Antimycobacterial Mechanisms and Anti-Virulence Activities of Polyphenolic-Rich South African Medicinal Plants Against Mycobacterium smegmatis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Plant Collection

2.3. Extraction of Plant Material

2.4. Quantification of Polyphenolics

2.4.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.4.2. Total Tannin Content (TTC)

2.4.3. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

2.4.4. Total Flavonol Content (TFlC)

2.5. Quantitative Antioxidant Activity

2.5.1. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Assay

2.5.2. Ferric-Reducing Power Assay

2.6. Antimycobacterial Activity

2.6.1. Microorganism Used in This Study

2.6.2. Microdilution Assay

2.6.3. Combinational Effects of Plant Extracts

2.6.4. Evaluation of Growth Kinetics During Treatment

2.7. Antimycobacterial Mechanism of the Plant Extracts

2.7.1. Measurement of Intracellular Protein and DNA Leakage

2.7.2. Measurement of INT-Dehydrogenase Relative Activity

2.8. Antibiofilm Activity Assays

2.8.1. Prevention of Initial Cell Attachment

2.8.2. Prevention of Biofilm Formation

2.8.3. Eradication of Pre-Formed Biofilms

2.8.4. Crystal Violet Staining Assay

2.9. Antimotility Activity

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

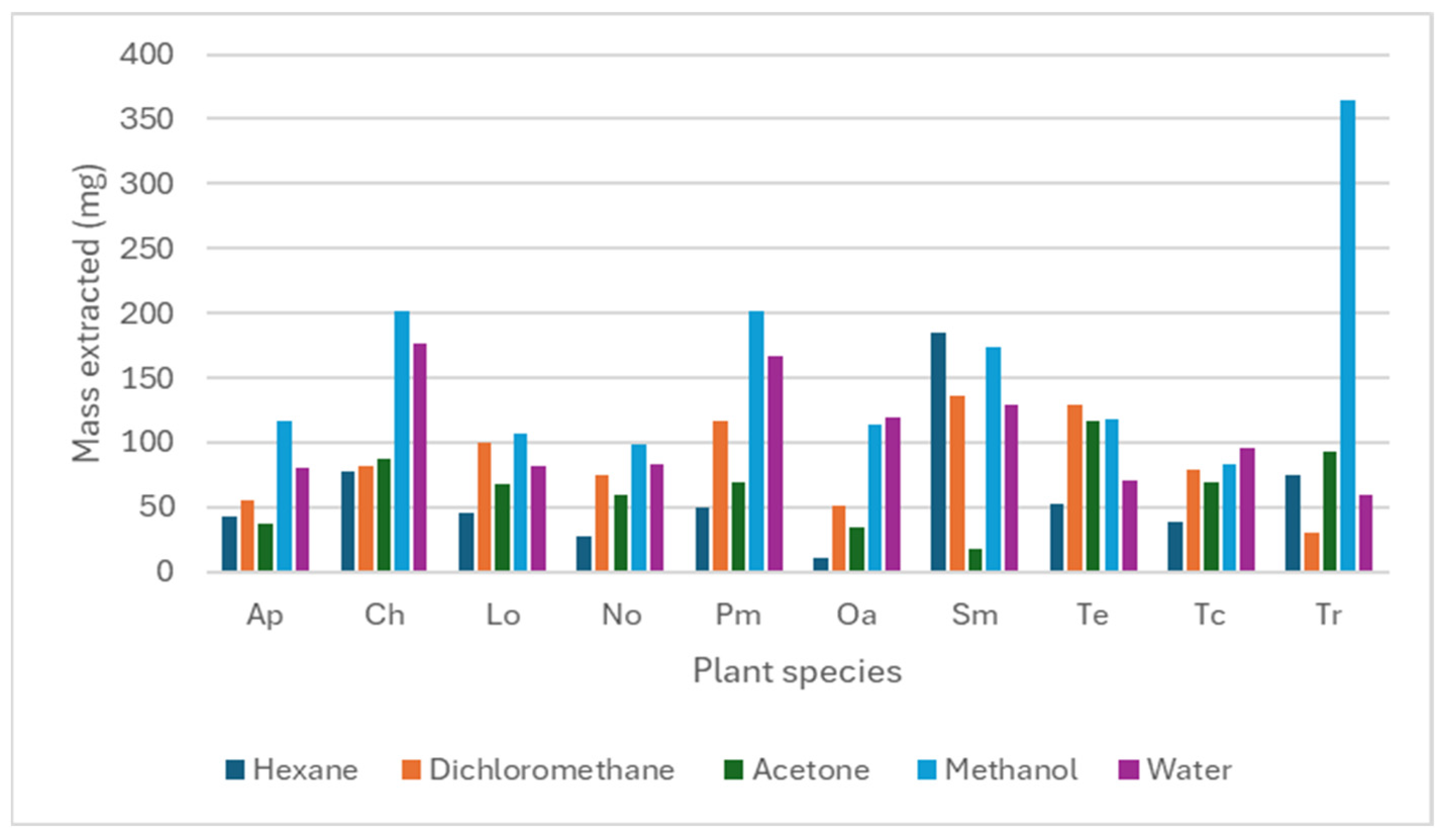

3.1. Extract Mass Obtained from Plant Material

3.2. Total Polyphenolic Content of Acetone Plant Extracts

3.3. Antioxidant Activity of the Different Plant Extracts

3.4. Antimycobacterial Activity Screening

3.5. Combinational Effects

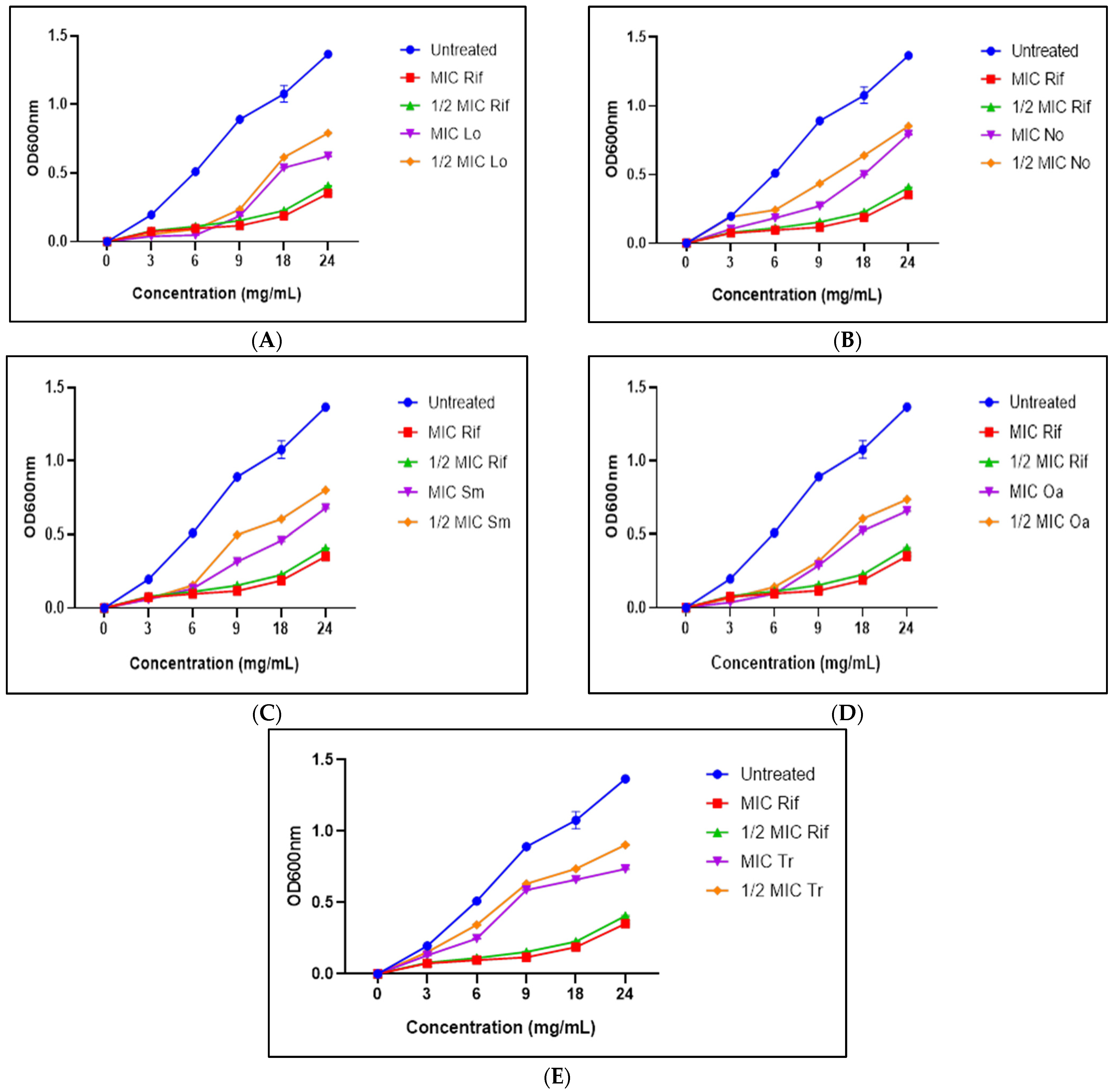

3.6. Growth Kinetics

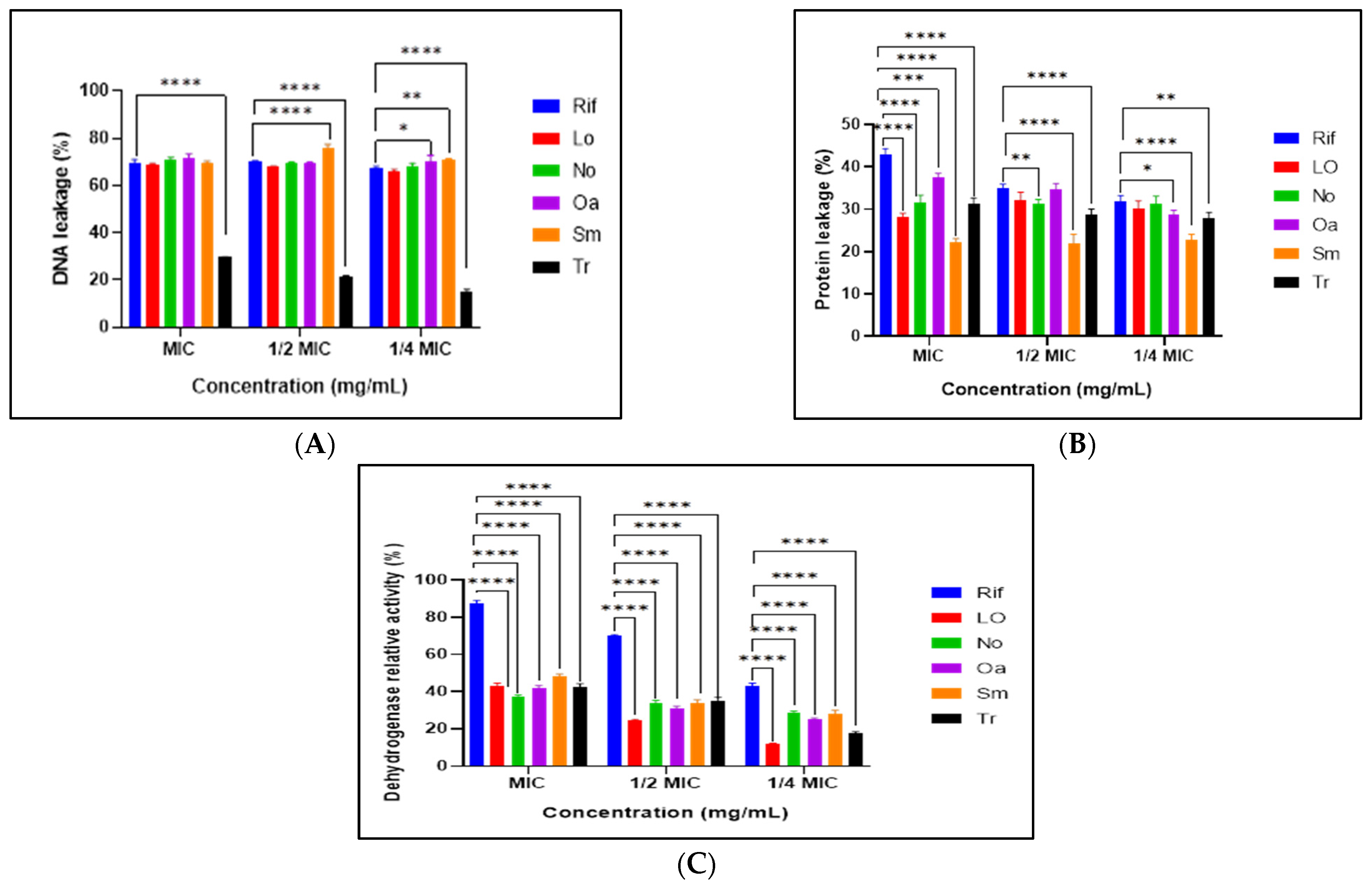

3.7. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Action of Selected Extracts

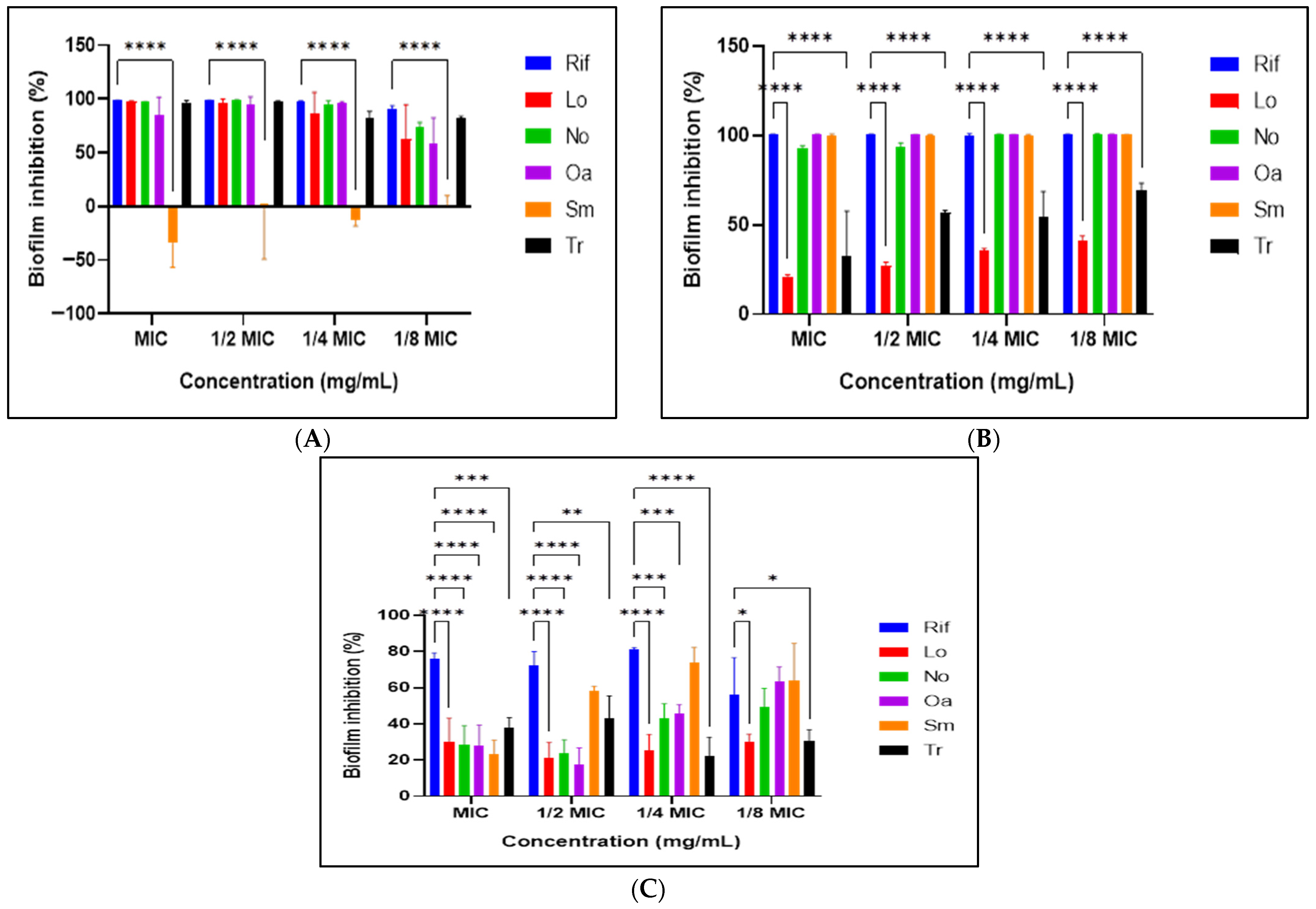

3.8. Antibiofilm Activity Assay

3.9. Antimotility Activity of the Selected Plant Extracts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| EC50 | Half maximal effective concentration |

| mg GAE/g | Milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of extract |

| mg QE/g | Milligrams of quercetin equivalents per gram of extract |

| OD600 | Optical density at 600 nanometers |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/TB-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Baykan, A.H.; Sayiner, H.S.; Aydin, E.; Koc, M.; Inan, I.; Erturk, S.M. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: An old but resurgent problem. Insights Imaging 2022, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davuluri, M.; Yarlagadda, V.S.T. Novel device for enhancing tuberculosis diagnosis for faster, more accurate screening results. Int. J. Innov. Eng. Res. Technol. 2024, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, I.; Boeree, M.; Chesov, D.; Dheda, K.; Günther, G.; Horsburgh, C.R., Jr.; Kherabi, Y.; Lange, C.; Lienhardt, C.; McIlleron, H.M.; et al. Recent advances in the treatment of tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Misba, L.; Khan, A.U. Antibiotics versus biofilm: An emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, S.R. Computational identification of the proteins associated with quorum sensing and biofilm formation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Liu, M.; Yu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Dai, Y.; Luo, H.; Huang, Q.; Fan, L.; Xie, J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv1515c antigen enhances survival of M. smegmatis within macrophages by disrupting the host defence. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 153, 104778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Jain, M.; Singh, S.V.; Dhama, K.; Aseri, G.K.; Jain, N.; Datta, M.; Kumar, N.; Yadav, P.; Jayaraman, S.; et al. Plants as future source of anti-mycobacterial molecules and armour for fighting drug resistance. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2015, 10, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.S.; Huang, X.; Birhanie, Z.M.; Gao, G.; Feng, X.; Yu, C.; Chen, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, K.; Wang, X.; et al. Phytochemical composition, antioxidant, antibacterial, and enzyme inhibitory activities of various organic extracts from Apocynum hendersonii (Hook. f.) Woodson. Plants 2022, 11, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, S.; Medhin, G.; Asres, A.; Abebe, G.; Ameni, G. Traditional medicinal plants used in the treatment of tuberculosis in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhir, R.; Khurana, M.; Singhal, N.K. Potential benefits of phytochemicals from Azadirachta indica against neurological disorders. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 146, 105023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Kumar, M.M.; Bisht, D.; Kaushik, A. Plants in our combating strategies against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Progress made and obstacles met. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, I.E.; Van Vuuren, S.F. The traditional use of southern African medicinal plants in the treatment of viral respiratory diseases: A review of the ethnobotany and scientific evaluations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 262, 113194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Qureshi, K.A.; Jameel Pasha, S.B.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Aspatwar, A.; Parkkila, S.; Alanazi, S.; Atiya, A.; Khan, M.M.U.; Venugopal, D. Medicinal plants as therapeutic alternatives to combat Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A comprehensive review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambe, V.D.; Bhambar, R.S. Estimation of total phenol, tannin, alkaloid and flavonoid in Hibiscus tiliaceus Linn. wood extracts. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2014, 2, 2321–6182. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, E.; Salim, K.A.; Lim, L.B. Phytochemical screening, total phenolics and antioxidant activities of bark and leaf extracts of Goniothalamus velutinus (Airy Shaw) from Brunei Darussalam. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2015, 27, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigayo, K.; Mojapelo, P.E.L.; Mnyakeni-Moleele, S.; Misihairabgwi, J.M. Phytochemical and antioxidant properties of different solvent extracts of Kirkia wilmsii tubers. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2016, 6, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, M.; Ruckmani, K. Ferric reducing anti-oxidant power assay in plant extract. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2016, 11, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloff, J.N. A sensitive and quick microplate method to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration of plant extracts for bacteria. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vuuren, S.; Viljoen, A. Plant-based antimicrobial studies–methods and approaches to study the interaction between natural products. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 1168–1182, Erratum in Planta Med. 2012, 78, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; He, L.; Zhan, Y.; Zang, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C.; Xin, Y. The effect of MSMEG_6402 gene disruption on the cell wall structure of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microb. Pathog. 2011, 51, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machingauta, A.; Mukanganyama, S. Antibacterial Activity and Proposed Mode of Action of Extracts from Selected Zimbabwean Medicinal Plants against Acinetobacter baumannii. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 2024, 8858665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Xuan, X.T.; Li, J.; Chen, S.G.; Liu, D.H.; Ye, X.Q.; Shi, J.; Xue, S.J. Disinfection efficacy and mechanism of slightly acidic electrolyzed water on Staphylococcus aureus in pure culture. Food Control 2016, 60, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, Z.G.; Barisci, S.; Dinc, O. Mechanisms of the Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis inactivation by ozone. LWT 2019, 100, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famuyide, I.M.; Aro, A.O.; Fasina, F.O.; Eloff, J.N.; McGaw, L.J. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of acetone leaf extracts of nine under-investigated South African Eugenia and Syzygium (Myrtaceae) species and their selectivity indices. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djordjevic, D.; Wiedmann, M.; McLandsborough, L.A. Microtiter plate assay for assessment of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2950–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caigoy, J.C.; Xedzro, C.; Kusalaruk, W.; Nakano, H. Antibacterial, antibiofilm, and antimotility signatures of some natural antimicrobials against Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nile, S.H.; Nile, A.S.; Keum, Y.S. Total phenolics, antioxidant, antitumor, and enzyme inhibitory activity of Indian medicinal and aromatic plants extracted with different extraction methods. 3 Biotech. 2017, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.S.; Liew, R.K.; Jusoh, A.; Chong, C.T.; Ani, F.N.; Chase, H.A. Progress in waste oil to sustainable energy, with emphasis on pyrolysis techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Jayakody, J.T.M.; Kim, J.I.; Jeong, J.W.; Choi, K.M.; Kim, T.S.; Seo, C.; Azimi, I.; Hyun, J.; Ryu, B. The influence of solvent choice on the extraction of bioactive compounds from Asteraceae: A comparative review. Foods 2024, 13, 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.R.; Haque, M. Preparation of medicinal plants: Basic extraction and fractionation procedures for experimental purposes. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2020, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnyambo, N. Evaluation of Phytochemical Composition of Two Nematicidal Plants (Maerua angolensis and Tabernaemontana elegans) Extracts. 2023. Available online: http://onehealth.usamv.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/7-One-Health_Oral_presentation_2023-NM-MNYAMBO.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Lopez-Corona, A.V.; Valencia-Espinosa, I.; González-Sánchez, F.A.; Sánchez-López, A.L.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Garcia-Varela, R. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Cytotoxic Activity of Phenolic Compound Family Extracted from Raspberries (Rubus idaeus): A General Review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptarini, N.M.; Pratiwi, R.; Maisyarah, I.T. Colorimetric method for total phenolic and flavonoid content determination of fig (Ficus carica L.) leaves extract from West Java, Indonesia. Rasayan J. Chem. 2022, 15, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; He, W.; Fan, X.; Guo, A. Biological function of plant tannin and its application in animal health. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 803657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebaya, A.; Belghith, S.I.; Baghdikian, B.; Leddet, V.M.; Mabrouki, F.; Olivier, E.; Kalthoum Cherif, J.; Ayadi, M.T. Total phenolic, total flavonoid, tannin content, and antioxidant capacity of Halimium halimifolium (Cistaceae). J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 5, 052–057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpalo, A.E.; Saloufou, I.K.; Eloh, K.; Kpegba, K. Wound healing biomolecules present in four proposed soft aqueous extractions of Ageratum conyzoides Linn. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2020, 14, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanyonga, S.K.; Opoku, A.; Lewu, F.B.; Oyedeji, A.O.; Singh, M. Chemical composition, antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of the essential oils of the leaves and stem of Tarchonanthus camphoratus. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 7, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashilo, C.M.; Sibuyi, N.R.; Botha, S.; Meyer, M.; Razwinani, M.; Motaung, K.S.; Madiehe, A.M. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using a Cocktail Aqueous Extract of Capparis sepiaria Root and Tabernaemontana elegans Bark. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202404781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouamnina, A.; Alahyane, A.; Elateri, I.; Boutasknit, A.; Abderrazik, M. Relationship between phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of some moroccan date palm fruit varieties (Phoenix dactylifera L.): A two-year study. Plants 2024, 13, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noche, C.D.; Dieu, L.N.; Djamen, P.C.; Kwetche, P.F.; Pefura-Yone, W.; Mbacham, W.; Etoa, F.X. Variation of some antioxidant biomarkers in Cameroonian patients treated with first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019, 13, 2245–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjitha, J.; Rajan, A.; Shankar, V. Features of the biochemistry of Mycobacterium smegmatis, as a possible model for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasingam, N. Mycobacterium smegmatis: Exploring its Similarities with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mycobact. Dis. 2023, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlala, M.S.; Moganedi, K.L.; Masoko, P. In Vitro Phytochemical, Antioxidant Activity and Antimycobacterial Potentials of Selected Medicinal Plants Commonly Used for Respiratory Infections and Related Symptoms in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025, 25, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Pires, D.; Aínsa, J.A.; Gracia, B.; Mulhovo, S.; Duarte, A.; Anes, E.; Ferreira, M.J.U. Antimycobacterial evaluation and preliminary phytochemical investigation of selected medicinal plants traditionally used in Mozambique. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P. Plant-Derived Antimicrobials and Their Crucial Role in Combating Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sao, M. Checkerboard Method for in vitro Synergism Testing of Three Antimicrobials against Multidrug-Resistant and Extremely Drug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Chim. Pharm. Indica 2023, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N. Synergy, Additive Effects, and Antagonism of Drugs with Plant Bioactive Compounds. Drugs Drug Candidates 2025, 4, 4, Erratum in Drugs Drug Candidates 2025, 4, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, C.A.; Cromarty, A.D.; Steenkamp, V. Effect of an alkaloidal fraction of Tabernaemontana elegans (Stapf.) on selected micro-organisms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Vuuren, S.F.; Viljoen, A.M. Interaction between the non-volatile and volatile fractions on the antimicrobial activity of Tarchonanthus camphoratus. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2009, 75, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Rakholiya, K. Combination therapy: Synergism between natural plant extracts and antibiotics against infectious diseases. Sci. Against Microb. Pathog. Commun. Curr. Res. Technol. Adv. 2011, 1, 520–529. [Google Scholar]

- Daglia, M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; De Martino, L.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V. Effect of essential oils on pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1451–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peloquin, C.A.; Davies, G.R. The treatment of tuberculosis. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 110, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Cai, J.; Chen, H.; Zhong, Q.; Hou, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, W. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of linalool against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 141, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.J.; Huang, Z.H.; Liu, D. Preparation of dihydromyricetin-Ag+ nanoemulsion and its inhibitory effect and mechanism on Staphylococcus aureus. Food Sci. 2020, 41, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusengeri, A.; Khan, A.; Tastan Bishop, Ö. The structural basis of mycobacterium tuberculosis RpoB drug-resistant clinical mutations on rifampicin drug binding. Molecules 2022, 27, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugayi, L.C.; Mukanganyama, S. Antimycobacterial and Antifungal Activities of Leaf Extracts From Trichilia emetica. Scientifica 2024, 2024, 8784390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, E.A.; Yano, T.; Li, L.S.; Avarbock, D.; Avarbock, A.; Helm, D.; McColm, A.A.; Duncan, K.; Lonsdale, J.T.; Rubin, H. Inhibitors of type II NADH: Menaquinone oxidoreductase represent a class of antitubercular drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 4548–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushnie, T.T.; Lamb, A.J. Recent advances in understanding the antibacterial properties of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurdle, J.G.; O’Neill, A.J.; Chopra, I.; Lee, R.E. Targeting bacterial membrane function: An underexploited mechanism for treating persistent infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Huerta, M.T.; Pérez-Campos, E.; Pérez-Campos Mayoral, L.; Vásquez Martínez, I.P.; Reyna González, W.; Jarquín González, E.E.; Aldossary, H.; Alhabib, I.; Yamani, L.Z.; Elhadi, N.; et al. Proactive Strategies to Prevent Biofilm-Associated Infections: From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical Translation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleitas Martínez, O.; Cardoso, M.H.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Franco, O.L. Recent Advances in Anti-Virulence Therapeutic Strategies with a Focus on Dismantling Bacterial Membrane Microdomains, Toxin Neutralization, Quorum-Sensing Interference and Biofilm Inhibition. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyemo, R.O.; Famuyide, I.M.; Dzoyem, J.P.; Joy, L.M. Anti-Biofilm, Antibacterial, and Anti-Quorum Sensing Activities of Selected South African Plants Traditionally Used to Treat Diarrhoea. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 1307801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edziri, H.; Jaziri, R.; Chehab, H.; Verschaeve, L.; Flamini, G.; Boujnah, D.; Hammami, M.; Aouni, M.; Mastouri, M. A comparative study on chemical composition, antibiofilm and biological activities of leaves extracts of four Tunisian olive cultivars. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almanaa, T.N.; Alharbi, N.S.; Ramachandran, G.; Chelliah, C.K.; Rajivgandhi, G.; Manoharan, N.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Khaled, J.M.; Alanzi, K.F. Anti-biofilm effect of Nerium oleander essential oils against biofilm forming Pseudomonas aeruginosa on urinary tract infections. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Boby, S.; Muyyarikkandy, M.S. Phytochemicals: A Promising Strategy to Combat Biofilm-Associated Antimicrobial Resistance. In Exploring Bacterial Biofilms; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Fu, T.; Xie, J. Polyphosphate deficiency affects the sliding motility and biofilm formation of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Curr. Microbiol. 2011, 63, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant Extracts (Acetone) | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/g Extract) | Total Tannin Content (mg GAE/g Extract) | Total Flavonoid Content (mg QE/g Extract) | Total Flavonols Content (mg QE/g Extract) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ap | 6.09 ± 0.26 b | 0.20 ± 0.004 b | 1.72 ± 0.04 b | 5.62 ± 0.71 b |

| Ch | 24.59 ± 0.08 f | 1.91 ± 0.02 f | 10.09 ± 0.19 g | 14.39 ± 0.67 d |

| Lo | 12.05 ± 0.79 d | 0.41 ± 0.004 d | 7.23 ± 0.39 f | 23.71 ± 0.53 e |

| No | 6.04 ± 0.23 b | 0.30 ± 0.005 c | 2.57 ± 0.07 c | 1.31 ± 0.89 a |

| Pm | 11.09 ± 0.16 c | 0.34 ± 0.013 c | 5.18 ± 0.06 e | 22.97 ± 0.97 e |

| Oa | 11.41 ± 0.03 c,d | 0.49 ± 0.27 e | 3.43 ± 0.06 d | 26.99 ± 0.90 f |

| Sm | 20.24 ± 0.07 e | 1.07 ± 0.008 f | 12.56 ± 0.10 h | 27.65 ± 0.80 f |

| Te | 3.09 ± 0.14 a | 0.11 ± 0.005 a | 1.23 ± 0.06 a | 43.19 ± 0.24 g |

| Tc | 28.94 ± 0.53 g | 2.19 ± 0.009 g | 30.61 ± 0.09 i | 10.34 ± 0.48 c |

| Tr | 5.90 ± 0.12 b | 0.21 ± 0.003 b | 2.78 ± 0.09 c | 1.18 ± 0.44 a |

| Samples | DPPH Scavenging Activity | r2 | Ferric Reducing Power | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ap | 789.83 | 0.99 | 1296.67 | 0.99 |

| Ch | 50.21 | 0.99 | 63.15 | 0.99 |

| Lo | 652.24 | 0.96 | 757 | 0.99 |

| No | 490.79 | 0.99 | 848.2 | 0.97 |

| Pm | 464.25 | 0.99 | 793.8 | 0.98 |

| Oa | 332.35 | 0.96 | 773.4 | 0.98 |

| Sm | 247.75 | 0.98 | 367.3 | 0.98 |

| Te | 1456 | 0.97 | 2058 | 0.98 |

| Tc | 38.73 | 0.99 | 195.6 | 0.99 |

| Tr | 466.90 | 0.99 | 654.33 | 0.99 |

| Ascorbic acid | 33.31 | 0.97 | 48.70 | 0.99 |

| Plants | H | D | A | M | W | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC | TA | MIC | MBC | TA | MIC | MBC | TA | MIC | MBC | TA | MIC | MBC | TA | |

| Ap | 2.5 | >2.5 | 16.80 | 1.04 | >2.5 | 52.88 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 29.60 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 92.80 | 2.5 | >2.5 | 32.00 |

| Ch | 0.63 | >2.5 | 123.81 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 130.16 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 138.10 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 160.80 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 280.95 |

| Lo | 1.25 | >2.5 | 36.80 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 158.73 | 0.52 | >2.5 | 130.77 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 85.60 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 65.60 |

| No | 2.5 | >2.5 | 11.20 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 60.00 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 47.20 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 79.20 | 0.16 | >2.5 | 518.75 |

| Pm | 2.5 | >2.5 | 20.00 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 185.71 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 109.52 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 160.80 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 133.60 |

| Oa | 2.5 | >2.5 | 4.00 | 2.5 | >2.5 | 20.40 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 55.56 | 0.31 | >2.5 | 367.74 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 188.89 |

| Sm | 2.5 | >2.5 | 74.00 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 215.87 | 0.16 | >2.5 | 112.50 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 247.60 | 0.16 | >2.5 | 806.25 |

| Te | 2.5 | >2.5 | 21.20 | 0.83 | >2.5 | 155.42 | 2.5 | >2.5 | 46.40 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 94.40 | >2.5 | >2.5 | - |

| Tc | 2.5 | >2.5 | 15.20 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 63.20 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 109.52 | 1.25 | >2.5 | 66.40 | 0.63 | >2.5 | 150.79 |

| Tr | 2.5 | >2.5 | 30.00 | 0.16 | >2.5 | 187.50 | 0.83 | >2.5 | 112.05 | 2.5 | >2.5 | 145.60 | 2.5 | >2.5 | 24.00 |

| Rif | 0.16 | ||||||||||||||

| Combination | FIC (A) | FIC (B) | FIC Index (ΣFIC) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ap + Ch | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | Indifferent |

| Ap + Lo | 0.50 | 1.21 | 1.72 | Indifferent |

| Ap + No | 1.66 | 1.66 | 3.33 | Indifferent |

| Ap + Pm | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | Indifferent |

| Ap + Oa | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | Indifferent |

| Ap + Sm | 0.34 | 2.63 | 2.96 | Indifferent |

| Ap + Te | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.76 | Additive |

| Ap + Tc | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | Indifferent |

| Ap + Tr | 0.50 | 0.76 | 1.26 | Indifferent |

| Ch + Lo | 1.00 | 1.21 | 2.21 | Indifferent |

| Ch + No | 1.98 | 1.00 | 2.98 | Indifferent |

| Ch + Pm | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | Indifferent |

| Ch + Oa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | Indifferent |

| Ch + Sm | 0.49 | 1.94 | 2.43 | Indifferent |

| Ch + Te | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.25 | Indifferent |

| Ch + Tc | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | Indifferent |

| Ch + Tr | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1.76 | Indifferent |

| Lo + No | 1.21 | 0.50 | 1.72 | Indifferent |

| Lo + Pm | 2.40 | 1.98 | 4.39 | Antagonistic |

| Lo + Oa | 1.21 | 1.00 | 2.21 | Indifferent |

| Lo + Sm | 0.81 | 2.63 | 3.43 | Indifferent |

| Lo + Te | 2.40 | 0.50 | 2.90 | Indifferent |

| Lo + Tc | 1.21 | 1.00 | 2.21 | Indifferent |

| Lo + Tr | 1.19 | 0.75 | 1.94 | Indifferent |

| No + Pm | 1.00 | 1.98 | 2.98 | Indifferent |

| No + Oa | 1.00 | 1.98 | 2.98 | Indifferent |

| No + Sm | 0.25 | 1.94 | 2.19 | Indifferent |

| No + Te | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.76 | Additive |

| No + Tc | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | Indifferent |

| No + Tr | 0.50 | 0.76 | 1.26 | Indifferent |

| Pm + Oa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | Indifferent |

| Pm + Sm | 0.49 | 1.94 | 2.43 | Indifferent |

| Pm + Te | 1.32 | 0.33 | 1.65 | Indifferent |

| Pm + Tc | 1.98 | 1.98 | 3.97 | Indifferent |

| Pm + Tr | 1.98 | 1.51 | 3.49 | Indifferent |

| Oa + Sm | 0.49 | 1.94 | 2.43 | Indifferent |

| Oa + Te | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.25 | Indifferent |

| Oa + Tc | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | Indifferent |

| Oa + Tr | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1.76 | Indifferent |

| Sm + Te | 3.94 | 0.25 | 4.19 | Antagonistic |

| Sm + Tc | 3.94 | 1.00 | 4.94 | Antagonistic |

| Sm + Tr | 3.94 | 0.76 | 4.70 | Antagonistic |

| Te + Tc | 0.25 | 1.00 | 1.25 | Indifferent |

| Te + Tr | 1.00 | 3.01 | 4.01 | Antagonistic |

| Tc + Tr | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1.76 | Indifferent |

| Combinational effects with the positive control | ||||

| Ap + R | 0.50 | 3.94 | 4.44 | Antagonistic |

| Ch + R | 0.25 | 1.00 | 1.25 | Indifferent |

| Lo + R | 1.21 | 3.94 | 5.15 | Antagonistic |

| No + R | 0.13 | 1.00 | 1.13 | Indifferent |

| Pm + R | 1.00 | 3.94 | 4.94 | Antagonistic |

| Oa + R | 1.00 | 3.94 | 4.94 | Antagonistic |

| Sm + R | 1.94 | 1.94 | 3.88 | Indifferent |

| Te + R | 0.33 | 5.19 | 5.52 | Antagonistic |

| Tc + R | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.94 | Additive |

| Tr + R | 1.51 | 7.81 | 9.32 | Antagonistic |

| Plants | MIC | ½ MIC |

|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin | 100 ± 0.00 | 100 ± 0.00 |

| Leonotis ocymifolia | 56.43 ± 1.01 | 41 ± 2.63 |

| Nerium oleander | 100 ± 0.00 | 70.71 ± 1.01 |

| Olea europaea subsp africana | 70 ± 2.02 | 12.57 ± 2.42 |

| Senecio macroglossus | 41.79 ± 1.52 | 56 ± 1.62 |

| Tetradenia raparia | 27.29 ± 1.82 | 99.29 ± 1.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mashilo, M.L.; Matotoka, M.M.; Masoko, P. Antimycobacterial Mechanisms and Anti-Virulence Activities of Polyphenolic-Rich South African Medicinal Plants Against Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010239

Mashilo ML, Matotoka MM, Masoko P. Antimycobacterial Mechanisms and Anti-Virulence Activities of Polyphenolic-Rich South African Medicinal Plants Against Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):239. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010239

Chicago/Turabian StyleMashilo, Matsilane L., Mashilo M. Matotoka, and Peter Masoko. 2026. "Antimycobacterial Mechanisms and Anti-Virulence Activities of Polyphenolic-Rich South African Medicinal Plants Against Mycobacterium smegmatis" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010239

APA StyleMashilo, M. L., Matotoka, M. M., & Masoko, P. (2026). Antimycobacterial Mechanisms and Anti-Virulence Activities of Polyphenolic-Rich South African Medicinal Plants Against Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microorganisms, 14(1), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010239