Gastrointestinal Journey of Human Milk Oligosaccharides: From Breastfeeding Origins to Functional Roles in Adults

Abstract

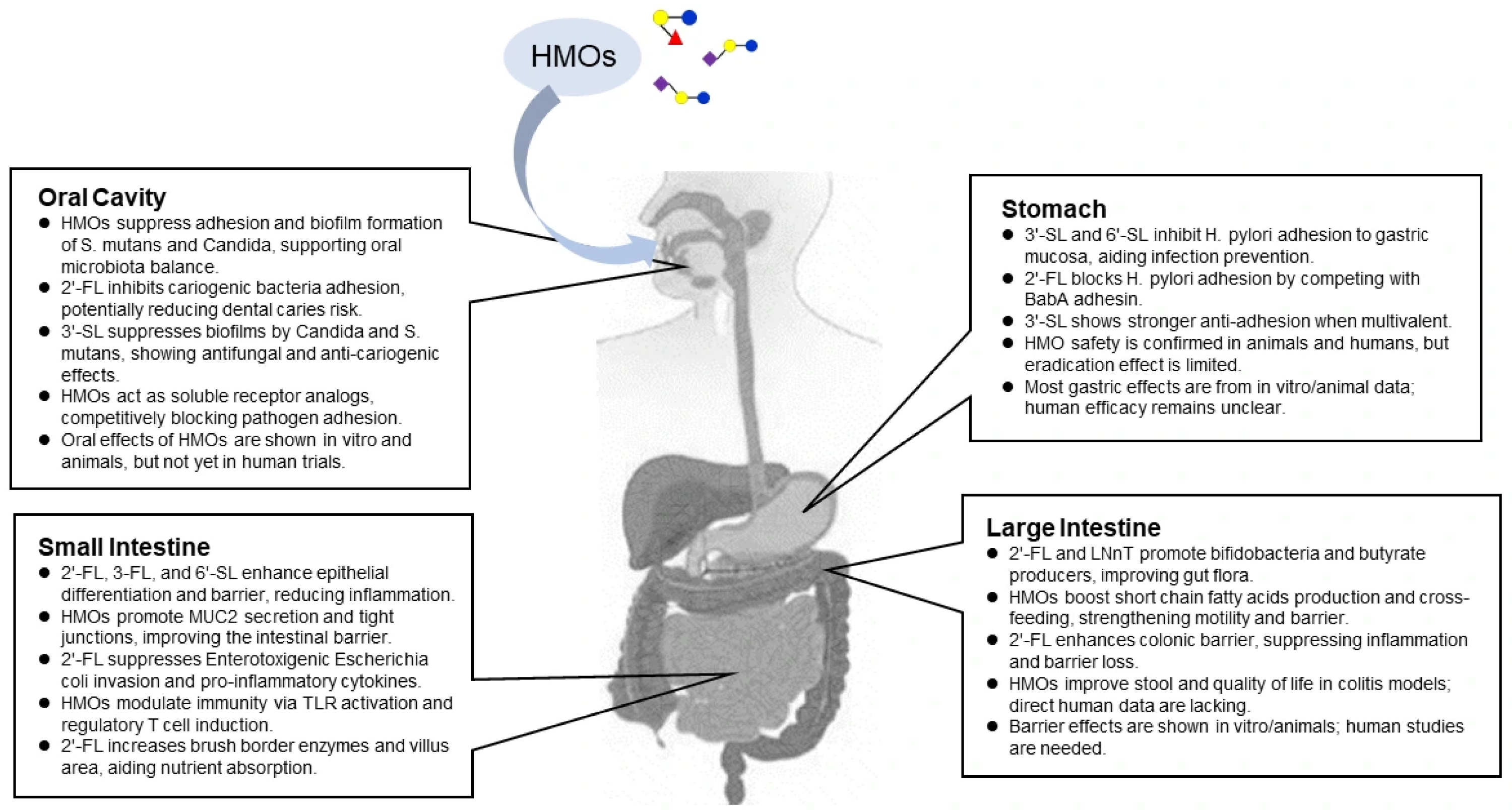

1. Introduction

2. Oral Section

Contribution of HMOs to Oral Health

3. Stomach Section

Preventive Effects of HMOs on Helicobacter pylori Infection

4. Small Intestine Section

4.1. Barrier-Enhancing Effects of HMOs in the Small Intestine

4.2. Immunomodulatory Effects of HMOs

4.3. Effects of HMOs on Improving Nutrient Absorption

5. Large Intestine Section

5.1. Prebiotic Effects of HMOs

5.2. Gut-Modulatory Effects of HMOs

5.3. Colonic Barrier-Enhancing Effects of HMOs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

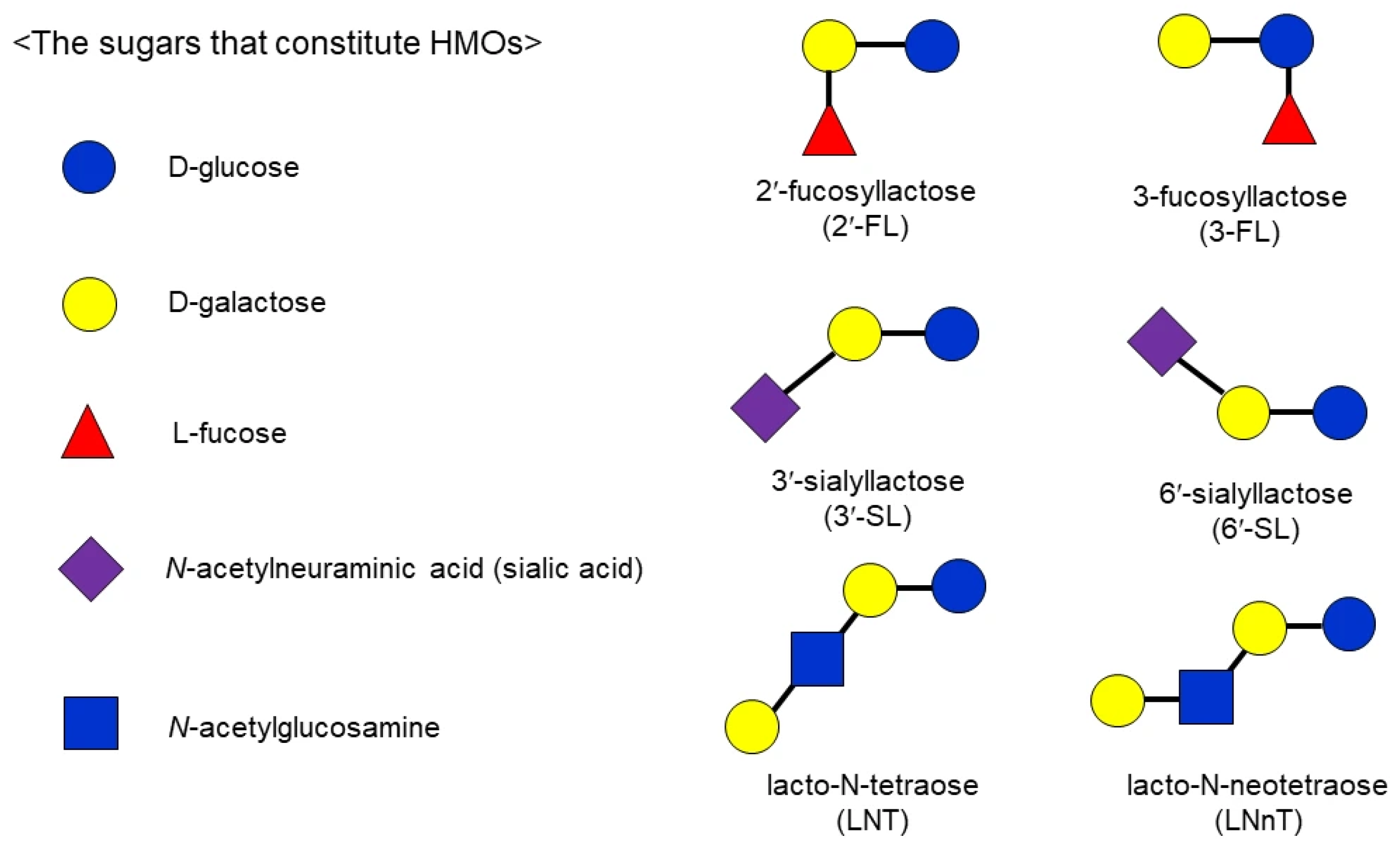

Abbreviations

| 2′-FL | 2′-Fucosyllactose |

| 3-FL | 3-Fucosyllactose |

| HMO(s) | Human Milk Oligosaccharide(s) |

| IBS | Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

| LNnT | Lacto-N-neotetraose |

| LNT | Lacto-N-tetraose |

| NEC | Necrotizing Enterocolitis |

| SCFA(s) | Short-Chain Fatty Acid(s) |

| SHIME | Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem |

| 3′-SL | 3′-Sialyllactose |

| 6′-SL | 6′-Sialyllactose |

References

- Dinleyici, M.; Barbieur, J.; Dinleyici, E.C.; Vandenplas, Y. Functional effects of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs). Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2186115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plows, J.F.; Berger, P.K.; Jones, R.B.; Alderete, T.L.; Yonemitsu, C.; Najera, J.A.; Khwajazada, S.; Bode, L.; Goran, M.I. Longitudinal changes in human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) over the course of 24 months of lactation. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiciński, M.; Sawicka, E.; Gębalski, J.; Kubiak, K.; Malinowski, B. Human milk oligosaccharides: Health benefits, potential applications in infant formulas, and pharmacology. Nutrients 2020, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, L. Human milk oligosaccharides: Every baby needs a sugar mama. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 1147–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, L. The functional biology of human milk oligosaccharides. Early Hum. Dev. 2015, 91, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurama, H.; Kiyohara, M.; Wada, J.; Honda, Y.; Yamaguchi, M.; Fukiya, S.; Yokota, A.; Ashida, H.; Kumagai, H.; Kitaoka, M.; et al. Lacto-N-biosidase encoded by a novel gene of Bifidobacterium longum subspecies longum shows unique substrate specificity and requires a designated chaperone for its active expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 25194–25206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.T.; Chen, C.; Newburg, D.S. Utilization of major fucosylated and sialylated human milk oligosaccharides by isolated human gut microbes. Glycobiology 2013, 23, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongaram, T.; Hoeflinger, J.L.; Chow, J.; Miller, M.J. Human milk oligosaccharide consumption by probiotic and human-associated bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 7825–7833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salli, K.; Hirvonen, J.; Siitonen, J.; Ahonen, I.; Anglenius, H.; Maukonen, J. Selective utilization of the human milk oligosaccharides 2′-fucosyllactose, 3-fucosyllactose, and difucosyllactose by various probiotic and pathogenic bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 69, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Cervantes, L.E.; Ramos, P.; Chavez-Munguia, B.; Newburg, D.S. Campylobacter jejuni binds intestinal H (O) antigen (Fucα1,2Galβ1,4GlcNAc), and fucosyloligosaccharides of human milk inhibit its binding and infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14112–14120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, F.; Sharma, A.K.; Gurung, M.; Casero, D.; Matazel, K.; Bode, L.; Simecka, C.; Elolimy, A.A.; Tripp, P.; Randolph, C.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharides impact cellular and inflammatory gene expression and immune response. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.K.; Das, J.C.; Maruf-UL-Quader, M.; Chowdhury, Z.; Haque, S.; Chowdhury, M.J.B.A.; Das, A.K.; Chowdhury, D. Human milk oligosaccharides and development of gut microbiota with immune system in newborn infants. Am. J. Pediatr. 2024, 9, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Holscher, H.D.; Davis, S.R.; Tappenden, K.A. Human milk oligosaccharides influence maturation of human intestinal Caco-2Bbe and HT-29 cell lines. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natividad, J.M.; Rytz, A.; Keddani, S.; Bergonzelli, G.; Garcia-Rodenas, C.L. Blends of human milk oligosaccharides confer intestinal epithelial barrier protection in vitro. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppa, G.V.; Zampini, L.; Galeazzi, T.; Facinelli, B.; Ferrante, L.; Capretti, R.; Orazio, G. Human milk oligosaccharides inhibit the adhesion to Caco-2 cells of diarrheal pathogens: Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, and Salmonella fyris. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 59, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Berger, B.; Carnielli, V.P.; Ksiazyk, J.; Lagström, H.; Sanchez Luna, M.; Migacheva, N.; Mosselmans, J.-M.; Picaud, J.-C.; Possner, M.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharides: 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) in infant formula. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puccio, G.; Alliet, P.; Cajozzo, C.; Janssens, E.; Corsello, G.; Sprenger, N.; Wernimont, S.; Egli, D.; Gosoniu, L.; Steenhout, P. Effects of infant formula with human milk oligosaccharides on growth and morbidity: A randomized multicenter trial. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goehring, K.C.; Marriage, B.J.; Oliver, J.S.; Wilder, J.A.; Barrett, E.G.; Buck, R.H. Similar to those who are breastfed, infants fed a formula containing 2′-fucosyllactose have lower inflammatory cytokines in a randomized controlled trial. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2559–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marriage, B.J.; Buck, R.H.; Goehring, K.C.; Oliver, J.S.; Williams, J.A. Infants fed a lower calorie formula with 2′-FL show growth and 2′-FL uptake like breast-fed infants. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 61, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, P.K.; Ong, M.L.; Bode, L.; Belfort, M.B. Human milk oligosaccharides and infant neurodevelopment: A narrative review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; McMath, A.L.; Donovan, S.M. Review on the impact of milk oligosaccharides on the brain and neurocognitive development in early life. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wan, L.; Li, W.; Ni, D.; Zhang, W.; Yan, X.; Mu, W. Recent advances on 2′-fucosyllactose: Physiological properties, applications, and production approaches. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.; Larsen, D.M.; Jers, C.; Almeida, J.R.; Willer, M.; Li, H.; Kirpekar, F.; Kjærulff, L.; Gotfredsen, C.H.; Nordvang, R.T.; et al. Biocatalytic production of 3′-sialyllactose by use of a modified sialidase with superior trans-sialidase activity. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, M.; Hu, M.; Gao, W.; Miao, M.; Zhang, T. Engineering Escherichia coli for the efficient biosynthesis of 6′-sialyllactose. Food Biosci. 2023, 55, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S. Regulatory aspects of human milk oligosaccharides. Nestle Nutr. Inst. Workshop Ser. 2017, 88, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA); Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL) produced by a derivative strain (Escherichia coli SGR5) of E. coli W (ATCC 9637) as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e08333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA); Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of 3′-sialyllactose (3′-SL) sodium salt as a novel food (NF) pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e08224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA); Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of 6′-sialyllactose (6′-SL) sodium salt produced by a derivative strain (Escherichia coli NEO6) of E. coli W (ATCC 9637) as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e08025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassai, S.; de Vos, P. Gastrointestinal barrier function, immunity, and neurocognition: The role of human milk oligosaccharide (HMO) supplementation in infant formula. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.M.; Demis, D.; Perelman, D.; Onge, M.S.; Petlura, C.; Cunanan, K.; Mathi, K.; Maecker, H.T.; Chow, J.M.; Robinson, J.L.; et al. A human milk oligosaccharide alters the microbiome, circulating hormones, and metabolites in a randomized controlled trial of older adults. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza-Díaz, J.; Fontana, L.; Gil, A. Human milk oligosaccharides and immune system development. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.J.; Yeung, C.Y. Recent advance in infant nutrition: Human milk oligosaccharides. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2021, 62, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lordan, C.; Roche, A.K.; Delsing, D.; Nauta, A.; Groeneveld, A.; MacSharry, J.; Cotter, P.D.; van Sinderen, D. Linking human milk oligosaccharide metabolism and early life gut microbiota: Bifidobacteria and beyond. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2024, 88, e00094-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salli, K.; Söderling, E.; Hirvonen, J.; Gürsoy, U.; Ouwehand, A.C. Influence of 2′-fucosyllactose and galacto-oligosaccharides on the growth and adhesion of Streptococcus mutans. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, J.B.; Santiago, M.B.; Silva, C.B.; Geraldo-Martins, V.R.; Nogueira, R.D. Development of Streptococcus mutans biofilm in the presence of human colostrum and 3′-sialyllactose. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassart, D.; Woltz, A.; Golliard, M.; Neeser, J.R. In vitro inhibition of adhesion of Candida albicans clinical isolates to human buccal epithelial cells by Fucα1-2Galβ-bearing complex carbohydrates. Infect. Immun. 1991, 59, 1605–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.B.; Santiago, M.B.; Oliveira, P.H.M.D.; Geraldo-Martins, V.R.; Nogueira, R.D. Effects of 3′-sialyllactose, saliva, and colostrum on Candida albicans biofilms. Einstein 2025, 23, eAO0663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.T.; Nanthakumar, N.N.; Newburg, D.S. The human milk oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose quenches Campylobacter jejuni-induced inflammation in human epithelial cells HEp-2 and HT-29 and in mouse intestinal mucosa. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1980–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Nair, M.R.; Rai, K.; Shetty, V.; Anees, M.T.M.; Shetty, A.K.; D’souza, N. A novel sugar-free probiotic oral rinse influences oral Candida albicans in children with Down syndrome post complete oral rehabilitation: A pilot randomized clinical trial with 6-month follow-up. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turska-Szybka, A.; Olczak-Kowalczyk, D.; Twetman, S. Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics against oral Candida in children: A review of clinical trials. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, N.; Okamoto, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Matsumura, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamakido, M.; Taniyama, K.; Sasaki, N.; Schlemper, R.J. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani, M.; Pakzad, R.; Haddadi, M.H.; Akrami, S.; Asadi, A.; Kazemian, H.; Moradi, M.; Kaviar, V.H.; Zomorodi, A.R.; Khoshnood, S.; et al. The global prevalence of gastric cancer in Helicobacter pylori-infected individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.G.; Evans, D.J., Jr.; Moulds, J.J.; Graham, D.Y. N-acetylneuraminyllactose-binding fibrillar hemagglutinin of Campylobacter pylori: A putative colonization factor antigen. Infect. Immun. 1988, 56, 2896–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.M.; Goode, P.L.; Mobasseri, A.; Zopf, D. Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori binding to gastrointestinal epithelial cells by sialic acid-containing oligosaccharides. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysore, J.V.; Wigginton, T.; Simon, P.M.; Zopf, D.; Heman-Ackah, L.M.; Dubois, A. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in rhesus monkeys using a novel antiadhesion compound. Gastroenterology 1999, 117, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, P.; Nilsson, J.; Ångström, J.; Miller-Podraza, H. Interaction of Helicobacter pylori with sialylated carbohydrates: The dependence on different parts of the binding trisaccharide Neu5Acα3Galβ4GlcNAc. Glycobiology 2005, 15, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walz, A.; Odenbreit, S.; Mahdavi, J.; Borén, T.; Ruhl, S. Identification and characterization of binding properties of Helicobacter pylori by glycoconjugate arrays. Glycobiology 2005, 15, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.; Rossez, Y.; Robbe-Masselot, C.; Maes, E.; Gomes, J.; Shevtsova, A.; Bugaytsova, J.; Borén, T.; Reis, C.A. Muc5ac gastric mucin glycosylation is shaped by FUT2 activity and functionally impacts Helicobacter pylori binding. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.T.; Zhao, Y.F.; Lian, Z.X.; Fan, B.L.; Zhao, Z.H.; Yu, S.Y.; Dai, Y.P.; Wang, L.L.; Niu, H.L.; Li, N.; et al. Effects of fucosylated milk of goat and mouse on Helicobacter pylori binding to Lewis b antigen. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 2063–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, F.; Cucino, C.; Anderloni, A.; Grandinetti, G.; Porro, G.B. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection using a novel antiadhesion compound (3′-sialyllactose sodium salt). A double blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Helicobacter 2003, 8, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holscher, H.D.; Bode, L.; Tappenden, K.A. Human milk oligosaccharides influence intestinal epithelial cell maturation in vitro. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Elderman, M.; Cheng, L.; de Haan, B.J.; Nauta, A.; de Vos, P. Modulation of intestinal epithelial glycocalyx development by human milk oligosaccharides and non-digestible carbohydrates. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1900303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Kong, C.; Walvoort, M.T.; Faas, M.M.; de Vos, P. Human milk oligosaccharides differently modulate goblet cells under homeostatic, proinflammatory conditions and ER stress. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1900976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.Y.; Li, B.; Koike, Y.; Määttänen, P.; Miyake, H.; Cadete, M.; Johnson-Henry, K.C.; Botts, S.R.; Lee, C.; Abrahamsson, T.R.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharides increase mucin expression in experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1800658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niño, D.F.; Sodhi, C.P.; Hackam, D.J. Necrotizing enterocolitis: New insights into pathogenesis and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.N.; Jiang, P.; Jacobsen, S.; Sangild, P.T.; Bendixen, E.; Chatterton, D.E. Protective effects of transforming growth factor β2 in intestinal epithelial cells by regulation of proteins associated with stress and endotoxin responses. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, C.P.; Wipf, P.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Fulton, W.B.; Kovler, M.; Niño, D.F.; Zhou, Q.; Banfield, E.; Werts, A.D.; Ladd, M.R.; et al. The human milk oligosaccharides 2′-fucosyllactose and 6′-sialyllactose protect against the development of necrotizing enterocolitis by inhibiting toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, C.; Fasano, A. Zonulin, a regulator of epithelial and endothelial barrier functions, and its involvement in chronic inflammatory diseases. Tissue Barriers 2016, 4, e1251384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A. Zonulin and its regulation of intestinal barrier function: The biological door to inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, S.; Kling, D.E.; Leone, S.; Lawlor, N.T.; Huang, Y.; Feinberg, S.B.; Hill, D.R.; Newburg, D.S. The human milk oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose modulates CD14 expression in human enterocytes, thereby attenuating LPS-induced inflammation. Gut 2016, 65, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Kiewiet, M.B.; Groeneveld, A.; Nauta, A.; de Vos, P. Human milk oligosaccharides and its acid hydrolysate LNT2 show immunomodulatory effects via TLRs in a dose-and structure-dependent way. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 59, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Guo, H.; Yan, J.; Liu, F.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Ren, F. Human milk oligosaccharides protect against necrotizing enterocolitis by inhibiting intestinal damage via increasing the proliferation of crypt cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1900262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wu, R.Y.; Horne, R.G.; Ahmed, A.; Lee, D.; Robinson, S.C.; Zhu, H.; Lee, C.; Cadete, M.; Johnson-Henry, K.C.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharides protect against necrotizing enterocolitis by activating intestinal cell differentiation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 2000519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Engen, P.A.; Leusink-Muis, T.; Van Ark, I.; Stahl, B.; Overbeek, S.A.; Garssen, J.; Naqib, A.; Green, S.J.; Keshavarzian, A.; et al. The combination of 2′-fucosyllactose with short-chain galacto-oligosaccharides and long-chain fructo-oligosaccharides that enhance influenza vaccine responses is associated with mucosal immune regulation in mice. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Courtade, L.; Han, S.; Lee, S.; Mian, F.M.; Buck, R.; Forsythe, P. Attenuation of food allergy symptoms following treatment with human milk oligosaccharides in a mouse model. Allergy 2015, 70, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverri, E.J.; Devitt, A.A.; Kajzer, J.A.; Baggs, G.E.; Borschel, M.W. Review of the clinical experiences of feeding infants formula containing the human milk oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paone, P.; Latousakis, D.; Terrasi, R.; Vertommen, D.; Jian, C.; Borlandelli, V.; Suriano, F.; Johansson, M.E.V.; Puel, A.; Bouzin, C.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharide 2′-fucosyllactose protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity by changing intestinal mucus production, composition and degradation linked to changes in gut microbiota and faecal proteome profiles in mice. Gut 2024, 73, 1632–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azagra-Boronat, I.; Massot-Cladera, M.; Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Knipping, K.; Van’t Land, B.; Tims, S.; Stahl, B.; Garssen, J.; Franch, À.; Castell, M.; et al. Immunomodulatory and prebiotic effects of 2′-fucosyllactose in suckling rats. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Gallardo, R.; Bottacini, F.; O’Neill, I.J.; Esteban-Torres, M.; Moore, R.; McAuliffe, F.M.; Cotter, P.D.; van Sinderen, D. Selective human milk oligosaccharide utilization by members of the Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum taxon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e00648-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, H.; Sato, Y.; Komatsu, Y.; Yamashita, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Kokubo, T. HMOs induce butyrate production of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii via cross-feeding by Bifidobacterium bifidum with different mechanisms for HMO types. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Wiele, T.; Van den Abbeele, P.; Ossieur, W.; Possemiers, S.; Marzorati, M. The simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem (SHIME®). In The Impact of Food Bioactives on Health: In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models; Verhoeckx, K., Cotter, P., López-Expósito, I., Kleiveland, C., Lea, T., Mackie, A., Requena, T., Swiatecka, D., Wichers, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y.; Kanayama, M.; Nakajima, S.; Hishida, Y.; Watanabe, Y. Sialyllactose enhances the short-chain fatty acid production and barrier function of gut epithelial cells via nonbifidogenic modification of the fecal microbiome in human adults. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Kanayama, M.; Nakajima, S.; Komatsu, Y.; Kokubo, T. Comparative analysis of fucosyllactose-induced changes in adult gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid production using the simulator of human intestinal microbial ecosystem model. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2025, 30, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuligoj, T.; Vigsnæs, L.K.; Van den Abbeele, P.; Apostolou, A.; Karalis, K.; Savva, G.M.; McConnell, B.; Juge, N. Effects of human milk oligosaccharides on the adult gut microbiota and barrier function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.T.; Steinert, R.E.; Duysburgh, C.; Ghyselinck, J.; Marzorati, M.; Dekker, P.J. In vitro effect of enzymes and human milk oligosaccharides on FODMAP digestion and fecal microbiota composition. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elison, E.; Vigsnæs, L.K.; Krogsgaard, L.R.; Rasmussen, J.; Sørensen, N.; McConnell, B.; Hennet, T.; Sommer, M.O.A.; Bytzer, P. Oral supplementation of healthy adults with 2′-O-fucosyllactose and lacto-N-neotetraose is well tolerated and shifts the intestinal microbiota. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 1356–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iribarren, C.; Törnblom, H.; Aziz, I.; Magnusson, M.K.; Sundin, J.; Vigsnæs, L.K.; Amundsen, I.D.; McConnell, B.; Seitzberg, D.; Öhman, L.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharide supplementation in irritable bowel syndrome patients: A parallel, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 32, e13920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.P.; Lee, M.L.; Rechtman, D.J.; Sun, A.K.; Autran, C.; Niklas, V. Human milk oligosaccharides modulate the intestinal microbiome of healthy adults. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Fan, L.; Zheng, N.; Blecker, C.; Delcenserie, V.; Li, H.; Wang, J. 2′-fucosyllactose ameliorates inflammatory bowel disease by modulating gut microbiota and promoting MUC2 expression. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 822020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.H.; Shin, C.S.; Yoon, J.W.; Jeon, S.M.; Song, Y.H.; Kim, K.-Y.; Kim, K. 2′-Fucosyllactose and 3-fucosyllactose alleviate interleukin-6-induced barrier dysfunction and dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis by improving intestinal barrier function and modulating the intestinal microbiome. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabinger, T.; Glaus Garzon, J.F.; Hausmann, M.; Geirnaert, A.; Lacroix, C.; Hennet, T. Alleviation of intestinal inflammation by oral supplementation with 2-fucosyllactose in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, C.P.; Ahmad, R.; Fulton, W.B.; Lopez, C.M.; Eke, B.O.; Scheese, D.; Duess, J.W.; Steinway, S.N.; Raouf, Z.; Moore, H.; et al. Human milk oligosaccharides reduce necrotizing enterocolitis-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2023, 325, G23–G41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrer, A.; Sprenger, N.; Kurakevich, E.; Borsig, L.; Chassard, C.; Hennet, T. Milk sialyllactose influences colitis in mice through selective intestinal bacterial colonization. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2843–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsson, O.S.; Peery, A.; Seitzberg, D.; Amundsen, I.D.; McConnell, B.; Simrén, M. Human milk oligosaccharides support normal bowel function and improve symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: A multicenter, open-label trial. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, e00276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.J.; Monteagudo-Mera, A.; Contractor, N.; Gibson, G.R. Impact of 2′-fucosyllactose on gut microbiota composition in adults with chronic gastrointestinal conditions: Batch culture fermentation model and pilot clinical trial findings. Nutrients 2021, 13, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.P.; Wijeyesekera, A.; Williams, C.M.; Theis, S.; van Harsselaar, J.; Rastall, R.A. Inulin-type fructans and 2′-fucosyllactose alter both microbial composition and appear to alleviate stress-induced mood state in a working population compared to placebo (maltodextrin): The EFFICAD trial, a randomized, controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 938–955, Correction in Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Li, H.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, N.; Delcenserie, V.; Wang, J. The milk active ingredient, 2′-fucosyllactose, inhibits inflammation and promotes MUC2 secretion in LS174T goblet cells in vitro. Foods 2023, 12, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natividad, J.M.; Marsaux, B.; Rodenas, C.L.G.; Rytz, A.; Vandevijver, G.; Marzorati, M.; Abbeele, P.V.D.; Calatayud, M.; Rochat, F. Human milk oligosaccharides and lactose differentially affect infant gut microbiota and intestinal barrier in vitro. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azagra-Boronat, I.; Massot-Cladera, M.; Knipping, K.; Van’t Land, B.; Stahl, B.; Garssen, J.; Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Franch, À.; Castell, M.; Pérez-Cano, F.J. Supplementation with 2′-FL and scGOS/lcFOS ameliorates rotavirus-induced diarrhea in suckling rats. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Qian, M.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, A.; Zhang, W. 2′-Fucosyllactose modulates the intestinal immune response to gut microbiota and buffers experimental colitis in mice: An integrating investigation of colonic proteomics and gut microbiota analysis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Komatsu, Y.; Furuichi, M.; Kokubo, T. Gastrointestinal Journey of Human Milk Oligosaccharides: From Breastfeeding Origins to Functional Roles in Adults. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010029

Komatsu Y, Furuichi M, Kokubo T. Gastrointestinal Journey of Human Milk Oligosaccharides: From Breastfeeding Origins to Functional Roles in Adults. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomatsu, Yosuke, Megumi Furuichi, and Takeshi Kokubo. 2026. "Gastrointestinal Journey of Human Milk Oligosaccharides: From Breastfeeding Origins to Functional Roles in Adults" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010029

APA StyleKomatsu, Y., Furuichi, M., & Kokubo, T. (2026). Gastrointestinal Journey of Human Milk Oligosaccharides: From Breastfeeding Origins to Functional Roles in Adults. Microorganisms, 14(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010029