Comparison of Commercial Lateral Flow Immunochromatography with Phenotypic and Genotypic Assays for the Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria at Tanta University Hospitals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Location, and Duration

2.2. Sample Size Justification

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Ethical Consideration

2.5. Samples Collection and Processing

2.6. Phenotypic Detection of Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria

2.7. Detection of Carbapenemase Enzyme Production

- Phenotypic Assay

- II.

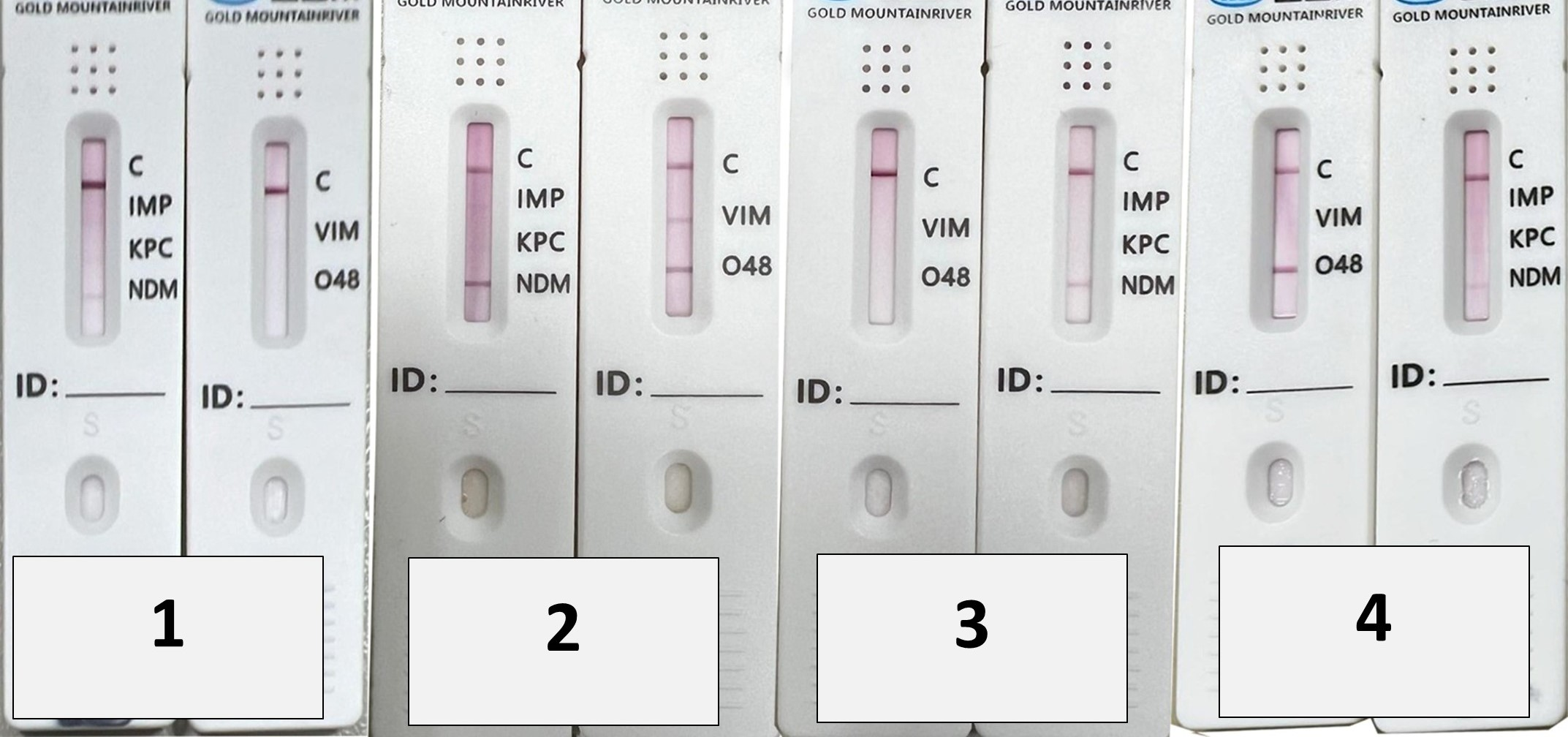

- Immunochromatographic assay (Lateral Flow Immunoassay)

- III.

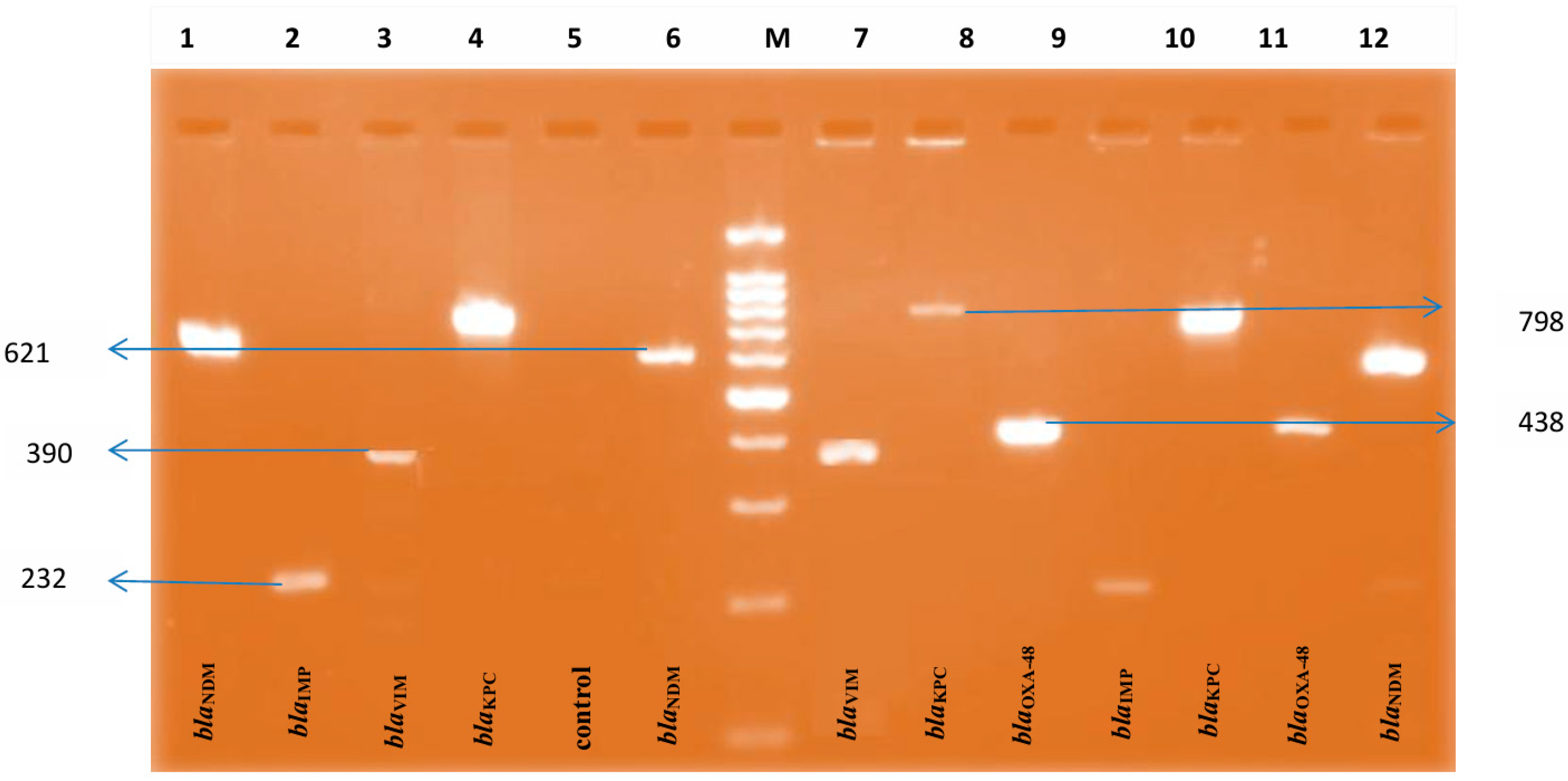

- Genotypic Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Isolates

3.2. Phenotypic Detection of Carbapenemase Enzyme Production

3.3. Lateral Flow Immunoassay and Genotypic Assay in Detection of Carbapenemase Enzyme Production

3.4. Detection of Single or Multiple Carbapenemase-Encoding Genes by Lateral Flow Assay

3.5. Detection of Single or Multiple Carbapenemase-Encoding Genes by PCR

3.6. Lateral Flow Assay in Comparison with PCR

3.7. Phenotypic Methods in Comparison with PCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y.T.; Lin, H.H.; Tseng, K.H.; Lee, T.F.; Huang, Y.T.; Hsueh, P.R. Comparison of ERIC carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae test, BD Phoenix CPO detect panel, and NG-test CARBA 5 for the detection of main carbapenemase types of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2024, 57, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikita, K.; Tajima, M.; Haque, A.; Kato, Y.; Iwata, S.; Suzuki, K.; Hasegawa, N.; Yano, H.; Matsumoto, T. Development of a Simple Method to Detect the Carbapenemase-Producing Genes blaNDM, blaOXA-48-like, blaIMP, blaKPC, and blaVIM Using a LAMP Method with Lateral Flow DNA Chromatography. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defrawy, I.; Salem, D.; Ali, G.; Gamal, D.; El Dabaa, E.; Diab, M.; Alyan, S.A.; Sallam, M.K. Carbapenemase producing Enterobacterales clinical isolates from a tertiary care hospital in Egypt. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain, N.U.; Elton, L.; Sadouki, Z.; McHugh, T.D.; Riaz, S. Exploring New Delhi Metallo Beta Lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli: Genotypic vs. phenotypic insights. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2025, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour El Deen, A.M.; Naga, Y.S.; El Menshawy, A.M.; Roshdy, Y.S. Phenotypic versus molecular assays for detecting carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales from urinary tract infections. Microbes Infect. Dis. 2024, 5, 1506–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, N.A.; Elsayed, L.A.; ElMasry, S.A. Diagnostic Efficacy of the Carba NP Strip Test for Carbapenemase Detection. Afro-Egypt. J. Infect. Endem. Dis. 2023, 13, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, P.; Berger, A.-S.; Evrard, S.; Huang, T.-D. Comparison of two multiplex immunochromatographic assays for the rapid detection of major carbapenemases in Enterobacterales. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 1491–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuffari, S.; Aiezza, N.; Antonelli, A.; Giani, T.; Rossolini, G.M. Evaluation of three commercial lateral flow immunoassays for the detection of KPC, VIM, NDM, IMP and OXA-48-like carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 2724–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrahem, A.A.; El-Mashad, N.; Elshaer, M.; Ramadan, H.; Damiani, G.; Bahgat, M.; Mercuri, S.R.; Elemshaty, W. Carbapenem Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Hospital-Based Study in Egypt. Medicina 2023, 59, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI M100; Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2022.

- Freschi, C.R.; Silva Carvalho, L.F.; Oliveira, C.J. Comparison of DNA-extraction methods and selective enrichment broths on the detection of Salmonella typhimurium in swine feces by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Braz. J. Microbiol. 2005, 36, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Cuvillier, V.; Nordmann, P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, J.W.; Chibabhai, V. Evaluation of the RESIST-4 O.K.N.V immunochromatographic lateral flow assay for the rapid detection of OXA-48, KPC, NDM and VIM carbapenemases from cultured isolates. Access Microbiol. 2019, 1, e000031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Guo, Y.; Peng, M.; Shi, Q.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yin, D.; Hu, F. Evaluation of the Immunochromatographic NG-Test Carba 5, RESIST-5 O.O.K.N.V., and IMP K-SeT for Rapid Detection of KPC-, NDM-, IMP-, VIM-type, and OXA-48-like Carbapenemase Among Enterobacterales. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 609856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Sotelo, B.J.; López-Jácome, L.E.; Colín-Castro, C.A.; Hernández-Durán, M.; Martínez-Zavaleta, M.G.; Rivera-Buendía, F.; Velázquez-Acosta, C.; Rodríguez-Zulueta, A.P.; Morfín-Otero, M.D.R.; Franco-Cendejas, R. Comparison of lateral flow immunochromatography and phenotypic assays to PCR for the detection of carbapenemase-producing gram-negative bacteria, a multicenter experience in Mexico. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, H.; Xu, M.; Li, D.; Ran, X.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Z. Comparing the broth enrichment-multiplex lateral flow immunochromatographic assay with real time quantitative PCR for the rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing organisms in rectal swabs. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, S.; Shafiee, F.; Hakamifard, A.; Fazeli, H.; Soltani, R. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative nosocomial bacteria at Al Zahra hospital, Isfahan, Iran. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2021, 13, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yin, Y.; Chen, H.; Jin, L.; Gu, B.; Xie, L.; Yang, C.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; et al. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections: Report from the China CRE Network. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01882-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasko, M.J.; Gill, C.M.; Asempa, T.E.; Nicolau, D.P. EDTA-modified carbapenem inactivation method (eCIM) for detecting IMP Metallo-β-lactamase–producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An assessment of increasing EDTA concentrations. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther-Rasmussen, J.; Høiby, N. OXA-type carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, T.; Mir, A.A.; Roohi, S.; Fomda, B.; Wani, S.R.; Ahmed, T.; Yousuf, S. Detection of carbapenemase production in Enterobacterales by mCIM and eCIM: A tertiary care hospital study. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2025, 17, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamsi, S.K.; Moorthy, R.S.; Hemiliamma, M.N.; Chandra Reddy, R.B.; Chanderakant, D.J.; Sirikonda, S. Phenotypic and genotypic detection of carbapenemase production among Gram-negative bacteria isolated from hospital-acquired infections. Saudi Med. J. 2022, 43, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwakar, J.; Verma, R.K.; Singh, D.P.; Singh, A.; Kumari, S. Phenotypic detection of carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative bacilli from various clinical specimens of a tertiary care hospital in Western Uttar Pradesh. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2017, 5, 3511–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.K.; Mohite, S.T.; Shinde, R.V.; Patil, S.R.; Karande, G.S. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Prevalence and bacteriological profile in a tertiary teaching hospital from rural western India. Indian J. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 5, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Moodley, A.; Perovic, O. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing in predicting the presence of carbapenemase genes in Enterobacteriaceae in South Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.A.; Elhag, W.I. Prevalence of metallo-β-lactamase acquired genes among carbapenems susceptible and resistant Gram-negative clinical isolates using multiplex PCR, Khartoum hospitals, Khartoum Sudan. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, S.; Basu, S.; Simner, P.J.; Kambli, P.; Shetty, A.; Rodrigues, C. Evaluation of the rapid lateral flow assay (LFA) for detection of five major carbapenemase enzyme families in genotypically characterised bacterial isolates. Indian J. Med. Res. 2025, 161, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.; Göttig, S.; Hamprecht, A.G. Multiplex immunochromatographic detection of OXA-48, KPC, and NDM carbapenemases: Impact of inoculum, antibiotics, and agar. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00050-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Park, M.J.; Jeong, S.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, N.; Hong, J.S.; Jeong, S.H. Rapid identification of OXA-48-like, KPC, NDM, and VIM carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae from culture: Evaluation of the RESIST-4 O.K.N.V. multiplex lateral flow assay. Ann. Lab. Med. 2020, 40, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar-Duman, M.; Çilli, F.; Tekintaş, Y.; Polat, F.; Hoşgör-Limoncu, M. Carbapenemase investigation with rapid phenotypic test (RESIST-4 O.K.N.V) and comparison with PCR in carbapenem-resistant enterobacterales strains. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2022, 14, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kon, H.; Abramov, S.; Frenk, S.; Schwartz, D.; Shalom, O.; Adler, A.; Carmeli, Y.; Lellouche, J. Multiplex lateral flow immunochromatographic assay is an effective method to detect carbapenemases without risk of OXA-48-like cross reactivity. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Kang, D.; Kim, D. Performance evaluation of the newly developed in vitro rapid diagnostic test for detecting OXA-48-Like, KPC-, NDM-, VIM- and IMP-type carbapenemases: The RESIST-5 O.K.N.V.I. multiplex lateral flow assay. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, S.; Ihashi, Y.; Yoshino, Y.; Ono, Y. Evaluation of an immunological assay for the identification of multiple carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria. Pathology 2022, 54, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakonjac, B.; Djurić, M.; Djurić-Petković, D.; Dabić, J.; Simonović, M.; Milić, M.; Arsović, A. Evaluation of the NG-Test CARBA 5 for Rapid Detection of Carbapenemases in Clinical Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Qin, M.; Zhao, C.; Yi, S.; Ye, M.; Liao, K.; Deng, J.; Chen, Y. Evaluating the Performance of Two Rapid Immunochromatographic Techniques for Detecting Carbapenemase in Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales Clinical Isolates. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.M.; Wang, S.; Chiu, H.C.; Kao, C.Y.; Wen, L.L. Combination of modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and EDTA-CIM (eCIM) for phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Mi, P.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Luo, K.; Liu, S.; Han, S. The optimized carbapenem inactivation method for objective and accurate detection of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1185450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organisms | mCIM | eCIM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative N = 13 (26%) | Positive N = 37 (74%) | Negative N = 29 (58%) | Positive N = 21 (42%) | ||

| Klebsiella pneumonia (n = 15) | n | 4 | 11 | 9 | 6 |

| % | 30.8% | 29.7% | 31% | 28.6 | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 14) | n | 4 | 10 | 7 | 7 |

| % | 30.8% | 27% | 24.1% | 33.3% | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 11) | n | 3 | 8 | 7 | 4 |

| % | 23.1% | 21.6% | 24.1% | 19% | |

| Escherichia coli (n = 5) | n | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| % | 7.7% | 10.8 | 13.8% | 4.8% | |

| Enterobacter cloacae (n = 3) | n | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| % | 7.7% | 5.4% | 3.4% | 9.5% | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 2) | n | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| % | 0% | 5.4% | 3.4% | 4.8% | |

| Total (n = 50) | Klebsiella pneumonia (n = 15) | Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 14) | Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 2) | Escherichia coli (n = 5) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 11) | Enterobacter coloaca (n = 3) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbapenemase genes by LFIA | ||||||||

| blaKPC | 19 (38%) | 9 (60%) | 5 (35.7%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0.203 |

| blaNDM | 27 (54%) | 7 (46.7%) | 10 (71.4%) | 1 (50%) | 2 (40%) | 5 (45.5%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0.714 |

| blaIMP | 14 (28%) | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (35.7%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0.696 |

| blaVIM | 24 (48%) | 8 (53.3%) | 6 (42.9%) | 1 (50%) | 3 (60%) | 3 (27.3%) | 3 (100%) | 0.351 |

| blaOXA-48 | 18 (44%) | 8 (53.3%) | 5 (35.7%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0.139 * |

| Carbapenemase genes by PCR | ||||||||

| blaKPC | 17 (34%) | 6 (40%) | 5 (35.7%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (20%) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0.970 |

| blaNDM | 23 (46%) | 7 (46.7%) | 9 (64.3%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (20%) | 3 (27.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0.380 |

| blaIMP | 12 (24%) | 3 (20%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0.707 |

| blaVIM | 22 (44%) | 7 (46.7%) | 7 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 3 (60%) | 1 (9.1%) | 3 (100%) | 0.042 * |

| blaOXA-48 | 15 (30%) | 8 (53.3%) | 3 (21.4%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0.016 * |

| Carbapenemase Genes by LFA (N = 50) | Klebsiella pneumonia (N = 15) | Acinetobacter baumannii (N = 14) | Klebsiella oxytoca (N = 2) | Escherichia coli (N = 5) | Pseudomonas aeuroginosa (N = 11) | Enterobacter coloaca (N = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative N = 9 (18%) | ||||||

| 1 (6.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (36.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Single gene N = 11 (22%) | ||||||

| blaIMP (N= 0) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC (N = 0) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaNDM (N= 3) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaOXA-48 (N= 2) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaVIM (N = 6) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Double genes N = 12 (24%) | ||||||

| blaIMP + blaNDM (N = 5) | 0 (0%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC + blaNDM (N = 3) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC + blaOXA-48 (N = 1) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC + blaVIM (N = 1) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaNDM + blaOXA-48 (N = 1) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaNDM + blaVIM (N = 1) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Triple genes N = 8 (16%) | ||||||

| blaIMP + blaKPC + blaOXA-48 (N= 1) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC + blaNDM + blaOXA-48 (N= 1) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC + blaNDM + blaVIM (N= 2) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC + blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N= 2) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaNDM + blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N= 2) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Quadruple genes N = 7 (14%) | ||||||

| blaIMP+ blaKPC +blaNDM + blaVIM (N= 2) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaIMP+ blaKPC +blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 1) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaIMP+ blaNDM +blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 2) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| blaKPC+ blaNDM +blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 2) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| All five genes N = 3 (6%) | ||||||

| blaIMP+ blaKPC +blaNDM+ blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 3) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Carbapenemase Genes by PCR N = 50 | Klebsiella pneumonia (n = 15) | Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 14) | Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 2) | Escherichia coli (n = 5) | Pseudomonas aeuroginosa (n = 11) | Enterobacter coloaca (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative N = 9 (18%) | ||||||

| 1 (6.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (36.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Single gene N = 17 (34%) | ||||||

| blaIMP (N = 2) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC (N= 3) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaNDM (N= 2) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaOXA-48 (N= 4) | 4 (53.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaVIM (N= 6) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Double genes N = 9 (18%) | ||||||

| blaIMP+blaKPC (N = 1) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaIMP+blaNDM (N = 2) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC+ blaNDM (N = 4) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaNDM+ blaOXA-48 (N = 1) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaNDM+ blaVIM (N = 1) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Triple genes N = 8 (16%) | ||||||

| blaIMP+ blaNDM + blaVIM (N = 2) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC+ blaNDM + blaVIM (N = 1) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaKPC+ blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 2) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaNDM+ blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 3) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Quadruple genes N = 5 (10%) | ||||||

| blaIMP+blaKPC +blaNDM + blaVIM (N = 2) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| blaIMP+blaNDM +blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 1) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| blaKPC+blaNDM +blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 2) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| All five genes N = 2 (4%) | ||||||

| blaIMP+blaKPC +blaNDM+ blaOXA-48 + blaVIM (N = 3) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| PCR | Lateral Flow Results | Kappa Value | p-Value | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||||||||

| blaIMP | Negative (n = 38) Positive (n = 12) | 35 (92.1%) 1 (8.3%) | 3 (7.9%) 11 (91.7%) | 0.793 | <0.001 | 91.7% | 92.1% | 78.6% | 97.2% | 92% |

| blaKPC | Negative (n = 33) Positive (n = 17) | 30 (90.9%) 1 (5.9%) | 3 (9.1%) 16 (94.1%) | 0.827 | <0.001 | 94.1% | 90.9% | 84.2% | 96.8% | 92% |

| blaNDM | Negative (n = 27) Positive (n = 23) | 23 (85.2%) 0 (0%) | 4 (14.8%) 23 (100%) | 0.841 | <0.001 | 100% | 85.2% | 85.2% | 100% | 92% |

| blaOXA-48 | Negative (n = 35) Positive (n = 15) | 32 (91.4%) 0 (0%) | 3 (8.6%) 15 (100%) | 0.865 | <0.001 | 100% | 91.4% | 83.3% | 91.4% | 94% |

| blaVIM | Negative (n = 28) Positive (n = 22) | 25 (89.3%) 1 (4.5%) | 3 (10.7%) 21 (95.5%) | 0.839 | <0.001 | 95.5% | 89.3% | 87.5% | 96.2% | 92% |

| PCR Genes | mCIM | Kappa Value | p-Value | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative N = 13 | Positive N = 37 | ||||||||

| Negative (n = 9) Positive (n = 41) | 7 (53.8%) 6 (46.2%) | 2 (5.4%) 35 (94.6%) | 0.538 | <0.001 | 94.6% | 53.8%% | 94.6% | 53.8% | 84% |

| eCIM | |||||||||

| Negative (n = 9) Positive (n = 41) | 9 (31%) 20 (69%) | 0 (0%) 21 (100%) | 0.274 | 0.006 | 100% | 31% | 100% | 31% | 60% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Taha, M.S.; Gabr, B.M.; Elaziz, W.A.; Elgohary, A.M.; Kasem, B.S.; Elkolaly, R.M.; Elatrozy, H.I.S.; Emam, M.N.; Essawy, A.S.; Eldin, H.E.M.S.; et al. Comparison of Commercial Lateral Flow Immunochromatography with Phenotypic and Genotypic Assays for the Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria at Tanta University Hospitals. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010031

Taha MS, Gabr BM, Elaziz WA, Elgohary AM, Kasem BS, Elkolaly RM, Elatrozy HIS, Emam MN, Essawy AS, Eldin HEMS, et al. Comparison of Commercial Lateral Flow Immunochromatography with Phenotypic and Genotypic Assays for the Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria at Tanta University Hospitals. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaha, Marwa S., Basant Mostafa Gabr, Wafaa Abd Elaziz, Ahmed Mostafa Elgohary, Bsant S. Kasem, Reham M. Elkolaly, Hytham I. S. Elatrozy, Marwa N. Emam, Asmaa S. Essawy, Heba E. M. Sharaf Eldin, and et al. 2026. "Comparison of Commercial Lateral Flow Immunochromatography with Phenotypic and Genotypic Assays for the Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria at Tanta University Hospitals" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010031

APA StyleTaha, M. S., Gabr, B. M., Elaziz, W. A., Elgohary, A. M., Kasem, B. S., Elkolaly, R. M., Elatrozy, H. I. S., Emam, M. N., Essawy, A. S., Eldin, H. E. M. S., Mohamed, R. A., Elkadeem, M. Z., Abdelbaky, S., & Gadallah, M. A. E.-A. (2026). Comparison of Commercial Lateral Flow Immunochromatography with Phenotypic and Genotypic Assays for the Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria at Tanta University Hospitals. Microorganisms, 14(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010031