Superior RdRp Function Drives the Dominance of Prevalent GI.3 Norovirus Lineages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence Data Collection

2.2. Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Rate Analysis

2.3. RdRp Protein Expression and Purification

2.4. RdRp Enzymatic Activity Assay

2.5. Enzyme Kinetics Assay

3. Results

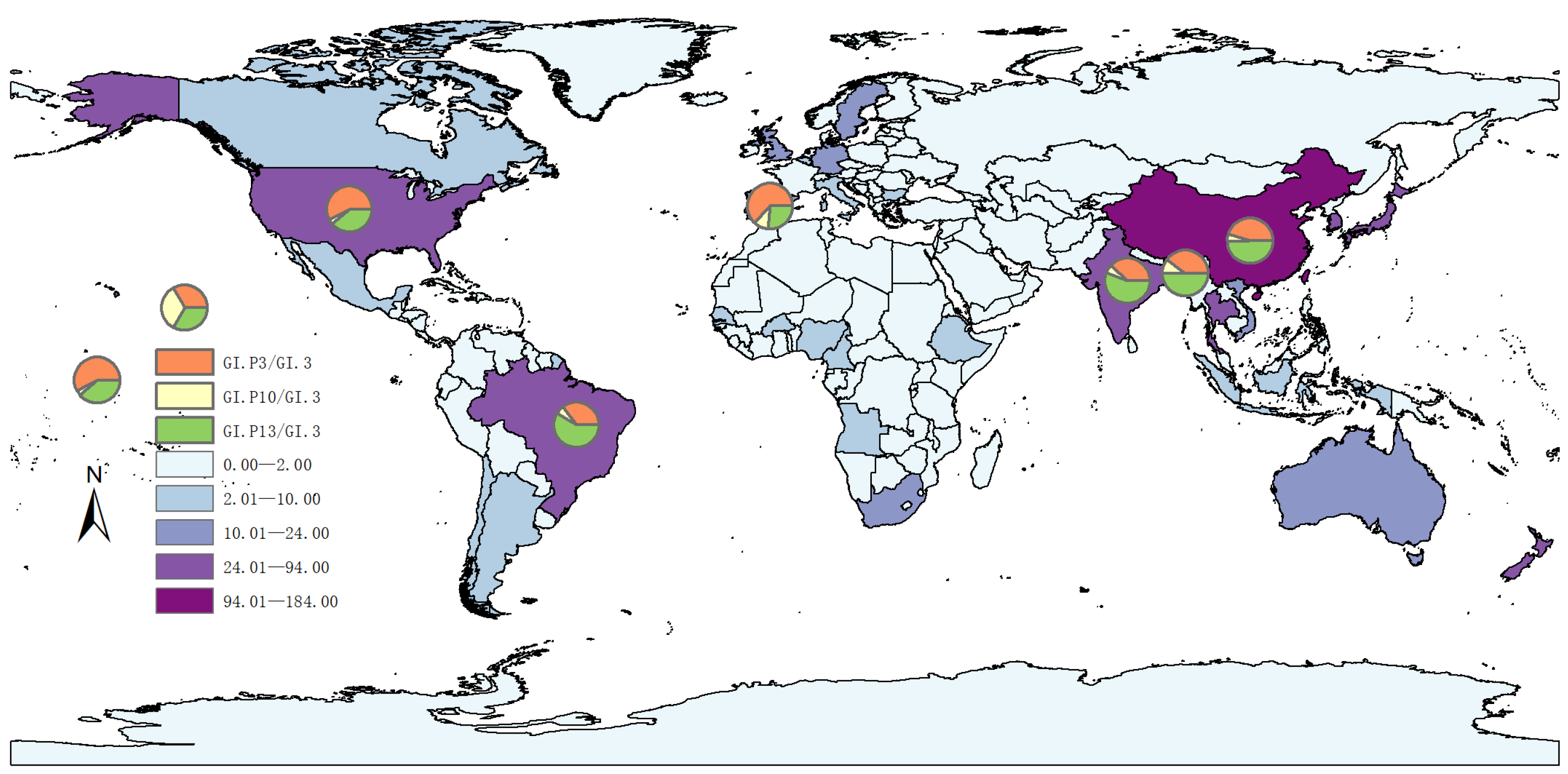

3.1. Genomic Epidemiology of GI.3 NoV

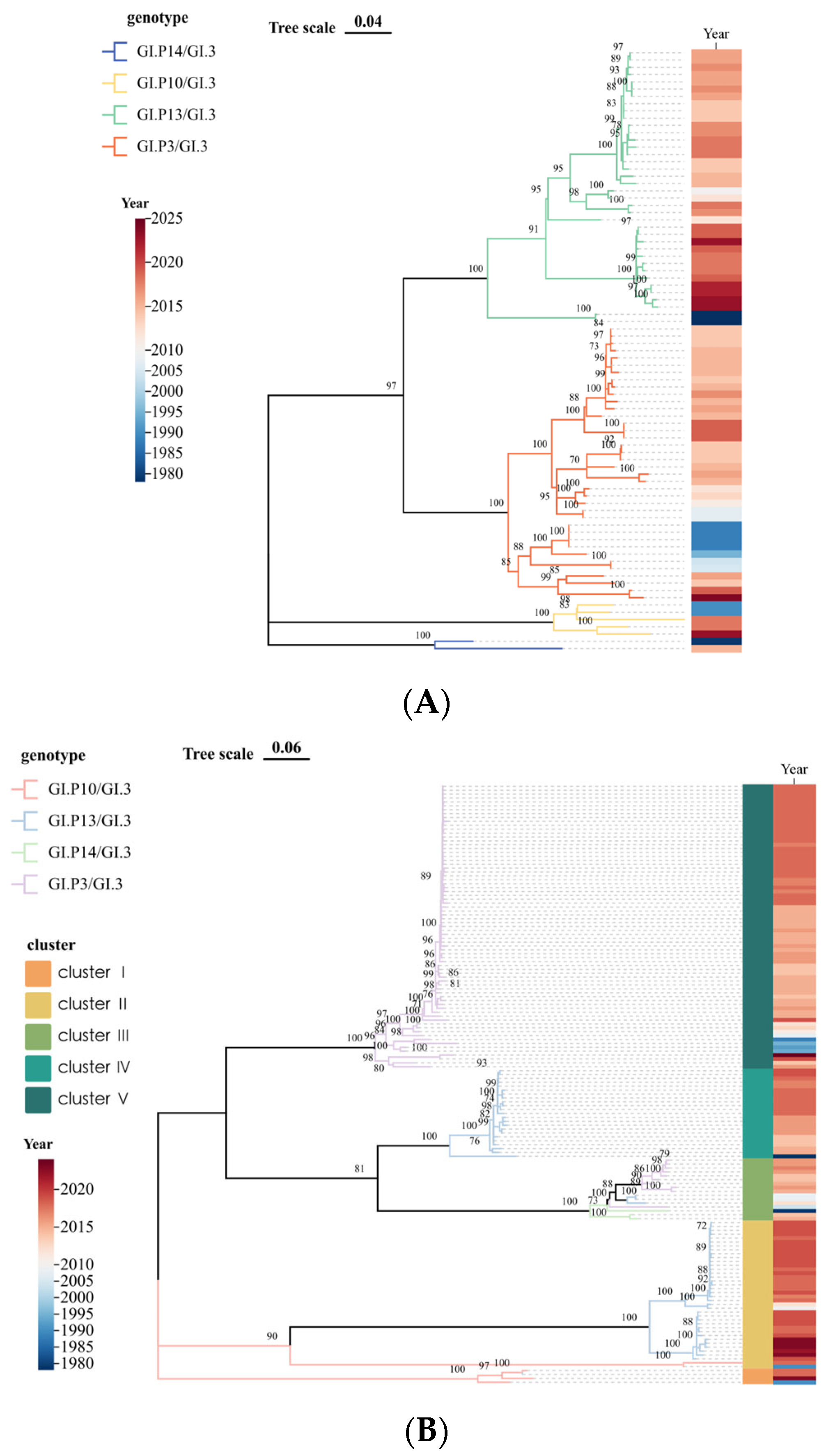

3.2. Genetic Characterization

3.3. Time-Scale Evolutionary Characterization

3.4. Expression and Verification of GI.3 NoV RdRp Proteins

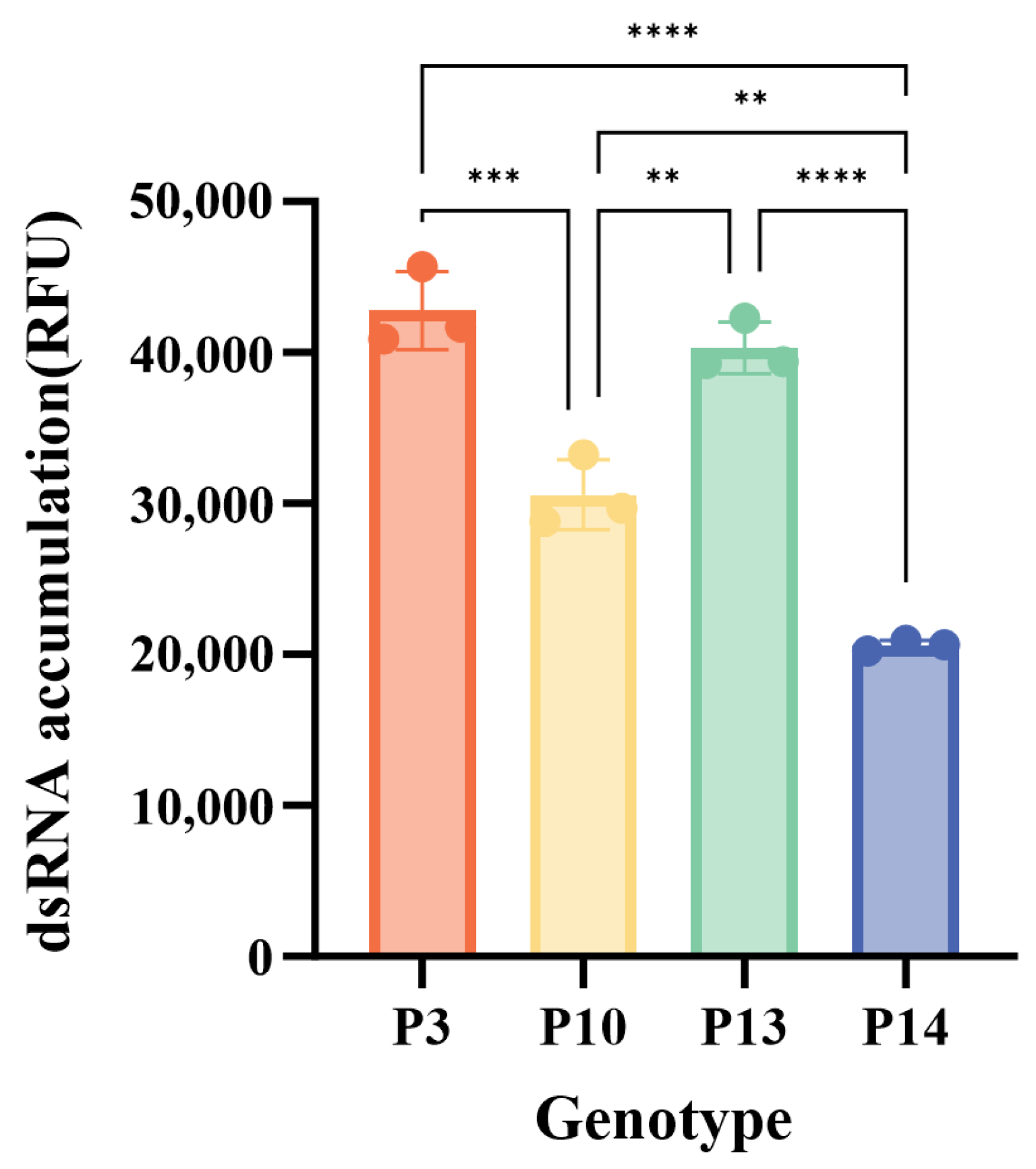

3.5. Characterization of GI.3 NoV RdRp Activity

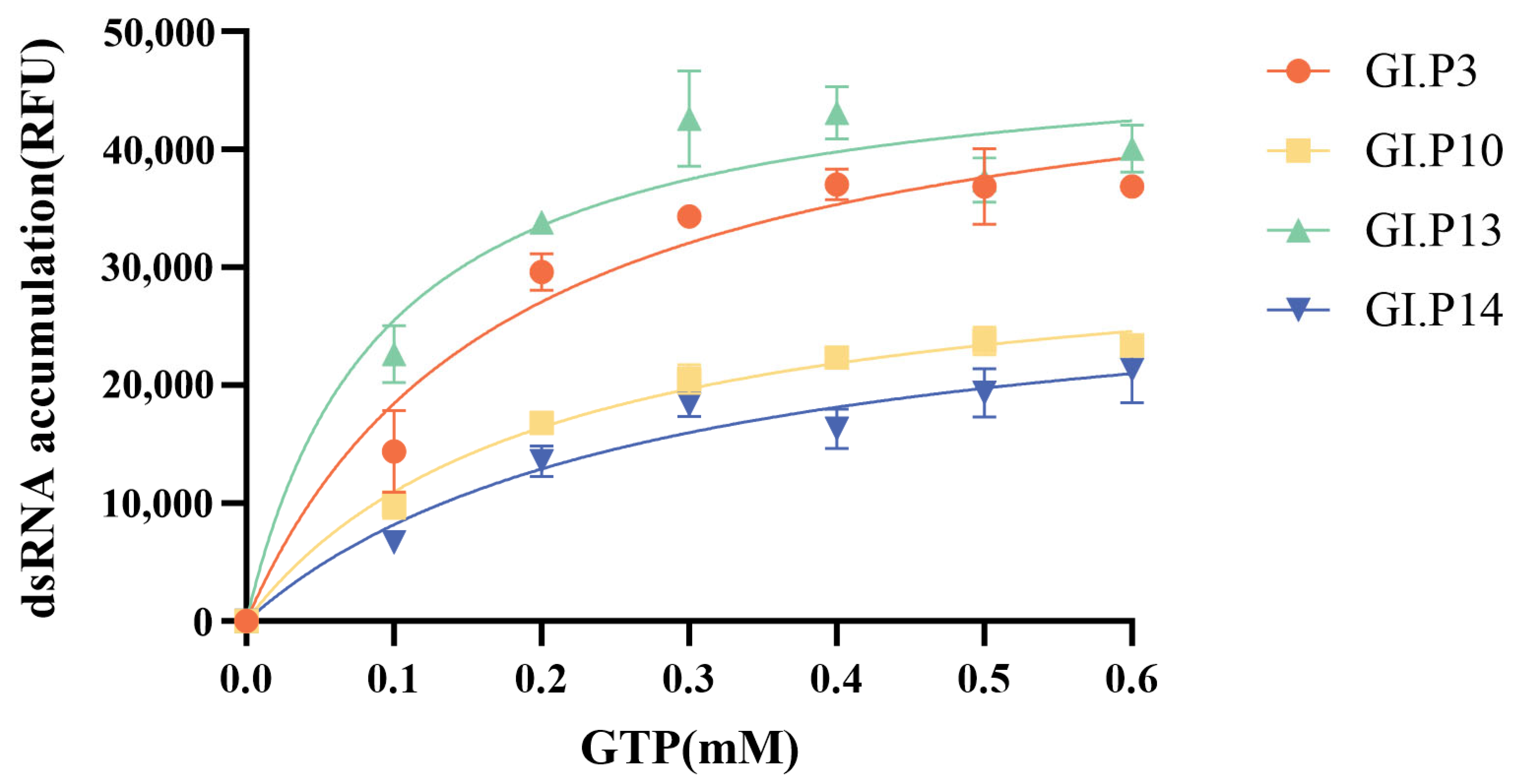

3.6. Substrate Kinetics of GI.3 NoV RdRp

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NoV | norovirus |

| RdRp | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| VP1 | major capsid protein |

| ORFs | open reading frames |

| HBGAs | histo-blood group antigens |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| ML | maximum likelihood |

| MCMC | Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| HPD | highest posterior density |

| ESS | effective sample size |

| bp | base pairs |

| nt | nucleotide |

| dsRNA | double-stranded RNA |

| RFU | relative fluorescence unit |

| Km | Michaelis constant |

| Vmax | maximum velocity |

References

- Netzler, N.E.; Enosi Tuipulotu, D.; White, P.A. Norovirus Antivirals: Where Are We Now? Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 860–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, T.G.; Olortegui, M.P.; Kosek, M.N. Viral Gastroenteritis. Lancet 2024, 403, 862–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, M.; van Beek, J.; Koopmans, M.P.G. Human Norovirus Transmission and Evolution in a Changing World. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopman, B.A.; Steele, D.; Kirkwood, C.D.; Parashar, U.D. The Vast and Varied Global Burden of Norovirus: Prospects for Prevention and Control. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Fang, L.; Sun, L.; Zeng, H.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wu, S.; Yang, F.; Song, T.; Lin, J.; et al. Association of GII.P16-GII.2 Recombinant Norovirus Strain with Increased Norovirus Outbreaks, Guangdong, China, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Kimura, R.; Shirai, T.; Sada, M.; Sugai, T.; Murakami, K.; Harada, K.; Ito, K.; Matsushima, Y.; Mizukoshi, F.; et al. Molecular Evolutionary Analyses of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp) Region and VP1 Gene in Human Norovirus Genotypes GII.P6-GII.6 and GII.P7-GII.6. Viruses 2023, 15, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y.A.; Orlov, A.V.; Lukashev, A.N.; Vakulenko, Y.A.; Orlov, A.V.; Lukashev, A.N. Patterns and Temporal Dynamics of Natural Recombination in Noroviruses. Viruses 2023, 15, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, L.; Li, Y.; Cheng, T.; Meng, L.; Li, Y.; Cai, W.; Hong, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. GII.17[P17] and GII.8[P8] Noroviruses Showed Different RdRp Activities Associated with Their Epidemic Characteristics. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Jiang, X. Norovirus-Host Interaction: Multi-Selections by Human HBGAs. Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindesmith, L.C.; Debbink, K.; Swanstrom, J.; Vinjé, J.; Costantini, V.; Baric, R.S.; Donaldson, E.F. Monoclonal Antibody-Based Antigenic Mapping of Norovirus GII.4-2002. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, E.F.; Lindesmith, L.C.; Lobue, A.D.; Baric, R.S. Norovirus Pathogenesis: Mechanisms of Persistence and Immune Evasion in Human Populations. Immunol. Rev. 2008, 225, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, J.; De Graaf, M.; Al-Hello, H.; Allen, D.J.; Ambert-Balay, K.; Botteldoorn, N.; Brytting, M.; Buesa, J.; Cabrerizo, M.; Chan, M.; et al. Molecular Surveillance of Norovirus, 2005–2016: An Epidemiological Analysis of Data Collected from the NoroNet Network. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-R.; Xie, D.-J.; Li, J.-H.; Koroma, M.M.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Jing, D.-N.; Xu, J.-Y.; Yu, J.-X.; Du, H.-S.; et al. Serological Surveillance of GI Norovirus Reveals Persistence of Blockade Antibody in a Jidong Community-Based Prospective Cohort, 2014–2018. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1258550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, D.I.; Witt, J.; Rostant, W.; Burton, R.; Davison, V.; Ditchburn, J.; Evens, N.; Godwin, R.; Heywood, J.; Lowther, J.A.; et al. Piloting Wastewater-Based Surveillance of Norovirus in England. Water Res. 2024, 263, 122152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, B.; Shrestha, S.; Sthapit, N.; Hirai, S.; Raya, S.; Rahmani, A.F.; Angga, M.S.; Siri, Y.; Ruti, A.A.; Haramoto, E. Beyond COVID-19: Wastewater-Based Epidemiology for Multipathogen Surveillance and Normalization Strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumthip, K.; Khamrin, P.; Thongprachum, A.; Malasao, R.; Yodmeeklin, A.; Ushijima, H.; Maneekarn, N. Diverse Genotypes of Norovirus Genogroup I and II Contamination in Environmental Water in Thailand during the COVID-19 Outbreak from 2020 to 2022. Virol. Sin. 2024, 39, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Huang, Q.; Qin, L.; Zhong, X.; Li, H.; Chen, R.; Wan, Z.; Lin, H.; Liang, J.; Li, J.; et al. Epidemiological Characteristics of Asymptomatic Norovirus Infection in a Population from Oyster (Ostrea Rivularis Gould) Farms in Southern China. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Liang, M.; Zhao, F.; Su, L. Research Progress on Biological Accumulation, Detection and Inactivation Technologies of Norovirus in Oysters. Foods 2023, 12, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.V.V.; Atmar, R.L.; Ramani, S.; Palzkill, T.; Song, Y.; Crawford, S.E.; Estes, M.K. Norovirus Replication, Host Interactions and Vaccine Advances. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Lleó, N.; Santiso-Bellón, C.; Vila-Vicent, S.; Carmona-Vicente, N.; Gozalbo-Rovira, R.; Cárcamo-Calvo, R.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.; Buesa, J. Recombinant Noroviruses Circulating in Spain from 2016 to 2020 and Proposal of Two Novel Genotypes within Genogroup I. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0250521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, G.; Cai, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree Visualization by One Table (tvBOT): A Web Application for Visualizing, Modifying and Annotating Phylogenetic Trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W587–W592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis by Sampling Trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchard, M.A.; Lemey, P.; Baele, G.; Ayres, D.L.; Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. Bayesian Phylogenetic and Phylodynamic Data Integration Using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vey016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monjezi, R.; Tey, B.T.; Sieo, C.C.; Tan, W.S. Purification of Bacteriophage M13 by Anion Exchange Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B 2010, 878, 1855–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohayem, J.; Robel, I.; Jäger, K.; Scheffler, U.; Rudolph, W. Protein-Primed and de Novo Initiation of RNA Synthesis by Norovirus 3Dpol. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7060–7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, M.; Jin, H. Molecular Evolution of RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Region in Norovirus Genogroup I. Viruses 2023, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamrin, P.; Kumthip, K.; Yodmeeklin, A.; Okitsu, S.; Motomura, K.; Sato, S.; Ushijima, H.; Maneekarn, N. Genetic Recombination and Genotype Diversity of Norovirus GI in Children with Acute Gastroenteritis in Thailand, 2015–2021. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degiuseppe, J.I.; Barclay, L.; Gomes, K.A.; Costantini, V.; Vinjé, J.; Stupka, J.A. Molecular Epidemiology of Norovirus Outbreaks in Argentina, 2013–2018. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1330–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordgren, J.; Kindberg, E.; Lindgren, P.E.; Matussek, A.; Svensson, L. Norovirus Gastroenteritis Outbreak with a Secretor-Independent Susceptibility Pattern, Sweden. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, L.; Cannon, J.L.; Wikswo, M.E.; Phillips, A.R.; Browne, H.; Montmayeur, A.M.; Tatusov, R.L.; Burke, R.M.; Hall, A.J.; Vinjé, J. Emerging Novel GII.P16 Noroviruses Associated with Multiple Capsid Genotypes. Viruses 2019, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Fu, J.; Liu, B.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Jia, L.; Yang, P.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; et al. Genotype Diversity and Evolution of Noroviruses GI.3[P13] Associated Acute Gastroenteritis Outbreaks in Beijing, China from 2016 to 2019. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2025, 136, 105850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Banzhaf, W.; Moore, J.H. The Effects of Recombination on Phenotypic Exploration and Robustness in Evolution. Artif. Life 2014, 20, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, J.; Lässig, M.; Mora, T.; Walczak, A.M. Multi-Lineage Evolution in Viral Populations Driven by Host Immune Systems. Pathogens 2019, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.F.; Lemey, P.; Jiang, X.; Lam, T.T.-Y.; Perry, B.W.; Castoe, T.A.; Rambaut, A.; Robertson, D.L. Evolutionary Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 Sarbecovirus Lineage Responsible for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, J.; Yu, J. Evolutionary Analyses of Emerging GII.2[P16] and GII.4 Sydney [P16] Noroviruses. Virus Evol. 2022, 8, veac030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, K.; Matsushima, Y.; Nagasawa, K.; Motoya, T.; Ryo, A.; Kuroda, M.; Katayama, K.; Kimura, H. Molecular Evolutionary Analyses of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Region in Norovirus Genogroup II. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoya, T.; Nagasawa, K.; Matsushima, Y.; Nagata, N.; Ryo, A.; Sekizuka, T.; Yamashita, A.; Kuroda, M.; Morita, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; et al. Molecular Evolution of the VP1 Gene in Human Norovirus GII.4 Variants in 1974–2015. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Yoshizumi, S.; Kogawa, S.; Takahashi, T.; Ueki, Y.; Shinohara, M.; Mizukoshi, F.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Suzuki, R.; et al. Molecular Evolution of the Capsid Gene in Norovirus Genogroup I. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick Gupta, A.; Mandal, S.; Mandal, S.; Chakrabarti, J. Immune Escape Facilitation by Mutations of Epitope Residues in RdRp of SARS-CoV-2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 3542–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verardi, R.; Lindesmith, L.C.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Gorman, J.; Chuang, G.-Y.; Edwards, C.E.; Brewer-Jensen, P.D.; Mallory, M.L.; Ou, L.; Schön, A.; et al. Disulfide Stabilization of Human Norovirus GI.1 Virus-like Particles Focuses Immune Response toward Blockade Epitopes. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, I.; Ghezzi, S.; Alberti, S.; Poli, G.; Vicenzi, E. Origin and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2023, 138, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.M.; Altfeld, M.; Yu, X.G.; O’Sullivan, K.M.; Lichterfeld, M.; Le Gall, S.; John, M.; Mothe, B.R.; Lee, P.K.; Kalife, E.T.; et al. Selection, Transmission, and Reversion of an Antigen-Processing Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Escape Mutation in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Infection. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 7069–7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillay-Véliz, C.P.; Carvajal, J.J.; Avellaneda, A.M.; Escobar, D.; Covián, C.; Kalergis, A.M.; Lay, M.K. Human Norovirus Proteins: Implications in the Replicative Cycle, Pathogenesis, and the Host Immune Response. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, R.A.; Hyde, J.; Mackenzie, J.M.; Hansman, G.S.; Oka, T.; Takeda, N.; White, P.A. Comparison of the Replication Properties of Murine and Human Calicivirus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases. Virus Genes 2011, 42, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Recommended Health-Based Limits in Ocupational Exposure to Heavy Metals. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 1980, 647, 1–116. [Google Scholar]

| Year | <2000 | 2001–2005 | 2006–2010 | 2011–2015 | 2016–2020 | 2021–2025 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | ||||||||

| GI.3[P3] | 8(21.6) | 42(32.3) | 7(10) | 55(24.8) | 111(34.4) | 3(6.2) | 226(27.2) | |

| GI.3[P13] | 2(5.4) | 32(24.6) | 5(7.1) | 21(9.5) | 96(29.5) | 24(50) | 180(21.1) | |

| GI.3[P10] | 2(5.4) | 0 | 4(5.7) | 3(1.3) | 6(1.8) | 3(6.2) | 18(2.2) | |

| GI.3[P14] | 1(2.7) | 0 | 0 | 3(1.3) | 0 | 0 | 4(0.5) | |

| GI.3[PNA] | 0 | 2(1.5) | 0 | 1(0.4) | 0 | 0 | 3(0.4) | |

| GI.3 * | 24(64.8) | 54(41.5) | 54(77.1) | 138(62.4) | 112(34.4) | 18(37.5) | 400(48.1) | |

| Total | 37(100) | 130(100) | 70(100) | 221(100) | 325(100) | 48(100) | 831(100) | |

| Region | Nucleotide Evolutionary Rate (10-3 Substitutions/Site/Year) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| All RdRp gene | 2.25 (1.75, 2.79) | 83 (100) |

| All GI.3 VP1 gene | 2.64 (1.97, 3.36) | 154 (100) |

| GI.3[P3] RdRp gene | 5.26 (4.03, 6.72) | 38 (45.7) |

| GI.3[P10] RdRp gene | 2.61 (1.93, 3.36) | 5 (6.0) |

| GI.3[P13] RdRp gene | 3.04 (1.83, 4.53) | 38 (45.7) |

| GI.3[P14] RdRp gene | - | 2 (2.4) |

| GI.3[P3] VP1 gene | 3.76 (1.99, 5.59) | 83 (53.9) |

| GI.3[P10] VP1 gene | 0.12 (<0.01, 0.85) | 5 (3.2) |

| GI.3[P13] VP1 gene | 2.75 (2.41, 3.11) | 63 (40.9) |

| GI.3[P14] VP1 gene | 3.60 (3.19, 4.27) | 3 (1.9) |

| Genotype | Km (GTP), Michaelis-Menten Model(mM) at 30 °C | Vmax |

|---|---|---|

| GI.3[P3] | 0.176 | 50,817 |

| GI.3[P10] | 0.198 | 32,704 |

| GI.3[P13] | 0.092 | 48,941 |

| GI.3[P14] | 0.273 | 30,541 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lu, Q.; Du, H.; Jiang, X.; Zeng, B.; Li, T.; Dai, Y.-C. Superior RdRp Function Drives the Dominance of Prevalent GI.3 Norovirus Lineages. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010011

Lu Q, Du H, Jiang X, Zeng B, Li T, Dai Y-C. Superior RdRp Function Drives the Dominance of Prevalent GI.3 Norovirus Lineages. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Qianxin, Huisha Du, Xin Jiang, Bingwen Zeng, Tianhui Li, and Ying-Chun Dai. 2026. "Superior RdRp Function Drives the Dominance of Prevalent GI.3 Norovirus Lineages" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010011

APA StyleLu, Q., Du, H., Jiang, X., Zeng, B., Li, T., & Dai, Y.-C. (2026). Superior RdRp Function Drives the Dominance of Prevalent GI.3 Norovirus Lineages. Microorganisms, 14(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010011