Abstract

Giardia lamblia is a flagellated protozoan and the etiological agent of giardiasis, a leading cause of epidemic and sporadic diarrhoea globally. The clinical and public health relevance of giardiasis underscores the need for robust methodologies to investigate and manage this pathogen. This study reviews the main methodologies described in the literature for studying the life cycle of G. lamblia, focusing on isolation, purification, axenization, excystation, and encystation. A systematic literature review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) statement. Searches were performed in MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science Core Collection databases. A total of 43 studies were included, revealing 58 methods for isolation and purification, 7 for excystation, 2 for axenization, and 5 for encystation. Isolation and purification methods exhibited significant variability, often involving two phases: an initial separation (e.g., filtration and centrifugation) followed by purification using a density gradient for faecal samples or immunomagnetic separation for water samples. Method effectiveness differed depending on the sample source and type, limiting comparability across studies. In contrast, methods used for other life cycle stages were more consistent. These findings underscore the need for standardised methodologies to enhance the reproducibility and reliability of research outcomes in this field.

1. Introduction

The etiological agent of giardiasis, Giardia lamblia (G. lamblia), is a flagellated protozoan parasite that is a major cause of both epidemic and sporadic diarrhoea worldwide [1]. Giardiasis is prevalent and has occurred in outbreaks across the globe since the 1970s. It was listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a neglected tropical disease, but it was later removed from the list, reflecting ongoing debate over its global burden and prioritisation [2]. The life cycle of G. lamblia comprises two distinct stages adapted to different environmental conditions: an infectious cyst stage and a proliferating trophozoite stage [1,3,4]. The infection is mainly transmitted via the faecal–oral route, resulting from the ingestion of cysts through the consumption of water or food contaminated with faecal matter [1,4]. After ingestion, excystation occurs in the duodenum due to exposure to gastric acid, bile, and pancreatic proteases, resulting in the release of two motile trophozoites per cyst. Trophozoites primarily inhabit the proximal small intestine (duodenum and jejunum) and attach to enterocytes via the ventral disc. During the trophozoite stage, clinical symptoms appear as trophozoites replicate by binary fission into numerous trophozoites. Detached trophozoites pass through the intestinal tract, where encystation is initiated in the small intestine and completed in the colon [1,4]. Cysts are excreted in the faeces and are immediately infectious, remaining viable in the environment until ingestion by a new host, consequently restarting the cycle all over again [3,4]. Axenic in vitro systems enable the study of parasite biochemistry and differentiation mechanisms throughout the parasite life cycle [2]. Excystation and encystation are differentiation processes that occur in response to environmental conditions perceived by the parasite in the host. Both processes can be induced by simulating the conditions found in the human gastrointestinal tract [3]. Excystation and encystation are targets for chemotherapeutic and immunotherapeutic intervention [2]. The clinical and public health burden of giardiasis underscores the need for robust methods to study and manage this pathogen. Diverse techniques have been developed and refined over the years to isolate G. lamblia cysts from environmental samples, maintain axenic cultures under laboratory conditions, and understand the mechanisms underlying encystation and excystation. Despite advances in this field, many experimental protocols remain technically complex and poorly standardised. For example, Rice and Schaefer (1981) reported in vitro excystation yields averaging 87% and 70% for cysts from symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, respectively [5]. In contrast, Boucher and Gillin (1990) observed lower excystation efficiencies, ranging from 10% to 38%, depending on the type of protease used and the origin of the cysts [6]. Furthermore, in vitro encystation protocols are also often inconsistent, as, for example, Fink et al. (2020) achieved only approximately 10% cyst formation using strain GS in an optimised bile–lactic acid medium [7]. Even well-established environmental isolation protocols, such as EPA Method 1623, produce highly variable recovery rates, ranging from less than 1% to over 50%, largely due to differences in sample turbidity and particulate content [8]. The aim of this systematic review was to identify the main methods cited in the literature used throughout the G. lamblia life cycle, including isolation, purification, axenization, excystation, and encystation.

2. Materials and Methods

The current systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) statement, which aims to improve the quality and transparency of systematic review reporting [9]. The protocol for this systematic review was registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) and is available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4FP8Y (accessed on 17 July 2025). To formulate the research question and structure the literature search, the SPIDER tool, adapted from Cooke et al. [10], was employed. These frameworks help ensure methodological rigour and comprehensive coverage of the relevant literature. The research question guiding this review was: “What are the predominant methodologies employed for the isolation, purification, excystation and encystation of G. lamblia?” (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of employed SPIDER tool adapted from Cooke et al. [10].

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted across the MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science Core Collection databases using the following search equation: “(“axenization” OR “isolation” OR “excystation” OR “encystation” OR “purification”) AND (“method”) AND (“giardia”)”. In the ScienceDirect and Web of Science databases, the search was based on title, abstract, or author-specified keywords. In MEDLINE, the available MeSH terms were used. The databases were last accessed on 24 June 2025.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies eligible for inclusion were research articles written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish. These articles were specifically required to assess methods to evaluate the processes of encystation, excystation, isolation, purification, and axenization of G. lamblia. Studies lacking explicit specifications of the methods employed were excluded, as were reviews and meta-analyses. No restrictions were imposed regarding the timeframe of the search.

2.3. Quality Assessment

A critical appraisal was used for assessing the quality of the studies included in the review, through the development of a checklist adapted from McConn et al. [11]. The checklist included the following quality assessment parameters: clearly specified criteria for sample selection and collection; mention of the source of the samples used; use of controls to validate the experimental procedures; explanation of the methods used and their adaptability to standard laboratory conditions; adequate description of statistics for study replication; assessment of G. lamblia viability and functionality; and appropriate discussion of the results obtained. Eight parameters, in the form of questions, were scored on a binary scale as “yes” (criterion met), “no” (criterion not met), or “not applicable/not sure” (Table 2). The total number of “yes” was then summed to assign a quality based on the following scale: 1–2 “yes” = unsatisfactory; 3–4 “yes” = satisfactory; 5–6 “yes” = good; and 7–8 “yes” = excellent.

Table 2.

Questions used as quality assessment criteria for article evaluation.

3. Results

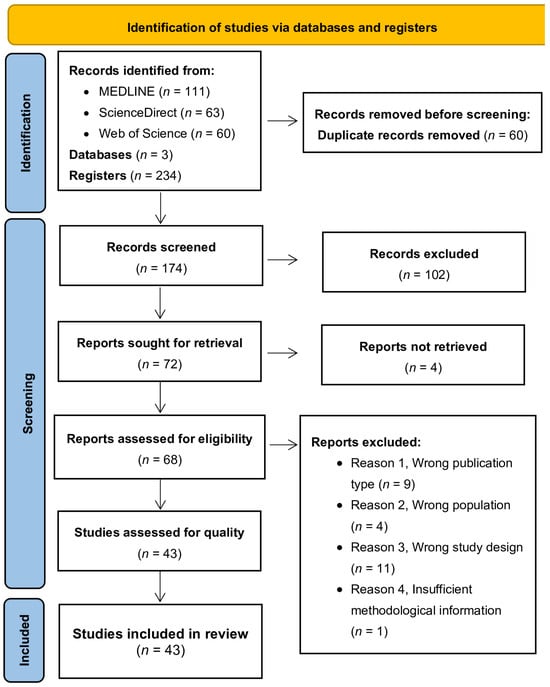

The electronic search yielded a total of 234 articles, with 111 entries retrieved from MEDLINE, 63 from ScienceDirect, and 60 from Web of Science (Figure 1). These sets of records were downloaded from each respective database and then integrated into the Rayyan platform [12]. This consolidation served the dual purpose of removing duplicate records and facilitating the retrieval of pertinent articles. Following the elimination of duplicates, a total of 174 studies remained for further evaluation. The titles and abstracts of all identified studies were independently examined by two reviewers, according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus discussions. Given the low number of conflicts and their effective resolution, the involvement of a third reviewer was deemed unnecessary. Records that were evidently irrelevant were excluded. In cases where the abstract and/or title did not provide sufficient information to comply with the inclusion criteria, the full text of the report was obtained for thorough evaluation. Consequently, 68 studies were selected for full-text reading, and these were independently assessed by the same two reviewers. Articles that did not meet all inclusion criteria after the full-text assessment (n = 25) were excluded from further examination. Figure 1 illustrates and summarises the complete study selection process.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the selection procedure adapted from the PRISMA 2020 statement [9].

3.1. Quality Assessment Results

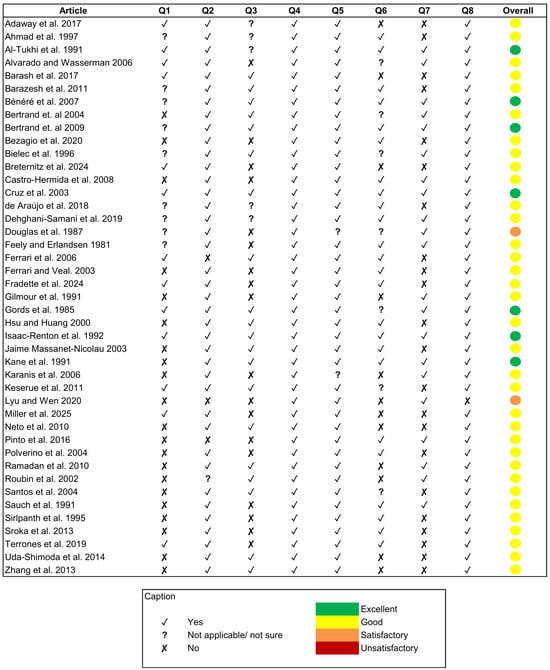

To minimise the risk of bias, an assessment of the quality of the articles included in the review was conducted through the development of an 8-question checklist. The studies included in the review (n = 43) were evaluated based on the question checklist described above. Based on the number of criteria met (“yes” responses), the studies were classified into quality categories (Figure 2). Of the total number of articles included in the review, 79% were classified as good (5–6 criteria met), 16.3% as excellent (7–8 criteria met), and 4.7% as satisfactory (3–4 criteria met). No articles were classified as unsatisfactory (1–2 criteria met), and therefore, no articles were excluded from the review.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of the reviewed articles [8,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54] considering the questions (Q1 to Q8) formulated in Table 2.

3.2. Characterisation of Included Studies

The 43 included studies used a wide range of sample types, including water samples (n = 23), human faecal samples (n = 16), animal faecal samples (n = 9), commercial samples (n = 11), reference isolates (ATCC 30888, ATCC 30957, and ATCC 50803; n = 7), laboratory strains (n = 2), and others (rectal swabs, intestinal scrapings, and duodenal fluid; n = 4). The water samples in the included studies were collected from various sources (Table 3). Most of the reviewed studies were classified as experimental.

Table 3.

Water sample sources in included studies.

The present systematic review identified a variety of methods used for the isolation, purification, excystation, axenization, and encystation of G. lamblia. Many authors often use the terms “isolation” and “purification” interchangeably when referring to methods for obtaining G. lamblia cysts or trophozoites. This underscores the very closely related nature of both processes, where isolation typically refers to the initial separation of the organism from its environment, e.g., using a filtration method, and purification involves subsequent steps to further clean the sample, e.g., the sucrose flotation method. To reflect this common practice and ensure comprehensive coverage, both isolation and purification methods were compiled into the same table (Table 4).

Table 4.

Methods for isolation and purification of G. lamblia.

To enhance the interpretation of the methodologies retrieved for the isolation and purification of G. lamblia cysts or trophozoites, the methods were organised chronologically and grouped into distinct categories according to the principle of the technique employed, when identifiable. The following categories were established:

- Immunomagnetic Separation (IMS): Uses magnetic beads coated with antibodies for targeted separation.

- Density Gradient: Involves the use of continuous or discontinuous gradients composed of one or more solutions with varying densities (e.g., sucrose, Percoll) to separate cysts based on buoyancy.

- Flotation: Use of a single high-density solution (e.g., zinc sulfate) to float the cysts while denser debris settles.

- Coagulation–flocullation: Employment of chemical coagulants (e.g., aluminium sulfate, calcium chloride) to aggregate suspended particles and cysts into flocs.

- Sedimentation: Natural or centrifugation-assisted settling of particles based on the difference in sizes or densities.

- Filtration: A physical separation using mesh, gauze, membranes, or columns, applied mainly to water samples.

- Fluorescence-based Immunoseparation: Uses fluorescently labelled antibodies to specifically identify and isolate cysts.

- Mechanical Purification: Procedures involving physical disruption, temperature alternation, or osmotic shock, applied mainly for the selective removal of trophozoites and debris.

3.3. Methods for Isolation and Purification of G. lamblia

A total of 58 methods were identified for the isolation and purification of G. lamblia and were classified into 15 different groups (Table 4). The initial separation of the organism from the rest of the sample, which often contains large amounts of debris and contaminants, was primarily achieved through a combination of filtration, low-speed centrifugation, and multiple washing steps with solutions such as Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or distilled water. For further purification of the sample, the two most cited methods were density gradients and immunomagnetic separation (IMS).

Density gradient centrifugation or flotation with sucrose or Percoll® solutions, with densities ranging between 1.10 and 1.275 g/mL, was commonly employed for faecal samples. Polverino et al. compared three techniques for the isolation and purification of G. lamblia cysts and concluded that techniques two (sucrose flotation) and three (a combination of centrifugation and sucrose flotation) left the least amount of debris in the purified cyst suspension [45]. Terrones et al. compared four techniques for the isolation and purification of G. lamblia cysts and concluded that a two-phase sucrose gradient was most effective [52].

IMS was also quite common in the cited studies, particularly when the sample being analysed was from a water source or when it was intended for further deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction. IMS purification step involves the selective separation of Giardia spp. cysts with magnetic microspheres covered with purified antibodies against the cysts. The bead–organism complex undergoes a dissociation step, usually by either acid or heat dissociation [43,44]. Pinto et al. compared two dissociation procedures (acid and heat) in the IMS method and concluded that acid dissociation was more efficient for Giardia spp. cysts [44]. Neto et al. compared calcium carbonate flocculation and membrane filtration, followed or not by an IMS step, and concluded that higher concentrations of cysts were detected when IMS was employed for sample purification [43]. Hsu and Huang compared two purification methods, the Percoll®–sucrose density gradient (ICR protozoan method) and IMS (Method 1623) and found that the average recovery efficiency for Giardia spp. with Method 1623 was 48.0% greater than that with the ICR protozoan method [36]. In some studies, sucrose gradient flotation was also combined with IMS, as it allows for detailed analysis of the G. lamblia genome in clinical stool samples [55].

3.4. Methods for the Excystation of G. lamblia

For the excystation of G. lamblia, seven methods were identified, as presented in Table 5. In the reviewed studies, excystation was generally performed in two phases: an initial low-pH induction phase using acid solutions (pH ≤ 2.0) and a subsequent excystment phase. The first phase was employed in nearly all cited studies and comprised incubating cysts with aqueous hydrogen chloride (HCl) or a pepsin–acid solution for periods of 5–120 min at 37 °C. The second phase exhibited variation in the cited methods. Some protocols use enzymes such as trypsin dissolved in Tyrode solution or cysteine HCl/ascorbic acid mixtures in HBSS to facilitate excystment, while others neutralise the acid solution with sodium bicarbonate before resuspending the cysts in fresh culture medium [26,29,37,39]. Moreover, the excystment phase often involves specific incubation conditions, such as maintaining the cysts in an inverted position at 37 °C and using various growth media (TYI-S-33 or HSP-3) with a pH ranging from 7.0 to 7.8 [16,29].

Table 5.

Methods for excystation of G. lamblia.

3.5. Methods for the Axenization of G. lamblia

For the axenization of G. lamblia, two methods were identified, as presented in Table 6. Most cited studies involved incubating trophozoites at 37 °C with Keisters’ modified TYI-S-33 medium, using different concentrations and combinations of antimicrobials (such as penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B) to prevent bacterial and fungal contamination [56]. The culture medium commonly has an alkaline pH ranging from 7.0 to 7.2 and is often supplemented with bile salts and bovine serum.

Table 6.

Methods for the axenization of G. lamblia trophozoites.

3.6. Methods for the Encystation of G. lamblia

For the encystation of G. lamblia, five methods were identified, as presented in Table 7. In the reviewed studies, encystation was induced using filter-sterilised TYI-S-33 media supplemented with different concentrations of bovine bile, adjusted to pH 7.8. In the method used by Bielec et al., lactic acid was also included in the encystation medium, as this compound has been shown to stimulate encystation [35]. The inclusion of antimicrobials in the encystation medium was optional.

Table 7.

Methods for the encystation of G. lamblia.

4. Discussion

Among the methods identified for the isolation and purification of G. lamblia, density gradient using sucrose or Percoll® and IMS were the most frequently cited. The principle of faecal flotation is based on a gradient produced by the density difference between the solution used and the target sample (parasitic elements). Sucrose or Percoll® solutions are denser than parasitic elements, enabling their isolation at the surface. Factors such as the quantity of examined material, dilution factor used, whether centrifugation is performed, the length of time allowed for flotation, and the type and specific gravity of the flotation solution used can influence the ability to detect parasites and the yield of the flotation process [57].

IMS has demonstrated higher recovery rates, particularly in water samples or when followed by molecular techniques. Nevertheless, its performance is sensitive to sample turbidity, and the method becomes less efficient as turbidity increases, as shown by Ferrari and Veal [32]. While Method 1623, which incorporates IMS, is often cited for its higher cyst recovery efficiency, its high cost and reliance on specific reagents poses a challenge for its application in low-resource settings [36]. Additionally, several factors such as sediment volume, sample volume and turbidity, magnetic material concentration, antibody type, reagents and conditions used, and pH, may affect the efficiency of the IMS method [43,44,55].

Excystation methods identified in this review generally mimic the natural process that occurs within the digestive system of an infected host and usually involves two steps: an acid induction phase at low pH (≤2.0) and a neutralisation step and incubation in nutrient-rich medium. Gastric acid (pH 1.5–3.5) initiates excystation by creating an acidic environment similar to laboratory-induced conditions (pH ≤ 2.0). Upon passage through the stomach, cysts encounter the neutral pH environment of the small intestine (pH 6.0–7.3), similar to the solutions used in vitro to neutralise acid-induced excystation [58,59]. While these in vitro models provide valuable insights, they may oversimplify the complex physiological context of the host and their excystation yield can differ significantly between protocols, ranging from 30% to over 80%, depending on factors such as cyst maturity, duration of acid exposure, temperature, and composition of the neutralisation medium. On the other hand, in vivo excystation, such as the model used by Isaac-Renton et al. [37], allows the assessment of trophozoite recovery under real physiological conditions that may reflect better the true physiological process. However, these models involve ethical and logistical complexities and may also limit the direct extrapolation of findings to human infections, as they differ from human hosts in terms of physiology, immune response, and gastrointestinal environment. Therefore, while in vitro methods allow greater experimental control and reproducibility, in vivo models remain valuable for establishing biological relevance and understanding host–parasite interactions during excystation.

In the axenization step, most studies used Keister’s modified TYI-S-33 medium supplemented with antimicrobials. Antimicrobial agents such as penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B in axenic cultures are essential for the elimination of bacterial and fungal contaminants, which are common in clinical or environmental isolates. However, the optimal combination and concentration of these agents may vary depending on the source of the sample and the sensitivity of the trophozoites to culture conditions. Such variability highlights the importance of adjusting axenization protocols to the biological context of the isolate and the research goal.

Most cited methods for encystation used TYI-S-33 medium with bovine bile and an alkaline pH (around 7.8), which are essential factors for inducing encystation, as together they simulate the conditions found in the small intestine that trigger cyst formation in vivo [57,58,60]. The inclusion of antimicrobials in the encystation medium was optional, which may be due to the specific aims of the studies, such as the need to replicate the natural conditions of the small intestine where natural interactions can occur between G. lamblia and the gut microbiota. Barash et al. [17] employed an in vivo encystation protocol, in which mice were orally inoculated with trophozoites to study cyst development under physiological conditions. The study demonstrated that local parasite density plays a key role in triggering encystation in vivo, supporting similar findings from in vitro experiments. These observations highlight the value of in vivo models for capturing the physiological complexity of host–parasite interactions that are difficult to replicate under in vitro conditions.

Regarding G. lamblia viability, few studies systematically assessed the integrity and viability of cysts post-purification, excystation, or encystation. Methods such as dye exclusion assays (e.g., trypan blue), fluorogenic vital stains (e.g., resazurin), or molecular viability PCR can be used, but their application was inconsistent across the literature. The presence of non-viable cysts may lead to the misinterpretation of yield and compromise the evaluation of method effectiveness. Hence, performing viability assays is recommended to ensure that isolated cysts remain infectious or metabolically active, particularly if they are to be used for further studies.

Altogether, the findings of this review demonstrate a broad range of methods and highlight significant challenges related to reproducibility, standardisation, and contextual adaptation. Comparative validation studies and the development of clear guidelines are required to support researchers in selecting appropriate, reliable, and resource-appropriate methodologies for working with G. lamblia in laboratory settings.

5. Conclusions

G. lamblia is one of the most common waterborne parasites that infects humans. The cyst stage of this parasite remains viable in the environment until ingestion by a new host and has been extensively identified in various water sources accessed by humans and animals. The present systematic review identified a range of methods used throughout the G. lamblia life cycle, including isolation, purification, axenization, excystation, and encystation. The findings reveal significant variation in the design, complexity, and effectiveness of the currently employed methods.

The isolation and purification of G. lamblia was the step that showed the greatest variability in the methods used. Sucrose gradient flotation and IMS emerged as the most employed methods; however, their yield is greatly dependent on sample characteristics and operational variables, including turbidity, reagent composition, and centrifugation parameters. Moreover, some of the most used and effective protocols, such as Method 1623, have high cost and technical complexity, which may limit their use in low-resource settings and underscore the need for cost-effective alternatives. In such cases, sucrose and Percoll® flotation, or mechanical purification and filtration methods, offer practical and low-cost alternatives when appropriately optimised.

Excystation and encystation methods are designed to attempt to simulate physiological conditions encountered in the host gastrointestinal tract in vitro. Nevertheless, the reproducibility of these methods remains limited, and their success rates vary significantly across studies. In vitro models are often employed and, while practical, they may not fully replicate the complexity of host–parasite infection. Despite the fact of being rarely used, in vivo studies have provided complementary insights into these biological processes.

Axenization methods require the use of antimicrobials to reduce the microbial contamination of samples. However, there is currently no consensus on the optimal composition or concentration of these combinations, and adjustments are often needed based on the source and growth characteristics of the isolate.

Collectively, these findings show the need for the development and adoption of standardised methodologies that are more accessible, adaptable, and cost-effective. Based on the comparative assessment, IMS and density-based flotation methods remain the most promising for isolation and purification; TYI-S-33-based media are standard for axenization and encystation, while excystation protocols require better harmonisation and validation. Future research should prioritise methodological harmonisation, including the establishment of clearly defined benchmarks and the implementation of reproducibility standards. These efforts will enhance the uniformity of G. lamblia research across laboratories and facilitate the establishment of best practices for experimental studies involving this parasite.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., M.S. and A.C.; methodology, S.S. and M.S.; formal analysis, S.S.; data curation, S.S. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and M.S.; visualisation, S.S.; supervision, A.C.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received support and help from FCT/MCTES (LA/P/0008/2020 DOI 10.54499/LA/P/0008/2020, UIDP/50006/2020 DOI 10.54499/UIDP/50006/2020 and UIDB/50006/2020 DOI 10.54499/UIDB/50006/2020), through national funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CaCl2 | Calcium Chloride |

| CDW | Cold Distilled Water |

| ECP | Ether Clarification Procedure |

| FACS | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting |

| HBSS | Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution |

| HCl | Hydrogen Chloride |

| IMS | Immunomagnetic Separation |

| KCl | Potassium Chloride |

| MSS | Magnetic Separation System |

| NaCl | Sodium Chloride |

| NaHCO3 | Sodium Bicarbonate |

| NaOH | Sodium Hydroxide |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PBST | Phosphate-Buffered Saline with 0.01% Tween 20 |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SFM | Sucrose Flotation Method |

| SPIDER | Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type |

| STP | Swiss Tropic Institute |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Ahmed, M. Intestinal Parasitic Infections in 2023. Gastroenterol. Res. 2023, 16, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savioli, L.; Smith, H.; Thompson, A. Giardia and Cryptosporidium join the ‘Neglected Diseases Initiative’. Trends Parasitol. 2006, 22, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, R.D. Giardia duodenalis: Biology and Pathogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, e00024-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.K.C.; Leung, A.A.M.; Wong, A.H.C.; Sergi, C.M.; Kam, J.K.M. Giardiasis: An Overview. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2019, 13, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, E.W.; Schaefer, F.W. Improved In Vitro Excystation Procedure for Giardia lamblia Cysts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1981, 14, 709–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, S.E.; Gillin, F.D. Excystation of in vitro-derived Giardia lamblia cysts. Infect. Immun. 1990, 58, 3516–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, M.Y.; Shapiro, D.; Singer, S.M. Giardia lamblia: Laboratory Maintenance, Lifecycle Induction, and Infection of Murine Models. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2020, 57, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keserue, H.A.; Füchslin, H.P.; Egli, T. Rapid detection and enumeration of Giardia lamblia cysts in water samples by immunomagnetic separation and flow cytometric analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 5420–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Teztzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConn, B.R.; Kraft, A.L.; Durso, L.M.; Ibekwe, A.M.; Frye, J.G.; Wells, J.E.; Tobey, E.M.; Ritchie, S.; Williams, C.F.; Cook, K.L.; et al. An analysis of culture-based methods used for the detection and isolation of Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus spp. from surface water: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Adaway, A.I.; Elmallawnay, M.A.; Nahnoush, R.K.M.; Hassanin, O.M. Sucrose Density-Gradient Isolation Method Intended For Improvement Of Sample Purity Prior To Amplification Of Giardia Β-Giardin Gene. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2017, 47, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.A.; Lee, E.; Tan, I.T.L.; Mohamad-Kamel, A.G. Occurrence of Giardia cysts and Cryptosporidium oocysts in raw and treated water from two water treatment plants in Selangor, Malaysia. Water Res. 1997, 31, 3132–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tukhi, M.H.; Al-Ahdal, M.N.; Peters, W. A simple method for excystation of Giardia lamblia cysts. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1991, 85, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, M.E.; Wasserman, M. Quick and efficient purification of Giardia intestinalis cysts from fecal samples. Parasitol. Res. 2006, 99, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barash, N.R.; Nosala, C.; Pham, J.K.; McInally, S.G.; Gourguechon, S.; McCarthy-Sinclair, B.; Dawson, E.C. Giardia Colonizes and Encysts in High-Density Foci in the Murine Small Intestine. mSphere 2017, 2, e00343-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barazesh, A.; Majidi, J.; Fallah, E.; Gholikhani, R. Introducing a simple and economical method to purify Giardia lamblia cysts. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 8498–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénéré, E.; Da Luz, R.A.I.; Vermeersch, M.; Cos, P.; Maes, L. A new quantitative in vitro microculture method for Giardia duodenalis trophozoites. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 71, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, I.; Gantzer, C.; Chesnot, T.; Schwartzbrod, J. Improved specificity for Giardia lamblia cyst quantification in wastewater by development of a real-time PCR method. J. Microbiol. Methods 2004, 57, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, I.; Maux, M.; Helmi, K.; Hoffmann, L.; Schwartzbrod, J.; Cauchie, H.M. Quantification of Giardia transcripts during in vitro excystation: Interest for the estimation of cyst viability. Water Res. 2009, 43, 2728–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezagio, R.C.; Colli, C.M.; Romera, L.I.L.; de Almeida, C.R.; Ferreira, C.; Mattia, S.; Gomes, M.L. Improvement in cyst recovery and molecular detection of Giardia duodenalis from stool samples. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielec, L.; Boisvert, T.C.; Jackson, S.G. Modified procedure for recovery of Giardia cysts from diverse water sources. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 22, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breternitz, B.S.; Dropa, M.; Martone-Rocha, S.; Ferraro, P.S.P.; Peternella, F.A.S.; Silva, M.L.; Razzolini, M.T.P. Safe drinking water: To what extent are shallow wells reliable? J Water Health 2024, 22, 2184–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Hermida, J.A.; García-Presedo, I.; Almeida, A.; González-Warleta, M.; Costa, J.M.C.D.; Mezo, M. Presence of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis through drinking water. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 405, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, A.; Sousa, M.I.; Azeredo, Z.; Leite, E.; de Sousa, J.C.F.; Cabral, M. Isolation, excystation and axenization of Giardia lamblia isolates: In vitro susceptibility to metronidazole and albendazole. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 1017–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araújo, R.S.; Aguiar, B.; Dropa, M.; Razollini, M.T.P.; Sato, M.I.Z.; Lauretto, M.S.; Galvani, A.T.; Padula, J.A.; Matté, G.R.; Matté, M.H. Detection and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium species and Giardia assemblages in two watersheds in the metropolitan region of São Paulo, Brazil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 15191–15203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghani-Samani, A.; Madreseh-Ghahfarokhi, S.; Dehghani-Samani, A.; Pirali, Y. In-vitro antigiardial activity and GC-MS analysis of Eucalyptus globulus and Zingiber officinalis essential oils against Giardia lamblia cysts in simulated condition to human’s body. Ann. Parasitol. 2019, 65, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Douglas, H.; Reiner, D.S.; Gillin, F.D. A new method for purification of Giardia lamblia cysts. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1987, 81, 315–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feely, D.E.; Erlandsen, S.L. Isolation and Purification of Giardia Trophozoites from Rat Intestine. J. Parasitol. 1981, 67, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, B.C.; Stoner, K.; Bergquist, P.L. Applying fluorescence based technology to the recovery and isolation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from industrial wastewater streams. Water Res. 2006, 40, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, B.C.; Veal, D. Analysis-only detection of Giardia by combining immunomagnetic separation and two-color flow cytometry. Cytom. A 2003, 51, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fradette, M.-S.; Culley, A.I.; Charette, S.J. Detection of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. in Environmental Water Samples: A Journey into the Past and New Perspectives. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmour, R.A.; Smith, H.V.; Smith, P.G.; Morris, G.P.; Girdwood, R.W.A. The Occurence and Viability of Giardia spp. Cysts in UK Waters. Water Sci. Technol. 1991, 24, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordts, B.; Hemelhof, W.; Tilborgh, K.V.V.; Retoré, P.; Cadranel, S.; Butzler, J.P. Evaluation of a new method for routine in vitro cultivation of Giardia lamblia from human duodenal fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1985, 22, 702–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, B.M.; Huang, C. Recovery of Giardia and Cryptosporidium from water by various concentration, elution, and purification techniques. J. Environ. Qual. 2000, 29, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac-Renton, J.L.; Shahriari, H.; Bowie, W.R. Comparison of an in vitro method and an in vivo method of Giardia excystation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 1530–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massanet-Nicolau, J. New method using sedimentation and immunomagnetic separation for isolation and enumeration of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts and Giardia lamblia cysts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6758–6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, A.V.; Ward, H.D.; Keusch, G.T.; Pereira, M.E.A. In vitro Encystation of Giardia lamblia: Large-Scale Production of In vitro Cysts and Strain and Clone Differences in Encystation Efficiency. J. Parasitol. 1991, 77, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanis, P.; Sotiriadou, I.; Kartashev, V.; Kourenti, C.; Tsvetkova, N.; Stojanova, K. Occurrence of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in water supplies of Russia and Bulgaria. Environ. Res. 2006, 102, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Z.; Wen, J. A rapid and inexpensive method for the isolation and identification of Giardia. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, H.A.; Boparai, R.S.; Warner, J.J.; Mowery, S.F.; Smith, A.C.; Cummins, A.P.; Wittmann, J.L.; Fiore, D.C. Survey of Pathologic Microorganisms in the Streams Along the Tahoe Rim Trail. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2025, 36, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, R.C.; dos Santos, L.U.; Sato, M.I.Z.; Franco, R.M.B. Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. in surface water supply of Campinas, Southeast Brazil. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 62, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.O.; Urbano, L.; Neto, R.C. Immunomagnetic separation study applied to detection of Giardia spp. cysts and Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts in water samples. Water Supply 2016, 16, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polverino, D.; Molina, N.B.; Minvielle, M.C.; Lozano, M.E.; Basualdo, J.Á. Técnicas de purificación y ruptura de quistes de Giardia spp. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2004, 36, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan, Q.; Christophe, L.; Teo, W.; ShuJun, L.; Hua, F.H. Flow-through immunomagnetic separation system for waterborne pathogen isolation and detection: Application to Giardia and Cryptosporidium cell isolation. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 673, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Roubin, M.R.; Pharamond, J.S.; Zanelli, F.; Poty, F.; Houdart, S.; Laurent, F.; Drocourt, J.L.; Poucke, S.V. Application of laser scanning cytometry followed by epifluorescent and differential interference contrast microscopy for the detection and enumeration of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in raw and potable waters. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 93, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.U.; Bonatti, T.R.; Neto, R.C.; Franco, R.M.B. Occurrence of Giardia cysts and Cryptosporidium oocysts in activated sludge samples in Campinas, SP, Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2004, 46, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauch, J.F.; Flanigan, D.; Galvin, M.L.; Berman, D.; Jakubowski, W. Propidium iodide as an indicator of Giardia cyst viability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 3243–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirlpanth, C.; Chlntana, T.; Tharaphan, Y.; Lekkra, A. Cloning of Thai Strain Giardia intestinalis. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 1995, 13, 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sroka, J.; Stojecki, K.; Zdybel, J.; Karamon, J.; Cencek, T.; Dutkiewicz, J. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts in effluent from sewage treatment plant from eastern Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2013, 13, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Terrones, K.T.; Carranza, G.R.; Fabián, M.B. Evaluation of methods of concentration and purification of Giardia spp. from coprological samples. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2019, 36, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uda-Shimoda, C.F.; Colli, C.M.; Pavanelli, M.F.; Falavigna-Guilherme, A.L.; Gomes, M.L. Simplified protocol for DNA extraction and amplification of 2 molecular markers to detect and type Giardia duodenalis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 78, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wei, B.; Jiang, Q.; Yu, X. Detecting Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia by coagulation concentration and real-time PCR quantification. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2013, 7, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanevik, K.; Bakken, R.; Brattbakk, H.R.; Saghaug, C.S.; Langeland, N. Whole genome sequencing of clinical isolates of Giardia lamblia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 192.e1–192.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keister, D.B. Axenic culture of Giardia lamblia in TYI-S-33 medium supplemented with bile. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1983, 77, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballweber, L.R.; Beugnet, F.; Marchiondo, A.A.; Payne, P.A. American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists’ review of veterinary fecal flotation methods and factors influencing their accuracy and use—Is there really one best technique? Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 204, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandamme, T.F.; Lenourry, A.; Charrueau, C.; Chaumeil, J.C. The use of polysaccharides to target drugs to the colon. Carbohydr. Polym. 2002, 48, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, F.W.; Rice, E.W.; Hoff, J.C. Factors promoting in vitro excystation of Giardia muris cysts. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1984, 78, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillin, F.D.; Boucher, S.E.; Rossi, S.S.; Reiner, D.S. Giardia lamblia: The roles of bile, lactic acid, and pH in the completion of the life cycle in vitro. Exp. Parasitol. 1989, 69, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).