Comparison of Gut Microbiome Profile of Chickens Infected with Three Eimeria Species Reveals New Insights on Pathogenicity of Avian Coccidia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chickens and Parasites

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. DNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

2.4. Bioinformatics and Data Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Pathological Findings

3.2. Jejunum and Cecum 16S rRNA Sequences

3.3. Shared and Unique Core Microbial Populations

3.4. Alpha and Beta Diversity of Jejunal and Cecal Microbial Constitution After E. tenella, E. maxima and E. necatrix Infection

3.5. Bacterial Taxa in the Jejunum and Cecum After E. tenella, E. maxima and E. necatrix Infection

3.5.1. At the Phylum Level

3.5.2. At the Genus Level

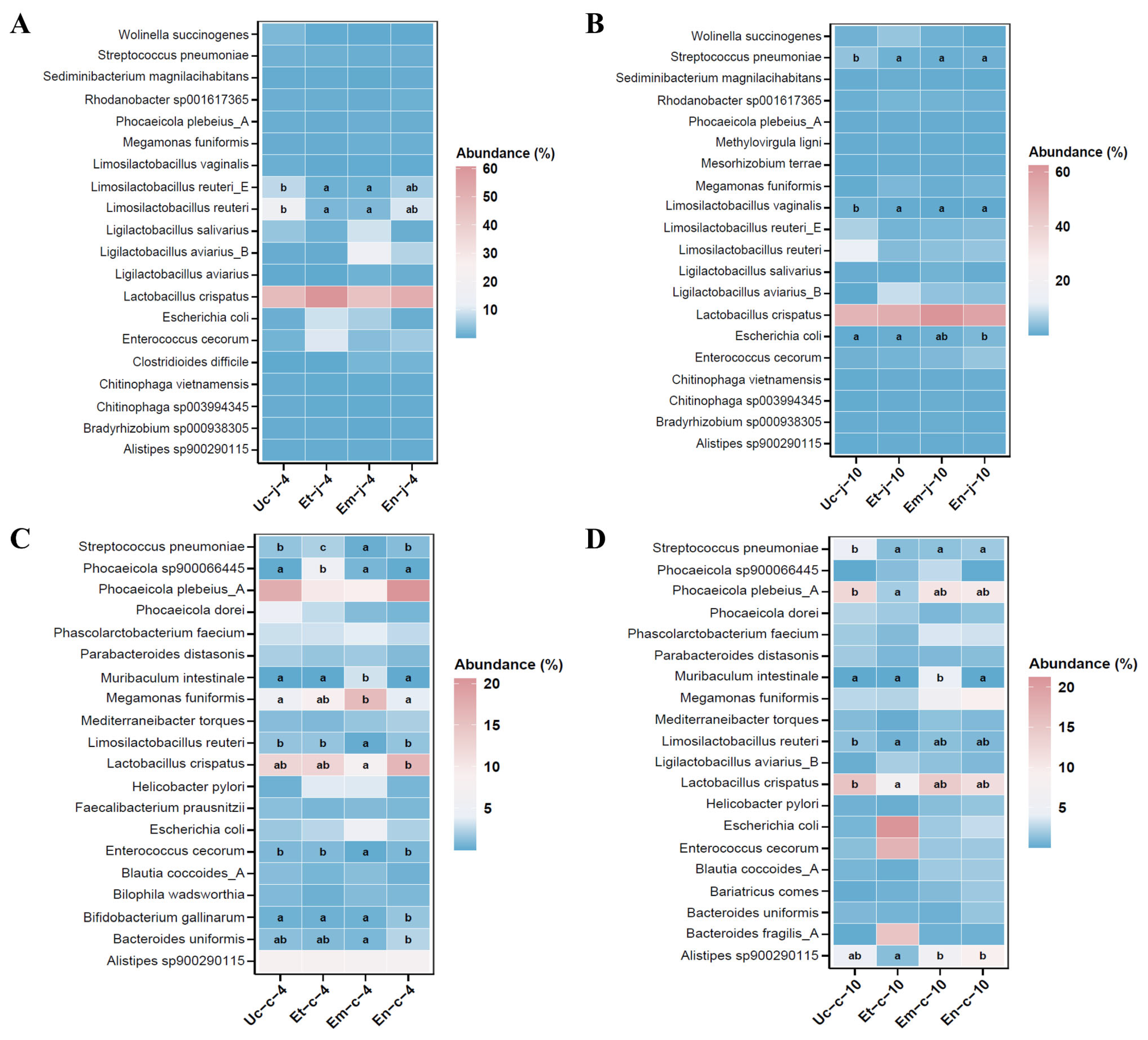

3.5.3. At the Species Level

3.6. LEfSe Analysis of Differences in the Microbiota of the Jejunum and Cecum After E. tenella, E. maxima and E. necatrix Infection

3.7. Functional Prediction of Microbiota

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blake, D.P.; Knox, J.; Dehaeck, B.; Huntington, B.; Rathinam, T.; Ravipati, V.; Ayoade, S.; Gilbert, W.; Adebambo, A.O.; Jatau, I.D.; et al. Re-calculating the cost of coccidiosis in chickens. Vet. Res. 2020, 51, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Lu, M.; Lillehoj, H.S. Coccidiosis: Recent Progress in Host Immunity and Alternatives to Antibiotic Strategies. Vaccines 2022, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, H.W.; Landman, W.J.M. Coccidiosis in poultry: Anticoccidial products, vaccines and other prevention strategies. Vet. Q. 2011, 31, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Kumar, S.; Oakley, B.; Kim, W.K. Chicken Gut Microbiota: Importance and Detection Technology. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D.; Hughes, R.J.; Moore, R.J. Microbiota of the chicken gastrointestinal tract: Influence on health, productivity and disease. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 4301–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo, V.; Flórez, M.J.V. The gastrointestinal microbiome and its association with the control of pathogens in broiler chicken production: A review. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Tang, X.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Suo, J.; Jia, Y.; El-Ashram, S.; et al. Influence of Eimeria falciformis Infection on Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Pathways in Mice. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlala, T.; Okpeku, M.; Adeleke, M.A. Understanding the interactions between Eimeria infection and gut microbiota, towards the control of chicken coccidiosis: A review. Parasite 2021, 28, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonissen, G.; Eeckhaut, V.; Van Driessche, K.; Onrust, L.; Haesebrouck, F.; Ducatelle, R.; Moore, R.J.; Van Immerseel, F. Microbial shifts associated with necrotic enteritis. Avian Pathol. J. WVPA 2016, 45, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, R. Interactions Between Parasites and the Bacterial Microbiota of Chickens. Avian Dis. 2017, 61, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S.E.; van Diemen, P.M.; Martineau, H.; Stevens, M.P.; Tomley, F.M.; Stabler, R.A.; Blake, D.P. Impact of Eimeria tenella Coinfection on Campylobacter jejuni Colonization of the Chicken. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00772-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadde, U.; Kim, W.H.; Oh, S.T.; Lillehoj, H.S. Alternatives to antibiotics for maximizing growth performance and feed efficiency in poultry: A review. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2017, 18, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-L.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Zhao, G.-X.; Huang, H.-B.; Li, H.-R.; Shi, C.-W.; Yang, W.-T.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Wang, J.-Z.; Ye, L.-P.; et al. Dissection of the cecal microbial community in chickens after Eimeria tenella infection. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, P.; Zhang, K.; Bai, S.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Q.; Peng, H.; Mu, Y.; Xuan, Y.; et al. Probiotic Bacillus subtilis QST713 improved growth performance and enhanced the intestinal health of yellow-feather broilers challenged with coccidia and Clostridium perfringens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Gao, Y.; Xu, L.; Yan, R.; Li, X. Partial protection against four species of chicken coccidia induced by multivalent subunit vaccine. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, L.H.; Sun, B.B.; Zuo, B.X.Z.; Chen, X.Q.; Du, A.F. Prevalence and drug resistance of avian Eimeria species in broiler chicken farms of Zhejiang province, China. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 2104–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengat Prakashbabu, B.; Thenmozhi, V.; Limon, G.; Kundu, K.; Kumar, S.; Garg, R.; Clark, E.; Rao, A.S.; Raj, D.; Raman, M.; et al. Eimeria species occurrence varies between geographic regions and poultry production systems and may influence parasite genetic diversity. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 233, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.E.; Hesketh, P. Immunity to coccidiosis: Stages of the life-cycle of Eimeria maxima which induce, and are affected by, the response of the host. Parasitology 1976, 73, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougald, L.R.; Cervantes, H.M.; Jenkins, M.C.; Hess, M.; Beckstead, R. Protozoal Infections. In Diseases of Poultry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1192–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Tang, X.; Bi, F.; Hao, Z.; Han, Z.; Suo, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Duan, C.; Yu, Z.; et al. Eimeria tenella infection perturbs the chicken gut microbiota from the onset of oocyst shedding. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 258, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, V.; Shirley, M.W. The endogenous development of virulent strains and attenuated precocious lines of Eimeria tenella and E. necatrix. J. Parasitol. 1987, 73, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.H.; Jia, L.S.; Wei, S.S.; Ding, H.Y.; Yang, J.Y.; Wang, H.W. Effects of Eimeria tenella infection on the barrier damage and microbiota diversity of chicken cecum. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Kim, W. Interactions of Microbiota and Mucosal Immunity in the Ceca of Broiler Chickens Infected with Eimeria tenella. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Li, R.W.; Zhao, H.; Yan, X.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Sun, Z.; Oh, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Effects of Eimeria maxima and Clostridium perfringens infections on cecal microbial composition and the possible correlation with body weight gain in broiler chickens. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 132, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Suding, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, D.; Su, S.; Xu, J.; Hu, J.; Tao, J. Full-length transcriptome analysis and identification of transcript structures in Eimeria necatrix from different developmental stages by single-molecule real-time sequencing. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Wang, F.; Cao, L.; Wang, L.; Su, S.; Hou, Z.; Xu, J.; Hu, J.; Tao, J. Identification and characterization of a cDNA encoding a gametocyte-specific protein of the avian coccidial parasite Eimeria necatrix. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2020, 240, 111318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Wang, F.; Liu, D.; Su, S.; Xu, J.; Hu, J.; Tao, J. Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing revealed an altered microbiome diversity and composition of the jejunum and cecum in chicken infected with Eimeria necatrix. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 336, 110458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaingu, F.; Liu, D.; Wang, L.; Tao, J.; Waihenya, R.; Kutima, H. Anticoccidial effects of Aloe secundiflora leaf extract against Eimeria tenella in broiler chicken. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2017, 49, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cao, L.; Zhu, Y.; Deng, C.; Su, S.; Xu, J.; Jin, W.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; Tao, J. Cloning and characterization of an Eimeria necatrix gene encoding a gametocyte protein and associated with oocyst wall formation. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, J.; Cao, L.; Wang, S.; Han, H.; Wu, Y.; Tao, J. Analysis of differentially expressed genes in two immunologically distinct strains of Eimeria maxima using suppression subtractive hybridization and dot-blot hybridization. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan Community Ecology Package. Version 2.6-2. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Lozupone, C.; Lladser, M.E.; Knights, D.; Stombaugh, J.; Knight, R. UniFrac: An effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J. 2011, 5, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langille, M.G.I.; Zaneveld, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; McDonald, D.; Knights, D.; Reyes, J.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Vega Thurber, R.L.; Knight, R.; et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittoe, D.K.; Olson, E.G.; Ricke, S.C. Impact of the gastrointestinal microbiome and fermentation metabolites on broiler performance. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ncho, C.M. Heat stress and the chicken gastrointestinal microbiota: A systematic review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Pineda, C.; Navarro-Ruíz, J.L.; López-Osorio, S.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J.J.; Gómez-Osorio, L.M. Chicken Coccidiosis: From the Parasite Lifecycle to Control of the Disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 787653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, G.F.; Lumpkins, B.; Cervantes, H.M.; Fitz-Coy, S.H.; Jenkins, M.C.; Jones, M.K.; Price, K.R.; Dalloul, R.A. Coccidiosis in poultry: Disease mechanisms, control strategies, and future directions. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Hu, J.; Peng, H.; Li, B.; Xu, J.; Song, X.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Du, X.; Bu, G.; et al. Research Note: The gut microbiota varies with dietary fiber levels in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindari, Y.R.; Gerber, P.F. Centennial Review: Factors affecting the chicken gastrointestinal microbial composition and their association with gut health and productive performance. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, P.B.; Godoy-Santos, F.; Lawther, K.; Richmond, A.; Corcionivoschi, N.; Huws, S.A. Decoding the chicken gastrointestinal microbiome. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chica Cardenas, L.A.; Clavijo, V.; Vives, M.; Reyes, A. Bacterial meta-analysis of chicken cecal microbiota. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, H.M. Bacteroides: The good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Ju, T.; Bhardwaj, T.; Korver, D.R.; Willing, B.P. Week-Old Chicks with High Bacteroides Abundance Have Increased Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Reduced Markers of Gut Inflammation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0361622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamieva, Z.; Poluektova, E.; Svistushkin, V.; Sobolev, V.; Shifrin, O.; Guarner, F.; Ivashkin, V. Antibiotics, gut microbiota, and irritable bowel syndrome: What are the relations? World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 1204–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzatti, G.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Gibiino, G.; Binda, C.; Gasbarrini, A. Proteobacteria: A Common Factor in Human Diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9351507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Niu, S.; Tie, K.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, H.; Gao, C.; Yu, T.; Lei, L.; Feng, X. Characteristics of the intestinal flora of specific pathogen free chickens with age. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 132, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Song, Z.; Cen, Y.; Fan, J.; Li, P.; Si, H.; Hu, D. Susceptibility and cecal microbiota alteration to Eimeria-infection in Yellow-feathered broilers, Arbor Acres broilers and Lohmann pink layers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Wei, P.; Liao, H.Y.; Tsai, Y.W.; Cheng, M.C.; Lien, Y.Y. Comprehensive analysis of Eimeria necatrix infection: From intestinal lesions to gut microbiota and metabolic disturbances. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, J.; Whitmore, M.A.; Tobin, I.; Kim, D.M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, G. Dynamic response of the intestinal microbiome to Eimeria maxima-induced coccidiosis in chickens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0082324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Covington, A.; Pamer, E.G. The intestinal microbiota: Antibiotics, colonization resistance, and enteric pathogens. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 279, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, S.E.; Nolan, M.J.; Harman, K.; Boulton, K.; Hume, D.A.; Tomley, F.M.; Stabler, R.A.; Blake, D.P. Effects of Eimeria tenella infection on chicken caecal microbiome diversity, exploring variation associated with severity of pathology. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Nie, K.; Huang, Q.; Li, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, R.; Wang, Z.; Hu, S. Changes of cecal microflora in chickens following Eimeria tenella challenge and regulating effect of coated sodium butyrate. Exp. Parasitol. 2017, 177, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebessa, E.; Guo, L.; Chen, X.; Bello, S.F.; Cai, B.; Girma, M.; Hanotte, O.; Nie, Q. Influence of Eimeria maxima coccidia infection on gut microbiome diversity and composition of the jejunum and cecum of indigenous chicken. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 994224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Q.; Tang, J.; Dong, L.; Dai, G.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, G.; Xie, K.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Z. Comprehensive analysis of gut microbiome and host transcriptome in chickens after Eimeria tenella infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1191939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Cheng, C.C.; Zheng, J.; Liu, J.; Quevedo, R.M.; Li, J.; Roos, S.; Gänzle, M.G.; Walter, J. Limosilactobacillus balticus sp. nov., Limosilactobacillus agrestis sp. nov., Limosilactobacillus albertensis sp. nov., Limosilactobacillus rudii sp. nov. and Limosilactobacillus fastidiosus sp. nov., five novel Limosilactobacillus species isolated from the vertebrate gastrointestinal tract, and proposal of six subspecies of Limosilactobacillus reuteri adapted to the gastrointestinal tract of specific vertebrate hosts. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 004644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nii, T.; Kakuya, H.; Isobe, N.; Yoshimura, Y. Lactobacillus reuteri Enhances the Mucosal Barrier Function Against Heat-killed Salmonella Typhimurium in the Intestine of Broiler Chicks. J. Poult. Sci. 2020, 57, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Guo, Y.; Mohamed, T.; Bumbie, G.Z.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Zhao, J.; Du, H.; Tang, Z.; Xu, Y.; et al. Dietary Lactobacillus reuteri SL001 Improves Growth Performance, Health-Related Parameters, Intestinal Morphology and Microbiota of Broiler Chickens. Animals 2023, 13, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Hu, X.; Mi, J.; Hu, H.; Wang, H.; Qi, X.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Ligilactobacillus salivarius XP132 with antibacterial and immunomodulatory activities inhibits horizontal and vertical transmission of Salmonella Pullorum in chickens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eeckhaut, V.; Van Immerseel, F.; Croubels, S.; De Baere, S.; Haesebrouck, F.; Ducatelle, R.; Louis, P.; Vandamme, P. Butyrate production in phylogenetically diverse Firmicutes isolated from the chicken caecum. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yue, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, J. The safety and potential probiotic properties analysis of Streptococcus alactolyticus strain FGM isolated from the chicken cecum. Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 19, Erratum in Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 39.. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, J.; Silva, V.; Monteiro, A.; Vieira-Pinto, M.; Igrejas, G.; Reis, F.S.; Barros, L.; Poeta, P. Antibiotic Resistance among Gastrointestinal Bacteria in Broilers: A Review Focused on Enterococcus spp. and Escherichia coli. Animals 2023, 13, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.M.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria with Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralova, S.; Davidova-Gerzova, L.; Valcek, A.; Bezdicek, M.; Rychlik, I.; Rezacova, V.; Cizek, A. Paraphocaeicola brunensis gen. nov., sp. nov., Carrying Two Variants of nimB Resistance Gene from Bacteroides fragilis, and Caecibacteroides pullorum gen. nov., sp. nov., Two Novel Genera Isolated from Chicken Caeca. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0195421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, A.G.; Goodman, A.L. An insider’s perspective: Bacteroides as a window into the microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, Q.; Chen, K. Gut microbial composition is altered in sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marcantonio, L.; Marotta, F.; Vulpiani, M.P.; Sonntag, Q.; Iannetti, L.; Janowicz, A.; Di Serafino, G.; Di Giannatale, E.; Garofolo, G. Investigating the cecal microbiota in broiler poultry farms and its potential relationships with animal welfare. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 144, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Wang, X.; Qi, X.; Cao, C.; Yang, K.; Gu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, Q. Identification of the gut microbiota affecting Salmonella pullorum and their relationship with reproductive performance in hens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1216542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Cui, T.; Qin, S.; Wang, T.; Liu, J.; Sa, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, C. Beneficial effects of Lactobacillus plantarum on growth performance, immune status, antioxidant function and intestinal microbiota in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Bai, H.; Mo, W.; Zheng, X.; Chen, H.; Yin, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Shi, Q.; Zuo, Z.; et al. Lactic Acid Bacteria Bacteriocins: Safe and Effective Antimicrobial Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.H.; Rodriguez Jimenez, D.M.; Meisel, M. Limosilactobacillus reuteri—A probiotic gut commensal with contextual impact on immunity. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2451088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Shaufi, M.A.; Sieo, C.C.; Chong, C.W.; Gan, H.M.; Ho, Y.W. Deciphering chicken gut microbial dynamics based on high-throughput 16S rRNA metagenomics analyses. Gut Pathog. 2015, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Doherty, M.; Yang, T.; Li, J.; Weng, Q.; Wei, J.; Zeng, C.; et al. Gut Fungal Dysbiosis and Altered Fungi-Bacteria Correlation Network Were Associated with Knee Synovitis in a Middle-Aged and Older General Population in China. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, S361–S362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morotomi, M.; Nagai, F.; Watanabe, Y. Description of Christensenella minuta gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from human faeces, which forms a distinct branch in the order Clostridiales, and proposal of Christensenellaceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatyeva, O.; Tolyneva, D.; Kovalyov, A.; Matkava, L.; Terekhov, M.; Kashtanova, D.; Zagainova, A.; Ivanov, M.; Yudin, V.; Makarov, V.; et al. Christensenella minuta, a new candidate next-generation probiotic: Current evidence and future trajectories. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1241259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassab, N.S.; Alsammarraie, N.; Sarsam, T.; Al-Sammarraie, M.; Watt, J. A Rare Case of Gemella haemolysans Endocarditis: A Challenging Diagnosis. Cureus 2024, 16, e52030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, G.; Mishra, B.; Sahoo, S.; Mahapatra, A. Granulicatella adiacens as an Unusual Cause of Empyema: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Lab. Physicians 2022, 14, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodaka, S.; Uchida, T.; Gomi, H. Gemella haemolysans as an emerging pathogen for bacteremia among the elderly. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2022, 23, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.K.; Jiang, T.; Al-Rubaye, A.A.; Rhoads, D.D.; Wideman, R.F.; Zhao, J.; Pevzner, I.; Kwon, Y.M. An investigation into blood microbiota and its potential association with Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO) in Broilers. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, K.N.; Blanchard, J.L. Reclassification of the Clostridium clostridioforme and Clostridium sphenoides clades as Enterocloster gen. nov. and Lacrimispora gen. nov., including reclassification of 15 taxa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresford-Jones, B.S.; Suyama, S.; Clare, S.; Soderholm, A.; Xia, W.; Sardar, P.; Lee, J.; Harcourt, K.; Lawley, T.D.; Pedicord, V.A. Enterocloster clostridioformis protects against Salmonella pathogenesis and modulates epithelial and mucosal immune function. Microbiome 2025, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobo, F.; Rodríguez-Granger, J.; Navarro-Mari, J.M.; Ceballos-Atienza, R.; Sampedro-Martínez, A.; Reguera-Márquez, J.A. Four cases of bacteremia caused by Enterocloster clostridioformis. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. Publ. Of. Soc. Esp. Quimioter. 2025, 38, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrieu, C.; Mailhe, M.; Ricaboni, D.; Fonkou, M.D.M.; Bilen, M.; Cadoret, F.; Tomei, E.; Armstrong, N.; Vitton, V.; Benezech, A.; et al. Noncontiguous finished genome sequences and description of Bacteroides mediterraneensis sp. nov., Bacteroides ihuae sp. nov., Bacteroides togonis sp. nov., Bacteroides ndongoniae sp. nov., Bacteroides ilei sp. nov. and Bacteroides Congonensis sp. nov. Identified by culturomics. New Microbes New Infect. 2018, 26, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Lan, P.T.N.; Benno, Y. Barnesiella viscericola gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the family Porphyromonadaceae isolated from chicken caecum. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Fernández, S.; Cretenet, M.; Bernardeau, M. In vitro inhibition of avian pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum isolates by probiotic Bacillus strains. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 2338–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.; Lee, Y. Clinical Outcomes and Molecular Characteristics of Bacteroides fragilis Infections. Ann. Lab. Med. 2025, 45, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, D.M. Inhibition of Clostridium perfringens sporulation by Bacteroides fragilis and short-chain fatty acids. Anaerobe 2004, 10, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Zhu, W.; Su, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, T. Multi-Omics Analysis After Vaginal Administration of Bacteroides fragilis in Chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 846011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; You, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, X.; He, X.; Liu, J.; Ma, N. Improving fatty liver hemorrhagic syndrome in laying hens through gut microbiota and oxylipin metabolism by Bacteroides fragilis: A potential involvement of arachidonic acid. Anim. Nutr. (Zhongguo Xu Mu Shou Yi Xue Hui) 2025, 20, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H. Role of Flagella in the Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori. Curr. Microbiol. 2017, 74, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, M.; Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E.; Moussa, I.M.; Hessain, A.M.; Alhaji, J.H.; Heme, H.A.; Zahran, R.; Abdeen, E. Helicobacter pylori in a poultry slaughterhouse: Prevalence, genotyping and antibiotic resistance pattern. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorob’ev, A.V.; de Boer, W.; Folman, L.B.; Bodelier, P.L.E.; Doronina, N.V.; Suzina, N.E.; Trotsenko, Y.A.; Dedysh, S.N. Methylovirgula ligni gen. nov., sp. nov., an obligately acidophilic, facultatively methylotrophic bacterium with a highly divergent mxaF gene. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 2538–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehne, S.A.; Cartman, S.T.; Heap, J.T.; Kelly, M.L.; Cockayne, A.; Minton, N.P. The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection. Nature 2010, 467, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Treviño, D.; Flores-Treviño, S.; Cisneros-Rendón, C.; Domínguez-Rivera, C.V.; Camacho-Ortiz, A. Co-Colonization of Non-difficile Clostridial Species in Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea Caused by Clostridioides difficile. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weese, J.S. Clostridium (Clostridioides) difficile in animals. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2020, 32, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, H.; Pigneur, B.; Watterlot, L.; Lakhdari, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Gratadoux, J.-J.; Blugeon, S.; Bridonneau, C.; Furet, J.-P.; Corthier, G.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16731–16736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, M.; Martín, R.; Torres-Maravilla, E.; Chadi, S.; González-Dávila, P.; Sokol, H.; Langella, P.; Chain, F.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G. Butyrate mediates anti-inflammatory effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in intestinal epithelial cells through Dact3. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkuna, S.; Ghimire, S.; Chankhamhaengdecha, S.; Janvilisri, T.; Scaria, J. Mediterraneibacter catenae SW178 sp. nov., an intestinal bacterium of feral chicken. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, J.S.; Ticer, T.D.; Engevik, M.A. Characterizing the mucin-degrading capacity of the human gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, M.; Feng, J. Gut microbiota dysbiosis exaggerates ammonia-induced tracheal injury Via TLR4 signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 246, 114206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, S.; Shin, Y.H.; Ma, X.; Park, S.M.; Graham, D.B.; Xavier, R.J.; Clardy, J. A Cardiolipin from Muribaculum intestinale Induces Antigen-Specific Cytokine Responses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 23422–23426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Kang, S.; Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; et al. Muribaculum intestinale restricts Salmonella Typhimurium colonization by converting succinate to propionate. ISME J. 2025, 19, wraf069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-García, R.; López-Almela, I.; Olivares, M.; Romaní-Pérez, M.; Manghi, P.; Torres-Mayo, A.; Tolosa-Enguís, V.; Flor-Duro, A.; Bullich-Vilarrubias, C.; Rubio, T.; et al. Gut commensal Phascolarctobacterium faecium retunes innate immunity to mitigate obesity and metabolic disease in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, M.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Tindall, B.J.; Gronow, S.; Woyke, T.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Hahnke, R.L.; Göker, M. Analysis of 1000 Type-Strain Genomes Improves Taxonomic Classification of Bacteroidetes. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Hu, P.Y.; Chen, C.S.; Lin, W.H.; Hsu, D.K.; Liu, F.T.; Meng, T.-C. Gut colonization of Bacteroides plebeius suppresses colitis-associated colon cancer development. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0259924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiam, M.; Wang, Q.; Barreto Sánchez, A.L.; Zhang, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Heterophil/Lymphocyte Ratio Level Modulates Salmonella Resistance, Cecal Microbiota Composition and Functional Capacity in Infected Chicken. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 816689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanom, H.; Nath, C.; Mshelbwala, P.P.; Pasha, M.R.; Magalhaes, R.S.; Alawneh, J.I.; Hassan, M.M. Epidemiology and molecular characterisation of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from chicken meat. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzerova, J.; Zeman, M.; Babak, V.; Jureckova, K.; Nykrynova, M.; Varga, M.; Weckwerth, W.; Dolejska, M.; Provaznik, V.; Rychlik, I.; et al. Detecting horizontal gene transfer among microbiota: An innovative pipeline for identifying co-shared genes within the mobilome through advanced comparative analysis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0196423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Park, J.E.; Lee, K.C.; Eom, M.K.; Oh, B.S.; Yu, S.Y.; Kang, S.W.; Han, K.-I.; Suh, M.K.; et al. Anaerotignum faecicola sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. J. Microbiol. 2019, 57, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, A.; Goto, K.; Ohtaki, Y.; Kaku, N.; Ueki, K. Description of Anaerotignum aminivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., a strictly anaerobic, amino-acid-decomposing bacterium isolated from a methanogenic reactor, and reclassification of Clostridium propionicum, Clostridium neopropionicum and Clostridium lactatifermentans as species of the genus Anaerotignum. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 4146–4153. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Deng, N.; Peng, X.; Tan, Z. Diarrhea with deficiency kidney-yang syndrome caused by adenine combined with Folium senna was associated with gut mucosal microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1007609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petzoldt, D.; Breves, G.; Rautenschlein, S.; Taras, D. Harryflintia acetispora gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from chicken caecum. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4099–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drent, W.J.; Lahpor, G.A.; Wiegant, W.M.; Gottschal, J.C. Fermentation of Inulin by Clostridium thermosuccinogenes sp. nov., a Thermophilic Anaerobic Bacterium Isolated from Various Habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koendjbiharie, J.G.; Wiersma, K.; van Kranenburg, R. Investigating the Central Metabolism of Clostridium thermosuccinogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00363-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailhe, M.; Ricaboni, D.; Benezech, A.; Lagier, J.C.; Fournier, P.E.; Raoult, D. ‘Tidjanibacter massiliensis’ gen. nov., sp. nov., a new bacterial species isolated from human colon. New Microbes New Infect. 2017, 17, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, L.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Cai, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens D1 Soy Milk Supplementation on Serum Biochemical Indexes and Intestinal Health of Bearded Chickens. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, L.; Su, D.; Liu, D.; Xu, J.; Tao, J. Combined serum lipid levels and lipidomic analysis reveals effects of Eimeria maxima and Eimeria tenella infection on lipid metabolism in chicken. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 337, 110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, N.; Liu, D.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Wang, F.; Su, S.; Xu, J.; Tao, J. Comparison of Gut Microbiome Profile of Chickens Infected with Three Eimeria Species Reveals New Insights on Pathogenicity of Avian Coccidia. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2752. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122752

Xue N, Liu D, Feng Q, Zhu Y, Cheng C, Wang F, Su S, Xu J, Tao J. Comparison of Gut Microbiome Profile of Chickens Infected with Three Eimeria Species Reveals New Insights on Pathogenicity of Avian Coccidia. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2752. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122752

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Nianyu, Dandan Liu, Qianqian Feng, Yu Zhu, Cheng Cheng, Feiyan Wang, Shijie Su, Jinjun Xu, and Jianping Tao. 2025. "Comparison of Gut Microbiome Profile of Chickens Infected with Three Eimeria Species Reveals New Insights on Pathogenicity of Avian Coccidia" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2752. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122752

APA StyleXue, N., Liu, D., Feng, Q., Zhu, Y., Cheng, C., Wang, F., Su, S., Xu, J., & Tao, J. (2025). Comparison of Gut Microbiome Profile of Chickens Infected with Three Eimeria Species Reveals New Insights on Pathogenicity of Avian Coccidia. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2752. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122752