Inhibition of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Growth Through Nutrient Competition by Non-O157 E. coli Isolated from Cattle

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Collection

2.2. Bacterial Strain Isolation and Maintenance

2.3. Whole Genome Sequencing and Assembly

2.4. Genomic Analysis

2.5. Assessment of Anti-O157 Bacteriocin Production by Cattle Strains

2.6. Utilization of Select Carbon and Nitrogen Sources Under Anaerobic Conditions

2.7. Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS)

2.8. In Vitro Competition Assays of Cattle E. coli Isolate Consortia and O157

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Unique Commensal E. coli Isolates

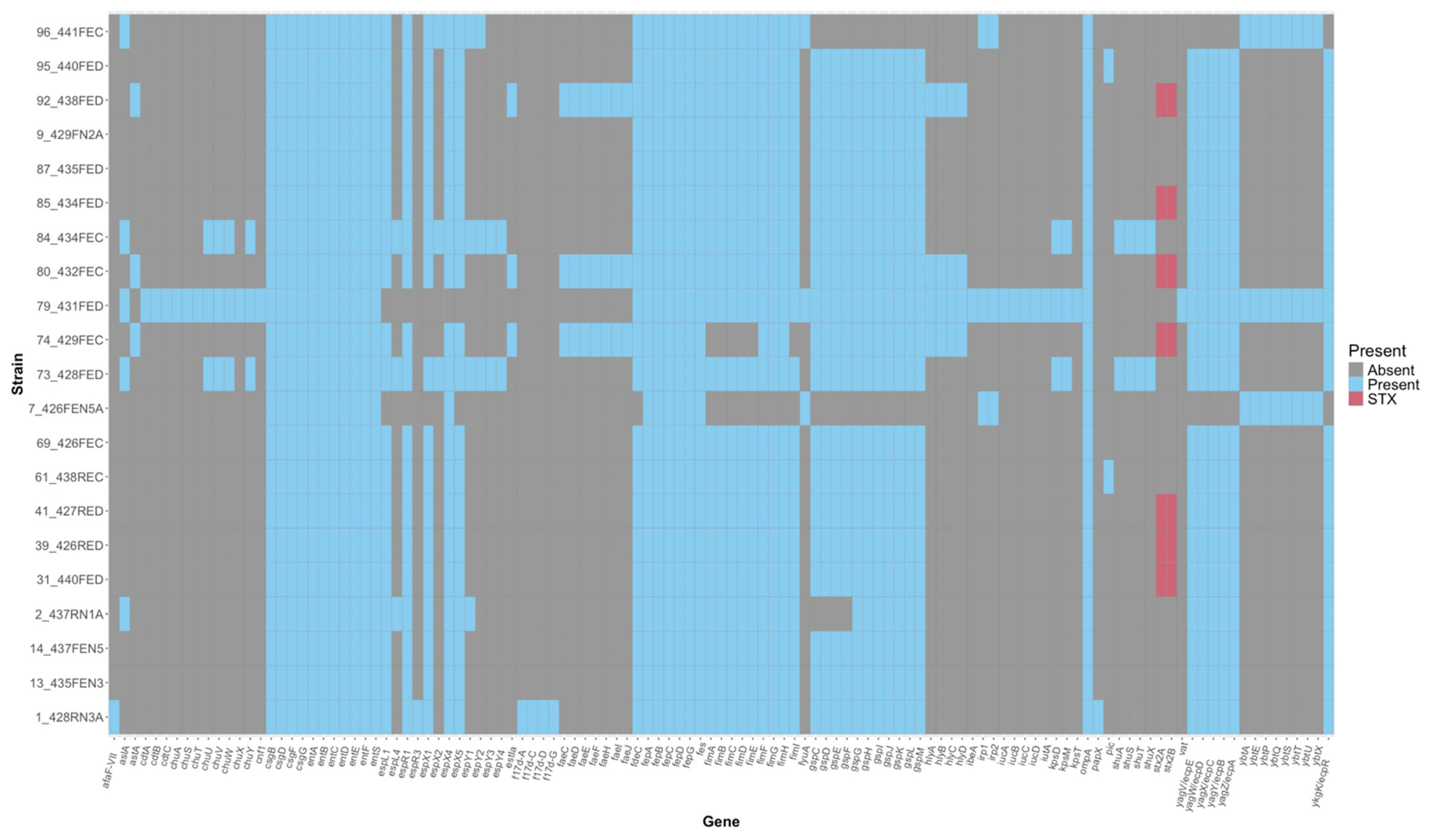

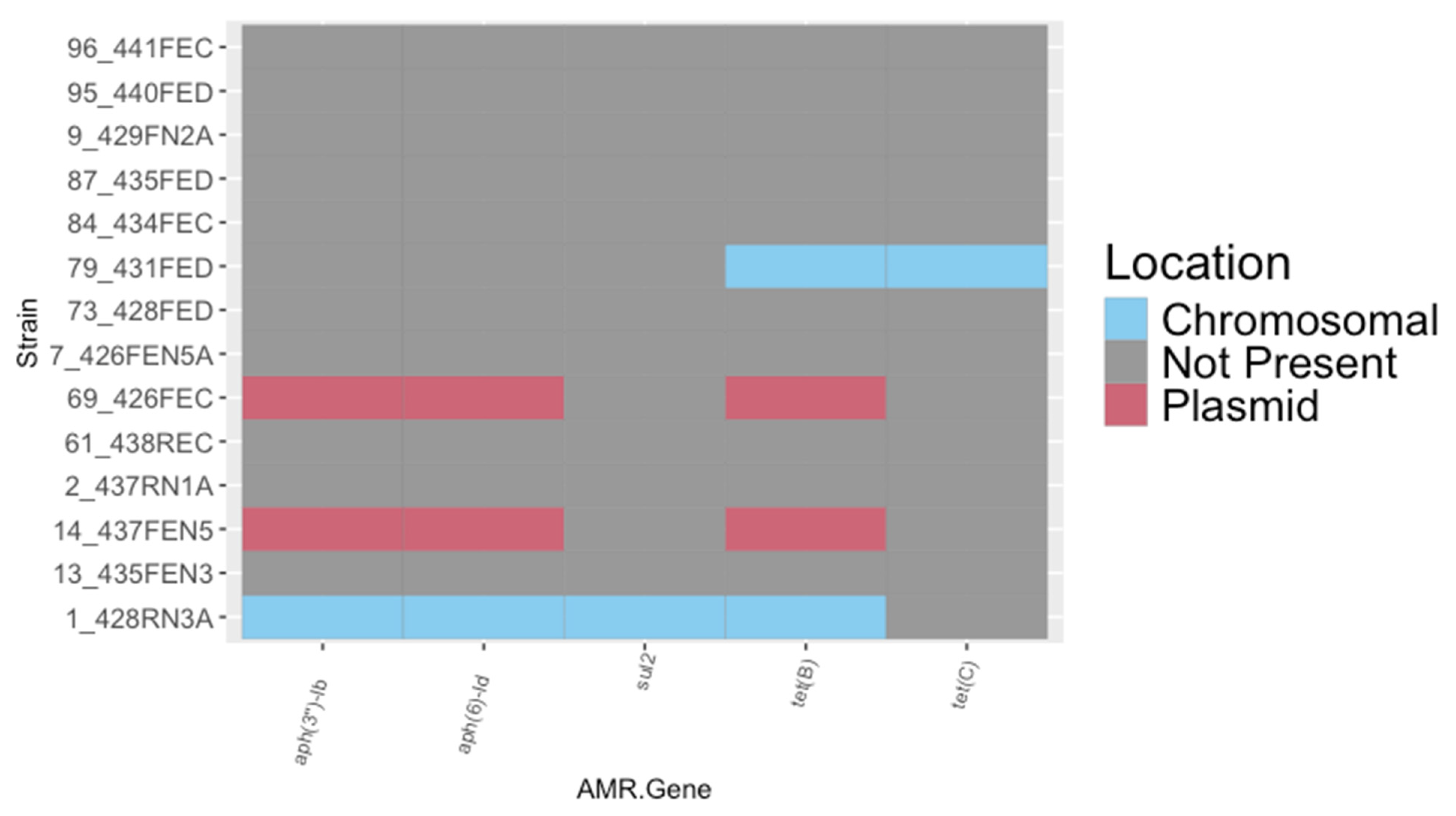

3.2. Genomic Analysis of Unique Non-O157 E. coli Strains

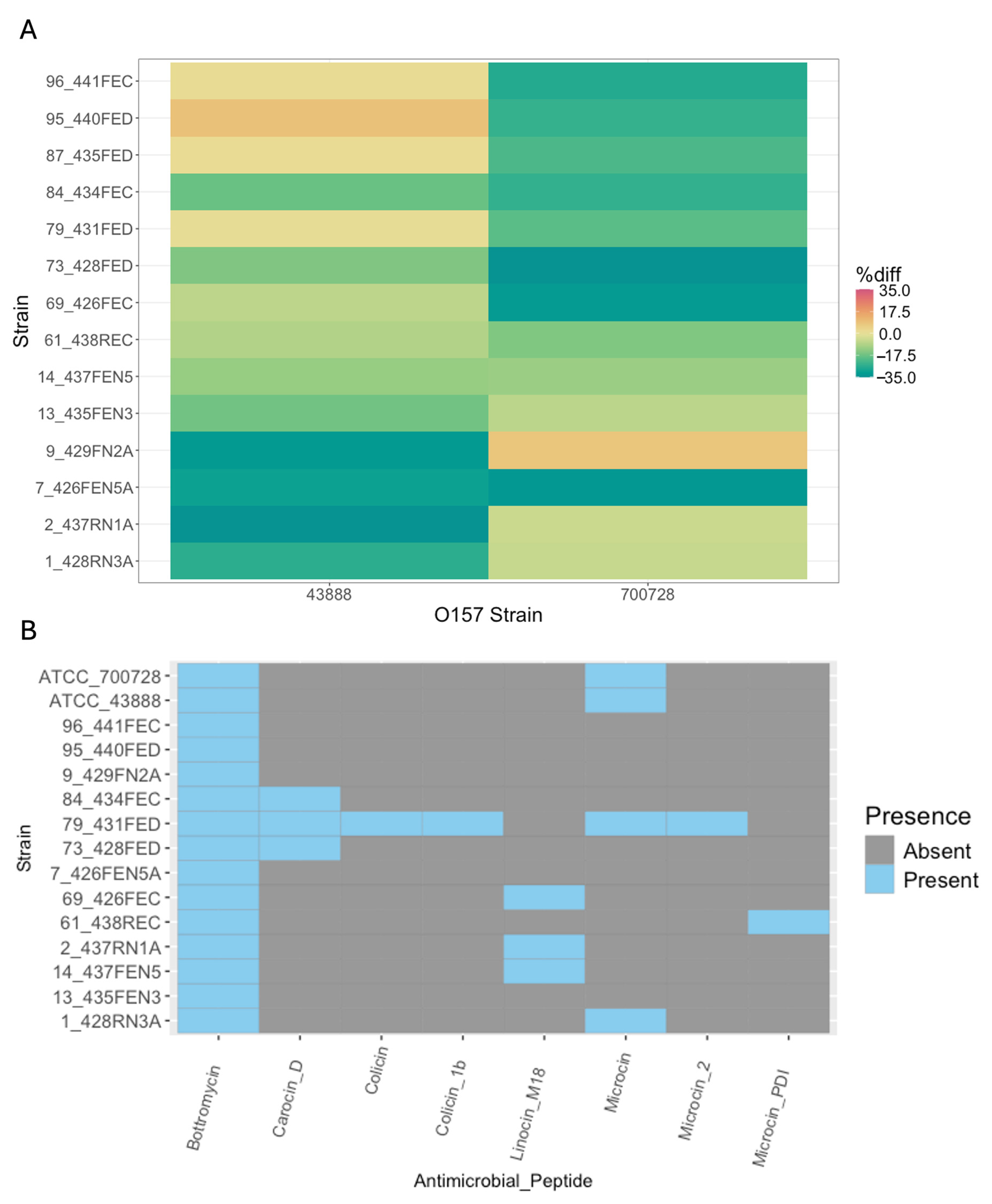

3.3. Phenotypic and Genotypic Assessment of Bacteriocin Production Against O157

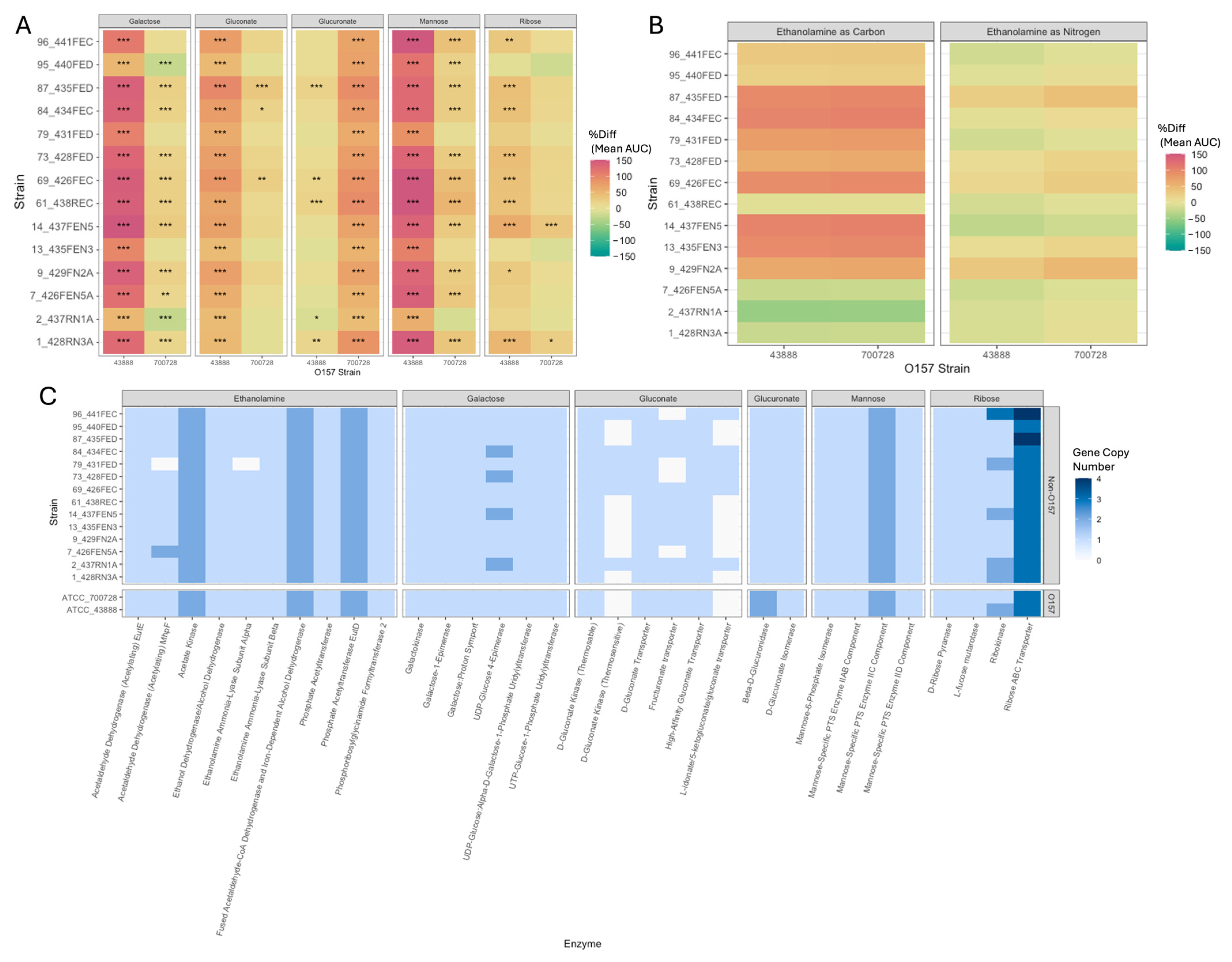

3.4. Phenotypic and Genotypic Nutrient Utilization of O157

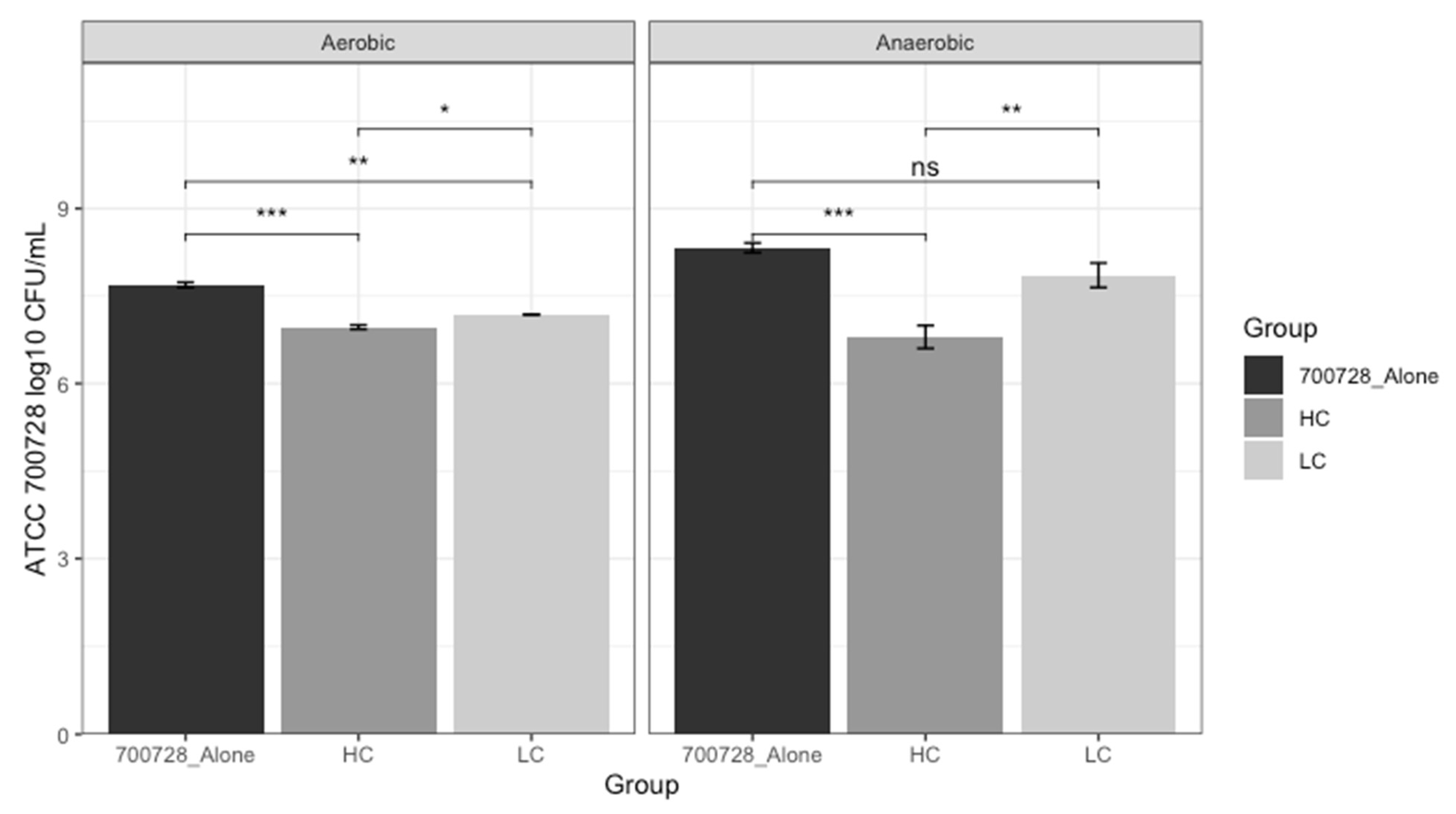

3.5. Consortia of High and Low Competitor Strains vs. E. coli O157

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majowicz, S.E.; Scallan, E.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Sargeant, J.M.; Stapleton, J.; Angulo, F.J.; Yeung, D.H.; Kirk, M.D. Global incidence of human Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli infections and deaths: A systematic review and knowledge synthesis. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2014, 11, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, S.; White, A.E.; McQueen, R.B.; Ahn, J.-W.; Gunn-Sandell, L.B.; Scallan Walter, E.J. Economic burden of foodborne illnesses acquired in the United States. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2024, 22, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel, J.M.; Sparling, P.H.; Crowe, C.; Griffin, P.M.; Swerdlow, D.L. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157: H7 outbreaks, United States, 1982–2002. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.J.; Ryu, S.J.; Chae, J.S.; Eo, S.K.; Woo, G.J.; Lee, J.H. Occurrence and characteristics of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 in calves associated with diarrhoea. Vet. Microbiol. 2004, 98, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejek, A.M.; Minnich, S.A.; Hovde, C.J. Escherichia coli 0157:H7 virulence factors and the ruminant reservoir. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 35, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, T.M.; Bosilevac, J.M.; Nou, X.; Shackelford, S.D.; Wheeler, T.L.; Kent, M.P.; Jaroni, D.; Pauling, B.; Allen, D.M.; Koohmaraie, M. Escherichia coli O157 prevalence and enumeration of aerobic bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, and Escherichia coli O157 at various steps in commercial beef processing plants. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puligundla, P.; Lim, S. Biocontrol approaches against Escherichia coli O157:H7 in foods. Foods 2022, 11, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, R.; Vakkalanka, M.S.; Onumpai, C.; Chau, H.K.; White, A.; Rastall, R.A.; Yam, K.; Hotchkiss, A.T. Pectic oligosaccharide structure-function relationships: Prebiotics, inhibitors of Escherichia coli O157:H7 adhesion and reduction of Shiga toxin cytotoxicity in HT29 cells. Food Chem. 2017, 227, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, K.; Marongiu, L.; Detert, K.; Venturelli, S.; Schmidt, H.; Hoelzle, L.E. Phage applications for biocontrol of enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 439, 111267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.T.; Drouillard, J.S.; Nagaraja, T.G. Competitive exclusion Escherichia coli cultures on E. coli O157 growth in batch culture ruminal or fecal microbial fermentation. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2008, 6, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J. Biological control of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in dairy manure-based compost using competitive exclusion microorganisms. Pathogens 2024, 13, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyte, K.Z.; Rakoff-Nahoum, S. Understanding competition and cooperation within the mammalian gut microbiome. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R538–R544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.N.; Barua, N.; Tin, M.C.F.; Dharmaratne, P.; Wong, S.H.; Ip, M. The use of probiotics and prebiotics in decolonizing pathogenic bacteria from the gut; a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2356279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leatham Mary, P.; Banerjee, S.; Autieri Steven, M.; Mercado-Lubo, R.; Conway, T.; Cohen Paul, S. Precolonized human commensal Escherichia coli strains serve as a barrier to E. coli O157:H7 growth in the streptomycin-treated mouse intestine. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 2876–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.; Silva, V.; Dapkevicius, M.D.; Caniça, M.; Tejedor-Junco, M.T.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Escherichia coli as commensal and pathogenic bacteria among food-producing animals: Health implications of extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production. Animals 2020, 10, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurtsen, J.; de Been, M.; Weerdenburg, E.; Zomer, A.; McNally, A.; Poolman, J. Genomics and pathotypes of the many faces of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 46, fuac031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano-Vazquez, U.; Verstraeten, S.; Martin, R.; Chain, F.; Langella, P.; Thomas, M.; Cherbuy, C. The commensal Escherichia coli CEC15 reinforces intestinal defences in gnotobiotic mice and is protective in a chronic colitis mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spragge, F.; Bakkeren, E.; Jahn, M.T.; Araujo, E.B.N.; Pearson, C.F.; Wang, X.; Pankhurst, L.; Cunrath, O.; Foster, K.R. Microbiome diversity protects against pathogens by nutrient blocking. Science 2023, 382, eadj3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.S.; Silva, A.A.; Vieira, A.T.; Barbosa, F.H.F.; Arantes, R.M.E.; Teixeira, M.M.; Nicoli, J.R. Comparative study of Bifidobacterium animalis, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus casei and Saccharomyces boulardii probiotic properties. Arch. Microbiol. 2009, 191, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar, T.M. Insights from 100 years of research with probiotic E. coli. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 6, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenborn, U.; Schulze, J. The non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917—Features of a versatile probiotic. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2009, 21, 122–158. [Google Scholar]

- Fábrega, M.-J.; Rodríguez-Nogales, A.; Garrido-Mesa, J.; Algieri, F.; Badía, J.; Giménez, R.; Gálvez, J.; Baldomá, L. Intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of outer membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in DSS-experimental colitis in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1274. [Google Scholar]

- Fabich Andrew, J.; Jones Shari, A.; Chowdhury Fatema, Z.; Cernosek, A.; Anderson, A.; Smalley, D.; McHargue, J.W.; Hightower, G.A.; Smith, J.T.; Autieri, S.M.; et al. Comparison of carbon nutrition for pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli strains in the mouse intestine. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Bouguénec, C.; Schouler, C. Sugar metabolism, an additional virulence factor in enterobacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 301, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, Y.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Robbe-Masselot, C.; Durand, A.; de la Foye, A.; Harel, J.; Cohen, P.S.; Conway, T.; Forano, E.; Martin, C. Carbohydrate utilization by enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in bovine intestinal content. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, R.; Leatham-Jensen, M.P.; Gibson, T.; Cohen, P.S.; Conway, T. Nutritional Basis for Colonization resistance by human commensal Escherichia coli strains HS and Nissle 1917 against E. coli O157:H7 in the mouse intestine. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall Melissa, M.; Gruber Charley, C.; Parker Christopher, T.; Sperandio, V. Ethanolamine controls expression of genes encoding components involved in interkingdom signaling and virulence in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. mBio 2012, 3, e00050-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, T.; Cohen Paul, S. Commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli metabolism in the gut. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-W.; Won, H.-S. Advancements in the application of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs). Biomolecules 2024, 14, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budič, M.; Rijavec, M.; Petkovšek, Ž.; Žgur-Bertok, D. Escherichia coli bacteriocins: Antimicrobial efficacy and prevalence among isolates from patients with bacteraemia. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, I.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. Bacteriocin diversity, function, discovery and application as antimicrobials. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradisteanu Pircalabioru, G.; Popa, L.I.; Marutescu, L.; Gheorghe, I.; Popa, M.; Czobor Barbu, I.; Cristescu, R.; Chifiriuc, M. Bacteriocins in the era of antibiotic resistance: Rising to the challenge. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schamberger, G.P.; Diez-Gonzalez, F. Assessment of resistance to colicinogenic Escherichia coli by E. coli O157:H7 strains. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askari, N.; Ghanbarpour, R. Molecular investigation of the colicinogenic Escherichia coli strains that are capable of inhibiting E. coli O157:H7 in vitro. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peroutka-Bigus, N.; Nielsen Daniel, W.; Trachsel, J.; Mou Kathy, T.; Sharma Vijay, K.; Kudva Indira, T.; Loving, C.L. Phenotypic and genomic comparison of three human outbreak and one cattle-associated Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e04140-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, B. BBMap Short-Read Aligner, and Other Bioinformatics Tools; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, G.; Abueg, L.; Brajuka, A.; Brajuka, N.; Gallardo-Alba, C.; Giani, A.; Fedrigo, O.; Jarvis, E.D. Gfastats: Conversion, evaluation and manipulation of genome sequences using assembly graphs. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 4214–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardine, B.; Riemer, C.; Hardison, R.C.; Burhans, R.; Elnitski, L.; Shah, P.; Shah, P.; Zhang, Y.; Blankenberg, D.; Albert, I.; et al. Galaxy: A platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res. 2005, 15, 1451–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.; Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Phillippy, A.M.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Aluru, S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.L.M.; Conrad Roth, E.; Viver, T.; Feistel Dorian, J.; Lindner Blake, G.; Venter Stephanus, N.; Orellana, L.H.; Amann, R.; Rossello-Mora, R.; Konstantinidis, K.T. An ANI gap within bacterial species that advances the definitions of intra-species units. mBio 2023, 15, e02696-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.G.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, A.J.; Taylor, B.; Delaney, A.J.; Soares, J.; Seemann, T.; Keane, J.A.; Harris, S.R. SNP-sites: Rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharat, A.; Petkau, A.; Avery, B.P.; Chen, J.C.; Folster, J.P.; Carson, C.A.; Kearney, A.; Nadon, C.; Mabon, P.; Thiessen, J.; et al. Correlation between phenotypic and in silico detection of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella enterica in Canada using Staramr. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Nash, J.H.E. MOB-suite: Software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessonov, K.; Laing, C.; Robertson, J.; Yong, I.; Ziebell, K.; Gannon, V.P.J.; Nichani, A.; Arya, G.; Nash, J.H.E.; Christianson, S. ECTyper: In silico Escherichia coli serotype and species prediction from raw and assembled whole-genome sequence data. Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, J.; Yu, J.; Yao, Z.; Sun, L.; Shen, Y.; Jin, Q. VFDB: A reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33 (Suppl. 1), D325–D328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heel, A.J.; de Jong, A.; Song, C.; Viel, J.H.; Kok, J.; Kuipers, O.P. BAGEL4: A user-friendly web server to thoroughly mine RiPPs and bacteriocins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W278–W281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medema, M.H.; Blin, K.; Cimermancic, P.; de Jager, V.; Zakrzewski, P.; Fischbach, M.A.; Weber, T.; Takano, E.; Breitling, R. antiSMASH: Rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (Suppl. 2), W339–W346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, M.; Borton, M.A.; Bolduc, B.; Faria, J.P.; Flynn, R.M.; Ghadermazi, P.; Edirisinghe, J.N.; Wood-Carlson, E.M.; Miller, C.S.; Chan, S.H.J.; et al. kb_DRAM: Annotation and metabolic profiling of genomes with DRAM in KBase. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad110, Erratum in Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Uematsu, M.; Fujimoto, K.; Uematsu, S.; Imoto, S. ggkegg: Analysis and visualization of KEGG data utilizing the grammar of graphics. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twomey, E.; Hill, C.; Field, D.; Begley, M. Recipe for success: Suggestions and recommendations for the isolation and characterisation of bacteriocins. Int. J. Microbiol. 2021, 2021, 9990635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglin, R.C.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Meile, L.; Lacroix, C.; Meile, L. High-throughput screening assays for antibacterial and antifungal activities of Lactobacillus species. J. Microbiol. Methods 2015, 114, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, R.M.; Cowan, D.A.; Morgan, H.W.; Curran, M.P. A correlation between protein thermostability and resistance to proteolysis. Biochem. J. 1982, 207, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, F.; Lanza, V.F.; Baquero, M.-R.; del Campo, R.; Bravo-Vázquez, D.A. Microcins in Enterobacteriaceae: Peptide antimicrobials in the eco-active intestinal chemosphere. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprouffske, K.; Wagner, A. Growthcurver: An R package for obtaining interpretable metrics from microbial growth curves. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira de Gouveia, M.I.; Daniel, J.; Garrivier, A.; Bernalier-Donadille, A.; Jubelin, G. Diversity of ethanolamine utilization by human commensal Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 2023, 174, 103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynildsrud, O.; Bohlin, J.; Scheffer, L.; Eldholm, V. Rapid scoring of genes in microbial pan-genome-wide association studies with Scoary. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 238, Erratum in Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, H.G.; Seidel, D.S.; Callaway, T.R. Preharvest animal management controls and intervention options for reducing Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli shedding in cattle: A critical analysis. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2025; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Daliri, E.B.-M.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Ding, T. Inhibitory Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria on Foodborne Pathogens: A Review. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, W.J.; Kang, S.-S. Inhibitory effect of bacteriocin-producing Lactobacillus brevis DF01 and Pediococcus acidilactici K10 isolated from kimchi on enteropathogenic bacterial adhesion. Food Biosci. 2019, 30, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapountzis, P.; Segura, A.; Desvaux, M.; Forano, E. An Overview of the Elusive Passenger in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Cattle: The Shiga Toxin Producing Escherichia coli. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehus, R.; Oliveira, N.M.; Li, A.; Fletcher, A.G.; Foster, K.R. The evolution of strategy in bacterial warfare via the regulation of bacteriocins and antibiotics. eLife 2021, 10, e69756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyles, C.L. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: An overview. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85 (Suppl. 13), E45–E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.T.; Sowers, E.G.; Wells, J.G.; Greene, K.D.; Griffin, P.M.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Strockbine, N.A. Non-O157 Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States, 1983–2002. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puorger, C.; Vetsch, M.; Wider, G.; Glockshuber, R. Structure, folding and stability of FimA, the main structural subunit of type 1 pili from uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 412, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štaudová, B.; Micenková, L.; Bosák, J.; Hrazdilová, K.; Slaninková, E.; Vrba, M.; Ševciková, A.; Kohoutová, D.; Woznicová, V.; Bures, J.; et al. Determinants encoding fimbriae type 1 in fecal Escherichia coli are associated with increased frequency of bacteriocinogeny. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, P. The fimA gene encoding the type-1 fimbrial subunit of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984, 143, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiela Dagmara, I.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Tchesnokova, V.; Paul, S.; Weissman Scott, J.; Medenica, I.; Clegg, S.; Sokurenko, E.V. Evolutionary analysis points to divergent physiological roles of type 1 fimbriae in Salmonella and Escherichia coli. mBio 2013, 4, e00625-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Schumann, M.; Schneemann, M.; Dony, V.; Fromm, A.; Nagel, O.; Schulzke, J.; Bucker, R. Escherichia coli alpha-hemolysin HlyA induces host cell polarity changes, epithelial barrier dysfunction and cell detachment in human colon carcinoma Caco-2 cell model via PTEN-dependent dysregulation of cell junctions. Toxins 2021, 13, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakbin, B.; Brück, W.M.; Rossen, J.W.A. Virulence factors of enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Beltrán, J.; DelaFuente, J.; León-Sampedro, R.; MacLean, R.C.; San Millán, Á. Beyond horizontal gene transfer: The role of plasmids in bacterial evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda-Barba, S.; Top, E.M.; Stalder, T. Plasmids, a molecular cornerstone of antimicrobial resistance in the One Health era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, A.; Alhanout, K.; Duval, R.E. Bacteriocins, antimicrobial peptides from bacterial origin: Overview of their biology and their impact against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.H.; Truman, A.W. Genome mining strategies for ribosomally synthesised and post-translationally modified peptides. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1838–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Cantos, M.V.; Garcia-Morena, D.; Yi, Y.; Liang, L.; Gómez-Vázquez, E.; Kuipers, O.P. Bioinformatic mining for RiPP biosynthetic gene clusters in Bacteroidales reveals possible new subfamily architectures and novel natural products. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1219272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, T.R.; Stahl, C.H.; Edrington, T.S.; Genovese, K.J.; Lincoln, L.M.; Anderson, R.C.; Lonergan, S.M.; Poole, T.L.; Harvey, R.B.; Nisbet, D.J. Colicin concentrations inhibit growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in vitro. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 2603–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo, P.O.d.S.; Converti, A.; Gierus, M.; Oliveira, R.P.d.S. Antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance produced by Pediococcus pentosaceus: From shake flasks to bioreactor. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M.A.; Wertz, J.E. Bacteriocin diversity: Ecological and evolutionary perspectives. Biochimie 2002, 84, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.M.; O’Brien, C.L. Bacteriocin diversity and the frequency of multiple bacteriocin production in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 2006, 152, 3239–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durso Lisa, M.; Smith, D.; Hutkins Robert, W. Measurements of fitness and competition in commensal Escherichia coli and E. coli O157:H7 strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 6466–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, A.; Zaheer, R.; Adator, E.H.; Barbieri, R.; Reuter, T.; McAllister, T.A. Bacteriocin occurrence and activity in Escherichia coli isolated from bovines and wastewater. Toxins 2019, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsova, M.V.; Mihailovskaya, V.S.; Remezovskaya, N.B.; Starčič Erjavec, M. Bacteriocin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of farm animals: Prevalence, molecular characterization and potential for application. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.; O’Connor, P.M.; Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Field, D.; Begley, M. Identification and characterisation of capidermicin, a novel bacteriocin produced by Staphylococcus capitis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimipour, A.K.; Gross, T. Mapping the bacterial metabolic niche space. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ibrahim, M.; Cui, Z.; Xie, G.; Jin, G.; Kube, M.; Li, B.; Zhou, X. Multi-omics analysis of niche specificity provides new insights into ecological adaptation in bacteria. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2072–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.; Ferrández, A.; Prieto María, A.; García José, L. Biodegradation of aromatic compounds by Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001, 65, 523–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Yoon, S.H. A single amino acid substitution in aromatic hydroxylase (HpaB) of Escherichia coli alters substrate specificity of the structural isomers of hydroxyphenylacetate. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wu, P.; Guo, A.; Yang, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhang, Q. Research progress on the regulation of production traits by gastrointestinal microbiota in dairy cows. Front. Veter. Sci. 2023, 10, 1206346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Lai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, W.; Mao, S. The gastrointestinal microbiome in dairy cattle is constrained by the deterministic driver of the region and the modified effect of diet. Microbiome 2023, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Breaker, J.D.; Suen, G. Microbial succession in the gastrointestinal tract of dairy cows from 2 weeks to first lactation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garsin, D.A. Ethanolamine utilization in bacterial pathogens: Roles and regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley Carol, A.; Anderson Christopher, J.; Kendall Melissa, M. Ethanolamine influences human commensal Escherichia coli growth, gene expression, and competition with enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7. mBio 2018, 9, e01429-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgo, M.; Mostowy, S.; Ho, B.T. Emerging models to study competitive interactions within bacterial communities. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangan, M.S.; Vasconcelos, M.M.; Mitra, U.; Câmara, O.; Boedicker, J.Q. Intertemporal trade-off between population growth rate and carrying capacity during public good production. iScience 2022, 25, 104117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osbelt, L.; Wende, M.; Almási, É.; Derksen, E.; Muthukumarasamy, U.; Lesker, T.R.; Galvez, E.J.C.; Pils, M.C.; Schalk, E.; Chhatwal, P.; et al. Klebsiella oxytoca causes colonization resistance against multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae in the gut via cooperative carbohydrate competition. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1663–1679.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uffelmann, E.; Huang, Q.Q.; Munung, N.S.; de Vries, J.; Okada, Y.; Martin, A.R.; Martin, H.C.; Lappalainen, T.; Posthuma, D. Genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperotti, A.; Brameyer, S.; Fabiani, F.; Jung, K. Phenotypic heterogeneity of microbial populations under nutrient limitation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Zoumpopoulou, G.; Foligné, B.; Alexandraki, V.; Kazou, M.; Pot, B.; Tsakalidou, E. Discovering probiotic microorganisms: In vitro, in vivo, genetic and omics approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinderola, G.; Gueimonde, M.; Gomez-Gallego, C.; Delfederico, L.; Salminen, S. Correlation between in vitro and in vivo assays in selection of probiotics from traditional species of bacteria. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, S.A.; Koudelka, G.B. Shiga toxin: Expression, distribution, and its role in the environment. Toxins 2011, 3, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelli, G.; Claudia, V.; Mastromarino, P. Phenotyping and genotyping are both essential to identify and classify a probiotic microorganism. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2013, 24, 20105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Maravilla, E.; Reyes-Pavón, D.; Benítez-Cabello, A.; González-Vázquez, R.; Ramírez-Chamorro, L.M.; Langella, P.; Bermudez-Humarán, L.G. Strategies for the identification and assessment of bacterial strains with specific probiotic traits. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, J.N.; Rea, M.C.; O’Connor, P.M.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. Human skin microbiota is a rich source of bacteriocin-producing Staphylococci that kill human pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiy241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Yan, J.; Kang, C.; Yang, B. Enterohaemorrhagic, E. coli utilizes host- and microbiota-derived L-malate as a signaling molecule for intestinal colonization. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-J.; Wang, S.-T.; Lin, C.-M.; Chiu, H.-C.; Huang, C.-R.; Lee, D.-Y.; Chang, G.-D.; Chou, T.-C.; Chen, J.-W. A multi-omic analysis reveals the role of fumarate in regulating the virulence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maki, J.J.; Mou, K.T.; Trachsel, J.; Loving, C.L. Inhibition of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Growth Through Nutrient Competition by Non-O157 E. coli Isolated from Cattle. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2811. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122811

Maki JJ, Mou KT, Trachsel J, Loving CL. Inhibition of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Growth Through Nutrient Competition by Non-O157 E. coli Isolated from Cattle. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2811. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122811

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaki, Joel J., Kathy T. Mou, Julian Trachsel, and Crystal L. Loving. 2025. "Inhibition of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Growth Through Nutrient Competition by Non-O157 E. coli Isolated from Cattle" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2811. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122811

APA StyleMaki, J. J., Mou, K. T., Trachsel, J., & Loving, C. L. (2025). Inhibition of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Growth Through Nutrient Competition by Non-O157 E. coli Isolated from Cattle. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2811. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122811