Mining Activities in Iron Ore Areas Have Altered the Diversity and Functional Structure of Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities in Three Crops

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Sample Collection

2.2. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.3. PCR Amplification and Detection

2.4. Library Preparation, Sequencing, and Data Processing

2.5. Noise Reduction and Species Annotation

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

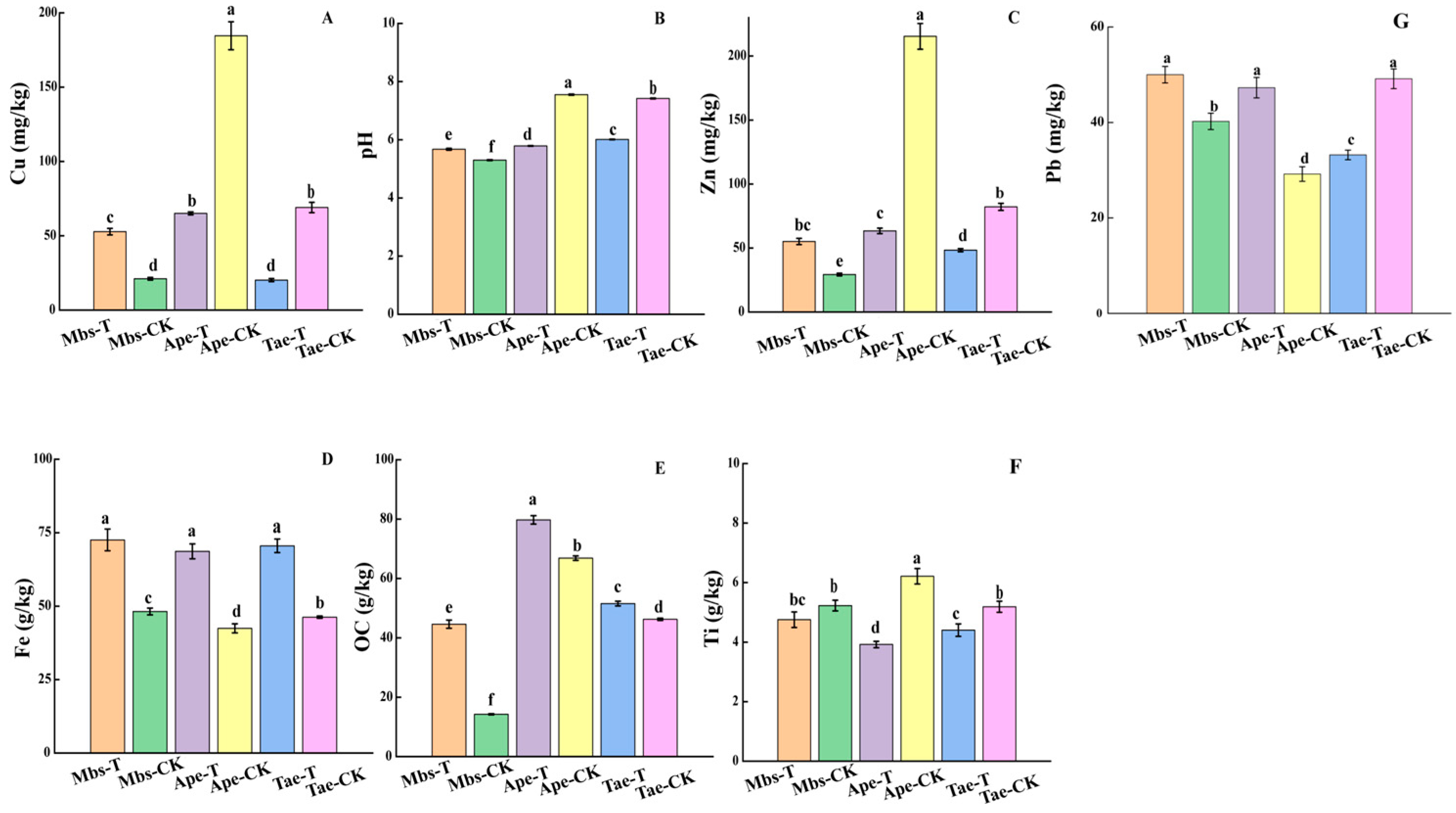

3.1. Determination and Physicochemical Analysis of Multiple Elements in the Rhizosphere Soil

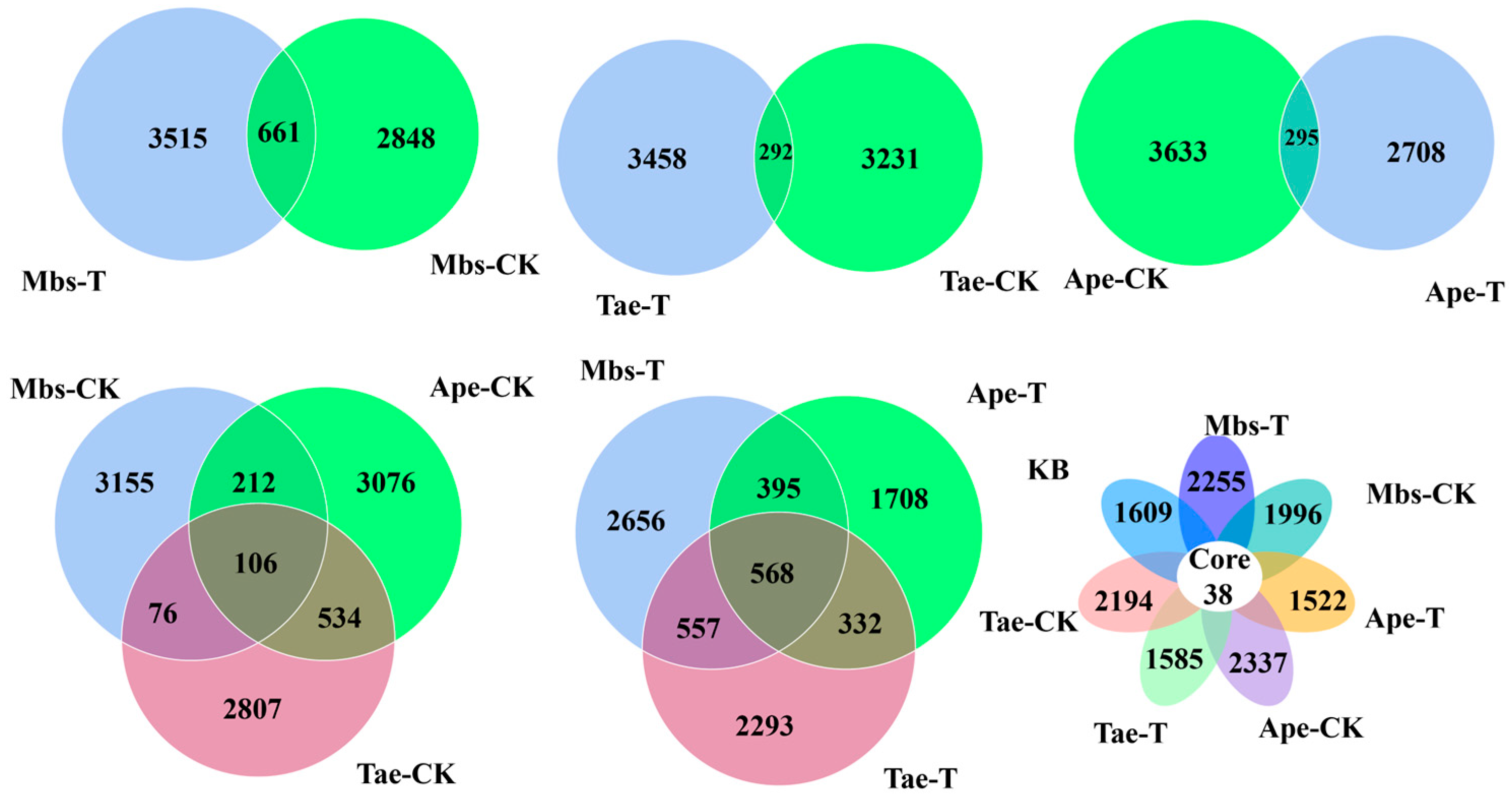

3.2. High-Throughput Sequencing Data Analysis

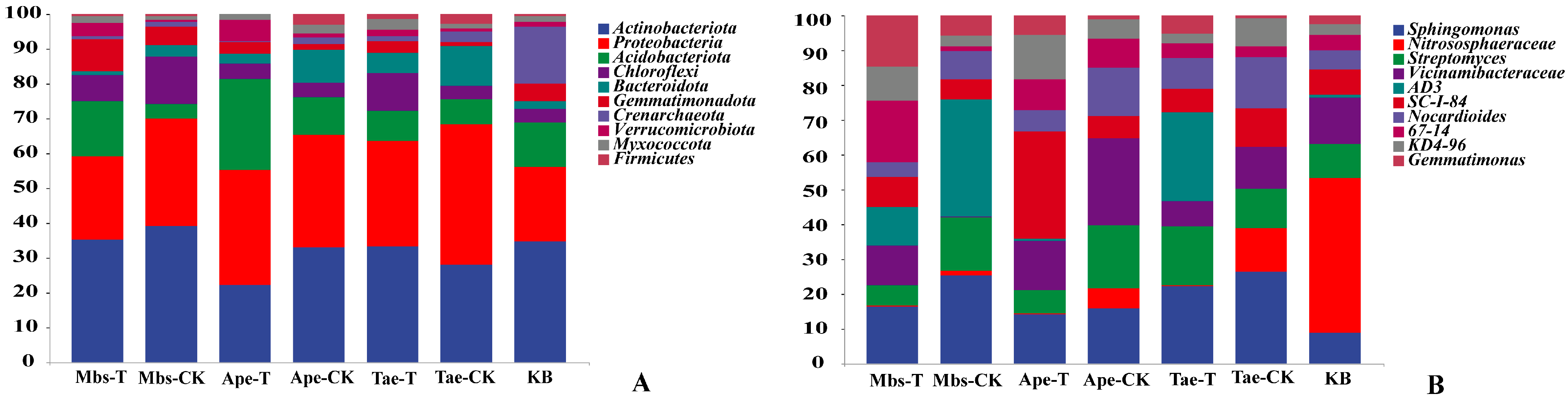

3.3. Microbial Community Composition

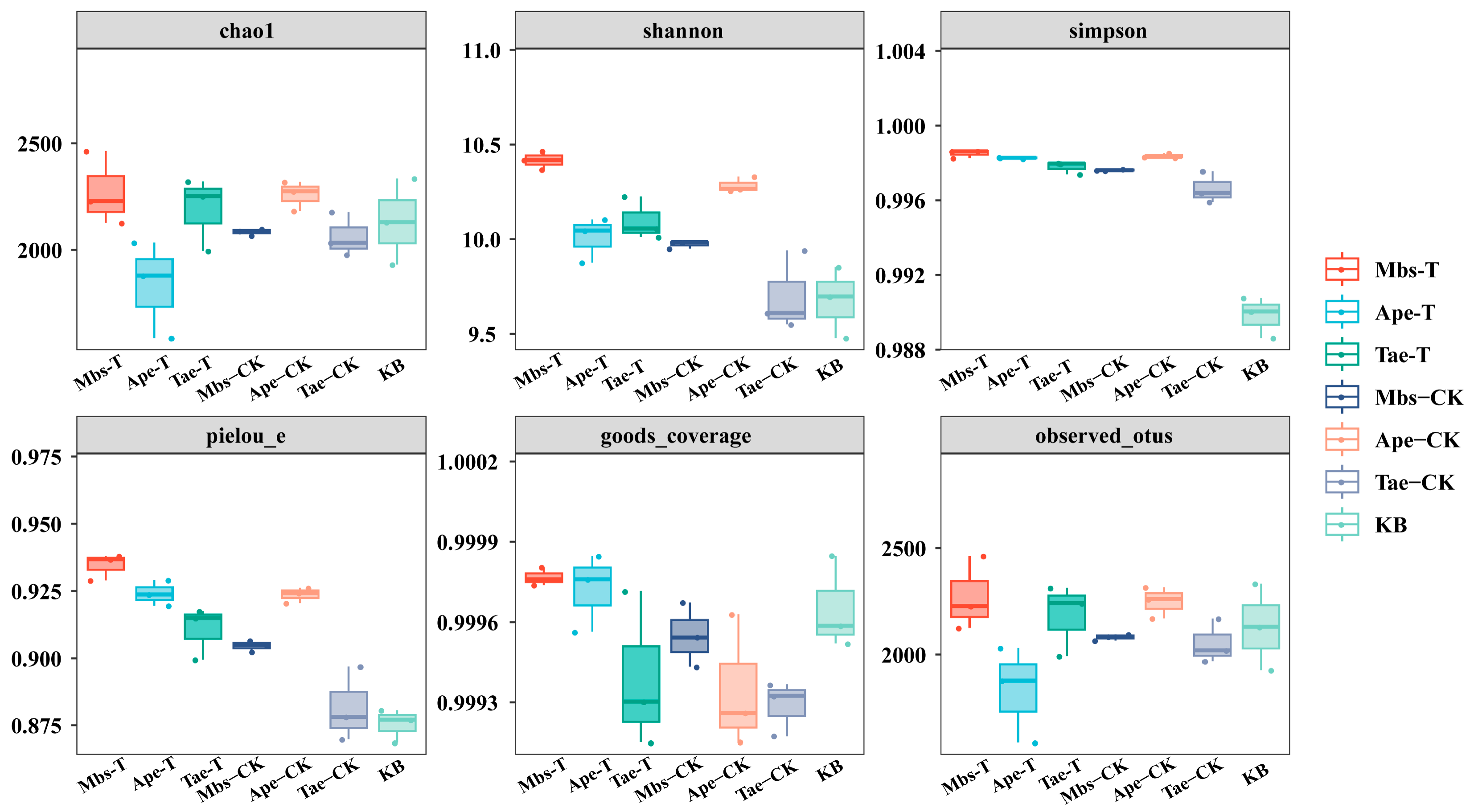

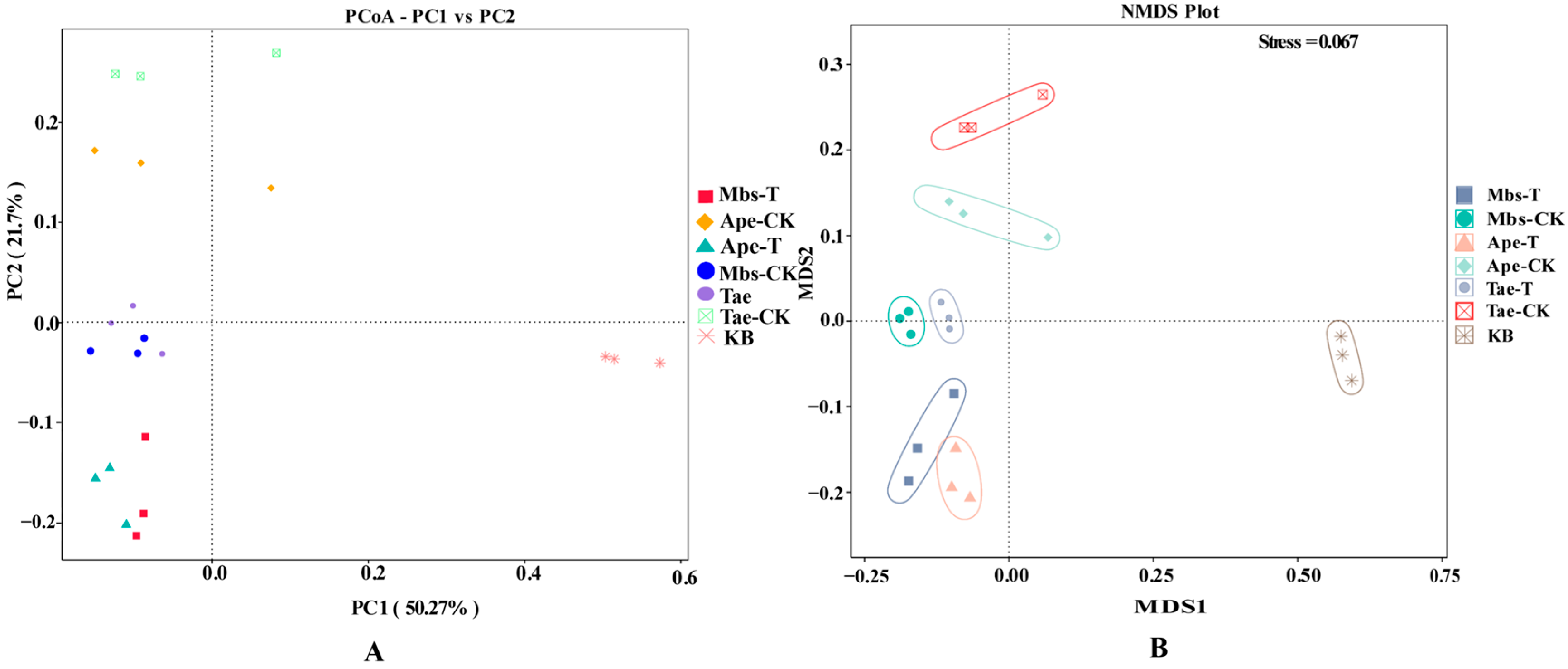

3.4. Analysis of Rhizobacterial Microbial Diversity

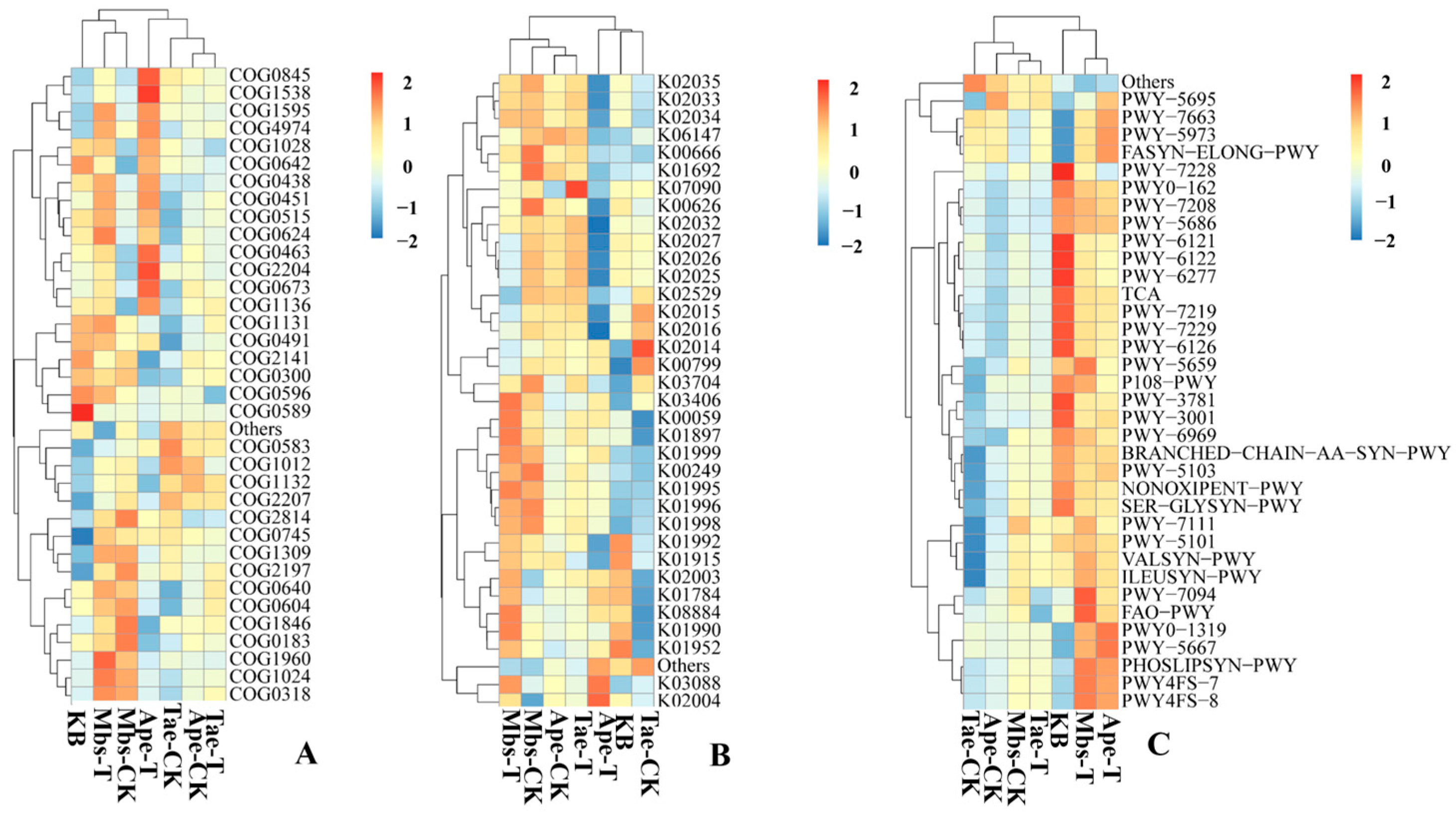

3.5. Prediction of Rhizosphere Microbial Function

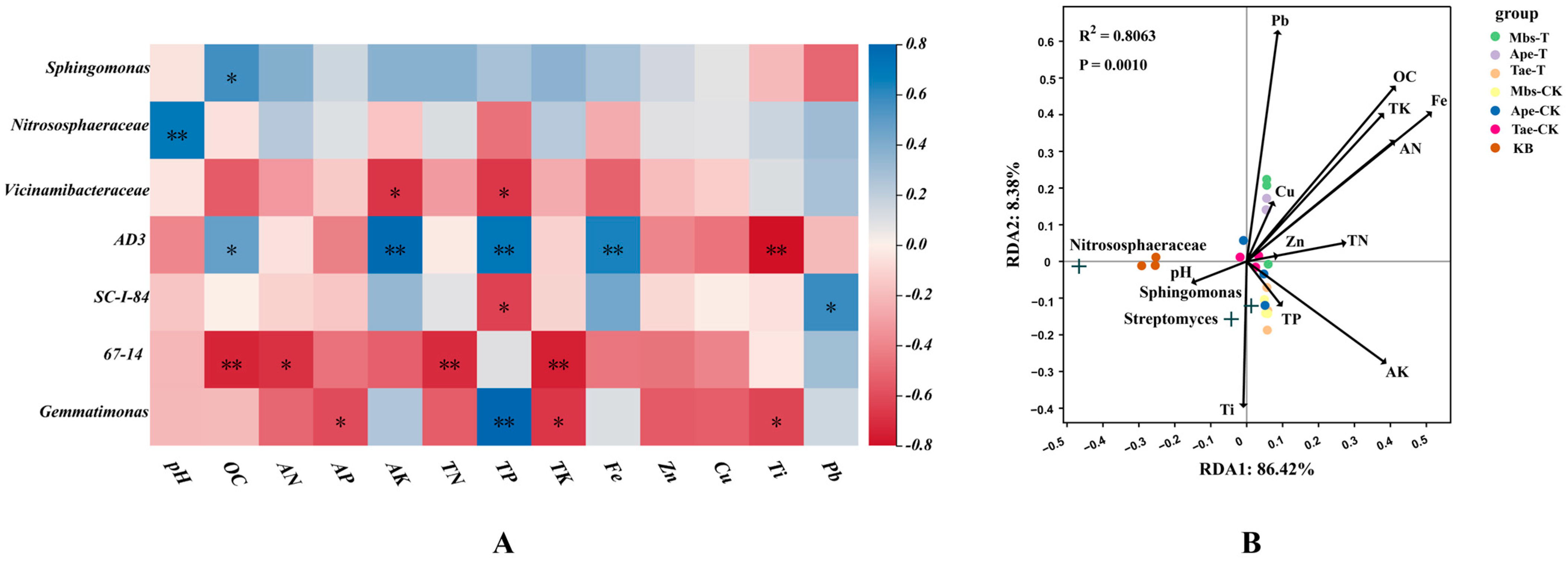

3.6. Correlation Analysis of Bacterial Communities in the Rhizosphere Soil of Three Plant Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Mining Activities on Surrounding Soil

4.2. Effects of Mining Activities on the Composition of Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities

4.3. Effects of Mining Activities on the Diversity and Functional Differentiation of Crop Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Xiang, P.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, C. Effects of Uranium Mining on Soil Bacterial Communities and Functions in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chemosphere 2024, 347, 140715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Wu, B.; Zheng, Q.; Long, Y.; Jiang, J.; Hu, X. Long-Abandoned Mining Environments Reshape Soil Microbial Co-Occurrence Patterns, Community Assembly, and Biogeochemistry. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 213, 106254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, C.; Koyama, A.; Antunes, P.M.; Dunfield, K.; Flory, S.L. Plant Communities Mediate the Interactive Effects of Invasion and Drought on Soil Microbial Communities. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1396–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, X.; Hou, L.; He, J.; Sha, A.; Zou, L.; Peng, L.; Li, Q. Effects of Uranium Mining on the Rhizospheric Bacterial Communities of Three Local Plants on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 49141–49155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyen, Z.M.; Villagrasa, E.; Maldonado, J.; Diestra, E.; Esteve, I.; Solé, A. Biosorption of Lead and Copper by Heavy-Metal Tolerant Micrococcus luteus DE2008. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 126, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, K.A.; Saadoun, I.; Kumar, K.; Helmy, M.; Dhankher, O.P. Potential Biotechnological Strategies for the Cleanup of Heavy Metals and Metalloids. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.; Peng, Y.; Yan, X. Sustainable Bioleaching of Heavy Metals from Coal Tailings Using Bacillus inaquosorum B.4: Mechanistic Insights and Environmental Implications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sánchez, A.; Tapia, J.C.J.; Lapidus, G.T. Evaluation of Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) from Tailings and Their Valorization by Copper Recovery. Miner. Eng. 2023, 191, 107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashaghian, H.; Zhang, L. Accelerated Carbonation of Mine Tailings for Acid Mine Drainage Treatment and Carbon Dioxide Sequestration. In Proceedings of the Geo-EnvironMeet 2025, held in Louisville, KY, USA, 2–5 March 2025; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2025; pp. 226–232. [Google Scholar]

- Podgórska, M.; Jóźwiak, M. Heavy Metals Contamination of Post-Mining Mounds of Former Iron-Ore Mining Activity. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 4645–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Robert, C.A.M.; Cadot, S.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M.; Li, B.; Manzo, D.; Chervet, N.; Steinger, T.; van Der Heijden, M.G.A.; et al. Root Exudate Metabolites Drive Plant-Soil Feedbacks on Growth and Defense by Shaping the Rhizosphere Microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, M.; Ma, L.; Adams, J.M.; Shi, Y. Insights into Plant–Microbe Interactions in the Rhizosphere to Promote Sustainable Agriculture in the New Crops Era. New Crops 2024, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.L.; Abbott, M.B.; Yu, J.; Bain, D.J.; Chiou-Peng, T. Environmental Legacy of Copper Metallurgy and Mongol Silver Smelting Recorded in Yunnan Lake Sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3349–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.P. Severe Contamination of Carcinogenic Heavy Metals and Metalloid in Agroecosystems and Their Associated Health Risk Assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 301, 118953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Bi, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Qin, J.; Chen, J.; Ruan, Z.; Chen, G.; Qiu, R. Source-Specific Soil Heavy Metal Risk Assessment in Arsenic Waste Mine Site of Yunnan: Integrating Environmental and Biological Factors. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 486, 136902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bárcenas-Moreno, G.; Jiménez-Compán, E.; San Emeterio, L.M.; Jiménez-Morillo, N.T.; González-Pérez, J.A. Soil pH and Soluble Organic Matter Shifts Exerted by Heating Affect Microbial Response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Fei, L.; Tuo, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, R.; Wang, Q.; Liu, N.; Fan, Q. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Regulation on Soil Physicochemical Properties, Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure of Panax notoginseng. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 326, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, P.; He, Y.; Mu, Y.; Lv, X.; Zhuang, L. Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure in the Rhizosphere of Four Ferula Species. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.J.; Edwards, M.; Riby, P.G.; Coe, G. The Use of Microwaves in the Acceleration of Digestion and Colour Development in the Determination of Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen in Soil. Analyst 1999, 124, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, T.; Lv, G.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, D. Mechanisms Underlying the Succession of Plant Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure and Function in an Alpine Open-Pit Coal Mining Disturbance Zone. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; He, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shi, S.; Fan, M.; Gu, S.; Li, G.; Tianli, W.; Wang, J.; et al. Differences in Soil Physicochemical Properties and Rhizosphere Microbial Communities of Flue-Cured Tobacco at Different Transplantation Stages and Locations. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1141720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Nguyen, V.; Littlefield, S. Comparison of Methods for Determination of Nitrogen Levels in Soil, Plant and Body Tissues, and Water. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1996, 27, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Xie, B.; Wang, J.; He, W.; Wang, X.; Wei, G. County-Scale Spatial Distribution of Soil Enzyme Activities and Enzyme Activity Indices in Agricultural Land: Implications for Soil Quality Assessment. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 535768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Q.; Bao, Z.; Tu, W.; Li, L.; Zhao, C. The Effect of Phosphate Mining Activities on Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities of Surrounding egetables and Crops. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast Length Adjustment of Short Reads to Improve Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME Allows Analysis of High-Throughput Community Sequencing Data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S.P. Exact Sequence Variants Should Replace Operational Taxonomic Units in Marker-Gene Data Analysis. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2639–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrana, J.M.; Watanabe, K. Sediment-Associated Microbial Community Profiling: Sample Pre-Processing through Sequential Membrane Filtration for 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Chen, X.; He, J.; Sha, A.; Ren, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, Q. The Impact of Kaolin Mining Activities on Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure in the Rhizosphere Soil of Three Local Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1424687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, K.; Liu, W.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; He, P.; Xie, Y. Distribution Patterns of Herbaceous Rhizosphere Bacterial and Fungal Diversities and Their Influencing Factors along the Elevational Gradient in Mountain Ecosystems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2026, 217, 106573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xie, F.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, K.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Q. Analysis of Bacterial Community Functional Diversity in Late-Stage Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Ponds Using Biolog EcoPlates and PICRUSt2. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, L.; Xiong, C.; Whalley, W.R.; Miller, A.J.; Rengel, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shen, J. Understanding Plant–Soil Interactions Underpins Enhanced Sustainability of Crop Production. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Rui, Y.; Zhang, F.; Rengel, Z.; Shen, J. Localized Application of Phosphorus and Ammonium Improves Growth of Maize Seedlings by Stimulating Root Proliferation and Rhizosphere Acidification. Field Crops Res. 2010, 119, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haichar, F.E.Z.; Santaella, C.; Heulin, T.; Achouak, W. Root Exudates Mediated Interactions Belowground. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Luo, M.; Liu, Y.; Bai, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhai, Z.; Huang, J. Rhizosphere Effect and Its Associated Soil-Microbe Interactions Drive Iron Fraction Dynamics in Tidal Wetland Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 144056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cai, Q.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, J. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Grains Uptake of Lead (Pb), Transfer Factors and Prediction Models for Various Types of Soils from China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorouri, B.; Rodriguez, C.I.; Gaut, B.S.; Allison, S.D. Variation in Sphingomonas Traits across Habitats and Phylogenetic Clades. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1146165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pombubpa, N.; Lakmuang, C.; Tiwong, P.; Kanchanabanca, C. Streptomyces Diversity Maps Reveal Distinct High-Specificity Biogeographical and Environmental Patterns Compared to the Overall Bacterial Diversity. Life 2023, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Peng, J.; Liu, P.; Bei, Q.; Rensing, C.; Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Liesack, W.; Zhang, F.; Cui, Z. Metagenomic Insights into Nitrogen and Phosphorus Cycling at the Soil Aggregate Scale Driven by Organic Material Amendments. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.L.; Waqas, M.; Asaf, S.; Kamran, M.; Shahzad, R.; Bilal, S.; Khan, M.A.; Kang, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-H.; Yun, B.-W.; et al. Plant Growth-Promoting Endophyte Sphingomonas sp. LK11 Alleviates Salinity Stress in Solanum pimpinellifolium. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 133, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xue, Q.; Ma, Y.; Chen, L.; Tan, X. Streptomyces pactum May Control Phelipanche aegyptiaca in Tomato. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 146, 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.K.; Madaan, S.; Archana, G. Antibiotic Producing Endophytic Streptomyces spp. Colonize above-Ground Plant Parts and Promote Shoot Growth in Multiple Healthy and Pathogen-Challenged Cereal Crops. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 215, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Guo, D.; Li, Y.; Shaheen, S.M.; Wahid, F.; Antoniadis, V.; Abdelrahman, H.; Al-Solaimani, S.G.; Li, R.; Tsang, D.C.W.; et al. Streptomyces pactum Addition to Contaminated Mining Soils Improved Soil Quality and Enhanced Metals Phytoextraction by Wheat in a Green Remediation Trial. Chemosphere 2021, 273, 129692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; Haferburg, G.; Schmidt, A.; Lischke, U.; Merten, D.; Ghergel, F.; Büchel, G.; Kothe, E. Heavy Metal Resistance to the Extreme: Streptomyces Strains from a Former Uranium Mining Area. Geochemistry 2009, 69 (Suppl. 2), 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.; Goux, X.; Echevarria, G.; Calusinska, M.; Morel, J.L.; Benizri, E. Community Diversity and Potential Functions of Rhizosphere-Associated Bacteria of Nickel Hyperaccumulators Found in Albania. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Effects of Different Plant Root Exudates and Their Organic Acid Components on Chemotaxis, Biofilm Formation and Colonization by Beneficial Rhizosphere-Associated Bacterial Strains. Plant Soil 2014, 374, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Khan, A.L.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: From Diversity and Genomics to Functional Role in Environmental Remediation and Plant Growth. Cri. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Sui, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y. Response of Surface Soil Microbial Communities to Heavy Metals and Soil Properties for Five Different Land-Use Types of Yellow River Delta. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Kaur, M.; Thompson, L.K.; Cox, G. A Historical Perspective on the Multifunctional Outer Membrane Channel Protein TolC in Escherichia coli. Npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lan, W.; Yang, F.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Xiao, Y. Invasive Amaranthus spp. for Heavy Metal Phytoremediation: Investigations of Cadmium and Lead Accumulation and Soil Microbial Community in Three Zinc Mining Areas. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 285, 117040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Liu, C.; Tian, X.; Kim, Y.R. Functions and Regulation of the Outer Membrane Protein TolC in Vibrio Species. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delepelaire, P. Bacterial ABC Transporters of Iron Containing Compounds. Res. Microbiol. 2019, 170, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.; Law, A.D.; Sahib, M.R.; Pervaiz, Z.H.; Zhang, Q. Impact of Root System Architecture on Rhizosphere and Root Microbiome. Rhizosphere 2018, 6, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurav, K.; Kannabiran, K. Biosorption of Cd(II) and Pb(II) Ions by Aqueous Solutions of Novel Alkalophillic Streptomyces VITSVK5 spp. Biomass. J. Ocean Univ. China 2011, 10, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, S.D.; Chater, K.F.; Cerdeño-Tárraga, A.-M.; Challis, G.L.; Thomson, N.R.; James, K.D.; Harris, D.E.; Quail, M.A.; Kieser, H.; Harper, D.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of the Model Actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 2002, 417, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Häggblom, M.M.; Li, M.; Guo, L.; Li, B.; Kolton, M.; Cao, Z.; Soleimani, M.; Chen, Z.; et al. Characterization of Diazotrophic Root Endophytes in Chinese Silvergrass (Miscanthus sinensis). Microbiome 2022, 10, 186, Erratum in Microbiome 2022, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Qiu, B. Phytochelatin Synthesis Plays a Similar Role in Shoots of the Cadmium Hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii as in Non-resistant Plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Mbs-T | Mbs-CK | Tae-T | Tae-CK | Ape-T | Ape-CK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN (mg/kg) | 394.19 ± 2.09 d | 172.53 ± 1.94 f | 353.64 ± 1.67 e | 439.99 ± 3.47 c | 553.13 ± 3.42 b | 746.04 ± 2.13 a |

| AP (mg/kg) | 14.37 ± 0.79 e | 21.71 ± 1.32 c | 70.74 ± 0.87 a | 18.10 ± 0.99 d | 28.48 ± 0.20 b | 18.60 ± 0.66 d |

| AK (mg/kg) | 387.60 ± 3.88 d | 331.10 ± 3.04 e | 588.52 ± 4.56 b | 526.59 ± 4.44 c | 336.60 ± 3.29 e | 838.69 ± 8.34 a |

| TN (g/kg) | 2.39 ± 0.01 e | 1.13 ± 0.01 f | 3.14 ± 0.01 d | 3.52 ± 0.04 b | 3.25 ± 0.02 c | 5.67 ± 0.01 a |

| TP (g/kg) | 0.91 ± 0.01 d | 0.77 ± 0.04 e | 1.13 ± 0.01 c | 1.63 ± 0.03 b | 0.94 ± 0.01 d | 4.94 ± 0.03 a |

| TK (g/kg) | 20.20 ± 0.15 c | 5.94 ± 0.18 f | 23.08 ± 0.21 a | 14.77 ± 0.17 d | 20.81 ± 0.18 b | 9.79 ± 0.16 e |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Ren, H.; Zou, Z.; Shen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, M.; Li, Q. Mining Activities in Iron Ore Areas Have Altered the Diversity and Functional Structure of Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities in Three Crops. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2728. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122728

Xu Y, Ren H, Zou Z, Shen G, Zhang Y, Tan M, Li Q. Mining Activities in Iron Ore Areas Have Altered the Diversity and Functional Structure of Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities in Three Crops. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2728. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122728

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yanping, Hao Ren, Ziping Zou, Guohua Shen, Yunfeng Zhang, Maling Tan, and Qiang Li. 2025. "Mining Activities in Iron Ore Areas Have Altered the Diversity and Functional Structure of Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities in Three Crops" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2728. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122728

APA StyleXu, Y., Ren, H., Zou, Z., Shen, G., Zhang, Y., Tan, M., & Li, Q. (2025). Mining Activities in Iron Ore Areas Have Altered the Diversity and Functional Structure of Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities in Three Crops. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2728. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122728