Frequency of Antimicrobial-Resistant Fecal Escherichia coli Among Small, Medium, and Large Beef Cow–Calf Operations in Florida

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cow–Calf Operations

2.2. Study Animals

2.3. Collection of Fecal Samples

2.4. Isolation of Fecal E. coli

2.5. E. coli Isolate Selection

2.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of E. coli from Fecal Samples

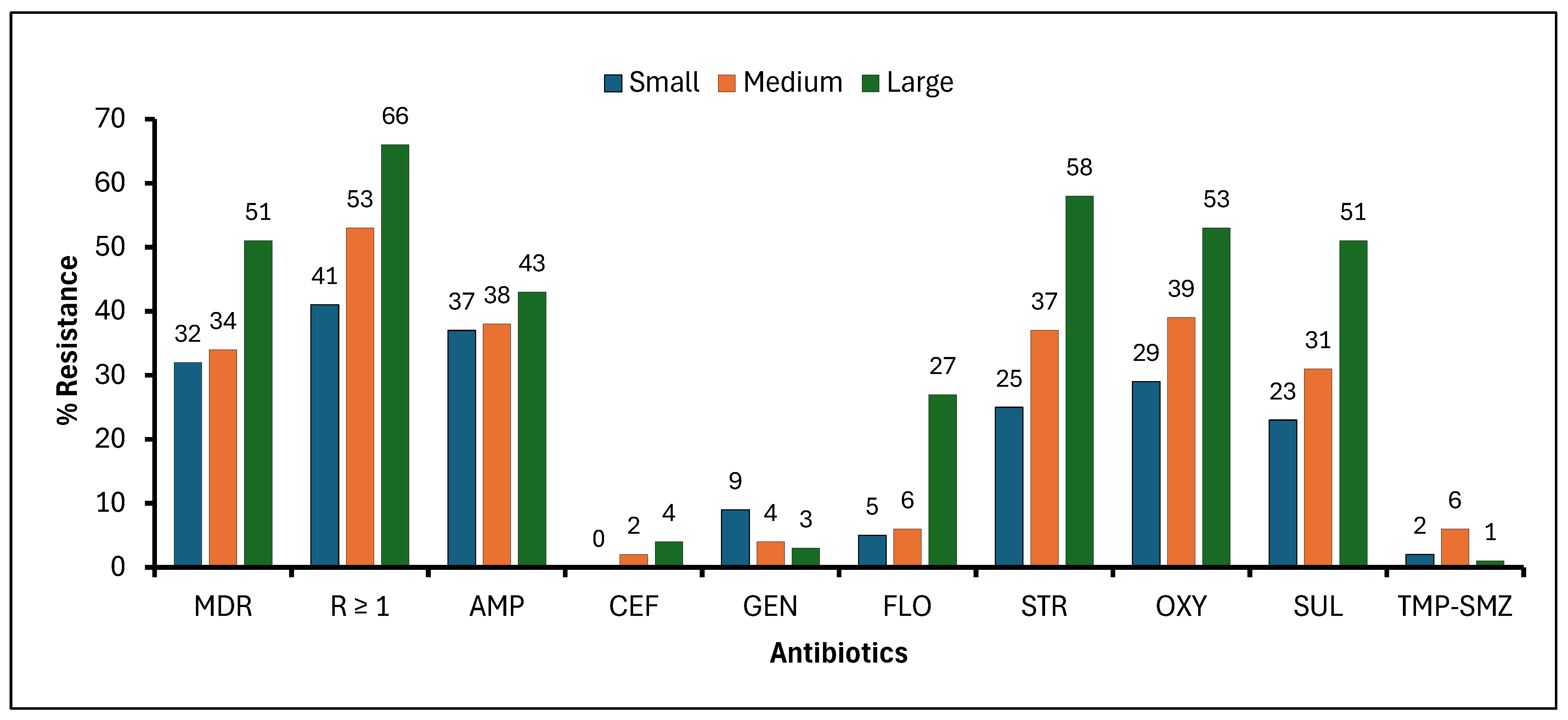

3.2. Frequency of Beef Cattle with E. coli Resistance to Selected Antibiotics Housed in Small, Medium, and Large Beef Cow–Calf Operations

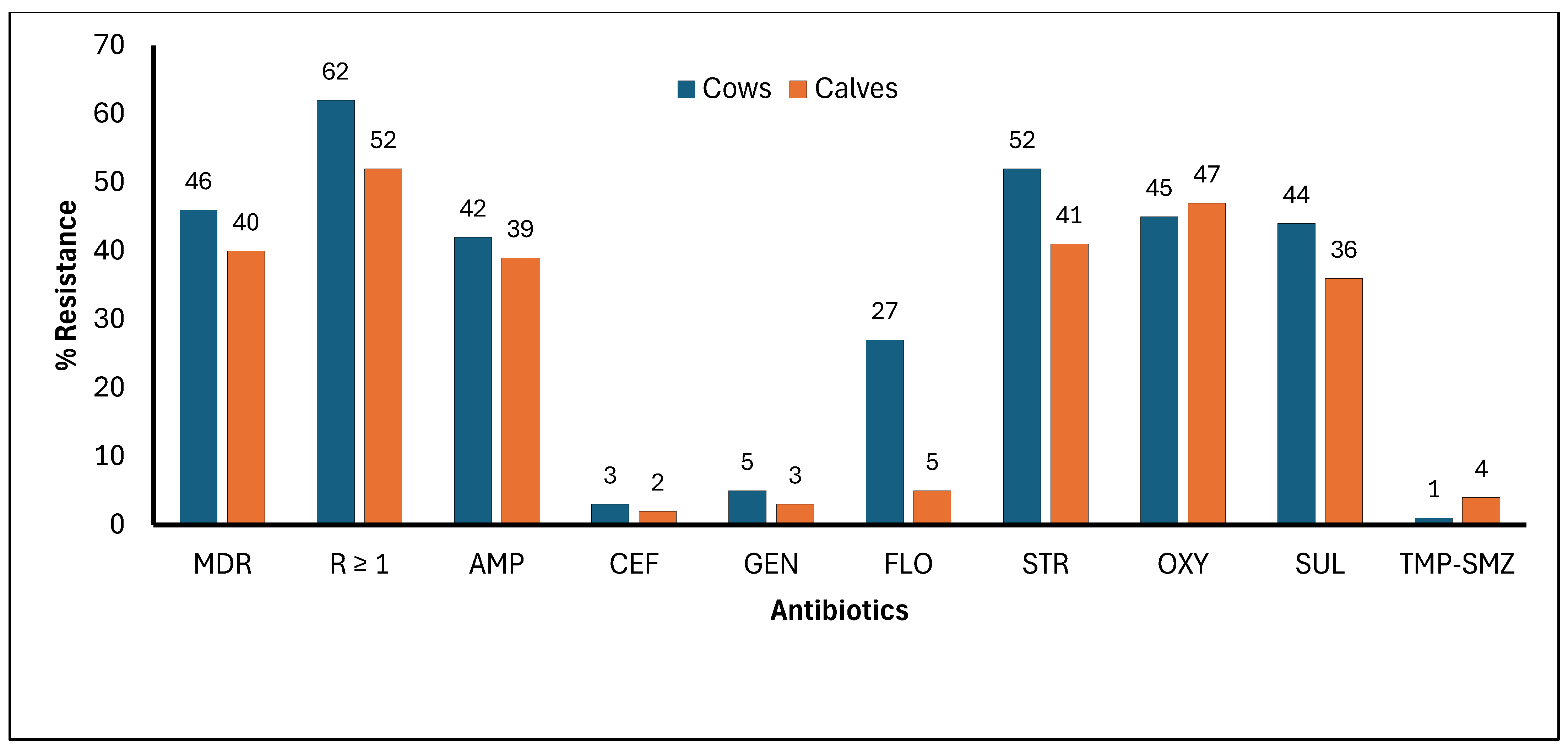

3.3. Frequency of Cows and Calves Diagnosed with E. coli Resistance to Selected Antibiotics

3.4. Relationship Between Farm Size (Small, Medium, and Large), Animal Type (Cows and Calves), and AMR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mathew, A.G.; Cissell, R.; Liamthong, S. Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteria Associated with Food Animals: A United States Perspective of Livestock Production. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2007, 4, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, L.B.; Graham, J.P.; Lackey, L.G.; Roess, A.; Vailes, R.; Silbergeld, E. Elevated Risk of Carrying Gentamicin-Resistant Escherichia coli among U.S. Poultry Workers. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 1738–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbergeld, E.K.; Graham, J.; Price, L.B. Industrial Food Animal Production, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Human Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bogaard, A.E.; Stobberingh, E.E. Epidemiology of Resistance to Antibiotics. Links between Animals and Humans. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2000, 14, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. 2016. Available online: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160525_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Grace, D. Review of Evidence on Antimicrobial Resistance and Animal Agriculture in Developing Countries. 2015. Available online: https://Hdl.Handle.Net/10568/67092 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Agga, G.E.; Schmidt, J.W.; Arthur, T.M. Antimicrobial-Resistant Fecal Bacteria from Ceftiofur-Treated and Nonantimicrobial-Treated Comingled Beef Cows at a Cow-Calf Operation. Microb. Drug Resist. 2016, 22, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.; McAllister, T.A. Antimicrobial Usage and Resistance in Beef Production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, A.; Stürmer, T.; Marre, R.; Brenner, H. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Escherichia coli: Overview of Geographical, Temporal, and Methodological Variations. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 26, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Denagamage, T.; Hernandez, J.A.; Bittar, J.H.J.; Lee, A.C.Y.; Jeong, K.C.; Kariyawasam, S. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Antimicrobial-Resistant Fecal Bacteria in Beef Cow-Calf Operations: A Systematic Review. Res. Vet. Sci. 2025, 193, 105761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Beef 2017: Beef Cow-Calf Health and Management Practices in the United States, 2017, Report 2. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/beef-2017-part2.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjO_uvthsGRAxWdn68BHbQLAy4QFnoECBsQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2IsA-nHmrySr3pLaYbbDDq (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Markland, S.; Weppelmann, T.A.; Ma, Z.; Lee, S.; Mir, R.A.; Teng, L.; Ginn, A.; Lee, C.; Ukhanova, M.; Galindo, S.; et al. High Prevalence of Cefotaxime Resistant Bacteria in Grazing Beef Cattle: A Cross Sectional Study. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA); National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS); Agricultural Statistics Board. Cattle. 31 January 2025. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://esmis.nal.usda.gov/sites/default/release-files/h702q636h/sf26b275x/h989sz55j/catl0125.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjpxeWfh8GRAxUsafUHHWZbMQ8QFnoECBwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2M3lHfjuQG0phbM90AA55G (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Berge, A.C.; Hancock, D.D.; Sischo, W.M.; Besser, T.E. Geographic, Farm, and Animal Factors Associated with Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance in Fecal Escherichia coli Isolates from Cattle in the Western United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2010, 236, 1338–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, L.; Albini, E.; Lovito, C.; Blasi, F.; Maresca, C.; Massacci, F.R.; Orsini, S.; Tofani, S.; Pezzotti, G.; Diaz Vicuna, E.; et al. Antibiotic Consumption Is a Major Driver of Antibiotic Resistance in Calves Raised on Italian Cow-Calf Beef Farms. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 145, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2009, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C.; Wickramasingha, D.; Abdelfattah, E.M.; Pereira, R.V.; Okello, E.; Maier, G. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Fecal Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. Isolates from Beef Cow-Calf Operations in Northern California and Associations with Farm Practices. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1086203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vineetha, N.; Vignesh, R.A.; Sridhar, D. Preparation, Standardization of Antibiotic Discs and Study of Resistance Pattern for First-Line Antibiotics in Isolates from Clinical Samples. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2015, 11, 624–631. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI VET01S; Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated from Animals, 7th ed. CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024.

- Benedict, K.M.; Gow, S.P.; Checkley, S.; Booker, C.W.; McAllister, T.A.; Morley, P.S. Methodological Comparisons for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Feedlot Cattle. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Fan, P.; Liu, T.; Yang, A.; Boughton, R.K.; Pepin, K.M.; Miller, R.S.; Jeong, K.C. Transmission of Antibiotic Resistance at the Wildlife-Livestock Interface. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, B.; Fossen, J.; Gow, S.; Waldner, C. A Scoping Review of Antimicrobial Usage and Antimicrobial Resistance in Beef Cow–Calf Herds in the United States and Canada. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, S.P.; Waldner, C.L.; Rajić, A.; McFall, M.E.; Reid-Smith, R. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Fecal Generic Escherichia coli Isolated in Western Canadian Cow-Calf Herds. Part I—Beef Calves. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2008, 72, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; et al. Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) during Animal Transport. EFSA 2022, 20, e07586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bava, R.; Castagna, F.; Lupia, C.; Poerio, G.; Liguori, G.; Lombardi, R.; Naturale, M.D.; Mercuri, C.; Bulotta, R.M.; Britti, D.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock: A Serious Threat to Public Health. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, B.J.A.; Roelofs, G.; Van Zanten, B.; Driessen-van Lankveld, W.D.M.; Pikkemaat, M.G.; Bongers, I.E.A.; De Lange, E. A Strategy to Determine the Fate of Active Chemical Compounds in Soil; Applied to Antimicrobially Active Substances. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, R.A.; Weppelmann, T.A.; Teng, L.; Kirpich, A.; Elzo, M.A.; Driver, J.D.; Jeong, K.C. Colonization Dynamics of Cefotaxime Resistant Bacteria in Beef Cattle Raised Without Cephalosporin Antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, D.A.; Zhao, S.; Tong, E.; Ayers, S.; Singh, A.; Bartholomew, M.J.; McDermott, P.F. Antimicrobial Drug Resistance in Escherichia coli from Humans and Food Animals, United States, 1950–2002. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, C.A.; Reid-Smith, R.; Irwin, R.J.; Martin, W.S.; McEwen, S.A. Antimicrobial Resistance in Generic Fecal Escherichia coli from 29 Beef Farms in Ontario. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2008, 72, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waldner, C.L.; Gow, S.; Parker, S.; Campbell, J.R. Antimicrobial Resistance in Fecal Escherichia coli and Campylobacter spp. from Beef Cows in Western Canada and Associations with Herd Attributes and Antimicrobial Use. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2019, 83, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gow, S.P.; Waldner, C.L.; Harel, J.; Boerlin, P. Associations between Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Fecal Generic Escherichia coli Isolates from Cow-Calf Herds in Western Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 3658–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, S.P.; Waldner, C.L. Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Factors Stx1, Stx2, and Eae in Generic Escherichia coli Isolates from Calves in Western Canadian Cow-Calf Herds. Microb. Drug Resist. 2009, 15, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, E.M.; Ekong, P.S.; Okello, E.; Chamchoy, T.; Karle, B.M.; Black, R.A.; ElAshmawy, W.; Sheedy, D.; Williams, D.R.; Lehenbauer, T.W.; et al. Antimicrobial Drug Use and Its Association with Antimicrobial Resistance in Fecal Commensals from Cows on California Dairies. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1504640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueger, E.L.; Angelos, J.A.; Cosgrove, S.; Johnson, J.; George, L.W. Efficacy of Florfenicol in the Treatment of Experimentally Induced Infectious Bovine Keratoconjunctivitis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1999, 60, 960–964. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.J.; Kang, S.G.; Nabin, R.; Kang, M.L.; Yoo, H.S. Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Activity of Florfenicol against Bacteria Isolated from Bovine and Porcine Respiratory Disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2005, 106, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehrenberg, C.; Schwarz, S. Distribution of Florfenicol Resistance Genes fexA and Cfr among Chloramphenicol-Resistant Staphylococcus Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halleran, J.; Sylvester, H.; Jacob, M.; Callahan, B.; Baynes, R.; Foster, D. Impact of Florfenicol Dosing Regimen on the Phenotypic and Genotypic Resistance of Enteric Bacteria in Steers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, S.P.; Waldner, C.L.; Rajić, A.; McFall, M.E.; Reid-Smith, R. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Fecal Generic Escherichia coil Isolated in Western Canadian Beef Herds. Part II—Cows Cow-Calf Pairs. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2008, 72, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Malavez, Y.; Nieves-Miranda, S.M.; Loperena Gonzalez, P.N.; Padin-Lopez, A.F.; Xiaoli, L.; Dudley, E.G. Exploring Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of E. coli Isolates in Dairy Cattle: A Baseline Study across Dairy Farms with Varied Husbandry Practices in Puerto Rico. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Beef Cow–Calf Operations | Size | Number of Samples Collected | Number of Samples Tested for AST | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cows | Calves | Cows | Calves | ||

| #1 | Small | 22 | 11 | 20 | 10 |

| #2 | 18 | 9 | 18 | 9 | |

| #3 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 17 | |

| #4 | Medium | 48 | 29 | 42 | 26 |

| #5 | 44 | 30 | 40 | 28 | |

| #6 | 32 | 30 | 31 | 28 | |

| #7 | Large | 79 | 62 | 76 | 58 |

| #8 | 82 | 65 | 78 | 61 | |

| #9 | 85 | 60 | 80 | 55 | |

| Total | 429 | 314 | 403 | 292 | |

| 743 | 695 | ||||

| Antibiotic | Variable | Category | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-drug resistance | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 1.19 | 0.55–2.56 | 0.602 | ||

| Large | 2.17 | 1.14–4.00 | 0.023 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 1.05 | 0.64–1.75 | 0.797 | ||

| R ≥ 1 antibiotic | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 1.67 | 1.28–2.13 | 0.002 | ||

| Large | 2.70 | 1.49–5.00 | 0.006 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 1.15 | 0.81–1.61 | 0.3569 | ||

| Ampicillin | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 1.06 | 0.69–1.61 | 0.753 | ||

| Large | 1.20 | 0.62–2.38 | 0.509 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 0.99 | 0.81–1.23 | 0.954 | ||

| Ceftiofur * | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | ND | ND | ND | ||

| Large | ND | ND | ND | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | ND | ND | ND | ||

| Gentamicin | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 0.44 | 0.20–0.99 | 0.048 | ||

| Large | 0.23 | 0.08–0.60 | 0.010 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 1.64 | 0.51–5.56 | 0.342 | ||

| Florfenicol | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 0.80 | 0.05–11.11 | 0.844 | ||

| Large | 4.00 | 1.19–12.50 | 0.031 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 3.57 | 1.22–11.11 | 0.028 | ||

| Streptomycin | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 1.92 | 0.96–4.00 | 0.062 | ||

| Large | 4.17 | 2.50–6.67 | <0.001 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 1.41 | 0.86–2.27 | 0.137 | ||

| Oxytetracycline | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 1.54 | 0.60–4.00 | 0.309 | ||

| Large | 2.44 | 1.08–5.26 | 0.035 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 0.67 | 0.27–1.64 | 0.314 | ||

| Sulfadimethoxine | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 1.64 | 1.03–2.63 | 0.042 | ||

| Large | 3.45 | 2.56–4.76 | <0.001 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 1.29 | 0.86–1.96 | 0.169 | ||

| Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole | Farm size | Small | 1.00 | - | NA |

| Medium | 1.45 | 0.14–14.3 | 0.712 | ||

| Large | 0.47 | 0.05–4.76 | 0.453 | ||

| Animal type | Cow | 1.00 | - | NA | |

| Calf | 0.49 | 0.14–1.79 | 0.225 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ali, A.; Bittar, J.H.J.; Edison, L.K.; Colee, J.; Denagamage, T.; Hernandez, J.A.; Kariyawasam, S. Frequency of Antimicrobial-Resistant Fecal Escherichia coli Among Small, Medium, and Large Beef Cow–Calf Operations in Florida. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010013

Ali A, Bittar JHJ, Edison LK, Colee J, Denagamage T, Hernandez JA, Kariyawasam S. Frequency of Antimicrobial-Resistant Fecal Escherichia coli Among Small, Medium, and Large Beef Cow–Calf Operations in Florida. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Ahmad, João H. J. Bittar, Lekshmi K. Edison, James Colee, Thomas Denagamage, Jorge A. Hernandez, and Subhashinie Kariyawasam. 2026. "Frequency of Antimicrobial-Resistant Fecal Escherichia coli Among Small, Medium, and Large Beef Cow–Calf Operations in Florida" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010013

APA StyleAli, A., Bittar, J. H. J., Edison, L. K., Colee, J., Denagamage, T., Hernandez, J. A., & Kariyawasam, S. (2026). Frequency of Antimicrobial-Resistant Fecal Escherichia coli Among Small, Medium, and Large Beef Cow–Calf Operations in Florida. Microorganisms, 14(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010013