Differential Assembly of Rhizosphere Microbiome and Metabolome in Rice with Contrasting Resistance to Blast Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

2.2. Soil Collection and Physicochemical Analysis

2.3. Analysis of Rhizosphere Soil Microorganisms

2.4. Analysis of Root Metabolites

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Soil Physicochemical Properties

3.2. Changes in Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Communities

3.2.1. Sequencing Data Analysis

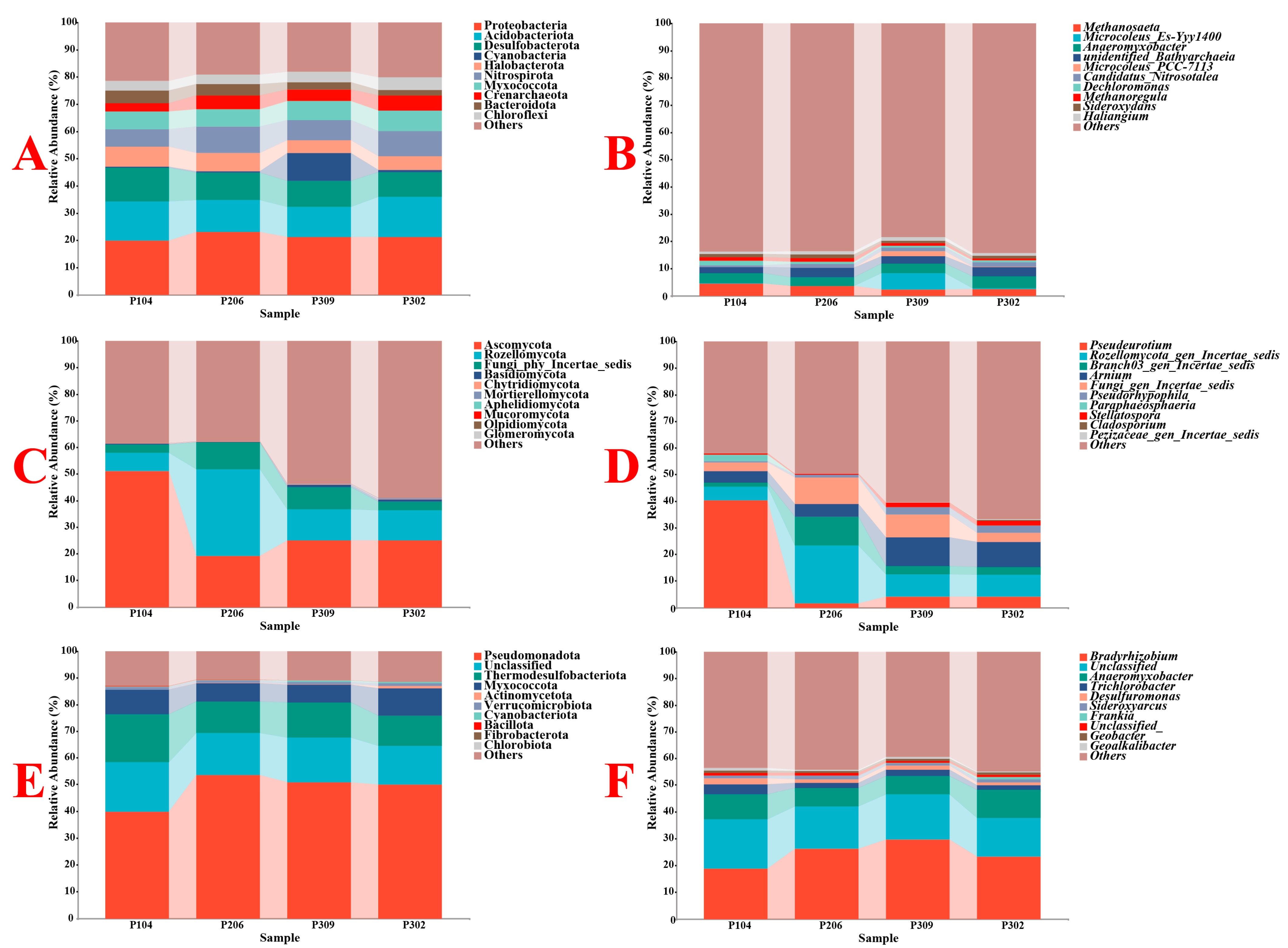

3.2.2. Microbial Composition and Abundance

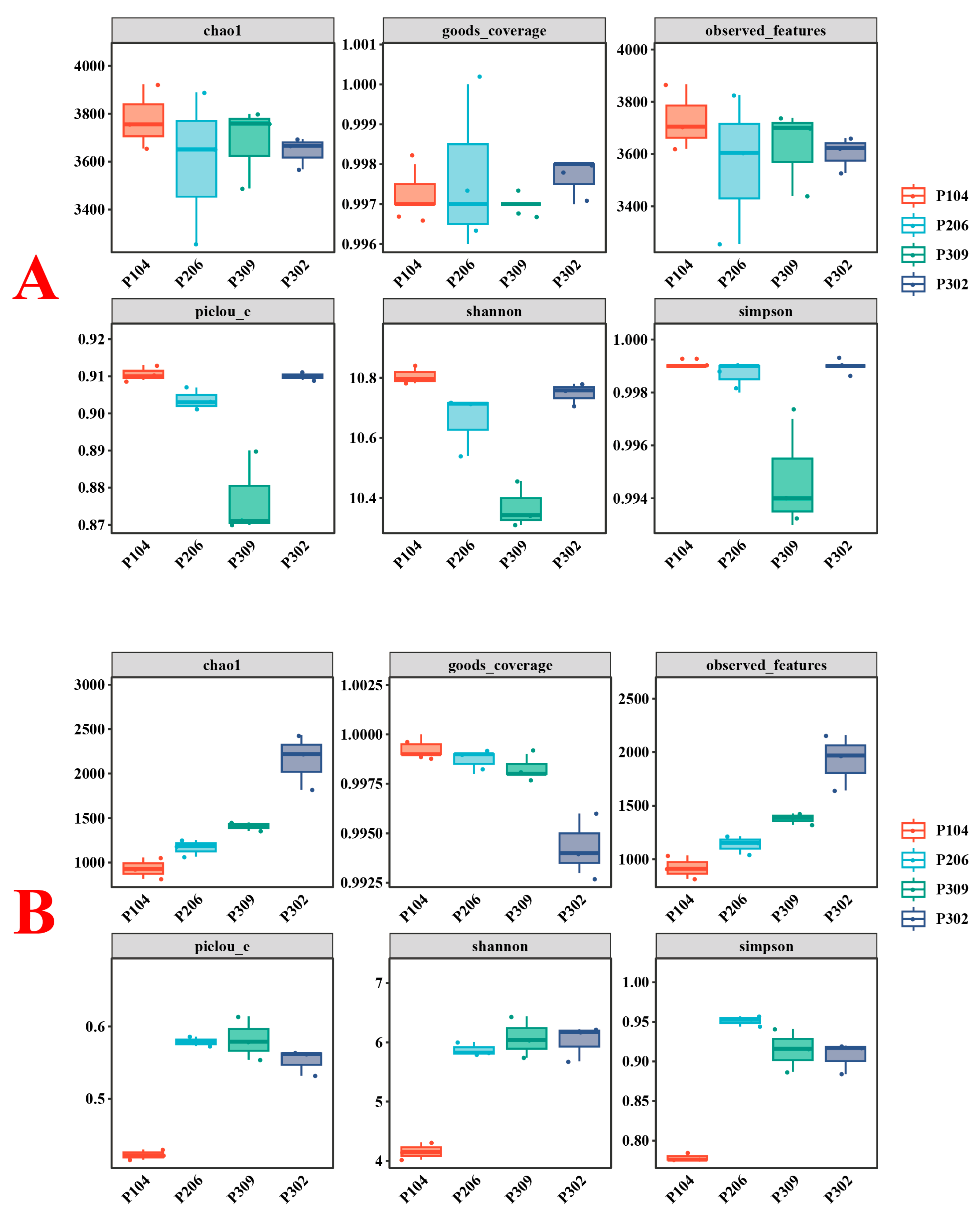

3.2.3. Alpha Diversity of Microbial Communities

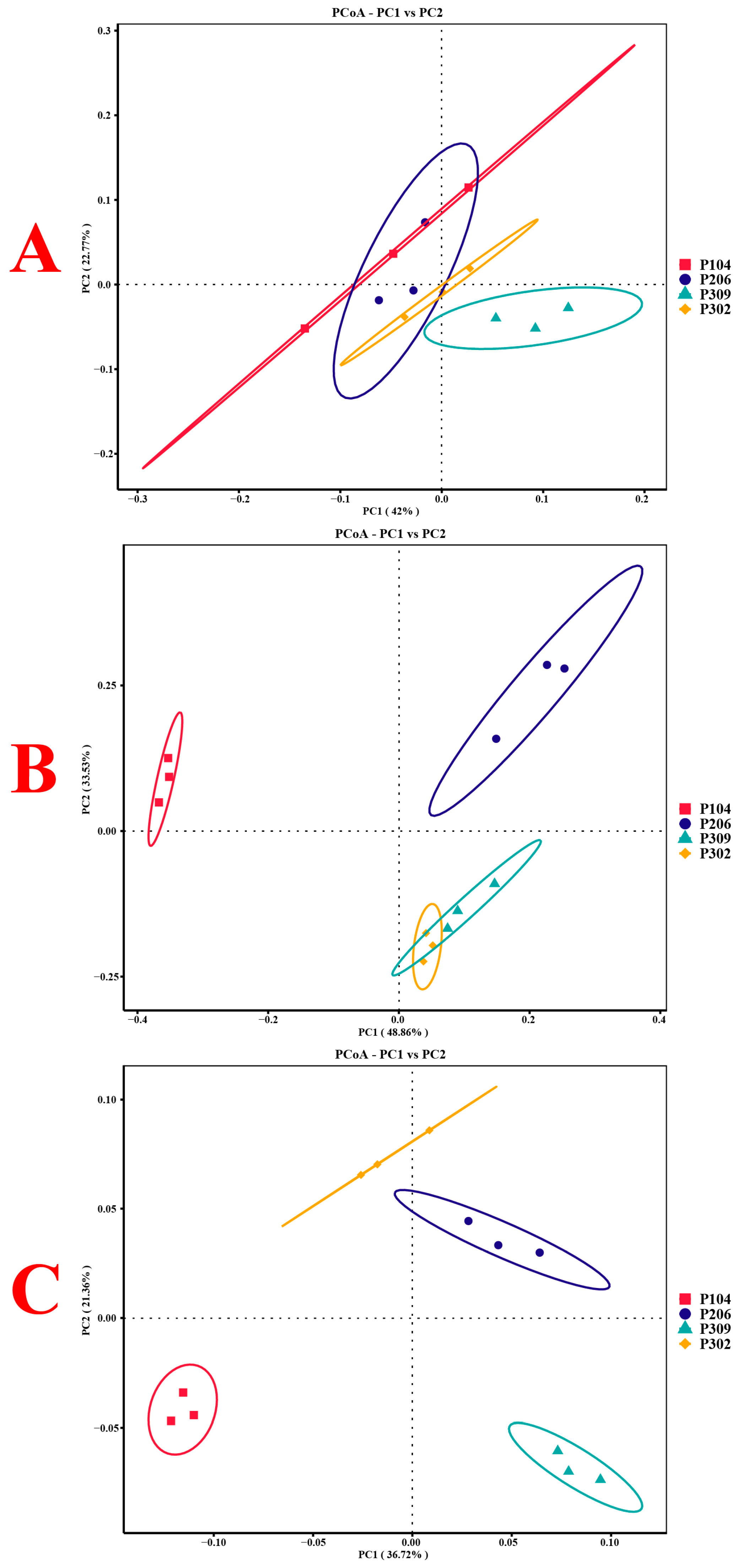

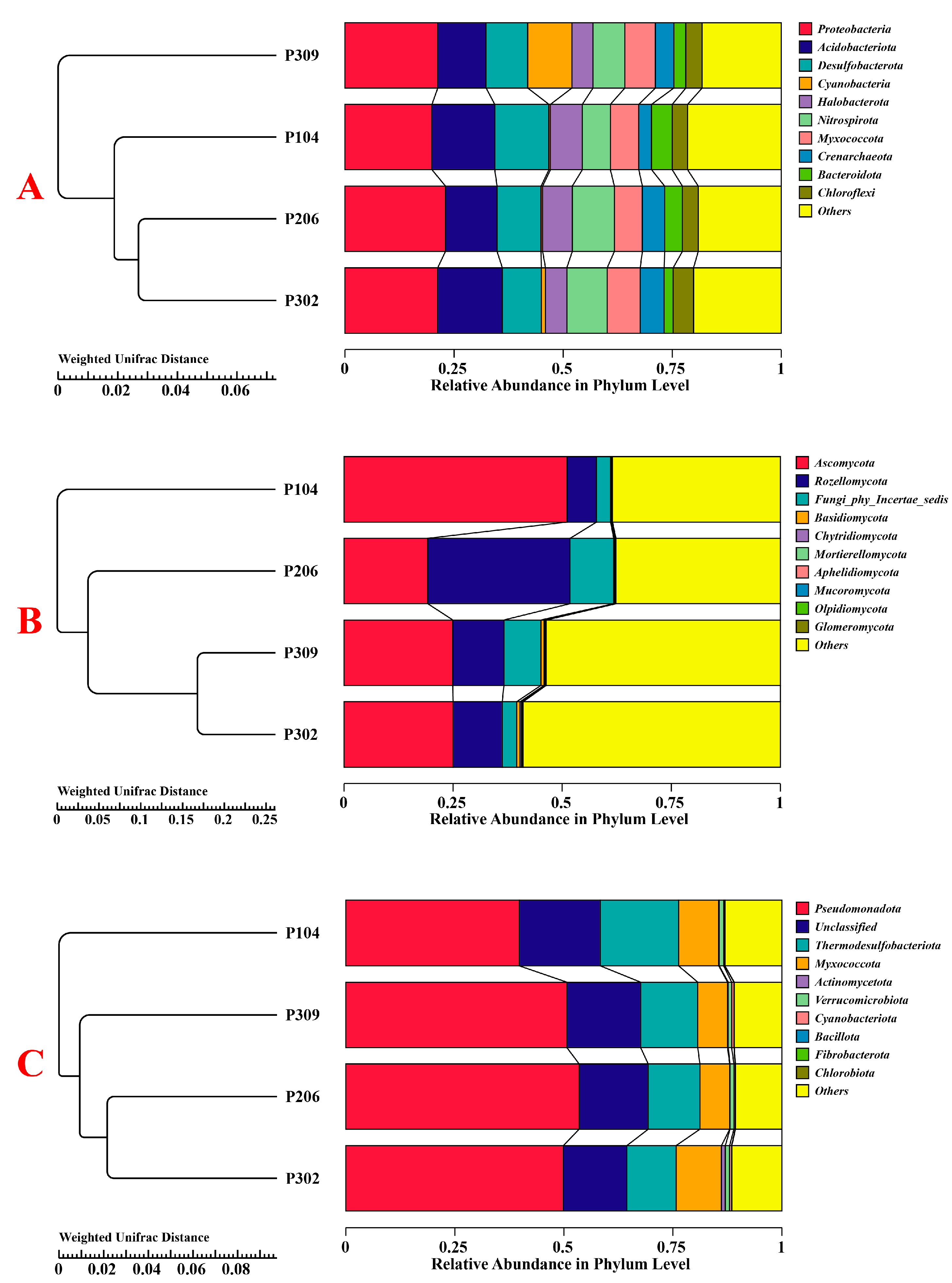

3.2.4. Structural Changes in Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Communities

3.2.5. Functional Changes in Rhizosphere Soil Microorganisms

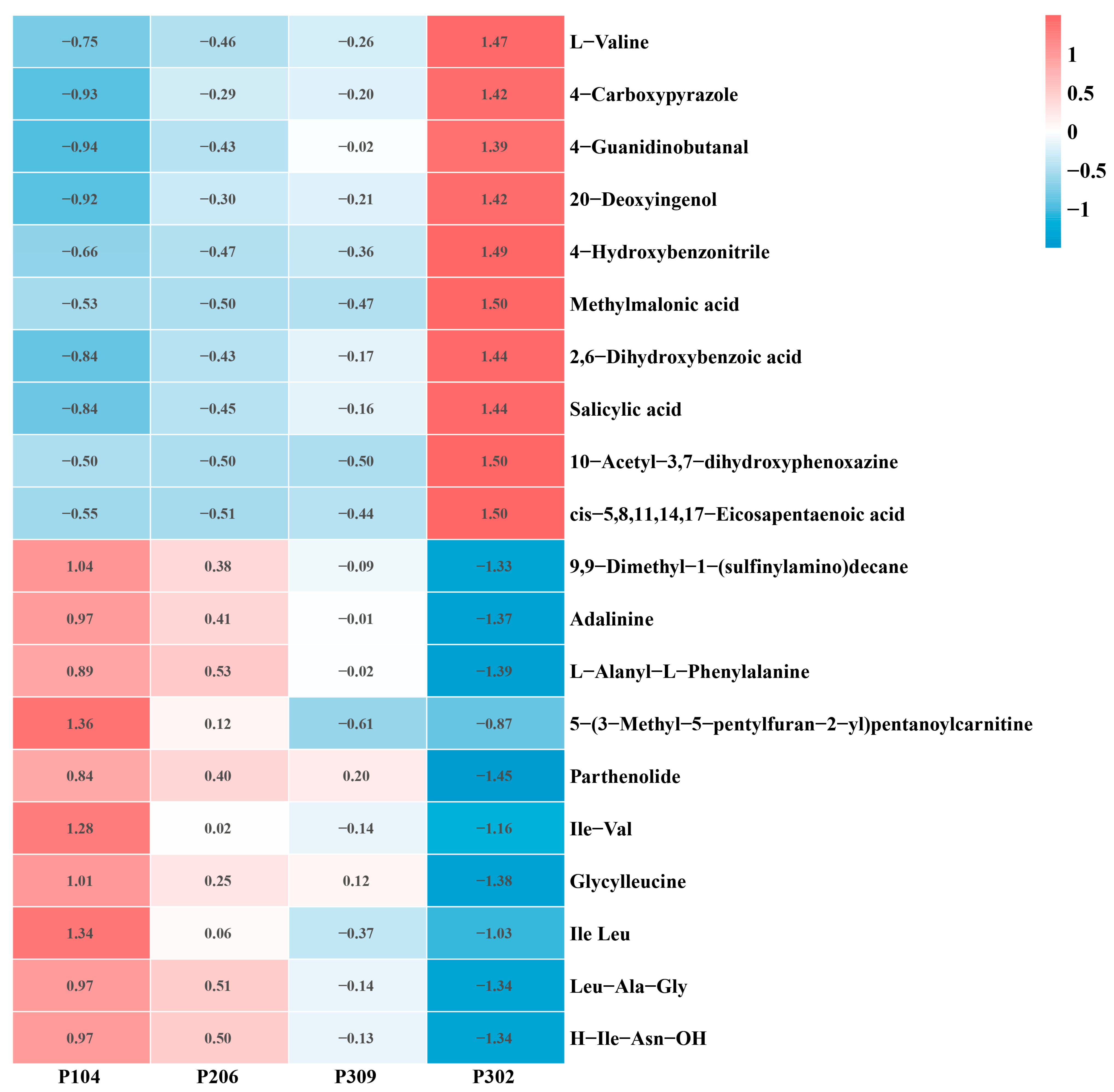

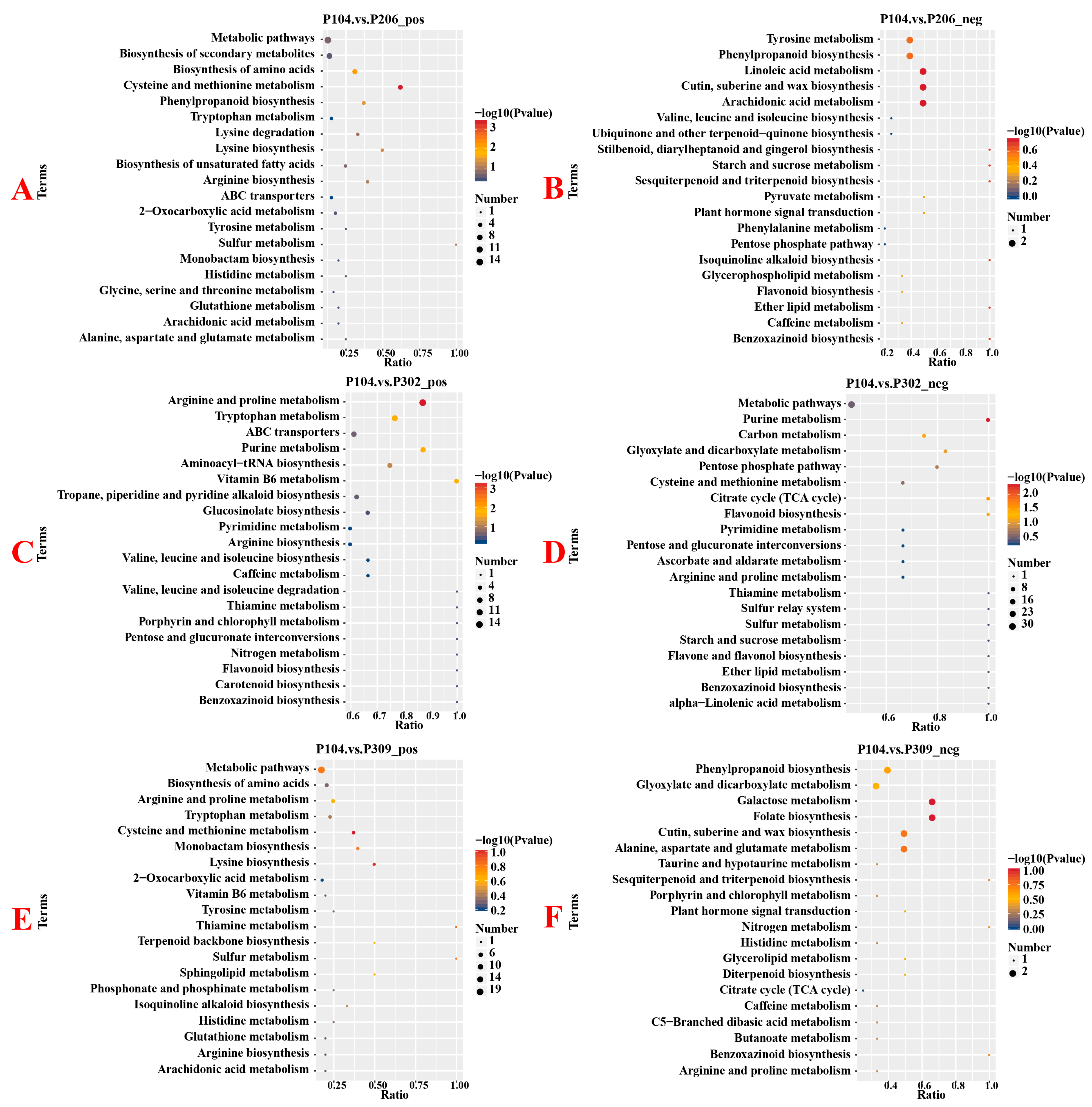

3.3. Differences in Root Metabolites

3.4. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, L.; Shao, Z.; Fu, Y.; Li, Z.; Ni, G.; Cheng, X.; Wen, Y.; Wei, S. iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of rice seedlings’ resistance induced by Streptomyces JD211 against Magnaporthe oryzae. J. Plant Interact. 2022, 17, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, M.C.; Cuevas, R.P.; Ynion, J.; Laborte, A.G.; Velasco, M.L.; Demont, M. Rice quality: How is it defined by consumers, industry, food scientists, and geneticists? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asibi, A.E.; Chai, Q.; Coulter, J.A. Rice Blast: A Disease with Implications for Global Food Security. Agronomy 2019, 9, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.I.; Bhuiyan, M.R.; Hossain, M.S.; Sen, P.P.; Ara, A.; Siddique, M.A.; Ali, M.A. Neck blast disease influences grain yield and quality traits of aromatic rice. Comptes Rendus. Biol. 2014, 337, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Sahu, K.P.; Mehta, S.; Javed, M.; Balamurugan, A.; Ashajyothi, M.; Sheoran, N.; Ganesan, P.; Kundu, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; et al. New Insights on Endophytic Microbacterium-Assisted Blast Disease Suppression and Growth Promotion in Rice: Revelation by Polyphasic Functional Characterization and Transcriptomics. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongcharoen, N.; Kaewsalong, N.; Dethoup, T. Efficacy of fungicides in controlling rice blast and dirty panicle diseases in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepbandit, W.; Srisuwan, A.; Siriwong, S.; Nawong, S.; Athinuwat, D. Bacillus vallismortis TU-Orga21 blocks rice blast through both direct effect and stimulation of plant defense. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; de Jonge, R.; Berendsen, R.L. The Soil-Borne Legacy. Cell 2018, 172, 1178–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringlis, I.A.; Zhang, H.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Bolton, M.D.; de Jonge, R. Microbial small molecules-weapons of plant subversion. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018, 35, 410–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Luo, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Tian, C.; Tian, L. Culturable Screening of Plant Growth-Promoting and Biocontrol Bacteria in the Rhizosphere and Phyllosphere of Wild Rice. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, W.; Liu, M. Biocontrol potential of endophytic Bacillus velezensis strain QSE-21 against postharvest grey mould of fruit. Biol. Control 2021, 161, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, M.; Shankar, S.R.M.; MubarakAli, D.; Hari, B.N.V. A Novel Rhizospheric Bacterium: Bacillus velezensis NKMV-3 as a Biocontrol Agent Against Alternaria Leaf Blight in Tomato. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.H.; Yao, X.F.; Mi, D.D.; Li, Z.J.; Yang, B.Y.; Zheng, Y.; Qi, Y.J.; Guo, J.H. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Biocontrol Mechanism of Bacillus velezensis F21 Against Fusarium Wilt on Watermelon. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.; Johnson, C.; Santos-Medellín, C.; Lurie, E.; Podishetty, N.K.; Bhatnagar, S.; Eisen, J.A.; Sundaresan, V. Structure, variation, and assembly of the root-associated microbiomes of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E911–E920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-S.; Wang, F.-G.; Qi, Z.-Q.; Qiao, J.-Q.; Du, Y.; Yu, J.-J.; Yu, M.-N.; Liang, D.; Song, T.-Q.; Yan, P.-X.; et al. Iturins produced by Bacillus velezensis Jt84 play a key role in the biocontrol of rice blast disease. Biol. Control 2022, 174, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriss, R.; Danchin, A.; Harwood, C.R.; Médigue, C.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Sekowska, A.; Vallenet, D. Bacillus subtilis, the model Gram-positive bacterium: 20 years of annotation refinement. Microb. Biotechnol. 2018, 11, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Exploring Elicitors of the Beneficial Rhizobacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 to Induce Plant Systemic Resistance and Their Interactions With Plant Signaling Pathways. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2018, 31, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Koumoutsi, A.; Scholz, R.; Schneider, K.; Vater, J.; Süssmuth, R.; Piel, J.; Borriss, R. Genome analysis of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 reveals its potential for biocontrol of plant pathogens. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 140, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ju, W.; Chen, H.; Yue, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; et al. Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry reveals microbial phosphorus limitation decreases the nitrogen cycling potential of soils in semi-arid agricultural ecosystems. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 197, 104463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Li, Q.; Fu, R.; Wang, J.; Lu, D.; Chen, C. The Reorganization of Rice Rhizosphere Microbial Communities Driven by Nitrogen Utilization Efficiency and the Regulatory Mechanism of Soil Nitrogen Cycling. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ge, T.; Xiao, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Shibistova, O.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Inubushi, K.; Guggenberger, G. Phosphorus content as a function of soil aggregate size and paddy cultivation in highly weathered soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 7494–7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavyalova, N.E.; Vasbieva, M.T.; Shishkov, D.G.; Ivanova, O.V. Content of Potassium Forms in the Profile of Soddy-Podzolic Soil of the Cis-Ural Region. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.L.; Ross, W.J.; Norman, R.J.; Slaton, N.A.; Wilson, C.E., Jr. Predicting Nitrogen Fertilizer Needs for Rice in Arkansas Using Alkaline Hydrolyzable-Nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Xing, J.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J. Soil available phosphorus content drives the spatial distribution of archaeal communities along elevation in acidic terrace paddy soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, S.; Fei, C.; Ding, X. Impacts of straw returning and N application on NH4+-N loss, microbially reducible Fe(III) and bacterial community composition in saline-alkaline paddy soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Su, H.; Li, W.; Lin, L.; Lin, W.; Luo, L. Effects of microbial community structure and its co-occurrence on the dynamic changes of physicochemical properties and free amino acids in the Cantonese soy sauce fermentation process. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Chen, X.; Su, H.; Xing, A.; Chen, G.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, B.; Fang, J. Phosphorus addition decreases soil fungal richness and alters fungal guilds in two tropical forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 175, 108836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Valencia, E.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, G.; Li, X. N2-fixing bacteria are more sensitive to microtopography than nitrogen addition in degraded grassland. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1240634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Peng, L.; Zou, L.; Liu, B.; Li, Q. Mitigating the effects of polyethylene microplastics on Pisum sativum L. quality by applying microplastics-degrading bacteria: A field study. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Subramanian, S.; Faith, J.J.; Gevers, D.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R.; Mills, D.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, J. The Intratumor Microbiota Signatures Associate With Subtype, Tumor Stage, and Survival Status of Esophageal Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 754788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Want, E.J.; Masson, P.; Michopoulos, F.; Wilson, I.D.; Theodoridis, G.; Plumb, R.S.; Shockcor, J.; Loftus, N.; Holmes, E.; Nicholson, J.K. Global metabolic profiling of animal and human tissues via UPLC-MS. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Pan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Shen, Q.; Yang, J.; Huang, L.; Shen, Z.; Li, R. Plant-microbe interactions influence plant performance via boosting beneficial root-endophytic bacteria. Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, T.; Yu, C. A review of factors affecting the soil microbial community structure in wetlands. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 46760–46768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Dai, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Yin, Y.; Lin, Q.; Hou, M.; Jin, H. Comprehensive quantitative evaluation and mechanism analysis of influencing factors on yield and quality of cultivated Gastrodia elata Blume. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, M.; Grube, M.; Castro, J.V., Jr.; Müller, H.; Berg, G. Bacterial taxa associated with the lung lichen Lobaria pulmonaria are differentially shaped by geography and habitat. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 329, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, D.; Zhao, J.-H.; Yan, L.; Feng, G.-Z.; Gao, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhao, L.-P. Soil pH is the primary factor driving the distribution and function of microorganisms in farmland soils in northeastern China. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Koper, P.; Żebracki, K.; Marczak, M.; Mazur, A. Genomic and Metabolic Characterization of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Isolated from Nodules of Clovers Grown in Non-Farmed Soil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkacz, A.; Poole, P. Role of root microbiota in plant productivity. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2167–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, L.W.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; de Hollander, M.; Mendes, R.; Tsai, S.M. Influence of resistance breeding in common bean on rhizosphere microbiome composition and function. ISME J. 2018, 12, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Sun, X.; Häggblom, M.M.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, E.; Xiao, T.; Gao, P.; Li, B.; et al. Metabolic potentials of members of the class Acidobacteriia in metal-contaminated soils revealed by metagenomic analysis. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Gu, J.; Wang, G.; Bol, R.; Yao, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, H. Soil pH controls the structure and diversity of bacterial communities along elevational gradients on Huangshan, China. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2024, 120, 103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Fang, J.; Chu, H.; Adams, J.M. Soil Microbial Network Complexity Varies With pH as a Continuum, Not a Threshold, Across the North China Plain. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 895687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu-Xu, L.; González-Hernández, A.I.; Camañes, G.; Vicedo, B.; Scalschi, L.; Llorens, E. Harnessing Green Helpers: Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria and Other Beneficial Microorganisms in Plant–Microbe Interactions for Sustainable Agriculture. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Kang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, C.; Tan, J.; Zhao, X.; Qi, G. Ralstonia solanacearum infection induces tobacco root to secrete chemoattractants to recruit antagonistic bacteria and defensive compounds to inhibit pathogen. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Acosta, M.U.; Stassen, M.J.J.; Qi, R.; de Jonge, R.; White, F.; Kramer, G.; Dong, L.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Stringlis, I.A. Arabidopsis root defense barriers support beneficial interactions with rhizobacterium Pseudomonas simiae WCS417. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 2021–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Vismans, G.; Yu, K.; Song, Y.; de Jonge, R.; Burgman, W.P.; Burmølle, M.; Herschend, J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Disease-induced assemblage of a plant-beneficial bacterial consortium. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mason, G.A. Modulating the rhizosphere microbiome by altering the cocktail of root secretions. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Zhao, J.; Wen, T.; Zhao, M.; Li, R.; Goossens, P.; Huang, Q.; Bai, Y.; Vivanco, J.M.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; et al. Root exudates drive the soil-borne legacy of aboveground pathogen infection. Microbiome 2018, 6, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reininger, V.; Martinez-Garcia, L.B.; Sanderson, L.; Antunes, P.M. Composition of fungal soil communities varies with plant abundance and geographic origin. AoB Plants 2015, 7, plv110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chai, X.; Lyu, H.N.; Fu, C.; Tang, H.; Shi, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, C. Chemical proteomics reveals an ISR-like response elicited by salicylic acid in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, M.A.; Naqvi, R.Z.; Amin, I.; Mansoor, S. Salicylic acid-driven innate antiviral immunity in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.H. Regulation of Salicylic Acid and N-Hydroxy-Pipecolic Acid in Systemic Acquired Resistance. Plant Pathol. J. 2023, 39, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minen, R.I.; Thirumalaikumar, V.P.; Skirycz, A. Proteinogenic dipeptides, an emerging class of small-molecule regulators. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2023, 75, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaray, F.; Felipo-Benavent, A.; Vera, P. Linking plant metabolism and immunity through methionine biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pH | OC (g/kg) | TN (g/kg) | TP (g/kg) | TK (g/kg) | HN (mg/kg) | AP (mg/kg) | AK (mg/kg) | NH4+–N (mg/kg) | NO3−–N (mg/kg) | NO2−–N (mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P104 | 5.90 ± 0.02 c | 29.63 ± 0.66 a | 2.86 ± 0.02 a | 0.74 ± 0.02 b | 13.53 ± 0.28 b | 266.93 ± 3.93 a | 1.21 ± 0.04 c | 98.67 ± 1.51 a | 4.73 ± 0.30 a | 1.32 ± 0.06 a | 0.08 ± 0.01 a |

| P206 | 5.97 ± 0.02 b | 29.22 ± 0.80 a | 2.78 ± 0.03 bc | 0.72 ± 0.02 b | 13.53 ± 0.15 b | 254.03 ± 1.68 b | 1.34 ± 0.04 b | 93.02 ± 1.54 b | 3.21 ± 0.17 b | 0.82 ± 0.04 c | 0.11 ± 0.01 b |

| P309 | 6.01 ± 0.03 b | 29.03 ± 0.23 a | 2.82 ± 0.04 ab | 0.79 ± 0.02 a | 14.51 ± 0.24 a | 263.34 ± 3.46 a | 1.17 ± 0.03 c | 92.35 ± 1.10 b | 4.66 ± 0.27 a | 0.56 ± 0.04 d | 0.11 ± 0.00 a |

| P302 | 6.24 ± 0.03 a | 29.34 ± 0.60 a | 2.74 ± 0.03 c | 0.82 ± 0.02 a | 13.70 ± 0.07 b | 266.30 ± 5.02 a | 1.49 ± 0.04 a | 96.58 ± 2.10 a | 3.67 ± 0.17 b | 1.10 ± 0.07 b | 0.11 ± 0.00 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Li, D.; Lu, D.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, R.; Huang, F. Differential Assembly of Rhizosphere Microbiome and Metabolome in Rice with Contrasting Resistance to Blast Disease. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2789. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122789

Wang J, Li D, Lu D, Chen C, Zhang Q, Fu R, Huang F. Differential Assembly of Rhizosphere Microbiome and Metabolome in Rice with Contrasting Resistance to Blast Disease. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2789. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122789

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jian, Deqiang Li, Daihua Lu, Cheng Chen, Qin Zhang, Rongtao Fu, and Fu Huang. 2025. "Differential Assembly of Rhizosphere Microbiome and Metabolome in Rice with Contrasting Resistance to Blast Disease" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2789. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122789

APA StyleWang, J., Li, D., Lu, D., Chen, C., Zhang, Q., Fu, R., & Huang, F. (2025). Differential Assembly of Rhizosphere Microbiome and Metabolome in Rice with Contrasting Resistance to Blast Disease. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2789. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122789