Macleaya cordata Alkaloids Sanguinarine and Chelerythrine Inhibit Nocardia seriolae by Disrupting Cell Envelope Integrity and Energy Metabolism: Insights from Transcriptomic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain and Reagents

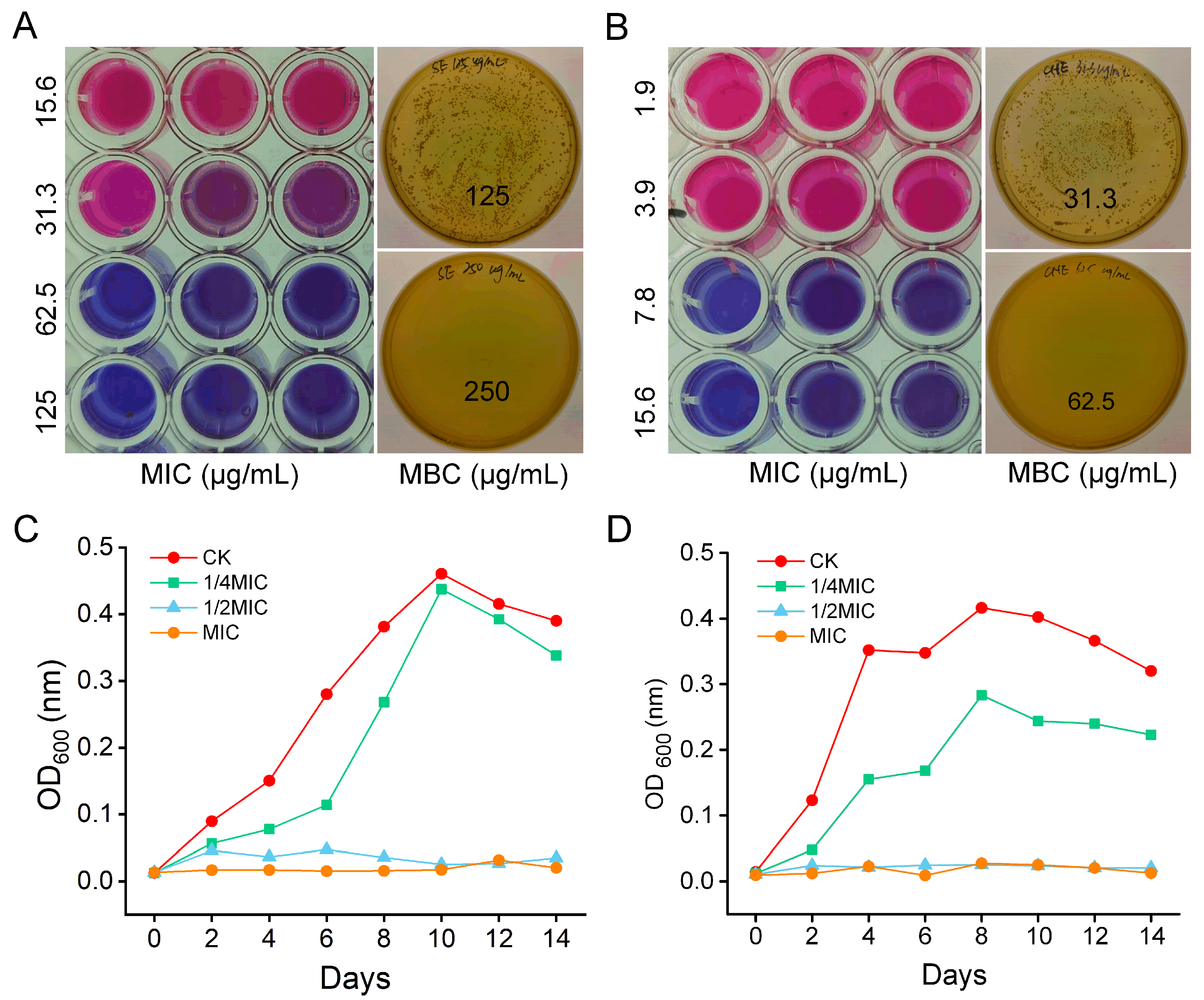

2.2. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity Assays

2.2.1. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory and Bactericidal Concentrations

2.2.2. Growth Curve Analysis

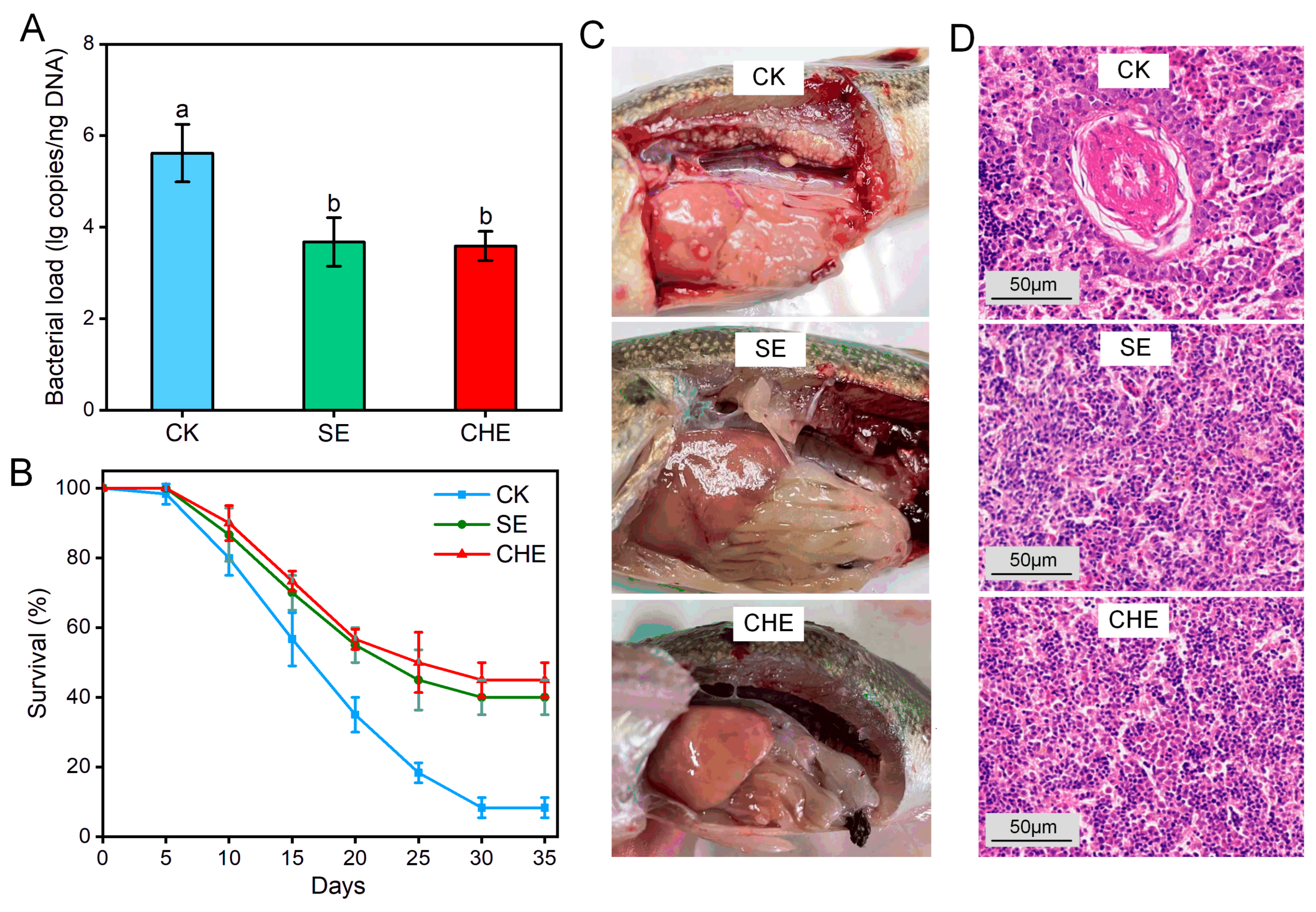

2.3. In Vivo Antibacterial Assays

2.3.1. Experimental Animals and Experimental Design

2.3.2. Sample Collection and Analysis

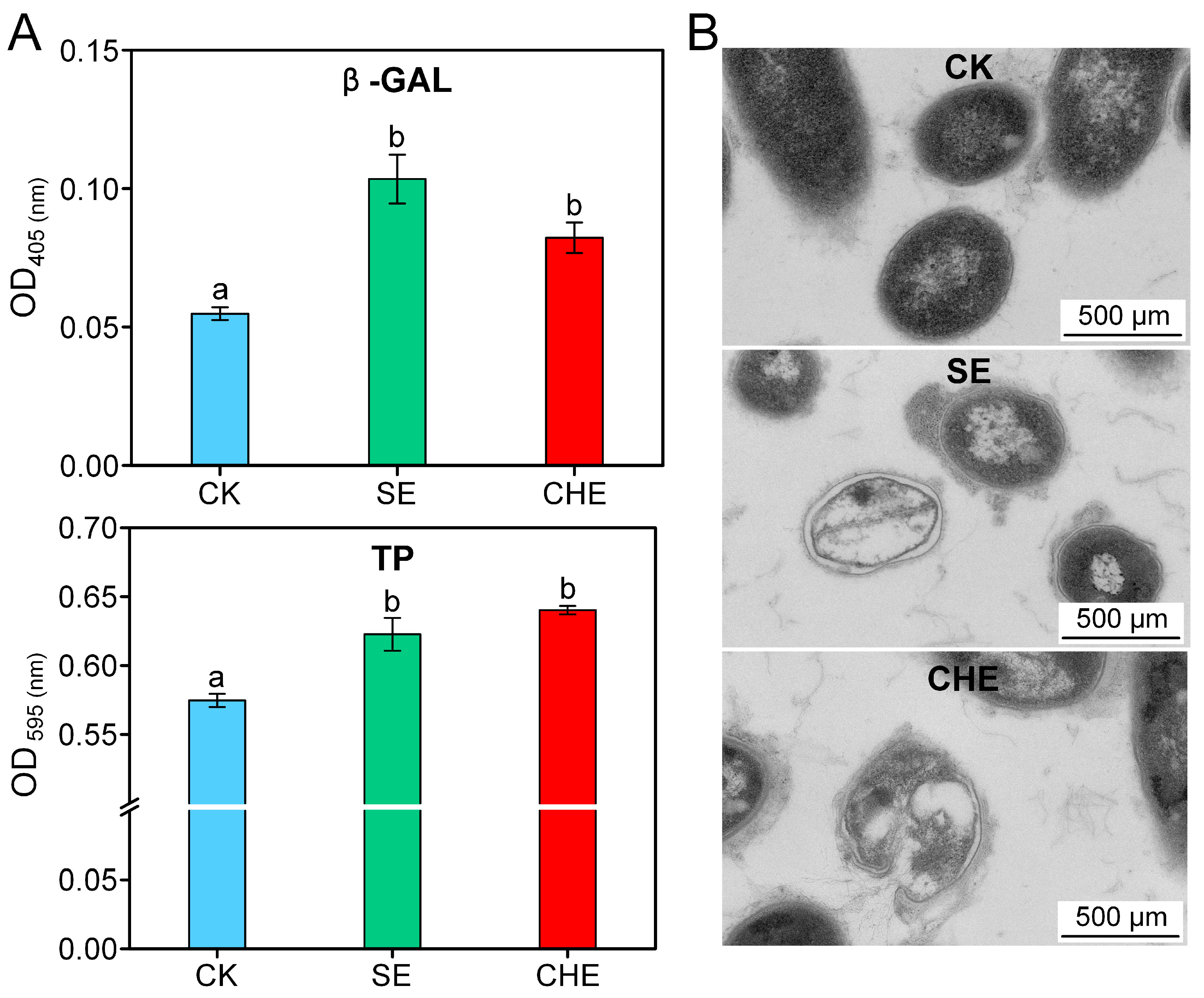

2.4. Cell Membrane Permeability and Ultrastructural Analysis

2.4.1. Membrane Permeability Assessment

2.4.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.5. Transcriptome Analysis

2.5.1. Sample Preparation, RNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.5.2. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Validation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity

3.2. In Vivo Antibacterial Effects

3.3. Effects of SE and CHE on Cell Structure of N. seriolae

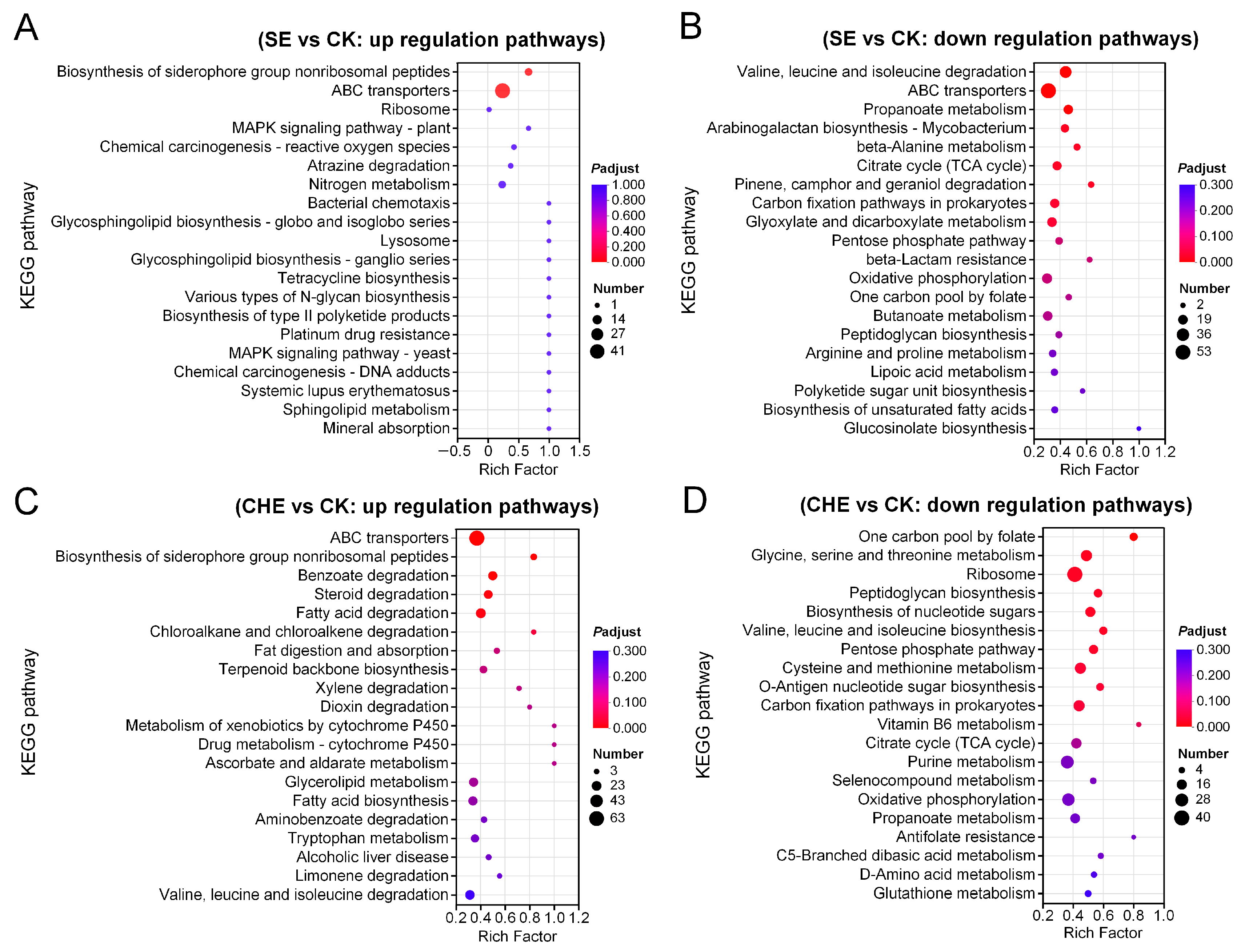

3.4. Transcriptome Results

3.4.1. Transcriptome Data Overview

3.4.2. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

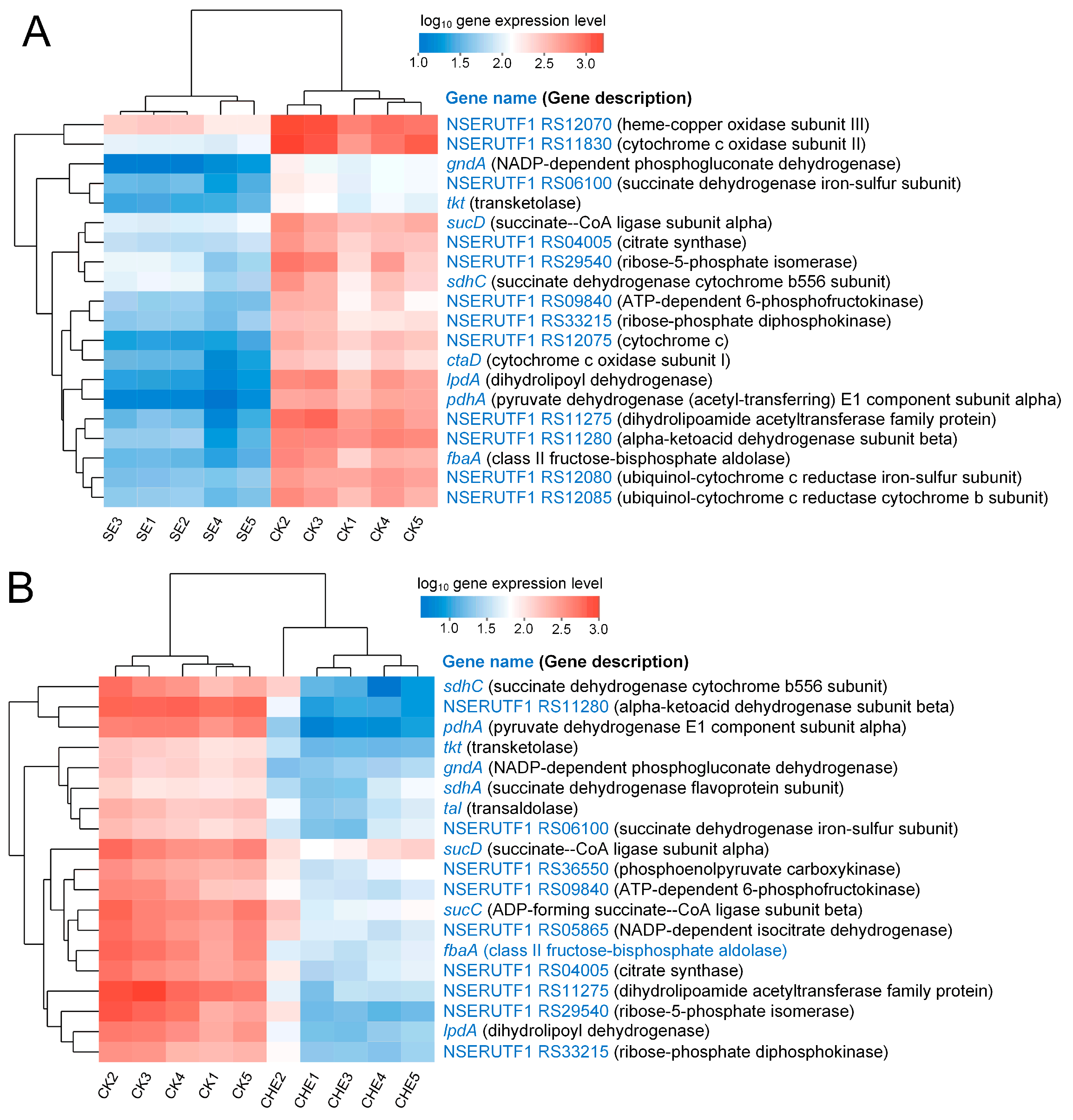

3.4.3. Clustering Analysis of Genes Enriched in Energy Metabolism Related Pathways

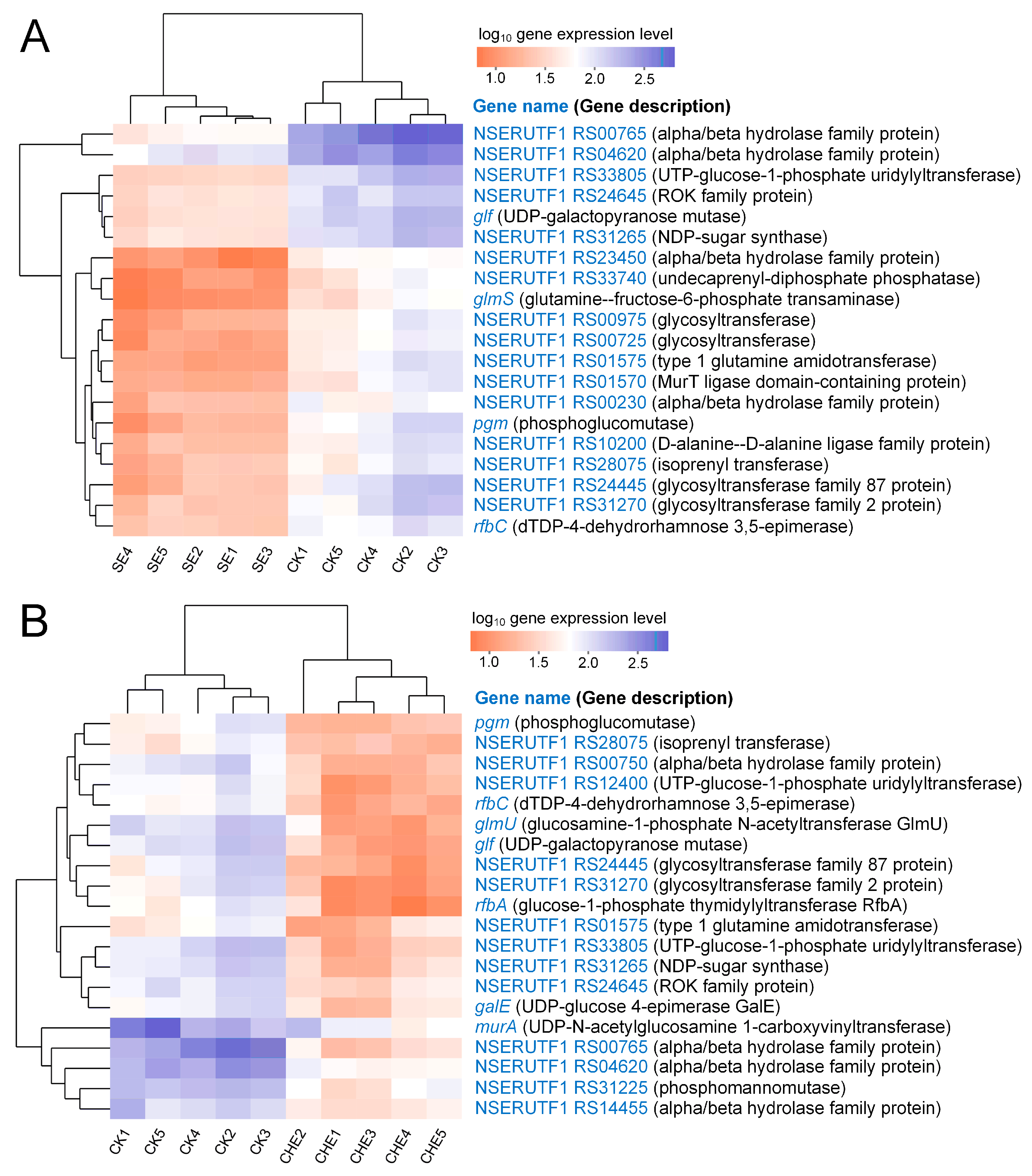

3.4.4. Clustering Analysis of Genes Enriched in Cell Wall Biosynthesis Related Pathways

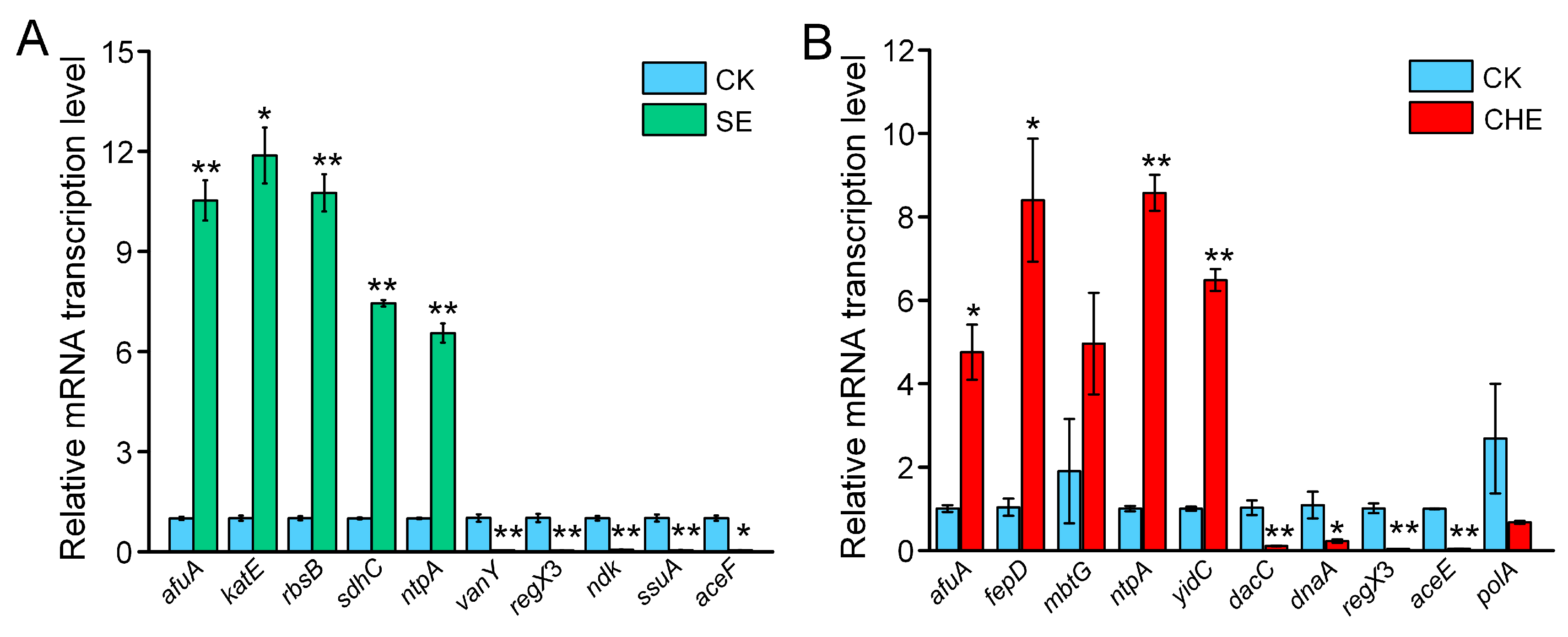

3.5. RT-qPCR Validation

4. Discussion

4.1. SE and CHE Exhibit Potent Antibacterial Activity Against N. seriolae

4.2. SE and CHE Disrupt Cellular Structure and Suppress Cell Wall Biosynthesis in N. seriolae

4.3. SE and CHE Impair Energy Metabolism in N. seriolae

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lei, X.; Zhao, R.; Geng, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, P.O.; Chen, D.; Huang, X.; Zuo, Z.; He, C.; Chen, Z. Nocardia seriolae: A serious threat to the largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides industry in Southwest China. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2020, 142, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Xia, L.; Lu, Y. A review on the pathogenic bacterium Nocardia seriolae: Aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and vaccine development. Rev. Aquacult. 2023, 15, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Bai, S.; He, J.; Xiong, Q.; Zhong, Z.; Lu, C.; Kuang, L.; Jian, Z.; Gu, J.; Liu, M. Pathogenicity, ultrastructure and genomics analysis of Nocardia seriolae isolated from largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Microb. Pathog. 2025, 205, 107715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Deng, Y.; Tan, A.; Zhao, F.; Chang, O.; Wang, F.; Lai, Y.; Huang, Z. Intracellular behavior of Nocardia seriolae and its apoptotic effect on RAW264. 7 macrophages. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1138422. [Google Scholar]

- Bulfon, C.; Volpatti, D.; Galeotti, M. Current research on the use of plant-derived products in farmed fish. Aquac. Res. 2015, 46, 513–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosina, P.; Gregorova, J.; Gruz, J.; Vacek, J.; Kolar, M.; Vogel, M.; Roos, W.; Naumann, K.; Simanek, V.; Ulrichova, J. Phytochemical and antimicrobial characterization of Macleaya cordata herb. Fitoterapia 2010, 81, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wu, S. Natural antibacterial and antivirulence alkaloids from Macleaya cordata against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 813172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussabong, P.; Rairat, T.; Chuchird, N.; Keetanon, A.; Phansawat, P.; Cherdkeattipol, K.; Pichitkul, P.; Kraitavin, W. Effects of isoquinoline alkaloids from Macleaya cordata on growth performance, survival, immune response, and resistance to Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; Luo, Q.; Dong, X.; Tang, G.; Zhang, J.; Du, X.; Pu, Q.; He, L. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of sanguinarine against Staphylococcus aureus by interfering with the permeability of the cell wall and membrane and inducing bacterial ROS production. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1121082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, J.; Pu, Q.; Wang, R.; Gu, Y.; He, L.; Du, X.; Tang, G.; Han, D. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of chelerythrine against Streptococcus agalactiae. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1408376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, W.; Yang, M.; Li, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, T. Anti-microbial and anti-biofilm activities of combined chelerythrine-sanguinarine and mode of action against Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans in vitro. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 191, 111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, N.; Li, C. Comprehensive analysis of long noncoding RNAs and lncRNA-mRNA networks in snakehead (Channa argus) response to Nocardia seriolae infection. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2023, 133, 108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Sun, Y.; Qian, Y.; Chen, Q.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Han, T.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Y. Integrated analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveals the regulatory mechanism of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) in response to Nocardia seriolae infection. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2024, 145, 109322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, K.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J. Comprehensive profiling of lncRNAs in the immune response of largemouth bass to Nocardia Seriolae infection. Comp. Immunol. Rep. 2024, 7, 200165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, N.; Liu, X.; Cao, M.; Li, C. Comprehensive analysis of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks in the kidney of snakehead (Channa argus) response to Nocardia seriolae challenge. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2024, 151, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Ren, X.; Cao, G.; Zhou, X.; Jin, L. Transcriptome analysis on the mechanism of ethylicin inhibiting Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae on kiwifruit. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y.; Pei, H.; Cao, X. Inhibitory effect of Lonicera japonica flos on Streptococcus mutans biofilm and mechanism exploration through metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1435503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, T.F.; Nakamura, A.; Nakanishi, K.; Minami, T.; Murase, T.; Yanagi, S.; Itami, T.; Yoshida, T. Modified resazurin microtiter assay for in vitro and in vivo assessment of sulfamonomethoxine activity against the fish pathogen Nocardia seriolae. Fish. Sci. 2012, 78, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Lin, L.; Huang, L.; Mu, X.; Wang, C.; Yao, J.; Lao, S.; Shen, J. Establishment and evolutionary analysis of a qPCR assay for Nocardia seriolae based on the SecA gene. Acta. Hydrobiol. Sin. 2023, 47, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Kolev, P.; Rocha-Mendoza, D.; Ruiz-Ramírez, S.; Ortega-Anaya, J.; Jiménez-Flores, R.; García-Cano, I. Screening and characterization of β-galactosidase activity in lactic acid bacteria for the valorization of acid whey. JDS Commun. 2022, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Lai, J.; Wang, J. The minimum inhibitory concentration of antibiotics against Nocardia seriolae isolation from diseased fish in Taiwan. Taiwan Vet. J. 2016, 42, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, L.d.C.; Zanon, G.; Weber, A.D.; Neto, A.T.; Mostardeiro, C.P.; Da Cruz, I.B.M.; Oliveira, R.M.; Ilha, V.; Dalcol, I.I.; Morel, A.F. Structure-activity relationship of benzophenanthridine alkaloids from Zanthoxylum rhoifolium having antimicrobial activity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Q.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Cui, W.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z. Targeting membrane integrity and imidazoleglycerol-phosphate dehydratase: Sanguinarine multifaceted approach against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Phytomedicine 2025, 138, 156428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yan, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, E.; Wang, G. Dietary sanguinarine enhances disease resistance to Aeromonas dhakensis in Largemouth (Micropterus salmoides). Fish Shellfish Immun. 2025, 165, 110577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, N.; Cui, D.; Zhao, M. Antibacterial Effect and Mechanism of Chelerythrine on Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, L.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ai, X.; Dong, J. Sanguinarine protects channel catfish against Aeromonas hydrophila infection by inhibiting aerolysin and biofilm formation. Pathogens 2022, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Huang, L.; Zhai, S. Effects of Macleaya cordata extract on growth performance, serum biochemical parameters, and intestinal health of juvenile American eel (Anguilla rostrata). Fishes 2022, 7, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhu, R.; Huan, D.; Li, X.; Leng, X. Effects of Macleaya cordata extract supplementation in low-protein, low-fishmeal diets on growth, hematology, intestinal histology, and microbiota in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Aquacult. Rep. 2025, 40, 102618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Tang, S.; Ma, X.; Li, C.; Tang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, J. Preclinical safety evaluation of Macleaya cordata extract: A re-assessment of general toxicity and genotoxicity properties in rodents. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 980918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Rutherford, S.T.; Silhavy, T.J.; Huang, K.C. Physical properties of the bacterial outer membrane. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderwick, L.J.; Harrison, J.; Lloyd, G.S.; Birch, H.L. The mycobacterial cell wall—Peptidoglycan and arabinogalactan. CSH Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a021113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.D.; Vivas, E.I.; Walsh, C.T.; Kolter, R. MurA (MurZ), the enzyme that catalyzes the first committed step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis, is essential in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 4194–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lyu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, N.; Wen, Z.; Chen, S. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of sanguinarine against Providencia rettgeri in vitro. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkessel, M.; Basta, D.W.; Newman, D.K. The physiology of growth arrest: Uniting molecular and environmental microbiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Sha, H.; Bi, W.; Zeng, J.; Su, D. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of the antibacterial mechanism of sanguinarine against Enterobacter cloacae in vitro. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.R. Virulence and metabolism. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirody, J.A.; Budin, I.; Rangamani, P. ATP synthase: Evolution, energetics, and membrane interactions. J. Gen. Physiol. 2020, 152, e201912475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Tm Value |

|---|---|---|

| afuA | F: GGCCAAGACCAAGGAGAACA | 59.89 |

| R: TCAGGAACTTCTGGGCGTTG | 60.25 | |

| urtA | F: AGCAATACCAGCTACGAGGC | 59.89 |

| R: TTGATTGCCCTCGAAACCGA | 59.96 | |

| katE | F: TGGTTACCGGTGATGTGAGC | 60.04 |

| R: GGTGTAGAACTTCACCGCGA | 60.04 | |

| sdhC | F: CATCGCGCTGTATCTGGTCT | 59.97 |

| R: GCCAGGACATAGAACACCGT | 59.75 | |

| ntpA | F: ACGCGGATGTGATCGTCTAC | 59.97 |

| R: GCCATATTGGAGGTGTTGGC | 59.25 | |

| tauA | F: GGCGAATACGCCTACCTGAA | 59.90 |

| R: TGGCAAGACCCTGAATCTCG | 59.75 | |

| mbtG | F: CTGGACCTTTTCGACACCGA | 59.97 |

| R: CCAGATTCGGCAGGTAGAGC | 60.25 | |

| RegX3 | F: CTGCTCGATCTCATGCTCCC | 60.32 |

| R: CACCTTGTCGATCTCGCTGT | 60.11 | |

| acd | F: TGCTGGGTCTGACAAAGACG | 60.25 |

| R: TGGTAGGGGATCGACAGCAT | 60.40 | |

| ndk | F: AGATCATCACCCGCATCGAG | 59.68 |

| R: ATTCGATGAGCGAGCCGAAG | 60.60 | |

| pstS | F: GTGAATCTCAAGCGCAGCAG | 59.90 |

| R: GGTCCATGGCGTTCTTCTGA | 60.04 | |

| 16S | F: AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | 55.40 |

| R: TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT | 55.81 |

| Sample Name | Raw Error Rate (%) | Clean Reads | Clean Q20 (%) | Genome Mapped Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE1 | 0.014 | 24, 397, 522 | 98.01 | 96.18 |

| SE2 | 0.014 | 25, 413, 870 | 98.02 | 96.44 |

| SE3 | 0.014 | 24, 691, 366 | 97.95 | 95.93 |

| SE4 | 0.013 | 23, 601, 956 | 98.37 | 98.08 |

| SE5 | 0.013 | 24, 801, 536 | 98.38 | 97.39 |

| CHE1 | 0.017 | 27, 114, 160 | 96.75 | 98.11 |

| CHE2 | 0.014 | 21, 313, 624 | 98.21 | 96.48 |

| CHE3 | 0.018 | 34, 308, 280 | 96.30 | 96.95 |

| CHE4 | 0.016 | 23, 894, 644 | 97.37 | 97.36 |

| CHE5 | 0.016 | 28, 653, 500 | 97.62 | 98.37 |

| CK1 | 0.013 | 25, 211, 102 | 98.35 | 98.27 |

| CK2 | 0.014 | 24, 457, 136 | 98.30 | 96.48 |

| CK3 | 0.014 | 25, 376, 278 | 98.25 | 96.83 |

| CK4 | 0.014 | 28, 698, 816 | 98.28 | 97.20 |

| CK5 | 0.013 | 23, 629, 998 | 98.42 | 97.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, L.; Cai, X.; Chu, K.; Yuan, X.; Peng, X.; Chen, J.; Bu, X.; Niu, C.; Song, D.; Yao, J. Macleaya cordata Alkaloids Sanguinarine and Chelerythrine Inhibit Nocardia seriolae by Disrupting Cell Envelope Integrity and Energy Metabolism: Insights from Transcriptomic Analysis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2790. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122790

Huang L, Cai X, Chu K, Yuan X, Peng X, Chen J, Bu X, Niu C, Song D, Yao J. Macleaya cordata Alkaloids Sanguinarine and Chelerythrine Inhibit Nocardia seriolae by Disrupting Cell Envelope Integrity and Energy Metabolism: Insights from Transcriptomic Analysis. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2790. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122790

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Lei, Xue Cai, Kuan Chu, Xuemei Yuan, Xianqi Peng, Jing Chen, Xialian Bu, Chen Niu, Dawei Song, and Jiayun Yao. 2025. "Macleaya cordata Alkaloids Sanguinarine and Chelerythrine Inhibit Nocardia seriolae by Disrupting Cell Envelope Integrity and Energy Metabolism: Insights from Transcriptomic Analysis" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2790. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122790

APA StyleHuang, L., Cai, X., Chu, K., Yuan, X., Peng, X., Chen, J., Bu, X., Niu, C., Song, D., & Yao, J. (2025). Macleaya cordata Alkaloids Sanguinarine and Chelerythrine Inhibit Nocardia seriolae by Disrupting Cell Envelope Integrity and Energy Metabolism: Insights from Transcriptomic Analysis. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2790. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122790