Effects of Additives on Fermentation Quality, Nutritional Quality, and Microbial Diversity of Leymus chinensis Silage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Silage Preparation

2.2. Nutritional Composition and Fermentation Characteristics Analyses

2.3. Sequencing and Analysis of Microbial Diversity

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Different Additives on Fermentation Quality of Sheep Grass

3.2. Effects of Different Additives on Nutritional Components of Sheep Grass

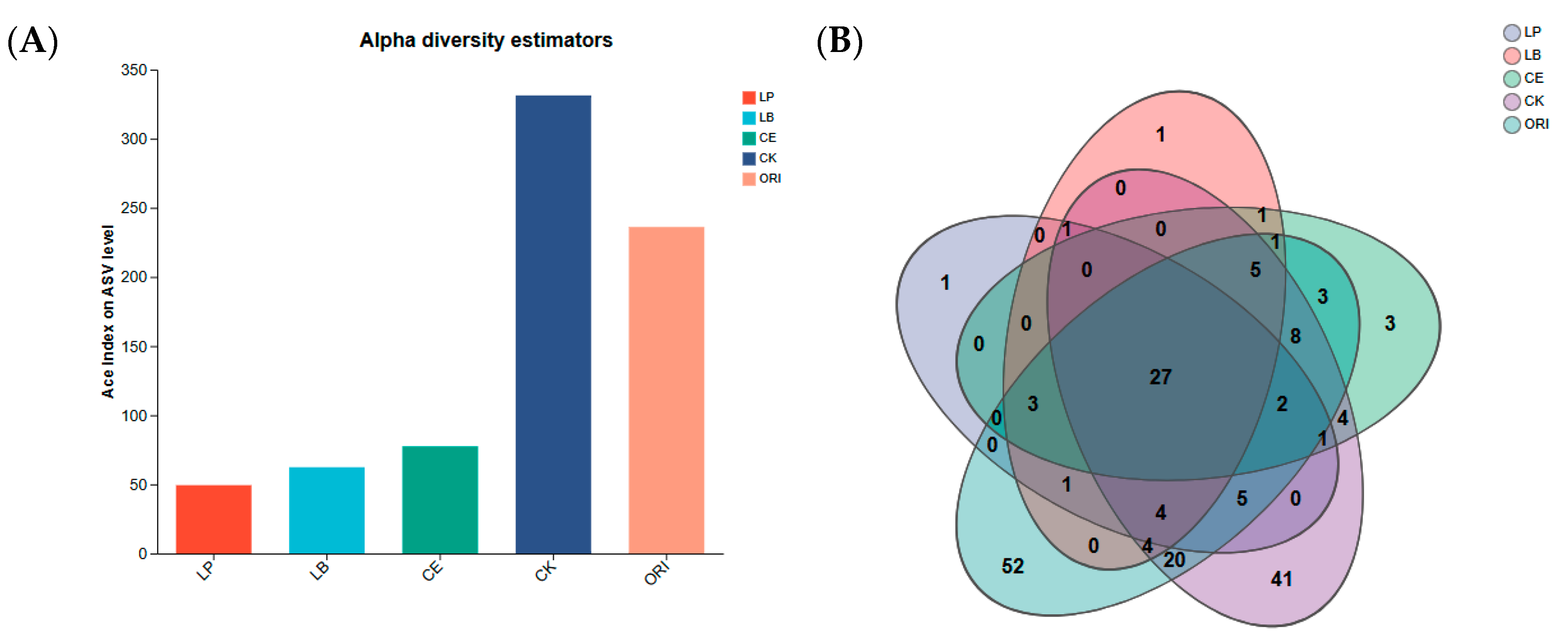

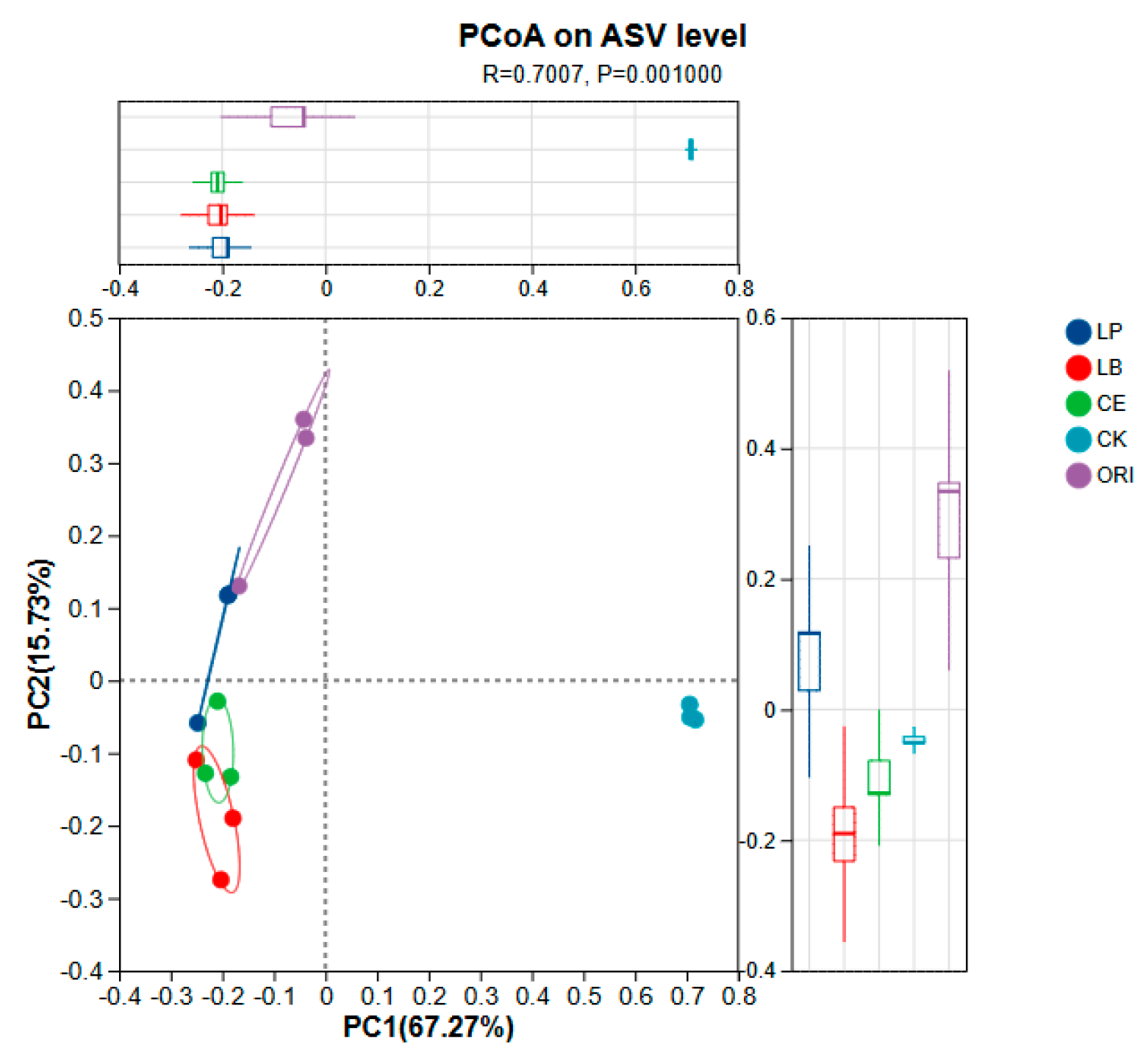

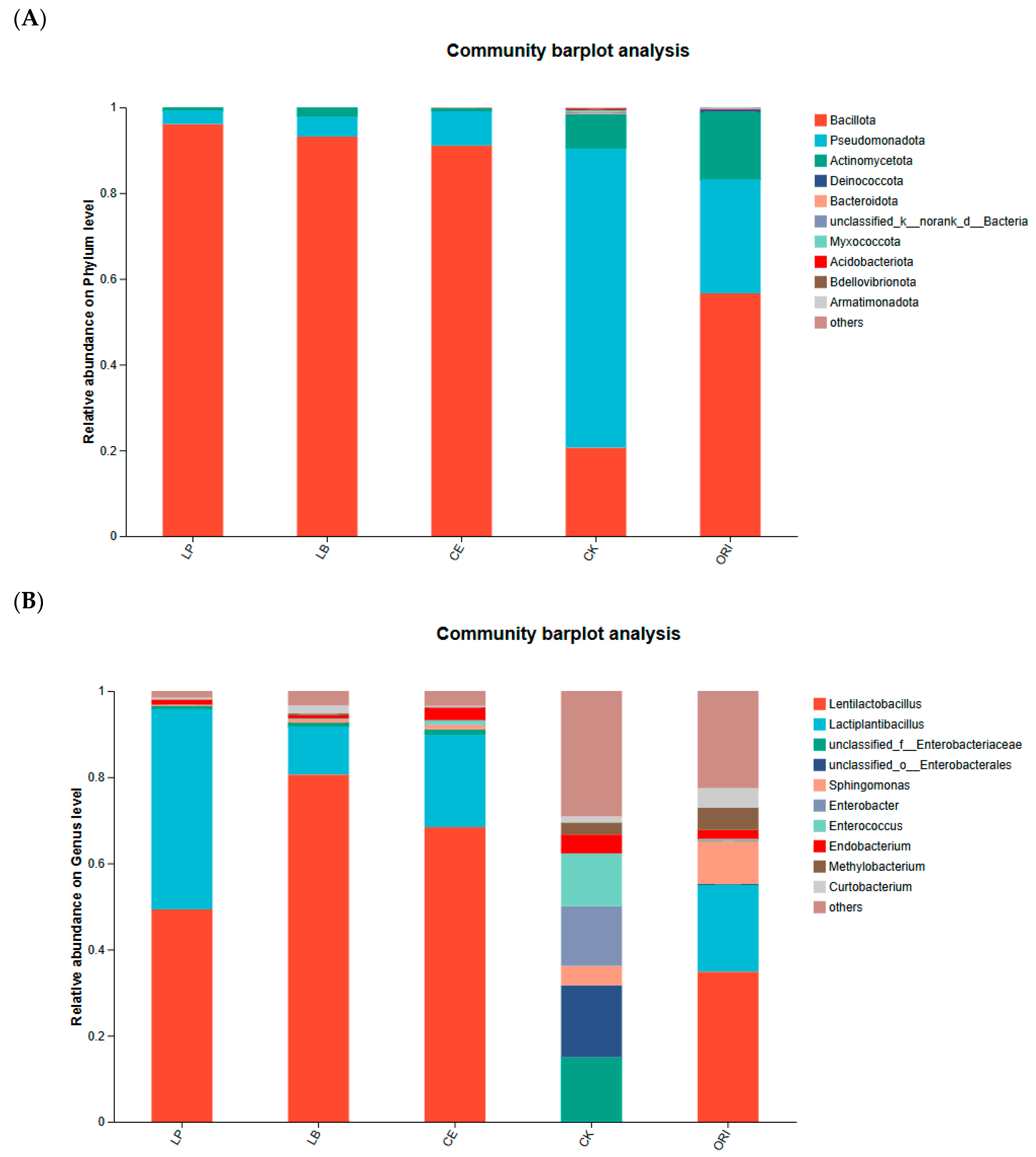

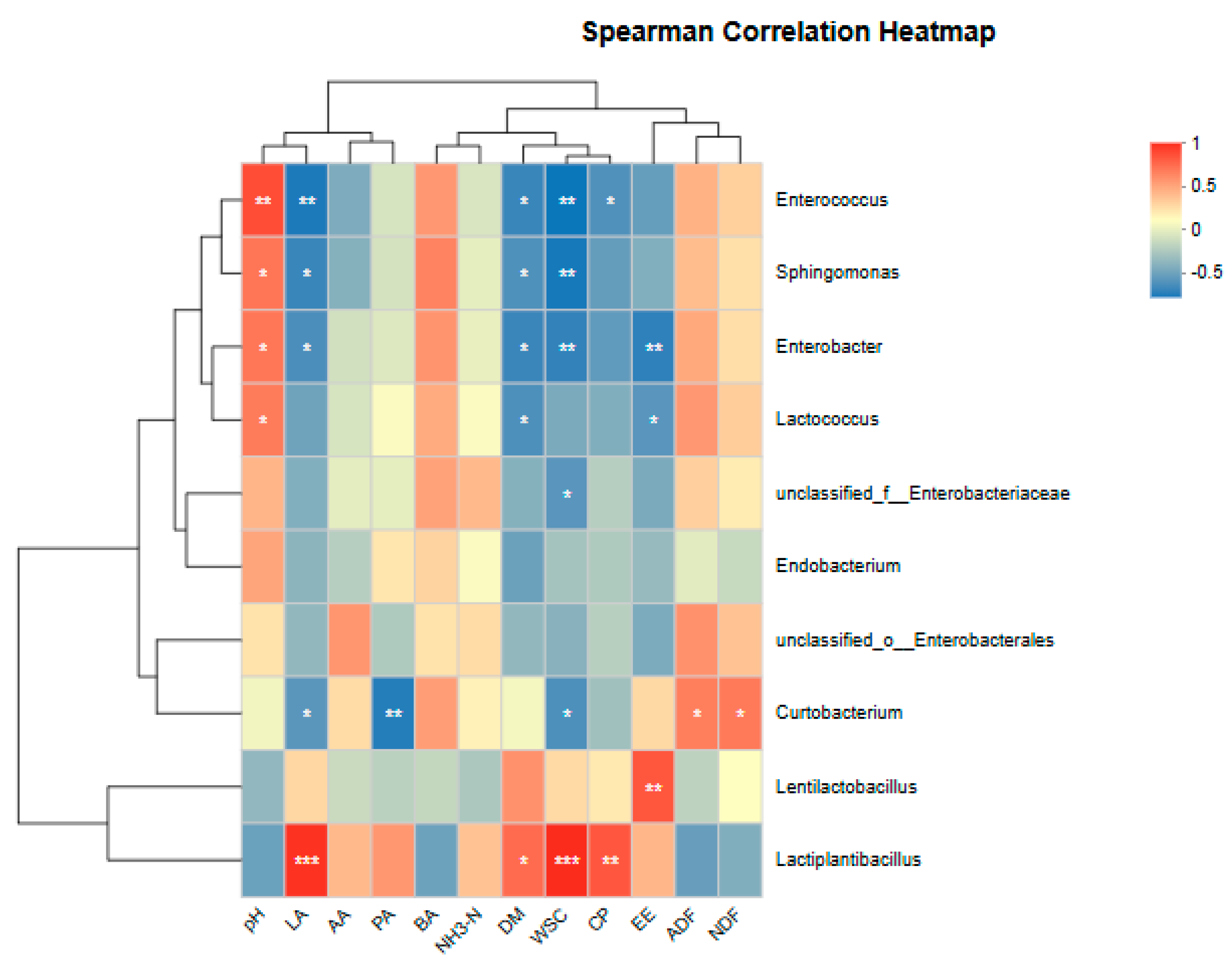

3.3. Effects of Different Additives on Microbial Diversity of Sheep Grass

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Li, X.; Liu, S.; Yuan, G.; Zhao, P.; Yang, W.; Jia, J.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, G. Comparative transcriptome analysis provides insights into the distinct germination in sheepgrass (Leymus chinensis) during seed development. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 139, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, K.F.M. Perennial pasture grasses—An historical review of their introduction, use and development for southern Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014, 65, 691–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. Sheepgrass (Leymus chinensis): An Environmentally Friendly Native Grass for Animals; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Li, X. How do arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance drought resistance of Leymus chinensis? BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shao, T.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Bai, C. Advances in Grass and Forage Processing and Production in China. In Grassland and Forages in China; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 97–143. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Zuo, S.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, F. Expansion improved the physical and chemical properties and in-vitro rumen digestibility of buckwheat straw. Animals 2023, 14, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Untargeted metabolome analyses revealed potential metabolic mechanisms of Leymus chinensis in response to simulated animal feeding. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 3456–3464. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Zhao, M.; Sun, P.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q. Effects of different additives on fermentation characteristics, nutrient composition and microbial communities of Leymus chinensis silage. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, T.F.; Daniel, J.L.P.; Adesogan, A.T.; McAllister, T.A.; Huhtanen, P. Silage review: Unique challenges of silages made in hot and cold regions. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4001–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhuo, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, G. Effect of different harvest times and processing methods on the vitamin content of Leymus. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1424334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, P.; Henderson, A.R.; Heron, S.; Anderson, R. The biochemistry of silage. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1991, 7, 317–318. [Google Scholar]

- Kung, L.; Shaver, R.; Grant, R.; Smith, M. Silage review: Interpretation of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4020–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, M.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. The feasibility and effects of exogenous epiphytic microbiota on the fermentation quality and microbial community dynamics of whole crop corn. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 306, 123123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.G.; Cao, W.K.; Ri, W.D.; Zhang, L. Profiling of metabolome and bacterial community dynamics in ensiled Medicago sativa inoculated without or with Lactobacillus plantarum or Lactobacillus buchneri. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunière, L.; Sindou, J.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Forano, E. Silage processing and strategies to prevent persistence of undesirable microorganisms. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2013, 182, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhao, M.; Song, J.; Gao, D.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Yu, Z.; Bai, C.; Wang, Y. Effect of Cordyceps militaris Residue and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on Fermentation Quality and Bacterial Community of Alfalfa Silage. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Du, S.; Sun, L.; Cheng, Q.; Hao, J.; Lu, Q.; Ge, G.; Wang, Z.; Jia, Y.; Bai, Y. Effects of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Molasses Additives on Dynamic Fermentation Quality and Microbial Community of Native Grass Silage. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 830121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, D.; Oktarina, N.; Chen, P.T.; Chang, J.S. Fermentative lactic acid production from seaweed hydrolysate using Lactobacillus sp. and Weissella sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126166. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, L.; Xie, Z.; Hu, L.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Z. Cellulase interacts with Lactobacillus plantarum to affect chemical composition, bacterial communities, and aerobic stability in mixed silage of high-moisture amaranth and rice straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Jing, Y.Y.; Yang, G.; Liu, H. Effects of inoculants on the quality of alfalfa silage. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1541454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Érica, S.D.B.; Martinele, D.C.; Mauro, E.S.; Bernardes, T.F. The effects of Lactobacillus hilgardii 4785 and Lactobacillus buchneri 40788 on the microbiome, fermentation, and aerobic stability of corn silage ensiled for various times. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 10678–10698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoso, B.; Hariadi, B.T.; Lekitoo, M.N.; Soetanto, H. Fermentation characteristics, in vitro nutrient digestibility, and methane production of oil palm frond-based complete feed silage treated with cellulase. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2024, 12, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Na, N.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Wu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yin, G.; Liu, S.; Liu, Z. Impact of Packing Density on the Bacterial Community, Fermentation, and In Vitro Digestibility of Whole-Crop Barley Silage. Agriculture 2021, 11, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.A. An automated procedure for the determination of soluble carbohydrates in herbage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1977, 28, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, G.A.; Kang, J.H. Automated Simultaneous Determination of Ammonia and Total Amino Acids in Ruminal Fluid and in Vitro Media. J. Dairy Sci. 1980, 63, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadeh-Cigari, F.; Khorvash, M.; Ghorbani, G.R.; Ghasemi, E. Interactive effects of molasses by homofermentative and heterofermentative inoculants on fermentation quality, nitrogen fractionation, nutritive value and aerobic stability of wilted alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) silage. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 98, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.N.; Li, S.Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum inoculation on the quality and bacterial community of whole-crop corn silage at different harvest stages. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, N.K.; Kung, L., Jr. The effect of Lactobacillus buchneri, Lactobacillus plantarum, or a chemical preservative on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn silage. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, W.Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Wang, C. Effects of Lentilactobacillus buchneri combined with different sugars on nutrient composition, fermentation quality, rumen degradation rate, and aerobic stability of alfalfa silage. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2023, 32, 122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Bai, Y.; Li, J. Effects of fibrolytic enzyme additives on fermentation quality and microbial community of sorghum silage. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121619. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, W.C.; Yang, F.Y.; Undersander, D.J.; Guo, X.S. Fermentation characteristics and nutritive value of low-dry matter alfalfa silage treated with cellulase and lactic acid bacteria. Grassl. Sci. Eur. 2020, 25, 321–323. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowarek, K.; Lipińska, E.; Hać-Szymańczuk, E.; Rudziak, A. Propionibacterium spp.—Source of propionic acid, vitamin B12, and other metabolites important for the industry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 515–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Deng, X.; Hao, J.; Wang, M.; Ge, G. Analysis of the formation mechanism and regulation pathway of oat silage off-flavor based on microbial-metabolite interaction network. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 464. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X.; Liu, X.; Wan, K.; Li, C. Mechanisms of Clostridioides difficile Glucosyltransferase Toxins and their Roles in Pathology: Insights and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1641564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.J.; Li, L.; Millar, A.H. Metabolic labeling with stable isotopes for studying protein turnover. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2016, 4, 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.M.; Ding, Z.T.; Wang, M.S.; Li, F. Characterization of the microbial community, metabolome and biotransformation of phenolic compounds of sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia) silage ensiled with or without inoculation of Lactobacillus plantarum. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 316, 123910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukamuhirwa, M.L.; Hatungimana, E.; Latre, J.; Bauters, M. Piloting locally made microsilos to monitor the silage fermentation quality of conserved forage in Rwanda. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, G.Q.; Wei, S.N.; Li, M. Changes in fermentation pattern and quality of Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum L.) silage by wilting and inoculant treatments. Anim. Biosci. 2020, 34, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Enhancing alfalfa and sorghum silage quality using agricultural wastes: Fermentation dynamics, microbial communities, and functional insights. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 728, Erratum in BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 785. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.Y.; Ungerfeld, E.; Ouyang, Z.; Tan, Z.L. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum inoculation on chemical composition, fermentation, and bacterial community composition of ensiled sweet corn whole plant or stover. Fermentation 2022, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. In-depth proteomic analysis of alfalfa silage inoculated with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum reveals protein transformation mechanisms and optimizes dietary nitrogen utilization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 142638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, B.; Liu, G.; Li, J. Effect of Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus plantarum on solid-state fermentation of soybean meal. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 6070–6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, T.; Wang, H.; Zheng, M.; Li, F. Effects of microbial enzymes on starch and hemicellulose degradation in total mixed ration silages. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 30, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, H. An adaptive microbiome α-diversity-based association analysis method. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 18026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, H. Antimicrobial activity enabled by chitosan-ε-polylysine-natamycin and its effect on microbial diversity of tomato scrambled egg paste. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100872. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, J. Lactobacillus plantarum inoculants delay spoilage of high moisture alfalfa silages by regulating bacterial community composition. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ke, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C. Effects of Bacillus coagulans and Lactobacillus plantarum on the fermentation quality, aerobic stability and microbial community of triticale silage. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.J.; Li, J.F.; Dong, Z.H.; Shao, T. The reconstitution mechanism of napier grass microbiota during the ensiling of alfalfa and their contributions to fermentation quality of silage. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 297, 122391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Long, S.H.; Li, X.F.; Yuan, X.J.; Pan, J.X. The effect of early and delayed harvest on dynamics of fermentation profile, chemical composition, and bacterial community of King grass silage. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 864649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Jiang, C.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y. Effects of cellulase or Lactobacillus plantarum on ensiling performance and bacterial community of sorghum straw. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouin, P.; da Silva, É.B.; Tremblay, J.; Castex, M. Inoculation with Lentilactobacillus buchneri alone or in combination with Lentilactobacillus hilgardii modifies gene expression, fermentation profile, and starch digestibility in high-moisture corn. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1253588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, H.; Guo, Q.; Liu, X. Modulation of the microbial community and the fermentation characteristics of wrapped natural grass silage inoculated with composite bacteria. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Tahir, M.; Huang, F.; Li, Y. Fermentation quality, amino acids profile, and microbial communities of whole-plant soybean silage in response to Lactiplantibacillus plantarum B90 alone or in combination with functional microbes. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1458287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Zhang, G.; Shi, J.; Wang, L. Keystone taxa Lactiplantibacillus and Lacticaseibacillus directly improve the ensiling performance and microflora profile in co-ensiling cabbage byproduct and rice straw. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hu, M.; Li, X. Effects of Biological Additives on the Fermentation Quality and Microbial Community of High-Moisture Oat Silage. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, C.; Peter, M.; Peter, H.; Smith, A. Enterococcus faecalis V583 cell membrane protein expression to alkaline stress. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Yu, C.; Song, X.; Gao, Y. Analysis of the Impact of Acidity and Alkalinity on the Microbial Community Structure in Urban Rivers. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 19, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Bo, X.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Unraveling Novel Acid Tolerance Mechanisms in Lactococcus lactis through Physiological and Multi-Omics Analyses. LWT 2025, 232, 118387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Bakyrbay, S.; Liu, L.; Wang, J. Microbiota Succession and Chemical Composition Involved in Lactic Acid Bacteria-Fermented Pickles. Fermentation 2023, 9, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, B.; Gentu, G.; Zhijun, W.; Li, M. Effect of isolated lactic acid bacteria on the quality and bacterial diversity of native grass silage. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1160369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Jia, Y.; Ge, G.; Wang, Z. Microbiomics and volatile metabolomics-based investigation of changes in quality and flavor of oat (Avena sativa L.) silage at different stages. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1278715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, Z.J.; Liu, Y. Effect of different regions on fermentation profiles, microbial communities, and their metabolomic pathways and properties in Italian ryegrass silage. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1076499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. Influence of Lactobacillus plantarum and cellulase on fermentation quality and microbial community in mixed silage of Solanum rostratum and alfalfa. Front. Microbiomes 2025, 3, 1510774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, H.R.; Li, X. Influence on the fermentation quality, microbial diversity, and metabolomics in the ensiling of sunflower stalks and alfalfa. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1333207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Shao, T.; Ouyang, J.; Liu, Y. Optimizing fermentation quality via lignocellulose degradation: Synergistic effects of fibrolytic additives and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on Elymus dahuricus silage. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pH | LA | AA | PA | BA | NH3-N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/kg DM | g/kg DM | g/kg DM | g/kg DM | %FW | ||

| LP | 4.26 ± 0.02 B | 65.24 ± 0.42 A | 25.81 ± 0.94 A | 7.23 ± 0.34 B | 0.00 ± 0.00 B | 0.83 ± 0.00 A |

| LB | 4.34 ± 0.05 B | 49.59 ± 0.38 C | 15.66 ± 0.55 BC | 4.77 ± 0.38 C | 0.11 ± 0.11 B | 0.59 ± 0.13 A |

| CE | 4.68 ± 0.03 A | 54.64 ± 1.93 B | 12.33 ± 1.21 C | 11.89 ± 0.42 A | 0.00 ± 0.00 B | 0.63 ± 0.00 A |

| CK | 4.72 ± 0.05 A | 41.90 ± 1.34 D | 16.04 ± 1.14 B | 5.40 ± 0.29 C | 1.72 ± 0.94 A | 0.71 ± 0.00 A |

| p-value | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | <0.0001 | 0.0724 | 0.4972 |

| DM | WSC | CP | EE | ADF | NDF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/kgFW | g/kgDM | g/kgDM | g/kgDM | g/kgDM | g/kgDM | |

| LP | 581.62 ± 5.62 A | 24.76 ± 0.18 B | 70.94 ± 0.43 A | 19.12 ± 0.09 B | 438.53 ± 0.44 C | 656.51 ± 2.73 B |

| LB | 561.88 ± 9.69 AB | 19.58 ± 0.31 C | 63.98 ± 1.17 B | 20.84 ± 0.33 A | 450.74 ± 4.61 B | 703.03 ± 2.71 A |

| CE | 541.05 ± 7.13 B | 24.02 ± 0.25 B | 64.29 ± 0.32 B | 18.37 ± 0.41 BC | 428.81 ± 4.16 C | 628.43 ± 4.08 C |

| CK | 494.73 ± 6.44 B | 12.81 ± 0.32 C | 62.45 ± 0.46 B | 17.49 ± 0.54 C | 453.53 ± 3.53 B | 698.74 ± 1.43 A |

| ORI | 581.60 ± 5.57 A | 46.44 ± 0.29 A | 70.51 ± 0.94 A | 20.72 ± 0.36 A | 478.92 ± 3.40 A | 704.82 ± 5.88 A |

| p-value | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | <0.0001 | 0.0724 | 0.4972 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qi, M.; Wang, Z.; Jia, Y.; Ge, G. Effects of Additives on Fermentation Quality, Nutritional Quality, and Microbial Diversity of Leymus chinensis Silage. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010027

Qi M, Wang Z, Jia Y, Ge G. Effects of Additives on Fermentation Quality, Nutritional Quality, and Microbial Diversity of Leymus chinensis Silage. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Mingga, Zhijun Wang, Yushan Jia, and Gentu Ge. 2026. "Effects of Additives on Fermentation Quality, Nutritional Quality, and Microbial Diversity of Leymus chinensis Silage" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010027

APA StyleQi, M., Wang, Z., Jia, Y., & Ge, G. (2026). Effects of Additives on Fermentation Quality, Nutritional Quality, and Microbial Diversity of Leymus chinensis Silage. Microorganisms, 14(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010027