Effects of Effective Microorganism (EM) Inoculation on Co-Composting of Auricularia heimuer Residue with Chicken Manure and Subsequent Maize Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

- EM inoculation significantly accelerates the composting process and enhances compost quality;

- 5–10% EM treatment yields optimal effects on promoting lignocellulose degradation and nutrient release;

- Application of EM-treated compost significantly increases soil enzyme activity, thereby promoting maize growth and yield formation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Experimental Design

2.1.1. Composting Fermentation Treatment

2.1.2. Pot-Plant Experiments

2.2. Determination Methods

2.2.1. Analysis of Compost and Soil Properties

2.2.2. Analysis of Maize Tissue and Growth Indicators

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Temperature, Moisture Content, and pH During Composting

3.2. Changes in Lignocellulose Content

3.3. Changes in Total Nitrogen, Total Phosphorus, and Total Potassium Content

3.4. Maize Growth Indicators

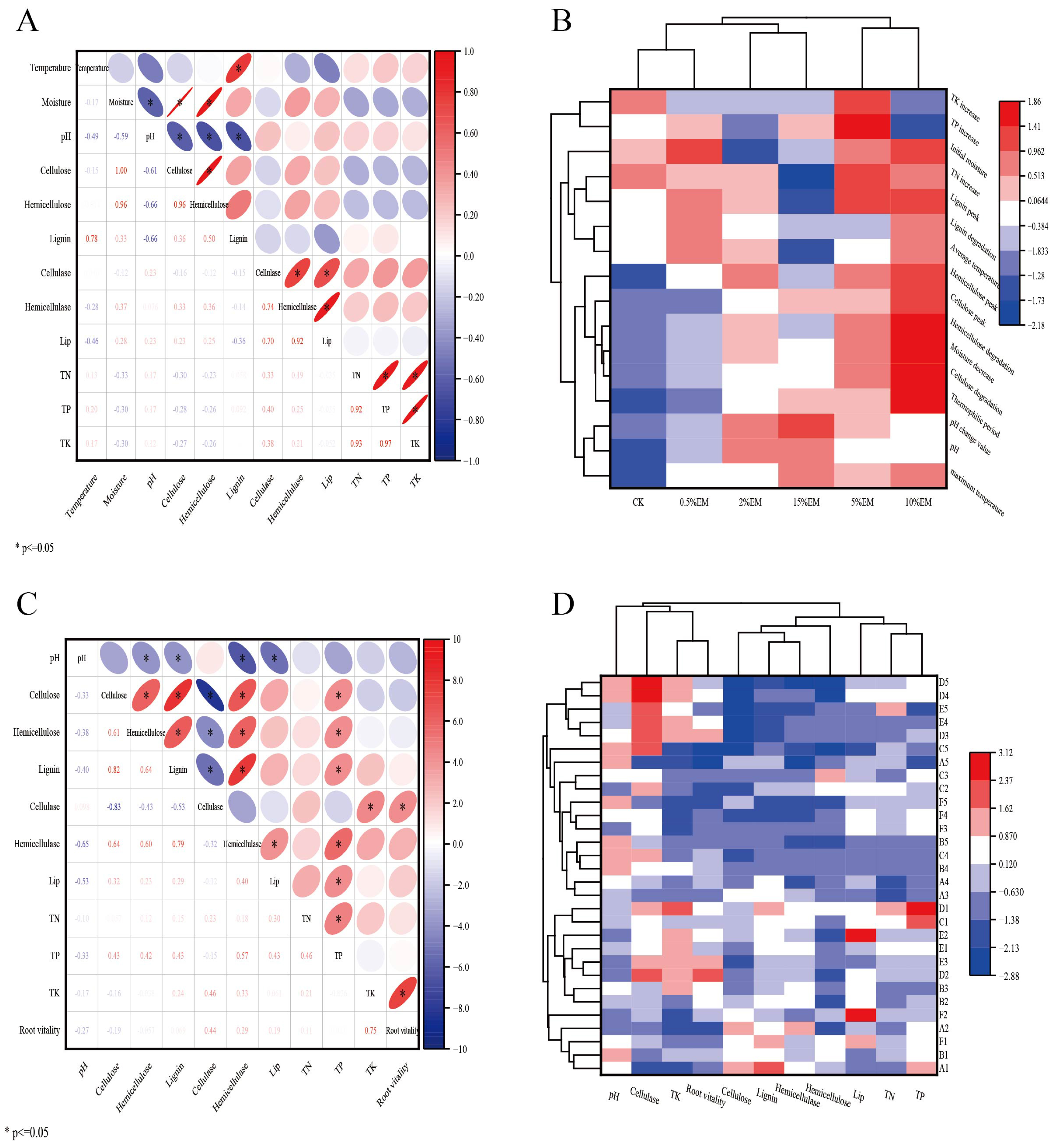

3.5. Correlations Between Substrate Environment, Lignocellulosic Content, Enzyme Activity, and Maize Yield

3.6. Correlation Between Compost and Maize Growth Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of EM on the Composting Cycle

4.1.1. Effect of EM Inoculation on Temperature and Moisture Content

4.1.2. pH Changes and Fermentation Process

4.2. Promotion of Lignocellulose Degradation by EM Inoculation

4.2.1. Degradation of Cellulose and Hemicellulose

4.2.2. Lignin Degradation

4.2.3. Correlation Between Enzyme Activity and Degradation Efficiency

4.3. Effects of EM on Nutrient Retention and Transformation in Compost

4.4. Effects of EM on Maize Yield

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Shang, W.; Zhang, T.; Chang, X.; Wu, Z.; He, Y. Effect of microbial inoculum on composting efficiency in the composting process of spent mushroom substrate and chicken manure. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Kang, M.; Li, R.; Nie, Y. Effects of spent mushroom substrates on the roots, nitrogen accumulation, yield and fruit quality of continuous tomato in greenhouse. Acta. Hortic. Sin. 2025, 52, 2969–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Wang, X.; Cong, C.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Hou, F.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L. Effect of inoculating microorganisms in chicken manure composting with maize straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Yin, Y. Effects of biocompost derived from spent mushroom substrates on soil microbial activity, abundance and diversity in cucumber field. Chin. J. Ecol. 2024, 43, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Sun, W.; Tang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Fang, B.; Liu, P. Research progress in solid organic wastes aerobic fermentation composting technology. Mod. Chem. Ind. 2024, 44, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassine, Y.N.; Naim, L.; El Sebaaly, Z.; Abou Fayssal, S.; Alsanad, M.A.; Yordanova, M.H. Nano urea effects on Pleurotus ostreatus nutritional value depending on the dose and timing of application. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Awasthi, S.K.; Liu, T.; Duan, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Z.; Pandey, A.; Awasthi, M.K. Effects of microbial culture and chicken manure biochar on compost maturity and greenhouse gas emissions during chicken manure composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 121908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Amanze, C.; Yu, R.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Shen, L.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zeng, W. Insight into the microbial mechanisms for the improvement of composting efficiency driven by Aneurinibacillus sp. LD3. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Jin, H.; Dong, Y. Increased enzyme activities and fungal degraders by Gloeophyllum trabeum inoculation improve lignocellulose degradation efficiency during manure–straw composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 337, 125427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Huqail, A.A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Eid, E.M.; Taher, M.A.; Adelodun, B.; Abou Fayssal, S.; Mioč, B.; Držaić, V.; Goala, M.; et al. Sustainable valorization of four types of fruit Peel waste for biogas recovery and use of digestate for radish (Raphanus sativus L. Cv. Pusa Himani) cultivation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Saha, T.N.; Arora, A.; Shah, R.; Nain, L. Efficient microorganism compost benefits plant growth and improves soil health in calendula and marigold. Hortic. Plant J. 2017, 3, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wei, J.; Shao, X.; Yan, X.; Liu, K. Effective microorganisms input efficiently improves the vegetation and microbial community of degraded alpine grassland. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1330149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriti, M.; Scarafoni, A.; Pierce, S.; Castorina, G.; Vitalini, S. Soil application of effective microorganisms (EM) maintains leaf photosynthetic efficiency, increases seed yield and quality traits of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants grown on different substrates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, A.; Pineda Herrera, J.C.; Vanegas, J.; Soler, J.; Peña, J.; Pérez, P.; Pinilla, J. Biochar, Compost, and Effective Microorganisms: Evaluating the Recovery of Post–Clay Mining Soil. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brangarí, A.C.; Lyonnard, B.; Rousk, J. Soil depth and tillage can characterize the soil microbial responses to drying–rewetting. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2022, 173, 108806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Xia, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Shao, P. Biochar and effective microorganisms promote Sesbania cannabina growth and soil quality in the coastal saline–alkali soil of the Yellow River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Gyushi, M.A.H.; Hemida, K.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Abd El-Mageed, S.A.; Abdalla, H.; AbuQamar, S.F.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; Abdelkhalik, A. Coapplication of effective microorganisms and nanomagnesium boosts the agronomic, physio–biochemical, osmolytes, and antioxidants defenses against salt stress in Ipomoea batatas. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 883274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwica, K.; Gałęzewski, L.; Wilczewski, E.; Kubiak, W. Reduced Tillage, Application of Straw and Effective Microorganisms as Factors of Sustainable Agrotechnology in Winter Wheat Monoculture. Agronomy 2024, 14, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, N.B.; Abdel-Salam, S.A.M. An innovative, sustainable, and environmentally friendly approach for wheat drought tolerance using vermicompost and effective microorganisms: Upregulating the antioxidant defense machinery, glyoxalase system, and osmotic regulatory substances. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasia, J.; Poudel, B.; Mandal, T.; Acharya, N.; Ghimirey, V. Effect of micronutrients, rhizobium, salicylic acid, and effective microorganisms in plant growth and yield characteristics of green gram [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] in Rupandehi, Nepal. Heliyon 2024, 10, 26821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, N.B. Effective microorganisms modify protein and polyamine pools in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants grown under saline conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 190, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein, T.J.; Erickson, G.E.; Berger, L.L. Maize is a Critically Important Source of Food, Feed, Energy and Forage in the USA. Field Crops Res. 2013, 153, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, E.; Matsi, T.; Barbayiannis, N.; Lithourgidis, A. Liquid Cattle Manure Effect on Corn Yield and Nutrients’ Uptake and Soil Fertility, in Comparison to the Common and Recommended Inorganic Fertilization. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 1914–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Feng, Z.; Yan, S.; Zhang, J.; Song, H.; Zou, Y.; Jin, D. The Effect of the Application of Chemical Fertilizer and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Maize Yield and Soil Microbiota in Saline Agricultural Soil. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.X.; Chen, Q.J.; Qin, Y.; Yang, Y.R.; Yang, Q.Z.; Wang, Y.X.; Cheng, Z.A.; Cao, N.; Zhang, G.Q. Succession of the microbial communities and function prediction during short–term peach sawdust–based composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 332, 125079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, D.; Chu, S.; Zhi, Y.; Hayat, K.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Hui, N.; Zhou, P. Streptomyces griseorubens JSD–1 promotes rice straw composting efficiency in industrial–scale fermenter: Evaluation of change in physicochemical properties and microbial community. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 321, 124465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, H.; Yao, T.; Su, M.; Ran, F.; Han, B.; Li, J.; Lan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Microbial inoculation influences bacterial community succession and physicochemical characteristics during pig manure composting with corn straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.P.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Moral, R. Composting of animal manures and chemical criteria for compost maturity assessment. A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 5444–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, K.; Khandeshwar, S.; Waghmare, C.; Mehboob, H.; Gupta, T.; Shrikhande, A.N.; Abbas, M. Experimental Evaluation of Industrial Mushroom Waste Substrate Using Hybrid Mechanism of Vermicomposting and Effective Microorganisms. Materials 2022, 15, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.R.; Guo, Y.X.; Wang, Q.Y.; Hu, B.Y.; Tian, S.Y.; Yang, Q.Z.; Cheng, Z.A.; Chen, Q.J.; Zhang, G.Q. Impacts of composting duration on physicochemical properties and microbial communities during short term composting for the substrate for oyster mushrooms. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 847, 157673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wei, Y.; Kou, J.; Han, Z.; Shi, Q.; Liu, L.; Sun, Z. Improve spent mushroom substrate decomposition, bacterial community and mature compost quality by adding cellulase during composting. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 299, 126928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Yin, R.; Cheng, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Gao, X.; Li, G.; Nghiem, L.; Luo, W. Bacterial dynamics for gaseous emission and humification in bio–augmented composting of kitchen waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, X.; Yu, Y.; Teng, Z.; Chen, J. Enhanced lignocellulose degradation and composts fertility of cattle manure and wheat straw composting by Bacillus inoculation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Zhang, H.; Fu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Li, R.; Zhai, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, L. Effects of four additives in pig manure composting on greenhouse gas emission reduction and bacterial community change. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 121896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Awasthi, M.K.; Jiang, Y.; Li, R.; Ren, X.; Zhao, J.; Shen, F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z. Evaluation of medical stone amendment for the reduction of nitrogen loss and bioavailability of heavy metals during pig manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 220, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Z.; Liu, X.; Sun, L.; He, X.; Wu, Z. Effects of two types nitrogen sources on humification processes and phosphorus dynamics during the aerobic composting of spent mushroom substrate. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, S.; Duan, P.; Lin, F. Effects of microalgal fertilizer on physical and chemical properties of saline soils and maize yield in tumochuan plain. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 45, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, Y.; Yan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Tian, F.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z. Insight into the microbial mechanisms for the improvement of spent mushroom substrate composting efficiency driven by phosphate–solubilizing Bacillus subtilis. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Li, M.; Li, Q. A compost–derived thermophilic microbial consortium enhances the humification process and alters the microbial diversity during composting. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 243, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zheng, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Dong, S.; Hu, X. The impact of microbial inoculants on large–scale composting of straw and manure under natural low–temperature conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 400, 130696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.W.; Guo, Y.X.; Chen, Q.J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.Y.; Yang, Y.R.; Zhang, G.Q. Metagenomic insights into the lignocellulose degradation mechanism during short–term composting of peach sawdust: Core microbial community and carbohydrate–active enzyme profile analysis. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Širić, I.; Eid, E.M.; Taher, M.A.; El-Morsy, M.H.E.; Osman, H.E.M.; Kumar, P.; Adelodun, B.; Abou Fayssal, S.; Mioč, B.; Andabaka, Ž.; et al. Combined use of spent mushroom substrate biochar and PGPR improves growth, yield, and biochemical response of cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis): A preliminary study on greenhouse cultivation. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhu, Y.; Kan, Z.; Li, B.; Cao, Y.; Jin, H. Effects of two–stage microbial inoculation on organic carbon turnover and fungal community succession during co–composting of cattle manure and rice straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Qian, K.; Feng, Y.; Ao, J.; Zhai, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Yu, H. Effects of Auricularia heimuer Residue Amendment on Soil Quality, Microbial Communities, and Maize Growth in the Black Soil Region of Northeast China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Ji, L.; Wu, G.; Li, B.; Cheng, L.; Long, M.; Deng, W.; Zou, L. The Influence of Effective Microorganisms on Microbes and Nutrients in Kiwifruit Planting Soil. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergensen, R.G. Phospholipid fatty acids in soil—Drawbacks and future prospects. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2022, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, D.; Li, B.; Jin, H.; Dong, Y. Enhanced turnover of phenolic precursors by Gloeophyllum trabeum pretreatment promotes humic substance formation during co–composting of pig manure and wheat straw. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, Q.; Li, Y.; Wei, Z. Effect of thermo–tolerant actinomycetes inoculation on cellulose degradation and the formation of humic substances during composting. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, A.; Bajwa, R. Field evaluation of effective microorganisms (EM) application for growth, nodulation, and nutrition of mung bean. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2011, 35, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, W.; Piao, R.; Cui, Z.; Zhao, H. Degradation of lignocelluloses in straw using AC–1, a thermophilic composite microbial system. PeerJ 2021, 9, 12364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.T. Consortia–based microbial inoculants for sustaining agricultural activities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 176, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, G. Wheat straw: An inefficient substrate for rapid natural lignocellulosic composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 209, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Fan, Y.; Lee, C.T.; Klemeš, J.J.; Chua, L.S.; Sarmidi, M.R.; Leow, C.W. Evaluation of Effective Microorganisms on home scale organic waste composting. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 216, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Jin, N.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Meng, X.; Xie, Y.; Wu, Y.; Luo, S.; Lyu, J.; Yu, J. Changes in the microbial structure of the root soil and the yield of Chinese baby cabbage by chemical fertilizer reduction with bio–organic fertilizer application. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01215-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Tao, X.; Zhang, L.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, J. Inoculation of phosphate–solubilizing bacteria (Bacillus) regulates microbial interaction to improve phosphorus fractions mobilization during kitchen waste composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 340, 125714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talaat, N.B. Effective microorganisms: An innovative tool for inducing common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) salt–tolerance by regulating photosynthetic rate and endogenous phytohormones production. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 250, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menino, R.; Felizes, F.; Castelo–Branco, M.A.; Fareleira, P.; Moreira, O.; Nunes, R.; Murta, D. Agricultural value of Black Soldier Fly larvae frass as organic fertilizer on ryegrass. Heliyon 2021, 7, 05855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, F.M.; Sheng, J.L.; Li, G.; Ma, J.J.; Wang, X.Z.; Jiang, C.L.; Zhang, Z.J. Black soldier fly larvae vermicompost alters soil biochemistry and bacterial community composition. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 4315–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Yu, X.; Liang, J.; Mao, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, X. A full recycling chain of food waste with straw addition mediated by black soldier fly larvae: Focus on fresh frass quality, secondary composting, and its fertilizing effect on maize. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 885, 163386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.Z.; Yu, Y.L.; Yang, Z.B.; Xu, X.X.; Lv, G.C.; Xu, C.L.; Wang, G.Y.; Qi, X.; Li, T.; Man, Y.B.; et al. Synergistic improvement of humus formation in compost residue by fenton–like and effective microorganism composite agents. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 400, 130703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yi, L.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.; Guo, F. Effects of different fertilizer enhancers on the growth and development of pepper and rhizosphere soil nutrient in high altitude region. China Cucurbits Veg. 2025, 38, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Xia, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Peng, L. Effects of biochar and em application on growth and photosynthetic characteristics of sesba–nia cannabina in saline–alkali soil of the yellow river delta, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 31, 3101–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, N.; Dennis, M.W.; John, M.M.; Omwoyo, O.; Dative, M.; Alice, A.; Martins, O.; Sheila, A.O.; William, A.; John, V.O. Compatibility of Rhizobium inoculant and water hyacinth compost formulations in Rosecoco bean and consequences on Aphis fabae and Colletotrichum lindemuthianum infestations. Appl Soil Ecol. 2014, 76, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Khan, M.H.; Yuan, Z.; Hussain, S.; Cao, H.; Liu, Y. Response of soil microbiome structure and its network profiles to four soil amendments in monocropping strawberry greenhouse. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 0245180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, H.; Wei, W.; Cui, N.; Liang, H. Effect and mechanism of effective microorganisms agents on the dynamics changes of antibiotic resistance genes in soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, H.; Ma, Q.; Mu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhang, F.; Xie, H. Exploring the mitigation effect of microbial inoculants on the continuous cropping obstacle of capsicum. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Jin, C.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, J.; Leghari, S.J.; Pan, H. Relationship between pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) root morphology, inter–root soil bacterial community structure and diversity under water–air intercropping conditions. Planta 2023, 257, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Ao, J.; Qian, K.; Wang, Y.; Ma, M.; Sun, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; et al. Effects of Effective Microorganism (EM) Inoculation on Co-Composting of Auricularia heimuer Residue with Chicken Manure and Subsequent Maize Growth. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010106

Feng Y, Zhai Y, Ao J, Qian K, Wang Y, Ma M, Sun P, Li Y, Zhang B, Li X, et al. Effects of Effective Microorganism (EM) Inoculation on Co-Composting of Auricularia heimuer Residue with Chicken Manure and Subsequent Maize Growth. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Yuting, Yinzhen Zhai, Jiangyan Ao, Keqing Qian, Ying Wang, Miaomiao Ma, Peinan Sun, Yu Li, Bo Zhang, Xiao Li, and et al. 2026. "Effects of Effective Microorganism (EM) Inoculation on Co-Composting of Auricularia heimuer Residue with Chicken Manure and Subsequent Maize Growth" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010106

APA StyleFeng, Y., Zhai, Y., Ao, J., Qian, K., Wang, Y., Ma, M., Sun, P., Li, Y., Zhang, B., Li, X., & Yu, H. (2026). Effects of Effective Microorganism (EM) Inoculation on Co-Composting of Auricularia heimuer Residue with Chicken Manure and Subsequent Maize Growth. Microorganisms, 14(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010106