Effects of Left-Displaced Abomasum on the Rumen Microbiota of Dairy Cows

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Surgical Treatment of LDA in Cows

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing of Rumen Contents

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Bacterial Diversity

3.1.1. Comparison of OTUs

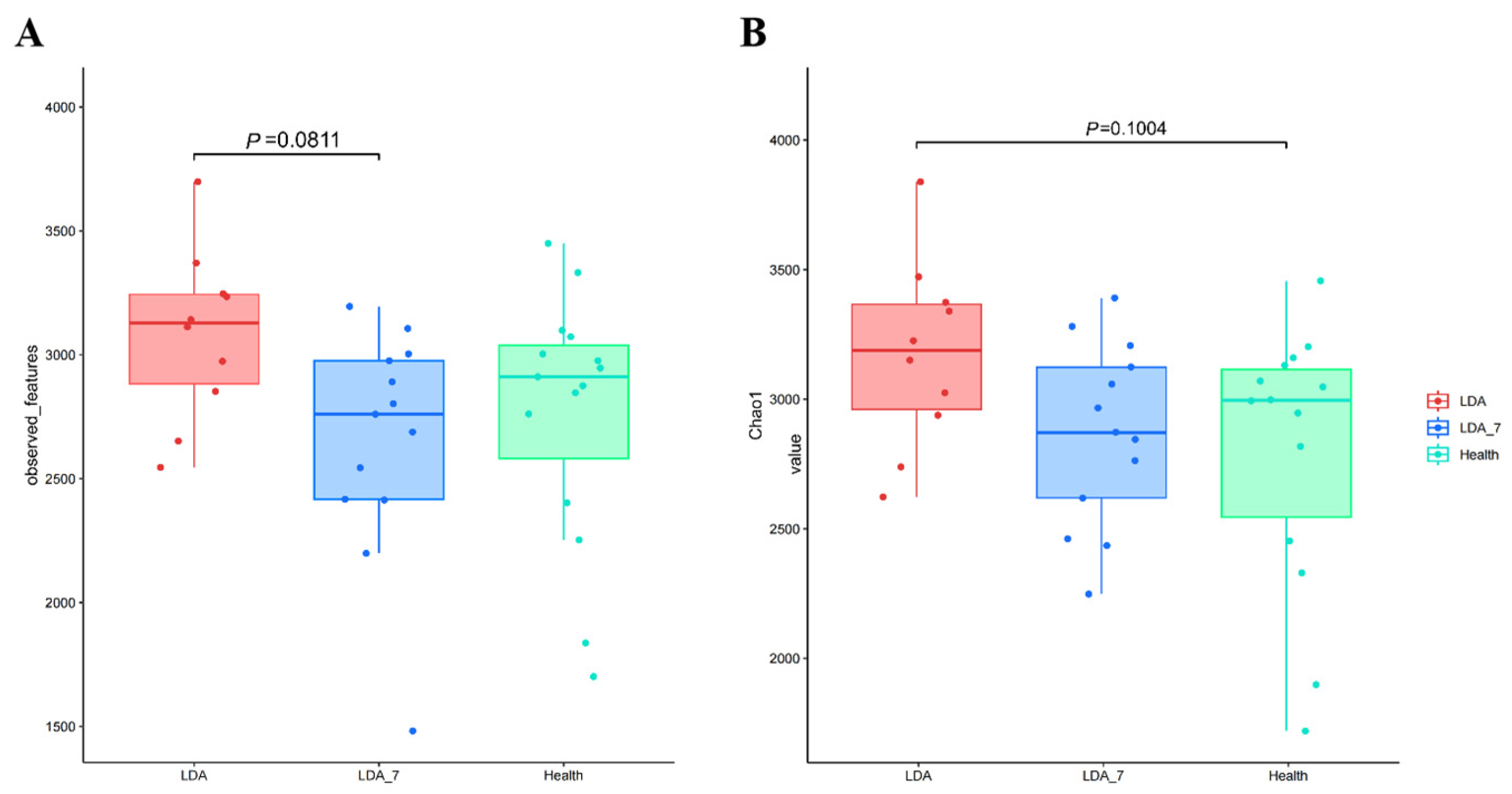

3.1.2. Alpha Diversity Analysis

3.1.3. Beta Diversity Analysis

3.1.4. LEfSe Analysis

3.2. Structural Composition and Differential Analysis of the Bacterial Microbiota

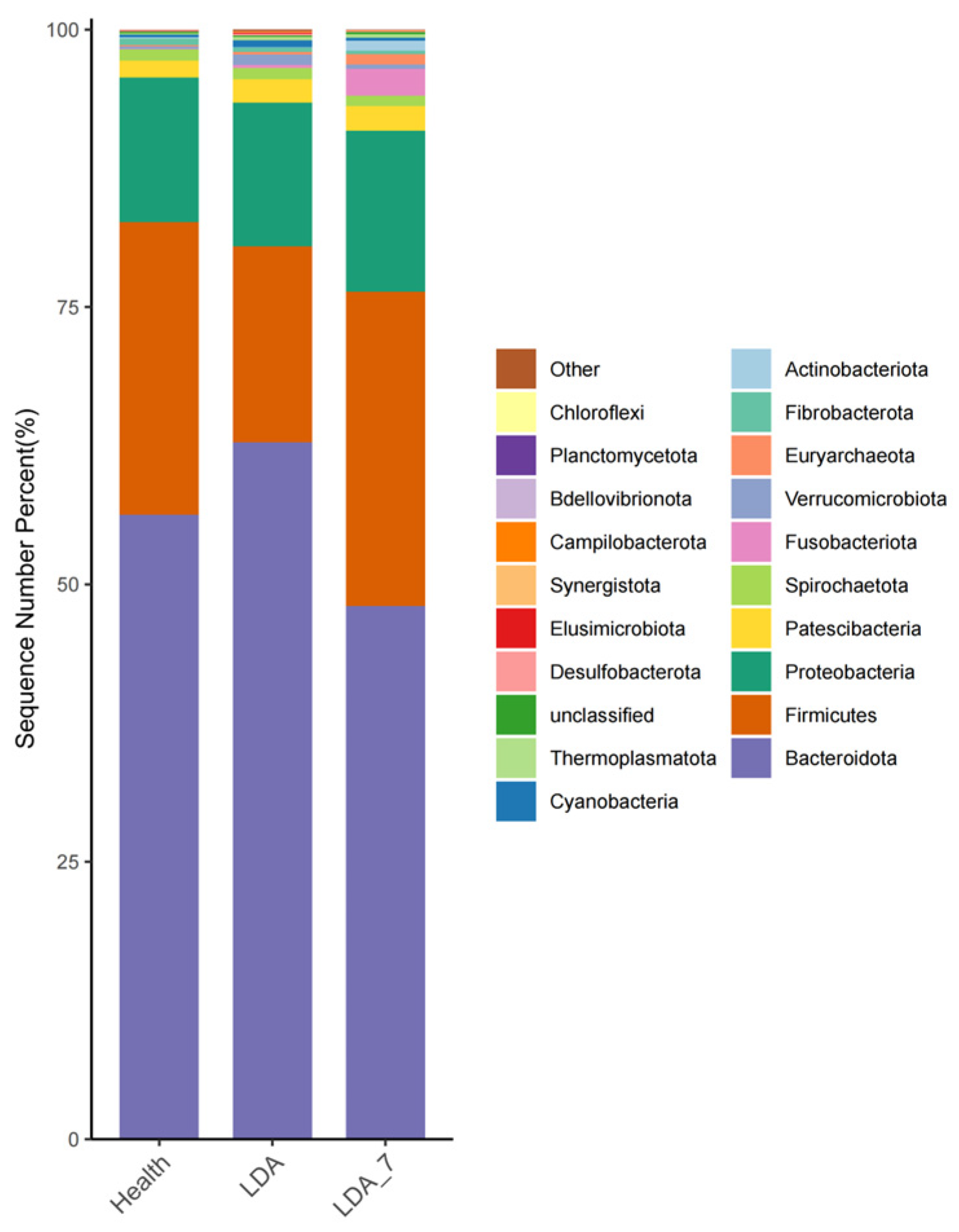

3.2.1. Differences at the Phylum Level

3.2.2. Differences at the Genus Level

3.3. Predictive Analysis of Microbial Function

Analysis of Differences in Tertiary Metabolic Functions

3.4. Correlations Between Genera and Metabolic Pathways

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braun, U.; Nuss, K.; Reif, S.; Hilbe, M.; Gerspach, C. Left and right displaced abomasum and abomasal volvulus: Comparison of clinical, laboratory and ultrasonographic findings in 1982 dairy cows. Acta Vet. Scand 2022, 64, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, V.; Hamann, H.; Scholz, H.; Distl, O. Influences on the occurrence of abomasal displacements in German holstein cows. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2001, 108, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, W.; Howard, J.T.; Paz, H.A.; Hales, K.E.; Wells, J.E.; Kuehn, L.A.; Erickson, G.E.; Spangler, M.L.; Fernando, S.C. Influence of host genetics in shaping the rumen bacterial community in beef cattle. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Winden, S.C.; Kuiper, R. Left displacement of the abomasum in dairy cattle: Recent developments in epidemiological and etiological aspects. Vet. Res. 2003, 34, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plemyashov, K.; Krutikova, A.; Belikova, A.; Kuznetsova, T.; Semenov, B. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) for left displaced abomasum in highly productive Russian holstein cattle. Animals 2024, 14, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Winden, S.C.; Jorritsma, R.; Müller, K.E.; Noordhuizen, J.P. Feed intake, milk yield, and metabolic parameters prior to left displaced abomasum in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Saun, R.J.; Sniffen, C.J. Transition cow nutrition and feeding management for disease prevention. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2014, 30, 689–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschoner, T.; Zablotski, Y.; Feist, M. Retrospective evaluation of method of treatment, laboratory findings, and concurrent diseases in dairy cattle diagnosed with left displacement of the abomasum during time of hospitalization. Animals 2022, 12, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, I.; Ok, M.; Coskun, A. The level of serum ionized calcium, aspartate aminotransferase, insulin, glucose, betahydroxybutyrate concentrations and blood gas parameters in cows with left displacement of abomasum. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2006, 9, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshani, H.; Tun, H.M.; Cardoso, F.C.; Plaizier, J.C.; Khafipour, E.; Loor, J.J. Linking peripartal dynamics of ruminal microbiota to dietary changes and production parameters. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elolimy, A.A.; Liang, Y.; Wilachai, K.; Alharthi, A.S.; Paengkoum, P.; Trevisi, E.; Loor, J.J. Residual feed intake in peripartal dairy cows is associated with differences in milk fat yield, ruminal bacteria, biopolymer hydrolyzing enzymes, and circulating biomarkers of immunometabolism. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 6654–6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, J.R.; Burke, C.R.; Crookenden, M.A.; Heiser, A.; Loor, J.L.; Meier, S.; Mitchell, M.D.; Phyn, C.V.C.; Turner, S.A. Fertility and the transition dairy cow. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2017, 30, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golder, H.M.; Thomson, J.; Rehberger, J.; Smith, A.H.; Block, E.; Lean, I.J. Associations among the genome, rumen metabolome, ruminal bacteria, and milk production in early-lactation holsteins. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 3176–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehner, S.; Zerbin, I.; Doll, K.; Rehage, J.; Distl, O. A genome-wide association study for left-sided displacement of the abomasum using a high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism array. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, M.L.; Cersosimo, L.M.; Wright, A.D.; Kraft, J. Rumen bacterial communities shift across a lactation in holstein, jersey and holstein × jersey dairy cows and correlate to rumen function, bacterial fatty acid composition and production parameters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Barbería, F.J. The Ruminant: Life History and Digestive Physiology of a Symbiotic Animal; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonson, A.J.; Lean, I.J.; Weaver, L.D.; Farver, T.; Webster, G. A body condition scoring chart for holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1989, 72, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.Y.; Huo, W.J.; Zhu, W.Y. Microbiome-metabolome analysis reveals unhealthy alterations in the composition and metabolism of ruminal microbiota with increasing dietary grain in a goat model. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caixeta, L.S.; Herman, J.A.; Johnson, G.W.; McArt, J.A.A. Herd-Level Monitoring and Prevention of Displaced Abomasum in Dairy Cattle. Vet. Clin. Food Anim. Pract. 2018, 34, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trent, A.M. Surgery of the bovine abomasum. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 1990, 6, 399–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulleners, E.P. Prevention and treatment of complications of bovine gastrointestinal surgery. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 1990, 6, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehaus, A.J. Surgical Management of Abomasal Disease. Vet. Clin. Food Anim. Pract. 2016, 32, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schären-Bannert, M.; Bittner-Schwerda, L.; Rachidi, F.; Starke, A. Case report: Complications after using the “blind-stitch” method in a dairy cow with a left displaced abomasum: Treatment, outcome, and economic evaluation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1470190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, K.D.; Harvey, D.; Roy, J.P. Minimally invasive field abomasopexy techniques for correction and fixation of left displacement of the abomasum in dairy cows. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2008, 24, 359–382, viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, J.P.; Harvey, D.; Bélanger, A.M.; Buczinski, S. Comparison of 2-step laparoscopy-guided abomasopexy versus omentopexy via right flank laparotomy for the treatment of dairy cows with left displacement of the abomasum in on-farm settings. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 232, 1700–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis Lage, C.F.; Räisänen, S.E.; Melgar, A.; Nedelkov, K.; Chen, X.J.; Oh, J.; Oh, M.E.; Indugu, N.; Bender, J.S.; Vecchiarelli, B.; et al. Comparison of Two Sampling Techniques for Evaluating Ruminal Fermentation and Microbiota in the Planktonic Phase of Rumen Digesta in Dairy Cows. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 618032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Dada, S.H. High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Jiang, Y.; Balaban, M.; Cantrell, K.; Zhu, Q.; Gonzalez, A.; Morton, J.T.; Nicolaou, G.; Parks, D.P.; Karst, S.M.; et al. Greengenes2 unifies microbial data in a single reference tree. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Van, T.W.; White, R.A.; Eggesbø, M.; Knight, R.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of composition of microbiomes: A novel method for studying microbial composition. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 27663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.W.; Xu, Q.S.; Zhang, R.H.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.M.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.W. Ultrasonographic findings in cows with left displacement of abomasum, before and after reposition surgery. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, E.S.; Jung, S.I.; Park, H.J.; Seo, K.W.; Son, J.H.; Hong, S.; Shim, M.; Kim, H.B.; Song, K.H. Comparison of fecal microbiota between German holstein dairy cows with and without left-sided displacement of the abomasum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 1140–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faniyi, T.O.; Adegbeye, M.J.; Elghandour, M.M.M.Y.; Pilego, A.B.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Olaniyi, T.A.; Adediran, O.; Adewumi, M.K. Role of diverse fermentative factors towards microbial community shift in ruminants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.Y.; Xie, Y.Y.; Zang, X.W.; Zhong, Y.F.; Ma, X.J.; Sun, H.Z.; Liu, J.X. Deciphering functional groups of rumen microbiome and their underlying potentially causal relationships in shaping host traits. Imeta 2024, 3, e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, Z.; Hou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z. High-production dairy cattle exhibit different rumen and fecal bacterial community and rumen metabolite profile than low-production cattle. Microbiologyopen 2019, 8, e00673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, M.P.; Couto, N.; Karunakaran, E.; Biggs, C.A.; Wright, P.C. Deciphering the unique cellulose degradation mechanism of the ruminal bacterium Fibrobacter succinogenes S85. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuti, A.; Brufani, F.; Menculini, G.; Moretti, P.; Tortorella, A. The complex relationship between gut microbiota dysregulation and mood disorders: A narrative review. Curr. Res. Neurobiol. 2022, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Guardia-Hidrogo, V.M.; Paz, H.A. Bacterial community structure in the rumen and hindgut is associated with nitrogen efficiency in holstein cows. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, E.; Algavi, Y.M.; Borenstein, E. The gut microbiome-metabolome dataset collection: A curated resource for integrative meta-analysis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhidary, I.A.; Abdelrahman, M.M.; Elsabagh, M. A comparative study of four rumen buffering agents on productive performance, rumen fermentation and meat quality in growing lambs fed a total mixed ration. Animal 2019, 13, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, G.; Cox, F.; Ganesh, S.; Jonker, A.; Young, W.; Janssen, P.H. Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Hitch, T.C.A.; Chen, Y.; Creevey, C.J.; Guan, L.L. Comparative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses reveal the breed effect on the rumen microbiome and its associations with feed efficiency in beef cattle. Microbiome 2019, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Tian, J.; Tian, P.; Cong, R.; Luo, Y.; Geng, Y.; Tao, S.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, R. Feeding a high concentration diet induces unhealthy alterations in the composition and metabolism of ruminal microbiota and host response in a goat model. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Sun, X.; Yang, B.; Ge, L.; Meng, Z.M.; Cao, X.; Zhang, X.M.; et al. Deciphering functional landscapes of rumen microbiota unveils the role of Prevotella bryantii in milk fat synthesis in goats. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami, E.; Mizrahi, I. Composition and similarity of bovine rumen microbiota across individual animals. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Sun, H.; Wu, X.; Guan, L.L.; Liu, J. Assessment of Rumen Microbiota from a Large Dairy Cattle Cohort Reveals the Pan and Core Bacteriomes Contributing to Varied Phenotypes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00970-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur-Murillo, C.L.; Aguilar-Marín, S.B.; Jovel, J. Prevotella: A key player in ruminal metabolism. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadroňová, M.; Šťovíček, A.; Jochová, K.; Výborná, A.; Tyrolová, Y.; Tichá, D.; Homolka, P.; Joch, M. Combined effects of nitrate and medium-chain fatty acids on methane production, rumen fermentation, and rumen bacterial populations in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.Y.; Sun, H.Z.; Wu, X.H.; Liu, J.X.; Guan, L.L. Multiomics reveals that the rumen microbiome and its metabolome together with the host metabolome contribute to individualized dairy cow performance. Microbiome 2020, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, C.G.; Broderick, G.A. A 100-year review: Protein and amino acid nutrition in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10094–10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, V.A.; Park, S.O. In vivo monitoring of glycerolipid metabolism in animal nutrition biomodel-fed smart-farm eggs. Foods 2024, 13, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Tan, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, J.; Shuai, H.; et al. Metabolic syndrome and cancer risk: A two-sample mendelian randomization study of European ancestry. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emilia, N.; Pia, S.V.; Tiina, H.P.; Antti, N.; Anniina, V.; Anneli, R.; Michael, L.; Natalia, R.S. In vitro protein digestion and carbohydrate colon fermentation of microbial biomass samples from bacterial, filamentous fungus and yeast sources. Food Res. Int. 2024, 182, 114146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Age | Litter Size | Days of Lactation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 2.87 ± 1.13 | 2.00 ± 1.13 | 17.07 ± 3.53 |

| LDA | 3.73 ± 1.67 | 2.20 ± 1.32 | 17.27 ± 4.45 |

| Group1 | Group2 | Pseudo-F | p Value | q-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bray–Curtis | LDA | Health | 3.700 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| LDA | LDA_7 | 1.238 | 0.130 | 0.130 | |

| LDA_7 | Health | 2.398 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Unweighted Unifrac | LDA | Health | 1.583 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| LDA | LDA_7 | 1.127 | 0.090 | 0.090 | |

| LDA_7 | Health | 1.217 | 0.020 | 0.030 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qin, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Y.; Hu, H.; Chu, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, X.; Yao, G.; Wang, C.; et al. Effects of Left-Displaced Abomasum on the Rumen Microbiota of Dairy Cows. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010030

Qin Z, Sun Y, Zhang J, Cui Y, Hu H, Chu Y, Li X, Ma X, Yao G, Wang C, et al. Effects of Left-Displaced Abomasum on the Rumen Microbiota of Dairy Cows. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Zihang, Yawei Sun, Jiaqi Zhang, Yunle Cui, Haiyang Hu, Yuefeng Chu, Xin Li, Xuelian Ma, Gang Yao, Chuanjun Wang, and et al. 2026. "Effects of Left-Displaced Abomasum on the Rumen Microbiota of Dairy Cows" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010030

APA StyleQin, Z., Sun, Y., Zhang, J., Cui, Y., Hu, H., Chu, Y., Li, X., Ma, X., Yao, G., Wang, C., Wang, B., Fu, Q., Zhong, Q., & Li, N. (2026). Effects of Left-Displaced Abomasum on the Rumen Microbiota of Dairy Cows. Microorganisms, 14(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010030