Hospital Wastewater Surveillance and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes That Are Identified in Hospital Wastewater

3.1. Carbapenem Resistance Related Genes

3.2. 3rd Generation Cephalosporin Resistance Related Genes

3.3. Colistin Resistance Related Genes

3.4. Vancomycin Resistance and Methicillin Resistance Related Genes

3.5. Sulfonamide Resistance Genes

3.6. Tetracycline Resistance Genes

4. Methods of ARGs Identification in Hospital Wastewater

4.1. Culture-Based Approaches

4.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)-Based Methods

4.3. Microarray Technology

4.4. Next-Generation Sequencing Techniques

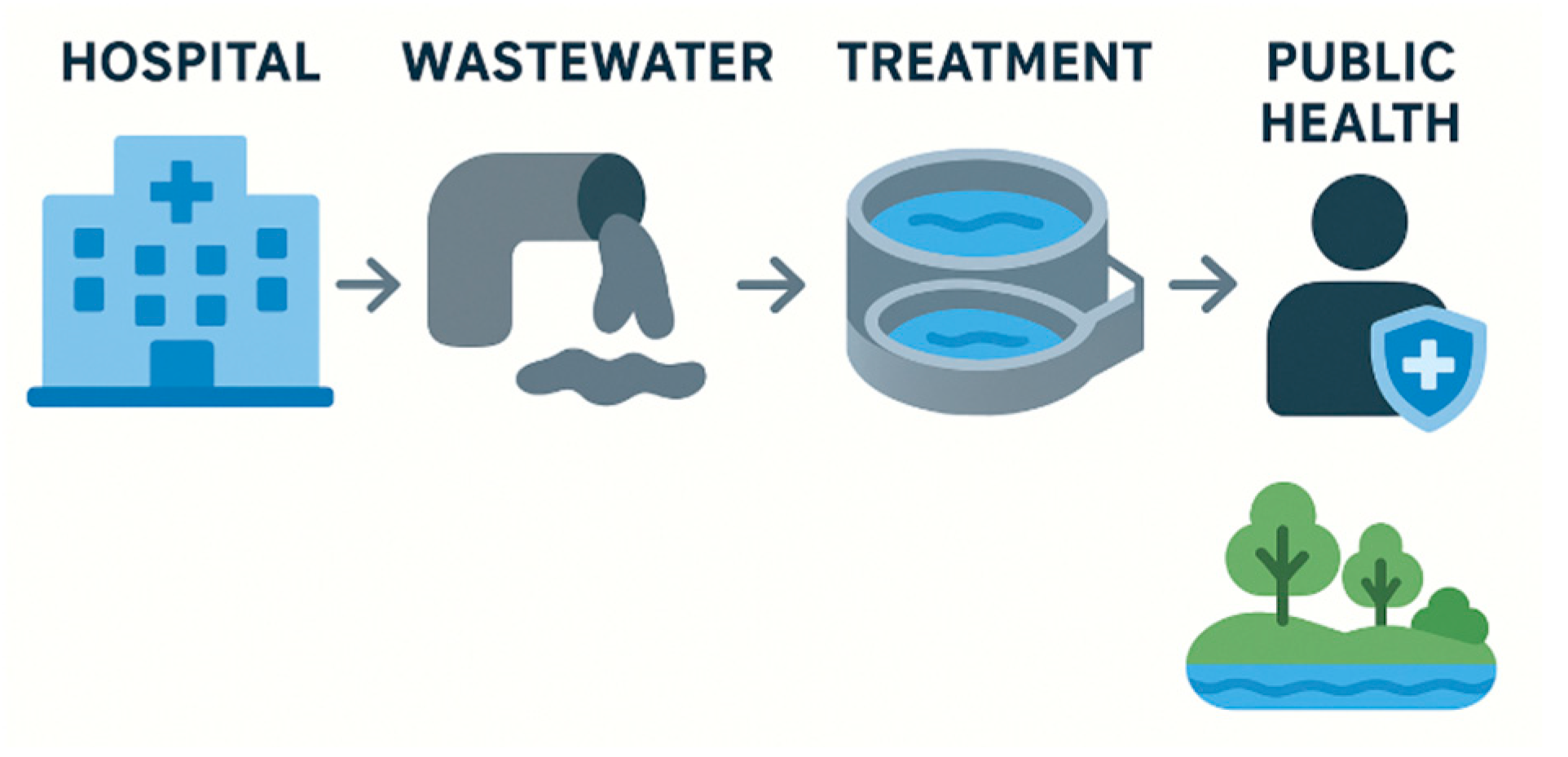

5. The Role of Hospital Wastewater Surveillance in Antimicrobial Resistance

6. Role of Hospital Wastewater Treatment Plants

7. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | antimicrobial resistance |

| ARGs | antibiotic resistance genes |

| ARB | antimicrobial resistance bacteria |

| DDD | daily defined dose |

| DOT | days of therapy |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention |

| ESBL | extended spectrum beta lactamase |

| ESKAPEE | Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp., Escherichia coli |

| HWWS | hospital wastewater surveillance |

| KPC | klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase |

| MCR | mobilized colistin resistance |

| MGEs | mobile genetic elements |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MRSA | methicillin resistance staphylococcus aureus |

| dPCR | digital polymerase chain reaction |

| dd-PCR | digital polymerase chain reaction |

| HT qPCR | high-throughput analysis and visualization of quantitative real-time PCR |

| qPCR | quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription-polymerase Chain Reaction |

| VRE | vancomycin resistance enterococcus |

| WGS | whole genome sequencing |

| WWS | wastewater surveillance |

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, Y.; Bumyut, A.; Precha, N.; Sirikanchana, K.; Haramoto, E.; Makkaew, P. Multidrug antibiotic resistance in hospital wastewater as a reflection of antibiotic prescription and infection cases. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Assessing the Health Burden of Infections with Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the EU/EEA, 2016–2020; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/publications/assessing-health-burden-infections-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria-eueea-2016-2020_en (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net)—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/surveillance-antimicrobial-resistance-europe-2022 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Singh, S.; Ahmed, A.I.; Almansoori, S.; Alameri, S.; Adlan, A.; Odivilas, G.; Chattaway, M.A.; Bin Salem, S.; Brudecki, G.; Elamin, W. A narrative review of wastewater surveillance: Pathogens of concern, applications, detection methods, and challenges. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1445961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärnänen, K.M.M.; Narciso-Da-Rocha, C.; Kneis, D.; Berendonk, T.U.; Cacace, D.; Do, T.T.; Elpers, C.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Henriques, I.; Jaeger, T.; et al. Antibiotic resistance in European wastewater treatment plants mirrors the pattern of clinical antibiotic resistance prevalence. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau9124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarestrup, F.M.; Woolhouse, M.E.J. Using sewage for surveillance of antimicrobial resistance. Science 2020, 367, 630–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.; Kurittu, P.; Al-Mustapha, A.I.; Heljanko, V.; Johansson, V.; Thakali, O.; Mishra, S.K.; Lehto, K.-M.; Lipponen, A.; Oikarinen, S.; et al. Wastewater surveillance of antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens: A systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 977106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, L.; Achi, C.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H. Ranking the risk of antibiotic resistance genes by metagenomic and multifactorial analysis in hospital wastewater systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health-Care Waste: Key Facts. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Chau, K.; Barker, L.; Budgell, E.; Vihta, K.; Sims, N.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Harriss, E.; Crook, D.; Read, D.; Walker, A.; et al. Systematic review of wastewater surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in human populations. Environ. Int. 2022, 162, 107171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounmanou, Y.M.G.; Houefonde, A.; I-CRECT Consortium; Nguyen, T.T.; Dalsgaard, A. Mitigating antimicrobial resistance through effective hospital wastewater management in low- and middle-income countries. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1525873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarde-López, M.; Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Bobadilla-Del-Valle, M.; Carrillo-Quiroz, B.A.; Cornejo-Juárez, P.; Ponce-De-León, A.; Sassoé-González, A.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Hospital Wastewater: Identification of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella spp. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarde-López, M.; Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Godoy-Lozano, E.E.; Carrillo-Quiroz, B.A.; Cornejo-Juárez, P.; Sassoé-González, A.; Ponce-de-León, A.; Saturno-Hernández, P.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Presence and Persistence of ESKAPEE Bacteria before and after Hospital Wastewater Treatment. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoesser, N.; George, R.; Aiken, Z.; Phan, H.T.T.; Lipworth, S.; Quan, T.P.; Mathers, A.J.; De Maio, N.; Seale, A.C.; Eyre, D.W.; et al. Genomic epidemiology and longitudinal sampling of ward wastewater environments and patients reveals complexity of the transmission dynamics of bla KPC-carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in a hospital setting. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 6, dlae140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Krolicka, A.; Tran, T.T.; Räisänen, K.; Ásmundsdóttir, Á.M.; Wikmark, O.-G.; Lood, R.; Pitkänen, T. Antibiotic resistance monitoring in wastewater in the Nordic countries: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2024, 246, 118052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Blas, J.F.; Agüi, C.V.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Serna, C.; Montero, N.; Saba, C.K.S.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B. Dissemination Routes of Carbapenem and Pan-Aminoglycoside Resistance Mechanisms in Hospital and Urban Wastewater Canalizations of Ghana. mSystems 2022, 7, e0101921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.R.; Lepper, H.C.; McNally, L.; Wee, B.A.; Munk, P.; Warr, A.; Moore, B.; Kalima, P.; Philip, C.; de Roda Husman, A.M.; et al. Secrets of the Hospital Underbelly: Patterns of Abundance of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Hospital Wastewater Vary by Specific Antimicrobial and Bacterial Family. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 703560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarde-López, M.; Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Bobadilla-del-Valle, M.; Cornejo-Juárez, P.; Carrillo-Quiroz, B.A.; Ponce-de-León, A.; Sassoé-González, A.; Saturno-Hernández, P.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns and Clonal Distribution of E. coli, Enterobacter spp. and Acinetobacter spp. Strains Isolated from Two Hospital Wastewater Plants. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, M.E.; Webster, G.; Perry, W.B.; Baldwin, A.; Rushton, L.; Pass, D.A.; Cross, G.; Durance, I.; Muziasari, W.; Kille, P.; et al. National-scale antimicrobial resistance surveillance in wastewater: A comparative analysis of HT qPCR and metagenomic approaches. Water Res. 2024, 262, 121989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, M.G.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Mohamed, N.; Hermsen, E.D.; Kamat, S.; Townsend, A.; Brink, A.; Soriano, A.; Paterson, D.L.; Moore, L.S.; et al. Global trends in carbapenem- and difficult-to-treat-resistance among World Health Organization priority bacterial pathogens: ATLAS surveillance program 2018–2022. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 37, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talat, A.; Blake, K.S.; Dantas, G.; Khan, A.U. Metagenomic Insight into Microbiome and Antibiotic Resistance Genes of High Clinical Concern in Urban and Rural Hospital Wastewater of Northern India Origin: A Major Reservoir of Antimicrobial Resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0410222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, C.; Giménez, M.; Riera, N.; Parada, A.; Puig, J.; Galiana, A.; Grill, F.; Vieytes, M.; Mason, C.E.; Antelo, V.; et al. Human microbiota drives hospital-associated antimicrobial resistance dissemination in the urban environment and mirrors patient case rates. Microbiome 2022, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, E.A.; Ramirez, D.; Balcázar, J.L.; Jiménez, J.N. Metagenomic analysis of urban wastewater resistome and mobilome: A support for antimicrobial resistance surveillance in an endemic country. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erler, T.; Droop, F.; Lübbert, C.; Knobloch, J.K.; Carlsen, L.; Papan, C.; Schwanz, T.; Zweigner, J.; Dengler, J.; Hoffmann, M.; et al. Analysing carbapenemases in hospital wastewater: Insights from intracellular and extracellular DNA using qPCR and digital PCR. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175344. [Google Scholar]

- Castanheira, M.; Simner, P.J.; A Bradford, P. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: An update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husna, A.; Rahman, M.; Badruzzaman, A.T.M.; Sikder, M.H.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, T.; Alam, J.; Ashour, H.M. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases (ESBL): Challenges and Opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaatout, N.; Bouras, S.; Slimani, N. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae in wastewater: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Water Health 2021, 19, 705–723. [Google Scholar]

- Gharaibeh, M.H.; Al Sheyab, S.Y.; Lafi, S.Q.; Etoom, E.M. Risk factors associated with mcr-1 colistin-resistance gene in Escherichia coli broiler samples in northern Jordan. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 36, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, N.; Kannan, A.; Holton, E.; Jagadeesan, K.; Mageiros, L.; Standerwick, R.; Craft, T.; Barden, R.; Feil, E.J.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistance genes in a one-year city metabolism longitudinal study using wastewater-based epidemiology. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122020. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, J.P.R.; Rosa, R.d.S.; Ramos, M.S.; Lopes, R.; dos Santos, L.D.R.; Savazzi, E.A.; Stehling, E.G. Convergence of mcr-1 and broad-spectrum β-lactamase genes in Escherichia coli strains from the environmental sector. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 362, 124937. [Google Scholar]

- Mmatli, M.; Mbelle, N.M.; Sekyere, J.O. Global epidemiology, genetic environment, risk factors and therapeutic prospects of mcr genes: A current and emerging update. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 9413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, H.; Kuroda, M.; Sekizuka, T.; Kanamori, H. Highly sensitive detection of antimicrobial resistance genes in hospital wastewater using the multiplex hybrid capture target enrichment. mSphere 2023, 8, e0010023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellis, K.L.; Dissanayake, O.M.; Harrison, E.M.; Aggarwal, D. Community methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus outbreaks in areas of low prevalence. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 31, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, Y.; Ito, T.; Hiramatsu, K. A New Class of Genetic Element, Staphylococcus Cassette Chromosome mec, Encodes Methicillin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittorakis, E.; Vica, M.L.; Zervaki, C.O.; Vittorakis, E.; Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, V.E.; Schürger, M.E.; Neculicioiu, V.S.; Papadomanolaki, E.; Junie, L.M. A Comparative Analysis of MRSA: Epidemiology and Antibiotic Resistance in Greece and Romania. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjesson, S.; Melin, S.; Matussek, A.; Lindgren, P.-E. A seasonal study of the mecA gene and Staphylococcus aureus including methicillin-resistant S. aureus in a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 2009, 43, 925–932, Erratum in Water Res. 2009, 43, 3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.-Z.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Zu, W.-B.; Wang, H.; Bai, L.-Y.; Zhou, Z.-S.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Wang, Z.-J.; Luo, X.-D. Structure optimizing of flavonoids against both MRSA and VRE. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 271, 116401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odih, E.E.; Sunmonu, G.T.; Okeke, I.N.; Dalsgaard, A. NDM-1- and OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in wastewater of a Nigerian hospital. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0238123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teban-Man, A.; Szekeres, E.; Fang, P.; Klümper, U.; Hegedus, A.; Baricz, A.; Berendonk, T.U.; Pârvu, M.; Coman, C. Municipal Wastewaters Carry Important Carbapenemase Genes Independent of Hospital Input and Can Mirror Clinical Resistance Patterns. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0271121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbait, G.D.; Daou, M.; Abuoudah, M.; Elmekawy, A.; Hasan, S.W.; Everett, D.B.; Alsafar, H.; Henschel, A.; Yousef, A.F. Comparison of qPCR and metagenomic sequencing methods for quantifying antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, Z.; Liu, W.; Stapleton, L.; Kenters, N.; Dewi, D.A.R.; Gudes, O.; Ziochos, H.; Khan, S.J.; Power, K.; McLaws, M.-L.; et al. Wastewater-based monitoring reveals geospatial-temporal trends for antibiotic-resistant pathogens in a large urban community. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 325, 121403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puttaswamygowda, G.H.; Olakkaran, S.; Antony, A.; Kizhakke Purayil, A. Chapter 22: Present Status and Future Perspectives of Marine Actinobacterial Metabolites. In Recent Developments in Applied Microbiology and Biochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Dudek-Wicher, R. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Kannan, E.P.; Hakami, O.; Alamri, A.A.; Gopal, J.; Muthu, M. Reviewing the Phenomenon of Antimicrobial Resistance in Hospital and Municipal Wastewaters: The Crisis, the Challenges and Mitigation Methods. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Cao, Y.; Li, B. Hospital Wastewater as a Reservoir for Antibiotic Resistance Genes: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 574968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.-C.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Tsai, H.-L.; Chang, T.-K.; Yin, T.-C.; Huang, C.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Li, C.-C.; Chen, P.-J.; Liu, Y.-R.; et al. Comparison of Next-Generation Sequencing and Polymerase Chain Reaction for Personalized Treatment-Related Genomic Status in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 1552–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dropa, M.; da Silva, J.S.B.; Andrade, A.F.C.; Nakasone, D.H.; Cunha, M.P.V.; Ribeiro, G.; de Araújo, R.S.; Brandão, C.J.; Ghiglione, B.; Lincopan, N.; et al. Spread and persistence of antimicrobial resistance genes in wastewater from human and animal sources in São Paulo, Brazil. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2024, 29, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavé, L.; Brothier, E.; Abrouk, D.; Bouda, P.S.; Hien, E.; Nazaret, S. Efficiency and sensitivity of the digital droplet PCR for the quantification of antibiotic resistance genes in soils and organic residues. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 10597–10608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutuku, C.; Melegh, S.; Kovacs, K.; Urban, P.; Virág, E.; Heninger, R.; Herczeg, R.; Sonnevend, Á.; Gyenesei, A.; Fekete, C.; et al. Characterization of β-Lactamases and Multidrug Resistance Mechanisms in Enterobacterales from Hospital Effluents and Wastewater Treatment Plant. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutinel, M.; Larsson, D.J.; Flach, C.-F. Antibiotic resistance genes of emerging concern in municipal and hospital wastewater from a major Swedish city. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 151433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.F.; Zankari, E.; Hasman, H. Molecular Methods for Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endimiani, A.; Hujer, A.M.; Hujer, K.M.; Gatta, J.A.; Schriver, A.C.; Jacobs, M.R.; Rice, L.B.; Bonomo, R.A. Evaluation of a Commercial Microarray System for Detection of SHV-, TEM-, CTX-M-, and KPC-Type β-Lactamase Genes in Gram-Negative Isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 2618–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, L.; Prossomariti, D.; Alcolea-Medina, A.; Sasson, M.; Dibbens, M.; Al-Yaakoubi, N.; Humayun, G.; Charalampous, T.; Alder, C.; Ward, D.; et al. The drainome: Longitudinal metagenomic characterization of wastewater from hospital ward sinks to characterize the microbiome and resistome and to assess the effects of decontamination interventions. J. Hosp. Infect. 2024, 153, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Coin, L.; O’brien, J.; Hai, F.; Jiang, G. Molecular Methods for Pathogenic Bacteria Detection and Recent Advances in Wastewater Analysis. Water 2021, 13, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majlander, J.; Anttila, V.-J.; Nurmi, W.; Seppälä, A.; Tiedje, J.; Muziasari, W. Routine wastewater-based monitoring of antibiotic resistance in two Finnish hospitals: Focus on carbapenem resistance genes and genes associated with bacteria causing hospital-acquired infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 117, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huijbers, P.M.C.; Camacho, J.B.; Hutinel, M.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Flach, C.-F. Sampling Considerations for Wastewater Surveillance of Antibiotic Resistance in Fecal Bacteria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cason, C.; D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Mazzacane, S.; Comar, M.; Caselli, E. Next-generation sequencing and PCR technologies in monitoring the hospital microbiome and its drug resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 969863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, S.A.; Jansen, R.; Hays, J.P. Understanding and overcoming the pitfalls and biases of next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods for use in the routine clinical microbiological diagnostic laboratory. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, M.; Guo, X.; Wang, M.; Bilal, H.; Xin, L.; Yuan, Y.; Yao, F.; Sheikh, T.M.M.; Khan, M.N.; Jiao, X. Integrative metagenomic dissection of last-resort antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in hospital wastewaters. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 174930. [Google Scholar]

- Hassard, F.; Bajón-Fernández, Y.; Castro-Gutierrez, V. Wastewater-based epidemiology for surveillance of infectious diseases in healthcare settings. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 36, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, A.; Salih, M.; Abdelrahman, H.; Al Mana, H.; Hadi, H.; Eltai, N. Wastewater-based epidemiology for tracking bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance in COVID-19 isolation hospitals in Qatar. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 141, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, D.; Pan, Q.; Weng, L.; Huang, W.; Zhao, J.; Lan, W.; Shi, Q.; Yu, Y.; et al. Evaluating the effects of hospital wastewater treatment on bacterial composition and antimicrobial resistome. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1620677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.C.; Gowda, L.S.; Jacob, A.M.; Shetty, K.; Shetty, A.V. Surveillance of Multidrug-Resistant Genes in Clinically Significant Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolated from Hospital Wastewater. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambaza, S.S.; Naicker, N. Contribution of wastewater to antimicrobial resistance: A review article. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 34, 23–29, Erratum in Lancet 2022, 400, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, N.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Future perspectives of wastewater-based epidemiology: Monitoring infectious disease spread and resistance to the community level. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antibiotic Class | Key Resistance Genes | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Carbapenems | bla_KPC, bla_NDM, bla_VIM, bla_OXA-48, bla_IMP | Carbapenemase production leading to β-lactam degradation |

| B-lactams | bla_CTX-M, bla_SHV, bla_TEM, bla_OXA-ESBLs | Hydrolyze third-generation cephalosporins |

| Colistin | mcr-1 to mcr-10, pmrA, pmrB | Modification of lipid A reducing colistin binding |

| Tetracyclines | tetA, tetB, tetM, tetO, tetX, tetC, tetD, tetG | Efflux pumps and ribosomal protection proteins |

| Sulfonamides | sul1, sul2, sul3 | Altered dihydropteroate synthase |

| Vancomycin | vanA, vanB, vanC, vanD, vanE, vanG, vanL, vanM, vanN | Modified peptidoglycan precursors reducing binding |

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages | Key Applications in Hospital Wastewater Surveillance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-Based Approach | Reliable for identifying viable bacteria which have clinical significance (proof of existence) | Unable to detect non-culturable bacteria (only ~1–3% of environmental bacteria can be cultured) | Useful for detailed susceptibility testing and resistance pattern analysis |

| Enables susceptibility testing to determine resistance patterns | Bacteria often die quickly when exposed to non-native environmental conditions | May miss non-culturable or difficult-to-culture organisms | |

| qPCR (Quantitative PCR) | High sensitivity and specificity, detects hard-to-culture bacteria | Requires prior information on target sequence for assay design | Effective for rapid detection of target ARGs, even at low concentrations |

| Can detect low-abundance ARGs, allowing early outbreak detection | Limited to preselected ARGs, unable to detect non-targeted or novel ARGs | Suitable for focused surveillance of known resistance genes in wastewater | |

| Metagenomics | Detects a wide range of ARGs, including novel and divergent genes | More expensive per sample, especially if applied in small-scale applications | Comprehensive analysis for total ARG burden, capturing more gene diversity |

| More cost-effective for large sample monitoring | May be less sensitive for low-abundance ARGs compared to targeted methods | Ideal for broader surveillance across multiple resistance genes and bacteria |

| Study | Country (City) | Hospital Type | Number of Beds (If Reported) | Sampling Site | Key ARGs Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meng et al., 2025 [64] | China | Tertiary university hospital (Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Hangzhou, Eastern China) | Not reported (but HWTS processes ~10,000 tons/week, so likely large) | Influent and effluent of hospital wastewater treatment system (HWTS) | Beta-lactam (e.g., blaCTX-M, blaPER, cfxA3, blaKPC, blaVIM, blaNDM, blaIMP), aminoglycoside, macrolide, phenicol, tetracycline, vancomycin (vanH-M, vanX-M, vanM), linezolid (cfr(C), optrA), colistin (mcr-4.3, mcr-5.1), tigecycline (toprJ, toprJ1, tetX2), QAC resistance genes (qacF, qacG2) |

| Shetty et al., 2025 [65] | India | Not specifically reported | Not reported | Hospital wastewater samples, including final treated effluent | tetD, tetE, tetG (tetracycline resistance), catA1, catA2 (chloramphenicol resistance), blaNDM-1 (carbapenem resistance), qnrA, qnrB, qnrS (quinolone resistance), qepa |

| Galarde-López et al., 2024 [14] | Mexico (Mexico City Metropolitan Zone) | Two Tertiary hospitals | Not reported | Hospital wastewater effluent | Bla-KPC, bla-NDM, mcr-1, bla-Oxa48-like |

| Stoesser et al., 2024 [16] | United Kingdom (Edinburgh) | Tertiary Teaching Hospital | Not reported | Multiple wastewater collection points within hospital wards | bla_KPC, bla_NDM, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-48-like, blaOXA-58-like |

| Galarde-López et al., 2024 [20] | Mexico | Two hospital wastewater treatment plants serving general hospitals | Not reported | Hospital wastewater treatment plant effluents | Carbapenem resistance genes (e.g., bla_KPC, bla_NDM) Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes Colistin resistance genes (mcr-1 and variants) Other multidrug resistance genes found in clinical isolates of E. coli, Enterobacter spp., and Acinetobacter spp. |

| Delgado-Blas et al., 2022 [18] | Ghana | General Hospital (urban hospital wastewater canalizations) | 400 (approximately) | Hospital and urban wastewater canalizations | bla_KPC, bla_NDM, bla_VIM, mcr variants, including mcr-1 found coexisting with bla_NDM-1, ESBL genes |

| Siri et al., 2021 [3] | Thailand | General hospital | Not reported | Hospital wastewater and related wastewater treatment plant effluents | Carbapenem resistance genes (e.g., bla_KPC, bla_NDM), Extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes (bla_CTX-M, bla_SHV, bla_TEM), Colistin resistance genes (mcr genes, primarily mcr-1) |

| Perry et al., 2021 [19] | Scotland (Edinburgh) | Tertiary Teaching Hospital | Not reported | Hospital drains and wards wastewater collection points | Carbapenem resistance genes: bla_KPC, bla_NDM, bla_IMP, bla_VIM, bla_OXA-23, bla_OXA-48, bla_OXA-58, ESBL genes: bla_CTX-M, bla_SHV, bla_TEM, Colistin resistance genes: mcr-1 to mcr-10 Vancomycin resistance genes: vanA, vanB, vanC, etc., Tetracycline resistance genes: tetA, tetB, tetM, etc., Sulfonamide resistance genes: sul1, sul2, sul3, Methicillin resistance gene: mecA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lymperatou, D.; Konstantopoulou, R.; Mentsis, M.; Atzemoglou, N.; Diamanti, C.; Tzourtzos, I.; Naka, K.K.; Mitsis, M.; Konstantina, G.; Milionis, H.; et al. Hospital Wastewater Surveillance and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2739. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122739

Lymperatou D, Konstantopoulou R, Mentsis M, Atzemoglou N, Diamanti C, Tzourtzos I, Naka KK, Mitsis M, Konstantina G, Milionis H, et al. Hospital Wastewater Surveillance and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2739. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122739

Chicago/Turabian StyleLymperatou, Diamantina, Revekka Konstantopoulou, Michalis Mentsis, Natalia Atzemoglou, Christina Diamanti, Ioannis Tzourtzos, Katerina K. Naka, Michail Mitsis, Gartzonika Konstantina, Haralampos Milionis, and et al. 2025. "Hospital Wastewater Surveillance and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Narrative Review" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2739. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122739

APA StyleLymperatou, D., Konstantopoulou, R., Mentsis, M., Atzemoglou, N., Diamanti, C., Tzourtzos, I., Naka, K. K., Mitsis, M., Konstantina, G., Milionis, H., Ntzani, E., & Christaki, E. (2025). Hospital Wastewater Surveillance and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2739. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122739