Quantitative Assessment of Total Aerobic Viable Counts in Apitoxin-, Royal-Jelly-, Propolis-, Honey-, and Bee-Pollen-Based Products Through an Automated Growth-Based System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Automated Growth-Based System

2.3. Inoculum Standardization

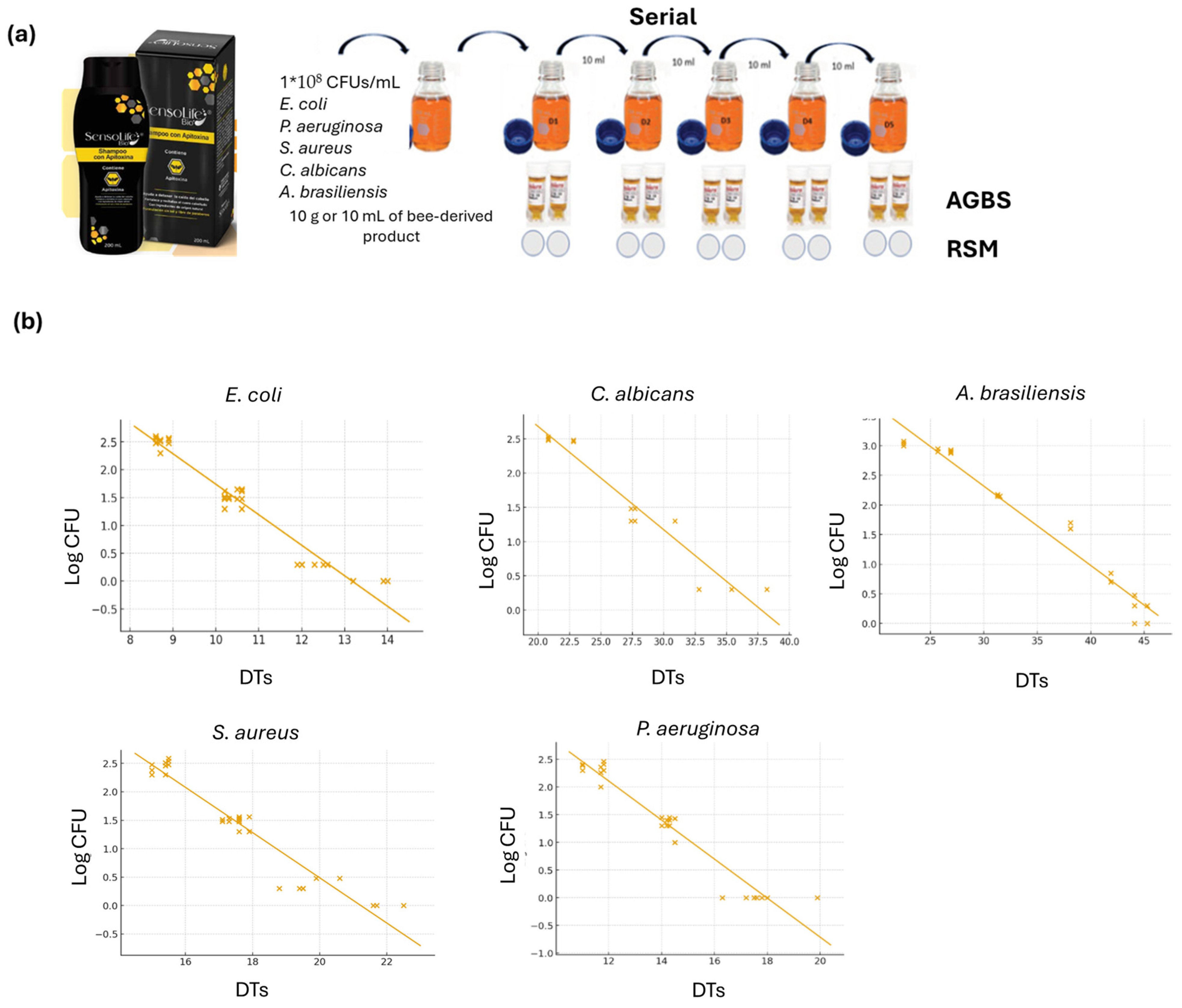

2.4. Suitability of the Method

2.5. Calibration Curve

2.6. Linearity and Equivalence of Results

2.7. Accuracy

2.8. Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantification

2.9. Precision

3. Results

3.1. Suitability of the Method (Antimicrobial Neutralization)

3.2. Linearity, Operative Range, and Equivalence of Results

3.3. Accuracy

3.4. Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantification

3.5. Intermediate Precision and Ruggedness

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kurek-Górecka, A.; Górecki, M.; Rzepecka-Stojko, A.; Balwierz, R.; Stojko, J. Bee Products in Dermatology and Skin Care. Antioxidants 2020, 25, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiecińska-Piróg, J.; Przekwas, J.; Majkut, M.; Skowron, K.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Biofilm Formation Reducing Properties of Manuka Honey and Propolis in Proteus mirabilis Rods Isolated from Chronic Wounds. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romário-Silva, D.; Alencar, S.; Bueno-Silva, B.; Orlandi Sardi, J.; Franchin, M.; Parolina de Carvalho, R.; Alves Ferreira, T.; Luiz Rosalen, P. Antimicrobial Activity of Honey against Oral Microorganisms: Current Reality, Methodological Challenges and Solutions. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rim, W.; Jacinthe, F.; Mohamad, R.; Dany, E.-O.; Jean, M.; Ziad, F. Bee Venom: Overview of Main Compounds and Bioactivities for Therapeutic Interests. Molecules 2019, 24, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aida, E.; Shaden, K.; Mohamed, E.; Syed, M.; Aamer, S.; Alfi, K.; Haroon, T.; Xiaobo, Z.; Yahya, N.; Arshad, M.; et al. Cosmetic Applications of Bee Venom. Toxins 2021, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collazo, N.; Carpena, M.; Nuñez, E.-B.; Otero, S.-G.; Prieto, M.-A. Health Promoting Properties of Bee Royal Jelly: Food of the Queens. Nutrients 2021, 13, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soukaïna, E.-G.; Alexandra, M.-M.; Smail, A.; Badiaâ, L.; Maria, G.-M.; Maria, C.-M.; Figueiredo, C.-A. Chemical Characterization and Biological Properties of Royal Jelly Samples From the Mediterranean Area. Nat. Product. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20908080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oršolić, N.; Jembrek, M.J. Royal Jelly: Biological Action and Health Benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocot, J.; Kiełczykowska, M.; Luchowska-Kocot, D.; Kurzepa, J.; Musik, I. Antioxidant Potential of Propolis, Bee Pollen, and Royal Jelly: Possible Medical Application. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7074209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiroshi, K.; Amira, M.-A. Royal Jelly and Its Components Promote Healthy Aging and Longevity: From Animal Models to Humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippo, F.; Giovanni, C.; Simone, M.; Antonio, F. Royal Jelly: An ancient remedy with remarkable antibacterial properties. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 192, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanshan, L.; Lingchen, T.; Xinyu, Y.; Huoqing, Z.; Jianping, W.; Fuliang, H. Royal Jelly Proteins and Their Derived Peptides: Preparation, Properties, and Biological Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 14415–14427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, H.-A.; Beltran, A.-U.; Celeita, S.-P.; Fonseca, J.-C. Performance equivalence and validation of a rapid microbiological method for detection and quantification of yeast and mold in an antacid oral suspension. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2023, 77, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, H.-A.; Celeita, S.-P.; Fonseca, J.C. Validation of a rapid microbiological method for the detection and quantification of Burkholderia cepacia complex in an antacid oral suspension. J. AOAC Int. 2023, 5, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, H.-A.; Celeita, S.-P.; Fonseca, J.C. Efficacy of an automated growth-based system and plate count method on the detection of yeasts and molds in personal care products. J. AOAC Int. 2023, 6, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereault, M.; Alles, S.; Caballero, O.; Sarver, R.; McDougal, S.; Mozola, M.; Rice, J. Validation of the SolerisVR Direct Yeast and Mold Method for Semiquantitative Determination of Yeast and Mold in a Variety of Foods. J. AOAC Int. 2014, 97, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limberg, B.-J.; Johnstone, K.; Filloon, T.; Catrenich, C. Performance equivalence and validation of the soleris automated system for quantitative microbial content testing using pure suspension cultures. J. AOAC Int. 2016, 99, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozola, M.; Gray, L.-R.; Feldpausch, J.; Alles, S.; McDougal, S.; Montei, C. Validation of the Soleris® NF-TVC method for determination of total viable count in a variety of foods. J. AOAC Int. 2013, 96, 399–403. [Google Scholar]

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP). Validation of Alternative Microbiological Methods (Chapter-1223); United States Pharmacopeia (USP): Rockville, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP). Validation of Compendial Methods (Chapter-1225); United States Pharmacopeia (USP): Rockville, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- United State Pharmacopeia Convention 42. Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Microbial Enumeration Test; United States Pharmacopeia (USP): Rockville, MD, USA, 2021; Chapter 61; pp. 8363–8384. [Google Scholar]

| Bee-Made Products |

|---|

| 1. Anti-aging cream (SensoLife Bio®): Citric acid, butylated hydroxytoluene, phenoxyethanol, ethylhexyloxyphenol, solid pollen, royal jelly, and apitoxin. |

| 2. Hair treatment (SensoLife Bio®): Royal jelly, phenoxyethanol, ethylhexyloxyphenol, apitoxin, cetostearyl alcohol, and glycerin. |

| 3. Toothpaste (SensoLife Bio®): Propylene glycol, glycerin, polyethylene glycol, propolis, honey, and 70% non-crystallizable sorbitol. |

| Bee-Made Product | Microorganisms | Linear Regression | R2 | x2 Square Test (p ≤ 0.05) | Upper Range of Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apitoxin–royal-jelly-based anti-aging creams | S. aureus | y = −2.3189x + 20.952 | 0.9225 | p = 0.00 | 3.9 × 102 |

| E. coli | y = −1.7331x + 13.046 | 0.9485 | p = 0.00 | 4.0 × 102 | |

| P. aeruginosa | y = −2.6517x + 17.735 | 0.9343 | p = 0.00 | 2.9 × 102 | |

| C. albicans | y = −6.1878x + 37.049 | 0.9319 | p = 0.00 | 3.0 × 102 | |

| A. brasiliensis | y = −0.1605x + 7.5561 | 0.9692 | p = 0.00 | 3.5 × 103 | |

| Propolis–honey-based toothpaste | S. aureus | y = −2.7201x + 18.76 | 0.9136 | p = 0.00 | 2.8 × 102 |

| E. coli | y = −1.7514x + 11.9 | 0.9174 | p = 0.00 | 2.9 × 102 | |

| P. aeruginosa | y = −2.89x + 17.68 | 0.9106 | p = 0.00 | 3.0 × 102 | |

| C. albicans | y = −3.4748x + 25.611 | 0.9281 | p = 0.00 | 2.0 × 102 | |

| A. brasiliensis | y = −0.0771x + 4.2792 | 0.9421 | p = 0.00 | 4.0 × 102 | |

| Bee-pollen-, apitoxin-, and royal-jelly-based creams (capillary treatments) | S. aureus | y = −2.5676x + 20.618 | 0.9241 | p = 0.00 | 4.1 × 102 |

| E. coli | y = −1.8052x + 12.46 | 0.9166 | p = 0.00 | 5.0 × 102 | |

| P. aeruginosa | y = −2.5797x + 18.917 | 0.9204 | p = 0.00 | 6.0 × 102 | |

| C. albicans | y = −3.6917x + 28.444 | 0.9206 | p = 0.00 | 5.0 × 102 | |

| A. brasiliensis | y = −5.8226x + 41.169 | 0.9107 | p = 0.00 | 1.0 × 103 |

| Bee-Made Product | Strains Used to Build Calibration Curves | % Recovery | Goodness-of-Fit Tests | Coefficient of Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apitoxin–royal-jelly-based anti-aging creams | S. aureus | 81 | 1.0000 | 0.9500 |

| E. coli | 100 | 0.9940 | 0.9700 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 102 | 1.0000 | 0.9700 | |

| C. albicans | 75 | 0.9870 | 0.9700 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 100 | 1.0000 | 0.9692 | |

| Propolis–honey-based toothpaste | S. aureus | 103 | 1.0000 | 0.9600 |

| E. coli | 100 | 1.0000 | 0.9600 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 107 | 0.9920 | 0.9500 | |

| C. albicans | 86 | 0.9080 | 0.9600 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 118 | 0.9990 | 0.9700 | |

| Capillary treatments | S. aureus | 90 | 0.9980 | 0.9613 |

| E. coli | 100 | 0.9990 | 0.9574 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 89 | 1.0000 | 0.9594 | |

| C. albicans | 103 | 0.9990 | 0.9595 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 87 | 1.0000 | 0.9543 |

| Bee-Made Products | Strains Used to Build Calibration Curves | RSM, CFU/mL | AGBS, CFU/mL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOD | LOQ | SD | LOD | LOQ | SD | ||

| Apitoxin–royal-jelly-based anti-aging creams | S. aureus | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| E. coli | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 2 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| C. albicans | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 5 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 16 | 5 | |

| Propolis–honey-based toothpaste | S. aureus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| E. coli | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 2 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 2 | |

| C. albicans | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Bee-pollen-, apitoxin-, and royal-jelly-based cream (capillary treatments) | S. aureus | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 2 |

| E. coli | 3 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 22 | 4 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 3 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 3 | |

| C. albicans | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 4 | 13 | 4 | 8 | 24 | 8 | |

| Bee-Made Product | Strains Used to Build Calibration Curves | Mean DT | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation | Mean CFU | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apitoxin-royal jelly based anti-aging creams | S. aureus | 17.51 | 0.26 | 1.51 | 30.33 | 5.31 | 17.51 |

| E. coli | 10.4 | 0.18 | 1.73 | 33.17 | 8.66 | 26.12 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 19.97 | 3.22 | 16.15 | 21.67 | 6.34 | 29.27 | |

| C. albicans | 28.22 | 1.50 | 5.33 | 24.00 | 5.48 | 22.82 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 38.1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 45.00 | 7.94 | 17.63 | |

| Propolis-honey based toothpaste | S. aureus | 15.54 | 0.28 | 1.82 | 18.80 | 4.80 | 25.5 |

| E. coli | 9.53 | 0.21 | 2.25 | 24.83 | 5.13 | 20.6 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 13.33 | 0.68 | 5.15 | 27.83 | 5.98 | 21.4 | |

| C. albicans | 20.8 | 0.2 | 0.96 | 21.30 | 2.16 | 10.15 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 39.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 31.66 | 2.8 | 9.12 | |

| Bee pollen, apitoxin, royal jelly-based shampoo | S. aureus | 16.35 | 0.77 | 4.71 | 38.55 | 6.25 | 16.21 |

| E. coli | 9.40 | 0.23 | 2.48 | 49.67 | 6.08 | 12.24 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 14.22 | 0.41 | 2.92 | 56.13 | 6.69 | 11.91 | |

| C. albicans | 22.42 | 0.80 | 3.61 | 39.86 | 6.01 | 15.08 | |

| A. brasiliensis | 27.70 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 110 | 10.00 | 9.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Prada-Ramírez, H.A.; Gómez-Pliego, R.; Zardo, H.; Cely-Veloza, W.-F.; Coy-Barrera, E.; Palacio-Beltrán, R.; Peña-Romero, R.; Gonzalez-Alarcon, S.; Fonseca-Acevedo, J.C.; Montes-Tamara, J.P.; et al. Quantitative Assessment of Total Aerobic Viable Counts in Apitoxin-, Royal-Jelly-, Propolis-, Honey-, and Bee-Pollen-Based Products Through an Automated Growth-Based System. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010218

Prada-Ramírez HA, Gómez-Pliego R, Zardo H, Cely-Veloza W-F, Coy-Barrera E, Palacio-Beltrán R, Peña-Romero R, Gonzalez-Alarcon S, Fonseca-Acevedo JC, Montes-Tamara JP, et al. Quantitative Assessment of Total Aerobic Viable Counts in Apitoxin-, Royal-Jelly-, Propolis-, Honey-, and Bee-Pollen-Based Products Through an Automated Growth-Based System. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010218

Chicago/Turabian StylePrada-Ramírez, Harold A., Raquel Gómez-Pliego, Humberto Zardo, Willy-Fernando Cely-Veloza, Ericsson Coy-Barrera, Rodrigo Palacio-Beltrán, Romel Peña-Romero, Sandra Gonzalez-Alarcon, Juan Camilo Fonseca-Acevedo, Juan Pablo Montes-Tamara, and et al. 2026. "Quantitative Assessment of Total Aerobic Viable Counts in Apitoxin-, Royal-Jelly-, Propolis-, Honey-, and Bee-Pollen-Based Products Through an Automated Growth-Based System" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010218

APA StylePrada-Ramírez, H. A., Gómez-Pliego, R., Zardo, H., Cely-Veloza, W.-F., Coy-Barrera, E., Palacio-Beltrán, R., Peña-Romero, R., Gonzalez-Alarcon, S., Fonseca-Acevedo, J. C., Montes-Tamara, J. P., Nieto-Celis, L., Dallos-Acosta, R., Gonzalez, T., Díaz-Báez, D., & Lafaurie, G. I. (2026). Quantitative Assessment of Total Aerobic Viable Counts in Apitoxin-, Royal-Jelly-, Propolis-, Honey-, and Bee-Pollen-Based Products Through an Automated Growth-Based System. Microorganisms, 14(1), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010218