Study on the Source and Microbial Mechanisms Influencing Heavy Metals and Nutrients in a Subtropical Deep-Water Reservoir

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

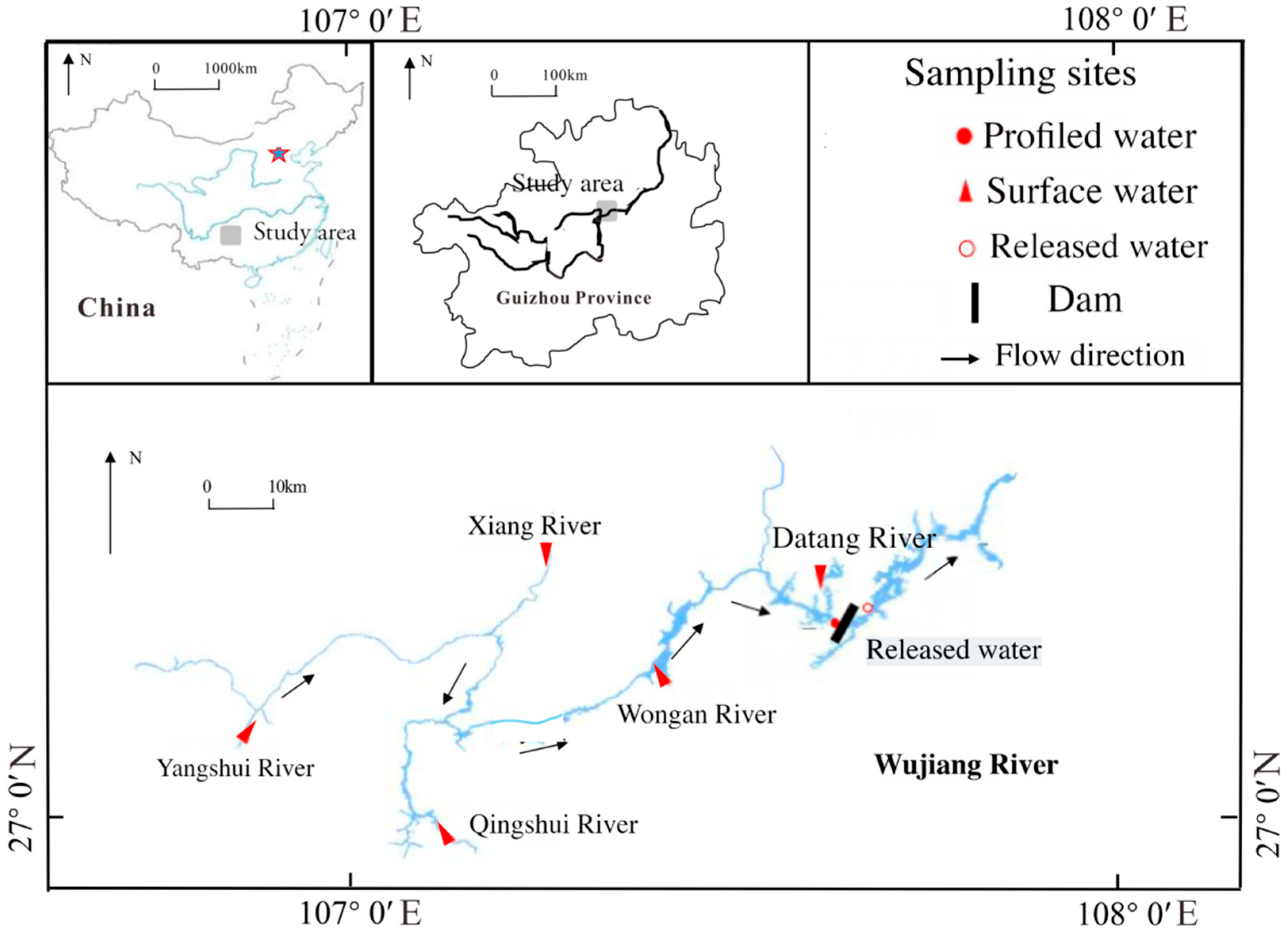

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Analyzing and Sampling

3. Results

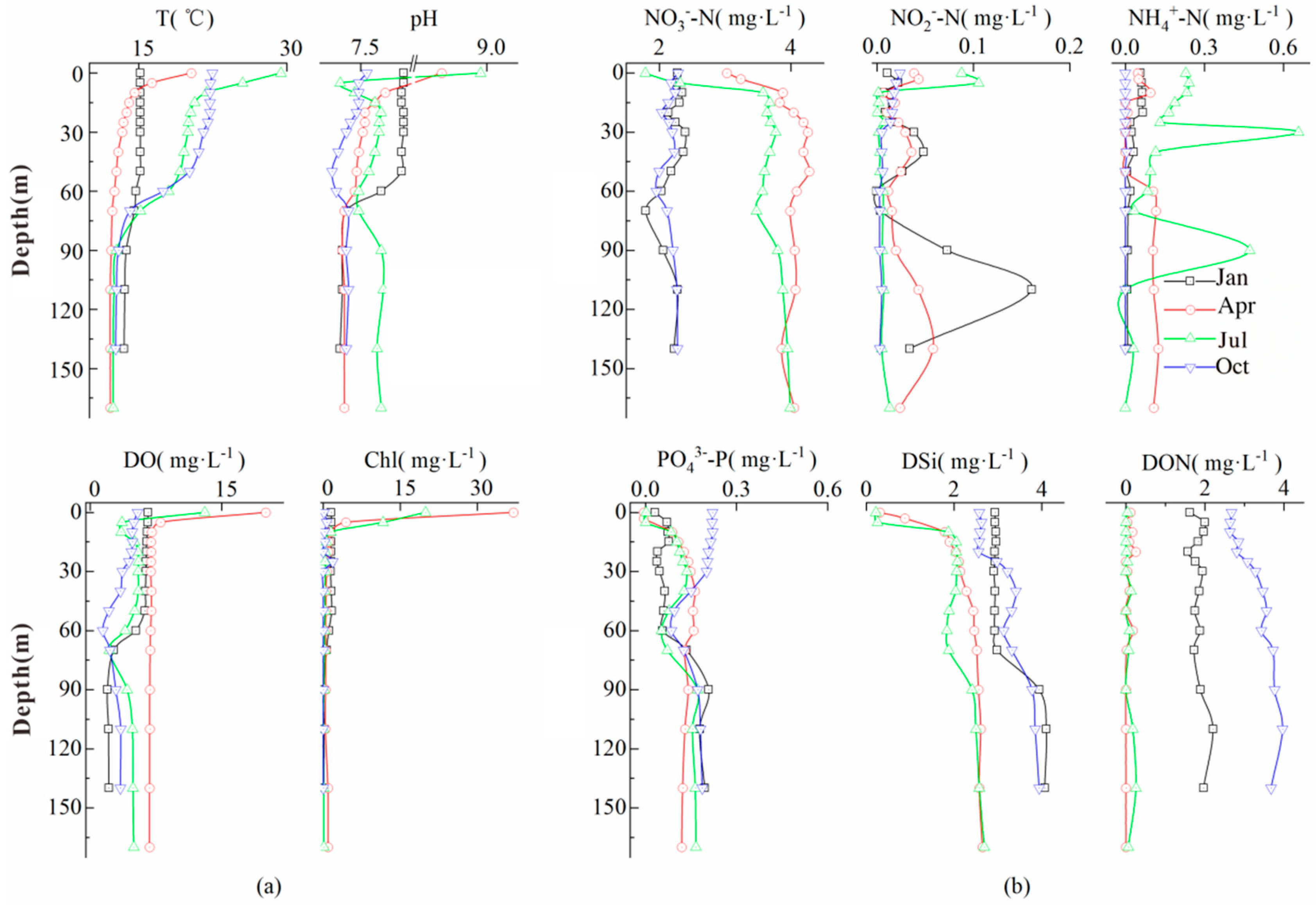

3.1. Physicochemical Properties and Chlorophyll A

3.2. Temporal and Spatial Variations in Water Nutrients

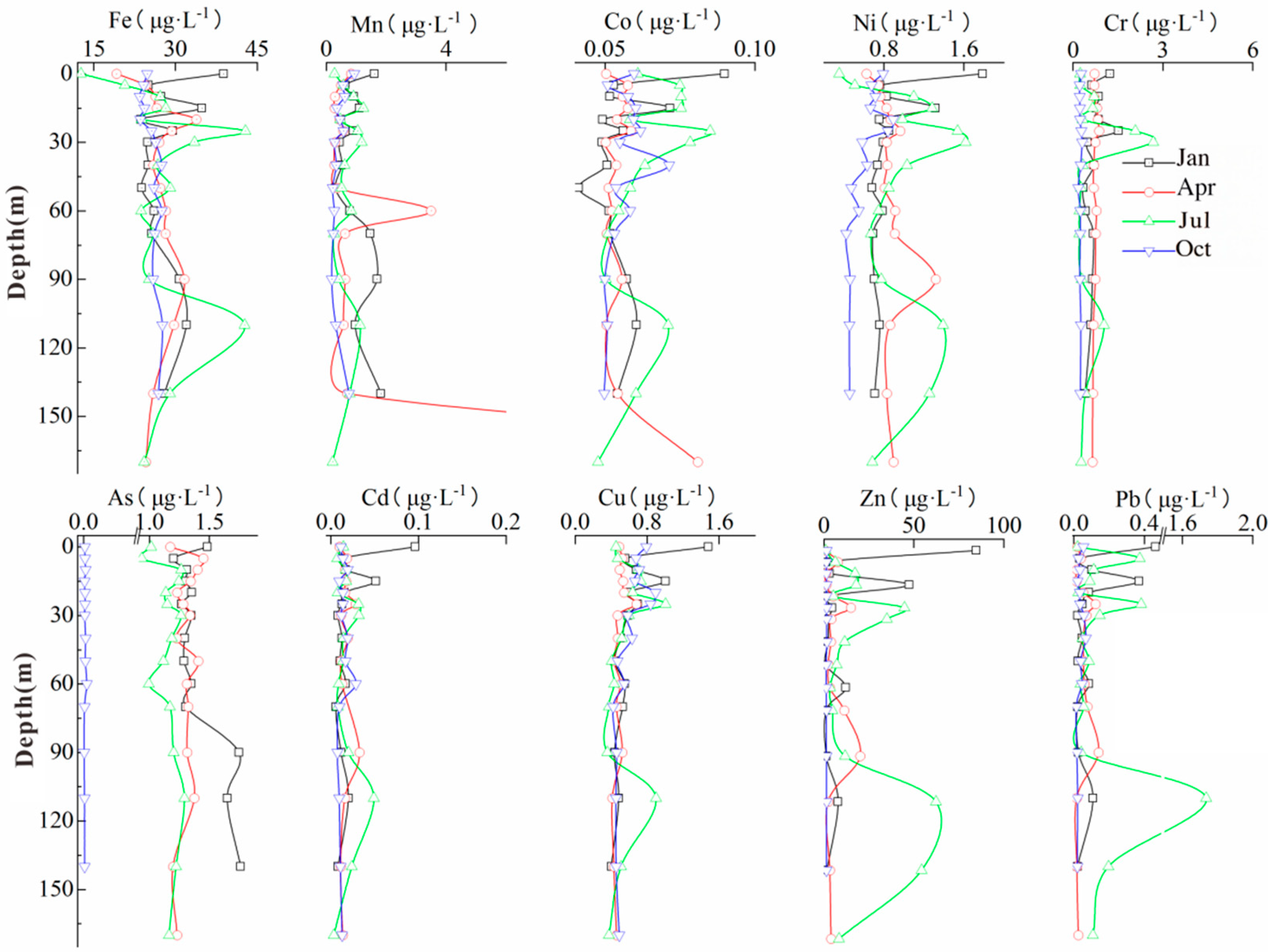

3.3. Temporal and Spatial Variations in Heavy Metals

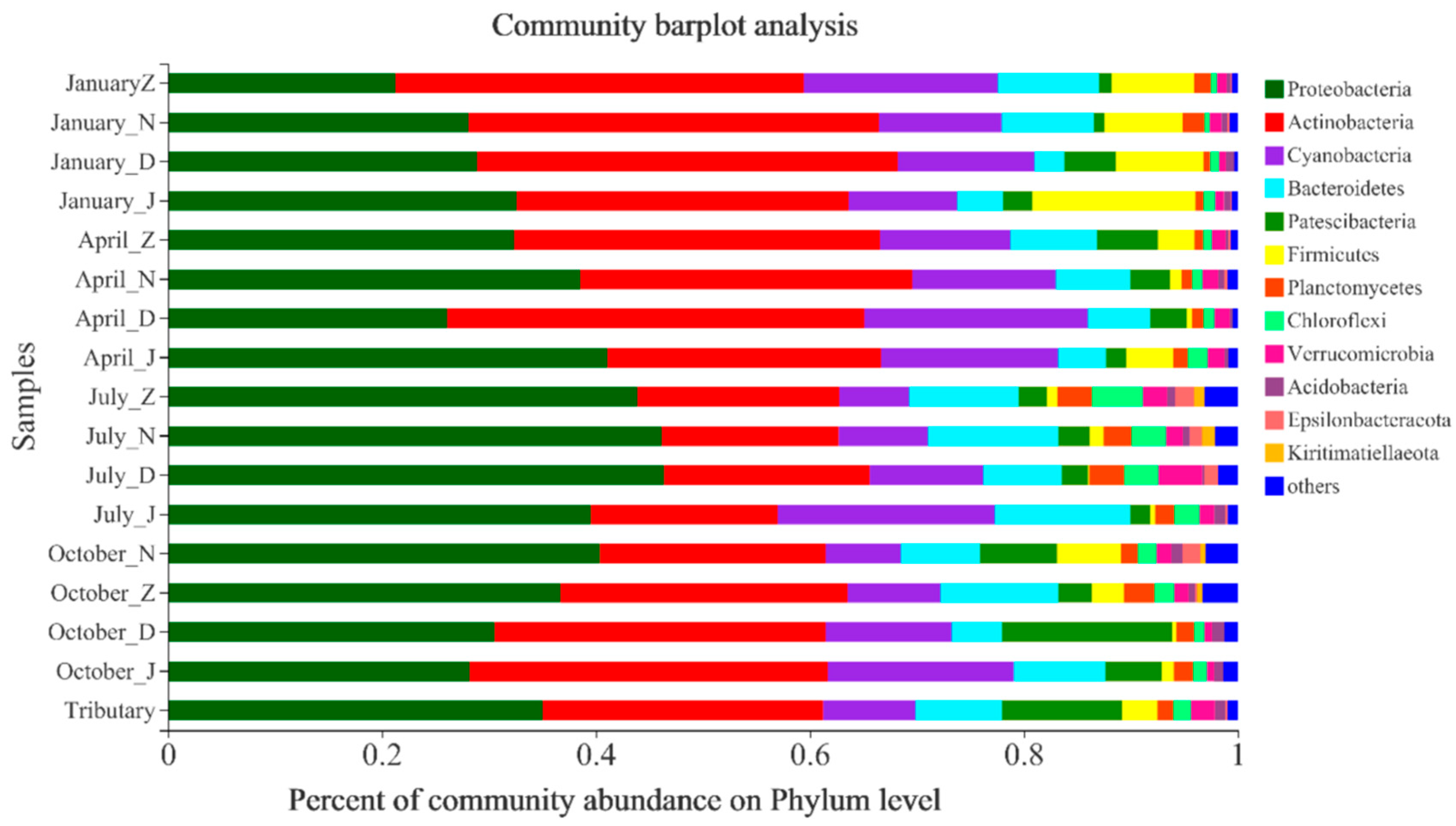

3.4. Temporal and Spatial Variation in Microbial Communities

4. Discussion

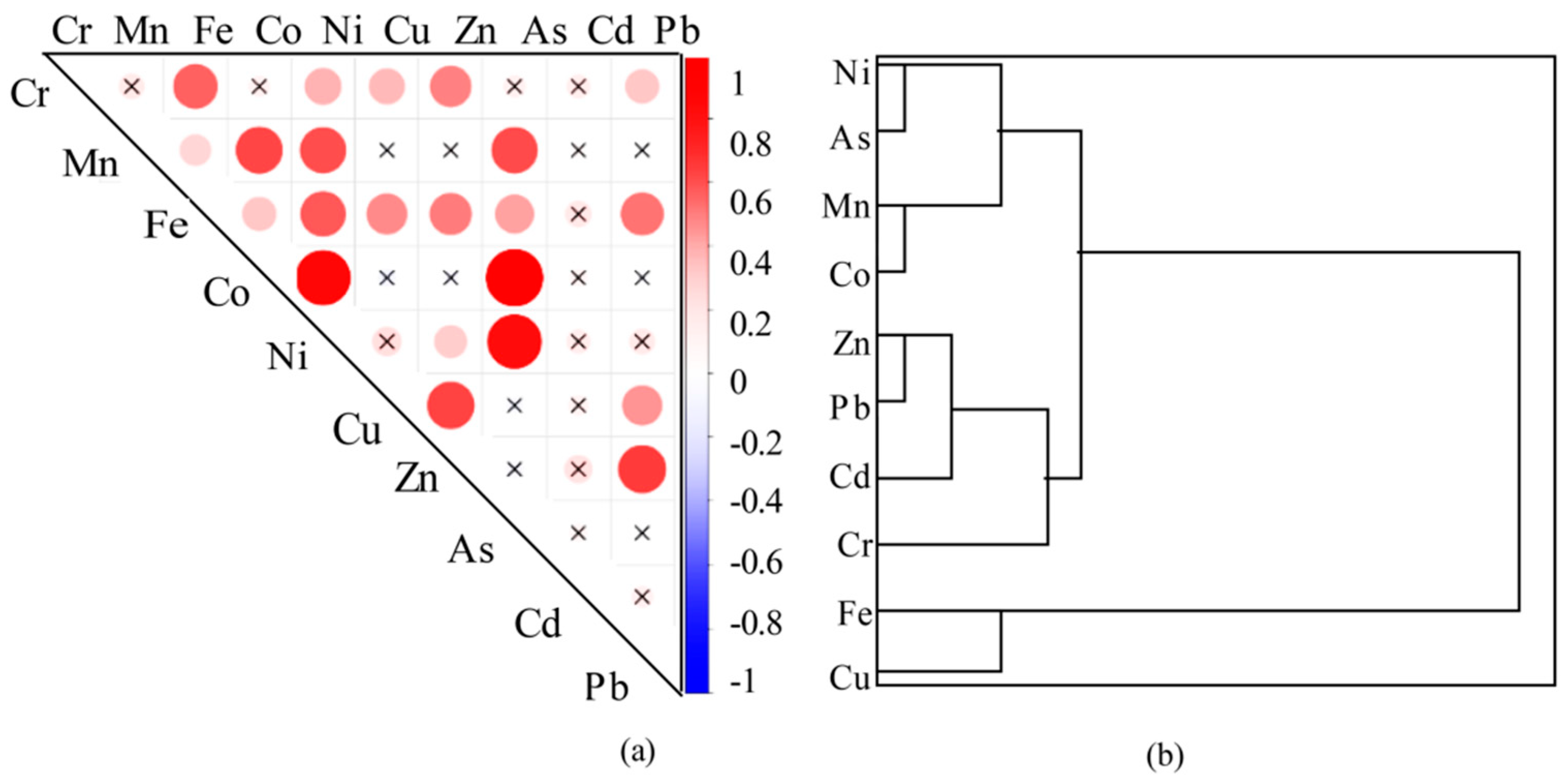

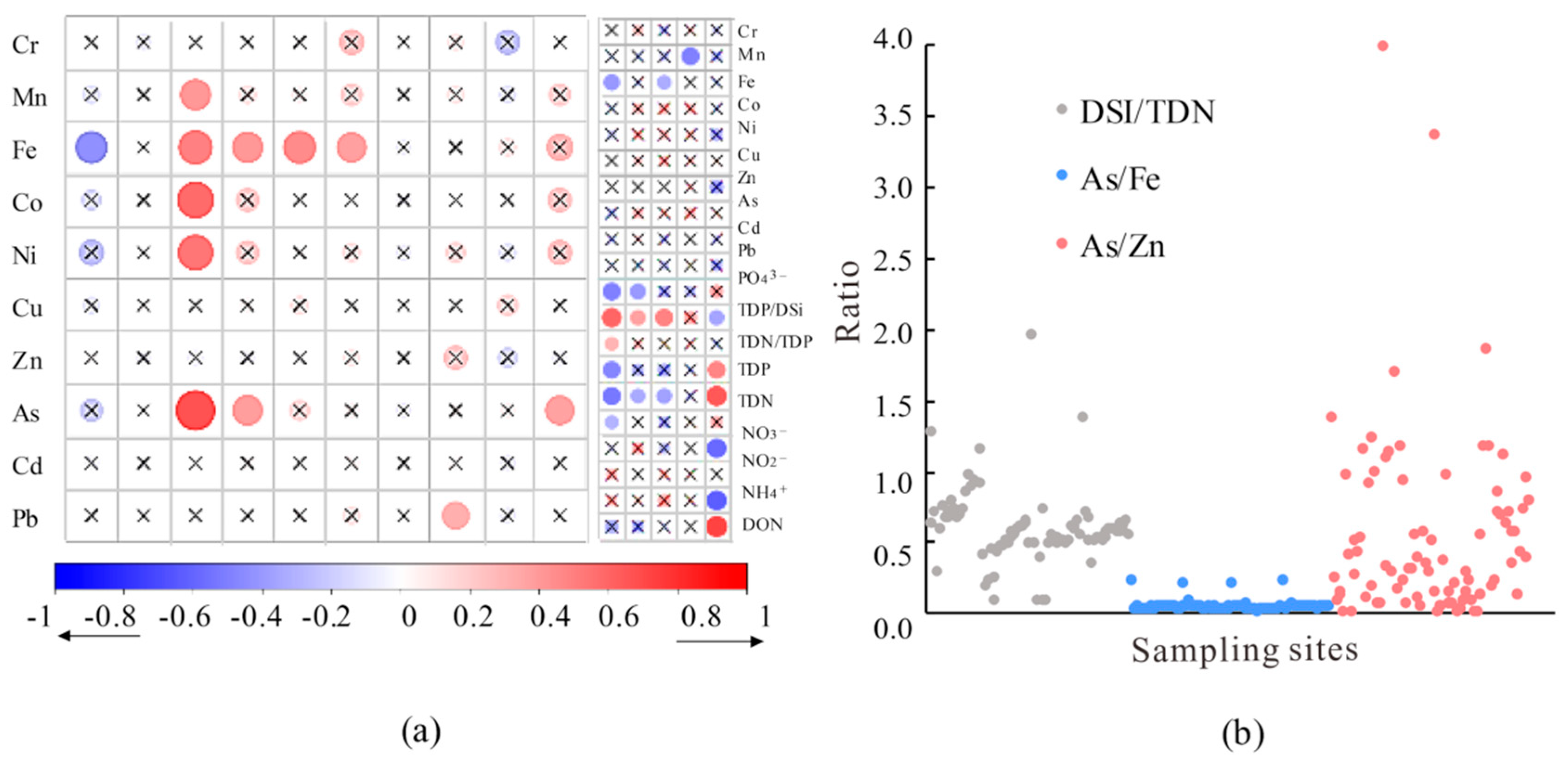

4.1. Source Analysis of Heavy Metals

4.2. Microbial Mechanisms Influencing Heavy Metals

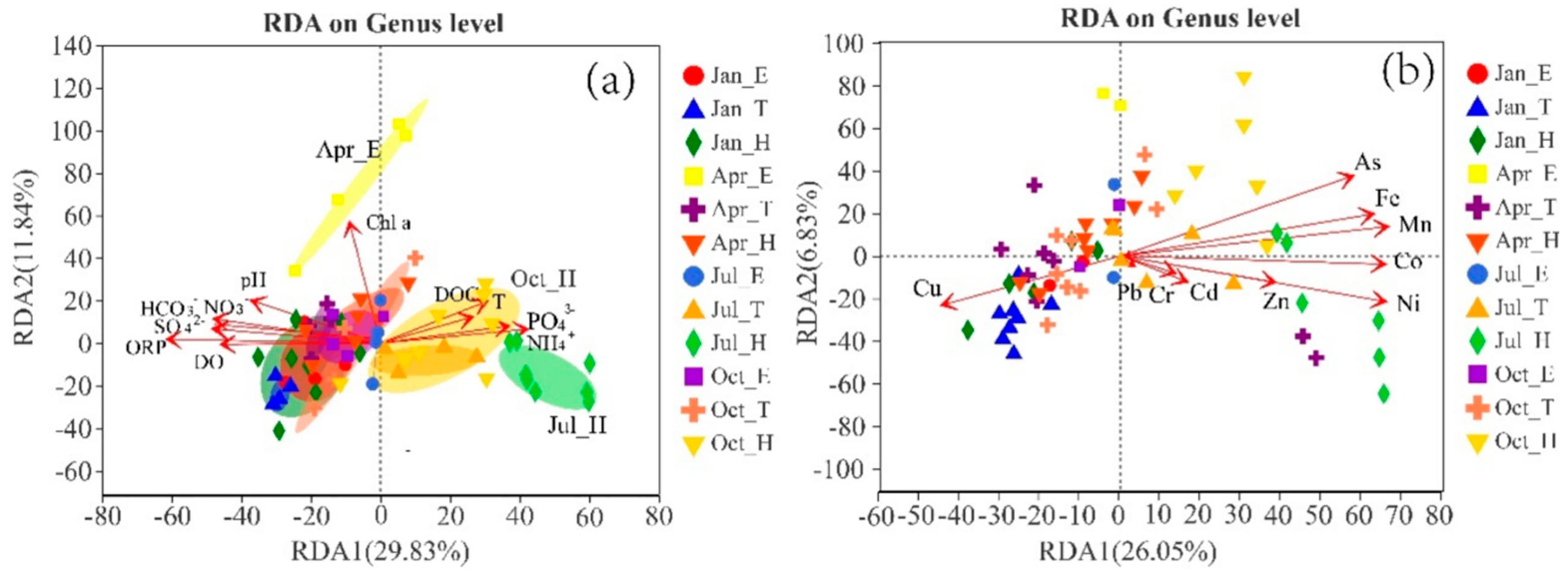

4.2.1. Environmental Factors Influencing Heavy Metals and Microorganisms

4.2.2. Mechanism of Coupling Between Heavy Metals, Nutrients, and Microorganisms in Reservoirs

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The As, Ni, Co, and Mn present in the water body of the study area are likely to predominantly originate from mine wastewater. The Zn, Pb, Cd, and Cr in the water body are primarily associated with domestic and agricultural sewage, as well as traffic emissions. Meanwhile, the Fe and Cu in the water body are sourced from natural origins.

- (2)

- Hypoxia serves as the most critical factor in expediting the cycling of nutrient salts and heavy metal elements in bottom water bodies. The O2 content plays a pivotal role in regulating processes such as sulfate reduction, nitrate reduction, Fe reduction, and arsenate reduction. The microbial-mediated biogeochemical cycling of elements, encompassing anaerobic decomposition of organic matter, sulfate reduction, nitrate reduction, sulfide oxidation, and anaerobic ammonium oxidation, influences the reductive dissolution of iron (oxy) hydroxides in suspended particulate matter and surface sediments, as well as the redox reactions of arsenic compounds. This, in turn, facilitates the accumulation of Fe, As, PO43−, and DSi in the anoxic bottom waters and may elevate their concentrations throughout the water column during mixing periods, potentially leading to eutrophication and heavy metal contamination.

- (3)

- Therefore, monitoring the real-time O2 concentration in water bodies aids in understanding the dynamic variations in their redox conditions, thereby enabling the prediction of coupled nutrient and heavy metal processes, and providing data support for preventive measures in reservoir management. Additionally, the composition of microbial communities can reflect the redox conditions of water bodies, the biogeochemical cycling of elements, the rates of redox processes, as well as the occurrence and intensity of microbial-mediated Fe and As redox reactions. Periodic monitoring of changes in water body microbial communities can also effectively forecast trends in the biogeochemical processes of nutrients and heavy metals, and offer reasonable reservoir management strategies from a microbial ecology standpoint.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kucuksezgin, F.; Kontas, A.; Altay, O.; Uluturhan, E.; Darilmaz, E. Assessment of marine pollution in Izmir Bay: Nutrient, heavy metal and total hydrocarbon concentrations. Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.M.K.; Li, P.; Fida, M. Groundwater nitrate pollution due to excessive use of N-fertilizers in rural areas of Bangladesh: Pollution status, health risk, source contribution, and future impact. Expo. Health 2024, 16, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Ding, S.; Dai, W.; Shi, R.; Cui, G.; Li, X. Application of machine learning in soil heavy metals pollution assessment in the southeastern Tibetan plateau. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkko, H.; Lukkari, K.; Sihvonen, L.M.; Kaarina, S.; Mirja, L.; Matias, R.; Lars, P.; Christina, L.; Vishal, S. Bacteria contribute to sediment nutrient release and reflect progressed Eutrophication-driven hypoxia in an organic-rich continental sea. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Wang, B.; Xiao, J.; Qiu, X.; Li, X. Water column stability driving the succession of phytoplankton functional groups in karst hydroelectric reservoirs. J. Hydrol. 2021, 592, 125607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ma, J.; Liu, Q.; Dou, L.; Qu, Y.; Shi, H.; Sum, Y.; Chen, H.; Tian, Y.; Wu, F. Accurate predication of soil heavy metal pollution using an improved machine learning method: A case study in the Pearl River Delta, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 17751–17761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; Lin, L.; Bai, L.; Yang, M.; Wang, W.; Wu, X.; Wang, D. A retrospective analysis of heavy metals and multi elements in the Yangtze River Basin: Distribution characteristics, migration tendencies and ecological risk assessment. Water Res. 2024, 254, 121385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bian, H.; Shen, C.; Deng, C.; Huang, J.H.; Liang, R.T.; Wong, M.H.; Shan, S.D.; Zhang, J. Reducing Arsenic, Cadmium, and Lead Exposure in Urban Areas via Limiting Nutrient Discharges into Rivers. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Sun, H.; Ren, C.; Yu, Y.; Pei, F.; Li, Y. Distribution, mobilization, risk assessment and source identification of heavy metals and nutrients in surface sediments of three urban-rural rivers after long-term water pollution treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 932, 172894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yu, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Feng, S.; Wu, S.; Wong, M. Urbanization impairs surface water quality: Eutrophication and metal stress in the Grand Canal of China. River Res. Appl. 2012, 28, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Cui, J.; Shan, B.; Chao, W.; Zhang, W. Heavy metal accumulation by periphyton is related to eutrophication in the Hai River Basin, Northern China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Shi, R.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, Z.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Cui, G.; Ding, S. Factors and Mechanisms Affecting Arsenic Migration in Cultivated Soils Irrigated with Contained Arsenic Brackish Groundwater. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, S.; Lv, H.; Cui, G.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Guan, T.; Li, X. Microbial controls on heavy metals and nutrients simultaneous release in a seasonally stratified reservoir. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 1937–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Li, X.; Yang, M.; Ding, S.; Ding, H. Insight into the mechanisms of denitrification and sulfate reduction coexistence in cascade reservoirs of the Jialing River: Evidence from a multi-isotope approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Cui, J.; Ding, S.; Li, S.; Yang, M.; Dai, W.; Li, Y. Artificial regulation affects nitrate sources and transformations in cascade reservoirs by altering hydrological conditions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 381, 125225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Yu, M.; Hu, B.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Z.Q. Analysis and assessment of the nutrients, biochemical indexes and heavy metals in the Three Gorges Reservoir, China, from 2008 to 2013. Water Res. 2016, 92, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, G.; Tang, Y.; Xu, Z. Fluvial geochemistry of rivers draining karst terrain in Southwest China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2010, 38, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T.R.; Maita, Y.; Lalli, C.M. A Manual of Chemical and Biological Methods for Seawater Analysis; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1984; Volume 173. [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Exp. Suppl. 2012, 101, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chai, C.; Yu, Z.M.; Shen, Z.L.; Song, X.; Cao, X.; Yao, Y. Nutrient characteristics in the Yangtze River Estuary and the adjacent East China Sea before and after impoundment of the Three Gorges Dam. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 4687–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB5749-2006; Standards for Drinking Water Quality. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Malik, A.; Kumar, V.; Renu; Sunil; Kumar, T. World health organization’s guidelines for stability testing of pharmaceutical products. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2011, 3, 892. [Google Scholar]

- Ouz, Y.; James, W.; Murray, S.T. Trace metal composition of suspended particulate matter in the water column of the Black Sea. Mar. Chem. 2011, 126, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Tu, Q. Guidelines for Eutrophication Investigation of Lakes, 2nd ed.; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tessier, A.; Fortin, D.; Belzile, N.; Devitre, R.R.; Leppard, G.G. Metal sorption to diagenetic iron and manganese oxyhydroxides and associated organic matter: Narrowing the gap between field and laboratory measurements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; Zeng, W.; Wu, C.; Chen, G.; Meng, Q.; Hao, X.; Peng, Y. Impact of organic carbon on sulfide-driven autotrophic denitrification: Insight from isotope fractionation and functional genes. Water Res. 2024, 255, 121507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Lu, Y.; Nie, W.; Evans, P.; Wang, X.; Dang, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Ren, N.; Xie, G. Nitrate-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation coupled to Fe (III) reduction as a source of ammonium and nitrous oxide. Water Res. 2024, 256, 121571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, R.; Delaney, M.; Widdel, F.; Stahl, D.A. Natural relationships among sulfate-reducing eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 6689–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Pan, H.; Guo, X.; Lu, D.; Yang, Y. Sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB) in the Yangtze Estuary sediments: Abundance, distribution and implications for the bioavailibility of metals. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhou, Y.; Jia, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, X. Sulfur Cycling-Related Biogeochemical Processes of Arsenic Mobilization in the Western Hetao Basin, China: Evidence from Multiple Isotope Approaches. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 12650–12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, G.; Cui, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, W.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, T. Study on the Source and Microbial Mechanisms Influencing Heavy Metals and Nutrients in a Subtropical Deep-Water Reservoir. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122750

Cui G, Cui J, Zhang M, Zhang B, Huang Y, Wang Y, Feng W, Zhou J, Liu Y, Li T. Study on the Source and Microbial Mechanisms Influencing Heavy Metals and Nutrients in a Subtropical Deep-Water Reservoir. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122750

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Gaoyang, Jiaoyan Cui, Mengke Zhang, Boning Zhang, Yingying Huang, Yiheng Wang, Wanfu Feng, Jiliang Zhou, Yong Liu, and Tao Li. 2025. "Study on the Source and Microbial Mechanisms Influencing Heavy Metals and Nutrients in a Subtropical Deep-Water Reservoir" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122750

APA StyleCui, G., Cui, J., Zhang, M., Zhang, B., Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Feng, W., Zhou, J., Liu, Y., & Li, T. (2025). Study on the Source and Microbial Mechanisms Influencing Heavy Metals and Nutrients in a Subtropical Deep-Water Reservoir. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2750. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122750