separation in Bacillus cereus 0–9. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 8148–8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou HaiEn, Z.H.; Tao NengGuo, T.N.; Jia Lei, J.L. Antifungal activity of citral, octanal and α-terpineol against Geotrichum citri-aurantii. Food Control 2014, 37, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OuYang, Q.; Duan, X.; Li, L.; Tao, N. Cinnamaldehyde exerts its antifungal activity by disrupting the cell wall integrity of Geotrichum citri-aurantii. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Meng, Y.; Mai, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Gong, P.-X.; Zhang, M.-Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K.; Zhu, Y. Discovery of Novel Natural Maltol-Based Derivatives as Potential Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 27740–27750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Wei, L.; Zhao, H.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Ding, H. Perception of the biocontrol potential and palmitic acid biosynthesis pathway of Bacillus subtilis H2 through merging genome mining with chemical analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 4834–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Liu, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, G. Isocitrate dehydrogenase of Bacillus cereus is involved in biofilm formation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, F.; Li, C.; Wang, G. Production of extracellular amylase contributes to the colonization of Bacillus cereus 0–9 in wheat roots. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Su, C.; Gong, G.; Wang, P.; Yu, Z. Isolation and characterization of lipopeptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus subtilis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Shang, Q.; Nicolaisen, M.; Zeng, R.; Gao, S.; Gao, P.; Song, Z.; Dai, F.; Zhang, J. Biocontrol potential of rhizospheric Bacillus strains against Sclerotinia minor jagger causing lettuce drop. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.; Keharia, H. Characterization of fungal antagonistic bacilli isolated from aerial roots of banyan (Ficus benghalensis) using intact-cell MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (ICMS). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, W. Identification of antifungal peptides from Bacillus subtilis Bs-918. Anal. Lett. 2014, 47, 2891–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.B.; de Oliveira Cruz, J.; Geraldo, L.C.; Dias, E.G.; Queiroz, P.R.M.; Monnerat, R.G.; Borges, M.; Blassioli-Moraes, M.C.; Blum, L.E.B. Detection and evaluation of volatile and non-volatile antifungal compounds produced by Bacillus spp. strains. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 275, 127465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Rodriguez, E.; Moreno-Ulloa, A.; Castro-Longoria, E.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; de Los Santos-Villalobos, S. Integrated omics approaches for deciphering antifungal metabolites produced by a novel Bacillus species, B. cabrialesii TE3T, against the spot blotch disease of wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum). Microbiol. Res. 2021, 251, 126826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, A.P.D.C.; Ferreira, H.D.S.; Silva, Y.A.D.; Silva, R.R.D.; Lima, C.V.D.; Sarubbo, L.A.; Luna, J.M. Biosurfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis UCP 1533 isolated from the Brazilian semiarid region: Characterization and antimicrobial potential. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliard, G.; Demortier, T.; Boubsi, F.; Jijakli, M.H.; Ongena, M.; De Clerck, C.; Deleu, M. Deciphering the distinct biocontrol activities of lipopeptides fengycin and surfactin through their differential impact on lipid membranes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2024, 239, 113933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewer, D.P.; Jokela, J.; Heinilä, L.; Aesoy, R.; Sivonen, K.; Galica, T.; Hrouzek, P.; Herfindal, L. Chemical diversity and cellular effects of antifungal cyclic lipopeptides from cyanobacteria. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, F.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.; Huang, L.; Li, K. Antifungal lipopeptides from the marine Bacillus amyloliquefaciens HY2–1: A potential biocontrol agent exhibiting in vitro and in vivo antagonistic activities against Penicillium digitatum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 287, 138583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Yang, R.-D.; Cao, H.; Song, G.-N.; Cui, F.; Zhou, S.; Yuan, J.; Qi, H.; Wang, J.-D.; Chen, J. Microscopic and Transcriptomic Analyses to elucidate antifungal mechanisms of Bacillus velezensis TCS001 Lipopeptides against Botrytis cinerea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 17405–17416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Loon, L.C.; Rep, M.; Pieterse, C.M. Significance of inducible defense-related proteins in infected plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Yang, P.; Liu, Y.; Tabl, K.M.; Guo, M.; Zhang, J.; Wu, A.; Liao, Y.; Huang, T.; He, W. Iturin and fengycin lipopeptides inhibit pathogenic Fusarium by targeting multiple components of the cell membrane and their regulative effects in wheat. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 2184–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; Xiao, H. Recent advances in antimicrobial lipopeptide fengycin secreted by Bacillus: Structure, biosynthesis, antifungal mechanisms, and potential application in food preservation. Food Chem. 2025, 489, 144937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpathong, W.; Intra, B.; Euanorasetr, J.; Wanapaisan, P. Biosurfactant-producing Bacillus velezensis PW192 as an anti-fungal biocontrol agent against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Colletotrichum musae. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Wang, H.; Tan, Z.; Xuan, Z.; Dahar, G.Y.; Li, Q.X.; Miao, W.; Liu, W. Antifungal mechanism of bacillomycin D from Bacillus velezensis HN-2 against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Penz. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 163, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaccione, D.G.; Vaillancourt, L.J.; Hanau, R.M. Conidial dimorphism in Colletotrichum graminicola. Mycologia 1989, 81, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venard, C.; Kulshrestha, S.; Sweigard, J.; Nuckles, E.; Vaillancourt, L. The role of a fadA ortholog in the growth and development of Colletotrichum graminicola in vitro and in planta. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2008, 45, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belisário, R.; Robertson, A.E.; Vaillancourt, L.J. Maize anthracnose stalk rot in the genomic era. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 2281–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Sugui, J.A.; Steinberg, G.; Deising, H.B. A chitin synthase with a myosin-like motor domain is essential for hyphal growth, appressorium differentiation, and pathogenicity of the maize anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum graminicola. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlali, R.; Ezrari, S.; Radouane, N.; Kenfaoui, J.; Esmaeel, Q.; El Hamss, H.; Belabess, Z.; Barka, E.A. Biological control of plant pathogens: A global perspective. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedharan, S.M.; Rishi, N.; Singh, R. Microbial lipopeptides: Properties, mechanics and engineering for novel lipopeptides. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 271, 127363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.F.; Pires, E.B.; Sousa, O.F.; Alves, G.B.; Viteri Jumbo, L.O.; Santos, G.R.; Maia, L.J.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Smagghe, G.; Perino, E.H.B.; et al. A novel neotropical Bacillus siamensis strain inhibits soil-borne plant pathogens and promotes soybean growth. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Full Name | Disease Caused |

|---|---|---|

| Fon | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum | watermelon Fusarium wilt [30] |

| Ggt | Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici | wheat take-all [31] |

| Monzae | Magnaporthe oryzae | rice blast [32] |

| S. rolfsii | Sclerotium rolfsii | peanut stem rot [33] |

| V. dahliae | Verticillium dahliae | verticillium wilt [34] |

| C. graminicola | Colletotrichum graminicola | maize anthracnose [20] |

| O. vallundae | Oculimacula vallindae | sharp eyespot [35] |

| R. solani | Rhizoctonia solani | seedling blight [36] |

| Treatment | Disease Index | Disease Incidence | Control Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| LB medium (negative control) | 0.00 | 0.00 | _ |

| C. graminicola (positive control) | 0.89 | 95.00% | _ |

| C. graminicola + F4 Broth | 0.18 | 20.00% | 79.78% |

| C. graminicola + F4-S | 0.20 | 22.00% | 77.53% |

| Region | Location (bp) | Predicted BGC Type(s) | Most Similar Known Cluster | Similarity a | Evidence Level b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 205,818–252,822 | NRPS, Sactipeptide, Ranthipeptide | Sporulation killing factor | High | Strong |

| 2 | 374,774–440,187 | NRPS | Surfactin | High | Strong |

| 3 | 1,162,693–1,183,514 | Terpene | - c | - | Putative |

| 4 | 1,777,754–1,893,259 | transAT-PKS, T3PKS, NRPS | Bacillaene | High | Strong |

| 5 | 1,994,803–2,141,863 | NRPS, Betalactone, transAT-PKS | Fengycin | High | Strong |

| 6 | 2,153,077–2,174,966 | Terpene | - | - | Putative |

| 7 | 2,246,856–2,286,953 | T3PKS | 1-Carbapen-2-em-3-carboxylic acid | low | Weak/Putative |

| 8 | 3,139,212–3,191,077 | NRP-Metallophore, NRPS | Bacillibactin | High | Strong |

| 9 | 3,204,298–3,234,401 | Azole-containing RIPP | - | - | Putative |

| 10 | 3,693,340–3,714,949 | Sactipeptide | Subtilosin A | High | Strong |

| 11 | 3,952,188–3,973,886 | Epipeptide | - | - | Putative |

| No. | Mass Peak (m/z) | Family | Assignment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1044.713 | C14 surfactin | [M + Na]+ | [54] |

| 2 | 1057.665 | C15 iturin | [M + H]+ | [55] |

| 3 | 1058.805 | C15 surfactin | [M + Na]+ | [55] |

| 4 | 1065.618 | C14 iturin | [M + Na]+ | [56] |

| 5 | 1079.625 | C15 iturin | [M + Na]+ | [55] |

| 6 | 1081.592 | C14 iturin | [M + K]+ | [54] |

| 7 | 1095.583 | C15 iturin | [M + K]+ | [54] |

| 8 | 1477.886 | C15 fengycin B | [M + H]+ | [57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, P.; Xi, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Huang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Reheman, N.; Liu, F. Screening and Action Mechanism of Biological Control Strain Bacillus atrophaeus F4 Against Maize Anthracnose. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010047

Wang P, Xi Y, Liu K, Wang J, Huang Q, Wang H, Wang S, Wang G, Reheman N, Liu F. Screening and Action Mechanism of Biological Control Strain Bacillus atrophaeus F4 Against Maize Anthracnose. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Pengfei, Yingying Xi, Ke Liu, Jiaqi Wang, Qiubin Huang, Haodong Wang, Shaowei Wang, Gang Wang, Nuerguli Reheman, and Fengying Liu. 2026. "Screening and Action Mechanism of Biological Control Strain Bacillus atrophaeus F4 Against Maize Anthracnose" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010047

APA StyleWang, P., Xi, Y., Liu, K., Wang, J., Huang, Q., Wang, H., Wang, S., Wang, G., Reheman, N., & Liu, F. (2026). Screening and Action Mechanism of Biological Control Strain Bacillus atrophaeus F4 Against Maize Anthracnose. Microorganisms, 14(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010047