Saccharomyces cerevisiae Response to Magnetic Stress: Role of a Protein Corona in Stable Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Reagents

2.2. Synthesis of AgNP in the Presence of Magnetic Field

2.3. Characterization of Nanoparticles

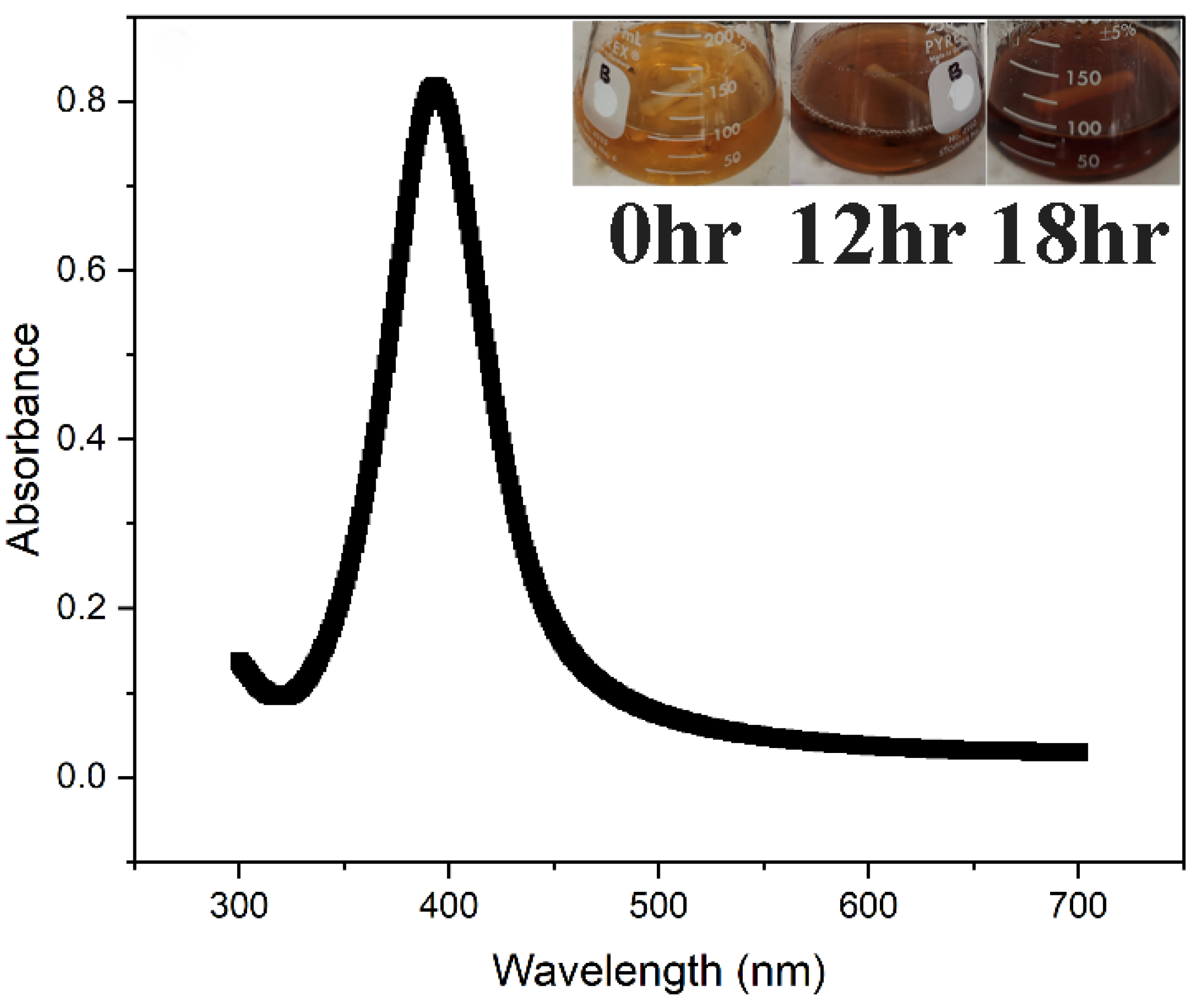

2.3.1. UV–Visible Absorbance Spectral Analysis

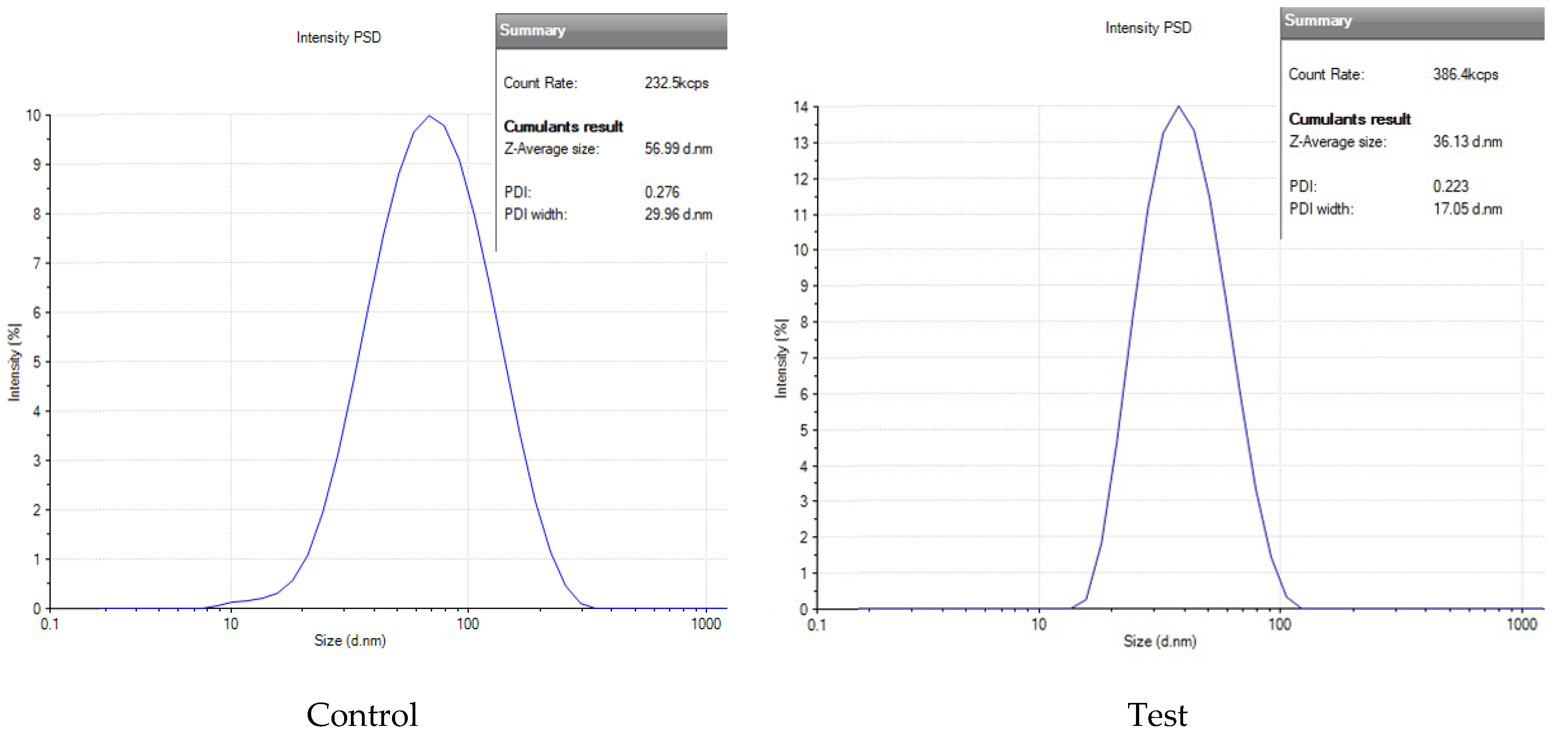

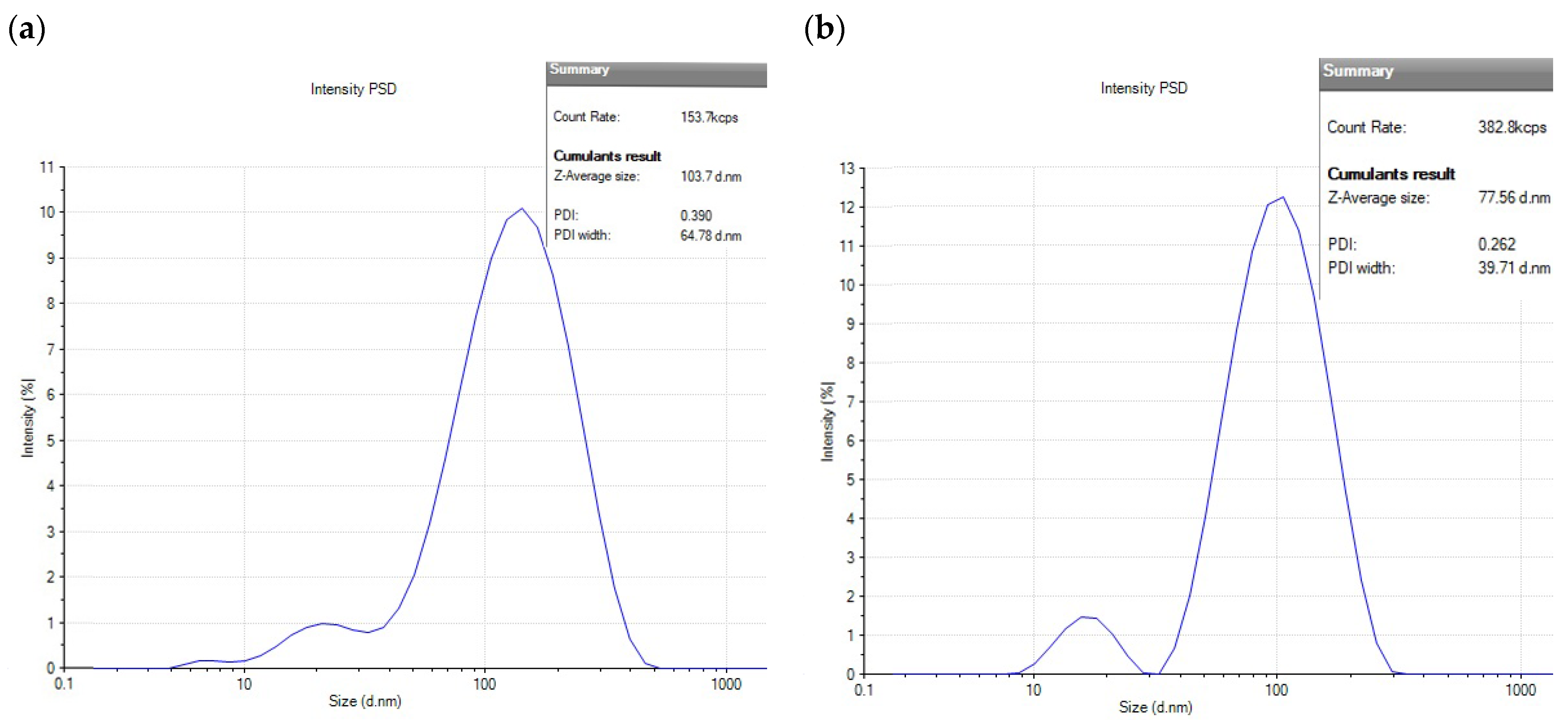

2.3.2. Dynamic Light Scattering

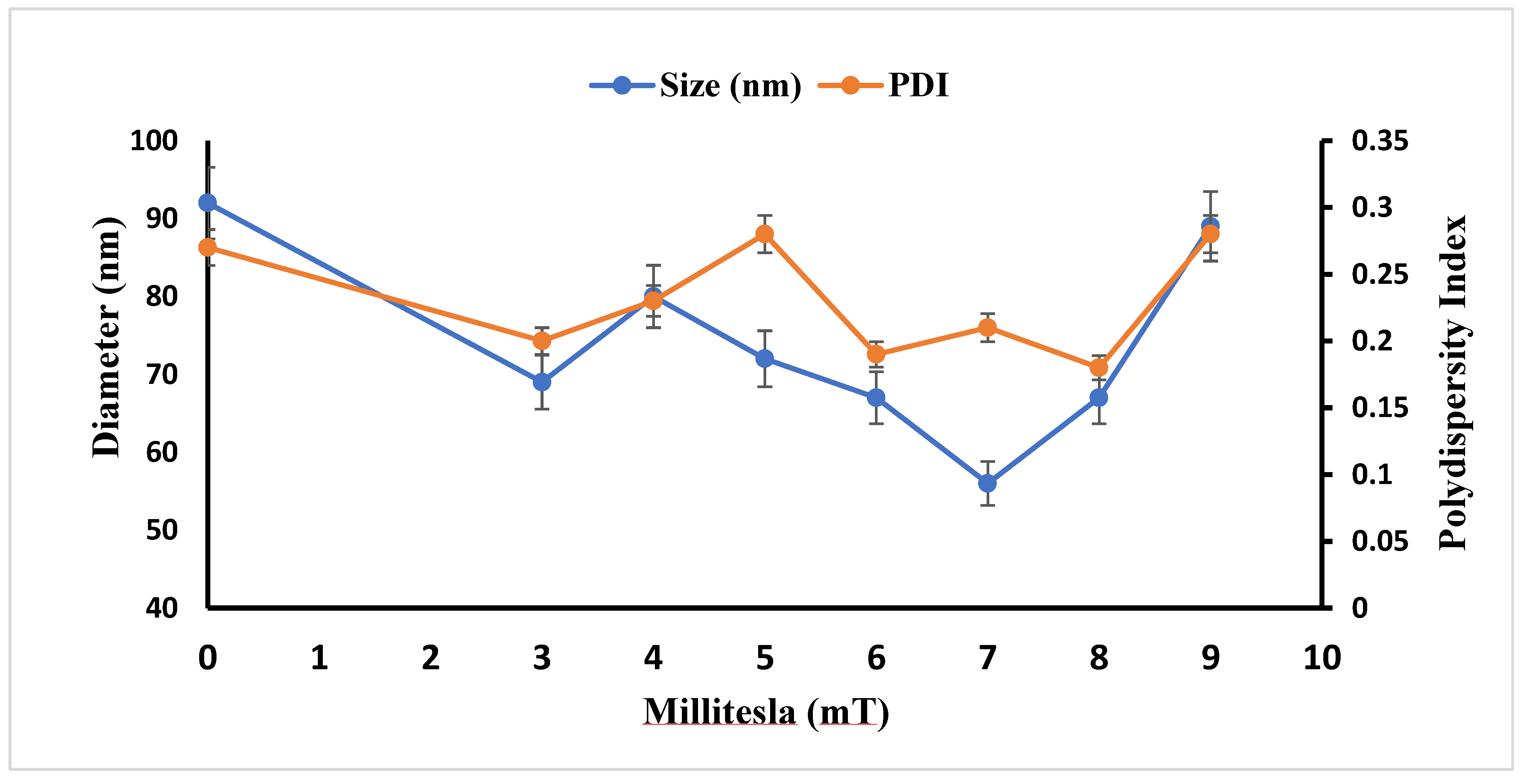

2.3.3. Stability Assessment of AgNPs: Hydrodynamic Size and PDI Analysis

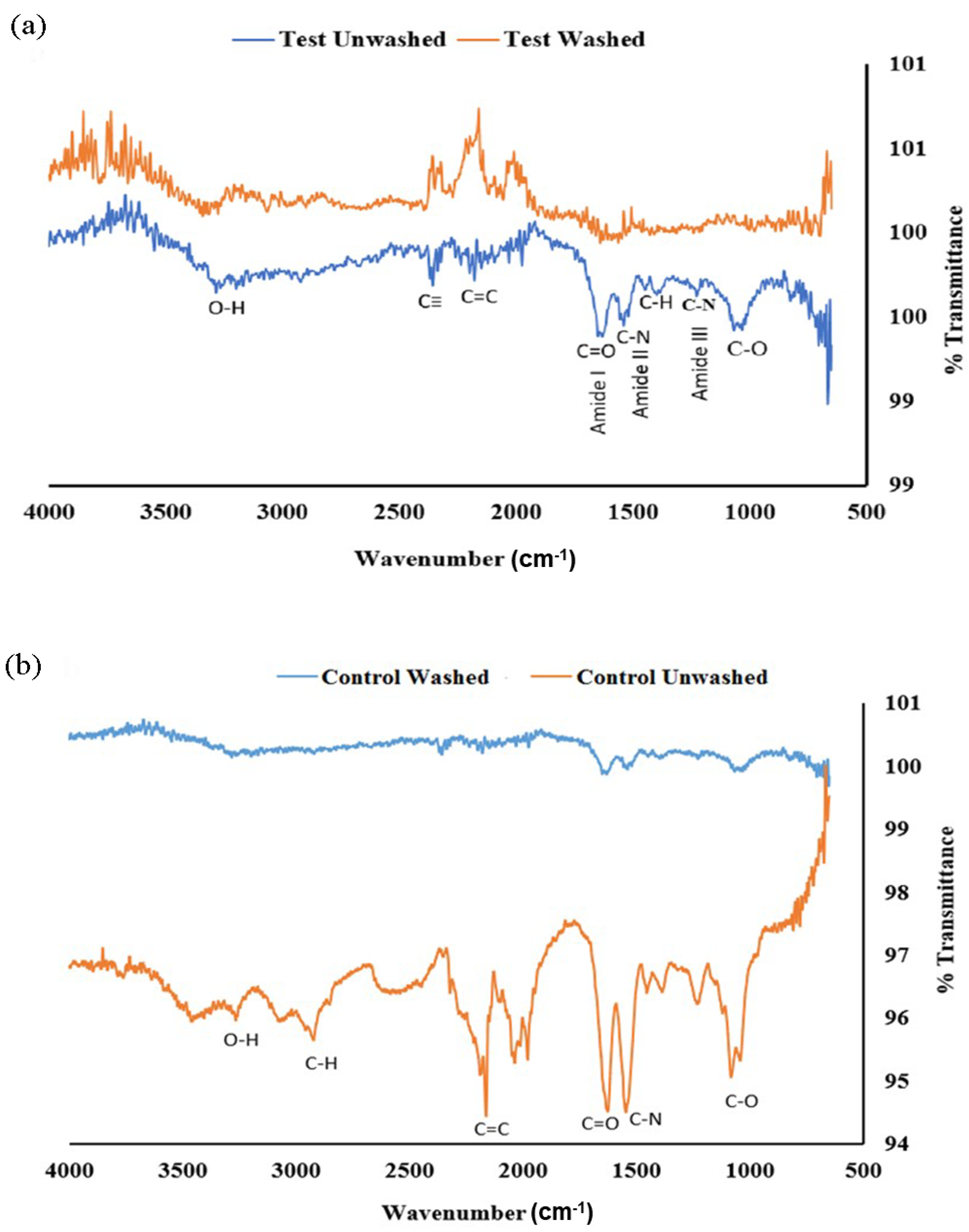

2.3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

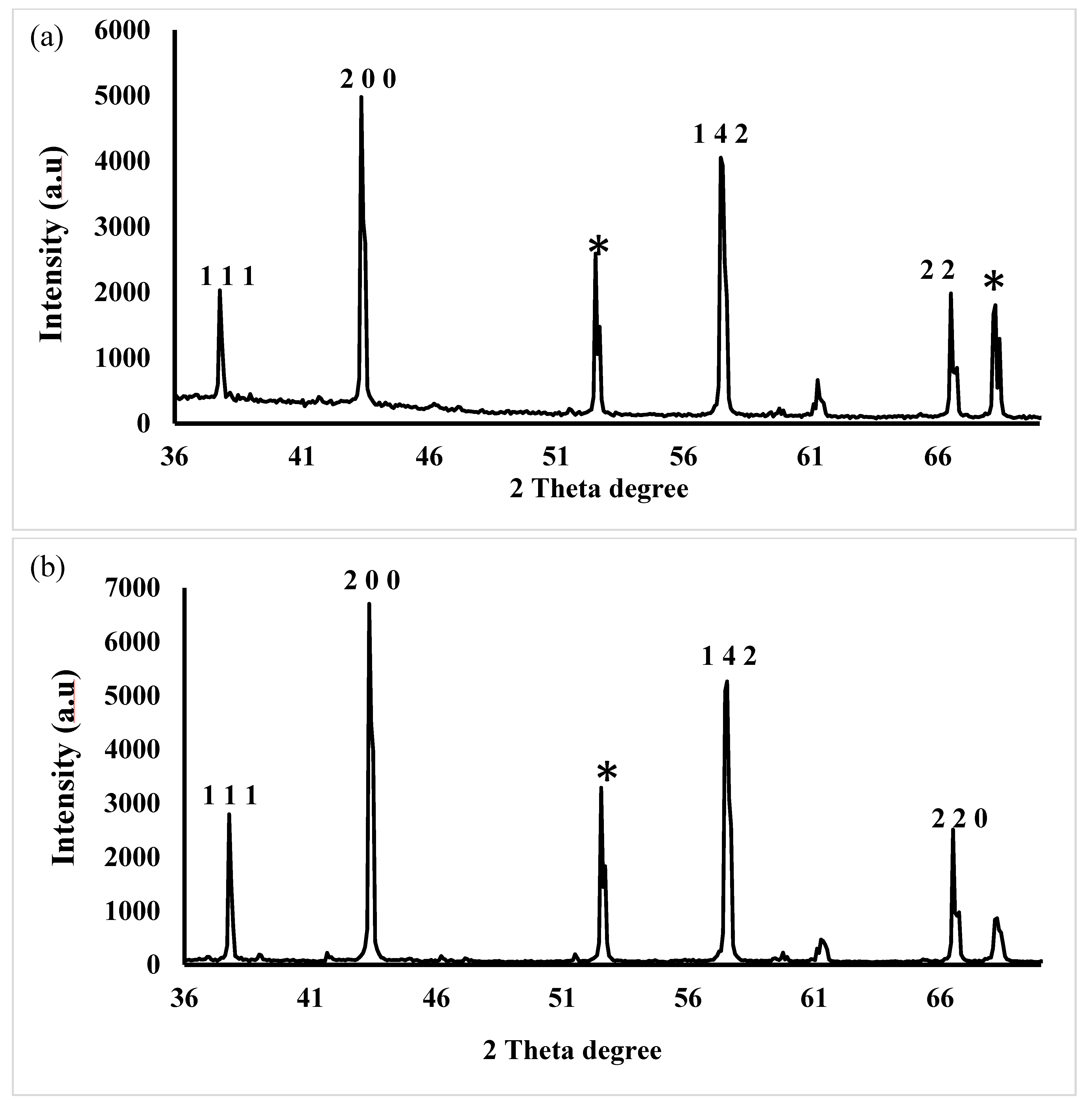

2.3.5. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

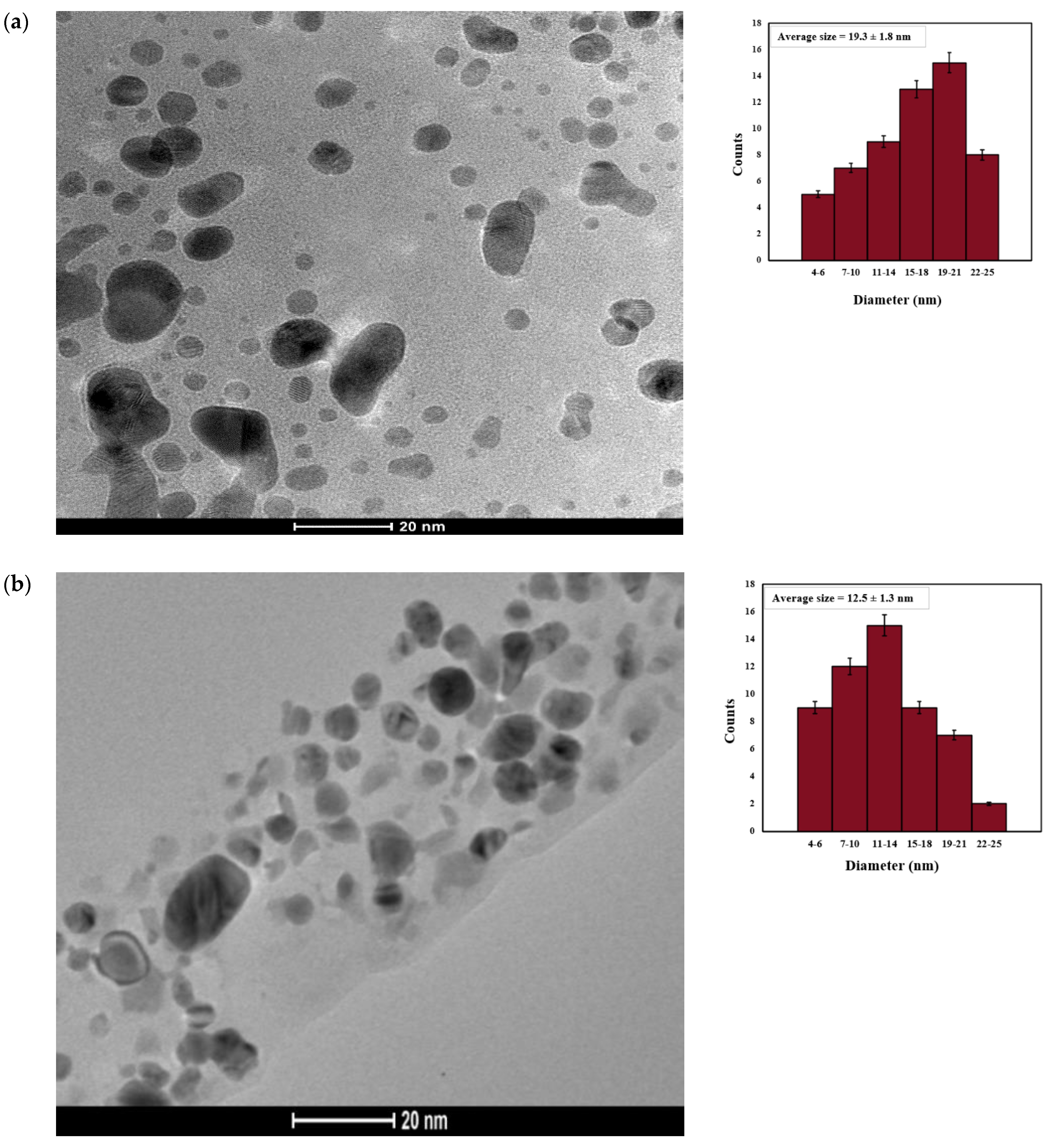

2.3.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.4. Analysis of Protein Corona Around AgNP

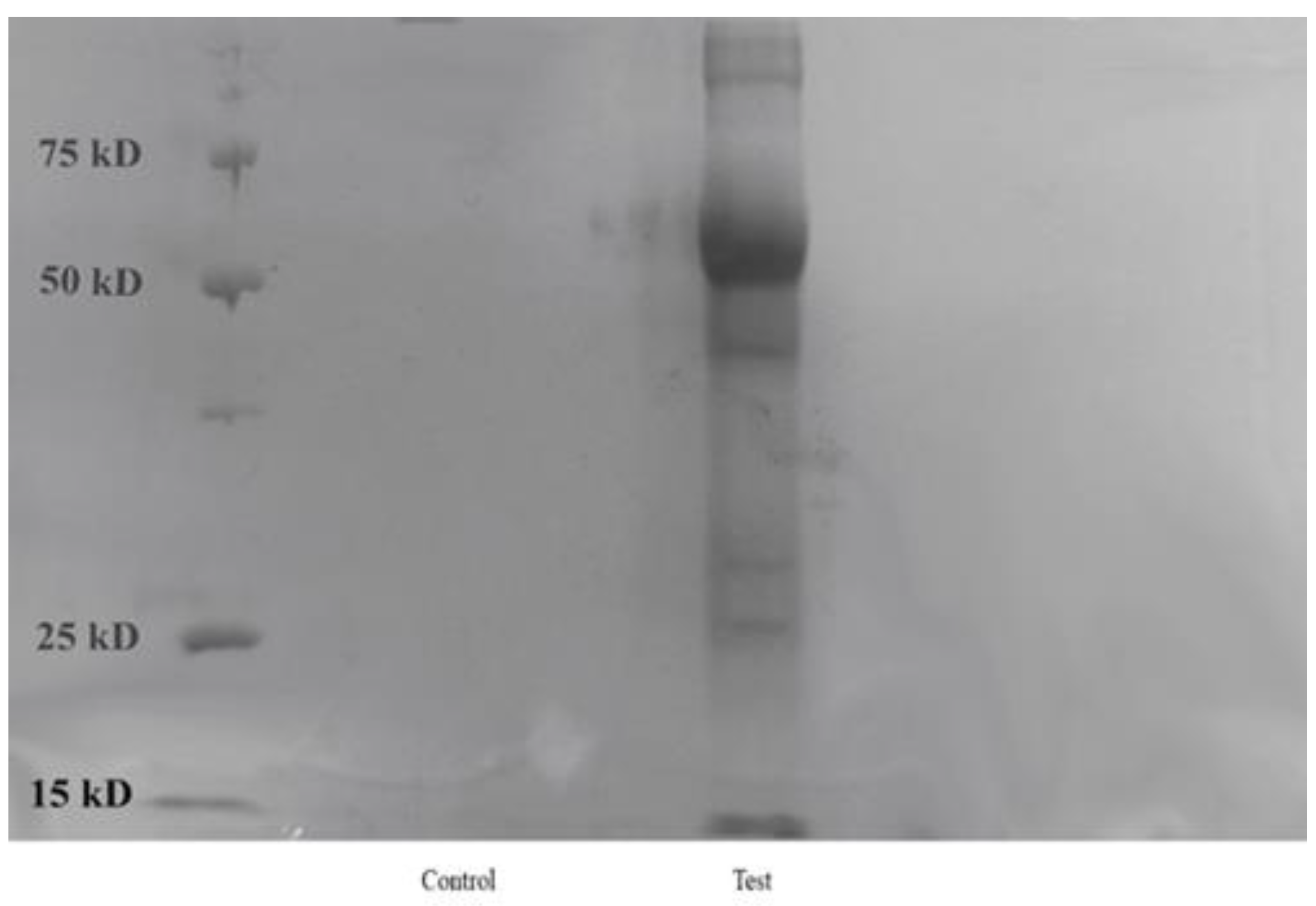

Gel Electrophoresis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mager, W.H.; Ferreira, P.M. Stress Response of Yeast. Biochem. J. 1993, 290(Pt. 1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, D.J. Oxidative Stress Responses of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1998, 14, 1511–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postaru, M.; Tucaliuc, A.; Cascaval, D.; Galaction, A.-I. Cellular Stress Impact on Yeast Activity in Biotechnological Processes—A Short Overview. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopandic, K. Saccharomyces Interspecies Hybrids as Model Organisms for Studying Yeast Adaptation to Stressful Environments. Yeast 2018, 35, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell, P.; Forment, J.V.; de Llanos, R.; Montón, F.; Llopis, S.; González, N.; Genovés, S.; Cienfuegos, E.; Monzó, H.; Ramón, D. Use of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans as Model Organisms to Study the Effect of Cocoa Polyphenols in the Resistance to Oxidative Stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2077–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, W.H.; Siderius, M. Novel Insights into the Osmotic Stress Response of Yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002, 2, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J.C.; Praekelt, U.M.; Meacock, P.A.; Planta, R.J.; Mager, W.H. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae HSP12 Gene Is Activated by the High-Osmolarity Glycerol Pathway and Negatively Regulated by Protein Kinase A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 6232–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, D.J. The Effect of Oxidative Stress on Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Redox Rep. 1995, 1, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruis, H.; Schüller, C. Stress Signaling in Yeast. Bioessays 1995, 17, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, G.M.; Richards, A.; Wahl, T.; Mao, C.; Obeid, L.; Hannun, Y. Involvement of Yeast Sphingolipids in the Heat Stress Response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae *. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 32566–32572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinnen, E.; Wanke, V.; Roosen, J.; Smets, B.; Dubouloz, F.; Pedruzzi, I.; Cameroni, E.; De Virgilio, C.; Winderickx, J. Rim15 and the Crossroads of Nutrient Signalling Pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Div. 2006, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, H.; Posas, F. Response to Hyperosmotic Stress. Genetics 2012, 192, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavelius, P.; Engelhart-Straub, S.; Biewald, A.; Haack, M.; Awad, D.; Brueck, T.; Mehlmer, N. Adaptation of Proteome and Metabolism in Different Haplotypes of Rhodosporidium toruloides during Cu(I) and Cu(II) Stress. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, E.A.; Weissman, J.S.; Horwich, A.L. Heat Shock Proteins and Molecular Chaperones: Mediators of Protein Conformation and Turnover in the Cell. Cell 1994, 78, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piper, P.W. The Heat Shock and Ethanol Stress Responses of Yeast Exhibit Extensive Similarity and Functional Overlap. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995, 134, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karreman, R.J.; Lindsey, G.G. A Rapid Method to Determine the Stress Status of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by Monitoring the Expression of a Hsp12: Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Construct under the Control of the Hsp12 Promoter. SLAS Discov. 2005, 10, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, K.; Brandt, W.; Rumbak, E.; Lindsey, G. The LEA-like Protein HSP 12 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Has a Plasma Membrane Location and Protects Membranes against Desiccation and Ethanol-Induced Stress. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2000, 1463, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motshwene, P.; Karreman, R.; Kgari, G.; Brandt, W.; Lindsey, G. LEA (Late Embryonic Abundant)-like Protein Hsp 12 (Heat-Shock Protein 12) Is Present in the Cell Wall and Enhances the Barotolerance of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 2004, 377, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karreman, R.J.; Dague, E.; Gaboriaud, F.; Quilès, F.; Duval, J.F.; Lindsey, G.G. The Stress Response Protein Hsp12p Increases the Flexibility of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cell Wall. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta BBA Proteins Proteom. 2007, 1774, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, Y.; Andoh, T.; Asahara, T.; Kikuchi, A. Yeast Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Activates Msn2p-Dependent Transcription of Stress Responsive Genes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boy-Marcotte, E.; Lagniel, G.; Perrot, M.; Bussereau, F.; Boudsocq, A.; Jacquet, M.; Labarre, J. The Heat Shock Response in Yeast: Differential Regulations and Contributions of the Msn2p/Msn4p and Hsf1p Regulons. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 33, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Pastor, M.T.; Marchler, G.; Schüller, C.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Ruis, H.; Estruch, F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Zinc Finger Proteins Msn2p and Msn4p Are Required for Transcriptional Induction through the Stress Response Element (STRE). EMBO J. 1996, 15, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Ward, M.P.; Garrett, S. Yeast PKA Represses Msn2p/Msn4p-dependent Gene Expression to Regulate Growth, Stress Response and Glycogen Accumulation. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 3556–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perwez, M.; Mazumder, J.A.; Noori, R.; Sardar, M. Magnetic combi CLEA for inhibition of bacterial biofilm: A green approach. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 186, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, F. Stress-Controlled Transcription Factors, Stress-Induced Genes and Stress Tolerance in Budding Yeast. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 24, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, K.A.; Grant, C.M.; Moye-Rowley, W.S. The Response to Heat Shock and Oxidative Stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2012, 190, 1157–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, Y.N.; Asnis, J.; Häfeli, U.O.; Bach, H. Metal Nanoparticles: Understanding the Mechanisms behind Antibacterial Activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamkhande, P.G.; Ghule, N.W.; Bamer, A.H.; Kalaskar, M.G. Metal Nanoparticles Synthesis: An Overview on Methods of Preparation, Advantages and Disadvantages, and Applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, C.-N.; Ho, C.-M.; Chen, R.; He, Q.-Y.; Yu, W.-Y.; Sun, H.; Tam, P.K.-H.; Chiu, J.-F.; Che, C.-M. Silver Nanoparticles: Partial Oxidation and Antibacterial Activities. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 12, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Qurashi, A.; Sheehan, D. Nano Packaging—Progress and Future Perspectives for Food Safety, and Sustainability. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 35, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Zhang, G. Effects of Different Nanoparticles on Microbes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Rojas, T.; Espinoza-Culupú, A.; Ramírez, P.; Iwai, L.K.; Montoni, F.; Macedo-Prada, D.; Sulca-López, M.; Durán, Y.; Farfán-López, M.; Herencia, J. Proteomic Study of Response to Copper, Cadmium, and Chrome Ion Stress in Yarrowia Lipolytica Strains Isolated from Andean Mine Tailings in Peru. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.; Chen, X.; Yang, G.; Lv, Y.; Liu, M.; Wehner, S.; Fischer, C.B. Gold Nanoparticles Bioproduced in Cyanobacteria in the Initial Phase Opened an Avenue for the Discovery of Corresponding Cerium Nanoparticles. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shah, T.; Ullah, R.; Zhou, P.; Guo, M.; Ovais, M.; Tan, Z.; Rui, Y. Review on Recent Progress in Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Diverse Applications. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 629054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabdallah, N.M.; Kotb, E. Antimicrobial Activity of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Waste Leaves of Hyphaene thebaica (Doum Palm). Microorganisms 2023, 11, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudagar, A.J.; Rangam, N.V.; Ruszczak, A.; Borowicz, P.; Tóth, J.; Kövér, L.; Michałowska, D.; Roszko, M.Ł.; Noworyta, K.R.; Lesiak, B. Valorization of Brewery Wastes for the Synthesis of Silver Nanocomposites Containing Orthophosphate. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelà, F.; Marsotto, M.; Meneghini, C.; Burratti, L.; Maraloiu, V.-A.; Iucci, G.; Venditti, I.; Prosposito, P.; D’Ezio, V.; Persichini, T.; et al. Biocompatible Silver Nanoparticles: Study of the Chemical and Molecular Structure, and the Ability to Interact with Cadmium and Arsenic in Water and Biological Properties. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, M.; Ansari, M.A.; Alzohairy, M.A.; Ali, S.G.; Khan, H.M.; Almatroudi, A.; Raees, K. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Oropharyngeal Candida glabrata Isolates and Their Antimicrobial Activity against Clinical Strains of Bacteria and Fungi. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Matpan Bekler, F.; Tunç, A.; Güven, K. The Effects of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) on Thermophilic Bacteria: Antibacterial, Morphological, Physiological and Biochemical Investigations. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghofaily, M.; Alfraih, J.; Alsaud, A.; Almazrua, N.; Sumague, T.S.; Auda, S.H.; Alsalleeh, F. The Effectiveness of Silver Nanoparticles Mixed with Calcium Hydroxide against Candida Albicans: An Ex Vivo Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzahaby, D.A.; Farrag, H.A.; Haikal, R.R.; Alkordi, M.H.; Abdeltawab, N.F.; Ramadan, M.A. Inhibition of Adherence and Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Immobilized ZnO Nanoparticles on Silicone Urinary Catheter Grafted by Gamma Irradiation. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kthiri, A.; Hamimed, S.; Othmani, A.; Landoulsi, A.; O’Sullivan, S.; Sheehan, D. Novel Static Magnetic Field Effects on Green Chemistry Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazumder, J.A.; Ahmad, R.; Sardar, M. Reusable Magnetic Nanobiocatalyst for Synthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.A.; Ahmed, T.; Wu, W.; Hossain, A.; Hafeez, R.; Islam Masum, M.M.; Wang, Y.; An, Q.; Sun, G.; Li, B. Advancements in Plant and Microbe-Based Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles and Their Antimicrobial Activity against Plant Pathogens. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kthiri, A.; Hamimed, S.; Tahri, W.; Landoulsi, A.; O’Sullivan, S.; Sheehan, D. Impact of Silver Ions and Silver Nanoparticles on Biochemical Parameters and Antioxidant Enzyme Modulations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under Co-Exposure to Static Magnetic Field: A Comparative Investigation. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 27, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, J.; Dhayalan, M.; Savaas Umar, M.R.; Gopal, M.; Ali Khan, M.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Cid-Samamed, A. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Allium cepa var. Aggregatum Natural Extract: Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Guo, J.; Long, X.; Pan, C.; Liu, G.; Peng, J. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Jasminum Nudiflorum Flower Extract and Their Antifungal and Antioxidant Activity. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, P.G.; De Matteis, V.; Pal, S.; Sangaru, S.S. Silver–Gold Alloy Nanoparticles (AgAu NPs): Photochemical Synthesis of Novel Biocompatible, Bimetallic Alloy Nanoparticles and Study of Their In Vitro Peroxidase Nanozyme Activity. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L. Biomedical Applications of Chinese Herb-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles by Phytonanotechnology. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S. Green Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles Using Plants. Green. Chem. 2011, 13, 2638–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, S.C. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Its Potential Application. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomah, A.A.; Zhang, Z.; Alamer, I.S.A.; Khattak, A.A.; Ahmed, T.; Hu, M.; Wang, D.; Xu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, Y. The Potential of Trichoderma-Mediated Nanotechnology Application in Sustainable Development Scopes. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novák, J.; Strašák, L.; Fojt, L.; Slaninová, I.; Vetterl, V. Effects of Low-Frequency Magnetic Fields on the Viability of Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bioelectrochemistry 2007, 70, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaka, M.; Ikehata, M.; Miyakoshi, J.; Ueno, S. Strong Static Magnetic Field Effects on Yeast Proliferation and Distribution. Bioelectrochemistry 2004, 65, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, A.A.; Kiechle, M.; Fellerhoff, B.; Eckardt-Schupp, F. Radiation-Induced Chromosome Aberrations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Influence of DNA Repair Pathways. Genetics 1998, 148, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbrot, D.R.; Khorkova, O.; Lin, H.; Henderson, A.S.; Goodman, R. The Effect of Low Frequency Electric and Magnetic Fields on Gene Expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 1993, 31, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kthiri, A.; Hidouri, S.; Wiem, T.; Jeridi, R.; Sheehan, D.; Landouls, A. Biochemical and Biomolecular Effects Induced by a Static Magnetic Field in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Evidence for Oxidative Stress. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.R.; Isikhuemhen, O.S.; Anike, F.N. Fungal–Metal Interactions: A Review of Toxicity and Homeostasis. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.R.; Isikhuemhen, O.S.; Anike, F.N.; Subedi, K. Physiological Response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Silver Stress. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroumand Moghaddam, A.; Namvar, F.; Moniri, M.; Tahir, P.M.; Azizi, S.; Mohamad, R. Nanoparticles Biosynthesized by Fungi and Yeast: A Review of Their Preparation, Properties, and Medical Applications. Molecules 2015, 20, 16540–16565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Prasad, K.; Kulkarni, A.R. Yeast Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2008, 4, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, Z.-J.; Liu, Y.-S.; Gao, X.-D.; Nakanishi, H. Studies on the Proteinaceous Structure Present on the Surface of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Spore Wall. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopac, T. Protein Corona, Understanding the Nanoparticle–Protein Interactions and Future Perspectives: A Critical Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 169, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miceli, E.; Kuropka, B.; Rosenauer, C.; Osorio Blanco, E.R.; Theune, L.E.; Kar, M.; Weise, C.; Morsbach, S.; Freund, C.; Calderón, M. Understanding the Elusive Protein Corona of Thermoresponsive Nanogels. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 2657–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Carrion, C.; Carril, M.; Parak, W.J. Techniques for the Experimental Investigation of the Protein Corona. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 46, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peigneux, A.; Glitscher, E.A.; Charbaji, R.; Weise, C.; Wedepohl, S.; Calderón, M.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Hedtrich, S. Protein Corona Formation and Its Influence on Biomimetic Magnetite Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 4870–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodbane, S.; Lahbib, A.; Sakly, M.; Abdelmelek, H. Bioeffects of Static Magnetic Fields: Oxidative Stress, Genotoxic Effects, and Cancer Studies. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 602987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano, M.B.; Delaunay, A.; Biteau, B.; Spector, D.; Azevedo, D. Oxidative Stress Responses in Yeast. In Yeast Stress Responses; Hohmann, S., Mager, W.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 241–303. ISBN 978-3-540-45611-7. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins During the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitha, S.L.; Nissamudeen, K.M.; Philip, D.; Gopchandran, K.G. Studies on Surface Plasmon Resonance and Photoluminescence of Silver Nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2008, 71, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, Y. Gold and Silver Nanoparticles: A Class of Chromophores with Colors Tunable in the Range from 400 to 750 Nm. Analyst 2003, 128, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasch, A.P.; Spellman, P.T.; Kao, C.M.; Carmel-Harel, O.; Eisen, M.B.; Storz, G.; Botstein, D.; Brown, P.O. Genomic Expression Programs in the Response of Yeast Cells to Environmental Changes. MBoC 2000, 11, 4241–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.O.; Alegre, R.M.; Garcia-Diego, C.; Cuellar, J. Effects of Magnetic Fields on Biomass and Glutathione Production by the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Process Biochem. 2010, 45, 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B.R.; Silva, P.G.P.; Garda-Buffon, J.; Santos, L.O. Magnetic Fields as Inducer of Glutathione and Peroxidase Production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 1881–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashiri, G.; Padilla, M.S.; Swingle, K.L.; Shepherd, S.J.; Mitchell, M.J.; Wang, K. Nanoparticle Protein Corona: From Structure and Function to Therapeutic Targeting. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 1432–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, E.; Jiang, K.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Qiu, H. The Crucial Role of a Protein Corona in Determining the Aggregation Kinetics and Colloidal Stability of Polystyrene Nanoplastics. Water Res. 2021, 190, 116742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, M.J.; Safavi-Sohi, R.; Sharifi, S.; Mahmoud, N.; Ashkarran, A.A.; Voke, E.; Serpooshan, V.; Ramezankhani, M.; Milani, A.S.; Landry, M.P.; et al. An Overview of Nanoparticle Protein Corona Literature. Small 2023, 19, 2301838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Bernfur, K.; Vilanova, M.; Cedervall, T. Understanding the Lipid and Protein Corona Formation on Different Sized Polymeric Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesaragandla, B.; Blessing, D.O.; Karanth, S.; Rong, A.; Geist, N.; Delcea, M. Interaction of polystyrene nanoparticles with supported lipid bilayers: Impact of nanoparticle size and protein corona. Macromol. Biosci. 2023, 23, 2200464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Peng, J.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Hu, Z.; Xu, G.; Wu, R. A Nano-Bio Interfacial Protein Corona on Silica Nanoparticle. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 167, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhao, L.; Guo, C.; Yan, B.; Su, G. Regulating Protein Corona Formation and Dynamic Protein Exchange by Controlling Nanoparticle Hydrophobicity. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Liu, Y.; Chandrasiri, I.; Overby, C.; Benoit, D.S.W. Impact of Nanoparticle Physicochemical Properties on Protein Corona and Macrophage Polarization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 13993–14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Days | Size (nm) and PDI of AgNP(Test) | Size (nm) and PDI of AgNP(Control) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 ± 1.5, 0.22 | 56 ± 3.2, 0.27 |

| 15 | 57 ± 1.76, 0.23 | 81 ± 3.8, 0.27 |

| 30 | 61 ± 1.54, 0.23 | 92 ± 4.1, 0.27 |

| 45 | 63 ± 2.1. 0.22 | 98 ± 3.9, 0.42 |

| 50 | 61 ± 2.3, 0.20 | 110 ± 2.7, 0.53 |

| 65 | 60.8 ± 1.87, 0.21 | 263 ± 5.3, 0.55 |

| 75 | 63.2 ± 1.01, 0.20 | 327 ± 4.21, 0.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ahmad, A.; Mazumder, J.A.; AbuShar, W.; Ouies, E.; Sheikh, A.Y.; Sheehan, D. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Response to Magnetic Stress: Role of a Protein Corona in Stable Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010178

Ahmad A, Mazumder JA, AbuShar W, Ouies E, Sheikh AY, Sheehan D. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Response to Magnetic Stress: Role of a Protein Corona in Stable Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010178

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmad, Atika, Jahirul Ahmed Mazumder, Wafa AbuShar, Emilia Ouies, Ashif Yasin Sheikh, and David Sheehan. 2026. "Saccharomyces cerevisiae Response to Magnetic Stress: Role of a Protein Corona in Stable Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010178

APA StyleAhmad, A., Mazumder, J. A., AbuShar, W., Ouies, E., Sheikh, A. Y., & Sheehan, D. (2026). Saccharomyces cerevisiae Response to Magnetic Stress: Role of a Protein Corona in Stable Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Microorganisms, 14(1), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010178