Microbial Imbalance and Stochastic Assembly Drive Gut Dysbiosis in White-Gill Diseased Larimichthys crocea (Richardson, 1846)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

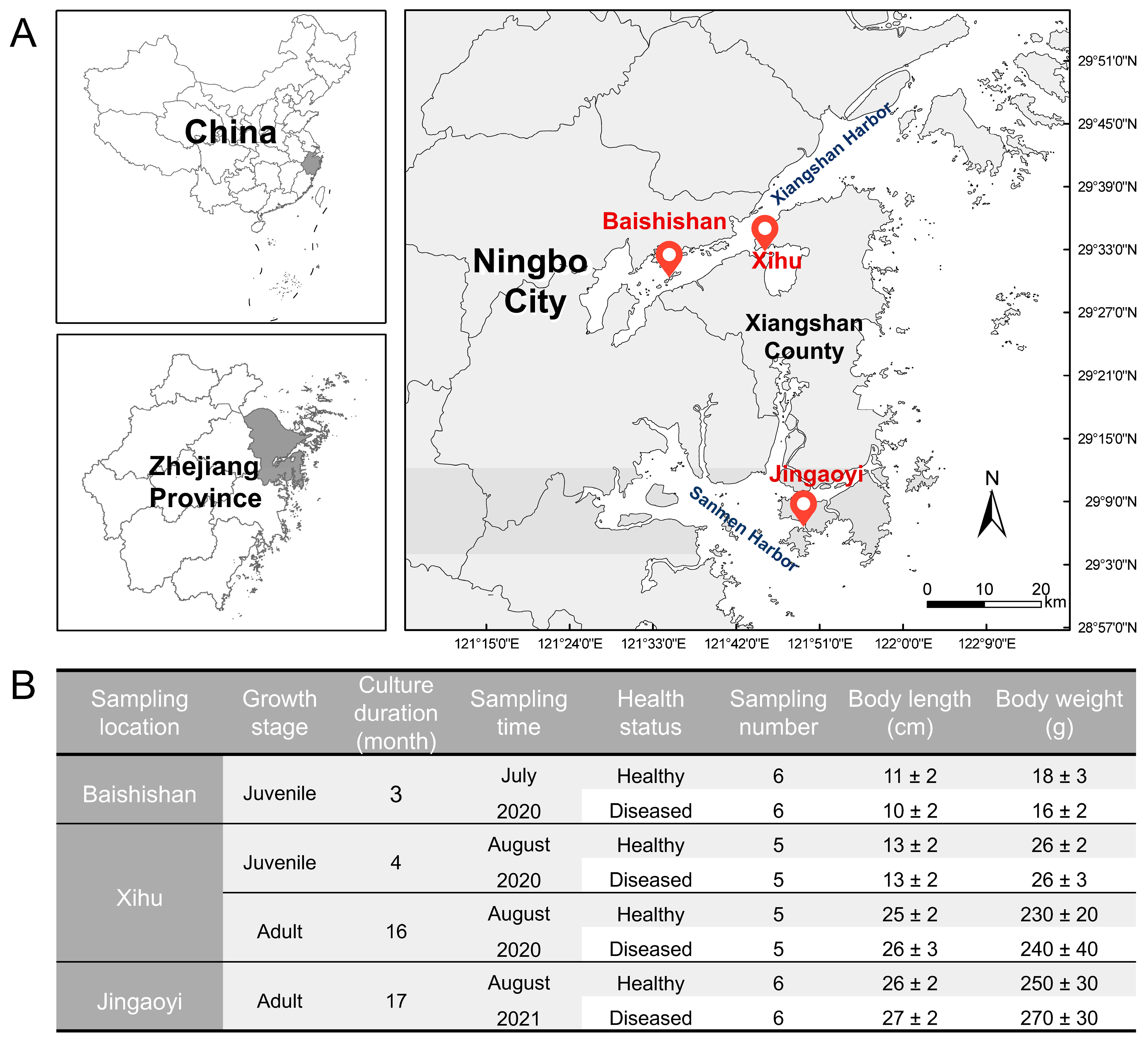

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Histopathological Examination

2.3. DNA Extraction, 16S rRNA Gene Amplification and Illumina Sequencing

2.4. Sequence Processing

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Symptoms and Histopathological Observation of White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

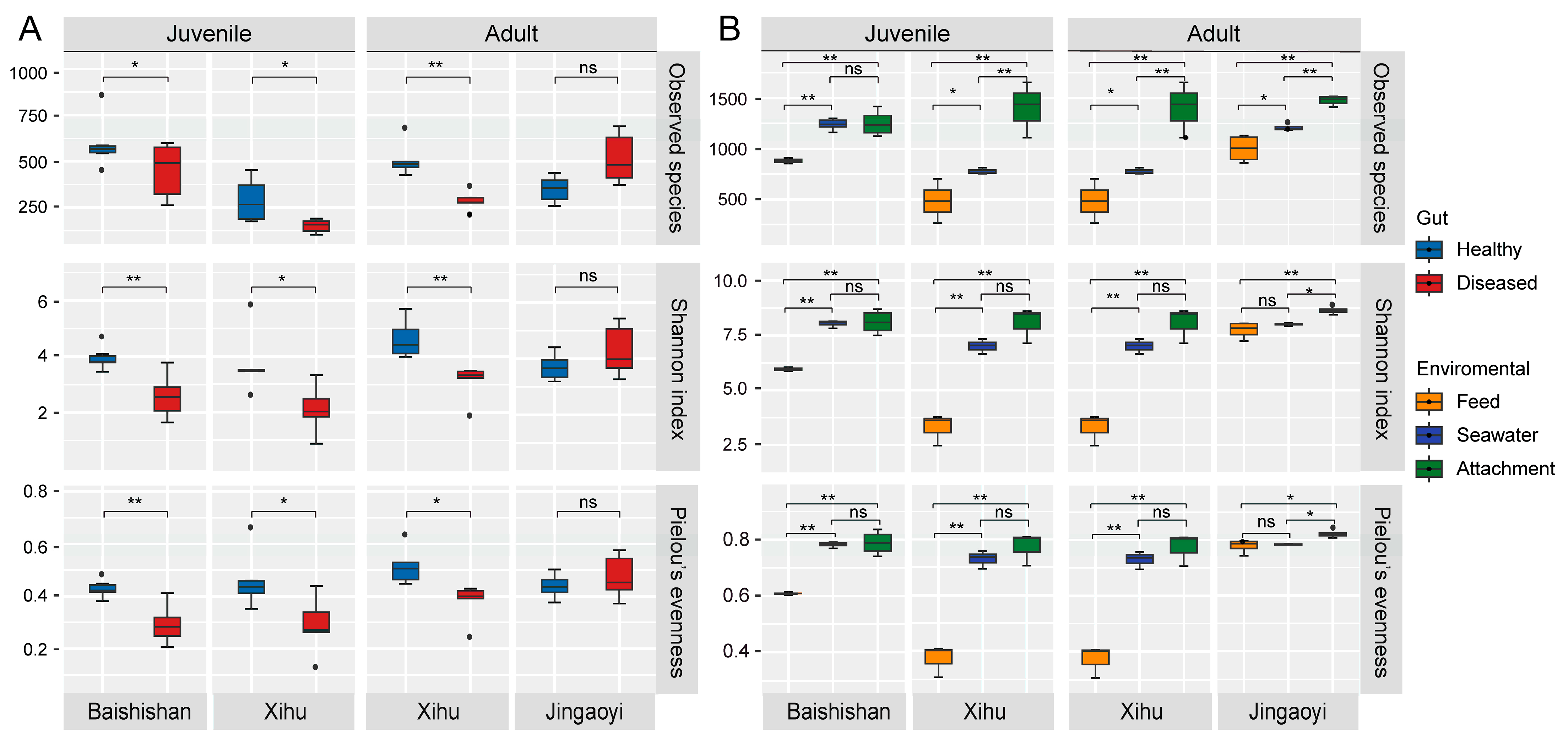

3.2. Alpha Diversity of Gut Microbiota in White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

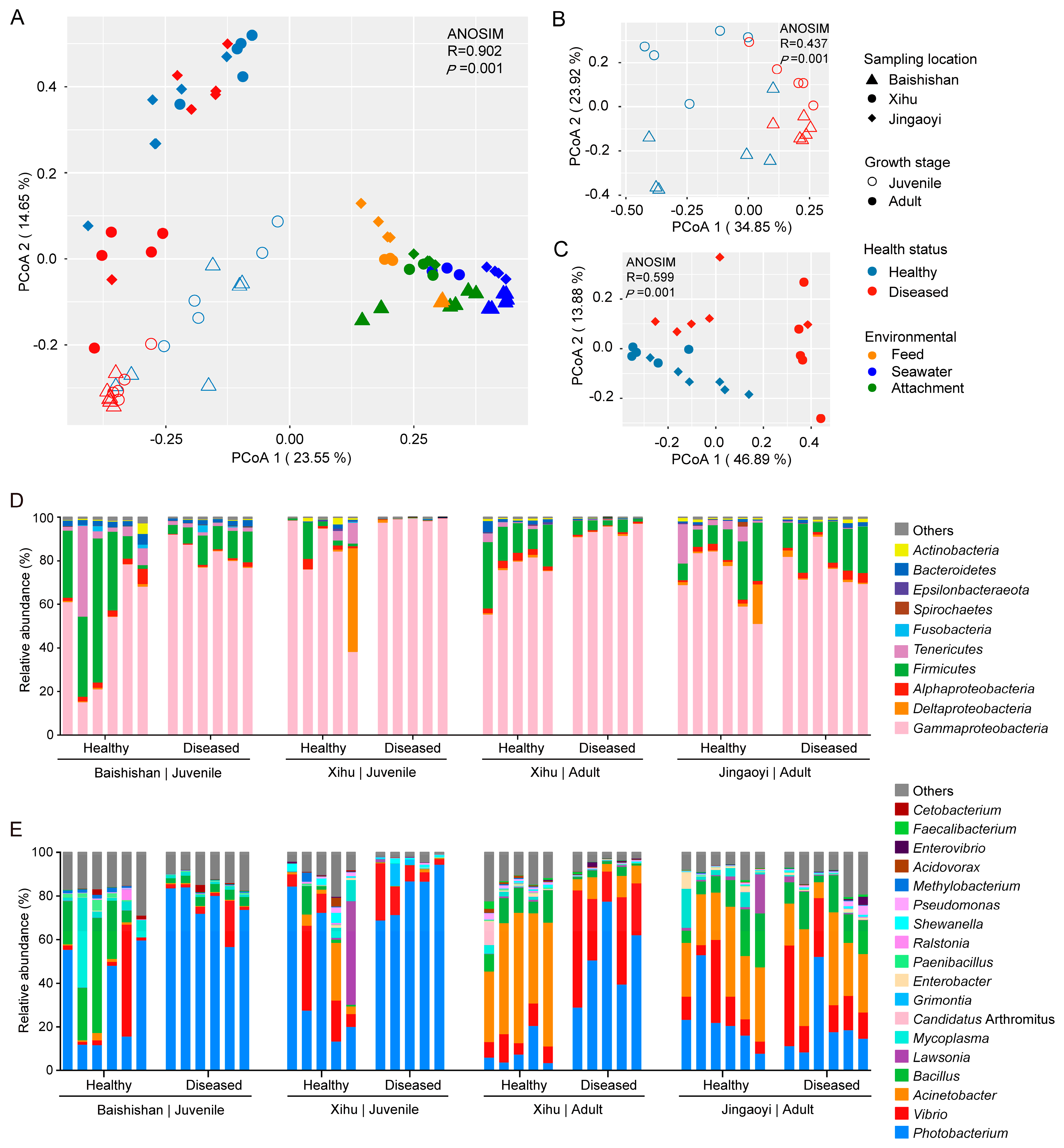

3.3. Compositional Variations in the Gut Microbiota Between Healthy and White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

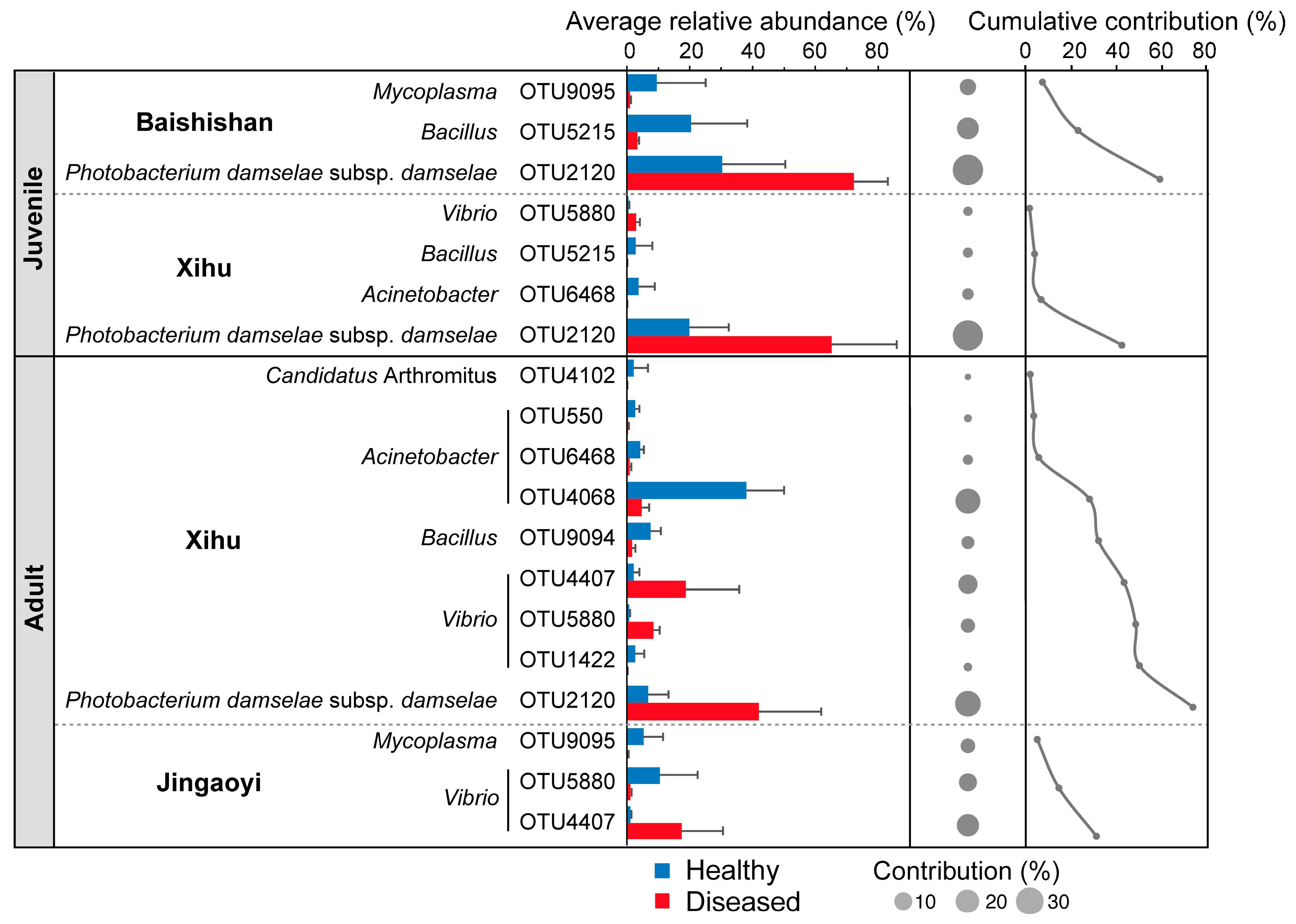

3.4. Differential Taxa in the Gut Microbiota Between Healthy and White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

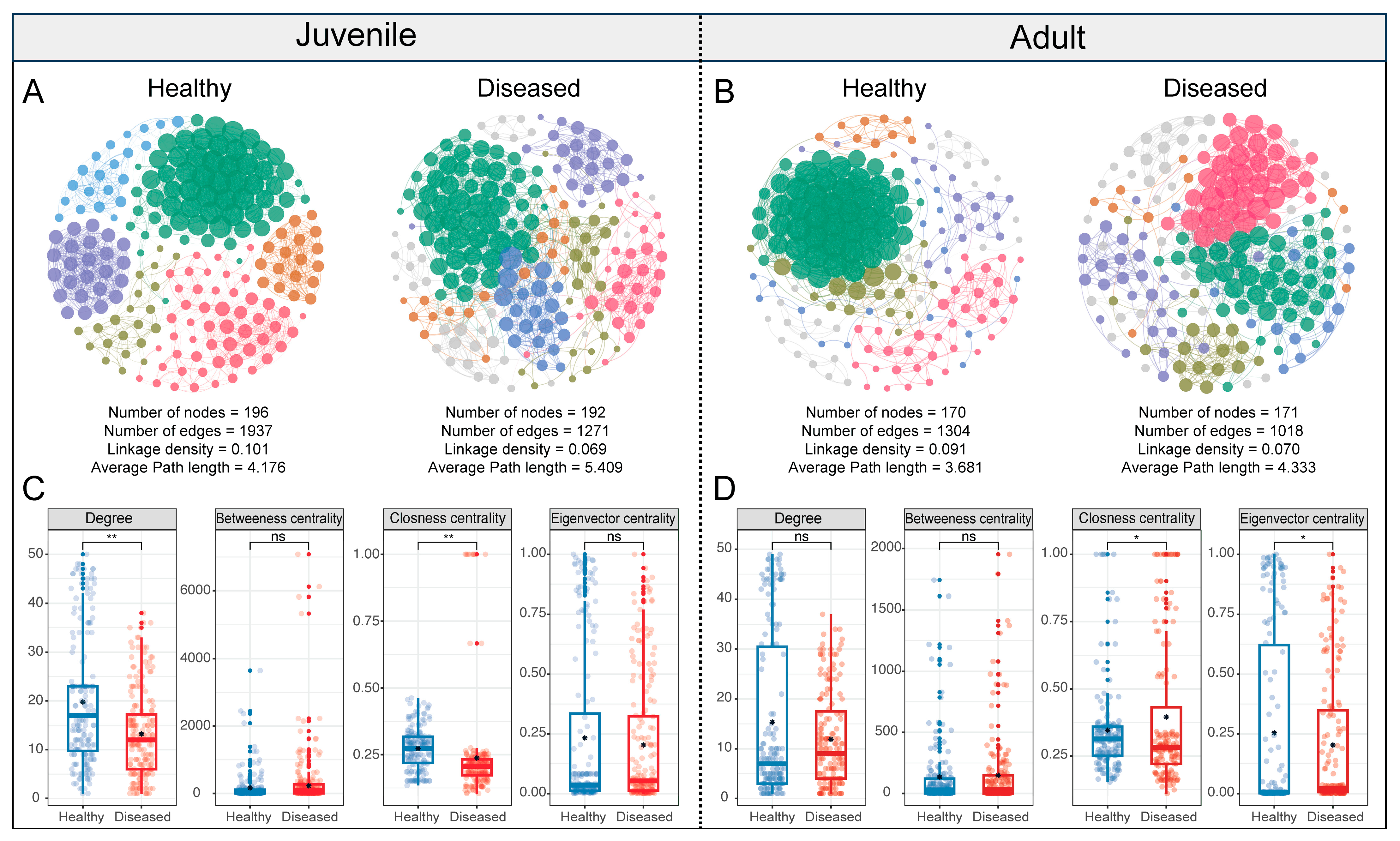

3.5. Co-Occurrence Network of Gut Microbiota in White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

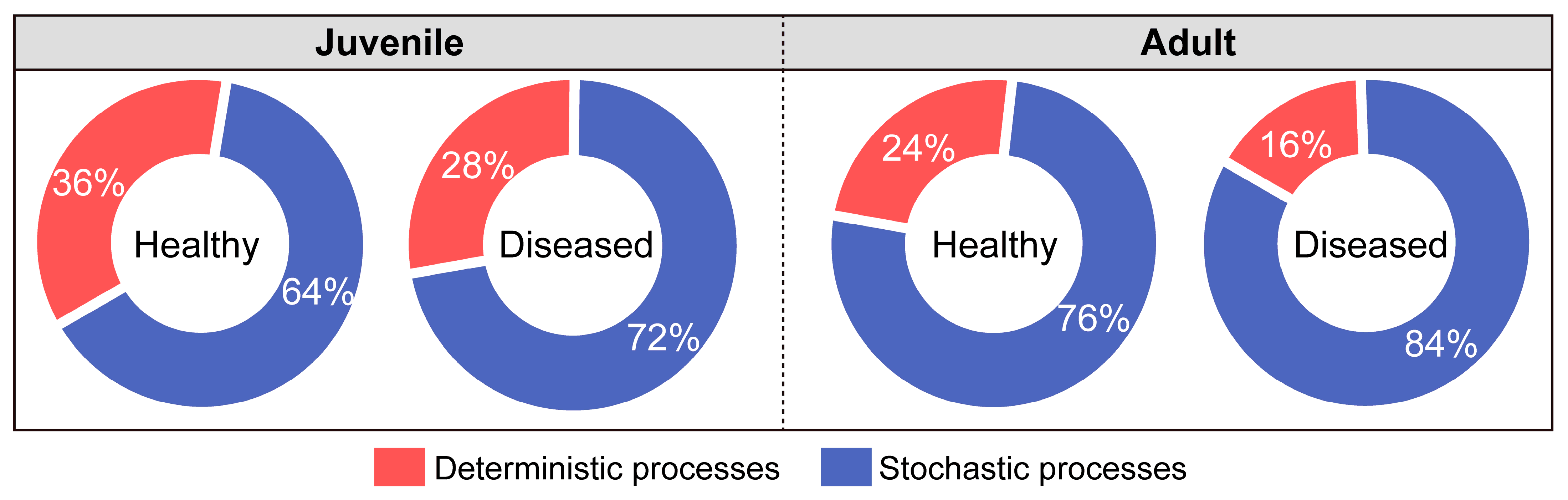

3.6. Assembly of Gut Microbiota in White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

4. Discussion

4.1. Reduced Diversity and Stability of the Gut Microbiota in White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

4.2. Microbial Imbalance Driven by P. damselae Proliferation and Bacillus Reduction in the Gut of White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

4.3. Enhanced Stochasticity in Gut Microbiota Assembly of White-Gill Diseased L. crocea

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, N.; Wang, C.; Xiao, S.; Huang, W.; Lin, M.; Yan, Q.; Ma, Y. Intestinal microbiota in large yellow croaker, Larimichthys crocea, at different ages. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2018, 49, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. China Fisheries Statistical Yearbook 2024; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Chen, S.; Su, Y.; Hong, W. Aquaculture of the Large Yellow Croaker. In Aquaculture in China; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, R.; Ji, J.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, B.; et al. The study of the genomic selection of white gill disease resistance in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Aquaculture 2023, 574, 739682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wen, L.; Xin, Z.; Wang, G.; Lin, H.; Wang, H.; Wei, B.; Yan, X.; Wang, W.; Guo, B. Research on the histopathology of Larimichthys crocea affected by white gill disease and analysis of its bacterial and viral community characteristics. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 161, 110287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Xie, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, G.; He, J.; Xu, W. Preliminary study of a new virus pathogen that caused the white-gill disease in cultured Larimichthys crocea. J. Fish. China 2017, 41, 1455–1463. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. PCR detection of cage cultured large yellow croaker Iridovirus in the Luoyuan bay, Fujian province. Fujian J. Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 2013, 35, 5–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.J.; Qin, Z.D.; Shi, H.; Jiang, N.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.L.; Xie, J.J.; Wang, G.S.; Wang, W.M.; Asim, M.; et al. Mass mortality associated with a viral-induced anaemia in cage-reared large yellow croaker, Larimichthys crocea (Richardson). J. Fish Dis. 2015, 38, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Chen, Z.; Ding, H.; Xie, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, G.; He, J.; Xu, W. Preliminary study on the histopathology and detection methods of a Myxosporea parasite that causes white-gill disease in cultured Larimichthys crocea. J. Fish. Sci. China 2019, 26, 203–213. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, D.; Stentiford, G.D.; Wang, H.-C.; Koskella, B.; Tyler, C.R. The pathobiome in animal and plant diseases. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Albina, E.; Citti, C.; Cosson, J.F.; Jacques, M.A.; Lebrun, M.H.; Le Loir, Y.; Ogliastro, M.; Petit, M.A.; Roumagnac, P.; et al. Shifting the paradigm from pathogens to pathobiome: New concepts in the light of meta-omics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, L.P.; Shen, Y.Q. A systematic review of advances in intestinal microflora of fish. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peatman, E.; Lange, M.; Zhao, H.; Beck, B.H. Physiology and immunology of mucosal barriers in catfish (Ictalurus spp.). Tissue Barriers 2015, 3, e1068907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Long, M.; Ji, C.; Shen, Z.; Gatesoupe, F.J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Alterations of the gut microbiome of largemouth bronze gudgeon (Coreius guichenoti) suffering from furunculosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, H.; Gatesoupe, F.J.; She, R.; Lin, Q.; Yan, X.; Li, J.; Li, X. Bacterial signatures of “red-operculum” disease in the gut of crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Li, H.W.; Wu, W.; Zhang, M.; Guo, J.; Deng, X.Y.; Wang, F.; Lin, L.B. The response of microbiota community to Streptococcus agalactiae infection in zebrafish intestine. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlechte, J.; Skalosky, I.; Geuking, M.B.; McDonald, B. Long-distance relationships-regulation of systemic host defense against infections by the gut microbiota. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiome and health: Mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4516–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Pena, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Updating the 97% identity threshold for 16S ribosomal RNA OTUs. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2371–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Spakowicz, D.J.; Hong, B.-Y.; Petersen, L.M.; Demkowicz, P.; Chen, L.; Leopold, S.R.; Hanson, B.M.; Agresta, H.O.; Gerstein, M.; et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Simpson, G.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package, R Package Version 2.5-3. 2018. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Deutschmann, I.M.; Delage, E.; Giner, C.R.; Sebastián, M.; Poulain, J.; Arístegui, J.; Duarte, C.M.; Acinas, S.G.; Massana, R.; Gasol, J.M.; et al. Disentangling microbial networks across pelagic zones in the tropical and subtropical global ocean. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, H.; Dsouza, M.; Lou, J.; He, Y.; Dai, Z.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J.; Gilbert, J.A. Geographic patterns of co-occurrence network topological features for soil microbiota at continental scale in eastern China. ISME J. 2016, 10, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E., Jr.; Dupont, C. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous, R Package Version 4.6-0. 2021. Available online: https://hbiostat.org/R/Hmisc (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Csárdi, G.; Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal Complex Syst. 2006, 1695, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stegen, J.C.; Lin, X.; Konopka, A.E.; Fredrickson, J.K. Stochastic and deterministic assembly processes in subsurface microbial communities. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembel, S.W.; Cowan, P.D.; Helmus, M.R.; Cornwell, W.K.; Morlon, H.; Ackerly, D.D.; Blomberg, S.P.; Webb, C.O. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.Z.; Ning, D.L. Stochastic community assembly: Does it matter in microbial ecology? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, e00002-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegen, J.C.; Lin, X.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Chen, X.; Kennedy, D.W.; Murray, C.J.; Rockhold, M.L.; Konopka, A. Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them. ISME J. 2013, 7, 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegen, J.C.; Lin, X.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Konopka, A.E. Estimating and mapping ecological processes influencing microbial community assembly. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, F.; Bäckhed, F. The gut microbiota—Masters of host development and physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Flores, G.; Pickard, J.M.; Núñez, G. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance: Mechanisms and regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, H. The microbiota: A crucial mediator in gut homeostasis and colonization resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1417864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, G.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Intestinal microbiota of healthy and unhealthy Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L. in a recirculating aquaculture system. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2017, 36, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Qi, P.; Chang, X.; Chang, Z. Effects of dechlorane plus on intestinal barrier function and intestinal microbiota of Cyprinus carpio L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 204, 111124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parshukov, A.N.; Kashinskaya, E.N.; Simonov, E.P.; Hlunov, O.V.; Izvekova, G.I.; Andree, K.B.; Solovyev, M.M. Variations of the intestinal gut microbiota of farmed rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), depending on the infection status of the fish. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, T.A.; Naeem, S.; Howe, K.M.; Knops, J.M.H.; Tilman, D.; Reich, P. Biodiversity as a barrier to ecological invasion. Nature 2002, 417, 636–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, C.A.; Elsas, J.D.v.; Salles, J.F. Microbial invasions: The process, patterns, and mechanisms. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, R.L.; Volkoff, H. Gut Microbiota and energy homeostasis in fish. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streb, L.-M.; Cholewińska, P.; Gschwendtner, S.; Geist, J.; Rath, S.; Schloter, M. Age matters: Exploring differential effects of antimicrobial treatment on gut microbiota of adult and juvenile brown trout (Salmo trutta). Anim. Microbiome 2025, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Yang, K.; Huang, L.; Huang, X.; Qiuqian, L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, D. Disease outbreak accompanies the dispersive structure of shrimp gut bacterial community with a simple core microbiota. AMB Express 2018, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schryver, P.; Vadstein, O. Ecological theory as a foundation to control pathogenic invasion in aquaculture. ISME J. 2014, 8, 2360–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Jin, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, D. Strain-specific changes in the gut microbiota profiles of the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei in response to cold stress. Aquaculture 2019, 503, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Zhou, Q.J.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, J. Interplay between the gut microbiota and immune responses of ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis) during Vibrio anguillarum infection. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2017, 68, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, K.; Raes, J. Microbial interactions: From networks to models. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Xiang, J.; Xiong, F.; Wang, G.; Zou, H.; Li, W.; Li, M.; Wu, S. Effects of Bacillus licheniformis on the growth, antioxidant capacity, intestinal barrier and disease resistance of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Fish Shellfish Immun. 2020, 97, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, H.; Tong, T.; Tong, W.; Dong, L.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z. Dietary supplementation of Bacillus subtilis and fructooligosaccharide enhance the growth, non-specific immunity of juvenile ovate pompano, Trachinotus ovatus and its disease resistance against Vibrio vulnificus. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2014, 38, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuebutornye, F.; Abarike, E.D.; Lu, Y. A review on the application of Bacillus as probiotics in aquaculture. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2019, 87, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Weng, G.; Zheng, Z. The intestinal bacterial community of healthy and diseased animals and its association with the aquaculture environment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, A.J.; Lemos, M.L.; Osorio, C.R. Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, a bacterium pathogenic for marine animals and humans. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terceti, M.S.; Rivas, A.J.; Alvarez, L.; Noia, M.; Cava, F.; Osorio, C.R. rstB regulates expression of the Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae major virulence factors damselysin, phobalysin P and phobalysin C. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouz, B.; Toranzo, A.E.; Milán, M.; Amaro, C. Evidence that water transmits the disease caused by the fish pathogen Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 88, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.-x.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.-g.; Jiang, Y.; Liao, M.-j.; Rong, X.-j. First report of skin ulceration caused by Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae in net-cage cultured black rockfish (Sebastes schlegeli). Aquaculture 2019, 503, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanza, X.M.; Osorio, C.R.; Proença, D. Transcriptome changes in response to temperature in the fish pathogen Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae: Clues to understand the emergence of disease outbreaks at increased seawater temperatures. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0210118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, A.Y.; Taranto, M.P.; Gerez, C.L.; Agriopoulou, S.; Smaoui, S.; Varzakas, T.; Enshasy, H.A.E. Recent advances in the understanding of stress resistance mechanisms in probiotics: Relevance for the design of functional food systems. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, C.A.; Fuhrman, J.A.; Horner-Devine, M.C.; Martiny, J.B. Beyond biogeographic patterns: Processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellend, M. Conceptual synthesis in community ecology. Q. Rev. Biol. 2010, 85, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dai, W.; Qiu, Q.; Dong, C.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, J. Contrasting ecological processes and functional compositions between intestinal bacterial community in healthy and diseased shrimp. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 72, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, D.; Deng, Y.; Tiedje, J.M.; Zhou, J. A general framework for quantitatively assessing ecological stochasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 16892–16898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Rawls, J.F. Intestinal microbiota composition in fishes is influenced by host ecology and environment. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 3100–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Refaey, M.M.; Xu, W.; Tang, R.; Li, L. Host age affects the development of southern catfish gut bacterial community divergent from that in the food and rearing water. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Zhu, W.; Yu, Y.; He, Z.; Wu, B.; Wang, C.; Shu, L.; Li, X.; Yin, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Host development overwhelms environmental dispersal in governing the ecological succession of zebrafish gut microbiota. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; He, Z.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; Kempher, M.L.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liao, L.; et al. Environmental filtering decreases with fish development for the assembly of gut microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 4739–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, P.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, D. Gastrointestinal microbiota imbalance is triggered by the enrichment of Vibrio in subadult Litopenaeus vannamei with acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zeng, S.; Xiong, J.; Hou, D.; Zhou, R.; Xing, C.; Wei, D.; Deng, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, H.; et al. Microecological Koch’s postulates reveal that intestinal microbiota dysbiosis contributes to shrimp white feces syndrome. Microbiome 2020, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, D.; Shen, W.; Hou, D. Microbial Imbalance and Stochastic Assembly Drive Gut Dysbiosis in White-Gill Diseased Larimichthys crocea (Richardson, 1846). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122737

Wang X, Cheng H, Liu T, Wang X, Wu X, Yu J, Zhang D, Shen W, Hou D. Microbial Imbalance and Stochastic Assembly Drive Gut Dysbiosis in White-Gill Diseased Larimichthys crocea (Richardson, 1846). Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122737

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xuan, Huangwei Cheng, Ting Liu, Xuelei Wang, Xiongfei Wu, Junqi Yu, Demin Zhang, Weiliang Shen, and Dandi Hou. 2025. "Microbial Imbalance and Stochastic Assembly Drive Gut Dysbiosis in White-Gill Diseased Larimichthys crocea (Richardson, 1846)" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122737

APA StyleWang, X., Cheng, H., Liu, T., Wang, X., Wu, X., Yu, J., Zhang, D., Shen, W., & Hou, D. (2025). Microbial Imbalance and Stochastic Assembly Drive Gut Dysbiosis in White-Gill Diseased Larimichthys crocea (Richardson, 1846). Microorganisms, 13(12), 2737. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122737