Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Donor Screening: Is Dientamoeba fragilis a Valid Criterion for Donor Exclusion? A Longitudinal Study of a Swiss Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Participants

2.2.1. Patients–rCDI

2.2.2. Donors

2.3. Native Stool Collection, D. fragilis Detection

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. RT-PCR Detection of D. fragilis in Stools from Donors and FMT Recipients

3.2. Efficacy at 8 Weeks According to D. fragilis Positivity of the Donors

3.3. AE and SAE at 15 Days and 8 Weeks Post FMT

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEs | Adverse Events |

| AGA | American Gastroenterology Association |

| B. hominis | Blastocystis hominis |

| CDI | Clostridioides difficile infection |

| CHUV | Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois |

| Ct | Cycle Threshold |

| D. fragilis | Dientamoeba fragilis |

| EDQM | European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare |

| ESCMID | European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases |

| FMT | Fecal Microbiota Transplantation |

| GvHD | Graft-versus-Host Disease |

| IBS | Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

| ICH E2A | International Conference on Harmonisation, article E2A (Clinical Safety) |

| ID | Identifier |

| rCDI | Recurrent CDI |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture software |

| RT-PCR | Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SAEs | Serious Adverse Events |

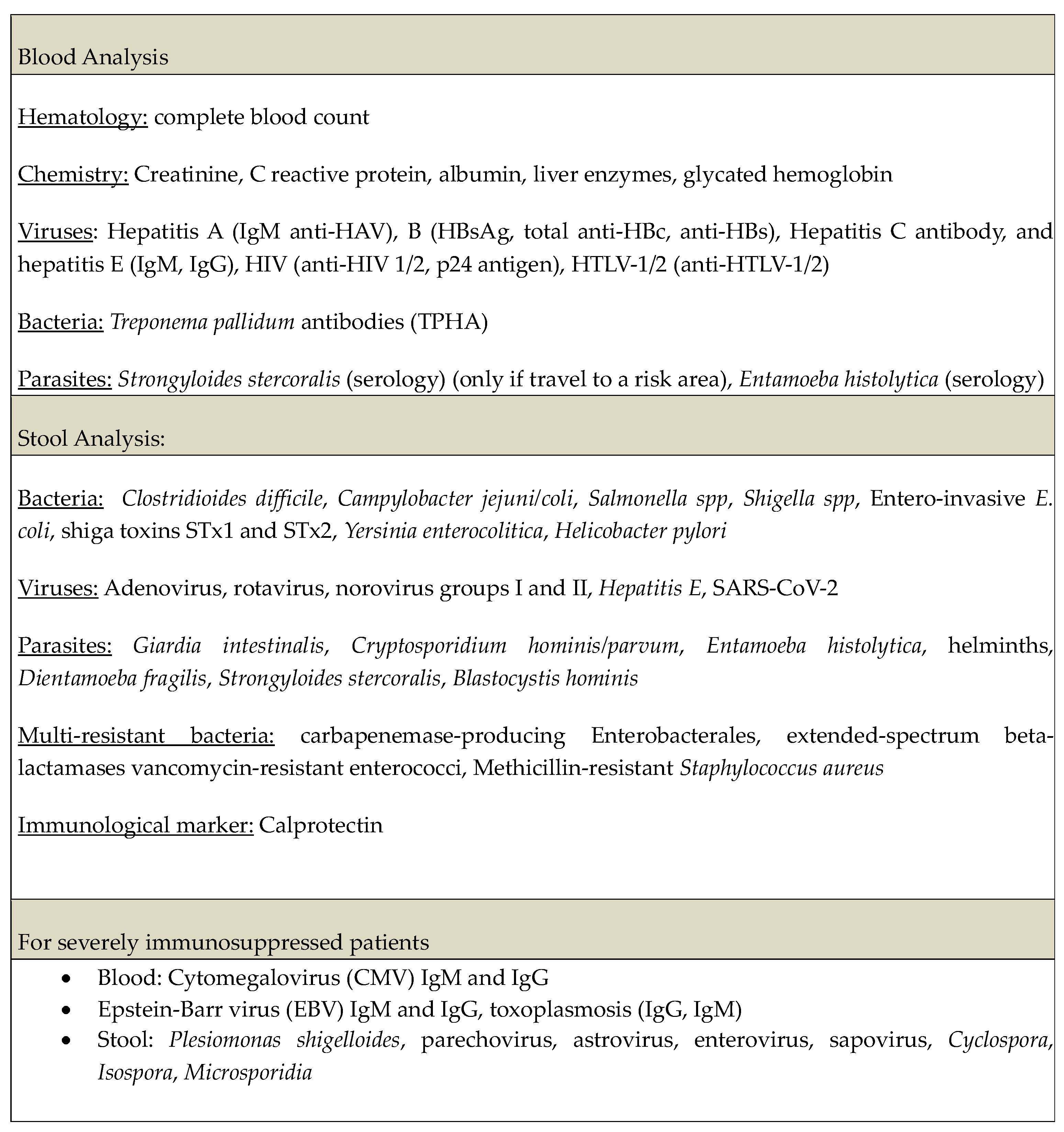

Appendix A

Biological Screening for Donor Selection in Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for the Treatment of Clostridioides difficile Infection

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. FMT Production

Appendix B.2. Diagnosis of D. fragilis-RT-PCR

Appendix B.3. Metagenomics

References

- van Prehn, J.; Reigadas, E.; Vogelzang, E.H.; Bouza, E.; Hristea, A.; Guery, B.; Krutova, M.; Norén, T.; Allerberger, F.; Coia, J.E.; et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: 2021 update on the treatment guidance document for Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, S1–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peery, A.F.; Kelly, C.R.; Kao, D.; Vaughn, B.P.; Lebwohl, B.; Singh, S.; Imdad, A.; Altayar, O. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on Fecal Microbiota–Based Therapies for Select Gastrointestinal Diseases. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 409–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.C.; Gerding, D.N.; Johnson, S.; Bakken, J.S.; Carroll, K.C.; Coffin, S.E.; Dubberke, E.R.; Garey, K.W.; Gould, C.V.; Kelly, C.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, e1–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianiro, G.; Maida, M.; Burisch, J.; Simonelli, C.; Hold, G.; Ventimiglia, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G. Efficacy of different faecal microbiota transplantation protocols for Clostridium difficile infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, M.N.; Widlak, M.; Bhala, N.; Moore, D.; Price, M.; Sharma, N.; Iqbal, T.H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent and refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G.; Kelly, C.R.; Mullish, B.H.; Allegretti, J.R.; Kassam, Z.; Putignani, L.; Fischer, M.; Keller, J.J.; Costello, S.P.; et al. International consensus conference on stool banking for faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 2019, 68, 2111–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terveer, E.M.; Vendrik, K.E.; E Ooijevaar, R.; van Lingen, E.; Boeije-Koppenol, E.; van Nood, E.; Goorhuis, A.; Bauer, M.P.; van Beurden, Y.H.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.; et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridioides difficile infection: Four years’ experience of the Netherlands Donor Feces Bank. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2020, 8, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénard, M.V.; de Bruijn, C.M.A.; Fenneman, A.C.; Wortelboer, K.; Zeevenhoven, J.; Rethans, B.; Herrema, H.J.; van Gool, T.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Benninga, M.A.; et al. Challenges and costs of donor screening for fecal microbiota transplantations. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, L.M.; Munasinghe, V.S.; Vella, N.G.F.; Ellis, J.T.; Stark, D. Observations on the transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis and the cyst life cycle stage. Parasitology 2024, 151, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciò, S.M. Molecular epidemiology of Dientamoeba fragilis. Acta Trop. 2018, 184, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shasha, D.; Grupel, D.; Treigerman, O.; Prajgrod, G.; Paran, Y.; Hacham, D.; Ben-Ami, R.; Albukrek, D.; Zacay, G. The clinical significance of Dientamoeba fragilis and Blastocystis in human stool-retrospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terveer, E.M.; van Gool, T.; E Ooijevaar, R.; Sanders, I.M.J.G.; Boeije-Koppenol, E.; Keller, J.J.; Bart, A.; Kuijper, E.J.; Netherlands Donor Feces Bank (NDFB) Study Group; Vendrik, K.E.W.; et al. Human Transmission of Blastocystis by Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Without Development of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. ICH E2A Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting-Scientific Guideline; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-e2a-clinical-safety-data-management-definitions-standards-expedited-reporting-scientific-guideline (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- American Gastroenterological Association. Fecal Microbiota Transplant National Registry; American Gastroenterological Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2017. Available online: https://cdn.clinicaltrials.gov/large-docs/55/NCT03325855/Prot_000.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Stark, D.; Garcia, L.S.; Barratt, J.L.N.; Phillips, O.; Roberts, T.; Marriott, D.; Harkness, J.; Ellis, J.T. Description of Dientamoeba fragilis cyst and precystic forms from human samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 2680–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensvold, C.R.; Tomiak, J.; Seyoum, Y.; Nielsen, H.V.; van der Giezen, M. Letter to the Editor: Comment to ‘Assessment of Dientamoeba fragilis interhuman transmission by faecal microbiota transplantation’ by Moreno-Sabater et al. (2025). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2025, 66, 107541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Sabater, A.; Sintes, R.; Truong, S.; Lemoine, K.; Camou, O.; Kapel, N.; Magne, D.; Joly, A.-C.; Quelven-Bertin, I.; Alric, L.; et al. Assessment of Dientamoeba fragilis interhuman transmission by fecal microbiota transplantation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2025, 66, 107504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurych, J.; Vodolanova, L.; Vejmelka, J.; Drevinek, P.; Kohout, P.; Cinek, O.; Nohynkova, E. Freezing of faeces dramatically decreases the viability of Blastocystis sp. and Dientamoeba fragilis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 34, 242–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röser, D.; Simonsen, J.; Stensvold, C.R.; Olsen, K.E.P.; Bytzer, P.; Nielsen, H.V.; Mølbak, K. Metronidazole therapy for treating dientamoebiasis in children is not associated with better clinical outcomes: A randomized, double-blinded and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1692–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamini, G.T.; Charpentier, E.; Guemas, E.; Chauvin, P.; Fillaux, J.; Valentin, A.; Cassaing, S.; Ménard, S.; Berry, A.; Iriart, X. No evidence of pathogenicity of Dientamoeba fragilis following detection in stools: A case-control study. Aucune preuve de la pathogénicité de Dientamoeba fragilis détecté dans les selles: Une étude cas-témoins. Parasite 2024, 31, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, M.D.; Schuurs, T.A.; Vermeer, M.; Ruijs, G.J.; van der Zanden, A.G.M.; Weel, J.F.; van Coppenraet, L.E.B. Distribution and relevance of Dientamoeba fragilis and Blastocystis species in gastroenteritis: Results from a case-control study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kalleveen, M.W.; Budding, A.E.; Benninga, M.A.; Savelkoul, P.H.; van Gool, T.; van Maldeghem, I.; Dorigo-Zetsma, J.W.; Bart, A.; Plötz, F.B.; de Meij, T.G. Intestinal Microbiota in Children With Symptomatic Dientamoeba fragilis Infection: A Case-control Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mızrak, M.; Sarzhanov, F.; Demirel, F.; Dinç, B.; Filik, L.; Dogruman-Al, F. Detection of Blastocystis sp. and Dientamoeba fragilis using conventional and molecular methods in patients with celiac disease. Parasitol. Int. 2024, 101, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röser, D.; Simonsen, J.; Nielsen, H.V.; Stensvold, C.R.; Mølbak, K. Dientamoeba fragilis in Denmark: Epidemiological experience derived from four years of routine real-time PCR. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, J.L.; Cao, M.; Stark, D.J.; Ellis, J.T. The Transcriptome Sequence of Dientamoeba fragilis Offers New Biological Insights on its Metabolism, Kinome, Degradome and Potential Mechanisms of Pathogenicity. Protist 2015, 166, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | D. fragilis-Negative Donor Stool a | D. fragilis-Positive Donor Stool a | p-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 73 (44, 79) | 57 (52, 71) | 0.2 |

| Sex | >0.9 | ||

| Male | 73% (22/30) | 74% (17/23) | |

| Female | 27% (8/30) | 26% (6/23) | |

| Severe CDI, yes | 50% (15/30) | 48% (11/23) | 0.9 |

| Immunosuppression, yes | 27% (8/30) | 43% (10/23) | 0.2 |

| Severe immunosuppression, yes | 6.7% (2/30) | 8.7% (2/23) | >0.9 |

| Route of FMT administration | 0.05 | ||

| Capsules | 70% (21/30) | 43% (10/23) | |

| Colonoscopy | 30% (9/30) | 48% (11/23) | |

| Jejunostomy | 0% (0/30) | 8.7% (2/23) | |

| FMT efficacy | 0.12 | ||

| Cured | 87% (26/30) | 100% (23/23) | |

| Recurrence | 13% (4/30) | 0% (0/23) |

| Donors | Recipients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor ID | D. fragilis Ct Value | Storage Duration Pre-FMT a, Days | Patient ID | D. fragilis Status Pre-FMT | D. fragilis Status D15 Post-FMT | Ct Value D15 | D. fragilis Status W8 Post-FMT | Ct Value W8 |

| DL01 | 23 | 237 | RL01 | Pos | Neg | n/a | Pos | 30.6 |

| DL01 | 23 | 222 | RL02 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 217 | RL03 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 168 | RL05 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 204 | RL05 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 162 | RL07 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 203 | RL08 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 35 | RL10 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 27.2 | 239 | RL35 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 257 | RL36 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 384 | RL38 | Neg | Pos | 25 | Pos | 21 |

| DL01 | 19.3 | 370 | RL42 | Neg | Pos | 21 | Pos | 21 |

| DL01 | 19.3 | 377 | RL45 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL01 | 23 | 729 | RL47 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL02 | 23.13 | 202 | RL04 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL02 | 23.13 | 246 | RL37 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL02 | 23.13 | 379 | RL46 | Neg | Pos | 27 | Pos | 26 |

| DL03 | 32.5 | 260 | RL06 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL03 | 31.6 | 106 | RL27 | Neg | Pos | 33.6 | Pos | 34.5 |

| DL03 | 31.6 | 462 | RL43 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL03 | 31.6 | 497 | RL44 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL05 | 36.1 | 714 | RL11 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| DL05 | 30.5 | 702 | RL11 | Neg | Neg | n/a | Neg | n/a |

| Gastrointestinal Adverse Events | D. fragilis-Negative Donor Stool a | D. fragilis-Positive Donor Stool a | p-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| GI AE undif. | 73.3% (22/30) | 60.1% (14/23) | 0.3 |

| Constipation | 7% (2/30) | 8.7% (2/23) | >0.9 |

| Diarrhea | 16.7% (5/30) | 4.3% (1/23) | 0.5 |

| Nausea | 7% (2/30) | 21.7% (5/23) | 0.2 |

| Abdominal pain | 33.3% (10/30) | 39.1% (9/23) | 0.6 |

| Bloating | 10% (3/30) | 21.7% (5/23) | 0.3 |

| Abdominal disconfort | 3.3% (1/30) | 8.7% (2/23) | 0.6 |

| Altered bowel habits | 26.7% (8/30) | 13% (3/23) | 0.12 |

| Other | 10% (3/30) | 4.3% (1/23) | >0.9 |

| SAE | 20% (6/30) | 17.4% (4/23) | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moser, K.; Ballif, A.; Pillonel, T.; Concu, M.; Montenegro-Borbolla, E.; Nickel, B.; Stampfli, C.; Ruf, M.-T.; Audry, M.; Kapel, N.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Donor Screening: Is Dientamoeba fragilis a Valid Criterion for Donor Exclusion? A Longitudinal Study of a Swiss Cohort. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010217

Moser K, Ballif A, Pillonel T, Concu M, Montenegro-Borbolla E, Nickel B, Stampfli C, Ruf M-T, Audry M, Kapel N, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Donor Screening: Is Dientamoeba fragilis a Valid Criterion for Donor Exclusion? A Longitudinal Study of a Swiss Cohort. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):217. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010217

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoser, Keyvan, Aurélie Ballif, Trestan Pillonel, Maura Concu, Elena Montenegro-Borbolla, Beatrice Nickel, Camille Stampfli, Marie-Therese Ruf, Maxime Audry, Nathalie Kapel, and et al. 2026. "Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Donor Screening: Is Dientamoeba fragilis a Valid Criterion for Donor Exclusion? A Longitudinal Study of a Swiss Cohort" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010217

APA StyleMoser, K., Ballif, A., Pillonel, T., Concu, M., Montenegro-Borbolla, E., Nickel, B., Stampfli, C., Ruf, M.-T., Audry, M., Kapel, N., Gerber, S., Jacot, D., Bertelli, C., & Galpérine, T. (2026). Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Donor Screening: Is Dientamoeba fragilis a Valid Criterion for Donor Exclusion? A Longitudinal Study of a Swiss Cohort. Microorganisms, 14(1), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010217