A Review of Global Patterns in Gut Microbiota Composition, Health and Disease: Locating South Africa in the Conversation

Abstract

1. Introduction

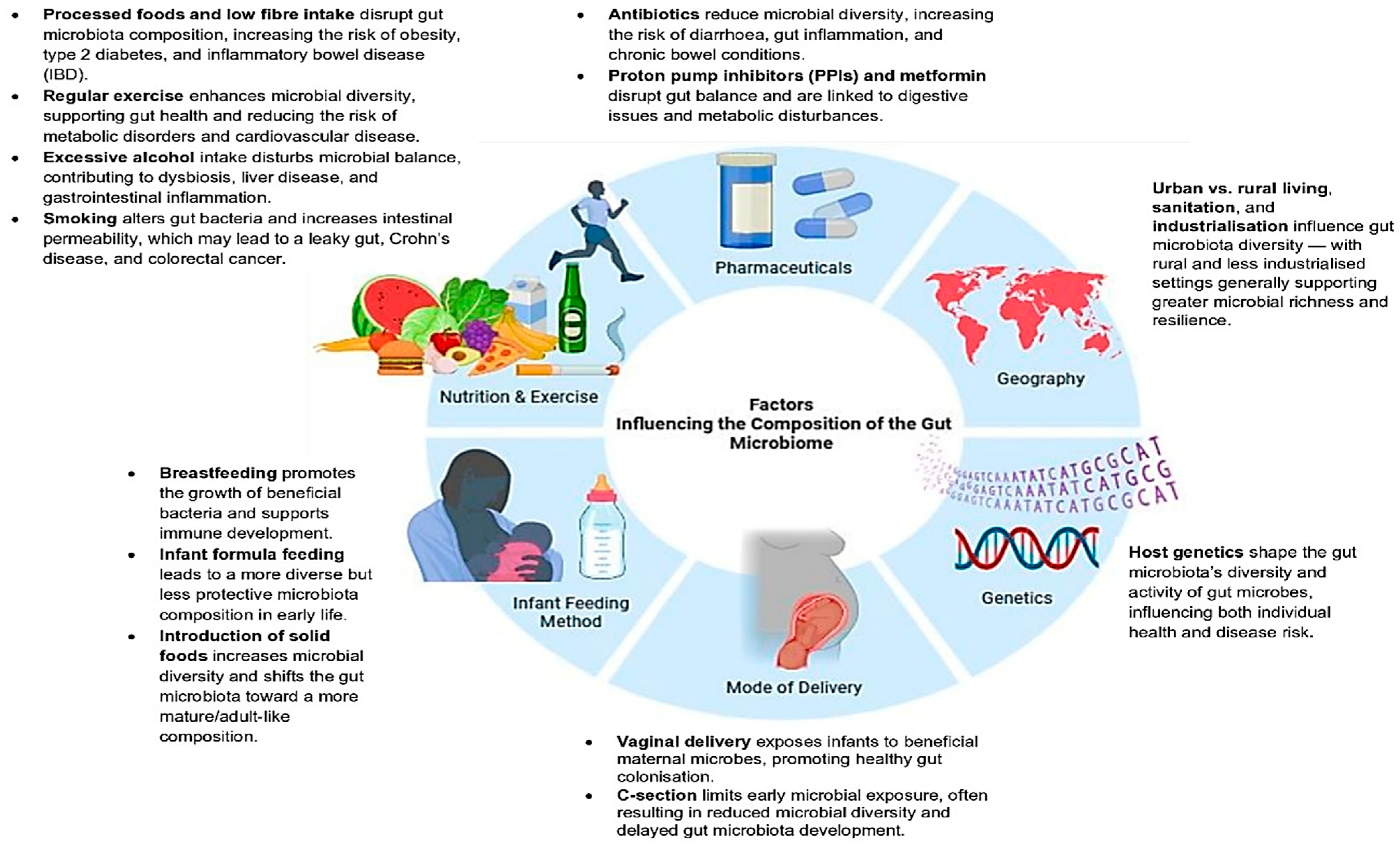

2. From Colonisation to Composition: Factors Shaping Gut Microbial Communities

3. Microbial Diversity Beyond Bacteria: The Neglected Non-Bacterial Constituents of the Gut Microbiome

3.1. Fungi (The Mycobiome): Understudied Immune Modulators

3.2. Viruses (The Virome): An Underexplored Driver of Microbial and Immune Dynamics

3.3. Archaea: Methane Producers and Hydrogen Scavengers

3.4. Protozoa and Helminths: From Pathogens to Partners in Immune Regulation?

3.5. Interactions Between Microbial Components

4. From Harmony to Disruption: The Immunological Cost of Dysbiosis

Defining Dysbiosis and Its Variability

5. The Gut Microbiome of South African Populations in Transition: From Paediatric Research to Emerging Adult Cohorts

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sasso, J.M.; Ammar, R.M.; Tenchov, R.; Lemmel, S.; Kelber, O.; Grieswelle, M.; Zhou, Q.A. Gut microbiome–brain alliance: A landscape view into mental and gastrointestinal health and disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 1717–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.H.H.W. Outnumbered. In The End of Medicine as We Know It—And Why Your Health Has a Future; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, B.; Patel, K.; Lee, C.N.; Moochhala, S. The Microbial Blueprint: The Impact of Your Gut on Your Well-Being; Partridge Publishing: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanaraju, R.; Rao, D.N. The human microbiome: An acquired organ? Resonance 2022, 27, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ahmad, B. Microbiome and its impact on human health: Microbiome in various body organs and its association with human health and disease. In The Microbiome and Cancer: Understanding the Role of Microorganisms in Tumor Development and Treatment; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild, D.; Weissbrod, O.; Barkan, E.; Kurilshikov, A.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Costea, P.I.; Godneva, A.; Kalka, I.N.; Bar, N.; et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 2018, 555, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.S.; Bahl, G.; Mishra, R.; Bhat, A.A.; Thapa, R.; Siddiqui, R.; Sharma, R.; Kulshrestha, R.; Patel, N.; Gupta, G. Introduction to Microbiome. In Gut Microbiome and Environmental Toxicants; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Havulinna, A.S.; Liu, Y.; Jousilahti, P.; Ritchie, S.C.; Tokolyi, A.; Sanders, J.G.; Valsta, L.; Brożyńska, M.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Combined effects of host genetics and diet on human gut microbiota and incident disease in a single population cohort. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 134–142, Correction in Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robitaille, S.; Simmons, E.L.; Verster, A.J.; McClure, E.A.; Royce, D.B.; Trus, E.; Swartz, K.; Schultz, D.; Nadell, C.D.; Ross, B.D. Community composition and the environment modulate the population dynamics of type VI secretion in human gut bacteria. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 2092–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, C.; Duranti, S.; Bottacini, F.; Casey, E.; Turroni, F.; Mahony, J.; Belzer, C.; Delgado Palacio, S.; Arboleya Montes, S.; Mancabelli, L.; et al. The first microbial colonizers of the human gut: Composition, activities, and health implications of the infant gut microbiota. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, e00036-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costea, P.I.; Coelho, L.P.; Sunagawa, S.; Munch, R.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Forslund, K.; Hildebrand, F.; Kushugulova, A.; Zeller, G.; Bork, P. Subspecies in the global human gut microbiome. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2017, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarillo-Guerrero, L.F.; Almeida, A.; Rangel-Pineros, G.; Finn, R.D.; Lawley, T.D. Massive expansion of human gut bacteriophage diversity. Cell 2021, 184, 1098–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.D.; Bisanz, J.E. Challenges and opportunities of strain diversity in gut microbiome research. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1117122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Patangia, D.; Almeida, A.; Zhou, Z.; Mu, D.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C.; Wang, S. A compendium of 32,277 metagenome-assembled genomes and over 80 million genes from the early-life human gut microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, T. Gut microbes may shape response to cancer immunotherapy. JAMA 2018, 319, 430–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Chan, A.T.; Sun, J. Influence of the gut microbiome, diet, and environment on risk of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernroth, M.L.; Peura, S.; Hedman, A.M.; Hetty, S.; Vicenzi, S.; Kennedy, B.; Fall, K.; Svennblad, B.; Andolf, E.; Pershagen, G.; et al. Development of gut microbiota during the first 2 years of life. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.S.; Ijssennagger, N.; Kies, A.K.; van Mil, S.W. Protein fermentation in the gut; implications for intestinal dysfunction in humans, pigs, and poultry. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2018, 315, G159–G170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.T.; Fehlbaum, S.; Seifert, N.; Richard, N.; Bruins, M.J.; Sybesma, W.; Rehman, A.; Steinert, R.E. Effects of colon-targeted vitamins on the composition and metabolic activity of the human gut microbiome—A pilot study. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1875774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Q.; Wang, R.; Thakur, K.; Feng, J.Y.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Zhang, J.G.; Wei, Z.J. Unveiling of dietary and gut-microbiota derived B vitamins: Metabolism patterns and their synergistic functions in gut-brain homeostasis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 4046–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Cheung, C.K.Y.; Lam, K.S.L.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Z.; Ye, D.; Guo, J.; Tse, M.A.; et al. Gut Microbiome Fermentation Determines the Efficacy of Exercise for Diabetes Prevention. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 77–91.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.E.; Kahana, D.D.; Ghuman, S.; Wilson, H.P.; Wilson, J.; Kim, S.C.; Lagishetty, V.; Jacobs, J.P.; Sinha-Hikim, A.P.; Friedman, T.C. Unhealthy lifestyle and gut dysbiosis: A better understanding of the effects of poor diet and nicotine on the intestinal microbiome. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 667066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljumaah, M.R.; Bhatia, U.; Roach, J.; Gunstad, J.; Azcarate Peril, M.A. The gut microbiome, mild cognitive impairment, and probiotics: A randomized clinical trial in middle aged and older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2565–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Qian, L.; Siliceo, S.L.; Long, X.; Nychas, E.; Liu, Y.; Ismaiah, M.J.; Leung, H.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Q.; et al. Resistant starch decreases intrahepatic triglycerides in patients with NAFLD via gut microbiome alterations. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1530–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, N.; Venlet, N.; Hansen, M.L.; Lieberoth, C.B.; Dragsted, L.O.; Bahl, M.I.; Licht, T.R.; Kleerebezem, M.; Lauritzen, L.; Roager, H.M. Effects of a wholegrain-rich diet on markers of colonic fermentation and bowel function and their associations with the gut microbiome: A randomised controlled cross-over trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1187165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Bahl, M.I.; Baunwall, S.M.D.; Hvas, C.L.; Licht, T.R. Determining gut microbial dysbiosis: A review of applied indexes for assessment of intestinal microbiota imbalances. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e00395-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, G.L.V.; Cardoso, C.R.D.B.; Taneja, V.; Fasano, A. Intestinal dysbiosis in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 727485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, B.; Ren, L.; Du, H.; Fei, C.; Qian, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; et al. High-fiber diet ameliorates gut microbiota, serum metabolism and emotional mood in type 2 diabetes patients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1069954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüssow, H. Problems with the concept of gut microbiota dysbiosis. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Zafar, S.; Shahzadi, M.; Sharif, M.; Saeeda, U.H.; Khalid, N.A.; Khan, S. Correlation between gut microbiota and chronic metabolic diseases. In Role of Flavonoids in Chronic Metabolic Diseases: From Bench to Clinic; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- de Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiome and health: Mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littlejohn, P.T.; Glover, J.S. Ethical gut microbiota research in Africa. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 1376–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaboli, M.C.; Ocvirk, S.; Khan Mirzaei, M.; Eberhart, B.L.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.; Metwaly, A.; Neuhaus, K.; Barker, G.; Ru, J.; Nesengani, L.T.; et al. Diet changes due to urbanization in South Africa are linked to microbiome and metabolome signatures of Westernization and colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyo, G.T.; Tepekule, B.; Katsidzira, L.; Blaser, M.J.; Metcalf, C.J.E. Getting ahead of human-associated microbial decline in Africa: The urgency of sampling in light of epidemiological transition. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghini, D.G.; Oduaran, O.H.; Olubayo, L.A.I.; Cook, J.A.; Smyth, N.; Mathema, T.; Belger, C.W.; Agongo, G.; Boua, P.R.; Choma, S.S.; et al. Expanding the human gut microbiome atlas of Africa. Nature 2025, 638, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, R.; Tamburini, F.B.; Asiimwe, E.; Oduaran, O.; Hazelhurst, S.; Bhatt, A.S. Surveying gut microbiome research in Africans: Toward improved diversity and representation. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasolli, E.; Asnicar, F.; Manara, S.; Zolfo, M.; Karcher, N.; Armanini, F.; Beghini, F.; Manghi, P.; Tett, A.; Ghensi, P.; et al. Extensive unexplored human microbiome diversity revealed by over 150,000 genomes from metagenomes spanning age, geography, and lifestyle. Cell 2019, 176, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduaran, O.H.; Tamburini, F.B.; Sahibdeen, V.; Brewster, R.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; Kahn, K.; Norris, S.A.; Tollman, S.M.; Twine, R.; Wade, A.N.; et al. Gut microbiome profiling of a rural and urban South African cohort reveals biomarkers of a population in lifestyle transition. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontaine, F.; Turjeman, S.; Callens, K.; Koren, O. The intersection of undernutrition, microbiome, and child development in the first years of life. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, A.; Petrzelkova, K.J.; Burns, M.B.; Yeoman, C.J.; Amato, K.R.; Vlckova, K.; Modry, D.; Todd, A.; Jost Robinson, C.A.; Remis, M.J.; et al. Gut microbiome of coexisting BaAka Pygmies and Bantu reflects gradients of traditional subsistence patterns. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 2142–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Filippo, C.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Albanese, D.; Pieraccini, G.; Banci, E.; Miglietta, F.; Cavalieri, D.; Lionetti, P. Diet, environments, and gut microbiota. A preliminary investigation in children living in rural and urban Burkina Faso and Italy. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, K.I.; Berry, D.; Wisgrill, L.; Warth, B.; Ezekiel, C.N. Early-life chemical exposome and gut microbiome development: African research perspectives within a global environmental health context. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 30, 1084–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truter, M. The taxonomic diversity of the Ju|’hoansi hunter-gatherer intestinal microbiome in Tsumkwe, Namibia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Alkhatib, D.H.; Feehan, J.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Stojanovska, L. The effect of therapeutic doses of culinary spices in metabolic syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1685, Correction in Nutrients 2024, 16, 3791.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri Soodejani, M. Non-communicable diseases in the world over the past century: A secondary data analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1436236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, H.N.; Charlson, F.; Sorsdahl, K.; Ahmadzada, S.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.; Leung, J.; Santamauro, D.; Lund, C.; Aminde, L.N.; et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1375–e1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.B.; Olivier, S.; Gunda, R.; Koole, O.; Surujdeen, A.; Gareta, D.; Munatsi, D.; Modise, T.H.; Dreyer, J.; Nxumalo, S.; et al. Convergence of infectious and non-communicable disease epidemics in rural South Africa: A cross-sectional, population-based multimorbidity study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e967–e976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achoki, T.; Sartorius, B.; Watkins, D.; Glenn, S.D.; Kengne, A.P.; Oni, T.; Wiysonge, C.S.; Walker, A.; Adetokunboh, O.O.; Babalola, T.K.; et al. Health trends, inequalities and opportunities in South Africa’s provinces, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2022, 76, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.F.; Kassanjee, R.; Folb, N.; Bennett, S.; Boulle, A.; Levitt, N.S.; Curran, R.; Bobrow, K.; Roomaney, R.A.; Bachmann, M.O.; et al. A model-based approach to estimating the prevalence of disease combinations in South Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2024, 9, e013376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modjadji, P. Communicable and non-communicable diseases coexisting in South Africa. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e889–e890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomaney, R.A.; Van Wyk, B.; Cois, A.; Pillay van-Wyk, V. Multimorbidity patterns in South Africa: A latent class analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1082587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owino, V.O. Challenges and opportunities to tackle the rising prevalence of diet-related non-communicable diseases in Africa. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2019, 78, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccacci, F.; Welu, B.; Ndoi, H.; Mosconi, C.; De Santo, C.; Carestia, M.; Altan, A.M.D.; Murungi, J.; Muthuri, K.; Cicala, M.; et al. Exploring diseases burden in HIV population: Results from the CHAO (Comorbidities in HIV/AIDS outpatients) cross-sectional study in Kenya. Glob. Epidemiol. 2024, 8, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, S.; Dengerink, J.; van Vliet, J. Urbanisation as driver of food system transformation and opportunities for rural livelihoods. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 781–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, L.; Hamdan, A.L.; Sataloff, R.T.; Hawkshaw, M.J. Urbanization, transition in diet and voice. In Traits of Civilization and Voice Disorders; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.R.; Begum, M.; Sharmin, R.; Naser, A.Z.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Hossain, M.A.; Tanveer, S.K.M.; Parves, M.M.; Ahmed, E.; Akter, T. Obesity in Southeast Asia: An emerging health concern. Sch. J. Appl. Med. Sci. 2024, 12, 1690–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, I.; Lamiya, U.H.; Rasul, M.G.; Naila, N.N.; Fahim, S.M.; Hasan, S.M.T.; Barratt, M.J.; Gordon, J.I.; Ahmed, T. Development and acceptability of shelf-stable microbiota directed complementary food formulations. Food Nutr. Bull. 2024, 45, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheeha, S.M.; Tamuzi, J.L.; Chale-Matsau, B.; Manda, S.; Nyasulu, P.S. A scoping review evaluating the current state of gut microbiota research in Africa. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, I.; Abotsi, R.E.; Tow, L.A.; Thabane, L.; Zar, H.J.; Mulder, N.M.; Nicol, M.P. Human microbiota research in Africa: A systematic review reveals gaps and priorities for future research. Microbiome 2021, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, R.; Boucher, K.; Lavelle, A.; Arumugam, M.; Blaser, M.J.; Claesson, M.J.; Clarke, G.; Cotter, P.D.; De Sordi, L.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; et al. Examining the healthy human microbiome concept. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 192–205, Correction in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienaber-Rousseau, C. Understanding and applying gene–environment interactions: A guide for nutrition professionals with an emphasis on integration in African research settings. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e443–e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkera-Gutabara, C.K.; Kerr, R.; Scholefield, J.; Hazelhurst, S.; Naidoo, J. Microbiomics: The next pillar of precision medicine and its role in African healthcare. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 869610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouidhi, S.; Oduaran, O.H. Strengthening the foundation of African microbiome research: Strategies for standardized data collection. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 742–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuik, F.E.R.; Dicksved, J.; Lam, S.Y.; Fuhler, G.M.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; van de Winkel, A.; Konstantinov, S.R.; Spaander, M.C.W.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Engstrand, L.; et al. Composition of the mucosa-associated microbiota along the entire gastrointestinal tract of human individuals. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P.; Adhikary, K.; Chatterjee, A.; Sarkar, R.; Bagchi, D.; Ghosh, N.; Das, A. Digestion and gut microbiome. In Nutrition and Functional Foods in Boosting Digestion, Metabolism and Immune Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Passos, M.D.C.F.; Moraes-Filho, J.P. Intestinal microbiota in digestive diseases. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2017, 54, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selma-Royo, M.; Calatayud Arroyo, M.; García-Mantrana, I.; Parra-Llorca, A.; Escuriet, R.; Martínez-Costa, C.; Collado, M.C. Perinatal environment shapes microbiota colonization and infant growth: Impact on host response and intestinal function. Microbiome 2020, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillman, E.T.; Lu, H.; Yao, T.; Nakatsu, C.H. Microbial ecology along the gastrointestinal tract. Microbes Environ. 2017, 32, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E.M. Gut bacteria in health and disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 9, 560. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Martínez, C.; Santaella-Pascual, M.; Yagüe-Guirao, G.; Martínez-Graciá, C. Infant gut microbiota colonization: Influence of prenatal and postnatal factors, focusing on diet. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1236254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkoporov, A.N.; Turkington, C.J.; Hill, C. Mutualistic interplay between bacteriophages and bacteria in the human gut. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.A.; Fitzstevens, J.L.; Schmidt, V.T.; Enav, H.; Huus, K.E.; Mbong Ngwese, M.; Grießhammer, A.; Pfleiderer, A.; Adegbite, B.R.; Zinsou, J.F.; et al. Codiversification of gut microbiota with humans. Science 2022, 377, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, W.T.; Dudaniec, R.Y.; Kleindorfer, S.; Cavanaugh, C.M. An inter-island comparison of Darwin’s finches reveals the impact of habitat, host phylogeny, and island on the gut microbiome. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kijner, S.; Kolodny, O.; Yassour, M. Human milk oligosaccharides and the infant gut microbiome from an eco-evolutionary perspective. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 68, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korpela, K. Impact of delivery mode on infant gut microbiota. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 77, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raspini, B.; Vacca, M.; Porri, D.; De Giuseppe, R.; Calabrese, F.M.; Chieppa, M.; Liso, M.; Cerbo, R.M.; Civardi, E.; Garofoli, F.; et al. Early life microbiota colonization at six months of age: A transitional time point. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 590202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhav, L.; Fehr, K.; Reyna, M.E.; Petersen, C.; Dai, D.L.; Dai, R.; Breton, V.; Rossi, L.; Smieja, M.; Simons, E.; et al. Microbial colonization programs are structured by breastfeeding and guide healthy respiratory development. Cell 2024, 187, 5431–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.A.; Li, J.P.; Lee, M.S.; Yang, S.F.; Chang, Y.S.; Chen, L.; Li, C.W.; Chao, Y.H. A common trajectory of gut microbiome development during the first month in healthy neonates with limited inter-individual environmental variations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naspolini, N.F.; Natividade, A.P.; Asmus, C.I.F.; Moreira, J.C.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Meyer, A. Early-life gut microbiome is associated with behavioral disorders in the Rio birth cohort. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Mahurkar, A.; Rahnavard, G.; Crabtree, J.; Orvis, J.; Hall, A.B.; Brady, A.; Creasy, H.H.; McCracken, C.; Giglio, M.G.; et al. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature 2017, 550, 61–66, Correction in Nature 2017, 551, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuoka, T. Intestinal flora and aging. Nutr. Rev. Wash. 1992, 50, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodmansey, E.J. Intestinal bacteria and ageing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastyk, H.C.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Perelman, D.; Dahan, D.; Merrill, B.D.; Yu, F.B.; Topf, M.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Van Treuren, W.; Han, S.; et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell 2021, 184, 4137–4153.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Qian, L.; He, J.; Ni, Y.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Yuan, R.; Liu, S.; et al. Resistant starch intake facilitates weight loss in humans by reshaping the gut microbiota. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeMay-Nedjelski, L.; Butcher, J.; Ley, S.H.; Asbury, M.R.; Hanley, A.J.; Kiss, A.; Unger, S.; Copeland, J.K.; Wang, P.W.; Zinman, B.; et al. Examining the relationship between maternal body size, gestational glucose tolerance status, mode of delivery and ethnicity on human milk microbiota at three months post-partum. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, S.E.; Hullar, M.A.J.; Tritchler, D.L.; Cortes-Gomez, E.; Yao, S.; Davis, W.; O’Connor, T.; Erwin, D.; Thompson, L.U.; Yan, L.; et al. Enterolignan production in a flaxseed intervention study in postmenopausal US women of African ancestry and European ancestry. Nutrients 2021, 13, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschasaux, M.; Bouter, K.E.; Prodan, A.; Levin, E.; Groen, A.K.; Herrema, H.; Tremaroli, V.; Bakker, G.J.; Attaye, I.; Pinto-Sietsma, S.J.; et al. Depicting the composition of gut microbiota in a population with varied ethnic origins but shared geography. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1526–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwiyanto, J.; Hussain, M.H.; Reidpath, D.; Ong, K.S.; Qasim, A.; Lee, S.W.H.; Lee, S.M.; Foo, S.C.; Chong, C.W.; Rahman, S. Ethnicity influences the gut microbiota of individuals sharing a geographical location: A cross-sectional study from a middle-income country. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, J.A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Deschasaux, M.; Radjabzadeh, D.; Kraaij, R.; Davids, M.; de Rooij, S.R.; Lok, A. The gut microbiota and depressive symptoms across ethnic groups. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niccolai, E.; Di Gloria, L.; Trolese, M.C.; Fabbrizio, P.; Baldi, S.; Nannini, G.; Margotta, C.; Nastasi, C.; Ramazzotti, M.; Bartolucci, G.; et al. Host genetics and gut microbiota influence lipid metabolism and inflammation: Potential implications for ALS pathophysiology in SOD1G93A mice. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 174, Correction in Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A.K.; Kelly, S.A.; Legge, R.; Ma, F.; Low, S.J.; Kim, J.; Zhang, M.; Oh, P.L.; Nehrenberg, D.; Hua, K.; et al. Individuality in gut microbiota composition is a complex polygenic trait shaped by multiple environmental and host genetic factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18933–18938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhernakova, D.V.; Wang, D.; Liu, L.; Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ruiz-Moreno, A.J.; Peng, H.; Plomp, N.; Del Castillo-Izquierdo, Á.; Gacesa, R.; et al. Host genetic regulation of human gut microbial structural variation. Nature 2024, 625, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.M.; Breed, M.F. Beyond microbial exposure and colonization: Multisensory shaping of the gut microbiome. mSystems 2025, 10, e01107-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S. Factors influencing development of the infant microbiota: From prenatal period to early infancy. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 65, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogoş, G.F.R.; Manciulea, M.; Enache, R.M.; Pavelescu, L.A.; Popescu, O.A.; Cretoiu, S.M.; Marinescu, I. Intestinal microbiota in early life: Latest findings regarding the role of probiotics as a treatment approach for dysbiosis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliev, I.D.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Guo, C.J. Microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease: Mechanisms of disease and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, J.; Ni, Q.; Sun, W.; Li, L.; Feng, X. The links between gut microbiota and obesity and obesity related diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 147, 112678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Qu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, S.; Wu, R.; Wu, J. Research progress on the correlation between the intestinal microbiota and food allergy. Foods 2022, 11, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fan, N.; Ma, S.X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, G. Gut microbiota dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, diseases, prevention, and therapy. MedComm 2025, 6, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xie, P. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in depression: From pathogenesis to treatment. eBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.C. Fungi of the human gut microbiota: Roles and significance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 311, 151490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limon, J.J.; Skalski, J.H.; Underhill, D.M. Commensal fungi in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, M.L.; Sokol, H. The gut mycobiota: Insights into analysis, environmental interactions and role in gastrointestinal diseases. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moissl-Eichinger, C.; Pausan, M.; Taffner, J.; Berg, G.; Bang, C.; Schmitz, R.A. Archaea are interactive components of complex microbiomes. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkoporov, A.N.; Hill, C. Bacteriophages of the human gut: The “known unknown” of the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, A.C.; Zablocki, O.; Zayed, A.A.; Howell, A.; Bolduc, B.; Sullivan, M.B. The gut virome database reveals age-dependent patterns of virome diversity in the human gut. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 724–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, W.; He, F.; Li, J. The mycobiome as integral part of the gut microbiome: Crucial role of symbiotic fungi in health and disease. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2440111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, A.K.; Auchtung, T.A.; Wong, M.C.; Smith, D.P.; Gesell, J.R.; Ross, M.C.; Stewart, C.J.; Metcalf, G.A.; Muzny, D.M.; Gibbs, R.A.; et al. The gut mycobiome of the Human Microbiome Project healthy cohort. Microbiome 2017, 5, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherden, E.A.; Shoaie, S.; Hall, R.A.; Moyes, D.L. The human mucosal mycobiome and fungal community interactions. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallen-Adams, H.E.; Suhr, M.J. Fungi in the healthy human gastrointestinal tract. Virulence 2017, 8, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xia, Y.; He, F.; Zhu, C.; Ren, W. Intestinal mycobiota in health and diseases: From a disrupted equilibrium to clinical opportunities. Microbiome 2021, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.; Penders, J.; Venema, K. Fungal-bacterial interactions in the human gut of healthy individuals. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitan, M.; Niemiec, M.J.; Steimle, A.; Frick, J.S.; Jacobsen, I.D. Fungi as part of the microbiota and interactions with intestinal bacteria. In Fungal Physiology and Immunopathogenesis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 265–301. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Gao, W.-Q.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, X.; Chu, H. Gut non-bacterial microbiota: Emerging link to irritable bowel syndrome. Toxins 2022, 14, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.A.; Mahmoud, M.M.; Abd El-Rahman, G.I. Gut microbiota alterations in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. Arab J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 23, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Haak, B.W.; Lankelma, J.M.; Hugenholtz, F.; Belzer, C.; de Vos, W.M.; Wiersinga, W.J.; Nieuwdorp, M. Longitudinal impact of antimicrobial therapy on the gut microbiome in critically ill patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 246–256. [Google Scholar]

- Nel Van Zyl, K.; Whitelaw, A.C.; Hesseling, A.C.; Seddon, J.A.; Demers, A.M.; Newton-Foot, M. Fungal diversity in the gut microbiome of young South African children. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabwe, M.H.; Vikram, S.; Mulaudzi, K.; Jansson, J.K.; Makhalanyane, T.P. The gut mycobiota of rural and urban individuals is shaped by geography. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S.; Durairajan, S.S.K.; Singh, A.K.; Krishnamoorthi, S.; Iyaswamy, A.; Mandavi, S.P.; Jeewon, R.; Williams, L.L. Role of Candida species in pathogenesis, immune regulation, and prognostic tools for managing ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 5212–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawhara, S. Healthy diet and lifestyle improve the gut microbiota and help combat fungal infection. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.M.; Allen-Vercoe, E. Phage-host interactions in the gut: Influence of temperate bacteriophages on the gut microbiome. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 927–935. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan-Nash, A.D.; Korry, B.J.; Mylonakis, E.; Belenky, P. Cross-domain and viral interactions in the microbiome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019, 83, e00044-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathakumari, R.H.; Vajravelu, L.K.; Gopinathan, A.; Vimala, P.B.; Panneerselvam, V.; Ravi, S.S.S.; Thulukanam, J. The gut virome and human health: From diversity to personalized medicine. Eng. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetta, H.F.; Ahmed, R.; Ramadan, Y.N.; Fathy, H.; Khorshid, M.; Mabrouk, M.M.; Hashem, M. Gut virome: New key players in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Methodol. 2025, 15, 92592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cheng, R.; Lin, H.; Li, L.; Jia, Y.; Philips, A.; Zuo, T.; Zhang, H. Gut virome and its implications in the pathogenesis and therapeutics of inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavkare, A.M.; Nanaware, N.L.; Sonar, M.N.; Dhotre, S.V.; Mumbre, S.S.; Nagoba, B.S. Gut microbiome and viral infections: A hidden nexus for immune protection. World J. Virol. 2025, 14, 111912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukadida, C.; Peralta-Prado, A.; Chávez-Torres, M.; Romero-Mora, K.; Rincon-Rubio, A.; Ávila-Ríos, S.; Garrido-Rodríguez, D.; Reyes-Terán, G.; Pinto-Cardoso, S. Alterations of the gut microbiome in HIV infection highlight human anelloviruses as potential predictors of immune recovery. Microbiome 2024, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, C.L.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Zhao, G.; Handley, S.A.; Ghebremichael, M.S.; Lim, E.S.; Lankowski, A.; Baldridge, M.T.; Wilen, C.B.; Flagg, M.; et al. Altered virome and bacterial microbiome in human immunodeficiency virus-associated acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, F.B.; Maghini, D.; Oduaran, O.H.; Brewster, R.; Hulley, M.R.; Sahibdeen, V.; Norris, S.A.; Tollman, S.; Kahn, K.; Wagner, R.G.; et al. Short-and long-read metagenomics of urban and rural South African gut microbiomes reveal a transitional composition and undescribed taxa. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babkin, I.V.; Fedorets, V.A.; Tikunov, A.Y.; Baykov, I.K.; Panina, E.A.; Tikunova, N.V. Zeta CrAss-like Phages, a Separate Phage Family Using a Variety of Adaptive Mechanisms to Persist in Their Hosts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.A.; Vega, A.A.; Norman, H.M.; Ohaeri, M.; Levi, K.; Dinsdale, E.A.; Cinek, O.; Aziz, R.K.; McNair, K.; Barr, J.J.; et al. Global phylogeography and ancient evolution of the widespread human gut virus crAssphage. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Wen, Z.; Liu, W.; Meng, L.; Huang, H. Oscillospira—A candidate for the next-generation probiotics. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1987783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.T.; Shen, S.J.; Liao, K.F.; Huang, C.Y. Dietary plant and animal protein sources oppositely modulate fecal Bilophila and Lachnoclostridium in vegetarians and omnivores. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02047-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yu, J. The association of diet, gut microbiota and colorectal cancer: What we eat may imply what we get. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; AT, R.; Adhikary, S.; Banerjee, A.; Radhakrishnan, A.K.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Pathak, S. Exploring the relationship between diet, lifestyle and gut microbiome in colorectal cancer development: A recent update. Nutr. Cancer 2024, 76, 789–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogotsi, M.T.; Ogunbayo, A.E.; Bester, P.A.; O’Neill, H.G.; Nyaga, M.M. Longitudinal analysis of the enteric virome in paediatric subjects from the Free State Province, South Africa, reveals early gut colonisation and temporal dynamics. Virus Res. 2024, 346, 199403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokorogu, V.C.; Pillai, S.; San, J.E.; Pillay, C.; Nyaga, M.M.; Sabiu, S. A metagenomic investigation of the faecal RNA virome structure of asymptomatic chickens obtained from a commercial farm in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.P.; San, J.E.; Gordon, M.L. Metagenomic analysis of RNA fraction reveals the diversity of swine oral virome on South African backyard swine farms in the uMgungundlovu district of KwaZulu-Natal province. Pathogens 2022, 11, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dridi, B.; Henry, M.; El Khechine, A.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. High prevalence of Methanobrevibacter smithii and Methanosphaera stadtmanae detected in the human gut using an improved DNA detection protocol. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7063. [Google Scholar]

- Blais Lecours, P.; Marsolais, D.; Cormier, Y.; Berberi, M.; Haché, C.; Bourdages, R.; Duchaine, C. Increased prevalence of Methanosphaera stadtmanae in inflammatory bowel diseases. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87734. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegenauer, C.; Hammer, H.F.; Mahnert, A.; Moissl-Eichinger, C. Methanogenic archaea in the human gastrointestinal tract. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaci, N.; Borrel, G.; Tottey, W.; O’Toole, P.W.; Brugère, J.F. Archaea and the human gut: New beginning of an old story. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2014, 20, 16062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezani, A.; Nolin, T.D.; Barrows, I.R.; Serrano, M.G.; Buck, G.A.; Regunathan-Shenk, R.; West, R.E., III; Latham, P.S.; Amdur, R.; Raj, D.S. Gut colonization with methanogenic archaea lowers plasma trimethylamine N-oxide concentrations in apolipoprotein e−/− mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, A.; Lee, J.K.Y.; Gounot, J.S.; Ravikrishnan, A.; Ding, Y.; Saw, W.Y.; Tan, L.W.L.; Moong, D.K.N.; Teo, Y.Y.; Nagarajan, N.; et al. Mutual exclusion of Methanobrevibacter species in the human gut microbiota facilitates directed cultivation of a Candidatus Methanobrevibacter intestini representative. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00849-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, M.; Tang, X. Human archaea and associated metabolites in health and disease. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 2835–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, C.; Dollive, S.; Grunberg, S.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Wu, G.D.; Lewis, J.D.; Bushman, F.D. Archaea and fungi of the human gut microbiome: Correlations with diet and bacterial residents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66019. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed, R.; Valcheva, R.; Dieleman, L.A. Manipulation of gut microbiota as a key target for Crohn’s disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 887044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghavami, S.B.; Rostami, E.; Sephay, A.A.; Shahrokh, S.; Balaii, H.; Aghdaei, H.A.; Zali, M.R. Alterations of the human gut Methanobrevibacter smithii as a biomarker for inflammatory bowel diseases. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 117, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.F. Syntrophic imbalance and the etiology of bacterial endoparasitism diseases. Med. Hypotheses 2017, 107, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrnreiter, C.J.; Murray, M.G.; Luck, M.; Ganesa, C.; Kuprys, P.V.; Li, X.; Choudhry, M.A. Bacterial dysbiosis and decrease in SCFA correlate with intestinal inflammation following alcohol intoxication and burn injury. eGastroenterology 2025, 3, e100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpitsch, C.; Fischmeister, F.P.h.S.; Mahnert, A.; Lackner, S.; Wilding, M.; Sturm, C.; Springer, A.; Madl, T.; Holasek, S.; Högenauer, C.; et al. Reduced B12 uptake and increased gastrointestinal formate are associated with archaeome-mediated breath methane emission in humans. Microbiome 2021, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, R.; Mahnert, A.; Shinde, T.; Kumpitsch, C.; Weinberger, V.; Schmidt, H.; Moissl-Eichinger, C. Age-related dynamics of predominant methanogenic archaea in the human gut microbiome. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgler, E.; Baumgartner, M.; Duller, S.; Kumptisch, C.; Hausmann, B.; Moser, D.; Khare, V.; Lang, M.; Köcher, T.; Frick, A.; et al. Archaea influence composition of endoscopically visible ileocolonic biofilms. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2359500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianiro, G.; Iorio, A.; Porcari, S.; Masucci, L.; Sanguinetti, M.; Perno, C.F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Putignani, L.; Cammarota, G. How the gut parasitome affects human health. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2022, 15, 17562848221091524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Waters, A.K.; Basalirwa, G.; Ssetaala, A.; Mpendo, J.; Namuniina, A.; Keneema, E.; Kiiza, D.; Kyosiimire-Lugemwa, J.; Mayanja, Y.; et al. Impact of Schistosoma mansoni Infection on the Gut Microbiome and Hepatitis B Vaccine Immune Response in Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Vaccines 2025, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieves-Ramírez, M.E.; Partida-Rodríguez, O.; Laforest-Lapointe, I.; Reynolds, L.A.; Brown, E.M.; Valdez-Salazar, A.; Morán-Silva, P.; Rojas-Velázquez, L.; Morien, E.; Parfrey, L.W.; et al. Asymptomatic intestinal colonization with protist Blastocystis is strongly associated with distinct microbiome ecological patterns. Msystems 2018, 3, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audebert, C.; Even, G.; Cian, A.; Loywick, A.; Merlin, S.; Viscogliosi, E.; Chabé, M. Colonization with the enteric protozoa Blastocystis is associated with increased diversity of human gut bacterial microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien Andersen, L.; Karim, A.B.; Roager, H.M.; Vigsnæs, L.K.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Licht, T.R.; Stensvold, C.R. Associations between common intestinal parasites and bacteria in humans as revealed by qPCR. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 35, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghini, F.; Pasolli, E.; Truong, T.D.; Putignani, L.; Cacciò, S.M.; Segata, N. Large-scale comparative metagenomics of Blastocystis, a common member of the human gut microbiome. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2848–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeleke, O.A.; Yogeswaran, P.; Wright, G. Intestinal helminth infections amongst HIV-infected adults in Mthatha General Hospital, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2015, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mkhize-Kwitshana, Z.L.; Tadokera, R.; Mabaso, M.H. Helminthiasis: A systematic review of the immune interactions present in individuals coinfected with HIV and/or tuberculosis. In Human Helminthiasis; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Mpaka-Mbatha, M.N.; Naidoo, P.; Islam, M.M.; Singh, R.; Mkhize-Kwitshana, Z.L. Demographic profile of HIV and helminth-coinfected adults in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 38, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabé, M.; Certad, G.; Caccio, S.M. Enteric unicellular eukaryotic parasites and gut microbiota: Mechanisms and mcology. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 779412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforest-Lapointe, I.; Arrieta, M.C. Microbial eukaryotes: A missing link in gut microbiome studies. mSystems 2018, 3, e00201-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukeš, J.; Stensvold, C.R.; Jirků-Pomajbíková, K.; Wegener Parfrey, L. Are human intestinal eukaryotes beneficial or commensals? PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, P.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: Intestinal pathogenesis mechanisms and colonization resistance by gut microbiota. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2055943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausset, R.; Petit, M.A.; Gaboriau-Routhiau, V.; De Paepe, M. New insights into intestinal phages. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 205–215, Correction in Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 559.. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhya, I.; Segal, J.P.; Carding, S.R.; Hart, A.L.; Hold, G.L. The gut virome: The ‘missing link’ between gut bacteria and host immunity? Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2019, 12, 1756284819836620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhong, L.; Wu, J.; Zeng, G.; Liu, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, M. Modulation of gut mycobiome and serum metabolome by a MUFA-rich diet in Sprague Dawley rats fed a high-fructose, high-fat diet. Foods 2025, 14, 506. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, E.M.; Ramay, H.R.; Moossavi, S.; Laforest-Lapointe, I.; Reyna, M.E.; Becker, A.B.; Simons, E.; Mandhane, P.J.; Turvey, S.E.; Moraes, T.J.; et al. Divergent maturational patterns of the infant bacterial and fungal gut microbiome in the first year of life are associated with inter-kingdom community dynamics and infant nutrition. Microbiome 2024, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Bandera, A.; Gori, A. Therapeutic potential of the gut microbiota in the management of sepsis. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubatan, J.; Holman, D.R.; Puntasecca, C.J.; Polevoi, D.; Rubin, S.J.; Rogalla, S. Antimicrobial peptides and the gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Barreiro, L.; Zhang, L.; Abdel-Rahman, S.A.; Naik, S.P.; Gabr, M. Gut microbial-derived metabolites as immune modulators of T helper 17 and regulatory T cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, C.; Kandalgaonkar, M.R.; Golonka, R.M.; Yeoh, B.S.; Vijay-Kumar, M.; Saha, P. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and host immunity: Impact on inflammation and immunotherapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Zheng, Y.; Elsabagh, M.; Fan, K.; Zha, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H. Gut microbiota modulate intestinal inflammation by endoplasmic reticulum stress-autophagy-cell death signaling axis. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Diwan, M.; Lahimer, M.; Bach, V.; Gosselet, F.; Khorsi-Cauet, H.; Candela, P. Impact of pesticide residues on the gut-microbiota–blood–brain barrier Axis: A narrative review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6147. [Google Scholar]

- Alagiakrishnan, K.; Morgadinho, J.; Halverson, T. Approach to the diagnosis and management of dysbiosis. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1330903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczyńska, J.; Kowalczyk, M. The potential of short-chain fatty acid epigenetic regulation in chronic low-grade inflammation and obesity. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1380476. [Google Scholar]

- Bolte, L.A.; Vila, A.V.; Imhann, F.; Collij, V.; Gacesa, R.; Peters, V.; Wijmenga, C.; Kurilshikov, A.; Campmans-Kuijpers, M.J.; Fu, J.; et al. Long-term dietary patterns are associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory features of the gut microbiome. Gut 2021, 70, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetta, H.F.; Ramadan, Y.N.; Alharbi, A.A.; Alsharef, S.; Alkindy, T.T.; Alkhamali, A.; Albalawi, A.S.; El Amin, H. Gut microbiome as a target of intervention in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis and therapy. Immuno 2024, 4, 400–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, N.; Geesala, R.; Shi, X.Z. Gut microbial metabolite butyrate and its therapeutic role in inflammatory bowel disease: A literature review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, V.K.; George, M. A review of the contribution of gut-dependent microbiota derived marker, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), in coronary artery disease. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2021, 9, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawhara, S. How gut bacterial dysbiosis can promote Candida albicans overgrowth during colonic inflammation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.; Kruithoff, C.; San Valentin, E.M.; Gamal, A.; McCormick, T.S.; Ghannoum, M. Small Intestinal Bacterial and Fungal Overgrowth: Health Implications and Management Perspectives. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtman, T.A.; Eckermann, H.A.; Smidt, H.; de Weerth, C. Gut microbiota and BMI throughout childhood: The role of firmicutes, bacteroidetes, and short-chain fatty acid producers. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karačić, A.; Renko, I.; Krznarić, Ž.; Klobučar, S.; Liberati Pršo, A.M. The Association between the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio and Body Mass among European Population with the Highest Proportion of Adults with Obesity: An Observational Follow-Up Study from Croatia. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mthombeni, T.C.; Burger, J.R.; Lubbe, M.S.; Julyan, M. Antibiotic consumption in the public sector of the Limpopo province, South Africa, 2014–2018. S. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 37, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Cronjé, H.T.; Van Zyl, T.; Bondonno, N.; Pieters, M. The association between an energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index and inflammation in rural and urban Black South Africans. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 3432–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkambule, S.J.; Moodley, I.; Kuupiel, D.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.P. Association between food insecurity and key metabolic risk factors for diet-sensitive non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toor, D.; Wasson, M.K.; Kumar, P.; Karthikeyan, G.; Kaushik, N.K.; Goel, C.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A.; Prakash, H. Dysbiosis disrupts gut immune homeostasis and promotes gastric diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaledi, M.; Poureslamfar, B.; Alsaab, H.O.; Tafaghodi, S.; Hjazi, A.; Singh, R.; Alawadi, A.H.; Alsaalamy, A.; Qasim, Q.A.; Sameni, F. The role of gut microbiota in human metabolism and inflammatory diseases: A focus on elderly individuals. Ann. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, S.; Das, A. Exploring the complex and multifaceted interplay of the gut microbiome and cancer prevention and therapy. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2023, 70, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D.; Petitfils, C.; De Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; El-Omar, E.M. What defines a healthy gut microbiome? Gut 2024, 73, 1893–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farup, P.G.; Aasbrenn, M.; Valeur, J. Separating “good” from “bad” faecal dysbiosis-evidence from two cross-sectional studies. BMC Obes. 2018, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Zogg, H.; Wei, L.; Bartlett, A.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Rajender, S.; Ro, S. Gut microbial dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal dysmotility and metabolic disorders. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 27, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, M. The effects of metformin on gut microbiota and the immune system as research frontiers. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1662–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Chen, J.; Meng, Y.; Yang, J.; Cui, Q.; Zhou, Y. Metformin alters gut microbiota of healthy mice: Implication for its potential role in gut microbiota homeostasis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Kamyshna, I.; Oksenych, V.; Kainov, D.; Kamyshnyi, A. Metformin therapy changes gut microbiota alpha-diversity in COVID-19 patients with type 2 diabetes: The role of SARS-CoV-2 variants and antibiotic treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo, D.; Méndez-García, C.; Raczkowska, B.A.; Bargiela, R.; Moya, A.; Ferrer, M.; Barbas, C. Exploring the human microbiome from multiple perspectives: Factors altering its composition and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Menon, N.; Lim, C.T. Dissecting gut-microbial community interactions using a gut microbiome-on-a-chip. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2302113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuddenham, S.; Sears, C.L. The intestinal microbiome and health. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 28, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.; Mutesa, L.; Tindana, P.; Ramsay, M. African genetic diversity and adaptation inform a precision medicine agenda. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021, 22, 284–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostal, A.; Baumgartner, J.; Riesen, N.; Chassard, C.; Smuts, C.M.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Lacroix, C. Effects of iron supplementation on dominant bacterial groups in the gut, faecal SCFA and gut inflammation: A randomised, placebo-controlled intervention trial in South African children. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavinia, M.; Rasmussen, H.E.; Engen, P.; Van den Berg, J.P.; Davis, E.; Engen, K.; Green, S.J.; Naqib, A.; Botha, M.; Gray, C.; et al. Atopic dermatitis and food sensitization in South African toddlers: Role of fiber and gut microbiota. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017, 118, 742–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claassen-Weitz, S.; Gardner-Lubbe, S.; Nicol, P.; Botha, G.; Mounaud, S.; Shankar, J.; Nierman, W.C.; Mulder, N.; Budree, S.; Zar, H.J.; et al. HIV-exposure, early life feeding practices and delivery mode impacts on faecal bacterial profiles in a South African birth cohort. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Niekerk, M.; Dunbar, R.; Benycoub, J.; Grathwohl, D.; Labadarios, D. Microbiota Richness and Diversity in a Cohort of Underweight HIV-Positive Children Aged 24–72 Months in Cape Town, South Africa. HIV Med. 2019, 20, 317–337. [Google Scholar]

- Budree, S.; Osman, M.; Nduru, P.; Kaba, M.; Zellmer, C.; Claasens, S.; Zar, H. Evaluating the gut microbiome in children with stunting: Findings from a South African birth cohort. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 99, 198–199. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Coetzee, V.; Kruger, J.; Potgieter, H.; Buys, E.M. Dysbiosis signatures of fecal microbiota in South African infants with respiratory, gastrointestinal, and other diseases. J. Pediatr. 2020, 218, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosen, C.; Proost, S.; Baumgartner, J.; Mallick, K.; Tito, R.Y.; Barnabas, S.L.; Cotton, M.F.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Raes, J.; Blaauw, R. Associations of HIV and iron status with gut microbiota composition, gut inflammation and gut integrity in South African school-age children: A two-way factorial case-control study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, K.; Whitelaw, A.C.; Hesseling, A.C.; Seddon, J.A.; Demers, A.M.; Newton-Foot, M. Association between clinical and environmental factors and the gut microbiota profiles in young South African children. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallenborn, J.T.; Gunier, R.B.; Pappas, D.J.; Chevrier, J.; Eskenazi, B. Breastmilk, Stool, and Meconium: Bacterial Communities in South Africa. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 83, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, N.; Bernabé, B.P.; Lie, L.; Baghdan, D.; Bedu-Addo, K.; Plange-Rhule, J.; Forrester, T.E.; Lambert, E.V.; Bovet, P.; Gottel, N.; et al. The human microbiota is associated with cardiometabolic risk across the epidemiologic transition. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Long, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, L.; Hamaker, B.R. Fiber-utilizing capacity varies in Prevotella-versus Bacteroides-dominated gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartsch, M.; Vital, M.; Woltemate, S.; Bouwman, F.G.; Berkemeyer, S.B.; Hahn, A.; Müller, M. Microbiota-dependent fiber responses: A proof-of-concept study on short-chain fatty acid production in Prevotella-and Bacteroides-dominated healthy individuals. J. Nutr. 2025, 155, 3809–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, A.; Clinger, E.; Hao, L. Effect of diet and dietary components on the composition of the gut microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.; Rubbino, F.; Ferrari, C.; Michela, C.; Grizzi, F.; Bonelli, F.; Malesci, A.; Mazzone, M.; Ricciardiello, L.; Laghi, L. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with colorectal cancer molecular subtypes and its outcome. A systematic review. Gut Microbiome 2025, 6, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunizeau, C.; Franck, M.; Boutin, A.; Ruel, M.; Poliakova, N.; Ayotte, P.; Bélanger, R. The gut microbiota of Indigenous populations in the context of dietary westernization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1652598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetta, H.F.; Sirag, N.; Elfadil, H.; Salama, A.; Aljadrawi, S.F.; Alfaifi, A.J.; Alwabisi, A.N.; AbuAlhasan, B.M.; Alanazi, L.S.; Aljohani, Y.A.; et al. Artificial sweeteners: A double-edged sword for gut microbiome. Diseases 2025, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, F.C.; Patangia, D.; Grimaud, G.; Lavelle, A.; Dempsey, E.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. The interplay between diet and the gut microbiome: Implications for health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.; Mann, J.; Cummings, J.; Winter, N.; Mete, E.; Te Morenga, L. Carbohydrate quality and human health: A series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet 2019, 393, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, J.A.; Choo-Kang, C.; Wang, L.; Issa, L.; Gilbert, J.A.; Ecklu-Mensah, G.; Luke, A.; Bedu-Addo, K.; Forrester, T.; Bovet, P.; et al. Toxic metals impact gut microbiota and metabolic risk in five African-origin populations. Gut Microbes Rep. 2025, 2, 2481442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microbial Group | Typical Abundance | Dominant Genera | Core Functional Roles | Associated Disease Outcomes | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi (Mycobiome) | Low relative abundance; <0.1% of gut microbiota | Candida, Saccharomyces, Pichia, Aspergillus, Cladosporium | Immune modulation, SCFA interactions, cross-kingdom signalling | IBS, Crohn’s disease, leaky gut syndrome, inflammation | [111,114,119] |

| Viruses (Virome) | Highly individual-specific; thousands of contigs; bacteriophages dominate | crAssphage, Anelloviruses, Podoviridae, Siphoviridae | Bacterial population control, immune modulation, gene transfer | HIV-related immune suppression, IBD, early CRC markers | [34,128,130] |

| Archaea | Low diversity but stable presence; individual-specific | Methanobrevibacter, Methanosphaera, Methanomassiliicoccales | Methanogenesis, hydrogen scavenging, TMA reduction | IBD, metabolic disorders, possible cardiovascular effects | [122,143,149] |

| Protozoa and Helminths | Frequently excluded from gut microbiome datasets | Blastocystis (subtypes), others not often identified | Immune conditioning, microbial diversity regulation | Reduced vaccine efficacy, HIV/TB coinfection impact, context-dependent roles | [156,161,162] |

| Feature | Rural Populations | Urban Populations | Relevant Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial diversity | Higher alpha diversity reported in Bushbuckridge and Eastern Cape; Prevotella-rich profiles retained in less industrialised areas (e.g., Ghana, rural SA); diversity linked to traditional dietary practices | Lower microbial diversity observed in Soweto, Khayelitsha, and US cohorts; reduced beta diversity associated with lead/mercury exposure; microbial loss correlated with Westernised diets | [34,39,130,214,223] |

| Dominant fibre-degrading or VANISH taxa | Enriched Prevotella, Treponema, Succinatimonas, Succinivibrio, Vampirovibrio, Phascolarctobacterium, and Cryptobacteroides; associated with high-fibre, plant-based diets | Lower abundance or loss of these taxa; urban diets marked by higher energy, fat, and animal protein intake (e.g., ~3578 kcal/day in Khayelitsha) contributed to depletion of Prevotella and Treponema | [34,36,39,130] |

| Western-associated or pro-inflammatory taxa | Largely absent or less prevalent; lower abundance of bile-tolerant and inflammation-linked genera | Enrichment of Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Barnesiella, Alistipes, Bilophila, Lachnoclostridium, Haemophilus, crAssphage; associated with CRC and metabolic risk | [34,36,39,130,214,223] |

| Dietary patterns | Traditional, plant-based diets rich in fibre; low antibiotic use (e.g., Treponema succinifaciens persistence); lower energy intake (~2185 kcal/day); protective metabolic profile | Energy-dense diets with higher fat and animal protein intake in urban areas (e.g., Khayelitsha); associated with pro-inflammatory shifts in microbiota and bile acid metabolism | [34,36] |

| Metabolic/inflammatory risk markers | Lower levels of CRC- and T2DM-associated taxa; microbiota associated with favourable metabolic outcomes; higher Prevotella in Bushbuckridge linked to low-grade inflammation but unclear risk | Higher BMI, T2DM risk, and faecal deoxycholic acid (a CRC-associated metabolite) in urban individuals; toxicant exposure (lead, mercury) linked to shifts in pro-inflammatory taxa and metabolic stress | [34,39,214,223] |

| Inflammation and gut barrier integrity | No evidence of compromised gut barrier; overall diversity may confer protection | Soweto samples had elevated human DNA in stool, suggesting epithelial cell turnover, barrier disruption, or low-grade inflammation; HIV-associated microbiome showed reduced diversity | [36,130] |

| Environmental exposures | Less exposure was mentioned in rural settings | Urban samples (South Africa, USA) showed higher lead and mercury levels; associated with lower diversity and enrichment of Clostridium, Peptostreptococcales, and Ruminococcus | [214,223] |

| HIV statuses/associations | No rural cohorts were reported to have individuals living with HIV; Oduaran et al. (2020) [39] and Tamburini et al. (2022) [130] used individuals who tested negative for HIV; Maghini et al. (2025) [36] noted HIV-associated taxa in some rural samples (Dysosmobacter welbionis) | HIV-associated microbial signature (Dysosmobacter welbionis, Enterocloster spp.) with reduced diversity reported in urban Soweto; only Maghini et al. (2025) [36] included PLWH in their sample | [36,39,130] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mntambo, N.; Arumugam, T.; Pramchand, A.; Pillay, K.; Ramsuran, V. A Review of Global Patterns in Gut Microbiota Composition, Health and Disease: Locating South Africa in the Conversation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2831. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122831

Mntambo N, Arumugam T, Pramchand A, Pillay K, Ramsuran V. A Review of Global Patterns in Gut Microbiota Composition, Health and Disease: Locating South Africa in the Conversation. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2831. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122831

Chicago/Turabian StyleMntambo, Nombulelo, Thilona Arumugam, Ashiq Pramchand, Kamlen Pillay, and Veron Ramsuran. 2025. "A Review of Global Patterns in Gut Microbiota Composition, Health and Disease: Locating South Africa in the Conversation" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2831. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122831

APA StyleMntambo, N., Arumugam, T., Pramchand, A., Pillay, K., & Ramsuran, V. (2025). A Review of Global Patterns in Gut Microbiota Composition, Health and Disease: Locating South Africa in the Conversation. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2831. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122831