Saccharomyces cerevisiae TAD1 Mutant Strain As Potential New Antimicrobial Agent: Studies on Its Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Preparation of CFS from S. cerevisiae

2.3. Establishing Yeast Growth Curves

2.4. Growth Curve

2.5. Inhibitory Activity of S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Against Different Bacteria

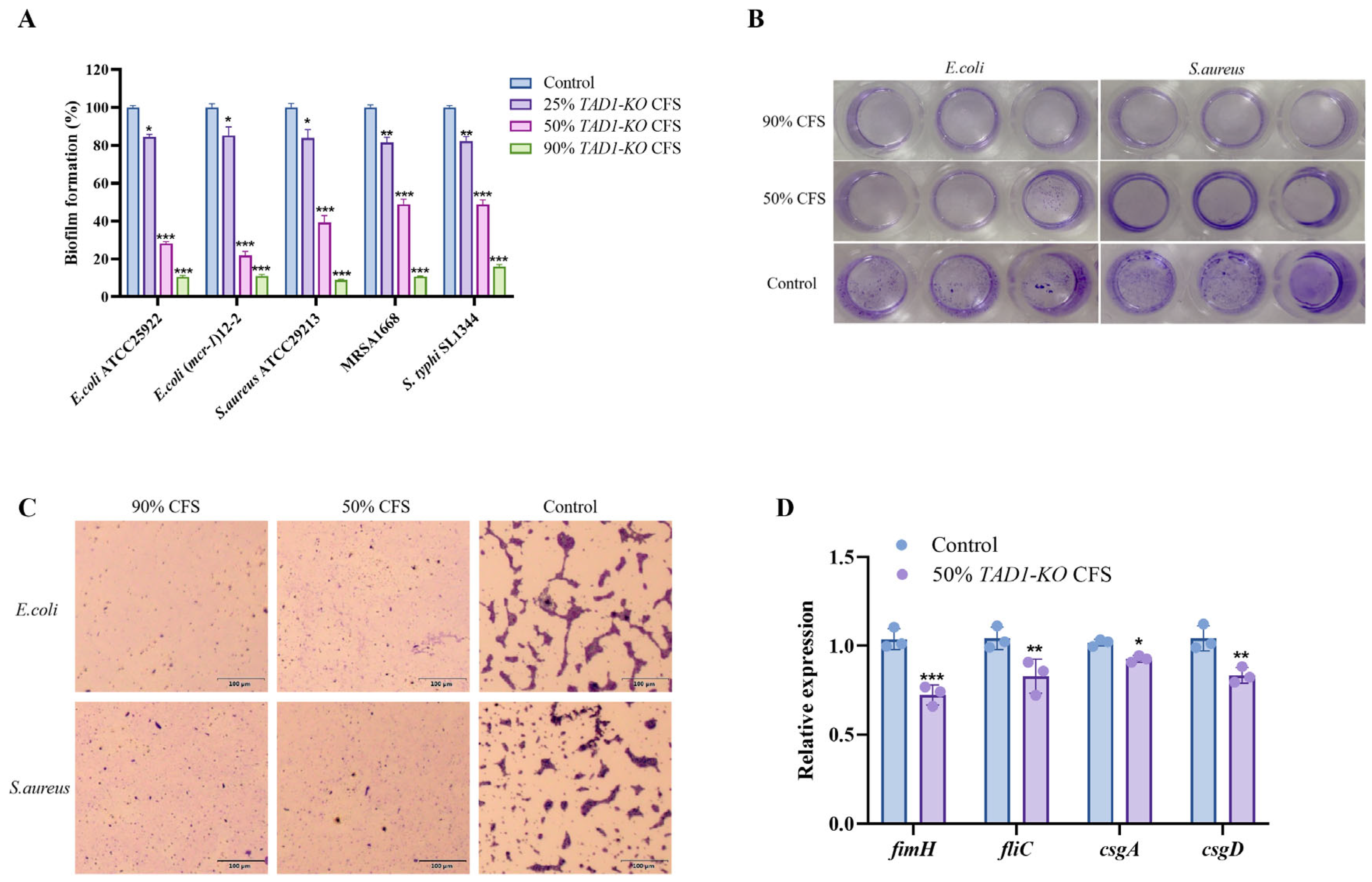

2.6. Biofilm Inhibition Assay

2.7. Expression of E. coli Biofilm-Related Genes

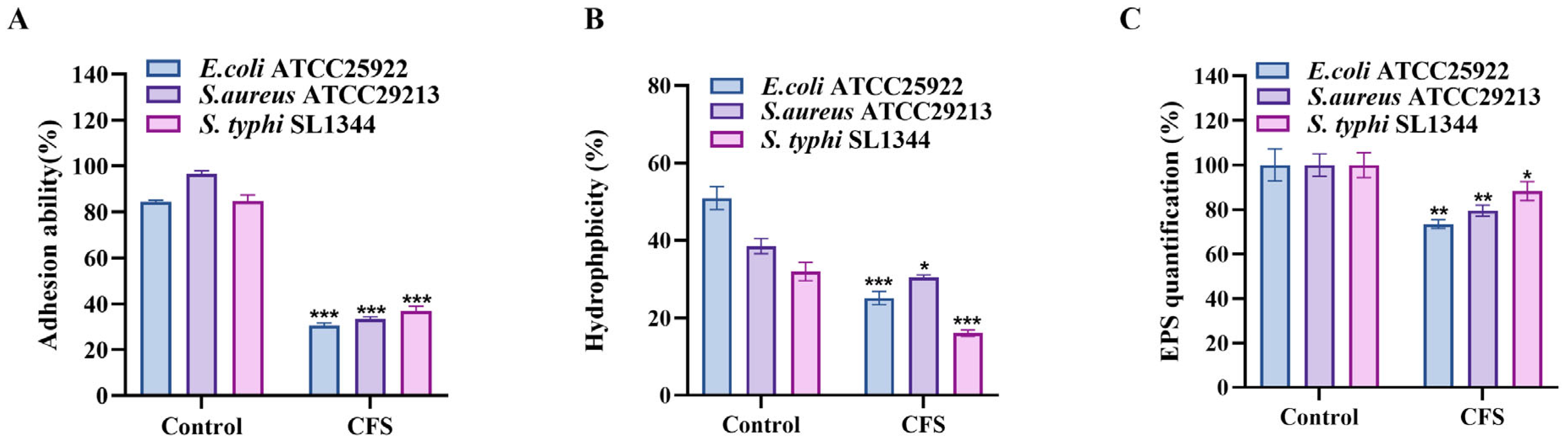

2.8. Adhesion Ability to the Glass Surface

2.9. Hydrophobicity Assay

2.10. Exopolysaccharides (EPS) Production

2.11. Kinetics of E. coli Killing by CFS

2.12. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

2.13. Effect of S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS on Cell Wall Integrity of E. coli

2.14. Determination of Extracellular Membrane Permeability

2.15. Determination of Intracellular Membrane Permeability

2.16. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Relative Fluorescence Intensity Determination

2.17. Bacterial Intracellular ROS Inhibition Assay

2.18. Probiotic Potential of S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO

- (1)

- Tolerance of S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO to artificially simulated gastroenteric fluid:

- (2)

- Auto-aggregation Ability Assay: Auto-aggregation of S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO and its co-aggregation with E. coli, S. aureus, and S. typhi were assessed in parallel, with BY4743 and S. boulardii serving as the reference and positive control, respectively. Yeast strains grown overnight were harvested, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in the same buffer to an OD600 of ≈0.5 (A0). Suspensions were left undisturbed at room temperature; after 5 h; the OD600 of the upper phase was recorded (Aₜ). Auto-aggregation (%) was calculated using the following equation:

- (3)

- Co-aggregation Ability Assay: Overnight cultures of E. coli, S. aureus, and S. typhi were harvested (8000× g, 4 °C, 10 min), washed twice, and resuspended in PBS to an OD600 ≈ of 0.5 (A1). Yeast suspensions (S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO, BY4743, or S. boulardii) were prepared identically (A2). Subsequently, 2 mL of each yeast suspension was mixed with 2 mL of the corresponding bacterial suspension, incubated statically at 37 °C for 5 h, and the OD600 of the upper phase was recorded (A3). Co-aggregation (%) was calculated using the following equation:

2.19. Killing Model of the Moth Galleria mellonella

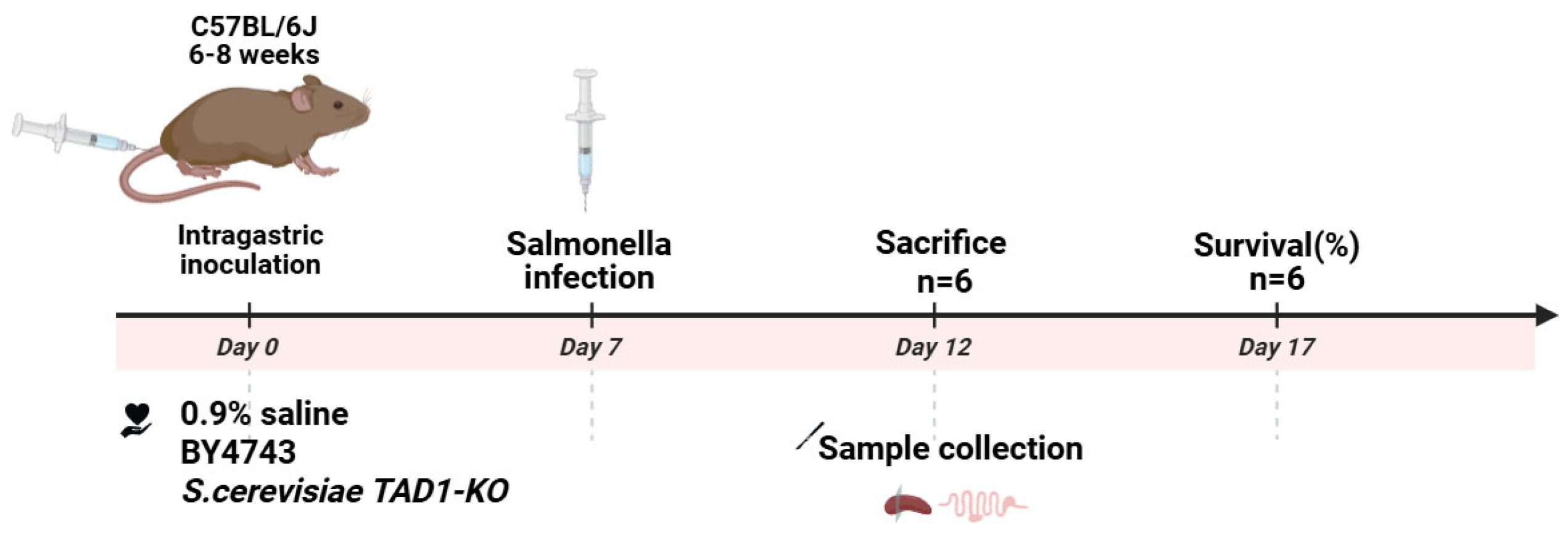

2.20. Mouse Model of Enteritis

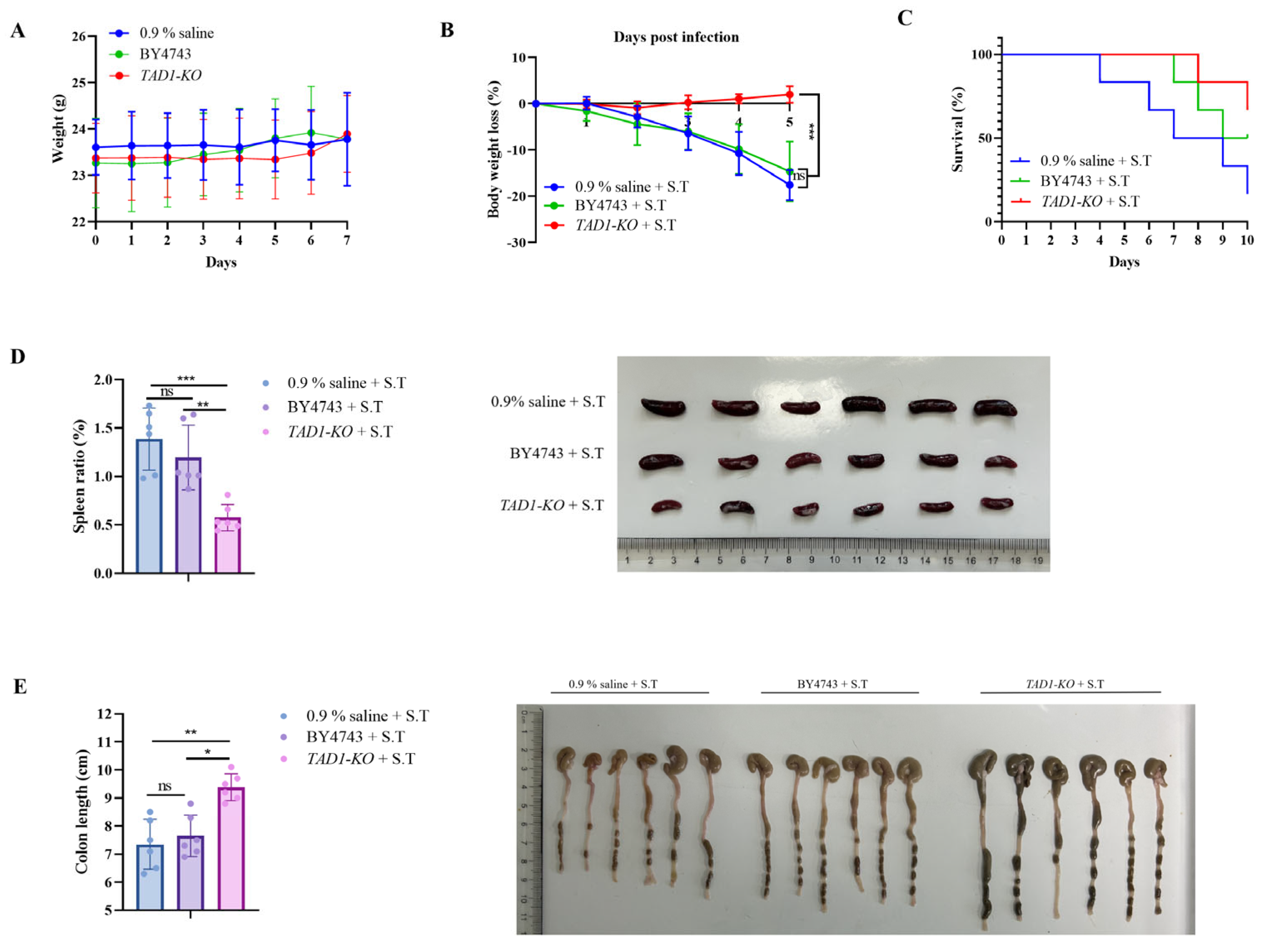

- (1)

- The enteritis model of mice infected by S. typhi SL1344 was established. Specific-pathogen-free grade male C57BL/6J mice, each at 6–8 weeks of age, weighing 16–20 g, were purchased from Jiangsu Jicui Pharmachem Biotechnology Co. (Nanjing, China), Laboratory Animal Production License No. SCXK (Su) 2018-0008; Laboratory Animal Use License No. SYXK (Su) 2020-0048 (barrier environment). All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Medical University.

- (2)

- SPF male C57BL/6J mice were acclimated for one week prior to experimentation. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO and BY4743 were harvested, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended at 5.0 × 108 CFU mL−1. Thirty-six mice were randomly allocated into three groups (n = 12 each) and gavaged once daily for 7 days with 0.1 mL of: S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO suspension, BY4743 suspension, 0.9% saline (control). Animals were identified by tail markings; their general appearance and body weight were recorded daily. Safety endpoints were evaluated by comparing the two yeast groups with the saline control. The specific procedure showed in Figure 1.

- (3)

- Each of the three treatment groups was split into two sub-cohorts (n = 6). Sub-cohort 1 (5-day infection study): Mice were challenged orally with 1 × 107 CFU mL−1 of S. typhi and weighed daily. On day 5, the animals were euthanised; the ileum, colon, and caecum were aseptically removed. Intestinal tissue segments were weighed and homogenized in 1 mL of 0.1% Triton X-100. Serial dilutions were plated on an LB plate supplemented with 200 µg mL−1 of streptomycin to enumerate S. typhi, and on YPD plates supplemented with 200 µg mL−1 of chloramphenicol to quantify S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO colonization. Sub-cohort 2 (survival study): After an identical challenge, mice were monitored for 10 days, and survival was recorded.

- (4)

- The spleens of the three groups of mice were weighed and photographed, and the spleen index was calculated. We used the following equation to calculate the spleen index (%): spleen index (%) = (spleen weight/body weight) × 100.

- (5)

- Three groups of mouse colon tissues were taken to measure the length and were photographed.

- (6)

- Histomorphometry: The terminal 2 cm of ileum was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 µm. Hematoxylin–eosin-stained (H&E) slides were examined under light-microscopy; images were captured for assessment of villus architecture, inflammatory infiltration, and epithelial integrity.

- (7)

- Quantitative Real-Time PCR: Total RNA was extracted from the ileal segments with TRIzol (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) and quantified on a NanoDrop-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, US); only samples with A260/A280 ≥ 1.9 were processed. cDNA was synthesized using a reverse-transcription kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). Quantitative PCR was performed in a Light Cycler 480 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Biosharp, Hefei, China) and gene-specific primers (Sangon Biotech; Supplementary Material Table S2). Transcript levels of IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, Occludin, Claudin-1, and ZO-1 were normalized to β-actin and expressed as 2(−ΔΔCt).

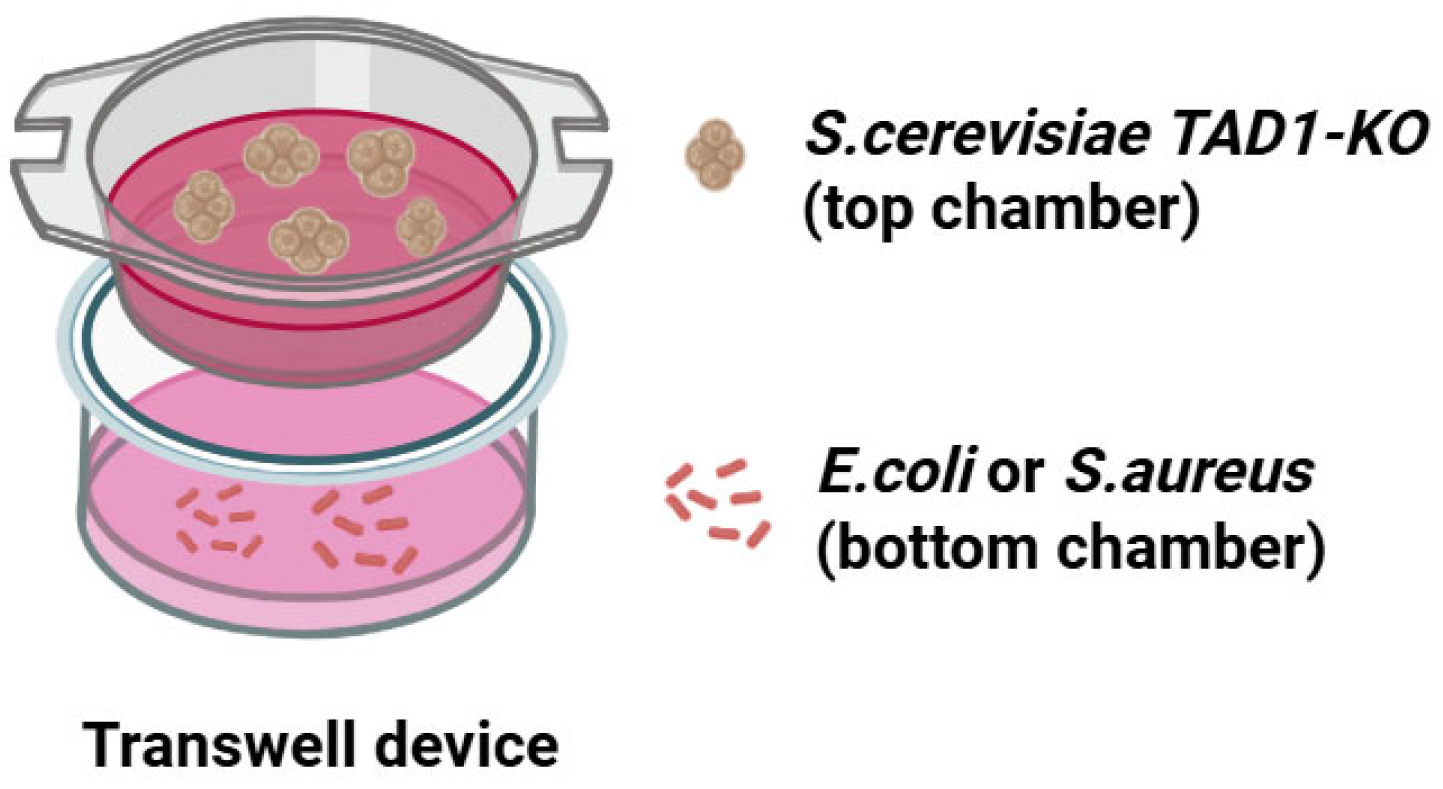

2.21. Cell–Cell Culture Model

2.22. Transwell Experiment

2.23. Mebabolomic Analysis

2.24. pH Neutralization Experiment

2.25. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Knockout of the TAD1 Gene in S. cerevisiae Basically Does Not Result in a Drastic Change in Proliferation Rate

3.2. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Inhibits Proliferation of E. coli, S. aureus, and S. typhi

3.3. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Can Also Inhibit the Proliferation of Many Pathogenic Bacteria

3.4. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Inhibits Biofilm Formation of Pathogenic Bacteria

3.5. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Could Reduce Adhesion, Surface Hydrophobicity, and EPS Production of E. coli, S. aureus, and S. typhi

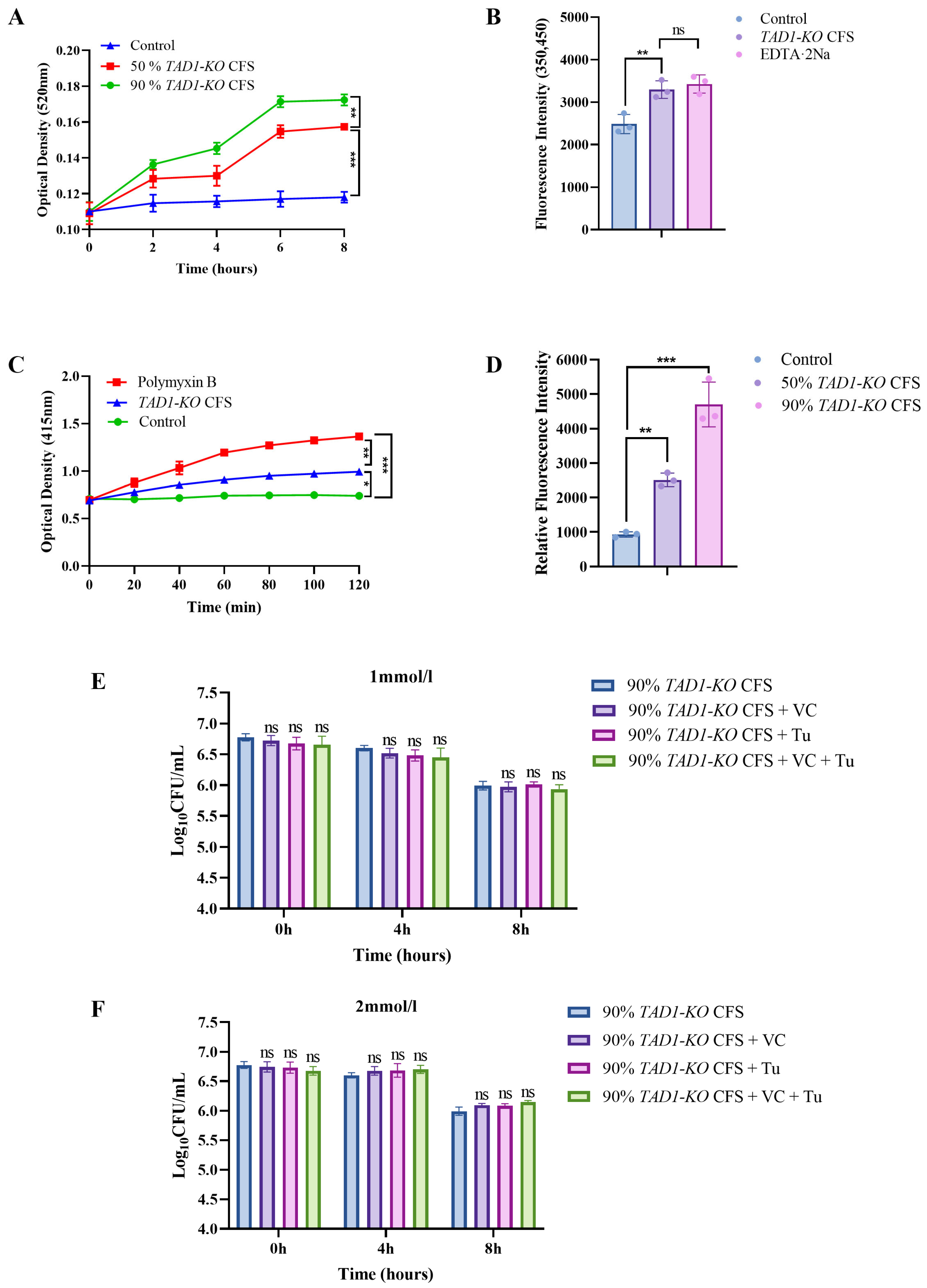

3.6. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Has a Certain Bactericidal Effect on E. coli

3.7. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Can Damage the Integrity of E. coli’s Cell Wall and Affect the Permeability of the Cell Membrane

3.8. ROS As a Byproduct: S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Kills Bacteria via Direct Cell Structure Damage

3.9. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO Has Good Probiotic Properties

3.9.1. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO Had Good Tolerance to Artificial Gastric and Intestinal Fluids

3.9.2. Auto-Aggregation and Co-Aggregation

3.10. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO Has Antibacterial Therapeutic Effect In Vivo

3.10.1. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO Could Prolong the Survival Time of G. mellonella

3.10.2. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO Has Therapeutic and Protective Effects on Enteritis in Mice Caused by S. typhi

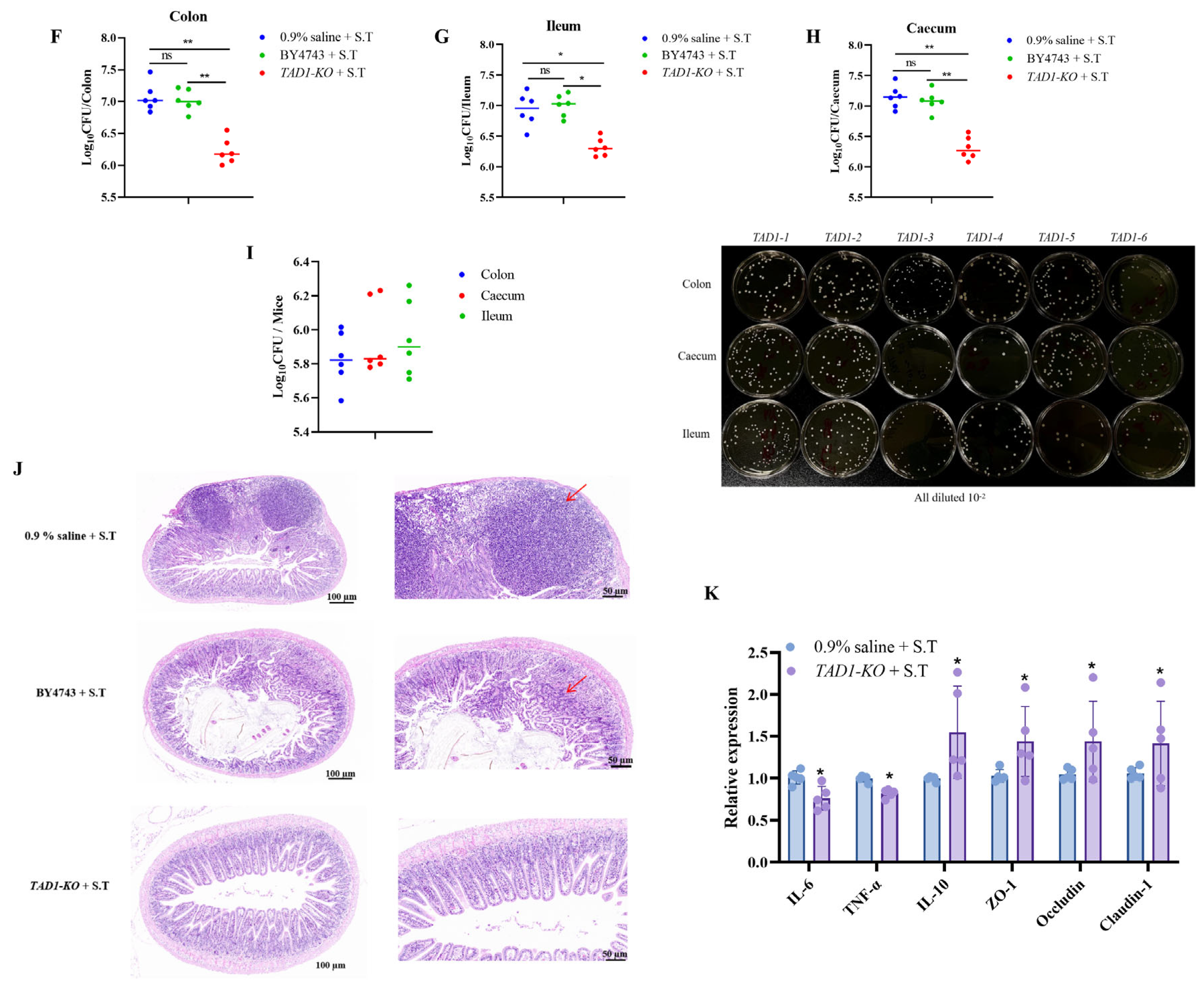

3.11. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO Inhibits the Proliferation of E. coli, S. aureus, and S. typhi

3.12. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO Produces Antimicrobial Effects by Secreting Active Metabolites

3.13. Metabolomics Analyses Suggested That the Metabolites Exerting Antimicrobial Effects in S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS Were Mainly Organic Acids

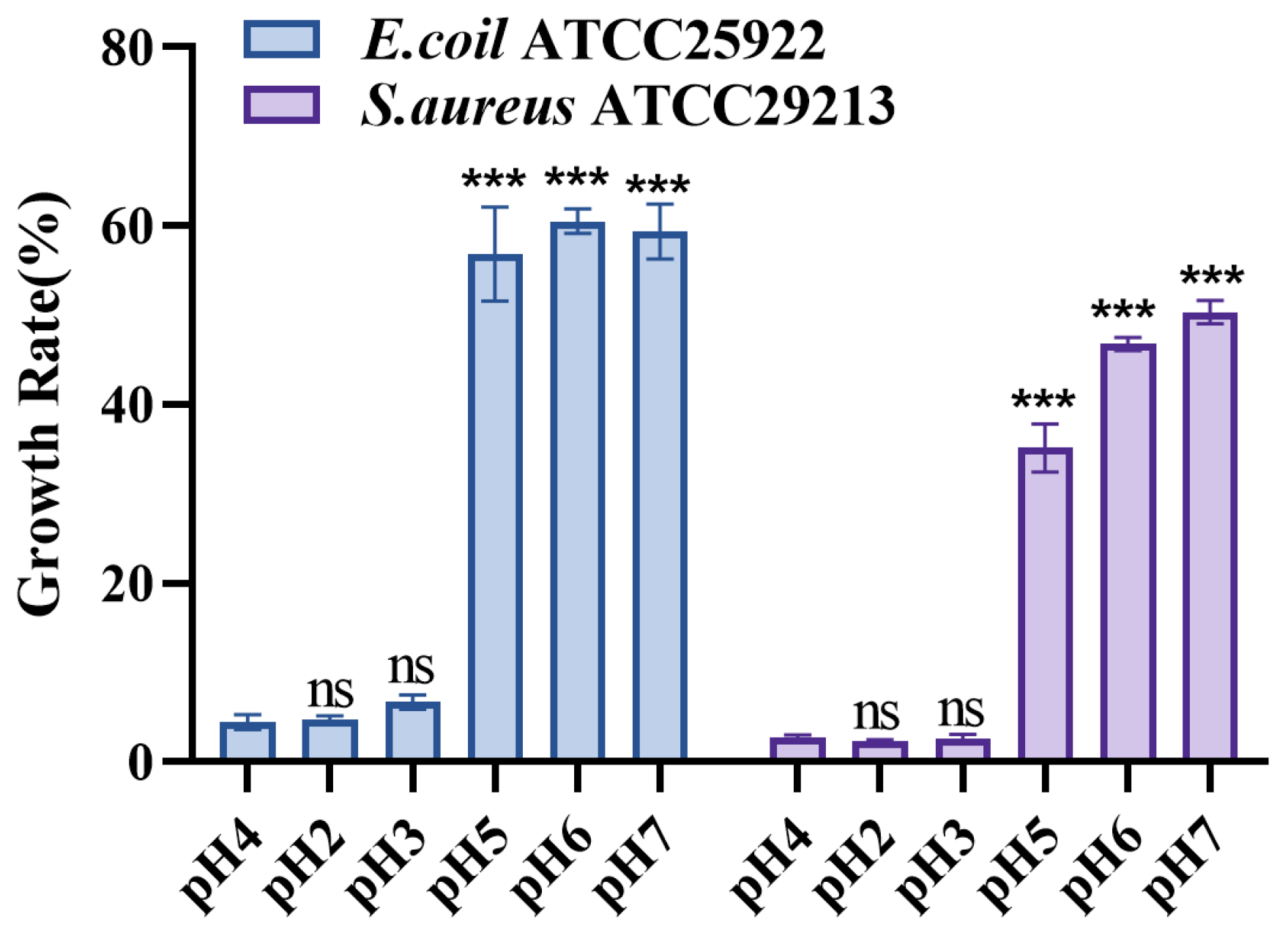

3.14. S. cerevisiae TAD1-KO CFS pH Neutralization Attenuates the Inhibitory Effect on E. coli and S. aureus

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Qi, H.; Qiao, F.; Yao, H. Isolation and evaluation of Pediococcus acidilactici YH-15 from cat milk: Potential probiotic effects and antimicrobial properties. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Yu, H.H.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, N.K.; Paik, H.D. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Cell-Free Supernatant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae against Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Ruszkowski, J.; Fic, M.; Folwarski, M.; Makarewicz, W. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745: A Non-bacterial Microorganism Used as Probiotic Agent in Supporting Treatment of Selected Diseases. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, H.; Bischoff, S.C. Influence of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 on the gut-associated immune system. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2016, 9, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, S.; Chen, C.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Y. BTS1-knockout Saccharomyces cerevisiae with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity through lactic acid accumulation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1494149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.Y.; Liu, S.; Patel, M.H.; Glenzinski, K.M.; Skory, C.D. Saccharomyces cerevisiae surface display of endolysin LysKB317 for control of bacterial contamination in corn ethanol fermentations. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1162720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, L.; Hensel, A. β-Glucans from Saccharomyces cerevisiae as antiadhesive and immunomodulating polysaccharides against Campylobacterjejuni. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 206, 107847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Bai, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Meng, R.; Guo, N. Inhibitory Effect of Non-Saccharomyces Starmerella bacillaris CC-PT4 Isolated from Grape on MRSA Growth and Biofilm. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, R.; Shah, N.P. Immune system stimulation by probiotic microorganisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, S.; Ganapathy, S.; Mitra, M.; Neha; Kumar Joshi, D.; Veligandla, K.C.; Rathod, R.; Kotak, B.P. Unique Properties of Yeast Probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e46314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Gao, X.; Yuan, R. Production of bioethanol by Normal, Atmospheric Temperature and Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Mutaengensis Combined with Hydrolysate of Corn Straw. Food Ferment. Ind. 2020, 46, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Yu, W.; Lyu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Chen, J.; Liu, L. Metabolic engineering modification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for efficient Synthesis of β-glucan. J. Food Ferment. Ind. 2022, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qin, J.; Huang, Y.; Tang, B.; Wang, H. Functional Characteristics of the transitional State Regulator AbrB of Bacillus microspore. J. Southwest Agric. Sci. 2023, 36, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zou, Y.; Dai, H.; Li, S.; Cai, Y. Rapid knockout of Escherichia coli ptsHIcrr operon and determination of knockout bacteria growth performance. Bull. Microbiol. 2010, 37, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, D.B. Emerging Infectious Diseases. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2019, 54, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.J.; Yu, H.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, N.K.; Paik, H.D. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Grapefruit Seed Extract against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Bai, F.; Sun, M.; Lu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Du, H. Research on Bread Lactobacillus ZHG 2–1 as a Novel Group Synchronization Inhibitor to Reduce Biofilm Formation and Toxin Function of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference of the Chinese Institute of Food Science and Technology and the 10th US-China Food Industry High-level Forum: 2019, Wuhan, China, 13–14 November 2019; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, S.; Sharma, P.; Kalia, N.; Singh, J.; Kaur, S. Anti-biofilm Properties of the Fecal Probiotic Lactobacilli Against Vibrio spp. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, S.; Pradhan, B.; Roychowdhury, A. Complete genome sequence, metabolic profiling and functional studies reveal Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS-ARS2 is a promising biofilm-forming probiotic with significant antioxidant, antibacterial, and antibiofilm potential. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1535388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schembri, M.A.; Pallesen, L.; Connell, H.; Hasty, D.L.; Klemm, P. Linker insertion analysis of the FimH adhesin of type 1 fimbriae in an Escherichia coli fimH-null background. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1996, 137, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, X.; Pei, S.; Zhao, M.; Li, Y. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of Five flagellin fliC genes of Cronobact. J. Jiangsu Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 33, 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Peng, H.; Li, S.; Xie, X.; Shi, Q. Molecular Function of csgA, Amyloid protein-coding gene of Citrobacter Wegengenii. Ind. Microbiol. 2021, 51, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.; Cimdins, A.; Beske, T.; Römling, U. Detailed analysis of c-di-GMP mediated regulation of csgD expression in Salmonella typhimurium. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X. Response Mechanism of Cryostress of Staphylococcus aureus and Inhibitory Effect of Chickpein A on Its Film. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Jilin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Naito, Y.; Tohda, H.; Okuda, K.; Takazoe, I. Adherence and hydrophobicity of invasive and noninvasive strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 1993, 8, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luan, Z.; Fan, Z.; Wu, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, T.; Wang, H. Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, and Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides Obtained from Fresh Sarcotesta of Ginkgo biloba: Bioactive Polysaccharide that Can Be Exploited as a Novel Biocontrol Agent. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 5518403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrino, B.; Schillaci, D.; Carnevale, I.; Giovannetti, E.; Diana, P.; Cirrincione, G.; Cascioferro, S. Synthetic small molecules as anti-biofilm agents in the struggle against antibiotic resistance. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 161, 154–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Yao, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, H.; Xu, C.; Yin, H. Research on the Killing Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticles against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. J Acta Sci. Sci. Anal. 2011, 27, 799–801. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. Protective Effect of Sodium Humate on Intestinal Injury Caused by Escherichia coli and Prevention and Control of Diarrhea in Calves. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Sun, Y.; Pan, D.; Cao, J.; Zeng, X.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X. The Inhibition Mechanism of Main Components of Rosemary on Salmonella. J. Chin. J. Food Sci. 2019, 19, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L.; Wenling, Q.; Mauro, P.; Stefano, B. Antibacterial Agents Targeting the Bacterial Cell Wall. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 2902–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efenberger-Szmechtyk, M.; Nowak, A.; Czyżowska, A.; Śniadowska, M.; Otlewska, A.; Żyżelewicz, D. Antibacterial mechanisms of Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.), Chaenomeles superba Lindl. and Cornus mas L. leaf extracts. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.R.; Sugimoto, Y.; Aoki, T. Ovotransferrin antimicrobial peptide (OTAP-92) kills bacteria through a membrane damage mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1523, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, S.; Cirillo, P.; Paglia, A.; Sasso, L.; Di Palma, V.; Chiariello, M. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease: Does the actual knowledge justify a clinical approach? Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2010, 8, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.J.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Z.W.; Liu, C.X.; Cai, C.X.; Li, J.; Yu, X.Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Wang, N. Kill Two Birds with One Stone: Dual-Metal MOF-Nanozyme-Decorated Hydrogels with ROS-Scavenging, Oxygen-Generating, and Antibacterial Abilities for Accelerating Infected Diabetic Wound Healing. Small 2024, 20, e2403679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. 5-Lipoxygenase Mediates Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage Caused by Benzo(a)pyrene in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Master’s Thesis, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lohith, K.; Anu-Appaiah, K.A. Antagonistic effect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae KTP and Issatchenkia occidentalis ApC on hyphal development and adhesion of Candida albicans. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Malakar, P.K.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y. The Fate of Bacteria in Human Digestive Fluids: A New Perspective Into the Pathogenesis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Yu, H.H.; Song, Y.J.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, N.-K.; Paik, H.-D. Anti-biofilm effect of the cell-free supernatant of probiotic Saccharomyces cerevisiae against Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Control 2021, 121, 107667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Pereira, G.V.; de Oliveira Coelho, B.; Magalhães Júnior, A.I.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. How to select a probiotic? A review and update of methods and criteria. Biotechnol Adv. 2018, 36, 2060–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, R.; Haba, A.; Wang, X.; Parida, A. Research Status of Galleria mellonella Medical Fungal Infection Model. J. Mycol. 2019, 38, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, I.; Verdial, C.; Tavares, L.; Oliveira, M. The Virtuous Galleria mellonella Model for Scientific Experimentation. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.J.; Loh, J.M.; Proft, T. Galleria mellonella infection models for the study of bacterial diseases and for antimicrobial drug testing. Virulence 2016, 7, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Li, M.; Xu, D.; Gao, R. Establishment and Phenotypic Analysis of Intestinal Model of Salmonella Typhimurium Infection in C57BL/6 Mice. J. Chin. J. Comp. Med. 2017, 27, 33–36+45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, K.; Deng, S.; Liu, Y. Sodium Humate-Derived Gut Microbiota Ameliorates Intestinal Dysfunction Induced by Salmonella Typhimurium in Mice. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0534822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; He, Y.; Liu, K.; Deng, S.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y. Sodium Humate Alleviates Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-Induced Intestinal Dysfunction via Alteration of Intestinal Microbiota and Metabolites in Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 809086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Ding, C.; Chi, C.; Liu, S.; Gao, Z.; Sun, W.; Zhao, H.; Song, S. Lactobacillus crispatus 7–4 Mitigates Salmonella typhimurium-Induced Enteritis via the γ-Glutamylcysteine-Mediated Nrf2 Pathway. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 17, 3378–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunyeit, L.; Kurrey, N.K.; Anu-Appaiah, K.A.; Rao, R.P. Probiotic Yeasts Inhibit Virulence of Non-albicans Candida Species. mBio 2019, 10, e02307–e02319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, T.Y.; Liu, G.; Ye, Y.; Soteyome, T.; Seneviratne, G.; Xiao, G.; Xu, Z.; Kjellerup, B.V. Microbial Interaction between Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Transcriptome Level Mechanism of Cell-Cell Antagonism. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0143322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunyeit, L.; Kurrey, N.K.; Anu-Appaiah, K.A.; Rao, R.P. Secondary Metabolites from Food-Derived Yeasts Inhibit Virulence of Candida albicans. mBio 2021, 12, e0189121, Erratum in mBio 2021, 12, e0282821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kuo, S.; Shu, M.; Yu, J.; Huang, S.; Dai, A.; Two, A.; Gallo, R.L.; Huang, C.M. Staphylococcus epidermidis in the human skin microbiome mediates fermentation to inhibit the growth of Propionibacterium acnes: Implications of probiotics in acne vulgaris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieuleveux, V.; Guéguen, M. Antimicrobial effects of D-3-phenyllactic acid on Listeria monocytogenes in TSB-YE medium, milk, and cheese. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 1281–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pazo, N.; Vázquez-Araújo, L.; Pérez-Rodríguez, N.; Cortés-Diéguez, S.; Domínguez, J.M. Cell-free supernatants obtained from fermentation of cheese whey hydrolyzates and phenylpyruvic acid by Lactobacillus plantarum as a source of antimicrobial compounds, bacteriocins, and natural aromas. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 171, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, J. d-Amino Acids and Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Guevarra, R.B.; Kim, Y.T.; Kwon, J.; Kim, H.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, H.B.; Lee, J.H. Role of Probiotics in Human Gut Microbiome-Associated Diseases. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, S.; Deans, A.; Padua-Zamora, A.; Gregorio, G.V.; Li, C.; Dans, L.F.; Allen, S.J. Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 12, Cd003048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Şanlier, N.; Gökcen, B.B.; Sezgin, A.C. Health benefits of fermented foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambrani, R.; Abdolalizadeh, J.; Kohan, L.; Jafari, B. Recent advances in the application of probiotic yeasts, particularly Saccharomyces, as an adjuvant therapy in the management of cancer with focus on colorectal cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Brunser, O.; Szajewska, H. Saccharomyces boulardii in childhood. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2009, 168, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berni Canani, R.; Cucchiara, S.; Cuomo, R.; Pace, F.; Papale, F. Saccharomyces boulardii: A summary of the evidence for gastroenterology clinical practice in adults and children. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 15, 809–822. [Google Scholar]

- Saidi, N.; Owlia, P.; Marashi, S.M.A.; Saderi, H. Inhibitory effect of probiotic yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae on biofilm formation and expression of α-hemolysin and enterotoxin A genes of Staphylococcus aureus. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2019, 11, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennequin, C.; Thierry, A.; Richard, G.F.; Lecointre, G.; Nguyen, H.V.; Gaillardin, C.; Dujon, B. Microsatellite typing as a new tool for identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Patel, N.G.; Levy, M.A.; Storeygard, A.; Balk, D.; Gittleman, J.L.; Daszak, P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008, 451, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Jin, X.; Hong, S.H. Probiotic Escherichia coli inhibits biofilm formation of pathogenic E. coli via extracellular activity of DegP. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, C.L.; Isham, N.; Schrom, K.P.; Chandra, J.; McCormick, T.; Miyagi, M.; Ghannoum, M.A. Effects of a Novel Probiotic Combination on Pathogenic Bacterial-Fungal Polymicrobial Biofilms. mBio 2019, 10, e00338-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, D.M.; Pultz, N.J.; Donskey, C.J. Growth in cecal mucus facilitates colonization of the mouse intestinal tract by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, 1621–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pacheco, P.; García-Béjar, B.; Jiménez-Del Castillo, M.; Carreño-Domínguez, J.; Briones Pérez, A.; Arévalo-Villena, M. Potential probiotic and food protection role of wild yeasts isolated from pistachio fruits (Pistacia vera). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupančič, Š.; Škrlec, K.; Kocbek, P.; Kristl, J.; Berlec, A. Effects of Electrospinning on the Viability of Ten Species of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Nanofibers. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Jiang, X.; Xu, X.; Jiang, C.; Kang, R.; Jiang, X. Andrographolide Inhibits Biofilm and Virulence in Listeria monocytogenes as a Quorum-Sensing Inhibitor. Molecules 2022, 27, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, K.; Versalovic, J.; Roos, S.; Britton, R.A. Genomic and genetic characterization of the bile stress response of probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1812–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, A.Y.; Font de Valdez, G.; Fadda, S.; Taranto, M.P. New insights into bacterial bile resistance mechanisms: The role of bile salt hydrolase and its impact on human health. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, A.G.T.; Ramos, C.L.; Cenzi, G.; Melo, D.S.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Probiotic Potential, Antioxidant Activity, and Phytase Production of Indigenous Yeasts Isolated from Indigenous Fermented Foods. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Hidalgo, C.E.; Dorantes-Álvarez, L.; Hernández-Sánchez, H.; Santoyo-Tepole, F.; Martínez-Torres, A.; Villa-Tanaca, L.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Isolation of Yeasts from Guajillo Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Fermentation and Study of Some Probiotic Characteristics. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scillato, M.; Spitale, A.; Mongelli, G.; Privitera, G.F.; Mangano, K.; Cianci, A.; Stefani, S.; Santagati, M. Antimicrobial properties of Lactobacillus cell-free supernatants against multidrug-resistant urogenital pathogens. Microbiol. 2021, 10, e1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.C.; Nardi, R.M.; Bambirra, E.A.; Vieira, E.C.; Nicoli, J.R. Effect of Saccharomyces boulardii against experimental oral infection with Salmonella typhimurium and Shigella flexneri in conventional and gnotobiotic mice. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1996, 81, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Song, Q.; Li, S.; Tu, J.; Yang, F.; Zeng, X.; Yu, H.; Qiao, S.; Wang, G. Protective Role of Indole-3-Acetic Acid Against Salmonella Typhimurium: Inflammation Moderation and Intestinal Microbiota Restoration. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrila, J.; Yang, J.; Crabbé, A.; Sarker, S.F.; Liu, Y.; Ott, C.M.; Nelman-Gonzalez, M.A.; Clemett, S.J.; Nydam, S.D.; Forsyth, R.J.; et al. Three-dimensional organotypic co-culture model of intestinal epithelial cells and macrophages to study Salmonella enterica colonization patterns. npj Microgravity 2017, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothoulakis, C. Review article: Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of action of Saccharomyces boulardii. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumy, K.L.; Chen, X.; Kelly, C.P.; McCormick, B.A. Saccharomyces boulardii interferes with Shigella pathogenesis by postinvasion signaling events. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 294, G599–G609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 909–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, H.; Ahmad, I. Thymus vulgaris essential oil and thymol inhibit biofilms and interact synergistically with antifungal drugs against drug resistant strains of Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis. J. De Mycol. Medicale 2020, 30, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; Abrini, J.; Dakka, N.; Bakri, Y. Essential oils of Origanum compactum increase membrane permeability, disturb cell membrane integrity, and suppress quorum-sensing phenotype in bacteria. J. Pharm. Anal. 2019, 9, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yang, L.; Zou, Y.; Luo, S.; Wang, X.; Liang, Y.; Du, Y.; Feng, R.; Wei, Q. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of three isomeric terpineols of Cinnamomum longepaniculatum leaf oil. Folia Microbiol. 2021, 66, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.; Ramsdale, M. Proteases and caspase-like activity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Lu, W. Biosynthesis of Long-Chain ω-Hydroxy Fatty Acids by Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 4545–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Van’t Klooster, J.S.; Ruiz, S.J.; Poolman, B. Regulation of Amino Acid Transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR 2019, 83, e00024-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Luo, M.; Chen, X.; Yin, Y.; Xiong, X.; Wang, R.; Zhu, Z.J. Ion mobility collision cross-section atlas for known and unknown metabolite annotation in untargeted metabolomics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodkin-Gal, I.; Romero, D.; Cao, S.; Clardy, J.; Kolter, R.; Losick, R. D-amino acids trigger biofilm disassembly. Science 2010, 328, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochbaum, A.I.; Kolodkin-Gal, I.; Foulston, L.; Kolter, R.; Aizenberg, J.; Losick, R. Inhibitory effects of D-amino acids on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 5616–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, A.; Grosjean, H.; Melcher, T.; Keller, W. Tad1p, a yeast tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase, is related to the mammalian pre-mRNA editing enzymes ADAR1 and ADAR2. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 4780–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain * | BY4743 CFS | TAD1-KO CFS | S. boulardii CFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli ATCC25922 | 50.32% ± 0.93% | 11.62% ± 0.64% *** | 36.54% ± 0.47% ** |

| E. coli (mcr-1) 12-2 | 42.29% ± 0.51% | 7.45% ± 0.78% *** | 15.24% ± 0.71% ** |

| S. aureus ATCC29213 | 39.9% ± 1.13% | 7.27% ± 1.31% *** | 40.79% ± 1.1% * |

| S. aureus ATCC25923 | 37.92% ± 0.87% | 5.94% ± 0.98% *** | 38.52% ± 0.33% ns |

| MRSA 1668 | 42.78% ± 0.31% | 8.7% ± 1.17% *** | 37.42% ± 0.29% * |

| P. aeruginosa 1554 | 24.06% ± 0.43% | 1.89% ± 0.67% *** | 23.44% ± 0.54% ns |

| K. pneumoniae 2118 | 26.7% ± 0.73% | 3.77% ± 1.7% *** | 21.31% ± 1.6% * |

| A. baumannii 21-1 | 21.01% ± 0.51% | 1.45% ± 0.59% *** | 2.59% ± 0.98% *** |

| S. typhi SL1344 | 51.33% ± 0.86% | 12.55% ± 1.13% *** | 31.77% ± 0.58% ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Ji, S.; Cong, L.; Mao, S.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Y. Saccharomyces cerevisiae TAD1 Mutant Strain As Potential New Antimicrobial Agent: Studies on Its Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2848. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122848

Zhang Y, Li M, Ji S, Cong L, Mao S, Wang J, Li X, Zhu T, Zhu Z, Li Y. Saccharomyces cerevisiae TAD1 Mutant Strain As Potential New Antimicrobial Agent: Studies on Its Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2848. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122848

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yu, Mengkun Li, Shulei Ji, Liu Cong, Shanshan Mao, Jinyue Wang, Xiao Li, Tao Zhu, Zuobin Zhu, and Ying Li. 2025. "Saccharomyces cerevisiae TAD1 Mutant Strain As Potential New Antimicrobial Agent: Studies on Its Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2848. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122848

APA StyleZhang, Y., Li, M., Ji, S., Cong, L., Mao, S., Wang, J., Li, X., Zhu, T., Zhu, Z., & Li, Y. (2025). Saccharomyces cerevisiae TAD1 Mutant Strain As Potential New Antimicrobial Agent: Studies on Its Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2848. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122848