The Gut Microbiome in Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Sjögren’s Disease: Correlations with Dry Eye

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Clinical Assessment

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Fecal Microbiome Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Data

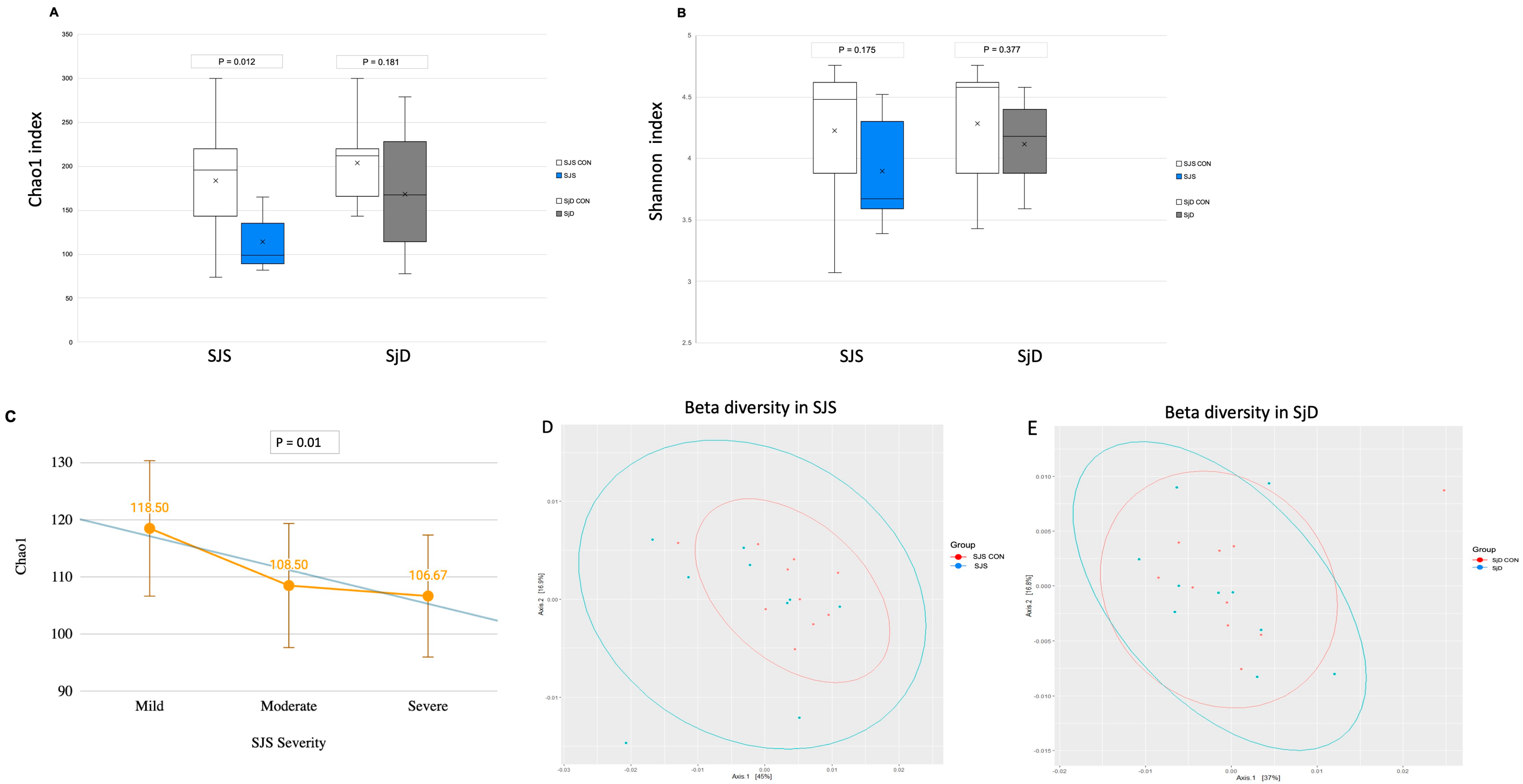

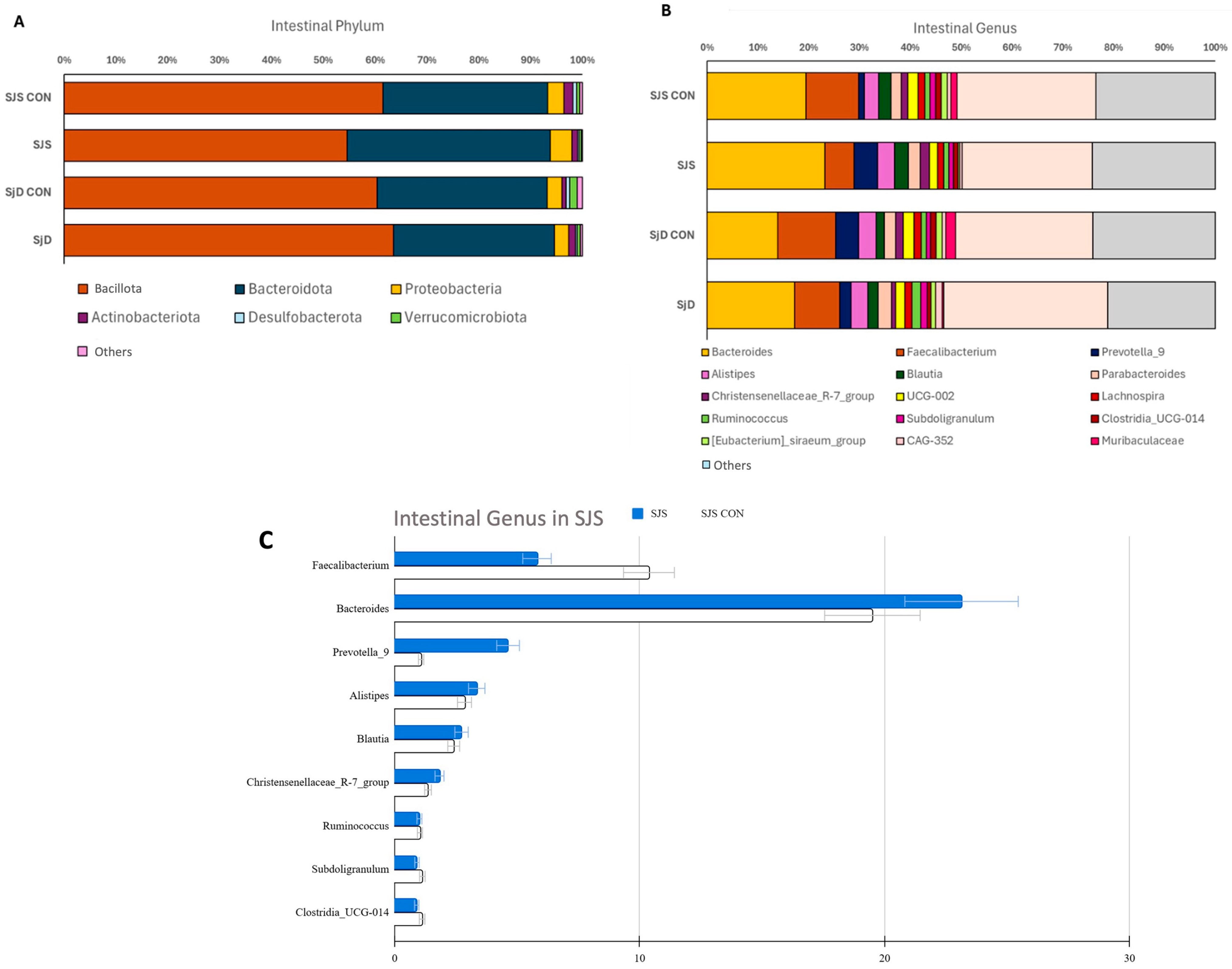

3.2. Intestinal Microbiome Measures

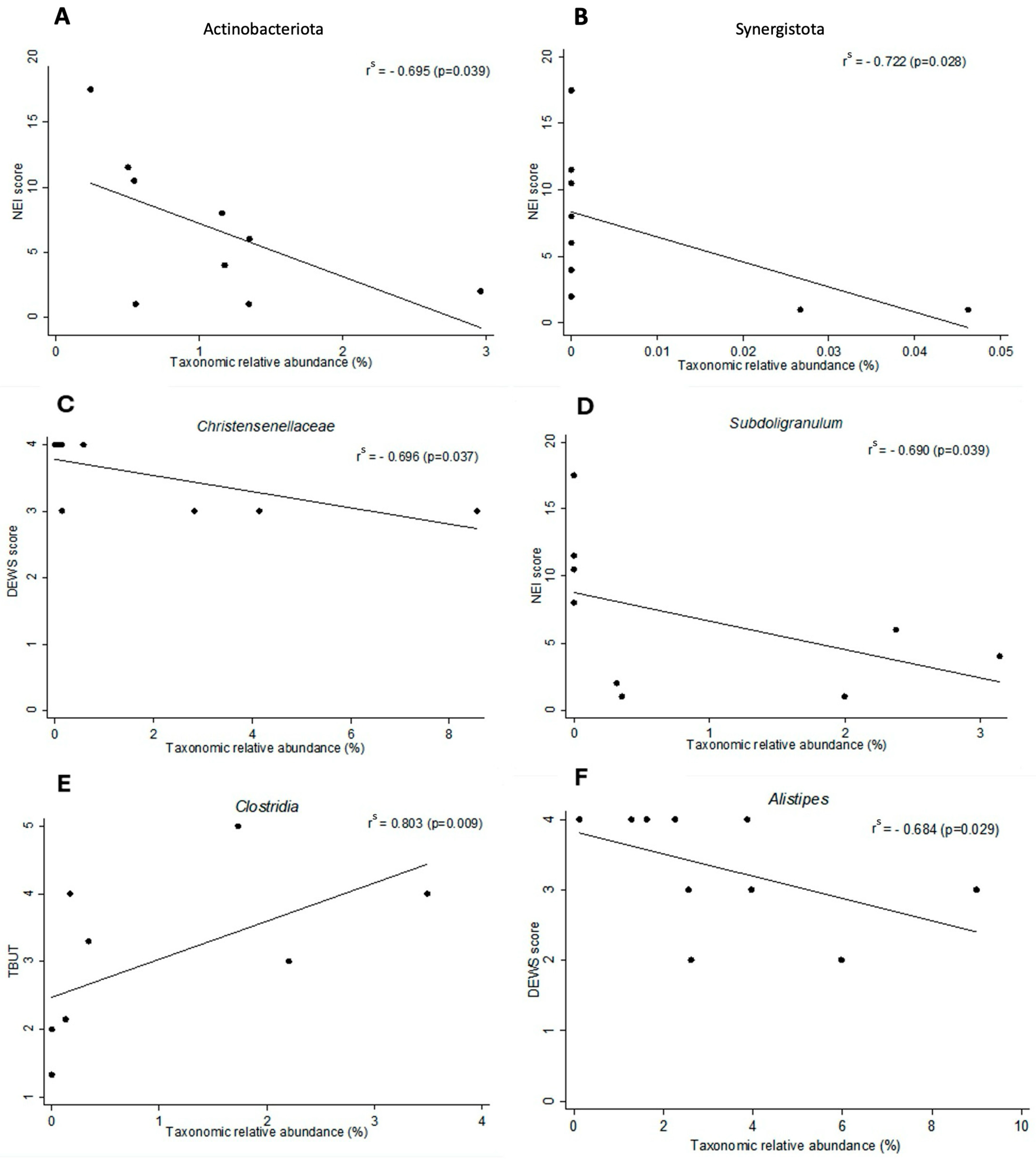

3.3. Dry Eye Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Human Microbiome Project Consortium. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 2012, 486, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aagaard, K.; Petrosino, J.; Keitel, W.; Watson, M.; Katancik, J.; Garcia, N.; Patel, S.; Cutting, M.; Madden, T.; Hamilton, H.; et al. The Human Microbiome Project strategy for comprehensive sampling of the human microbiome and why it matters. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 1012–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Horai, R.; Mattapallil, M.J.; Ajami, N.J.; Wong, M.; Petrosino, J.F.; Itoh, K.; Chan, C.-C.; Caspi, R.R. Gut microbiota as a source of a surrogate antigen that triggers autoimmunity in an immune-privileged site. Gut Microbes. 2017, 8, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, C.; Schaefer, L.; Bian, F.; Yu, Z.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; de Paiva, C.S. Dysbiosis Modulates Ocular Surface Inflammatory Response to Liposaccharide. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 4224–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Campagnoli, L.I.M.; Varesi, A.; Barbieri, A.; Marchesi, N.; Pascale, A. Targeting the Gut-Eye Axis: An Emerging Strategy to Face Ocular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trujillo-Vargas, C.M.; Schaefer, L.; Alam, J.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; de Paiva, C.S. The gut-eye-lacrimal gland-microbiome axis in Sjögren Syndrome. Ocul. Surf. 2020, 18, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kohanim, S.; Palioura, S.; Saeed, H.N.; Akpek, E.K.; Amescua, G.; Basu, S.; Blomquist, P.H.; Bouchard, C.S.; Dart, J.K.; Gai, X.; et al. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis—A Comprehensive Review and Guide to Therapy. I. Systemic Disease. Ocul. Surf. 2016, 14, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueta, M. Pathogenesis of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis with Severe Ocular Complications. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 651247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ueta, M.; Sotozono, C.; Inatomi, T.; Kojima, K.; Tashiro, K.; Hamuro, J.; Kinoshita, S. Toll-like receptor 3 gene polymorphisms in Japanese patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mariette, X.; A Criswell, L.A. Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Baer, A.N.; Brito-Zerón, M.d.P.; Hammitt, K.M.; Bouillot, C.; Retamozo, S.; Mackey, A.; Yarowsky, D.; Turner, B.; Blanck, J.; et al. 2023 International Rome consensus for the nomenclature of Sjögren disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2025, 21, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paiva, C.S.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Mechanisms of Disease in Sjögren Syndrome-New Developments and Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Craig, J.P.; Nichols, K.K.; Akpek, E.K.; Caffery, B.; Dua, H.S.; Joo, C.-K.; Liu, Z.; Nelson, J.D.; Nichols, J.J.; Tsubota, K.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugfelder, S.C.; de Paiva, C.S. The Pathophysiology of Dry Eye Disease: What We Know and Future Directions for Research. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, S4–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Paiva, C.S.; Jones, D.B.; Stern, M.E.; Bian, F.; Moore, Q.L.; Corbiere, S.; Streckfus, C.F.; Hutchinson, D.S.; Ajami, N.J.; Petrosino, J.F.; et al. Altered Mucosal Microbiome Diversity and Disease Severity in Sjögren Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zaheer, M.; Wang, C.; Bian, F.; Yu, Z.; Hernandez, H.; de Souza, R.G.; Simmons, K.T.; Schady, D.; Swennes, A.G.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; et al. Protective role of commensal bacteria in Sjögren Syndrome. J. Autoimmun. 2018, 93, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schaefer, L.; Trujillo-Vargas, C.M.; Midani, F.S.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; de Paiva, C.S. Gut Microbiota from Sjögren syndrome Patients Decreased T Regulatory Cells in the Lymphoid Organs and Desiccation-Induced Corneal Barrier Disruption in Mice. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 852918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moon, J.; Choi, S.H.; Yoon, C.H.; Kim, M.K. Gut dysbiosis is prevailing in Sjögren’s syndrome and is related to dry eye severity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mendez, R.; Watane, A.; Farhangi, M.; Cavuoto, K.M.; Leith, T.; Budree, S.; Galor, A.; Banerjee, S. Gut microbial dysbiosis in individuals with Sjögren’s syndrome. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frizon, L.; Araújo, M.C.; Andrade, L.; Yu, M.C.Z.; Wakamatsu, T.H.; Höfling-Lima, A.L.; Gomes, J.Á.P. Evaluation of conjunctival bacterial flora in patients with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Clinics 2014, 69, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kittipibul, T.; Puangsricharern, V.; Chatsuwan, T. Comparison of the ocular microbiome between chronic Stevens-Johnson syndrome patients and healthy subjects. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh, S.; Maity, M.; Shanbhag, S.; Arunasri, K.; Basu, S. Lid Margin Microbiome in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Patients with Lid Margin Keratinization and Severe Dry Eye Disease. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2024, 65, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frizon, L.; Rocchetti, T.T.; Frizon, A.; de Alcântara, R.J.A.; Hofling-Lima, A.L.; de Paiva, C.S.; Gomes, J.Á.P. Ocular bacterial microbiome analysis by next-generation sequencing in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and Sjögren’s disease: Associations with dry eye indices. Exp. Eye. Res. 2025, 260, 110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotozono, C.; Ang, L.P.; Koizumi, N.; Higashihara, H.; Ueta, M.; Inatomi, T.; Yokoi, N.; Kaido, M.; Dogru, M.; Shimazaki, J.; et al. New grading system for the evaluation of chronic ocular manifestations in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. International Sjögren’s Syndrome Criteria Working Group. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- DEWS. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul. Surf. 2007, 5, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.T. The lacrimal secretory system and its treatment. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1966, 62, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bron, A.J.F.; Evans, V.E.B.; Smith, J.A. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea 2003, 22, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazantseva, J.; Malv, E.; Kaleda, A.; Kallastu, A.; Meikas, A. Optimisation of sample storage and DNA extraction for human gut microbiota studies. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Waste not, want not: Why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bussab, W.O.; Morettin, P.A. Estatística Básica, 10th ed.; Saraiva Educação: São Paulo, Brasil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Low, L.; Suleiman, K.; Shamdas, M.; Bassilious, K.; Poonit, N.; Rossiter, A.E.; Acharjee, A.; Loman, N.; Murray, P.I.; Wallace, G.R.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis in Ocular Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 780354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chakravarthy, S.K.; Jayasudha, R.; Prashanthi, G.S.; Ali, M.H.; Sharma, S.; Tyagi, M.; Shivaji, S. Dysbiosis in the Gut Bacterial Microbiome of Patients with Uveitis, an Inflammatory Disease of the Eye. Indian J. Microbiol. 2018, 58, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ye, Z.; Zhang, N.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Du, L.; Cao, Q.; Tang, J.; Zhou, C.; et al. A metagenomic study of the gut microbiome in Behcet’s disease. Microbiome 2018, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van der Meulen, T.A.; Harmsen, H.J.; Vila, A.V.; Kurilshikov, A.; Liefers, S.C.; Zhernakova, A.; Fu, J.; Wijmenga, C.; Weersma, R.K.; de Leeuw, K.; et al. Shared gut, but distinct oral microbiota composition in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Autoimmun. 2019, 97, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Ortiz, A.; Laborda-Illanes, A.; Plaza-Andrades, I.; del Pozo, A.M.; Cuadrado, A.V.; de Mora, M.R.C.; Leiva-Gea, I.; Sanchez-Alcoholado, L.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I. Connection between the Gut Microbiome, Systemic Inflammation, Gut Permeability and FOXP3 Expression in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, H.; Ji, S.; Chen, Z.; Cui, Z.; Chen, J.; Tang, S. Dysbiosis and Implication of the Gut Microbiota in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 646348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schaefer, L.; Hernandez, H.; Coats, R.A.; Yu, Z.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; de Paiva, C.S. Gut-derived butyrate suppresses ocular surface inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4512, Erratum in Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, W.; Doherty, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, H.; Li, W.; Wang, N.; Lei, G.; Zeng, C. Gut dysbiosis in rheumatic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 92 observational studies. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cao, Y.; Lu, H.; Xu, W.; Zhong, M. Gut microbiota and Sjögren’s syndrome: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1187906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Waters, J.L.; Ley, R.E. The human gut bacteria Christensenellaceae are widespread, heritable, and associated with health. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atarashi, K.; Tanoue, T.; Oshima, K.; Suda, W.; Nagano, Y.; Nishikawa, H.; Fukuda, S.; Saito, T.; Narushima, S.; Hase, K.; et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature 2013, 500, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lu, Y. Gut microbiota and derived metabolomic profiling in glaucoma with progressive neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 968992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jia, X.-M.; Wu, B.-X.; Chen, B.-D.; Li, K.-T.; Liu, Y.-D.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Compositional and functional aberrance of the gut microbiota in treatment-naïve patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Autoimmun. 2023, 141, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labetoulle, M.; Baudouin, C.; del Castillo, J.M.B.; Rolando, M.; Rescigno, M.; Messmer, E.M.; Aragona, P. How gut microbiota may impact ocular surface homeostasis and related disorders. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2024, 100, 101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Pang, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z.; Lu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Niu, M.; et al. Microbiota dysbiosis in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and the ameliorative effect of hydroxychloroquine. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chu, C.-Q. Gut Microbiota-Medication Interaction in Rheumatic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 796865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Zhang, S.; Silverman, G.; Li, M.; Cai, J.; Niu, H. Protective effect of hydroxychloroquine on rheumatoid arthritis-associated atherosclerosis. Anim. Model Exp Med. 2019, 2, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ocular Feature | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eyelash abnormalities | Trichiasis or distichiasis involving less than half of the eyelid | Trichiasis or distichiasis involving more than half of the eyelid | Trichiasis or distichiasis involving the entire eyelid |

| Lid margin keratinization | Continuous keratinization up to one-third of the eyelid | Continuous keratinization from one-third to one-half of the eyelid | Continuous keratinization involving more than half of the eyelid |

| Conjunctival inflammation | Conjunctival hyperemia up to ++ | Conjunctival hyperemia +++ | Conjunctival hyperemia ++++ |

| Conjunctival fibrosis | Conjunctival scarring up to the fornix shortening | Symblepharon without restriction of mobility | Symblepharon with restricted ocular motility |

| Limbal stem cell deficiency | Up to 180° | Between 180° and 270° | More than 270° |

| Corneal epitheliopathy | Punctate keratopathy and epithelial erosions | Epithelial defect | Epithelial defect with stromal involvement |

| Corneal opacity | Mild haze | Moderate haze | Diffuse haze obscuring anterior chamber details |

| N, Subjects | Age, Mean, Years | Age, Range, Years | Female/Male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SJS controls | 10 | 40 | 18–54 | 8/2 |

| SJS | 9 | 37 | 24–65 | 6/3 |

| p value | 0.517 a | 0.628 b | ||

| SjD controls | 10 | 49 | 39–57 | 10/0 |

| SjD | 10 | 50 | 44–60 | 10/0 |

| p value | 0.492 a | 1 b |

| OSDI | Schirmer I Test | Tear Break-Up Time | NEI | DED DEWS Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | mm | Seconds | Score | (Number of Patients) | |

| SJS controls | 1.03 ± 2.02 | 32.20 ± 10.16 | 13.06 ± 2.34 | 0.25 ± 0.42 | 0 (10/10) |

| SJS | 48.26 ± 25.71 | 12.72 ± 13.14 | 2.98 ± 1.20 | 6.83 ± 5.60 | 3 (4/9) |

| 4 (5/9) | |||||

| p value | p < 0.001 a | p = 0.002 a | p < 0.001 a | p = 0.008 a | p < 0.001 b |

| SjD controls | 1.23± 2.00 | 32.00 ± 10.01 | 12.68 ± 2.26 | 0.25 ± 0.42 | 0 (10/10) |

| SjD | 41.13 ± 23.89 | 10.15 ± 11.78 | 6.27 ± 3.28 | 4.20 ± 3.19 | 3 (4/10) |

| 4 (6/10) | |||||

| p value | p < 0.001 a | p < 0.001 a | p < 0.001 a | p = 0.003 a | p < 0.001 b |

| Control (N = 10) | SJS (N = 9) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum—Abundance (%), Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | |||

| Actinobacteriota | 1.74 ± 1.59 (0.50 to 4.70) | 1.09 ± 0.81 (0.24 to 2.96) | 0.288 |

| Bacteroidota | 31.71 ± 9.85 (20.03 to 54.45) | 39.21 ± 13.79 (18.11 to 63.09) | 0.191 |

| Campylobacterota | 0.00 ± 0.01 (0.00 to 0.02) | 0.00 ± 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | 0.343 |

| Cyanobacteriota | 0.29 ± 0.35 (0.00 to 0.84) | 0.06 ± 0.13 (0.00 to 0.38) | 0.120 |

| Desulfobacterota | 0.68 ± 0.70 (0.00 to 2.46) | 0.36 ± 0.43 (0.00 to 1.27) | 0.305 |

| Elusimicrobiota | 0.04 ± 0.13 (0.00 to 0.41) | 0.00 ± 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | 0.343 |

| Euryarchaeota | 0.10 ± 0.16 (0.00 to 0.47) | 0.05 ± 0.08 (0.00 to 0.18) | 0.546 |

| Bacillota | 61.57 ± 10.51 (37.34 to 76.27) | 54.59 ± 13.45 (34.70 to 75.33) | 0.191 |

| Fusobacteriota | 0.00 ± 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | 0.05 ± 0.14 (0.00 to 0.41) | 0.126 |

| Proteobacteria | 3.14 ± 1.45 (0.93 to 4.97) | 4.14 ± 2.34 (1.59 to 8.54) | 0.462 |

| Synergistota | 0.04 ± 0.10 (0.00 to 0.31) | 0.01 ± 0.02 (0.00 to 0.05) | 0.636 |

| Thermoplasmatota | 0.06 ± 0.11 (0.00 to 0.26) | 0.01 ± 0.02 (0.00 to 0.06) | 0.252 |

| Verrucomicrobiota | 0.63 ± 0.68 (0.00 to 1.97) | 0.42 ± 0.63 (0.00 to 1.89) | 0.458 |

| Genus—Abundance (%), Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | |||

| Faecalibacterium | 10.38 ± 5.08 (1.17 to 16.63) | 5.81 ± 4.62 (0.00 to 12.65) | 0.048 |

| Prevotella_9 | 1.08 ± 3.20 (0.00 to 10.19) | 4.63 ± 9.52 (0.00 to 27.49) | 0.275 |

| Alistipes | 2.85 ± 2.27 (0.00 to 7.65) | 3.35 ± 2.91 (0.11 to 7.94) | 0.806 |

| Bacteroides | 19.50 ± 13.46 (8.02 to 53.07) | 23.14 ± 15.53 (1.16 to 51.24) | 0.514 |

| Blautia | 2.41 ± 1.81 (0.65 to 6.95) | 2.73 ± 1.96 (0.00 to 5.59) | 0.683 |

| Christensenellaceae | 1.36 ± 1.63 (0.00 to 4.86) | 1.83 ± 2.93 (0.00 to 8.56) | 0.870 |

| Clostridia_UCG-014 | 1.12 ± 1.14 (0.00 to 3.04) | 0.90 ± 1.27 (0.00 to 3.49) | 0.836 |

| Lachnospira | 1.34 ± 1.34 (0.00 to 3.88) | 1.21 ± 1.35 (0.00 to 3.64) | 0.901 |

| Parabacteroides | 1.97 ± 1.26 (0.67 to 4.57) | 2.24 ± 1.42 (0.84 to 4.86) | 0.462 |

| Ruminococcus | 1.03 ± 1.21 (0.00 to 2.68) | 1.01 ± 1.07 (0.00 to 2.90) | 0.933 |

| Subdoligranulum | 1.13 ± 0.95 (0.00 to 3.13) | 0.91 ± 1.24 (0.00 to 3.14) | 0.410 |

| UCG-002 | 1.94 ± 2.00 (0.00 to 5.95) | 1.64 ± 1.35 (0.00 to 3.26) | 0.967 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frizon, L.; Rocchetti, T.T.; Frizon, A.; de Alcântara, R.J.A.; de Paiva, C.S.; Gomes, J.Á.P. The Gut Microbiome in Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Sjögren’s Disease: Correlations with Dry Eye. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2730. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122730

Frizon L, Rocchetti TT, Frizon A, de Alcântara RJA, de Paiva CS, Gomes JÁP. The Gut Microbiome in Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Sjögren’s Disease: Correlations with Dry Eye. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2730. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122730

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrizon, Luciana, Talita Trevizani Rocchetti, André Frizon, Rafael Jorge Alves de Alcântara, Cintia S. de Paiva, and José Álvaro Pereira Gomes. 2025. "The Gut Microbiome in Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Sjögren’s Disease: Correlations with Dry Eye" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2730. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122730

APA StyleFrizon, L., Rocchetti, T. T., Frizon, A., de Alcântara, R. J. A., de Paiva, C. S., & Gomes, J. Á. P. (2025). The Gut Microbiome in Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Sjögren’s Disease: Correlations with Dry Eye. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2730. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122730