Effects of Endophytic Fungi and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Microbial Community Function and Metabolic Pathways in the Rhizosphere Soil of Festuca rubra

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Nutritional Characteristics of F. rubra and Determination of Rhizosphere Soil Enzyme Activity

2.3. DNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Metagenomic Sequencing

2.4. Sequence Quality Control and Genome Assembly

2.5. Gene Prediction, Taxonomic Analysis, Functional Annotation, and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

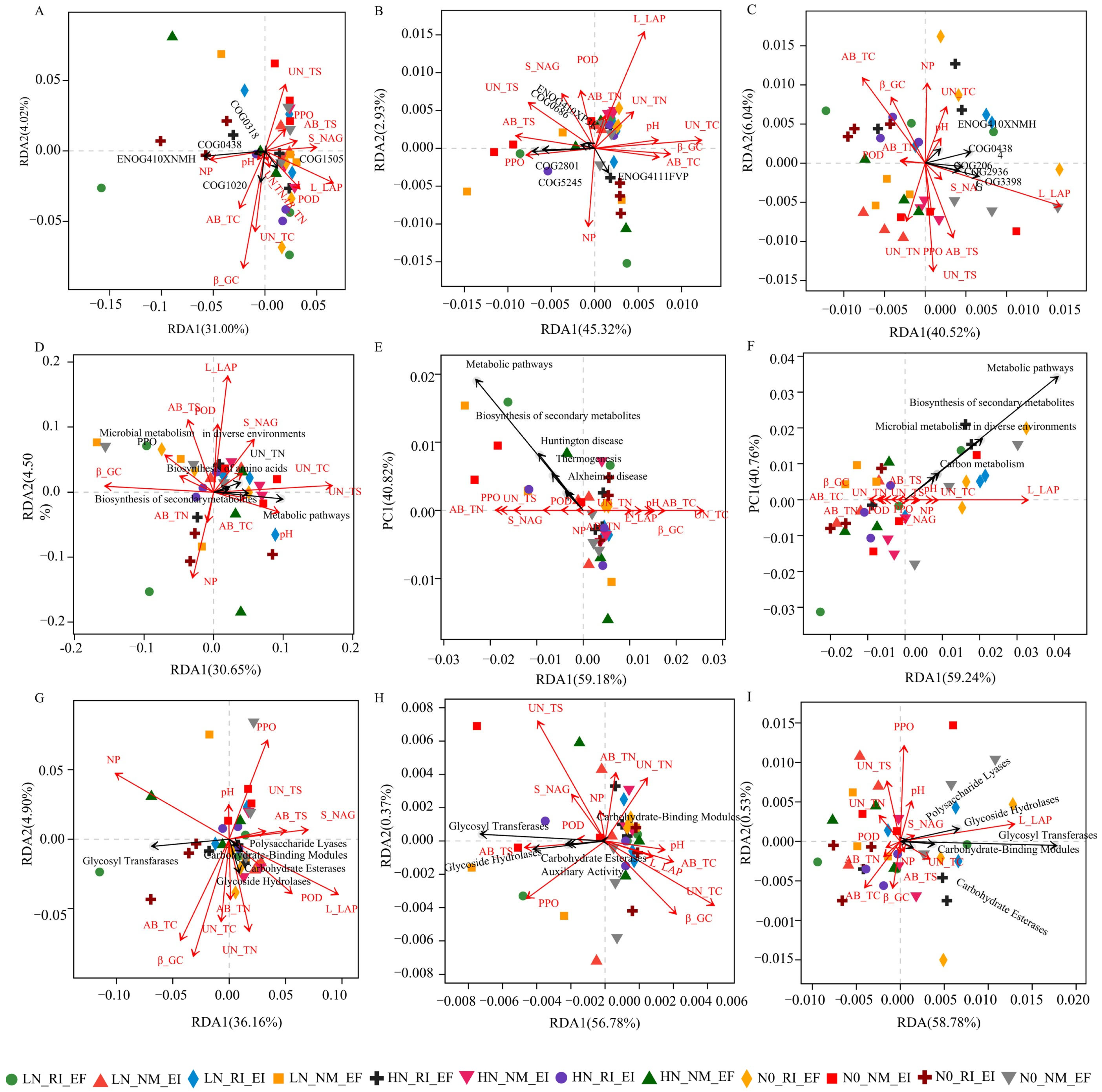

3.1. Driving Factors of Soil Microbial Communities in the Rhizosphere of F. rubra

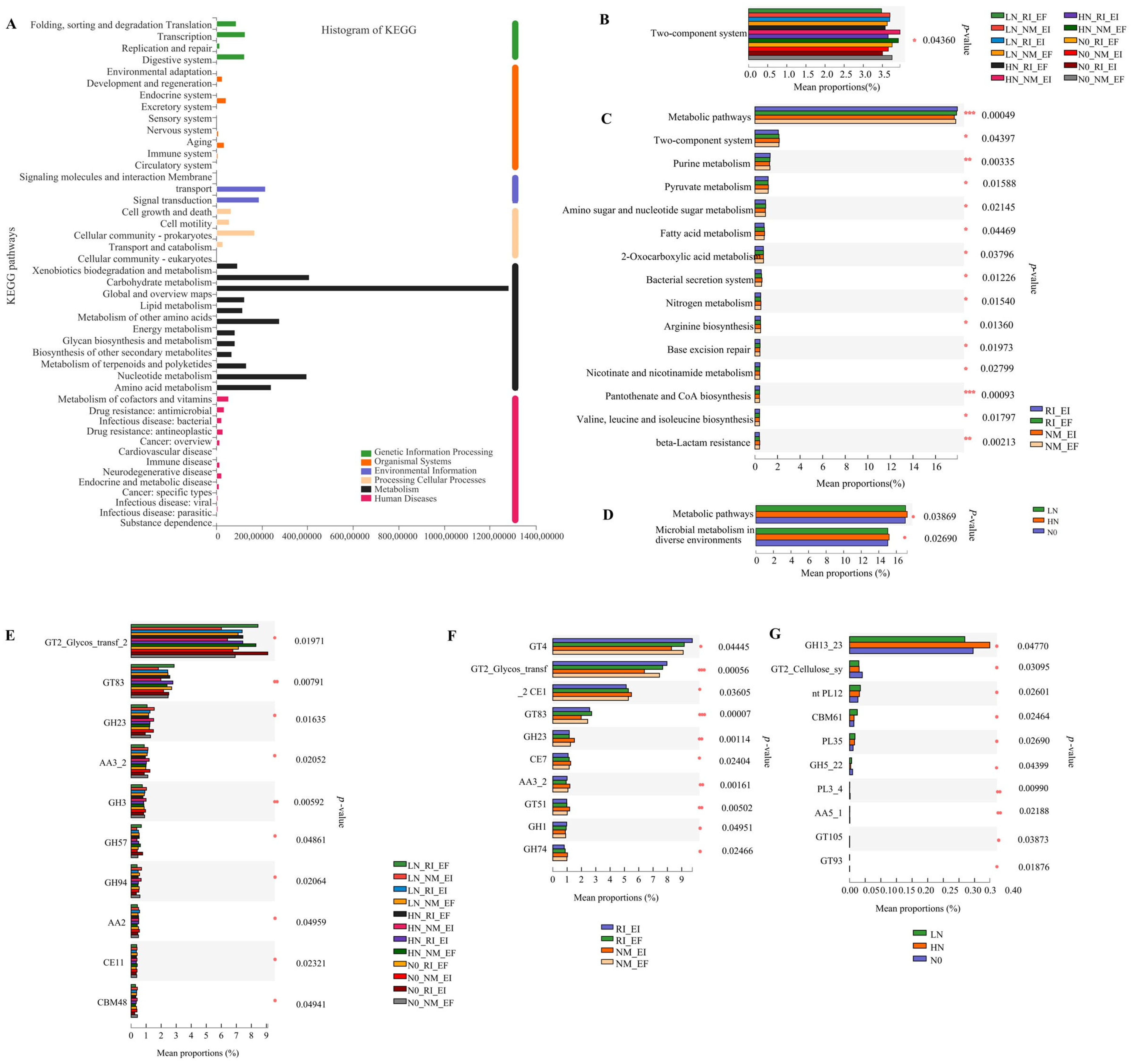

3.2. Functional Contributions and Metabolic Pathways of Different Groups of Soil Microbial Communities in the Rhizosphere of F. rubra

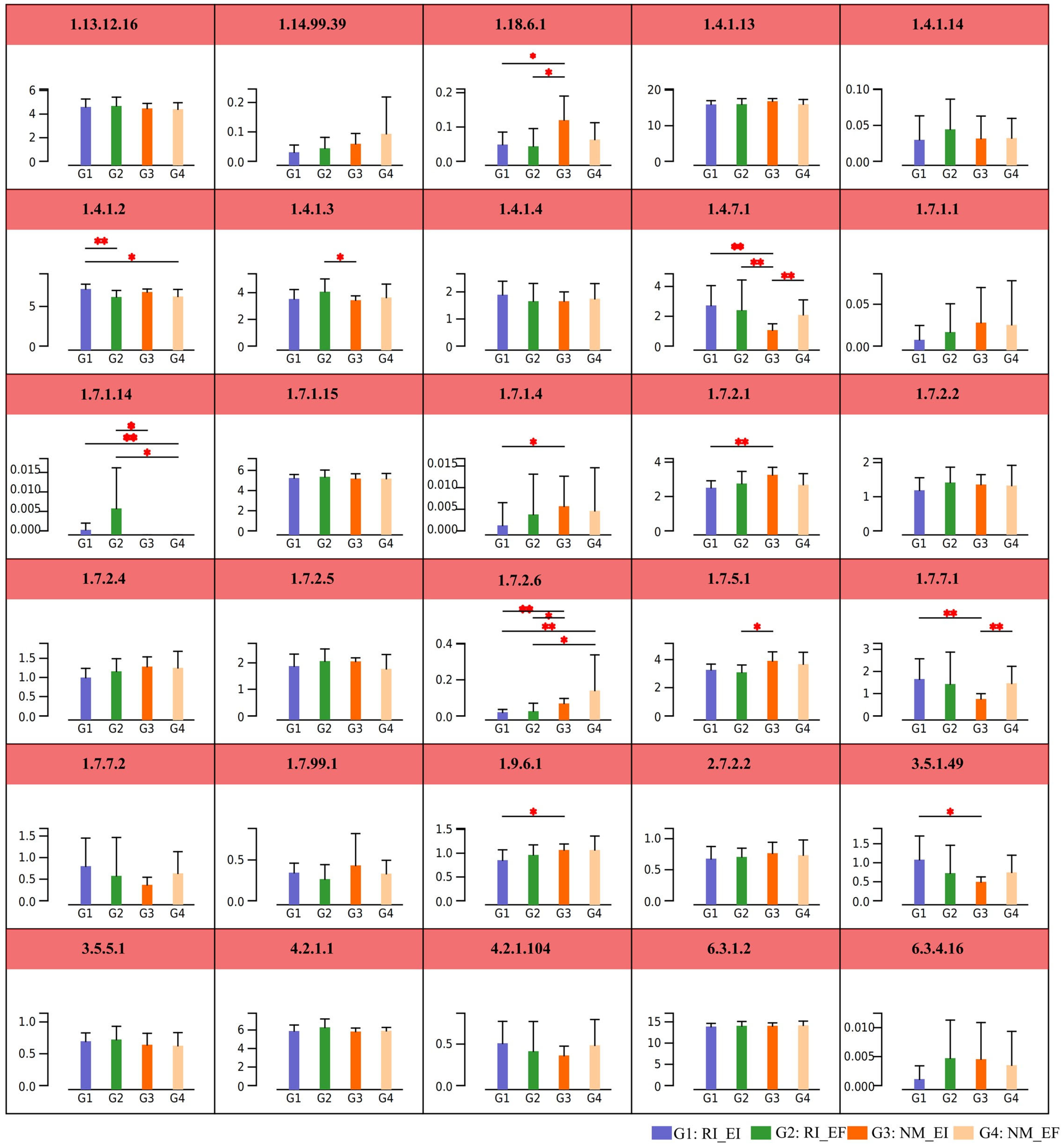

3.3. The Metabolism Pathways of Soil Microbial Communities in the Rhizosphere of F. rubra

4. Discussion

4.1. Functions and Factors Influencing the Soil Microbial Communities in the Rhizosphere of F. rubra

4.2. Relationships Between Microbial Community Diversity and Function in the Rhizosphere Soil of F. rubra

4.3. Effects of Endophytic Fungi and AMF Colonization on the Metabolic Pathways of the F. rubra Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Community

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, W.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, K.; Xing, J.; Song, Y. The Complex Co-Occurrence Network under N Deposition Resulting in the Change of Soil Bacterial Structure and the Decrease of Bacterial Abundance in Subtropical Quercus Aquifolioides Forest. Forests 2025, 16, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.; Bai, H.; Jin, L.; Wang, B.-T.; Ruan, H.-H.; Mao, L.; Jin, F.-J.; et al. Effects of Nitrogen Addition on Rhizospheric Soil Microbial Communities of Poplar Plantations at Different Ages. For. Ecol. Manage. 2021, 494, 119328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Wang, Q.; Xing, Y. Research Progress on the Effects of Nitrogen Addition on Soil and Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure. Int. J. Ecol. 2022, 11, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.E.; Maynard, Z.; Gilbert, G.S.; Coley, P.D.; Kursar, T.A. Are Tropical Fungal Endophytes Hyperdiverse? Ecol. Lett. 2000, 3, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, X.; Guo, J.; Leff, J.W.; McNear, D.H.; Fierer, N.; McCulley, R.L. Infection with a Shoot-Specific Fungal Endophyte (Epichloë) Alters Tall Fescue Soil Microbial Communities. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 72, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; McCulley, R.L.; McNear, D.H. Tall Fescue Cultivar and Fungal Endophyte Combinations Influence Plant Growth and Root Exudate Composition. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, J.; Siegrist, J.A.; Nelson, J.A.; McCulley, R.L. Fungal Endophyte Infection Increases Carbon Sequestration Potential of Southeastern USA Tall Fescue Stands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 44, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A. Fresh Perspectives on the Roles of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Plant Nutrition and Growth. Mycologia 2012, 104, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Xiao, Q.; Geng, X.; Lin, K.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, X. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Alter Rhizosphere Bacterial Diversity, Network Stability and Function of Lettuce in Barren Soil. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 323, 112533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelin, H.; Devi, T.S.; Gupta, S.; Kapoor, R. Mitigation of Salinity Stress in Plants by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis: Current Understanding and New Challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, S.; Schauster, A.; Liao, H.-L.; Ruytinx, J. Mechanisms of Stress Tolerance and Their Effects on the Ecology and Evolution of Mycorrhizal Fungi. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 2158–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changey, F.; Meglouli, H.; Fontaine, J.; Magnin-Robert, M.; Tisserant, B.; Lerch, T.Z.; Lounès-Hadj Sahraoui, A. Initial Microbial Status Modulates Mycorrhizal Inoculation Effect on Rhizosphere Microbial Communities. Mycorrhiza 2019, 29, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducousso-Détrez, A.; Raveau, R.; Fontaine, J.; Hijri, M.; Lounès-Hadj Sahraoui, A. Glomerales Dominate Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Communities Associated with Spontaneous Plants in Phosphate-Rich Soils of Former Rock Phosphate Mining Sites. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, Z.; Yang, X.; Sheng, L.; Mao, H.; Zhu, S. Metagenomics Reveal Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Altering Functional Gene Expression of Rhizosphere Microbial Community to Enhance Iris Tectorum’s Resistance to Cr Stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 895, 164970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Pan, S.; He, P.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Sun, Y. Effects of Pioneer Plants Richness on Community Characteristics of Vegetation and Their Soil and Water Conservation Benefit for Highway Side Slope. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2015, 35, 3653–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Liang, X.; Guo, T.; Chai, B. Impact of Nutrients on Protozoa Community Diversity and Structure in Litter of Two Natural Grass Species in a Copper Tailings Dam, China. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D.; Chen, G.-L.; LoCascio, P.F.; Land, M.L.; Larimer, F.W.; Hauser, L.J. Prodigal: Prokaryotic Gene Recognition and Translation Initiation Site Identification. BMC Bioinf. 2010, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, H.; Park, J.; Takagi, T. MetaGene: Prokaryotic Gene Finding from Environmental Genome Shotgun Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 5623–5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Niu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, S.; Li, W. CD-HIT: Accelerated for Clustering the next-Generation Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3150–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Li, Y.; Kristiansen, K.; Wang, J. SOAP: Short Oligonucleotide Alignment Program. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 713–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and Sensitive Protein Alignment Using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, C.; Li, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, Z. Different Techniques Reveal the Difference of Community Structure and Function of Fungi from Root and Rhizosphere of Salvia Miltiorrhiza Bunge. Plant Biol. 2023, 25, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourna, M.; Maclean, P.; Condron, L.; O’Callaghan, M.; Wakelin, S.A. Links between Sulphur Oxidation and Sulphur-Oxidising Bacteria Abundance and Diversity in Soil Microcosms Based on soxB Functional Gene Analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 88, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerwonka, G.; Konieczna, I.; Żarnowiec, P.; Zieliński, A.; Malinowska-Gniewosz, A.; Gałuszka, A.; Migaszewski, Z.; Kaca, W. Characterization of Microbial Communities in Acidified, Sulfur Containing Soils. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2017, 66, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Qu, X. Soil Depth Exerts a Stronger Impact on Microbial Communities and the Sulfur Biological Cycle than Salinity in Salinized Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 164898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lu, Y.; Ye, X.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Chen, E. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Cadmium Stress Response Induced by Exogenous Sulfur in Tartary Buckwheat. Biotechnol. Bull. 2023, 39, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zeng, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, L. Study on the Coupling Mechanism Between Soil Bacterial Community Diversity and Ecosystem Multifunctionality in Intensive Citrus Cultivation Systems. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2025, 62, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H.; Fraga, R. Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria and Their Role in Plant Growth Promotion. Biotechnol. Adv. 1999, 17, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenberger, G.; Frey, S.D.; Six, J.; Paustian, K.; Elliott, E.T. Bacterial and Fungal Cell-wall Residues in Conventional and No-tillage Agroecosystems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, S.D.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Bacterial and Fungal Abundance and Biomass in Conventional and No-Tillage Agroecosystems along Two Climatic Gradients. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999, 31, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, C.; Cássio, F. Contribution of Fungi and Bacteria to Leaf Litter Decomposition in a Polluted River. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5266–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Feller, C.; Denef, K.; Ogle, S.; de Moraes Sa, J.C.; Albrecht, A. Soil Organic Matter, Biota and Aggregation in Temperate and Tropical Soils—Effects of No-Tillage. Agronomie 2002, 22, 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, D.J.; Firestone, M.K.; Nuccio, E.; Hodge, A. Interactions between an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus and a Soil Microbial Community Mediating Litter Decomposition. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 80, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuccio, E.E.; Hodge, A.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Herman, D.J.; Weber, P.K.; Firestone, M.K. An Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Significantly Modifies the Soil Bacterial Community and Nitrogen Cycling during Litter Decomposition. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 1870–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, H. Positive correlation Between Soil Bacterial Metabolic and Plant Species Diversity and Bacterial and fungal Diversity in a Vegetation Succession on Karst. Plant Soil 2008, 307, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheublin, T.R.; Sanders, I.R.; Keel, C.; Van Der Meer, J.R. Characterisation of Microbial Communities Colonising the Hyphal Surfaces of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. ISME J. 2010, 4, 752–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enebe, M.C.; Babalola, O.O. Soil Fertilization Affects the Abundance and Distribution of Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling Genes in the Maize Rhizosphere. AMB Express 2021, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; He, L.; Jia, T. Effects of Endophytic Fungi and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Microbial Community Function and Metabolic Pathways in the Rhizosphere Soil of Festuca rubra. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2735. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122735

Luo Z, Zhou Y, Wang X, He L, Jia T. Effects of Endophytic Fungi and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Microbial Community Function and Metabolic Pathways in the Rhizosphere Soil of Festuca rubra. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2735. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122735

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Zhengming, Yanying Zhou, Xuerong Wang, Lei He, and Tong Jia. 2025. "Effects of Endophytic Fungi and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Microbial Community Function and Metabolic Pathways in the Rhizosphere Soil of Festuca rubra" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2735. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122735

APA StyleLuo, Z., Zhou, Y., Wang, X., He, L., & Jia, T. (2025). Effects of Endophytic Fungi and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Microbial Community Function and Metabolic Pathways in the Rhizosphere Soil of Festuca rubra. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2735. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122735