Bacterial Adaptation to Stress Induced by Glyoxal/Methylglyoxal and Advanced Glycation End Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

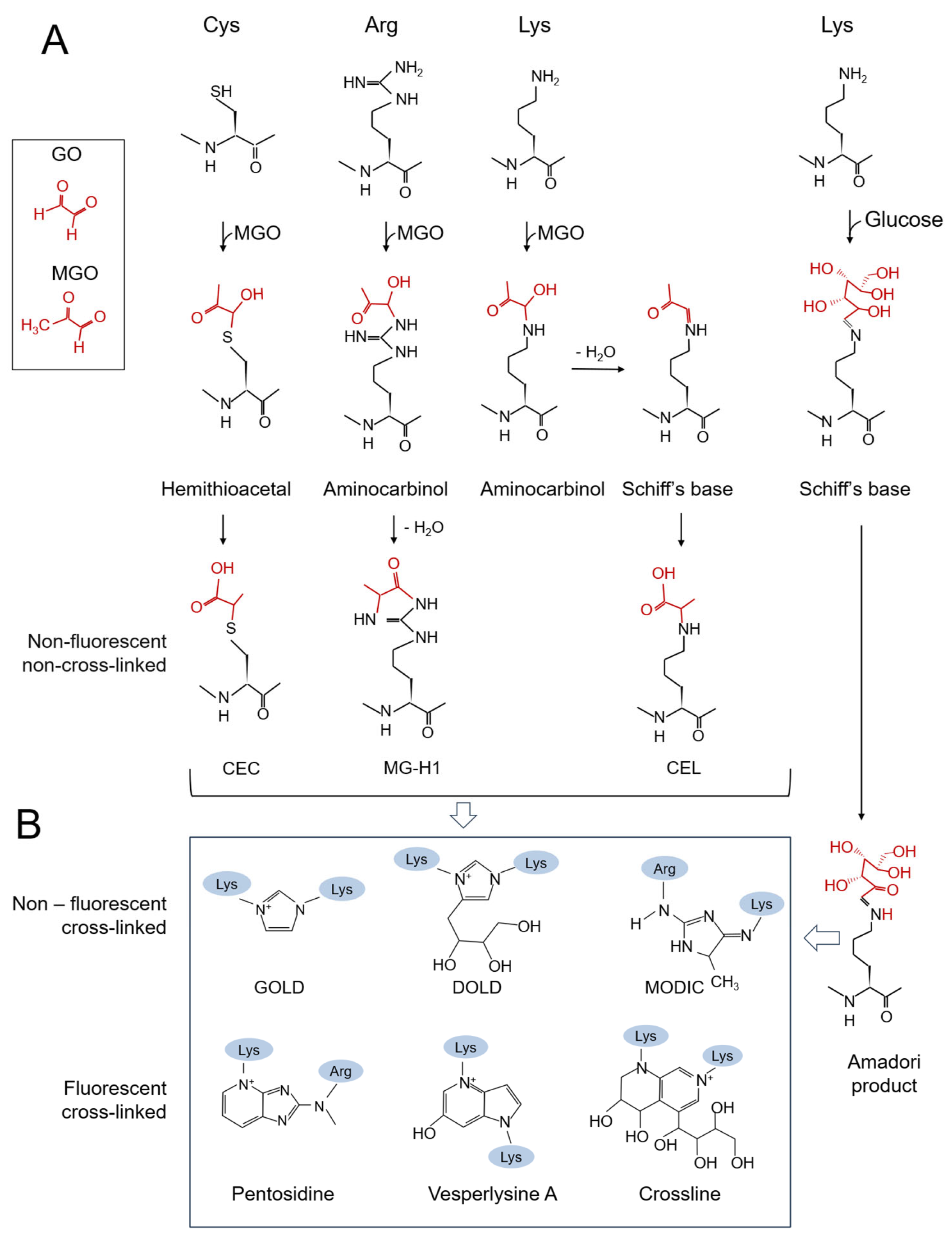

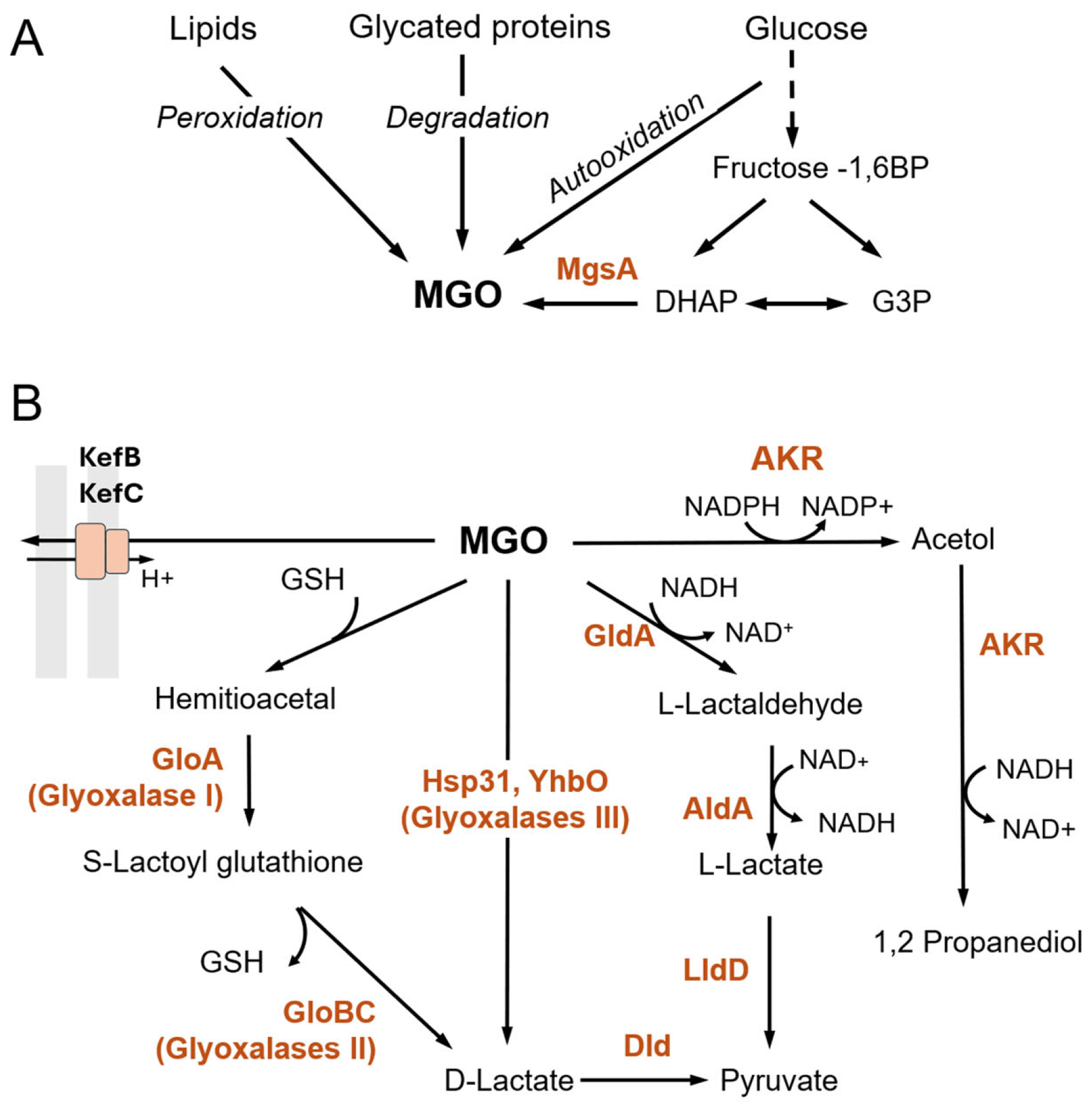

2. Production and Toxic Effects of GO/MGO and AGEs in Bacteria

3. Detoxification of GO/MGO

3.1. Glutathione-Dependent Pathway

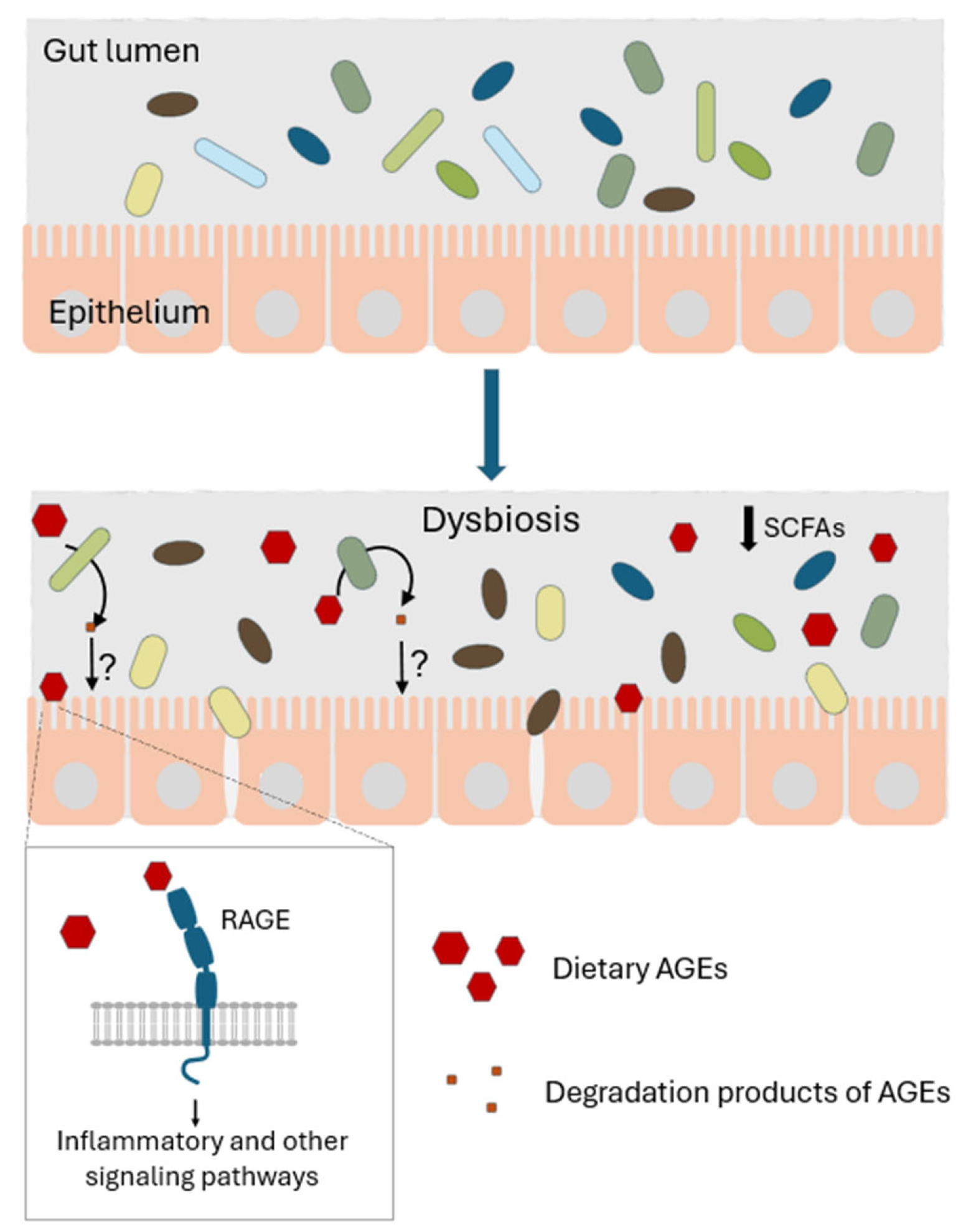

3.2. Glutathione-Independent Pathways

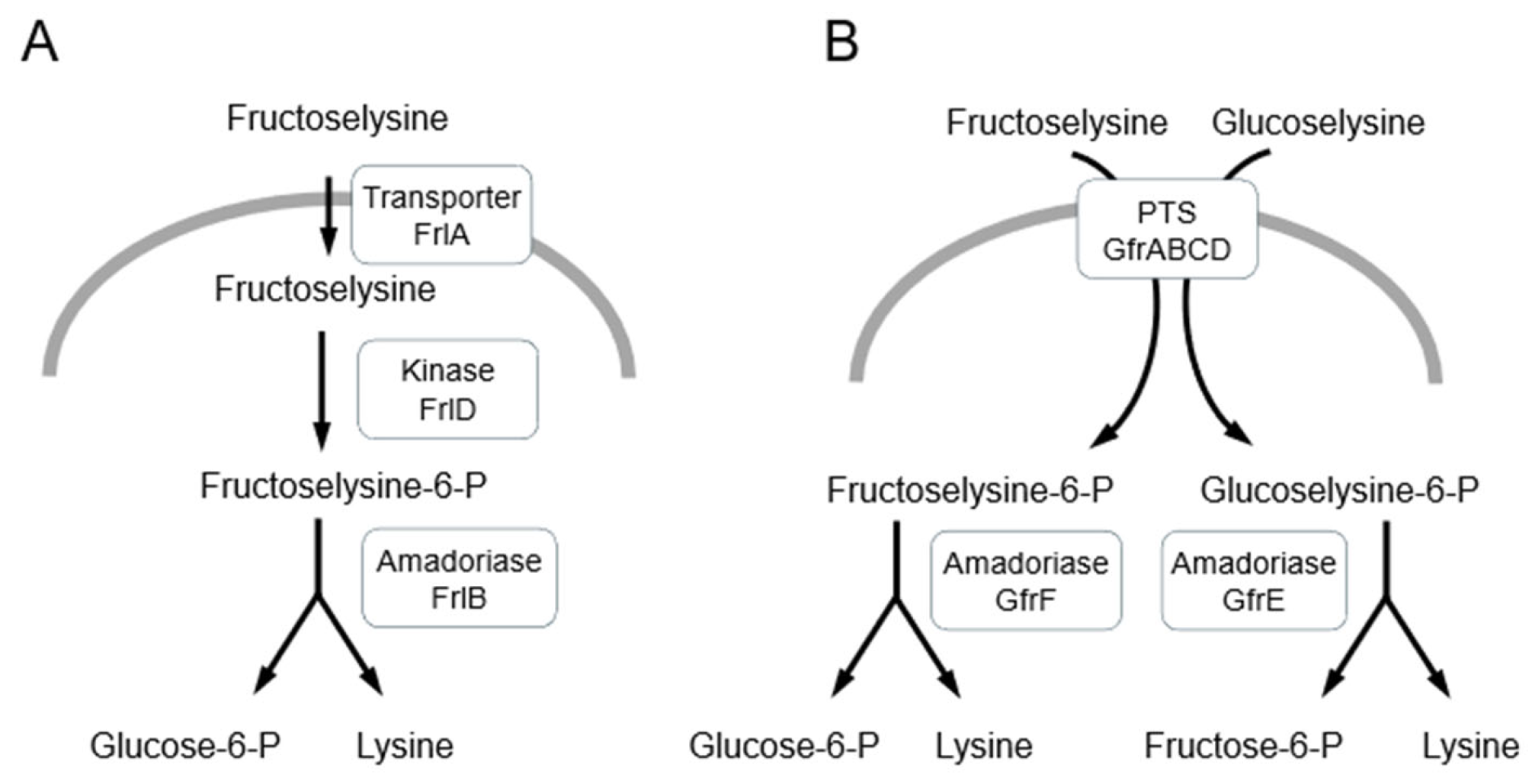

4. Detoxification of Amadori Products and AGEs in Bacteria

5. Small Molecule Inhibitors of Glycation

6. Gut Microbiota and Dietary AGEs

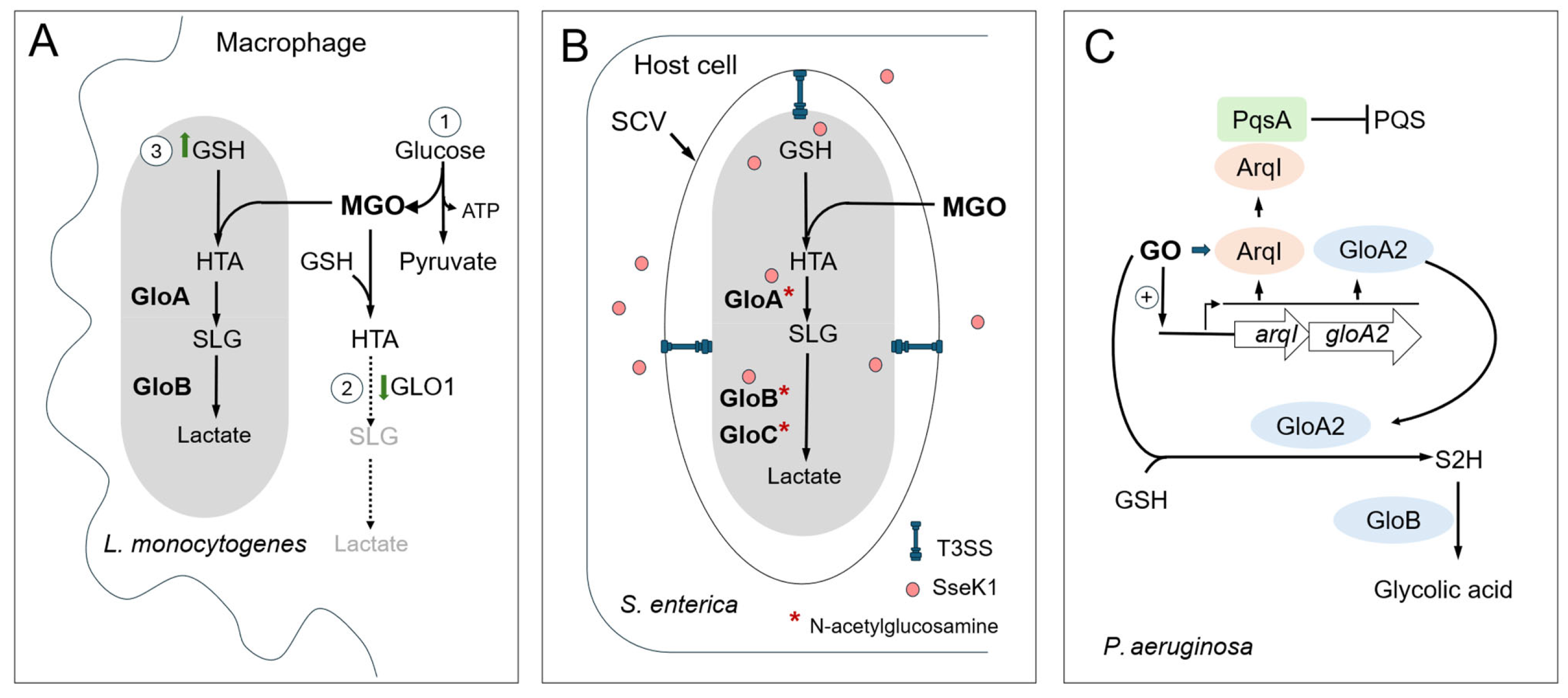

7. Host-Derived MGO/GO as an Antibacterial Agents

7.1. MGO/GO Production in Mammalian Cells

7.2. Glyoxalase Pathway as a Way to Evade Host Response

7.3. Glyoxalase Pathway and Interspecies Competition in Oral Streptococci

8. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGEs | Advanced Glycation End products |

| AKR | Aldo-keto reductase |

| CEC | Carboxyethyl cysteine |

| CEL | Carboxyethyl lysine |

| CML | Carboxymethyl lysine |

| DHAP | Dihydroxyacetone phosphate |

| DOLD | Deoxyglucosone-derived lysine dimer |

| G3P | Glycerol-3-phosphate |

| GO | Glyoxal |

| GOLD | Glyoxal-derived lysine dimer |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HSA | Human serum albumin |

| MG-H1 | Methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone-1 |

| MGO | Methylglyoxal |

| MODIC | Methylglyoxal-derived imidazolium cross-link |

| PTS | Phosphotransferase system |

| RAGE | Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products |

| RES | Reactive electrophile species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

References

- Lee, C.; Park, C. Bacterial responses to glyoxal and methylglyoxal: Reactive electrophilic species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twarda-Clapa, A.; Olczak, A.; Białkowska, A.M.; Koziołkiewicz, M. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs): Formation, chemistry, classification, receptors, and diseases related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.W.T.; Lopez Gonzalez, E.D.J.; Zoukari, T.; Ki, P.; Shuck, S.C. Methylglyoxal and its adducts: Induction, repair, and association with disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1720–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uceda, A.B.; Mariño, L.; Casasnovas, R.; Adrover, M. An overview on glycation: Molecular mechanisms, impact on proteins, pathogenesis, and inhibition. Biophys. Rev. 2024, 16, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordiienko, I. Carbonyl stress chemistry. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2024, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hosry, L.; Elias, V.; Chamoun, V.; Halawi, M.; Cayot, P.; Nehme, A.; Bou-Maroun, E. Maillard reaction: Mechanism, influencing parameters, advantages, disadvantages, and food industrial applications: A review. Foods 2025, 14, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séro, L.; Sanguinet, L.; Blanchard, P.; Dang, B.T.; Morel, S.; Richomme, P.; Séraphin, D.; Derbré, S. Tuning a 96-well microtiter plate fluorescence-based assay to identify age inhibitors in crude plant extracts. Molecules 2013, 18, 14320–14339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, C.; Irace, G.; Sirangelo, I. Differential effects of glycation on protein aggregation and amyloid formation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2014, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, N.; Thornalley, P.J. Protein glycation–biomarkers of metabolic dysfunction and early-stage decline in health in the era of precision medicine. Redox Biol. 2021, 42, 101920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournet, M.; Bonté, F.; Desmoulière, A. Glycation damage: A possible hub for major pathophysiological disorders and aging. Aging Dis. 2018, 9, 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata-Kamiya, N.; Kamiya, H. Methylglyoxal, an endogenous aldehyde, crosslinks DNA polymerase and the substrate DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, 3433–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pischetsrieder, M.; Seidel, W.; Münch, G.; Schinzel, R. N2-(1-carboxyethyl)deoxyguanosine, a nonenzymatic glycation adduct of DNA, induces single-strand breaks and increases mutation frequencies. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 264, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Monnier, V.M. Protein posttranslational modification (PTM) by glycation: Role in lens aging and age-related cataractogenesis. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 210, 108705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, N.; Thornalley, P.J. Dicarbonyl stress in cell and tissue dysfunction contributing to ageing and disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 458, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vašková, J.; Kováčová, G.; Pudelský, J.; Palenčár, D.; Mičková, H. Methylglyoxal formation—Metabolic routes and consequences. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kold-Christensen, R.; Johannsen, M. Methylglyoxal metabolism and aging-related disease: Moving from correlation toward causation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.-X.; Requena, J.R.; Jenkins, A.J.; Lyons, T.J.; Baynes, J.W.; Thorpe, S.R. The advanced glycation end product, N-(carboxymethyl)lysine, is a product of both lipid peroxidation and glycoxidation reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 9982–9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, K.; Jung, T.; Höhn, A.; Weber, D.; Grune, T. Advanced glycation end products and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bari, L.; Scirè, A.; Minnelli, C.; Cianfruglia, L.; Kalapos, M.P.; Armeni, T. Interplay among oxidative stress, methylglyoxal pathway and s-glutathionylation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppe, V.M.; Bongaerts, J.; O’Connell, T.; Maurer, K.H.; Meinhardt, F. Enzymatic deglycation of Amadori products in bacteria: Mechanisms, occurrence and physiological functions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironova, R.; Niwa, T.; Hayashi, H.; Dimitrova, R.; Ivanov, I. Evidence for non-enzymatic glycosylation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironova, R.; Niwa, T.; Handzhiyski, Y.; Sredovska, A.; Ivanov, I. Evidence for non-enzymatic glycosylation of Escherichia coli chromosomal DNA. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacometti, C.; Marx, K.; Hönick, M.; Biletskaia, V.; Schulz-Mirbach, H.; Dronsella, B.; Satanowski, A.; Delmas, V.A.; Berger, A.; Dubois, I.; et al. Activating silent glycolysis bypasses in Escherichia coli. BioDes. Res. 2022, 2022, 9859643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, I.R.; Ferguson, G.P.; Miller, S.; Li, C.; Gunasekera, B.; Kinghorn, S. Bacterial production of methylglyoxal: A survival strategy or death by misadventure? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003, 31, 1404–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornalley, P.J.; Langborg, A.; Minhas, H.S. Formation of glyoxal, methylglyoxal and 3-deoxyglucosone in the glycation of proteins by glucose. Biochem. J. 1999, 344, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boteva, E.; Mironova, R. Maillard reaction and aging: Can bacteria shed light on the link? Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2019, 33, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, E.D.; Farrell, M.J.; Nord, G.; Finkel, S.E. Antiglycation effects of carnosine and other compounds on the long-term survival of Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 7925–7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kram, K.E.; Finkel, S.E. Rich medium composition affects Escherichia coli survival, glycation, and mutation frequency during long-term batch culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 4442–4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łupkowska, A.; Monem, S.; Dębski, J.; Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K.; Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D.; Laskowska, E. Protein aggregation and glycation in Escherichia coli exposed to desiccation-rehydration stress. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 270, 127335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbelin, J.; Santos, T.; Hébraud, M. Desiccation: An environmental and food industry stress that bacteria commonly face. Food Microbiol. 2018, 69, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzyb, T.; Skłodowska, A. Introduction to bacterial anhydrobiosis: A general perspective and the mechanisms of desiccation-associated damage. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowska, E.; Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D. New insight into the mechanisms protecting bacteria during desiccation. Curr. Genet. 2020, 66, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebre, P.H.; De Maayer, P.; Cowan, D.A. Xerotolerant bacteria: Surviving through a dry spell. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilova, T.; Paudel, G.; Shilyaev, N.; Schmidt, R.; Brauch, D.; Tarakhovskaya, E.; Milrud, S.; Smolikova, G.; Tissier, A.; Vogt, T.; et al. Global proteomic analysis of advanced glycation end products in the Arabidopsis proteome provides evidence for age-related glycation hot spots. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 15758–15776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazi, I.; Franc, V.; Tamara, S.; van Gool, M.P.; Huppertz, T.; Heck, A.J.R. Identifying glycation hot-spots in bovine milk proteins during production and storage of skim milk powder. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 129, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, F.; Ortiz-Suarez, M.L.; Piggot, T.J.; Bond, P.J.; Khalid, S. OmpA: A flexible clamp for bacterial cell wall attachment. Structure 2016, 24, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baslé, A.; Rummel, G.; Storici, P.; Rosenbusch, J.P.; Schirmer, T. Crystal structure of osmoporin OmpC from E. coli at 2.0 Å. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 362, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, G.P.; Battista, J.R.; Annettee, T.L.; Booth, I.R. Protection of the DNA during the exposure of Escherichia coli cells to a toxic metabolite: The role of the KefB and KefC potassium channels. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 35, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, G.P.; Nikolaev, Y.; McLaggan, D.; Maclean, M.; Booth, I.R. Survival during exposure to the electrophilic reagent N-ethylmaleimide in Escherichia coli: Role of KefB and KefC potassium channels. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosild, T.P.; Castronovo, S.; Healy, J.; Miller, S.; Pliotas, C.; Rasmussen, T.; Bartlett, W.; Conway, S.J.; Booth, I.R. Mechanism of ligand-gated potassium efflux in bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19784–19789, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T. The potassium efflux system Kef: Bacterial protection against toxic electrophilic compounds. Membranes 2023, 13, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozyamak, E.; Black, S.S.; Walker, C.A.; MacLean, M.J.; Bartlett, W.; Miller, S.; Booth, I.R. The critical role of S-lactoylglutathione formation during methylglyoxal detoxification in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 78, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, G.P.; Mclaggan, D.; Booth, L.R. Potassium channel activation by glutathione-S-conjugates in Escherichia coli: Protection against methylglyoxal is mediated by cytoplasmic acidification. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 17, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Fernández, E.Z.; Schuldiner, S. Acidification of cytoplasm in Escherichia coli provides a strategy to cope with stress and facilitates development of antibiotic resistance. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, K.P.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.; Min, B.; Park, C. Role of GldA in dihydroxyacetone and methylglyoxal metabolism of Escherichia coli K12. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 279, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, K.P.; Choi, D.; Kim, I.; Min, B.; Park, C. Hsp31 of Escherichia coli K-12 is glyoxalase III. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 81, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassier-Chauvat, C.; Marceau, F.; Farci, S.; Ouchane, S.; Chauvat, F. The glutathione system: A journey from Cyanobacteria to higher Eukaryotes. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorno, J. Glutathione! Integr. Med. 2014, 13, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kammerscheit, X.; Hecker, A.; Rouhier, N.; Chauvat, F.; Cassier-Chauvat, C. Methylglyoxal detoxification revisited: Role of glutathione transferase in model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. mBio 2020, 11, e00882-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirè, A.; Cianfruglia, L.; Minnelli, C.; Romaldi, B.; Laudadio, E.; Galeazzi, R.; Antognelli, C.; Armeni, T. Glyoxalase 2: Towards a broader view of the second player of the glyoxalase system. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.M.; Clugston, S.L.; Honek, J.F.; Matthews, B.W. Determination of the structure of Escherichia coli glyoxalase I suggests a structural basis for differential metal activation. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 8719–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozyamak, E.; De Almeida, C.; De Moura, A.P.S.; Miller, S.; Booth, I.R. Integrated stress response of Escherichia coli to methylglyoxal: Transcriptional readthrough from the nemRA operon enhances protection through increased expression of glyoxalase I. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 88, 936–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suttisansanee, U.; Honek, J.F. Bacterial glyoxalase enzymes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 22, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrangsu, P.; Dusi, R.; Hamilton, C.J.; Helmann, J.D. Methylglyoxal resistance in Bacillus subtilis: Contributions of bacillithiol-dependent and independent pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 91, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Shin, J.; Park, C. Novel regulatory system nemRA-gloA for electrophile reduction in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 88, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, C. Characterization of the Escherichia coli Yajl, YhbO and ElbB glyoxalases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnv239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skou, L.D.; Johansen, S.K.; Okarmus, J.; Meyer, M. Pathogenesis of DJ-1/PARK7-mediated Parkinson’s disease. Cells 2024, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujacic, M.; Bader, M.W.; Baneyx, F. Escherichia coli Hsp31 functions as a holding chaperone that cooperates with the DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE system in the management of protein misfolding under severe stress conditions. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujacic, M.; Baneyx, F. Chaperone Hsp31 contributes to acid resistance in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kthiri, F.; Le, H.T.; Gautier, V.R.; Caldas, T.; Malki, A.; Landoulsi, A.; Bohn, C.; Bouloc, P.; Richarme, G. Protein aggregation in a mutant deficient in YajL, the bacterial homolog of the parkinsonism-associated protein DJ-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 10328–10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.-T.; Gautier, V.; Kthiri, F.; Malki, A.; Messaoudi, N.; Mihoub, M.; Landoulsi, A.; An, Y.J.; Cha, S.-S.; Richarme, G. YajL, Prokaryotic homolog of parkinsonism-associated protein DJ-1, functions as a covalent chaperone for thiol proteome. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 5861–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.W.; Kool, E.T. Small substrate or large? Debate over the mechanism of glycation adduct repair by DJ-1. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Tak, S.; Jung, H.M.; Cha, S.; Hwang, E.; Lee, D.; Lee, J.H.; Ryu, K.S.; Park, C. Kinetic evidence in favor of glyoxalase III and against deglycase activity of DJ-1. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, A.; Bekkhozhin, Z.; Omertassova, N.; Baizhumanov, T.; Yeltay, G.; Akhmetali, M.; Toibazar, D.; Utepbergenov, D. The apparent deglycase activity of DJ-1 results from the conversion of free methylglyoxal present in fast equilibrium with hemithioacetals and hemiaminals. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 18863–18872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, M.C.; Shuck, S.C.; Lin, J.; Moxley, M.A.; Termini, J.; Cookson, M.R.; Wilson, M.A. DJ-1 is not a deglycase and makes a modest contribution to cellular defense against methylglyoxal damage in neurons. J. Neurochem. 2022, 162, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coukos, J.S.; Lee, C.W.; Pillai, K.S.; Shah, H.; Moellering, R.E. PARK7 catalyzes stereospecific detoxification of methylglyoxal consistent with glyoxalase and not deglycase function. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 3126–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, W.; Aoki, M.; Inoue, Y. Toxicity of dihydroxyacetone is exerted through the formation of methylglyoxal in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Effects on actin polarity and nuclear division. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 2637–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, I.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.L.; Min, B.; Park, C. Transcriptional activation of the aldehyde reductase YqhD by YqhC and its implication in glyoxal metabolism of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 4205–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Kim, I.; Yoo, S.; Min, B.; Kim, K.; Park, C. Conversion of methylglyoxal to acetol by Escherichia coli aldo-keto reductases. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 5782–5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Kim, I.; Park, C. Glyoxal detoxification in Escherichia coli K-12 by NADPH dependent aldo-keto reductases. J. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, K.K.; Miller, B.G. A metabolic bypass of the triosephosphate isomerase reaction. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 7983–7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Abudukadier, A.; Zhang, Q.; Li, P.; Xie, J. The Role of Methylglyoxal Detoxification in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Fitness and Pathogenesis. Microb Pathog 2025, 208, 107948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya-Sanchez, A.; Feng, Y.; Berude, J.C.; Portnoy, D.A. Detoxification of methylglyoxal by the glyoxalase system is required for glutathione availability and virulence activation in Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.S.; Joyce, L.R.; Spencer, B.L.; Brady, A.; McIver, K.S.; Doran, K.S. Identification of glyoxalase A in Group B Streptococcus and its contribution to methylglyoxal tolerance and virulence. Infect. Immun. 2025, 93, e0054024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, C.J.; Cuthbert, B.J.; Glanville, D.G.; Terrado, M.; Valverde Mendez, D.; Bratton, B.P.; Schemenauer, D.E.; Tokars, V.L.; Martin, T.G.; Rasmussen, L.W.; et al. A glyoxal-specific aldehyde signaling axis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa that influences quorum sensing and infection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiame, E.; Lamosa, P.; Santos, H.; Van Schaftingen, E. Identification of glucoselysine-6-phosphate deglycase, an enzyme involved in the metabolism of the fructation product glucoselysine. Biochem. J. 2005, 392, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, A.; Handzhiyski, Y.; Sredovska-Bozhinov, A.; Popova, E.; Odjakova, M.; Datsenko, K.A.; Wanner, B.L.; Ivanov, I.; Mironova, R. Substrate specificity of the Escherichia coli FRLB amadoriase. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2014, 26, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiame, E.; Delpierre, G.; Collard, F.; Van Schaftingen, E. Identification of a pathway for the utilization of the amadori product fructoselysine in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 42523–42529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Phillips, R.S.; Kilgore, P.B.; Smith, G.L.; Hoover, T.R. A mannose family phosphotransferase system permease and associated enzymes are required for utilization of fructoselysine and glucoselysine in Salmonella eeterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 2831–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boteva, E.; Doychev, K.; Kirilov, K.; Handzhiyski, Y.; Tsekovska, R.; Gatev, E.; Mironova, R. Deglycation activity of the Escherichia coli glycolytic enzyme phosphoglucose isomerase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Or, I.; Katz, C.; Ron, E.Z. Metabolism of AGEs-bacterial AGEs are degraded by metallo-proteases. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cohen-Or, I.; Katz, C.; Ron, E.Z. AGEs secreted by bacteria are involved in the inflammatory response. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Kaur, M.; Thompson, L.K.; Cox, G. A historical perspective on the multifunctional outer membrane channel protein TolC in Escherichia coli. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska, K.; Dzierzbicka, K.; Inkielewicz-Stȩpniak, I.; Przybyłowska, M. Therapeutic potential of carnosine and its derivatives in the treatment of human diseases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 1561–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D.; Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K.; Laskowska, E. Intracellular protective functions and therapeutic potential of trehalose. Molecules 2024, 29, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Klotzsche, M.; Werzinger, C.; Hegele, J.; Waibel, R.; Pischetsrieder, M. Reaction of folic acid with reducing sugars and sugar degradation products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1647–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jaseem, M.A.J.; Abdullah, K.M.; Qais, F.A.; Shamsi, A.; Naseem, I. Mechanistic insight into glycation inhibition of human serum albumin by vitamin B9: Multispectroscopic and molecular docking approach. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Di Pietro, L.; Cardaci, V.; Maugeri, S.; Caraci, F. The therapeutic potential of carnosine: Focus on cellular and molecular mechanisms. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2023, 4, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, C.; Hipkiss, A.R. Carnosine reacts with a glycated protein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, R.; Murray, D.B.; Metz, T.O.; Baynes, J.W. Chelation: A fundamental mechanism of action of AGE inhibitors, age breakers, and other inhibitors of diabetes complications. Diabetes 2012, 61, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chung, M.; Zhang, L.; Cai, S.; Pan, X.; Pan, Y. Targeting the AGEs-RAGE axis: Pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic interventions in diabetic wound healing. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1667620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakoso, N.M.; Sundari, A.M.; Fadhilah; Abinawanto; Pustimbara, A.; Dwiranti, A.; Bowolaksono, A. Methylglyoxal impairs human dermal fibroblast survival and migration by altering RAGE-hTERT mRNA expression in vitro. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 13, 101835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Fukami, K.; Elias, B.C.; Brooks, C.R. Dysbiosis-related advanced glycation endproducts and trimethylamine N-oxide in chronic kidney disease. Toxins 2021, 13, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinrimisi, O.I.; Maasen, K.; Scheijen, J.L.J.M.; Nemet, I.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Hanssen, N.M.J. Does gut microbial methylglyoxal metabolism impact human physiology? Antioxidants 2025, 14, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschner, M.; Skalny, A.; Gritsenko, V.; Kartashova, O.; Santamaria, A.; Rocha, J.; Spandidos, D.; Zaitseva, I.; Tsatsakis, A.; Tinkov, A. Role of gut microbiota in the modulation of the health effects of advanced glycation end-products (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2023, 51, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Yuan, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, J. Dietary advanced glycation end products modify gut microbial composition and partially increase colon permeability in rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiquer, I.; Rubio, L.A.; Peinado, M.J.; Delgado-Andrade, C.; Navarro, M.P. Maillard reaction products modulate gut microbiota composition in adolescents. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, A.; Ji, X.; Li, W.; Dong, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. The interaction between human microbes and advanced glycation end products: The role of Klebsiella X15 on advanced glycation end products’ degradation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong-Nguyen, K.; McNeill, B.A.; Aston-Mourney, K.; Rivera, L.R. Advanced Glycation End-Products and their effects on gut health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrocola, R.; Collotta, D.; Gaudioso, G.; Le Berre, M.; Cento, A.S.; Ferreira, G.A.; Chiazza, F.; Verta, R.; Bertocchi, I.; Manig, F.; et al. Effects of exogenous dietary advanced glycation end products on the cross-talk mechanisms linking microbiota to metabolic inflammation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.P.N.; Troise, A.D.; Fogliano, V.; De Vos, W.M. Anaerobic degradation of N-ϵ-carboxymethyllysine, a major glycation end-product, by human intestinal bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 6594–6602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corzo-Martínez, M.; Ávila, M.; Moreno, F.J.; Requena, T.; Villamiel, M. Effect of milk protein glycation and gastrointestinal digestion on the growth of Bifidobacteria and lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 2012, 153, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Jin, W.; Mao, Z.; Dong, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, B.; Wu, H.; Zeng, M. Microbiome and butyrate production are altered in the gut of rats fed a glycated fish protein diet. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 47, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, N.; Xue, M.; Thornalley, P.J. Dicarbonyls and glyoxalase in disease mechanisms and clinical therapeutics. Glycoconj. J. 2016, 33, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Wouters, K. Immunometabolism and the modulation of immune responses and host defense: A role for methylglyoxal? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Noeparvar, P.; Burne, R.A.; Glezer, B.S. Genetic characterization of glyoxalase pathway in oral Streptococci and its contribution to interbacterial competition. J. Oral Microbiol. 2024, 16, 2322241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.M.; Ong, C.Y.; Walker, M.J.; McEwan, A.G. Defence against methylglyoxal in group A Streptococcus: A role for glyoxylase I in bacterial virulence and survival in neutrophils? Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, ftv122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya-Sanchez, A.; Berry, S.B.; Espich, S.; Zilinskas, A.; Tran, P.M.; Agudelo, C.; Samani, H.; Darwin, K.H.; Portnoy, D.A.; Stanley, S.A. Methylglyoxal is an antibacterial effector produced by macrophages during infection. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Qaidi, S.; Scott, N.E.; Hardwidge, P.R. Arginine glycosylation enhances methylglyoxal detoxification. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günster, R.A.; Matthews, S.A.; Holden, D.W.; Thurston, T.L.M. SseK1 and SseK3 type III secretion system effectors inhibit NF-ΚB signaling and necroptotic cell death in Salmonella-infected macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00010-17, Erratum in Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00242-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Zhang, H.X.; Li, H.; Zhu, A.H.; Gao, W.Y. Measurement of α-dicarbonyl compounds in human saliva by pre-column derivatization HPLC. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2019, 57, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, M. Toxic AGEs (TAGE) Theory: A new concept for preventing the development of diseases related to lifestyle. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.J.; Cuthbert, B.J.; Garza-Sánchez, F.; Helou, C.C.; de Miranda, R.; Goulding, C.W.; Hayes, C.S. Advanced glycation end-product crosslinking activates a type VI Secretion system phospholipase effector protein. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, B.J.; Jensen, S.J.; Hayes, C.S.; Goulding, C.W. Advanced glycation end product (AGE) crosslinking of a bacterial protein: Are age-modifications going undetected in our studies? Struct. Dyn. 2025, 12, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, T.L. Dietary advanced glycation end-products elicit toxicological effects by disrupting gut microbiome and immune homeostasis. J. Immunotoxicol. 2021, 18, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirelli, E.; Pucci, M.; Squillario, M.; Bignotti, G.; Messali, S.; Zini, S.; Bugatti, M.; Cadei, M.; Memo, M.; Caruso, A.; et al. Effects of methylglyoxal on intestine and microbiome composition in aged mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 197, 115276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, C.K. Gastrointestinal motility and glycemic control in diabetes: The chicken and the egg revisited? J. Clin. Invest. 2006, 116, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D.; Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K.; Laskowska, E. Bacterial Adaptation to Stress Induced by Glyoxal/Methylglyoxal and Advanced Glycation End Products. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122778

Kuczyńska-Wiśnik D, Stojowska-Swędrzyńska K, Laskowska E. Bacterial Adaptation to Stress Induced by Glyoxal/Methylglyoxal and Advanced Glycation End Products. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122778

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuczyńska-Wiśnik, Dorota, Karolina Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, and Ewa Laskowska. 2025. "Bacterial Adaptation to Stress Induced by Glyoxal/Methylglyoxal and Advanced Glycation End Products" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122778

APA StyleKuczyńska-Wiśnik, D., Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K., & Laskowska, E. (2025). Bacterial Adaptation to Stress Induced by Glyoxal/Methylglyoxal and Advanced Glycation End Products. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122778